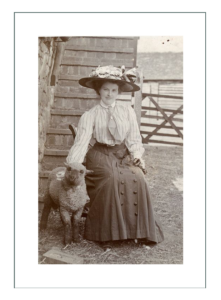

The “New Woman” was a “Working Woman”. They were out of the home and into the workplace, politics, sports, and every imaginable activity. It was the Edwardian Era, but “true Edwardians” who followed the new king hated the concept of the Working Woman. They worked very hard a avoiding work, and their fashion reflected this leisure ambition.

High Fashion designers saw money in working and functional fashion though, and were the ones who took high fashion concepts, mixed them with the new concept of “suit” and old concepts of stealing ideas from men and military, and came up with what seems very familiar and regular today, but what was entirely innovative and original back then.

Designers improved fabrics and construction techniques, and added the 3rd piece of the “suit”, which had previouslyl been a boned bodice and skirt with revers in the front which appeared to be a blousewaist (except they didn’t know what a blousewaist was, so it was the revers that inspired the blouse).

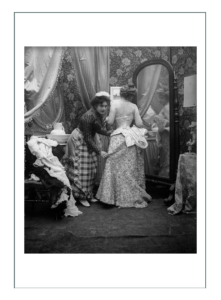

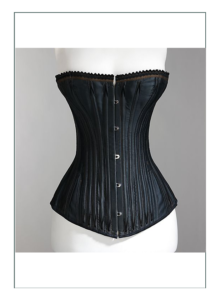

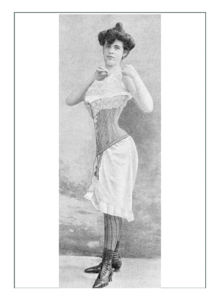

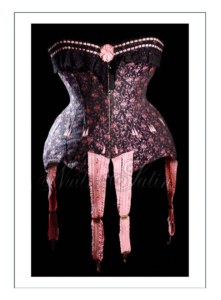

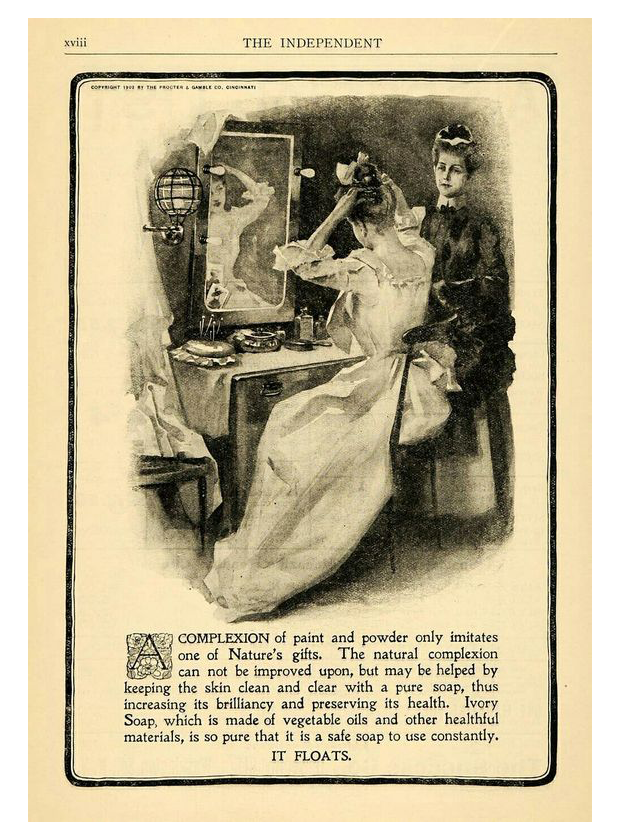

A key concept of the time was that women now could dress themselves, although they needed some skill with the changing shape of their corsets. Corsets approaching 1900 were long and cinching – very tight. Corsets into the 1900’s were long, cinching, and intentionally creating a new shape – the Monobosum – which would eventually evolve into very long versions of what would even later become a girdle and brassiere.

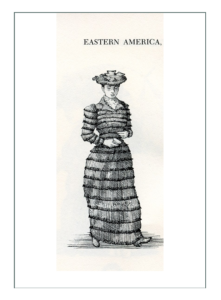

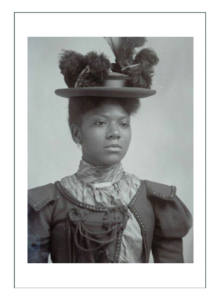

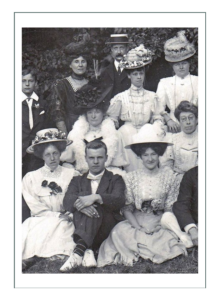

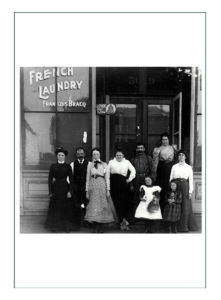

The 2nd key of the time is that all women wore the same thing – perhaps more or less of it, and perhaps made of higher or lesser quality of materials. It was a time when class disparity LOOKED the same. There was, however, extreme class and social structure as America had become extremely diverse, and urban society in particular was multi-cultural.

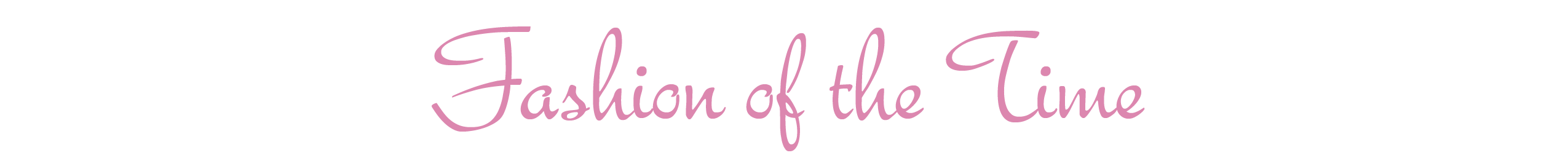

There was then, the West; a world far removed emotionally from high fashion and fashionable counterparts of eastern U.S. and the rest of the world. If the Edwardian Era of Fashion was defined as a MOOD, then Western American Edwardian was like a hosting a wild party.

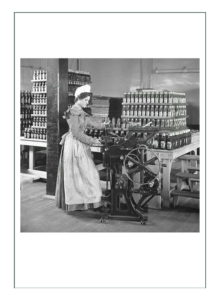

WOMEN & WORK

WOMEN & WORK

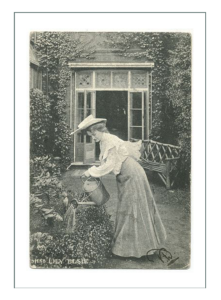

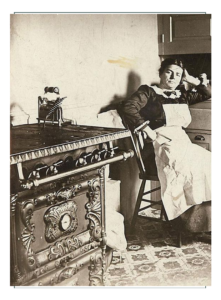

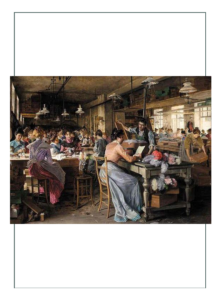

- By the early 1900’s, more & more women were earning livings as governesses, shop assistants, & typists

- Women needed clothing to adapt to many situations & to be flexible for different activities

- The clothing industry was the 2nd largest employer of women, next to domestic service at this time

- It encompassed a wide range of jobs including dressmakers, shirt-makers, underclothing makers, milliners, hatters, glovers, hosiers, straw bonnet makers, collar makers, tailors, pattern-makers, & shoe/boot makers

- Women also made accessories including embroidery, lace, gaiters, fur, & feathers

- In 1871 in Britain there were 300,000 women working in the clothing trades. This number nearly doubled by 1890

- By the 1850’s clothing was still in the hands of small traders such as milliners & dressmakers who were the high end of “needle employment”

- These professions continued into 1900 to exist to serve the new Edwardian lifestyle & it’s demand for quality that could not be achieved through mass production

- Successful “needle women” had assistants & apprentices. A good business woman might have a workshop or store built on to her house

- Due to the increased costs of establishing a business, & the separation of work in factories, fewer girls were going into the clothing trades as time went on, making those still working more value, yet undermining the ability of dressmakers to do quality work because they were short of help

- Millinery, for example, took 7 years of unpaid work during which time the apprentice was required to pay fees. It was therefore always a father’s decision whether to pay for his daughter to be apprenticed. Many fathers of the time did not want to invest that much in a daughter

- Being a day-worker or journeyman in the clothing trade was not lucrative because every girl was taught to sew, & sewing was always the first resort if a woman needed to earn money

- Sewing was a convenient job a middle class woman could take up without loss of face or status

- Because of the high availability of labor, hours were excessively long & pay very low in the garment & textile industries except for those at the very top, such as the Haute Couture houses

- Upper class ladies still kept a few top quality dressmakers well employed in creating, ornamenting, mending, & altering garments

- Manufacturers of headwear did a roaring trade, selling ready-made as well as custom orders to all price points & classes

- As well as hats & bonnets, a milliner made caps, cloaks, mantles, gloves, scarves, muffs, tippets, handkerchiefs, petticoats, hoods, & capes

- During an 1834 tailor’s (men’s) strike, the local needlewomen took up the dropped work. Refusing to give the work back to the tailors after the strike, the women continued as tailors, many marrying the men who then worked as their assistants

- Stays & corset making throughout all eras & situations, however, remained strictly a male enterprise due to the considerable physical strength required until equipment was invented to take on the heavy work of hand sewing

- Women who went into corsetry employed men to work for them, & typically they were family run operations

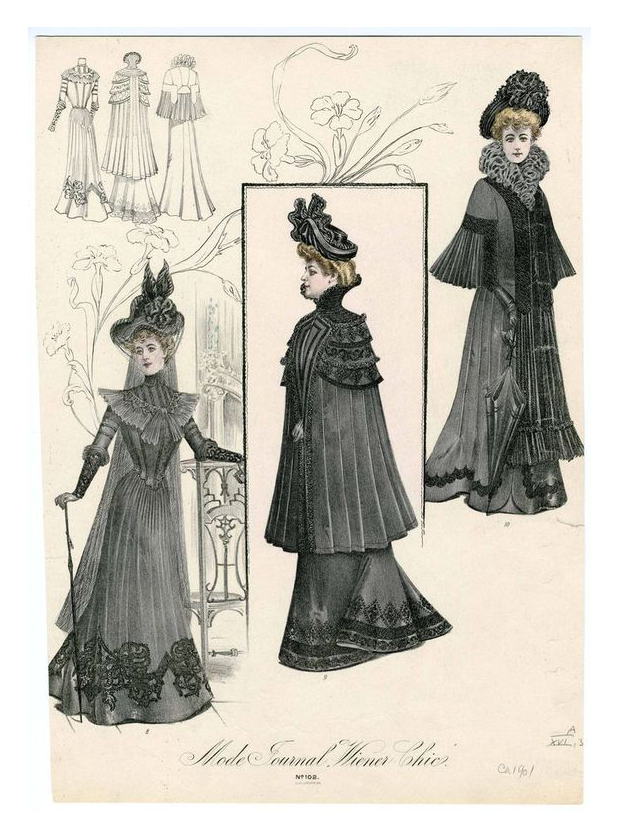

—— FASHION TRENDS ——

THE SILHOUETTE

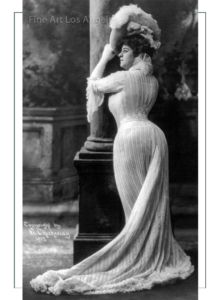

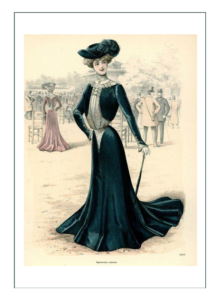

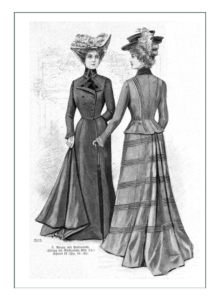

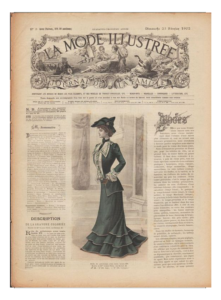

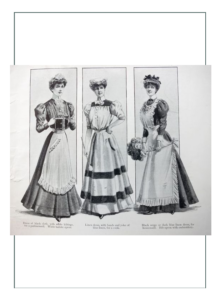

- By the 1890’s & until 1910, the gored skirt looked more tailored & matched the jacket style which followed the changing silhouette of the time

