1740 to 1780

See “Stays & Corsets Introduction Overview “, and “History of Corsets 1780-1880” for continuation

Secret to the 18th c. Silhouette – Stays

In 1745, the word “stays” was plural, but stays were, and are, really one very important garment. The predecessor to “corsets” that would come in 1800, they are part of a linear history that ends up in modern times with bras and panties, where women had to wear SOMETHING underneath their clothes in climates other than the tropics.

We are discussing non-indigenous women from Europe and North America, so we can cut straight to the history of stays and corsets, passing by those who wore nothing underneath or nothing on the outside.

Before the 18th century, stays were called “A Pair of Bodies”. They were forged of metal wire, or made of leather. These “bodies” through 16th and 17th century Europe and North America were usually worn on the outside as the main garment or bodice (“bodies”, “bodice”? Recognize the latin roots?).

It was in about 1720 that “bodies” started to be worn as an undergarment. Part of the reason was the techniques improved and availability of materials and fabrics changed, but largely it was cultural; e.g. the leaders of fashion had changed, and so what was fashionable changed under their direction. The silhouette became more gracefull and longer to accommodate the whims of the French Court, and England followed the French, so of course the early English based Colonists in the “New World” that would become America, followed the English.

Note there were no sewing machines; even the rudimentary concepts of the early leather and wool working machines wouldn’t come to light for another 120 years, so each and every stitch of every item of clothing was made by hand. After the 1850’s, and especially after the lightweight Singer machines were introduced worldwide at a price most women could afford in about 1861, most (by then called “corsets”) stays/corsets would be made by machine.

Metal eyelets were invented for practical use in garments in the 1830’s, so before that, all eyelets, closures, lacings, and everything about an undergarment was made by hand.

By men’s hands, we mean. Picture metal, leather, and thick fabrics that were used in the early 18th century (1700’s) “bodies”. Add to that the cultural “taboo” against women being tailors, and the deep history of tailor’s guilds which were all men, and you can understand why the “body” was a man’s world. (Which by the way, makes for some interesting movies and novels regarding tailors and their extra-marital exploits such as Don Juan, the fictional “libertine and Seducer of Seville” later put into the opera “Don Giovanni” in 1787 London, or the stories of real seducer Casanova and his exploits in Italy and Paris in the 1750’s).

By the 1740’s, the “bodies”, now called “stays, were essential to every woman’s wardrobe. ALL women of every class, age, size, and shape wore them in some form. Poor and middle classes had readymade or hand-me-downs from their wealthy employers or benefactors. Upper classes had custom fit.

Stays were necessary because they covered the breasts, protected the abdomen, and supported the back. Even children wore stays; boys AND girls until a certain point in childhood decided by parents (when a boy would “breech” meaning leave his long pants and the equivalent of a thundervest to wear a man’s short pants). Typically children’s were made of leather, since it was the cheapest fabric available.

One must remember class and social status dictated fashion in the 18th century, so everyone had something. It was a matter of the quality, cut, fit, and design that made the difference. Even charity children were issued stays by wealthy benefactors.

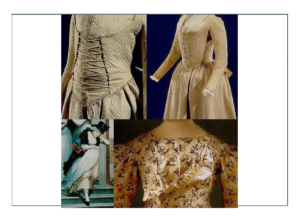

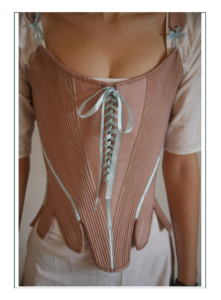

The point was to give support and protection, and to create the fashionable silhouette. STAYS WERE NEVER MEANT TO MAKE A TINY WAIST OR TO SHAPE THE BODY. They were so stiff, and so structured, that they could stand on their own without a body in them. It was much like wearing a saddle or barrel around you.

The other important job stays had was to make a smooth surface without anything that could catch or cause a tear or damage to the outer garments. They were to be the underlayment for a fashionable cone that would trick the eye into seeing that shape no matter what the shape of the wearer really was.

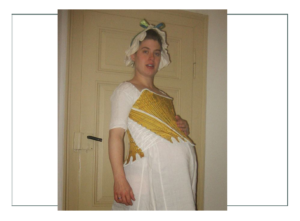

There were specialty stays throughout history, and with a garment of such heavy and stiff material such as the early stays, the greatest challenges must have been to accommodate pregnancy and nursing. Since the typical woman had up to 13 babies in her lifetime (in 1765, 9-11 of those children would survive infancy in the American Colonies which was very good for the time, although women’s life expectancy was only 56 and we can guess it had to do with having babies every year of their adult lives), these would be needed.

