1770, Mary Katharine Goddard

Publisher/Printer/Postmaster

Multiple Gals’ Depiction

Woman Who Signed the Declaration of Independence

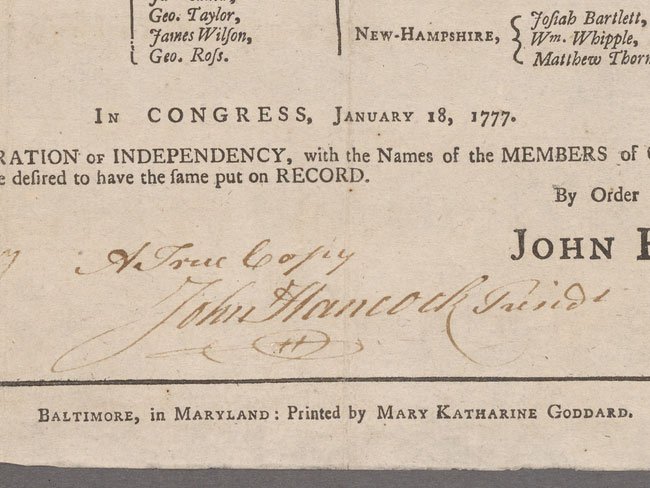

At the bottom of the United States of America’s Declaration of Independence, after the signatures of the Founding Fathers after John Hancock, there is a printed advertisement of sorts. Mary Katharine Goddard published on the first copies to be distributed, her name and location. In essence, she was the only woman to sign that document.

The Smithsonian Magazine says Mary K was “Likely the United States’ first woman employee, this newspaper publisher was a key figure in promoting the ideas that fomented the Revolution”

In that article dated November, 2018, Goddard is credited with publishing the first copies of the document so that it could be distributed to enhance the cause.

Goddard had been watching her brother become more involved in the Colonists battle against the British for three years. She took over the 6 month old “Maryland Journal” newspaper from her brother who had run it into indebtedness and was sent to debtor’s prison. In her patriotic articles, she lambasted the British for specific actions against the Colonies. Over the next 23 years of her publishing career, she would continue to support the cause of American democracy.

Described by her biographer in 1862, Mary was known as ““dependable and… brilliantly erratic,” Ward L. Miner wrote in William Goddard, Newspaperman. Her father was the Baltimore Postmaster, but he became seriously ill and sent Goddard’s little brother to apprentice. With Mary and the brother taking care of the publishing business, it freed up the father to concentrate on building his lasting dream, a United States Postal service outside of the control of the British.

First Woman Postmaster Too

According to the Smithsonian, that July, the Continental Congress adopted Mary’s father William Goddard’s postal system for the country, then promptly appointed Benjamin Franklin as postmaster general of the nation. Mary Katharine was named Baltimore’s postmaster that October, which likely made her the United States’ only female employee at the time the nation was born in July 1776. When Congress turned to her to print copies of the Declaration the following year, she recognized her role in a historical moment. Though she usually signed her newspaper “M.K. Goddard,” she printed her full name on that document.

(for more indepth history, see the Mary K Goddard Historical Context Page here which includes links and images)

The depiction of Mary Katharine is a Buffalo Gals’ project, for use n educational programs focused on both the Colonial Period and Working Women (“what women were doing” shows). She will be played by 3 different models, and therefore her ensemble is flexible as were all garments in the middle 18th century, as well as in purpose. She will therefore have mix and match pieces that cover the different roles and occupations in her life.