- In 1895 in particular, the tiny sashed or belted waist was balanced out above by giant sleeve heads, & below by a simple flaring skirt

- The jacket, shirt-waist, & skirt would evolve into “waist-less” straight garments by 1914

- The concept of the jacket, skirt, blouse/shirt-waist, belt & well-tailored lapels & details would remain despite changes in the silhouette or line of each era

JACKETS

JACKETS

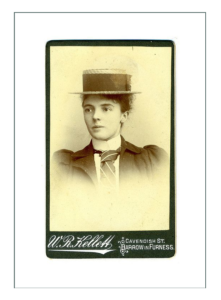

- Initially , in the 1880’s a “suit” jacket was tailored & worn with a draped bustle skirt

- The English tailors Redfern had taken the concept of the 2-part ensemble with fitted bodice & skirt, & made it into amore uniform look

- “Suit” in the beginning typically meant a fitted bodice which followed the silhouette of the day, above a matching skirt which also had the profile of the day

- The total ensemble of Redfern’s “Tailor-Made” suit came to mean a coat & skirt, worn with a blouse in the 1890’s to 1900

- Early suits could have matching or contrasting fabrics for skirt & jacket

- They did not create an overall image, but still looked like a dress with jacket

- The longer line of the jacket continued to be developed as time went on

- This long, powerful line distinguished the suits of the day from previous & later versions

- Later the skirt always matched the jacket, & it made one long visual line

- The jacket profile became straighter & less waisted towards 1910

- The short bolero, worn instead of the full jacket, was popular in Western & Southern US regions

- Boleros were short sleeveless & collarless vests that covered the top of the torso down to only about the ribcage

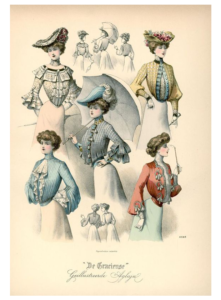

SHIRT WAISTS & BLOUSES

SHIRT WAISTS & BLOUSES

- The “shirt waist” was an invention of multiple fashion houses, & evolved from the “corset cover” which was a sleeveless or short sleeved blouse that was often seen on the outside of the garment

- The “shirt waist” in contrast to the tailored, thicker, & often darker in color suit was always of a light, gauzy fabric

- Lawn, voile, handkerchief linen, or silk or taffeta for dress occasions were favorite fabrics for “shirt waists”

- “Revers” & chemisettes, worn in previous eras & through this era, were like false fronts of a blouse. These were worn with the first suits, & preceded the full “shirt waist” (later called blouse) concept

- “Shirt waists” followed the profile & silhouette of the day

- In the 1880’s to ’90’s they had multiple tucks down the front with rows of buttons which ended in a standing collar

- 1890 to 1900 saw the blouses loosen significantly so they were more gathered at a smaller standing collared neck. The fullness would expand towards the waist, where a wide belt or sash would gather it in to the stylish below waist profile

- Consistent with Edwardian style, many “shirt waists” for suits around 1900 were very lacy & ornamented with ruffles, pleats, tucks, & pearl buttons

- As the 1910 style evolved into the long waisted & long corseted look, the suit “shirt waist” followed the same line

- These were of the same light & gauzy fabrics as the dresses, & many were of beautiful colors in silks & cottons, as well as the new synthetic fabrics

- “Shirt waists” of the 1910-1914 period were often of woven or printed patterns worn under a plain but beautifully richly colored suit jacket with skirt

- Asian and Eastern influences which had affected fabrics & patterns of “Art Nouveau” & “La Belle Epoque” were seen in the lovely loose draping & colors of the “shirt waist” of this later period

- Removable collars & cuffs had been worn throughout the Edwardian period. They were not necessary after the “shirt waist” replaced them as an entire blouse garment with its own collar & cuffs

- Necklines were consistent with the dress necklines. At first they were buttoned with high collars

- As necklines dropped to the “V” and square or rounded shape for the dress, they also did for the “shirt waist”

- Eventually sportswear such as tennis dresses would replace the suited “shirt waist” to become the entire tunic dress

UNDERGARMENTS

UNDERGARMENTS

PETTICOATS, CORSETS, & BRASSIERES

- In 1902 it was considered vulgar to hear your petticoat, but at last it was permitted to be SEEN

- Petticoats were worn less & less from 1899 to 1914 in favor of underlinings, double fabrics, & long corsets

- The growing interest of women for sports & women entering the work force made comfortable, moveable, & breathable clothing necessary for all classes

- Designers responded to women’s increased activity by modifying clothing design plus production techniques in both custom & mass production

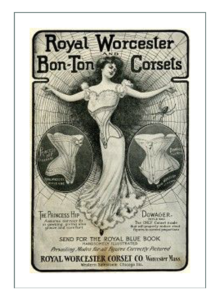

- The corset industry in particular responded by creating multiple types of corsets for specific needs & for specific body types

- Even corsets being mass produced had a large variety of shapes, purposes, sizes, & modifications to meet individual needs

- Catalog corset sales were a BIG business

- There were many, many corsets available of every type for every activity from active sports & special riding or health corsets, to handmade boudoir silks worn by performers (with nothing else) on stage

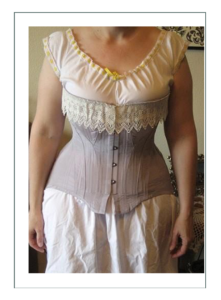

- By 1909 beneath the new straight gowns, women wore corsets that began under the bust & extended well down over the hips

- The fashion objective starting in about 1904 & with momentum in 1909 was a long, columnar line, so corsetry was less focused on restricting the waist & more on smoothing the hip

- The new everyday undergarment became the “brassiere”, with an era of relative freedom from understructure until the rubber girdle

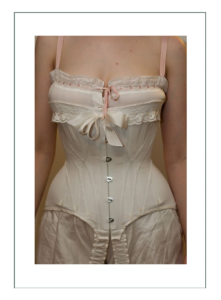

- “Bust bodices” or “brassieres” supported the bust for those who did not wear a corset

- In 1910, early Brassieres looked somewhat like corset covers – sleeveless, white cotton garments that ended anywhere between the bottom of the bust & the waist

- They could be boned or unboned, depending on the amount of support needed

- These provided a soft foundation that could go higher than the Edwardian monobosum, but still lower than our modern silhouette

DRAWERS & CHEMISE COMBINATIONS

DRAWERS & CHEMISE COMBINATIONS

- Undergarments for activewear were much the same as for fashion

- Suit undergarments were the same as per the fashion silhoutte of the day

- Specialty activewear would have a modified version of chemise, drawers, or combination

- Activewear, other than suits, did not typically wear a petticoat

- Drawers & chemises were combined in 1877 & called “combinations

- By 1890 the chemise & drawers were replaced by combinations entirely, because they reduced bulk around the waist where women were aiming for a completely smooth line from chest to knee

- A combination was a camisole with attached knee or calf length drawers

- Combinations were worn under the corset, bustle, & petticoat

- Woolen combinations were recommended at the time for health, especially when engaging in fashionable sports

- The old knickers persisted; sometimes in wool or even chamois leather for sports

- Both new & old styles of knickers fastened in the back or at the sides with 1-2 plackets, or with a falling back flap which buttoned at the waistband

- As with ordinary drawers, the combination or one-piece left the crotch seam open

- Flap-fastening drawers were closed at the crotch seam under sporting costumes

- Combinations were worn even under swimwear until 1907 when they swimwear was made of tight knits

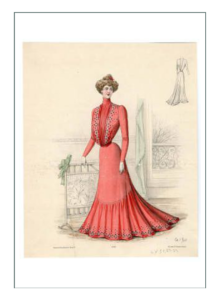

FABRICS & COLORS

FABRICS & COLORS

- Early traveling & work wear suits were in cottons, wools, & especially wool serge

- Designers added more fabric choices & colors quickly in response to demand for traveling suits

- “Tailor-Made” suits were ideal for traveling, & became more versatile, so more fabric choices were added

- Heavier fabrics like tweeds & serge became popular for every day work or wear in the country

- Further innovations & variety of fabric & design were added to make suits “suited” for formal affairs like weddings

- Heavier fabrics like wool, tweed & serge were expanded upon using lighter weaves for suits worn for everyday work or wear in the country

- Higher end suits might be blends of natural fibers such as cashmere

- The new synthetic dyes could be used, but the natural fibers lent themselves well to natural dyes, so colors tended to be more “natural” than what was being used in light gowns & other types of day wear

- Suits of the 1870’s into the ’80’s favored lighter colors of beige, tan, light gray, & a variety of greens & blues

- Suits of the 1880’s into 1900 were much darker & included blacks & grays, dark browns, deep olives, dark burgundies, & shades of navy or teal blue

- Suits were especially darker & heavier overall in appearance than all the other Edwardian & “Belle Epoque” trends

AND SO/SEW FORTH

AND SO/SEW FORTH

- Collars & cuffs were still used, although with the introduction of the “shirt waist”, they became redundant

- Belts were either straight or had a slight V at the center front pointing down

- Belts were made of leather, or of a contrasting fabric, often black or brown

- Washable kid gloves were worn everywhere

- Suede & silk embroidered gloves were worn for formal occasions

- Ladies carried little money as goods were always charged to accounts & minimal make up was used, so they didn’t need large handbags

- Small dainty decorative bags with a strap that hung from the wrist were sometimes used, but never handbags

- In 1913, women were finally allowed to have integrated pockets in their clothing (all prior history pockets were attached or hung on the body)