There are few extant examples from this era of modifications for pregnancy, and a few as shown here of nursing. they would cut little “doors” out of the stays over the breasts for nursing. Pregnancy was accommodated at first by loosening the lacing, and later by wearing the stays up high or wearing shorter stays that could rest ABOVE the growing belly.

Low class women had loose lacing and a comfortable fit. High society did some tight lacing to achieve the fit. (We can only presume that might be because lower class were lean from hard work and a different diet than high class who had more leisure and more variety in food choices, although there is no research showing that wealthy women of the time were fatter than poor; in fact, extant garments indicate everyone was very lean and smaller than today’s women in stature overall, and that the obese or extremely large woman was somewhat a rarity).

Well fitted stays were somewhat comfortable and gave light support as one would wrap a tape around their body to give back support today. They did not pinch, and a good fit would have a 2-5″ gap in the back between the edges after lacing.

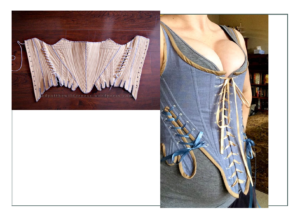

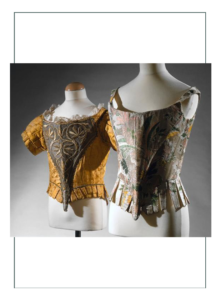

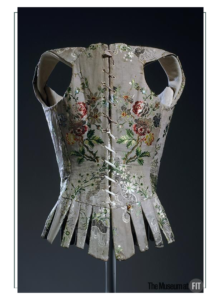

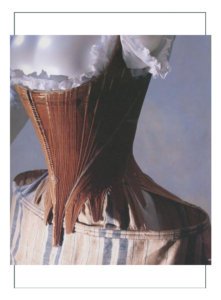

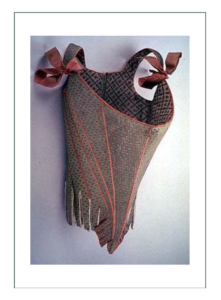

Structure in addition to the stiff and heavy fabrics, was added in specific directions and places to each individual “bodies”. Typically these were vertical or diagonal on the body, made in narrow channels. The most dominant was “baleen”, the cartilege from a whale’s mouth. 2nd was wood or reeding – sometimes hard wood carved and then slipped into narrow channels, and sometimes a naturally thin strip of wood such as bamboo that was inserted. Baleen was most popular until the next century where whales almost became extinct due to hunting them for corsetry. Today’s reproduction stays use various plastics, wood, reeding, and metal, or a combination of those.

The term “half-boned” means some areas do not have the channels and strips of stiffener inside, but only on key points. The term “fully boned” means every inch of the surface is covered with channels and stuffed with a stiffener.

In the 1730’s and 1740’s, women began to wear straps on their stays, although many still did not. Most of the “bodies” prior to that did not have straps (although some did).

In the middle of the century (1740’s-70’s), shoulder straps became optional. It was at the end of the century (1780’s and ’90’s) when the waistlines of fashion rose, so did the waistlines of stays rise, and straps rose to great popularity, although many women still chose not to have them and that was socially acceptable. It was in the 1780’s that horizontal boning became more prevalent, although most still did not have it. The horizontal bones supported the breasts with the lower necklines of the later eras, so the breasts could be worn nearly full outside the garment without spilling over. All of the earlier stays lifted the breasts to be visible, but also somewhat flattened them as necessary to create the inverted cone shape desired for fashion.

DETAILS BY THE DATE

Fabrics, colors, details

(Note – there is no distinct line. Styles and designs crossed over and blended and merged. These are the common characteristics)

1710-1720

- Shape flat with a little curve at the bust (later ones were rounded all around)

- Rigid frame

- Looong and low center front point

- Only a few laced in front AND back. Most laced on in the back

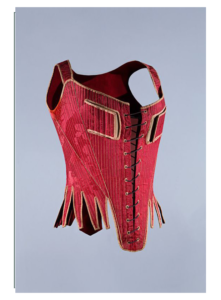

- Outer fabrics were rich in color

- Silk brocade for the wealthy

- Cotton and Linen for middle and low classes

- Most available, cheapest, and easy to get was leather, so almost all low class women wore leather