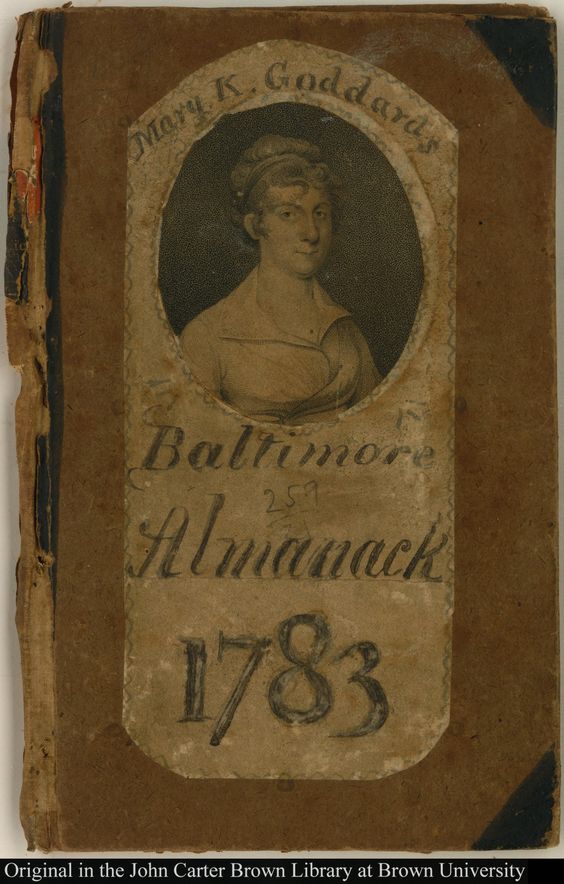

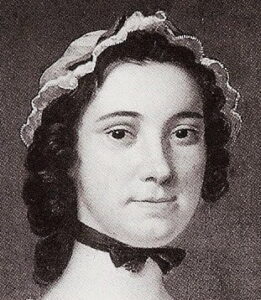

We note several of the portraits of her are in the Regency style, or about 1800, included the book cover above dated 1783. While it would be consistent that she should be in the peak of her Postmaster career around 1800, her history is most often centered around 1775-1778 and her role in the Revolutionary War.

We have therefore chose n to start at 1770 in her early adult professional life as a printer, and to stay within that earlier decade. Regardless of the era and which portrait you study, it is clear she wore fashion for work. This we will discuss in the Design Development and Fashion History Pages here. More resources regarding fashion and lifestyle, particularly diving deeply into colors, fabrics, undergarments, and geographic differences can be found on the specialty pages in the Colonial Section on this website.

From the inspiration and research of our other Colonial projects, the design determination for this project will be done largely out of our heads., as we can best assume this was an extremely intelligent, hard working, driven woman who ignored many of the norms of the day. Our ensemble will be unique in that it will be geared for the working woman in a man’s workplace, while maintaining the proper decorum a woman of that day would have needed to be accepted in that man’s world (e.g. could not dress like a man as some did in particularly the 1860’s and 1880’s if she was to be heard by men or they would dismiss her as too radical).

From what we can tell of this woman, she was well accepted and respected by men of power, and more importantly, TRUSTED to get their ideas out to the people and to implement programs such as the postal system that would benefit the every day people as well.

Click here to go to Historical Context Page (next) or scroll down to see the finished project

Click here to go to the Design Development Page

Click here to go to the Fashion History Page

In order of wearing

Note the early(1760-1770) shape of the raised center back or Watteau silhouette with full fabric pleats. In the next decade+ the back would typically drop to the waist and be fitted, with a tapered or pointed center back peplum or full pleated skirt. Part of this was due to the switch from the desired Court silhouette using paniers and side fullness to the rump fullness.

Crossover of styles and silhouettes in the mid-18th Century are not precise as clothing was valuable and women did not just abandon something to grab the next style except at the high Court levels. Since stays were much the same until at least the 1780’s, the silhouette was much the same. (in the 1780’s the boning and structure changed to keep the bosoms from falling out of a lower bodice, and the length was shortening as fashion headed to the short Regency styles to come).

Shift: Lightweight linen, a bit lighter than usual with 3/4 sleeves and no ruffle for simplicity. Slight tuck/gathers at sleeves

Stays: Navy blue (oh so accurate) linen with tan linen lining and linen trim. Synthetic bones full flat boned plus silk satin ribbon. Front and back lacing with shoulder straps including all eyelets hand sewn using period correct technique

Small Rump: soft small bum roll of linen with organic cotton stuffing for comfort

Inner Petticoat: quilted (it’s an old curtain!) cotton with twill tape ties, adjustable

Outer Petticoat: brown rust flax based linen dress (5.2 oz) weight. Tied back to front to back to fit over rump with quality linen tape waist band. Overlap leaves pocket slit