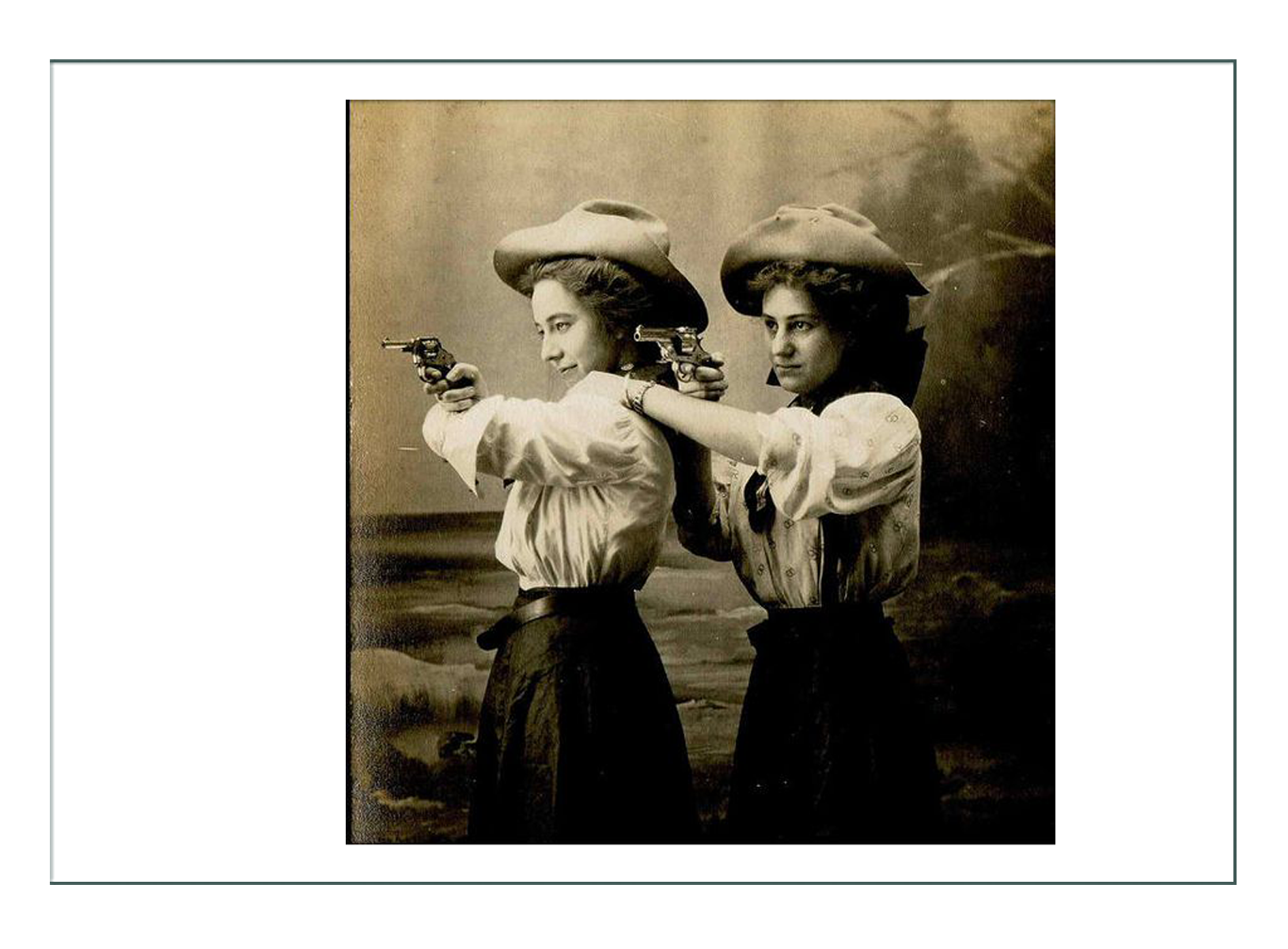

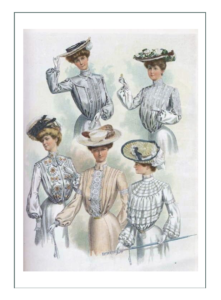

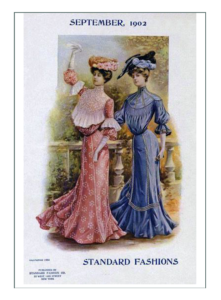

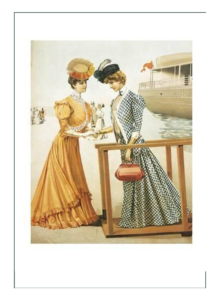

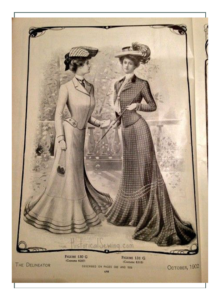

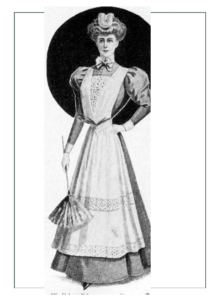

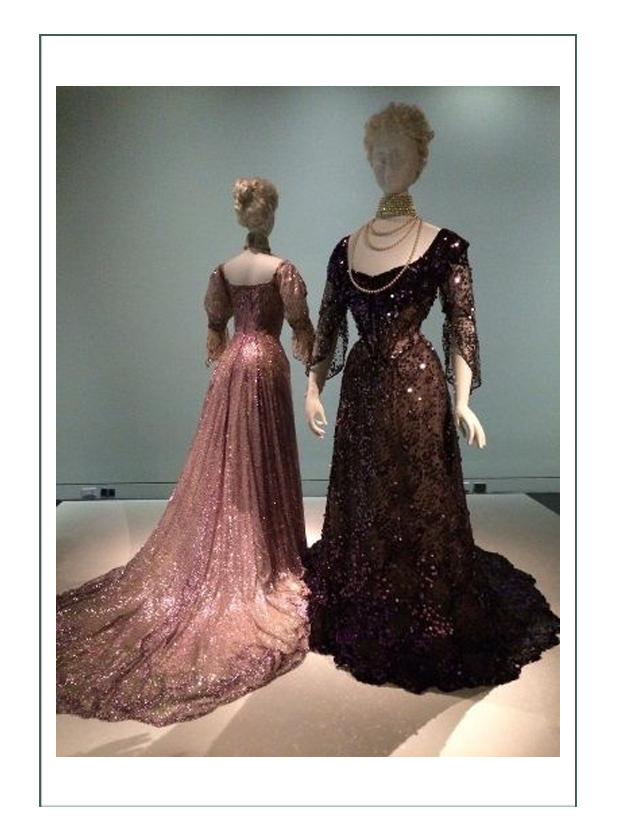

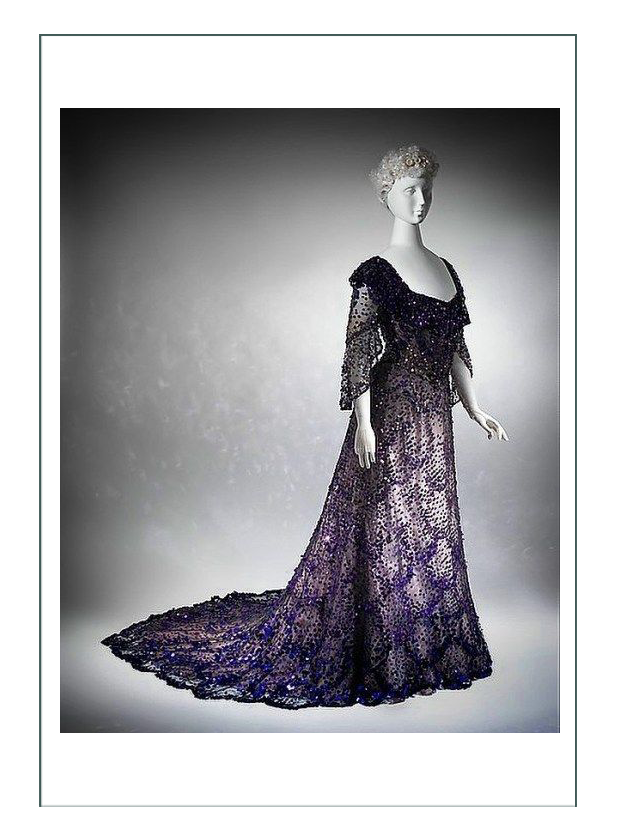

High Fashion Examples of 1902

The Silhouette

Skirts & Blousewaists

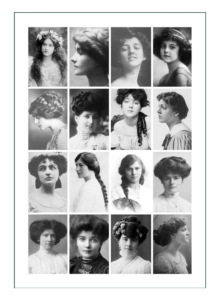

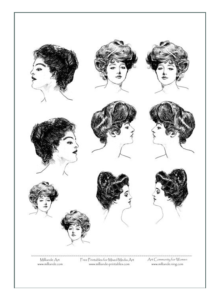

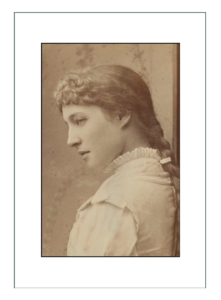

Hats & Hair

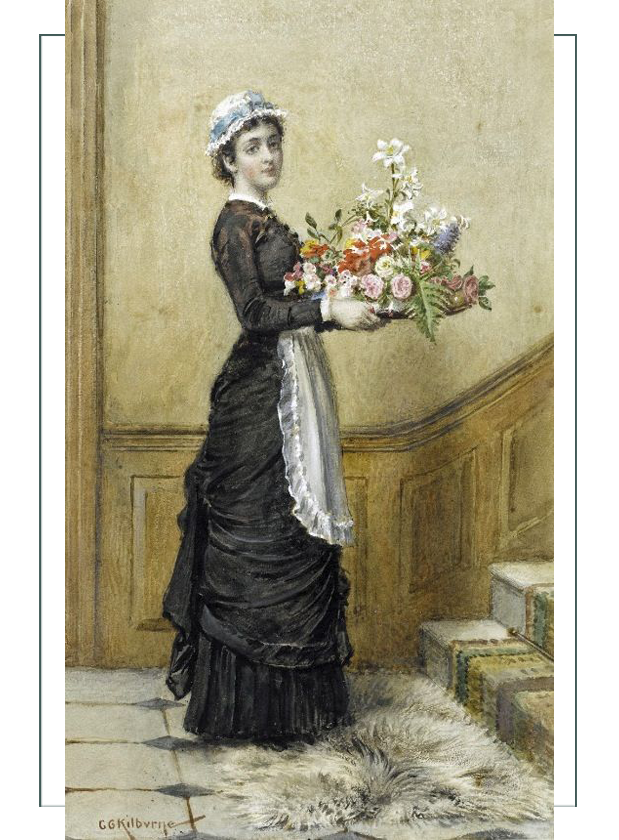

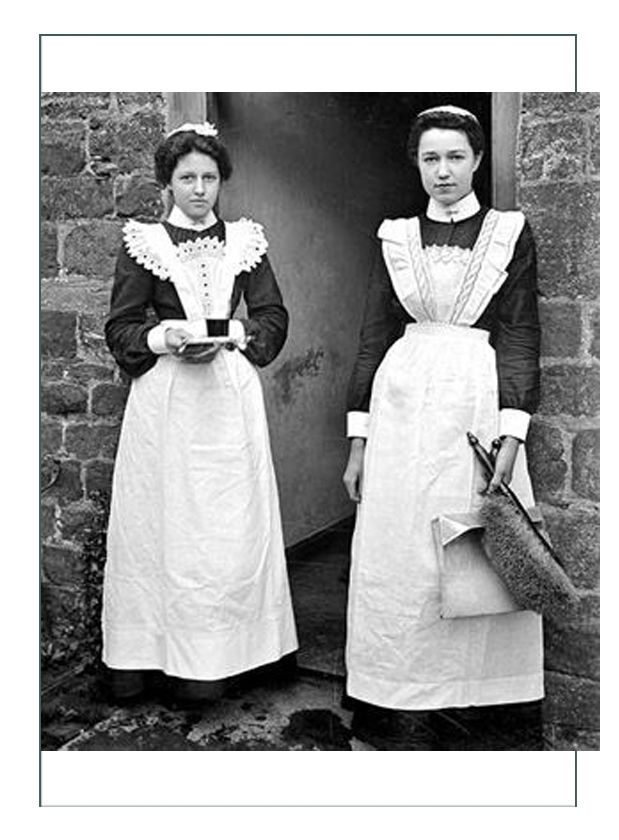

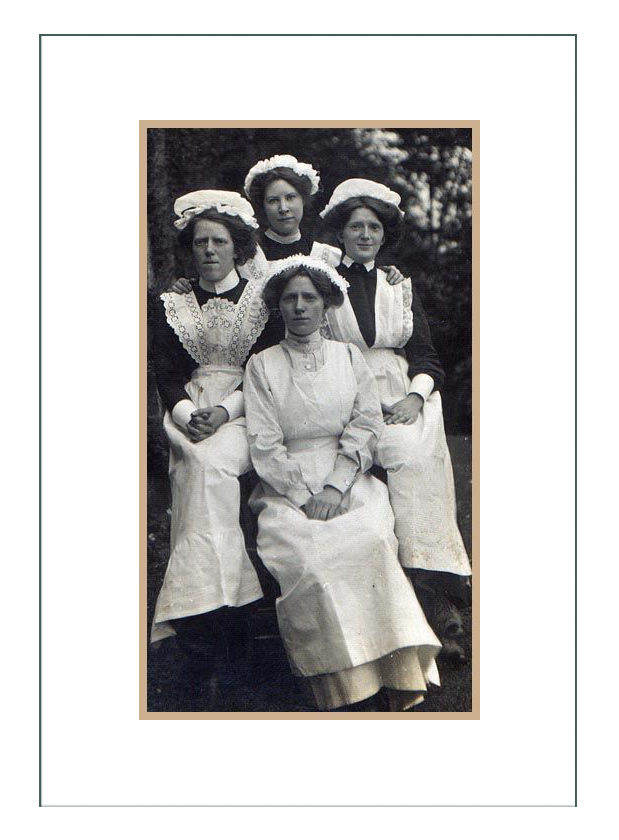

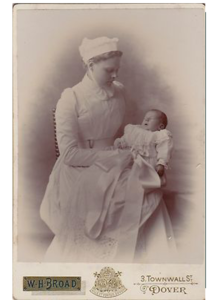

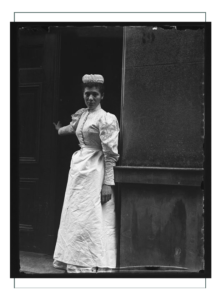

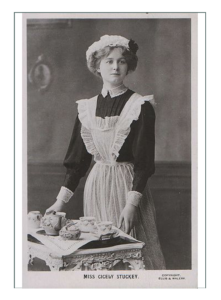

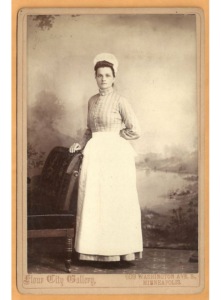

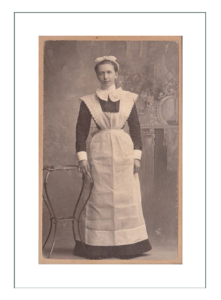

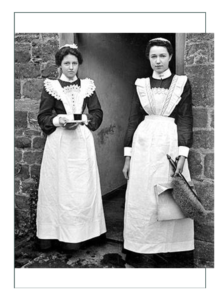

Nurses & Maids

Nurses & Maids

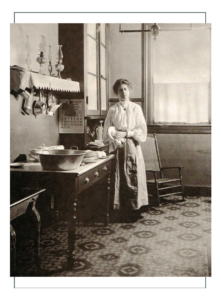

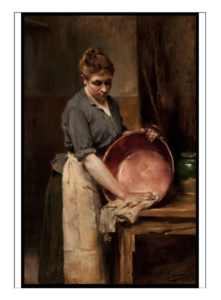

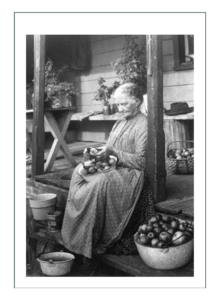

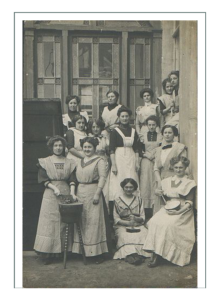

Who were the Maids?