1720-1730’s

- Still a long and rigid look with central point and mostly back lacing same as last decade

- Heavy & crisp silks

- White, pale blue, pink, bright yellow

- Damask & brocades, especially for straps

- Leather and Linen still predominant for mid and lower classes

- Shape was flat and flattened breasts while still lifting them

1730’s & 1740’s

- Optional shoulder straps added. These always tied in front and were integrated into the body in the back

- Waist tabs were added AFTER the main body was completed (later periods added them integrated from the start)

- Front lacing with a stomacher in addition to back lacing was increasing in popularity

- Almost always fully boned

- By the 1740’s eyelets were added to the bottom to tie “hips” (pads on the hips) to

- Eyelets on the bottom remained an option through the 1740’s

- The shape was still conical, although it was getting less flat and more round

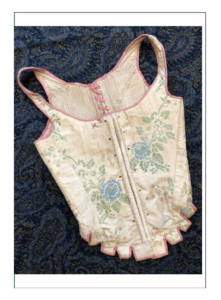

1750-1780

- Green became very popular; especially used together with pink mostly in the 1750’s and 1760’s

- Cotton was cheaper and more available, so more women of all classes started to wear cotton, although linen was still the cheapest and most popular with women of middle and low classes

- Silks were very thin, and brocades were thin too.

- The conical shape was still the style, but it softened a bit

- Horizontal boning was added to the bust, especially later

- Towards the 1780’s white cotton or white linen became very popular

- Wooden Busks were added, and the shape got even rounder yet with the breasts separated and the goal to have two distinct round orbs rather than the flat on the bottom yet raised and full breast on top

1770’s Distinctions

There were drastic changes to the shape and length of stays through this, a transitional time

- The bum roll to widen sides and back replaced the side-only paniers in Court dress and high fashion

- 1770-90’s were the most extreme in a somewhat symmetrical cone shape around the whole body

- They could be front lacing or back lacing

- They could have a stomacher or not have a stomacher

- They could have straps of many types or not have straps

- The bottoms were wider, not the pointy center fronts of the 1720’s

- Full or half-boned were fine

- Slowly they got shorter as waistlines turned to the Regency under the bust styles that would dominate starting in 1793 and through the early 1800’s

- Waist tabs were integrated into the pattern from the start

Interesting 1775 approx. design details:

FABRICS

Cotton:

Cotton was used even when it was outlawed. It got cheaper as the century progressed, but was still more expensive than linen. As time went on, there were more and more prints and colors available worldwide, and of course the more colors and fancy the print was, the more costly the fabric.

Stays being an undergarment were almost always of the less expensive solid colors if they were cotton (or linen or wool). Only fancy prints and blends like cotton and silk were used by upper classes and wealthy women.

Cotton Duck:

This is a very thick woven cotton which protects boning. Natural or white is used for the inter layers of stays and is not seen.

Linen:

Linen was popular in all geographic locations because it kept one cool in the heat and warm in the cold. For centuries it was a favorite, grown from flax which grew in most places. The fabric’s secret is that it whisks away sweat, cooling or warming the body.

Historically linen was the most inexpensive and easy to get of all fabrics. It could be manufactured and spun at home or in undeveloped Colonies. It could be grown by an individual. Most typically in the American Colonies and in the mid-century (1770’s approx.) a woman might grow and spin the flax and then take it to a weaver in a nearby town or village. Those nearer to population centers would just buy the finished fabric directly from the textile mill, or a shop in town.

Linens must be PLAIN SOLID COLORS to be historically accurate.

Wool:

In the 18th century, the term “stuff” meant worsted wool. Wool is durable, flame resistant, and one of the oldest fibers on earth used for clothing. Most of the extant garments still intact today are of worsted wool or linen.

Pink, green, brown, white, or blue worsted are recommended for all 1770’s depictions for all class depictions by historians who have studied the statistics of use based on extant garments.

Silks:

Silks were woven in different ways using different techniques and types of other threads to yield artful forms such as those coming out of India in the 18th century. Jacquard is a special weave made by an attachment to a textile weaving loom. It is a technique added to and used on a brocade design which makes a raised or woven design that is still integrated. Jacquard is the name of a man who invented a punch card much like the first computers in the mid-18th century.