Linen Bodice: same linen to match outer petticoat with semi-sheer silk sleeves and cotton muslin lining. Pin closure using historic based straight pins. Can be worn under shortgown using shortgown as a jacket

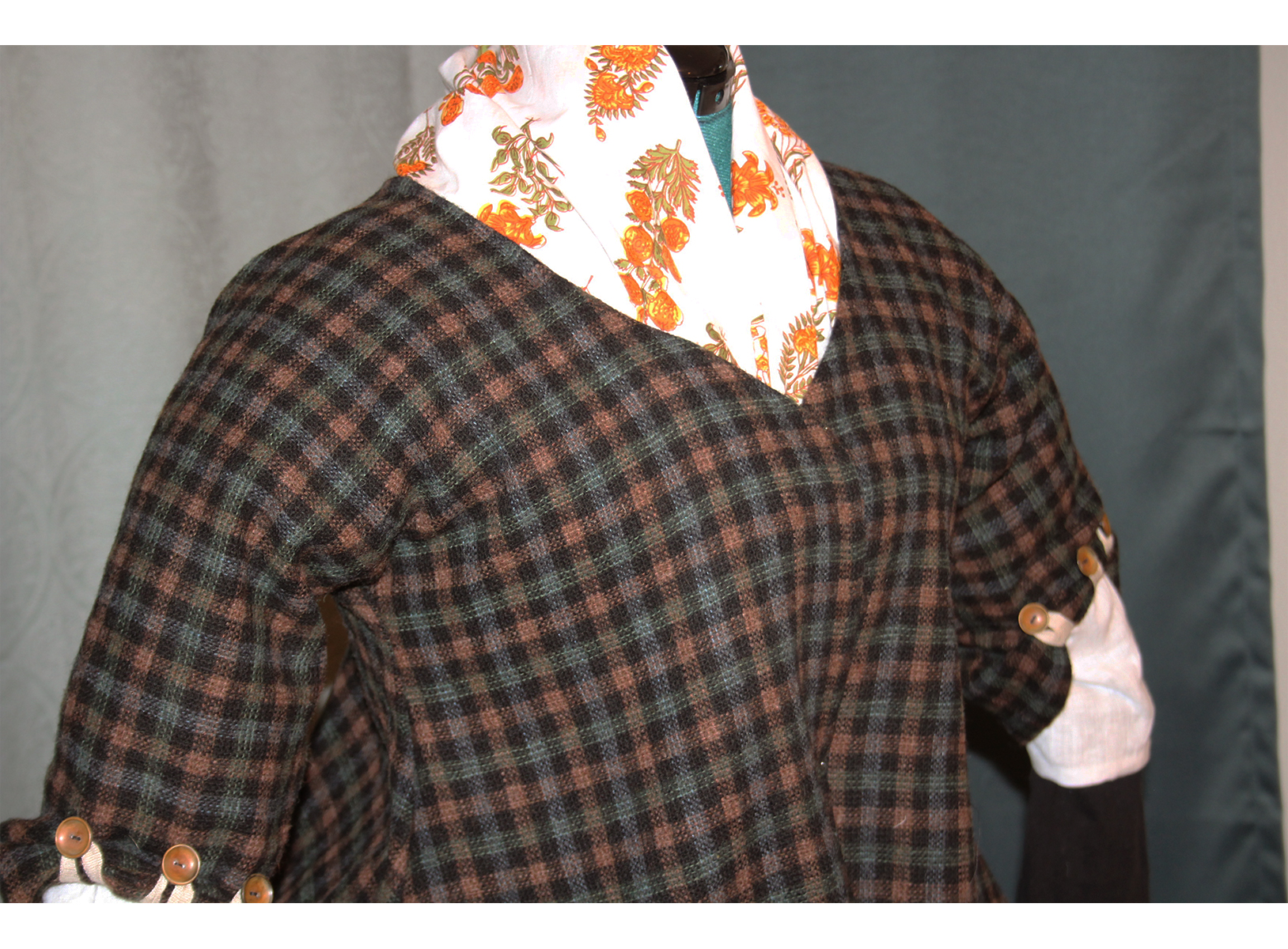

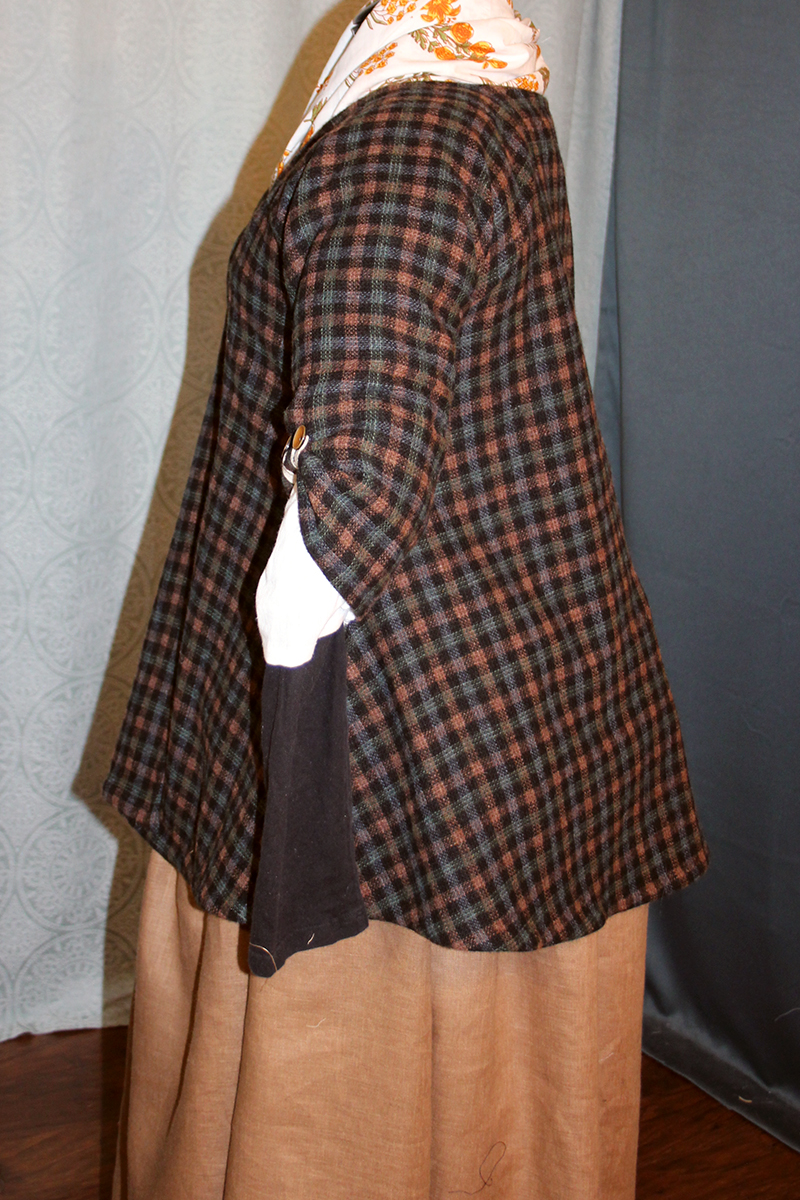

Shortgown: cotton plaid heavy woven loose fit

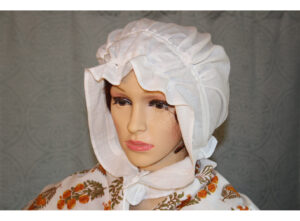

Mobcap: with lappet (over the ears) for safety in the print shop; no frills. Handkerchief linen 80:20 Cotton entirely made by hand using historically correct stitches and methods. Cotton string

Robe a l’anglaise “fancy” dress to go over same basic garments

Period shoes: replication with gold brass buckles

Stockings: 2 pairs over the knee (no garters): Hand block printed 80% silk/20% lycra over the knee and 80% cotton/20% lycra for workwear. Fancy ones will be worn with the fancy robe (gown), while cotton are coarse and will be worn with the shortgown.