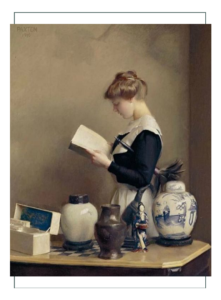

The role of domestic servant or Maid, has long been glamorized by painters and poets as a service to mankind. Little record is kept by maids and domestics themselves, so we can only assume it did provide good feelings of service, developed relationships between the family and workers, and provided a modicum of income, especially for young women, widows, unskilled, or otherwise unemployable women due to race or ethnicity.

Race and ethnicity did play a role in deciding whom would be employed as domestics. As it had been since the late 1870’s, women were still mostly employed in service industries in shops and factories but only until marriage. Black Iris, and Swedish adult women were the servants. In the northeast cities where wealth, and so potential employers lived, Irish women Catholics were predominantly the servants

Department stores were almost all shipping for middle class women even into rural areas across the country. When a woman went into a department store, she was always served by an employee who was a middle class woman. The worker would quit when she married, except African Americans and Irish Catholic Women who kept working even after marriage.

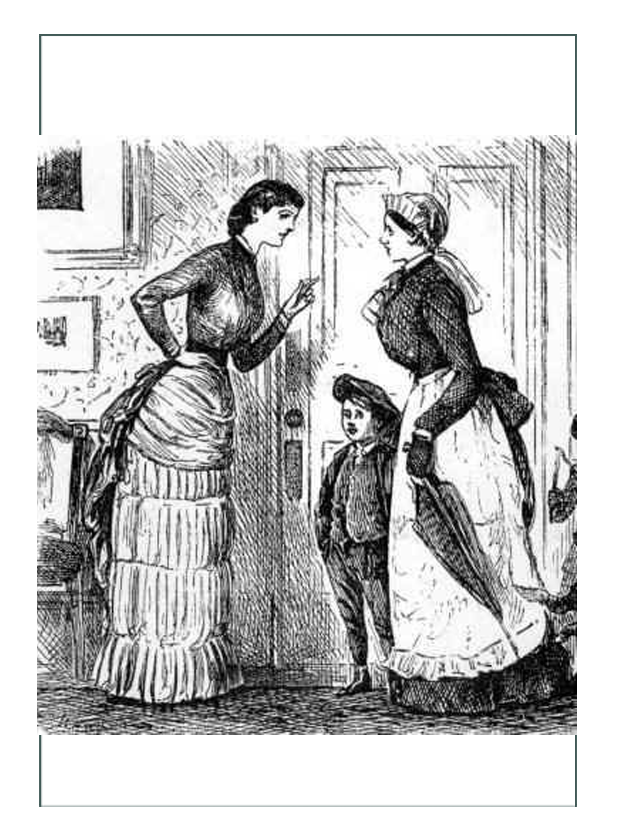

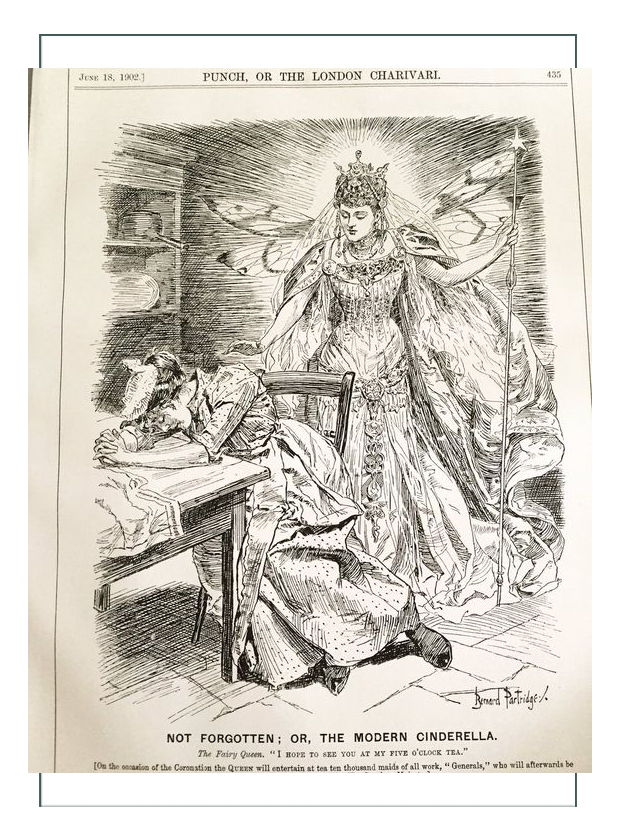

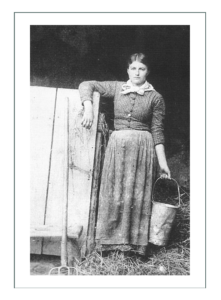

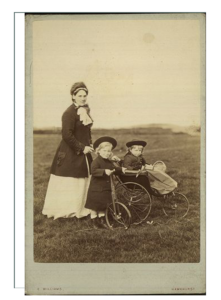

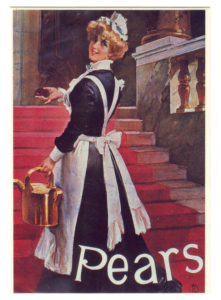

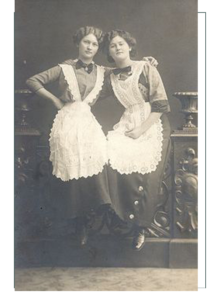

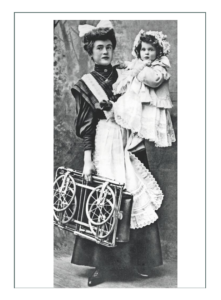

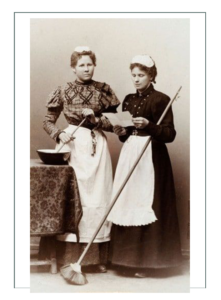

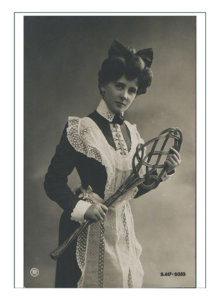

The first cartoon above from the late 1870’s jokes about how close in style the clothing was between servant and served. The second deals with social class distinction. Some claimed in that late Victorian into Edwardian Era that it was the attitude and social position that made the difference, not the clothes. This is somewhat true, as working women followed the same rules and dictates of high fashion at all class levels; they just did it on a much lower budget and with some additional rules.