Brocade was largely used for stays by the upper classes. It is a lavishly decorated shuttle woven fabric that might be made of silk, cotton, or other, but most historic examples are silk. Today silk is often blended with rayon or polyester. Historically and today, most brocades you find have gold or metallic threads on warp or weft of the weave. The origins of brocade are also in India. A Jacquard technique might be added to a brocade, making a raised design like you see on today’s fine draperies.

Scenes and patterns like women and men cavorting in a landscape are woven into brocades. They look like they have been embroidered by hand. Most commonly brocades have floral patterns.

Damask is similar to brocade, but has more geometric shapes and florals. They also have scenes of domestic life. They might be woven of silk, wool, linen, cotton, or synthetics today. Most are of some percent silk. Damask is different than brocade in that the pattern is reversible and more subtle effects like shading are possible such as light and shade because of the shorter weft patterns. Double damask is highly priced.

HISTORIC COLORS TO CHOOSE FROM

Black: upper class & clergy except black wool which was very common for the lowest classes

Blue: from Indigo dye only! (not the bright blue we know today, but the blue/green/teal color of indigo.. think Union Army in the Civil War). Even this was very pricey and so only worn by the upper classes

Brown: All types of browns were readily available, cheap, and worn by ALL!

Green: was costly and very popular. It was special, so mid and upper classes wore it for daily wear, whereas lower classes could not afford it

Gray: very, very widely used by all classes

Pink: like green it was VERY popular with the mid and upper classes, especially used with green. It was less costly and more accessible than green, and so sometimes found among the lower classes

Purple: just NO. The blue and purple range were simply not done except for royalty

Red: very RARE and very very costly. Upper classes and royalty wore it. There were some orange/reds and pink/magentas from natural dye sources available to middle class, but only the paler pinks were common

Yellows: YES! Lots and lots and everyone around the word in all types of fabrics. Yellow was an easy dye from nature to make and mix with others for a wide variety of color choices.

Orange: “sometimes”, but only by middle upper and upper classes. That’s because it had to be a (common) yellow with an (uncommon) red to get get orange

White: unbleached was popular in the mid 1760’s to mid 1770’s. White on white brocades, or white silks with embroidery were popular in the 1770’s for all classes

Brown: on brown popular for all and easy to get, especially in linen or leather

NOTE: Most often regardless of the main color of the body, it was sewn in a contrasting thread. Favorite thread colors were brown, natural (unbleached flax), white, or one of the colors above according to class and availability.

Favorite thread-to-body combinations included:

- pink with green

- brown with natural

- yellow with white

- gray with white or brown

- brown with lighter or darker brown

AND…: White kid leather was common for lining the insides of the tabs, as illustrated on many extant garments of high and low classes.

NOTE ON HOW WE KNOW WHAT WE KNOW ABOUT COLORS & FABRICS

Most of today’s knowledge about the history of garments comes from studying real ones in museums or by collectors. In the 19th and 20th centuries this is easy, because real garments can be explained by use of photographs and reproduced documents.

This is not so easy in the 18th century because not only has another 100 years aged the examples, but the only recordings are by portraits and limited texts. There were no fashion magazines, and information traveled around the world by the written word, so that was limited in colored pictures of what women wore. Napoleon in 1804 shipped dolls wearing fashion to show rich women what the current fashion was, so that is some help starting in the 19th century, but mostly for the Georgian/Colonial periods one has only the garments, and the portraits – and portraits were rarely of the common man, although there were notable painters at the end of the century painting every day people.

Many upper class extant stays that have survived and are on display seem to be indigo blue with natural or white contrast. It is perhaps because this color of dye has survived. We know many of the naturally dyed pinks, oranges, and reds made in America have faded to tan or beige due to incorrect use of mordants or other chemical issues.

There are also many examples of red/oranges; again upper class in the museums. One has to consider if this might be because upper classes took very good care of their best clothing because they paid for it (as opposed to most of the populace getting hand me downs from the upper classes), and so they were stored well for generations and passed along.

The other theory is that there are low class garments hidden away in museum back rooms in the many more common fabrics and color combinations, but that curators don’t put them on display regularly since the public is more interested in the ornamented stays, and not the boring old brown leather ones or plain white.

Recommended Fabrics for modern depictions:

Outer: 1. Linen, 2. Wool, 3. Cotton, 4. Silk

Inter: 1. Cotton duck, 2. Linen

Backing (lining or 2nd inter): 1. Linen, 2. Wool, 3. Cotton

Click to return to Susan Hurlbutt Project

Click here to go to the History of Corsets 1780-1880