Fichu: printed cotton from India sheer machine hemmed

Silk Fichu: As part of mix and match, this could be worn to “dress up” the ensemble. It is 100% silk from a reproduction source. The fichu would be tucked into the stays prior to putting the bodice on, and there were many ways to wear it which revealed more or less of the decollatage. We think while working, our historical person would have worn a plain, white linen fichu and then changed it to go out or to class up the ensemble. This we hand finished using a Colonial hemming technique.

Outer Petticoat: Ginger linen with twill tape

Vested Bodice: Ginger 5.3 oz linen (dress weight). It would be unusual for a woman to wear a sleeveless bodice, but this is an unusual woman. Working in a print shop in summer, this is the equivalent of wearing one’s “shirt sleeves”. Linen is cool, breathable, and forgiving.

This bodice is appropriately fitted to the 1760-1770 period with the higher-than-waist in back, very full and long coatlike peplum, round neck, and fitted torso. It is shown here with both the silk and cotton fichus which would be worn, or possibly a plain white linen one for wiping sweat or ink off he face and fingers. The bodice would be worn over the shift, which was appropriate to be seen in public if only the sleeves and neckline. While machine made, we’ve put some great hand detail into the building of the armholes, fichu, and handmade buttonholes. It is fully lined.

European Bedgown: Think of this as a Colonial sweatshirt. Made of the softest woven cotton checks, this would be thrown on in the morning to make breakfast or later in the day to do some chores. Shaped as per the style of the day with long peplum and jacket like shape, it is fitted through the waist and back with a high back, but the front is loose and hangs freely. It can be pinned or just used with an apron to hold it on. Sometimes a bedgown was worn over another bodice such as the linen one shown here, or sometimes just over the shift. Type of fabric and fit had a lot to do with the season and weather; this is for winter or a chilly morning.