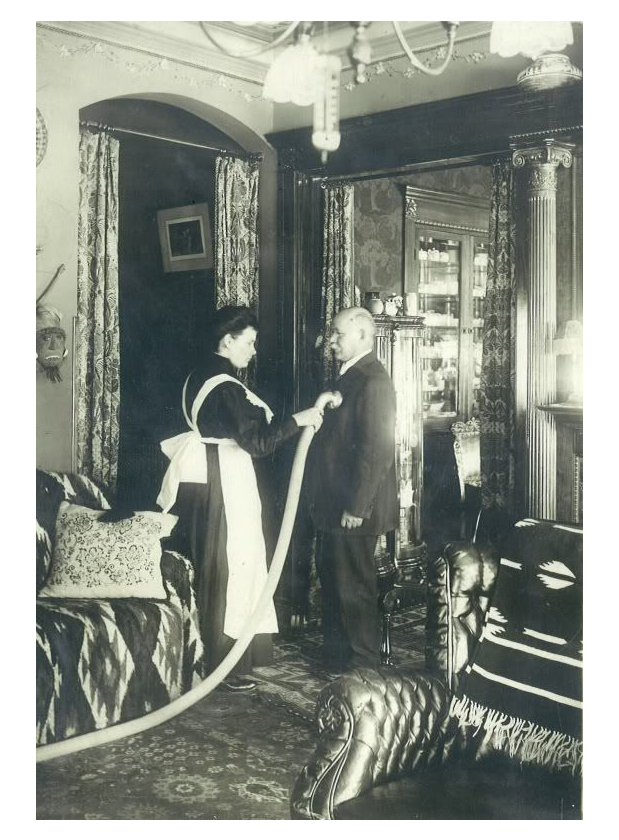

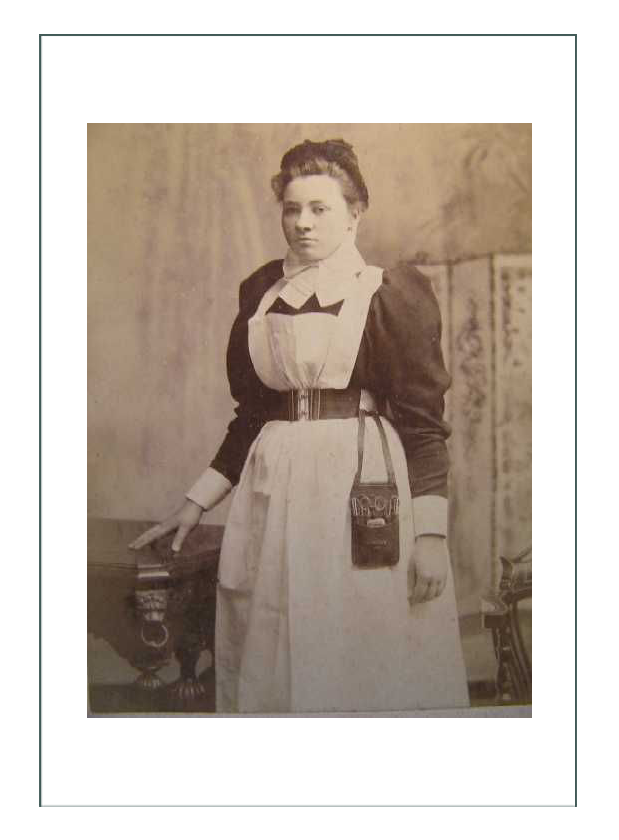

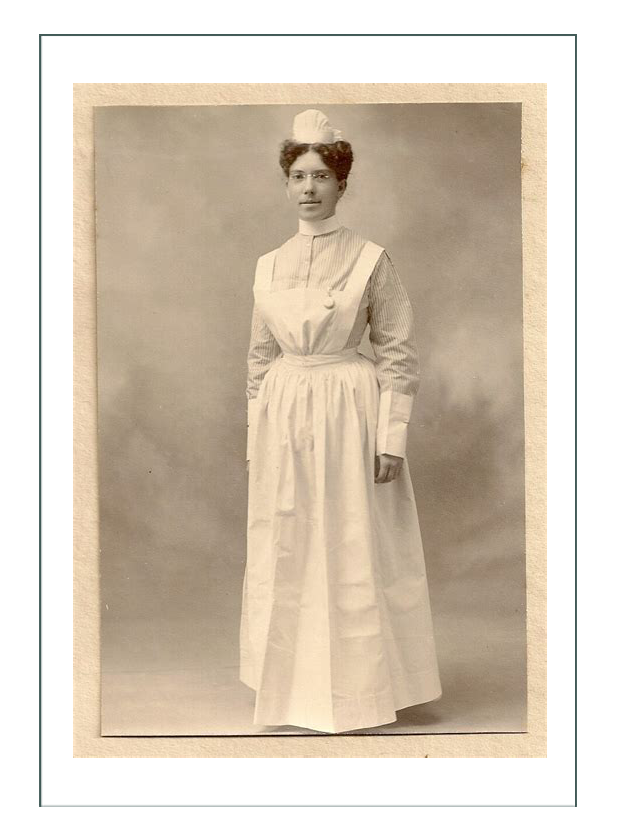

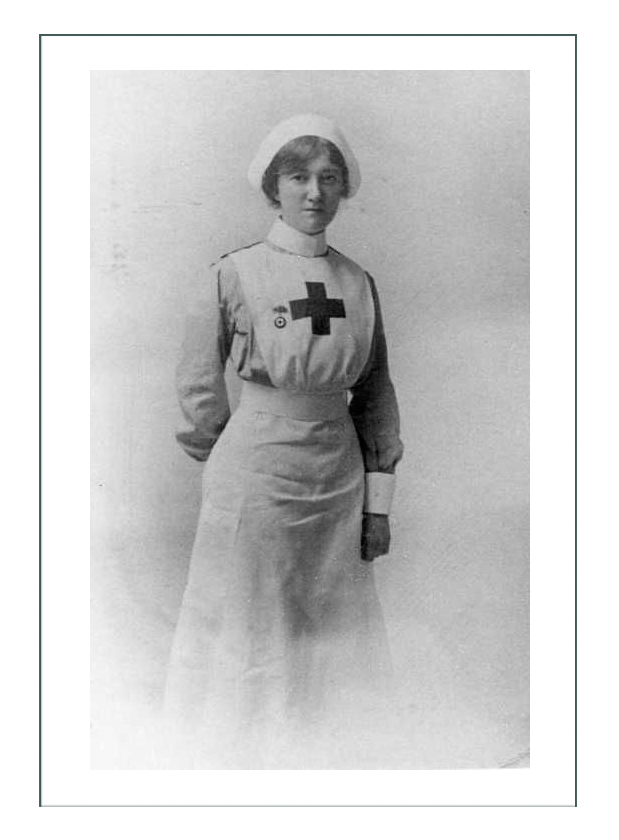

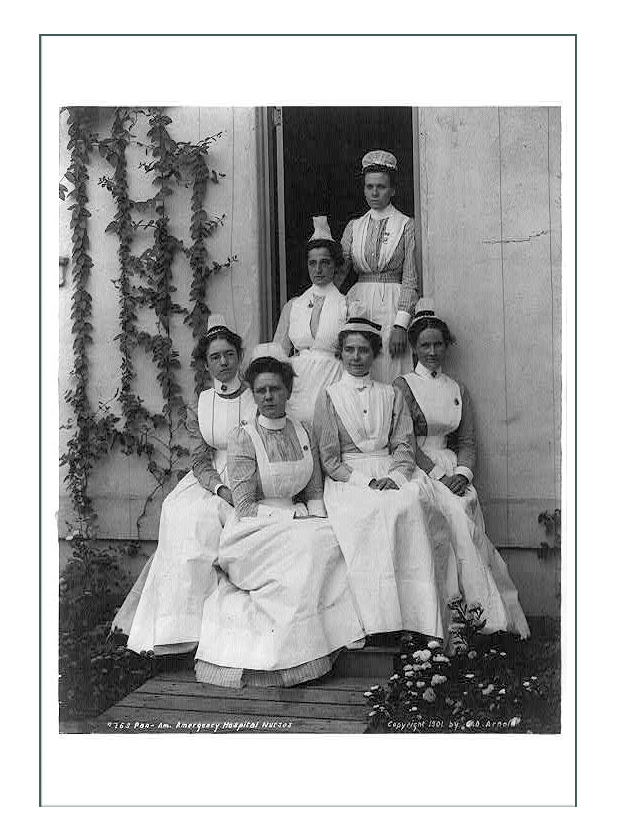

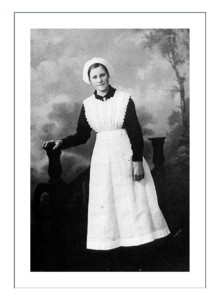

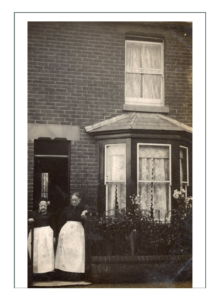

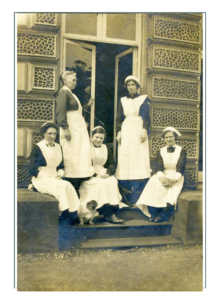

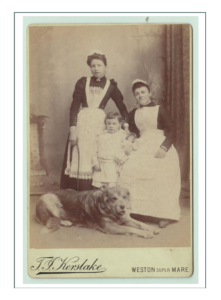

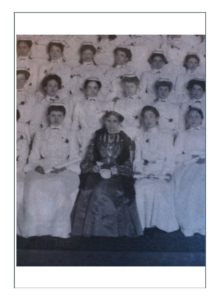

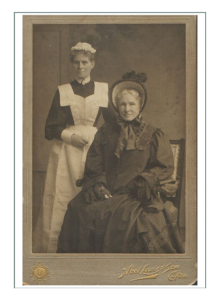

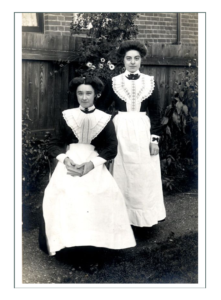

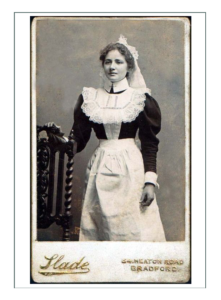

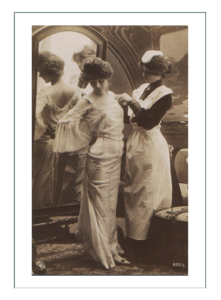

Domestics (Maids) and Nurses wore basically the same thing since the profession of nursing began unofficially in 1855, and progressed exactly the same until about the 1960’s when the nursing profession was redefined, and maids no longer were considered a “lower” profession. It is today very difficult to tell the two apart from photos or depictions (nurse left; maids right both late 1890’s):

A History of Uniforms

Uniforms evolved over time. Early healers did not wear anything to set them apart. In the Middle Ages when religious orders were involved in the caring of the sick, the nun’s habit became assoicated with nursing work.

As nursing turned into organized disciplines in the 19th century, the flowing robes of the nun persisted worldwide. This would influence the design of uniforms for hundreds of years.

19th Century – Design with Purpose

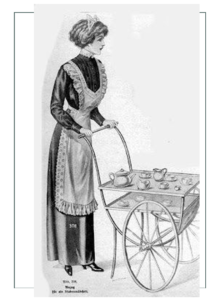

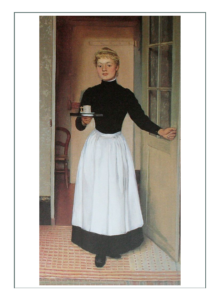

Uniforms were designed to identify the person with a specific institution of learning, teaching, or nursing practice. Pride in belonging to a prestigious hospital had some uniforms with flamboyant designs such as huge sleeves or giant skirts, although all along the silhouette typically aligned with that of fashion of the day. They more closely resembled whatever domestic servants were wearing at a given time, which was usually a version of high fashion.

Color and style were used symbolically – white for hygiene and cleansiness, blue for purity, and pink for femininity. One of the most striking and memorable use of color and symbol in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was the Red Cross’ with its emblazoned red cross. It designated humanitarian aid to battle wounded on either side of a conflict.

A combination of practical, political, and symbolic, bands, stripes, and colors were used to differentiate between ranks. By the end of the 20th century, those bonds were broken in the invention and use of “scrubs”, which were practical and unisex.

Late Edwardian Uniforms

When Florence Nightengale, the founder of the profession of nursing as we know it today asked Redfern to design a uniform for her corps in the Crimean War, the company met her deadline and specifics to create the “look” we know today. Unfortunately, Redfern forgot to ask for measurements, so none of the uniforms fit.

Women’s clothing became more tailored and designed to make a statement as the concept of ready made meant taking a garment off the rack of a department store, and having it fit to you.

American high fashion design company Redfern had invented the “yachting suit”, which was the first branded sportwear. Women wore 3 piece “suits” in the workplace so they could feel powerful as they blended in with the men. It’s no wonder men found them “unladylike”.

Uniforming reflected fashion and the class or status of a nurse. You can see in 1910 uniform silhouettes the remnants of the old “monobosum” with its padded rump and bosom, but now it has a lower waist and a longer and straighter line.

Fashionable blousewaists were typically of simple printed cotton, and somewhat tailored. Early ones had removeable collars and cuffs with celluloid standing tabs, but as ready made and washing machines progressed, collar and cuff became integrated with the blouse.

Split drawers are very basic and strictly functional sanitary white cotton, worn just for modesty under uniforms.

Aprons

The function of the nurses apron is clear in protecting the clothing and being easy to put through stringent and oft times washings. It’s stiff starchiness indicated nursing status and symbolized “purity”.

As with the Red Cross, a volunteer organization which required women to make their own uniforms, design and details of aprons varied by individual and hospital. There are no patterns and no designs; only photographs.

Caps

Caps in particular reflected the evolution of nursing. They show how nurses were perceived, and what their roles were at different times. Early versions were like a nun’s coif made from starched white material.

In the USA by 1900, nurses wore a mob or maid’s style cap that was influenced by domestic servants’. Caps became sharper and less flowing as time went on.

They held symbolic value, especially in the field of war when they retained a nun like veils to denote their purity and to set them apart from the chaos of war. but as germ theory emerged, were also a practical part for cleansiness and to hold all the hair back from the face.

Unique and sometimes intricate styles were dsigned by individual schools or hospitals to give a clear identity. Colors or stripes were used to indicate grade, status, or seniority. As illustrated below, the distinction between a nurse (left) and a maid (right), was blurred, and even their status symbols were the same:

Real Maids 1890-1910 (Advertisements & Museums)

Caps & Aprons

Undergarments

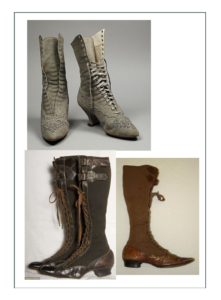

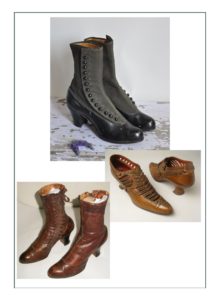

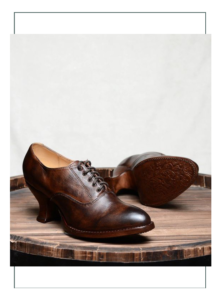

Footwear and Misc.