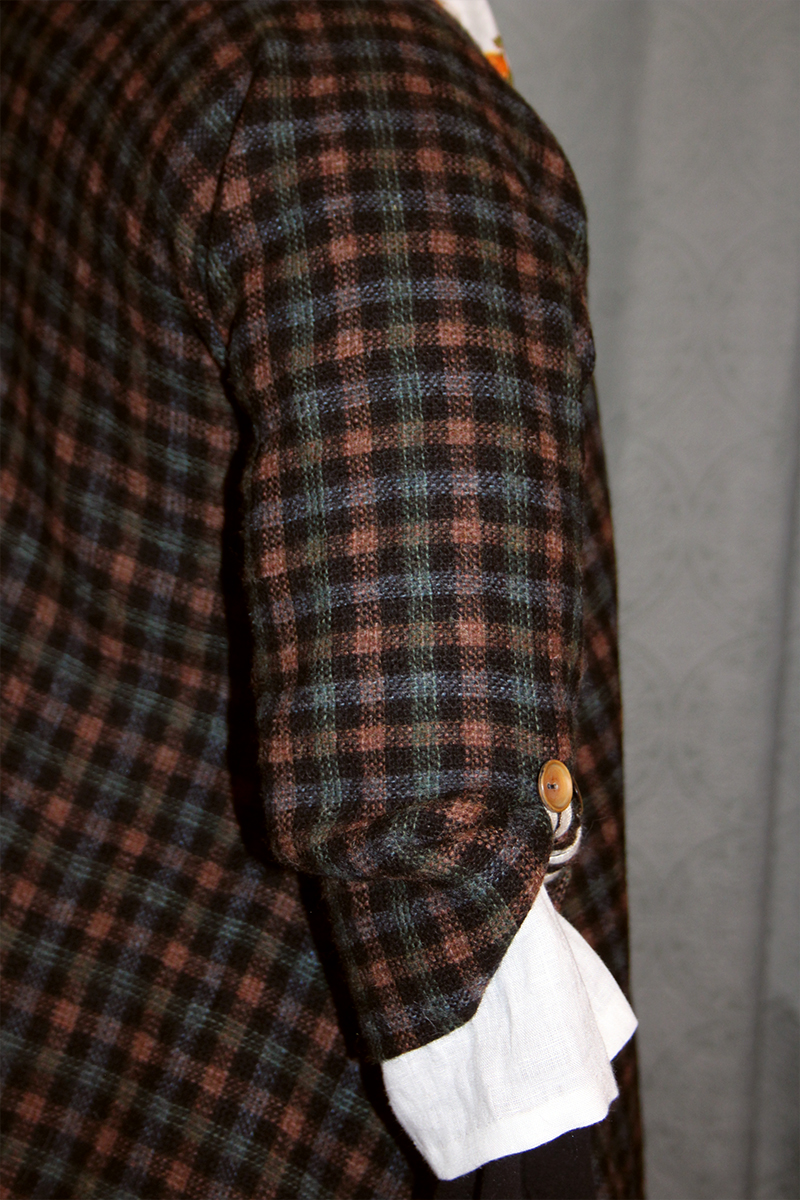

Note the very unique sleeve detail. Since Colonial sleeves were cut on the straight of the grain of the fabric (bias wouldn’t be used until the late 19th century) elbows got worn out by being stressed and could be uncomfortable. The buttons pull the sleeve up inside the elbow, while allowing fullness for the elbow to bend. They could also be unbuttoned and the sleeves could be worn down and straight or “scrunched” up above the elbow. This flexibility was necessary as this was a garment worn while working hard, as were most tasks for women of the day.

Note how this would make a great maternity garment, which it most likely was.

Apron: Worn publicly, casually, for work, or for dress up, the 100% flax-based linen apron was the all utility garment for every woman of every class. This is of ivory 5.3 dress weight with cotton twill tape. It is entirely hand made (no machine stitching) and is appropriately gathered to fit across the front and somewhat to both sides.

Since there were no pockets except those worn around the waist under the petticoats, the apron was tucked up under its waistband (also of twill tape) to make a full front pocket or just one side. We show this apron’s versatility when worn with the various layers of garments “over or under”.

Note, it is a worn out apron that is worn by menstruating women in these days that preceded sanitary products. They would wrap it between their legs and wrap the waist around their waists to hold it up; like a giant diaper. Easily washable and reusable, it was very healthful too.

Midnight Blue Kerseymere cloak: silk brocade lined for winter wear, 3/4 length and big hood trimmed in real winter rabbit. This specific color and type of 100% pressed wool and the source where we found it in the UK is EXACTLY what the Colonial military uniforms were made out of! It was very common, dyed with Indigo, and locally sourced. The Redcoats had the same fabric, only in red and from England. This one is unlined because the fabric is so heavy the lining would weight it down and drag despite any amount of featherstitching. Lining was optional back then too.

While cloaks were the only winter garment for women, they were fairly easy to make. They might have a hood, or just a collar. Lightweight fabrics like silk and fur were used with a collar for dress up, while a cloak like this with a hood and dense wool were for every day in winter. The plus side was a woman could make one of these at home. The downside was the tremendous amount of fabric (3-4 yards of 60″ width or triple that as fabric came in 22″ bolts back then) needed. Today, as then, it is the most expensive of all our projects for this character and a major investment.

An interesting sidenote… as you might guess, we are a big fan of historical fiction shows as well as historical documentaries. There are even some shows on “fixer uppers” about the Colonial era. Having completely immersed ourselves in one such show about renovating a house near Baltimore (near where our character actually lived) that was built in 1707, we watched the use of historically accurate materials, techniques, colors, and artistry.

After the show, we went to our shop to work on this, and it was.. just.. right! The colors, textures, techniques, and everything about this as it stood on our mannequin was just intuitively right. We could see it in our mind’s eye placed in that home 70 years after it had been built.

Sometimes the true test of historical accuracy is not whether there are extant garments or real examples, but a gut feeling that things are just RIGHT. This project is one such.

ALSO

We were going to keep going with our mix and match to build a “going to a party” ensemble for this woman. We decided though, to build that as a separate ensemble for our Gals of different sizes so we can show both in the same show at the same time.

It will still be linked to the Goddard project and research, but will be considered a separate project for purposes of our educational programs.

Click here to go to the (fancy) day dress Goddard “extension” project (coming soon!)

Click here to go the Historical Context Page

Click here to go to the Design Development Page

Click here to go to the Fashion History Page