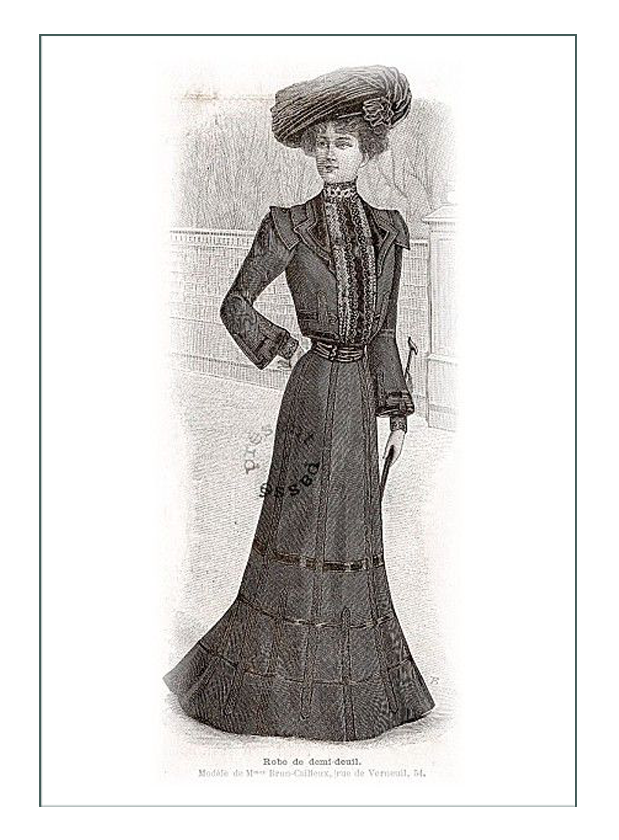

MOURNING – Rules for Royalty & Maids

MOURNING – Rules for Royalty & Maids

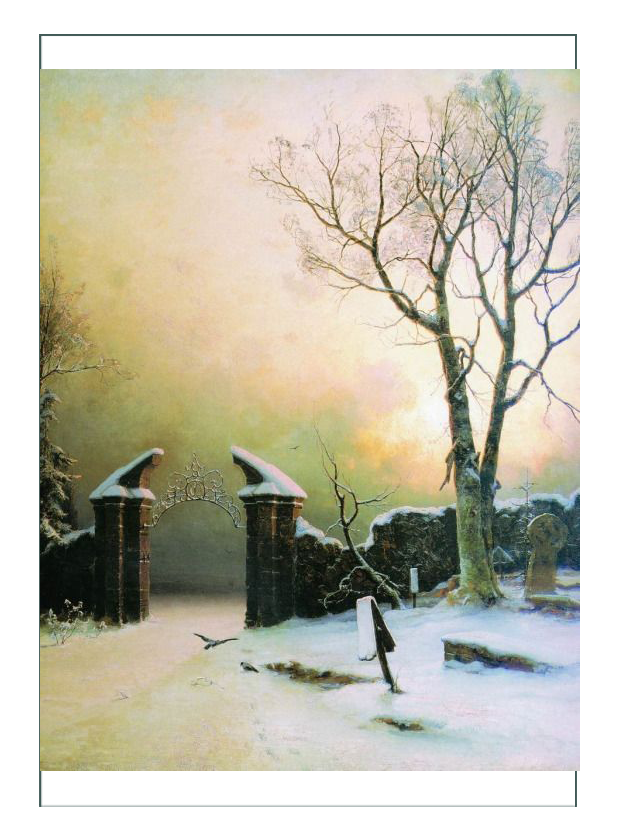

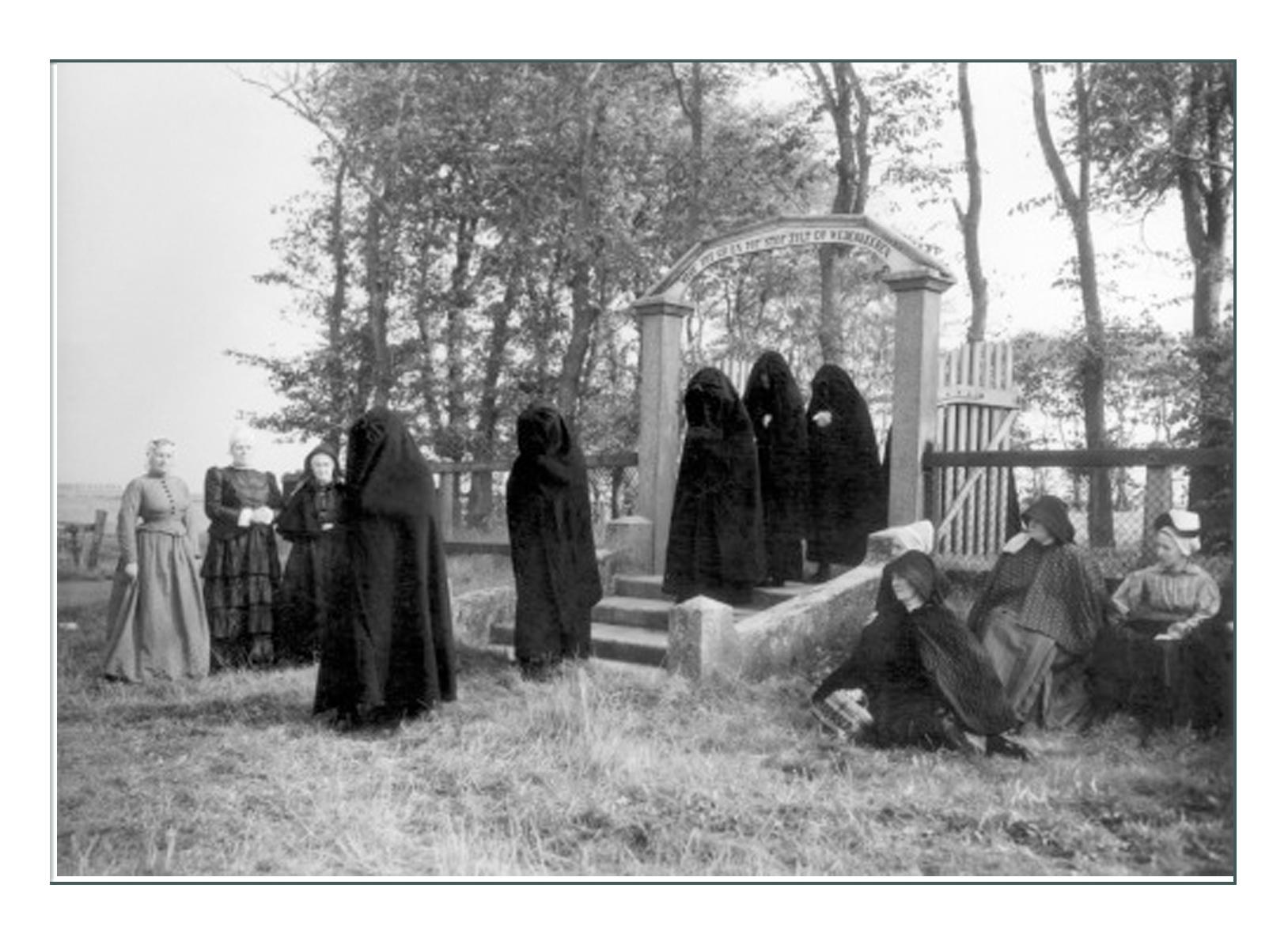

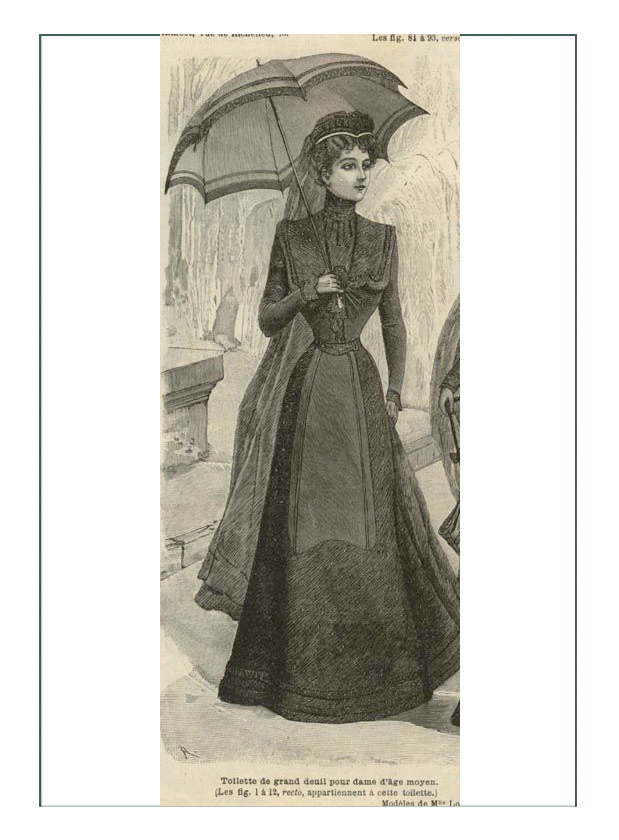

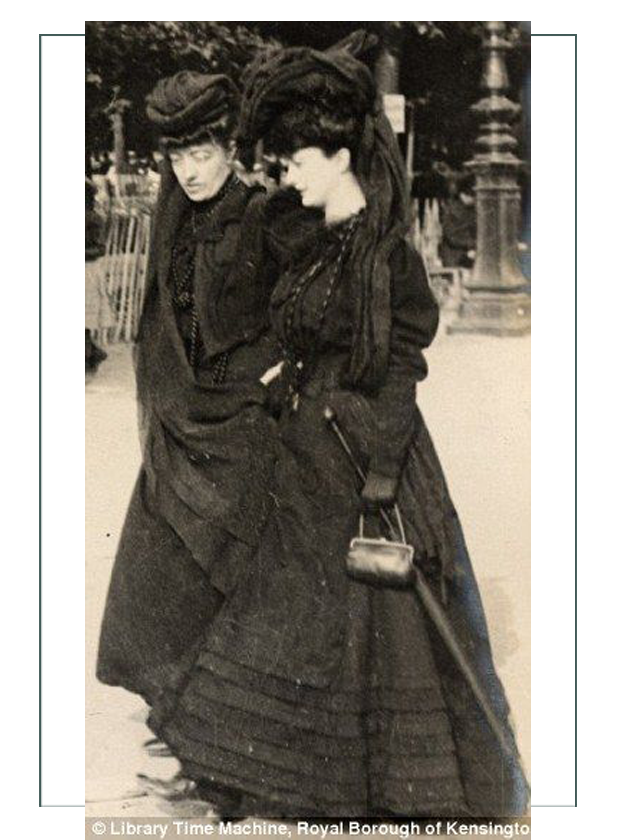

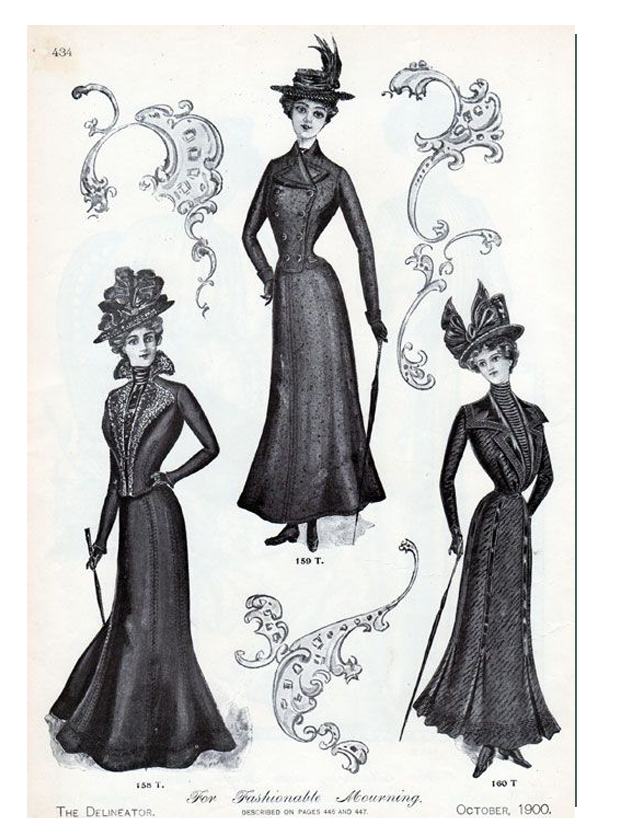

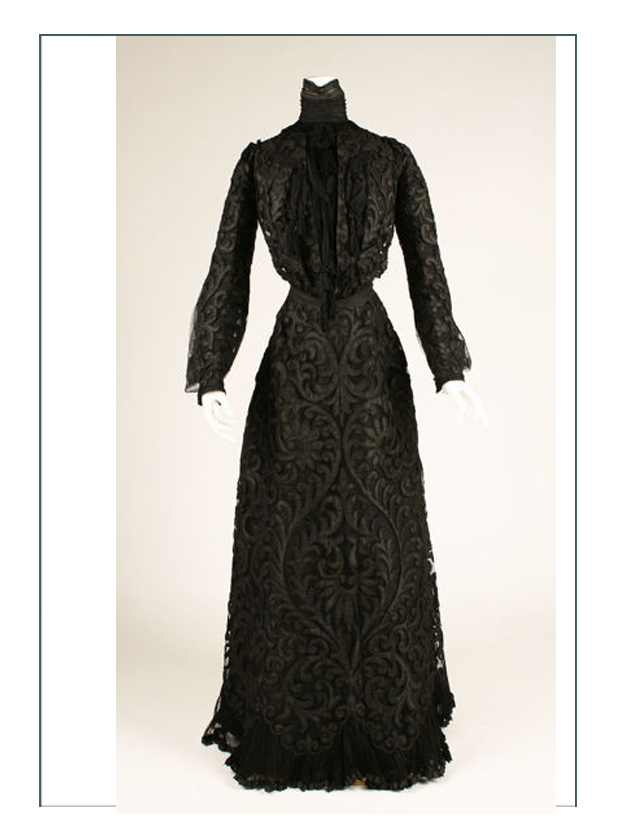

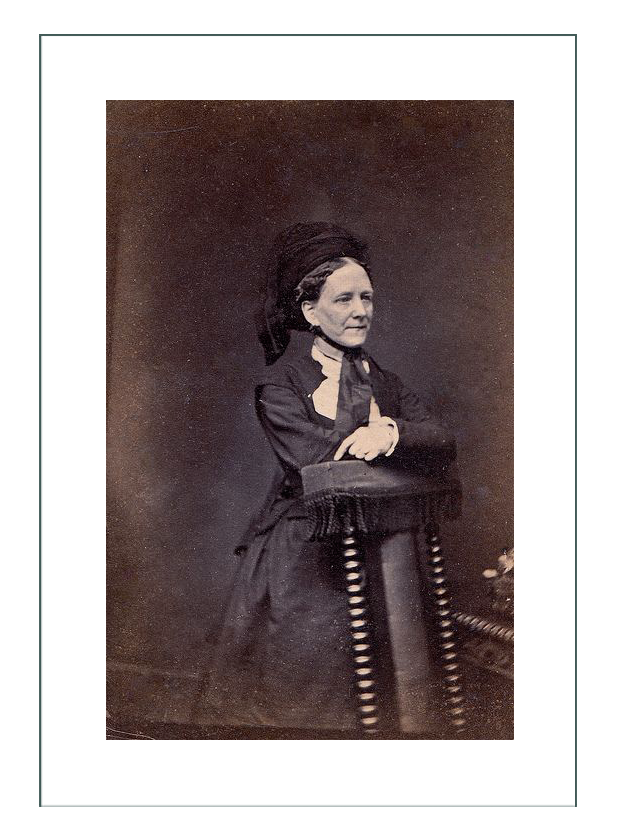

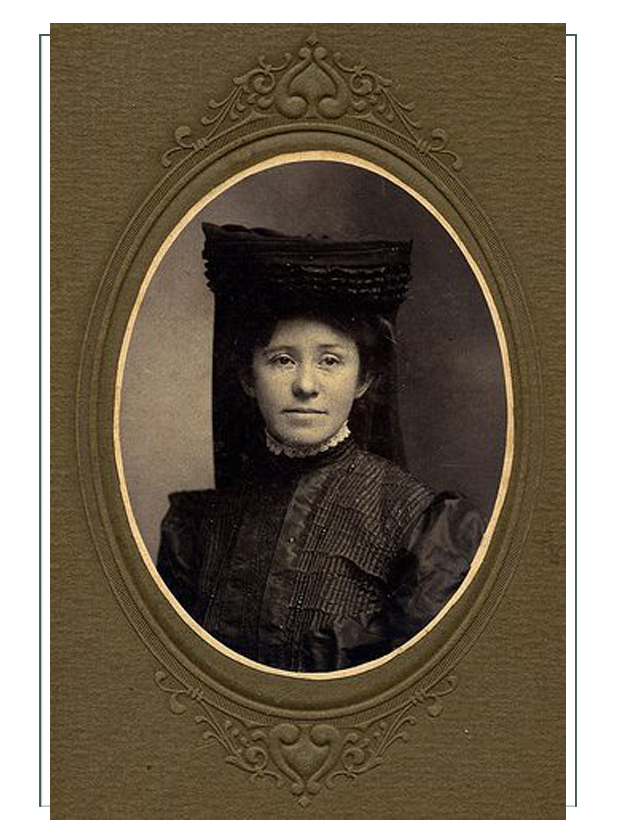

Mourning dress was considered in the Victorian era to be “protection against thoughtless and cruel inquiries and the judgement of society”.

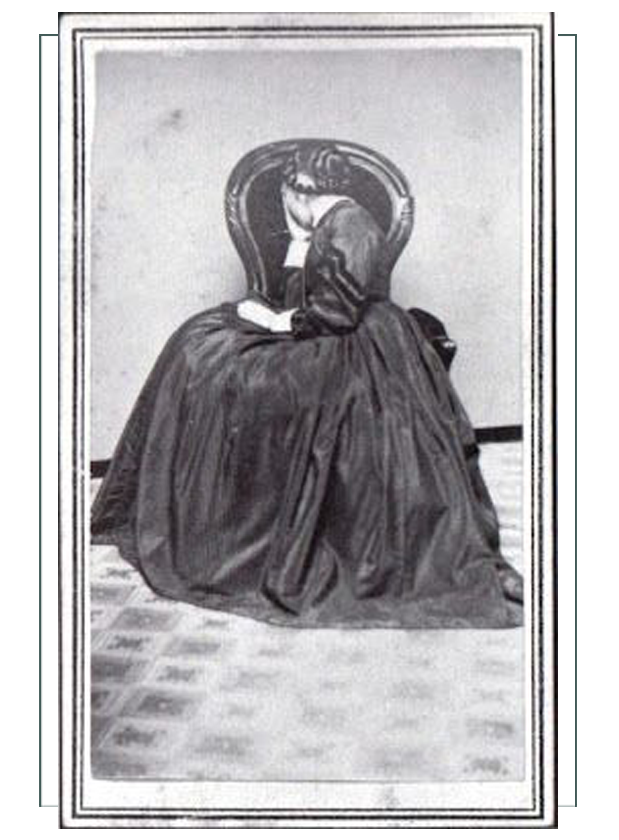

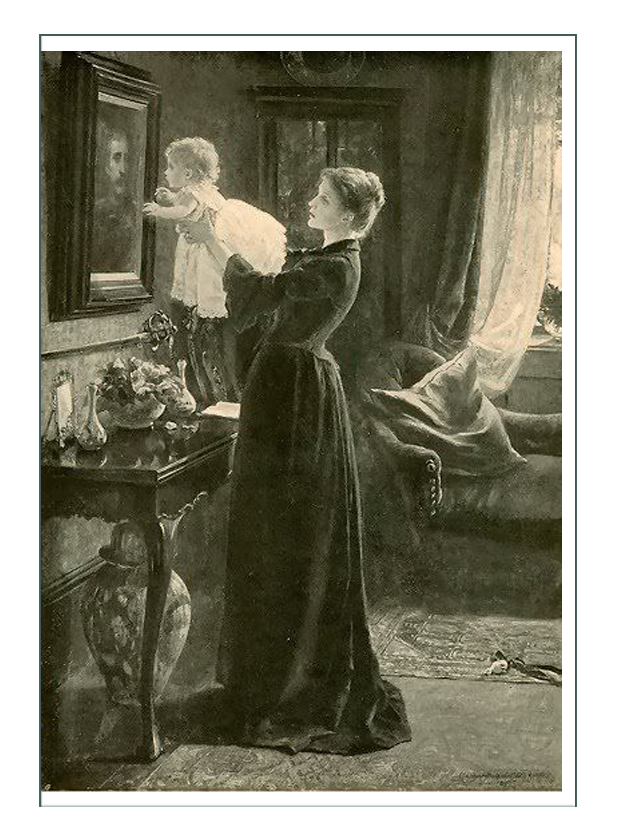

Victorian rules of mourning, as established by Queen Victoria at the death of her beloved Albert in 1861, were hardest on women. Women were considered to embody the spirit of grief, and were required to take at least 2 years away from society according to a specific set of rules and restrictions. The widow was the centerpiece of mourning. Women were considered the social representatives of their husbands, and so it was natural that they should take the central role in organizing and implementing mourning traditions.

Magazines gave constant advice to women to “put aside all the ordinary clothes and (wear) nothing but black in the appropriate material sand with particular accessories for the stages of mourning” wrote one fashion magazine of the 1890’s. There were manuals like “The Queen” which taught Victorians how to mourn.

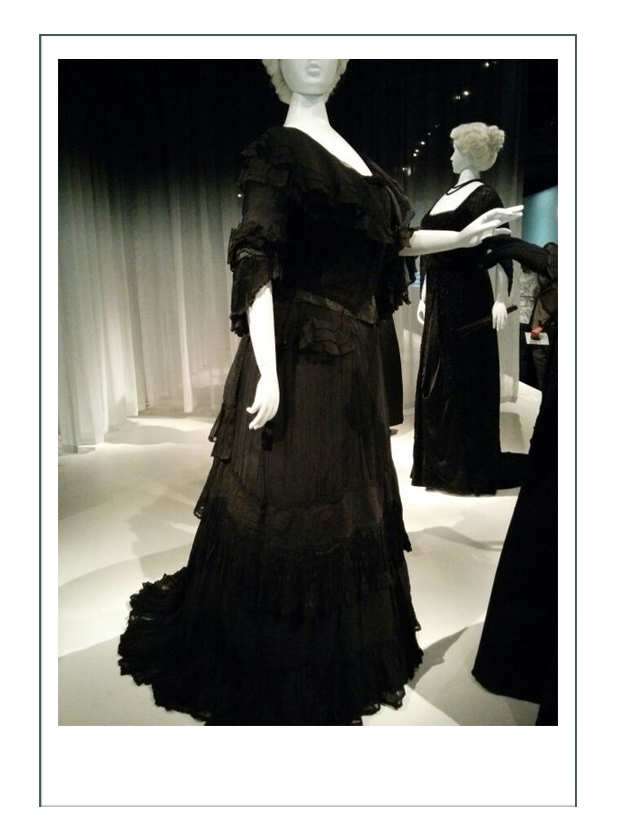

Mourning customs were expensive and wasteful, but they were FASHIONABLE; identical to high fashion of the day.

All classes practiced the process; especially the middle class who wanted to be accepted by higher classes and nobility (see Historical Context for social strata discussion on previous page). The industrialists in particular were fond of sending out black notecards and invitations advertising their adherence to the rules. There were prayer books and handkerchiefs; bibles edged in black leather as mementos of the occasion. They had bands of black and purple around bottles on their dressing tables as well as the necks of their pets and children.

Children were required to mourn for 9 months in full mourning, and then 3 months in half mourning. Full mourning for a woman was roughly 2 1/2 years minimum, or:

Children were required to mourn for 9 months in full mourning, and then 3 months in half mourning. Full mourning for a woman was roughly 2 1/2 years minimum, or:

Full Mourning: 1st year after day of death plus one day;

Half Mourning: the next 9 months

Final: another consecutive 6 months flexible

Because there were so many deaths, and because the timeframes were so long, many women just wore mourning apparel the rest of their lives.

The stages of mourning were required to be “smooth transitions” one into the other. Subtle and small changes were made so there was no distinct separation. This was done through fabric, detail, design, accessories, and notions.

The exceptions to mourning were weddings and birthdays. For a few pleasant hours, women could drop the guise of mourning, and have some fun; but not too much. The other exception was during times of war, or if a husband had been away for very long times, the period could be shortened relative to how long he had been gone; typically the 2 1/2 years became 6 months after which time she could fully enter society and even get engaged again.

You Mourn – WE mourn

Typically when a member of a household went into mourning, and especially if it was the man of house or head of a household, EVERYONE went into mourning. This was a lifestyle as well as a manner of dressing and etiquette. Even pets were required to mourn, and superstition had people dressing their dogs, cats, and horses in purple or black ribbon so that the animals would not take “death and spread it outside the home”.

Babies were required to adhere to the rules, with appropriate garments and black armbands. Girls in particular were educated and trained using special manuals to and dolls to prepare them for the task ahead someday when they were women.

Households with servants almost always put their entire staff into mourning apparel and behavior. Visitors and calls were modulated, activity was subdued, and it was the House servants’ task to help the woman of the house maintain composure and decorum throughout the mourning period. When multiple family members died on top of their own families and friends, it meant domestics were often in “eternal mourning” too.

These Victorian dictates continued well into the 20th century until the death of Queen Victoria, when it seemed that under her son Edward’s rule, one could choose whether to follow the rules or not. At this time there was a rise in cremation and fast burials, but that was not long lasting. Many of the rituals remained until today. It was in about 1918 that some of the odd things were waived, such as the rules for fashion.

Mourning Stages

The rules and traditions of mourning were based upon signs, symbols, and visual messages that people had been told to associate with loss. The color black in particular was symbolic of “nothingness” and the striving for the “good death” that would end up with their own lives in heaven.

Full Mourning – “Widow’s Weeds”

This was the first year plus a day from the date of death of the loved one. These rules applied strictly to women, although men had a set of similar, but much less strict rules – and much shorter times.

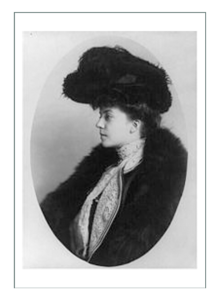

Year one was considered “deepest mourning” and the woman had to be completely covered in black. Each and every item of her ensemble from head to toe had to be black, and typically made of “crape”. Crape spelled this way was a specific type of silk fabric made for the mourning industry. One family built an empire off of manufacturing Crape in England. Even cuffs and pins and piping were black, and everything was piped. Crape covered ALL.

Other accepted fabrics were bombazine, paramatta, merino wool, and cashmere if crape was not available or feasible (such as in the cold north).

These were clothes specifically made and stored for this purpose. It was considered “gauch” to wear the same mourning clothes for a different death, but the cost of such was prohibitive, so some women stored them in special places and had them remade.

Mourning clothes were always in the same silhouette and style as the most current fashion. That’s how neighbors knew if they were being reused or not. Since not everyone could afford warehouses and tailors, many women simply dyed (died – haha!) their current fashionable clothes all black.

The problem with all the black fabrics was that dyes were not very stable yet. This meant if they got wet due to sweat or rain or anything, black would run down their arms and legs. For this reason, men were not required to wear full black, and shirts were only trimmed in black. This led to the armband. Women were not so lucky. They had to wear the black no matter what.

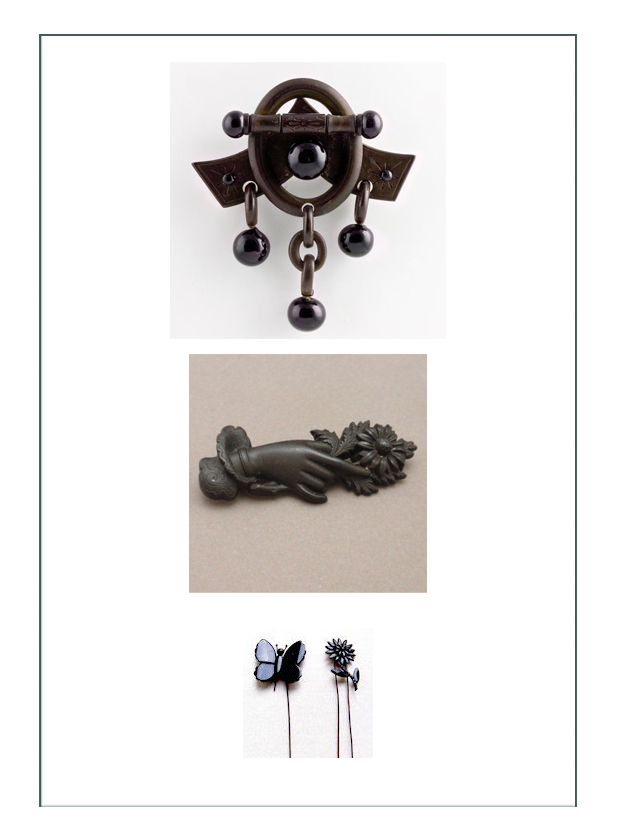

In year one, the only jewelry allowed was Jet.

The exception to all this black was if a young woman died, women could put a white hatband around their black hat.

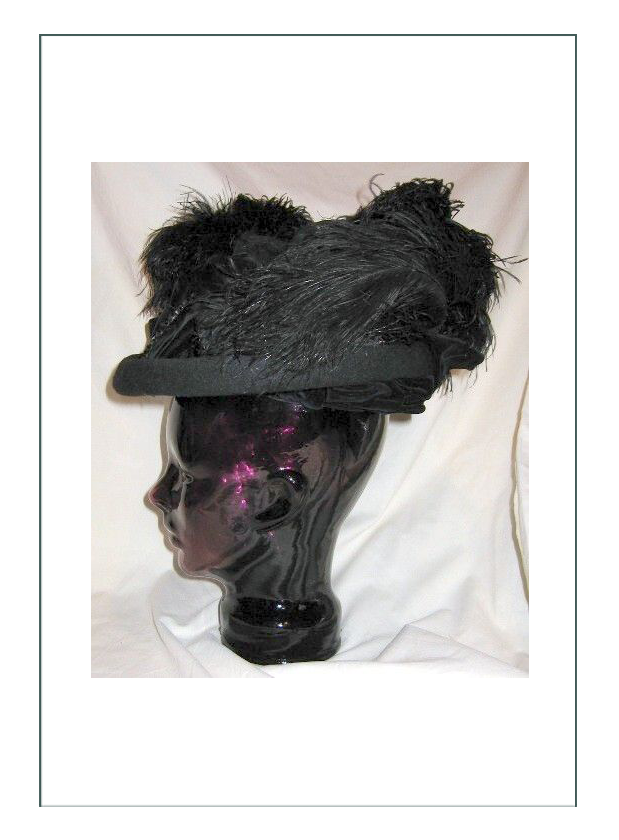

Half Mourning – Subtle transition

The next 9 months, if a woman was very sneaky and very careful, she could ease into different fabrics and notions and trims. Velvet and silk would be introduced as trim. Fringe or ribbon would be added, but still BLACK. Everything had to be black.

Last 6 months – color!

Nearing the end of the half mourning, subdued colors could be introduced – at first for trim and accessories; later as full dress colors. Accepted were subdued shades of gray, white, purple, violet, pansy, heliotrope, mauve, and of course more black. They would start by adding just a hint of color such as a rose on a hat in mauve, or a rosette in white on the bodice. As they moved through the transition, they had purple and cream ornament, pretty belts, streams, jet buttons, and purple armbands.

Armbands were favorites for women, men, and children. They were especially favored in courts and with nobility, because it seemed in royal families someone was always dying, and they would be in eternal black because of their many connections. The Royals did not strictly adhere to the rules for that reason, but depended on the bands, streamers, and accessories.

Rules the same no matter dress, hat, shoe, or hair(pin)

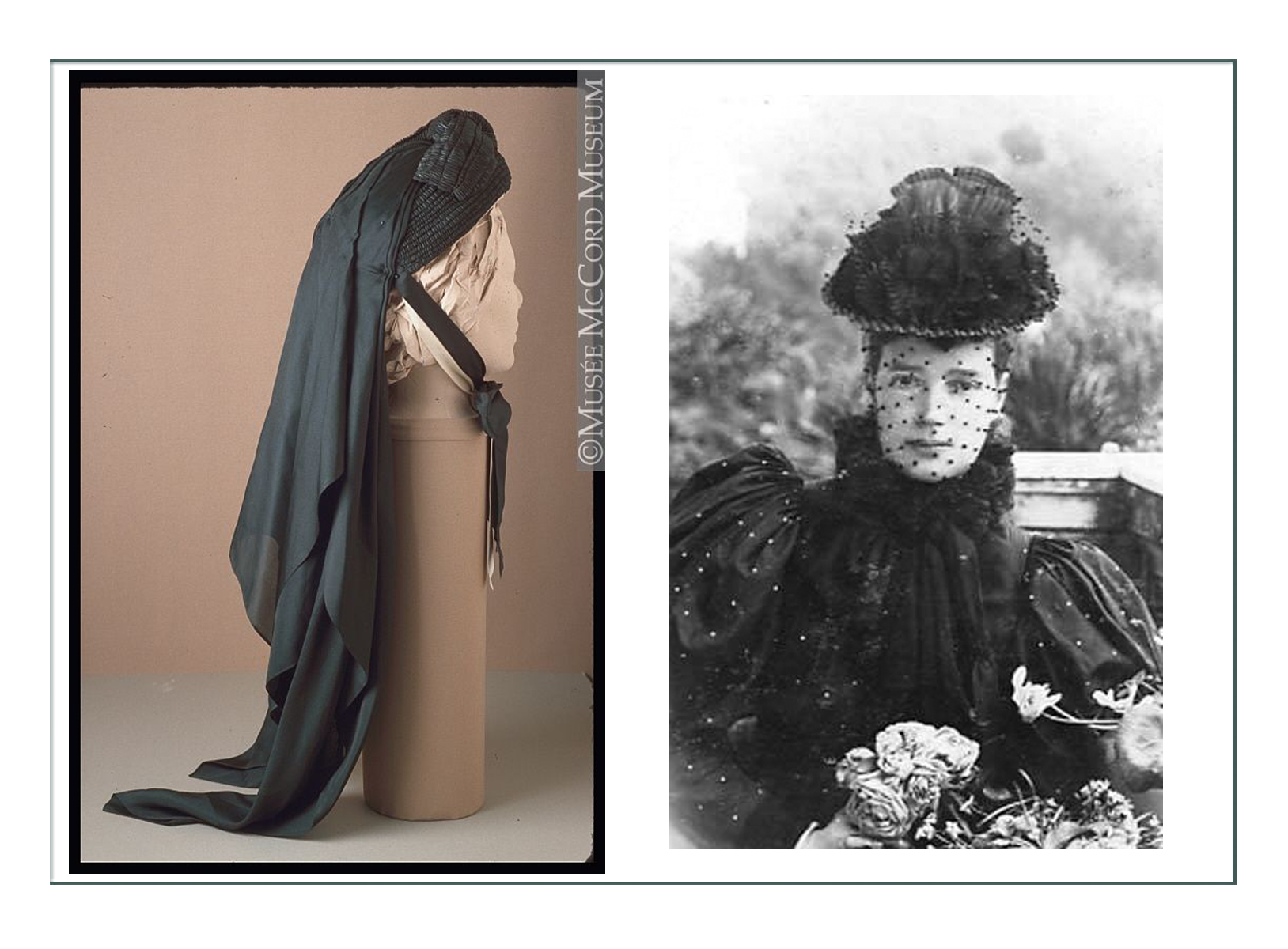

Hats and bonnets followed the same rules: all black and crape at first, and then gradual transition to fabrics and colors. It was still considered “gross” to suddenly pop out with color and texture after 2 1/2 years, so the transition to everyday clothes could take up to years afterwards. Hats would start with full face covering veils, and then gradually after 3 months into full mourning, the veil would move to the back of the head and eventually disappear.

Jewelry was Jet (a fossiled tree found in some parts of England; or a pressed glass from France) at first, and then was gutta percha, bakelite, or resin through the transitions. Jet was such a huge industry that many examples can be found today of mourning jewelry.

Jewelry was Jet (a fossiled tree found in some parts of England; or a pressed glass from France) at first, and then was gutta percha, bakelite, or resin through the transitions. Jet was such a huge industry that many examples can be found today of mourning jewelry.

The Georgians and Regency era mourners were a big macabre, and it was expressed significantly in their death jewelry which depicted skulls, masks, graves, grave digging tools, and symbols of evil death. Their theory was “Remember you too will die”.

The Victorians with their concept of “We will all die someday, so let’s work at getting into heaven” focused on clouds and angels and happy thoughts of heaven. They practiced “Lost but Not Forgotten” in their imagery and rituals. They were marking the passage of life, and keeping their loved ones close in an “outward display of loss”.

Jewelry was most particular in symbolizing this concept. It was almost always black to symbolize the loss of light and life.

#1 Acceptable and the only thing allowed in full mourning was Jet. Jet is fossilized tree (some say coal).

#2 Vulcanite and gutta percha (remember they did not have plastics yet, although bakelite was being used for jewelry and resins in cameos which were predecessors of today’s plastics)

#3 forms of rubber from trees of SE Asia

#4 onyx, black enamel, tortoise shell, and French Jet (which was glass)

Children and unmarried women could wear white jewelry.

The big thing, especially for lower classes because it was affordable, was hair of the loved one. Woven, framed, braided, or just stuck into a locket, it was all the rage.

Depictions and miniature paintings on lockets of clouds, weeping willows, tombs, urns, angles, women lamenting at tombs, etc. were favorites to be painted on the outsides of lockets while keeping a photo of the deceased loved one on the back or inside.

Etc.

Gloves were acceptable, and even white in the Half Mourning stage, as long as they were embroidered with black threads. Hair brooches – lockets and pins and little framed pictures made from the hair of the deceased were absolute favorites. Many women made them of their own hair or that of their children before their deaths to leave for their loved ones.

When a household went into mourning, so did the servants. It was easy for most of the women domestics; they were already in all black. The difference between the high fashion and fashionable women in mourning and the servants was in the quality, cut, and amount of fabric, notion, trim, and detail of the ensemble.

Since Maid garments were styled according fashion of the day, they could be elaborate or plain depending on their employers. It is most likely they wore their work clothes when working – which were basically already mourning type sedate and non colorful gowns. While some servants (and nurses) wore light colors, prints, and textures, most did not.

It is debatable whether servants wore mourning clothes for their employers when off the job, but because most housemaids and domestics lived on the premises, they would be required to have some semblance of mourning; at least armbands like the pets to keep the spread of death from passing outside the door.

It is known when a servant was required to have a new mourning ensemble made, it was trimmed with crape, and having a muslin collar and cuffs. They would also have a black silk, although very simply designed bonnet or hat, black silk handkerchief, black stockings, and black gloves. The dress itself would be of bombazine or a cheaper fabric of a less full cut than fashionable counterparts.

A maid would have one ensemble for dressing up, and 2 plain gowns for work. It would be rare to have a new ensemble made for a death in the family.

Extant Garments, Real Women, and Advertisements of 1902

Hats

Click here to go to Design Development Page (next)

Click here to go to the Main Page to see the Finished Project