“Age of Expansion”

Expansion of ideas, inventions, & dresses

—— THE ERA IN BRIEF ——

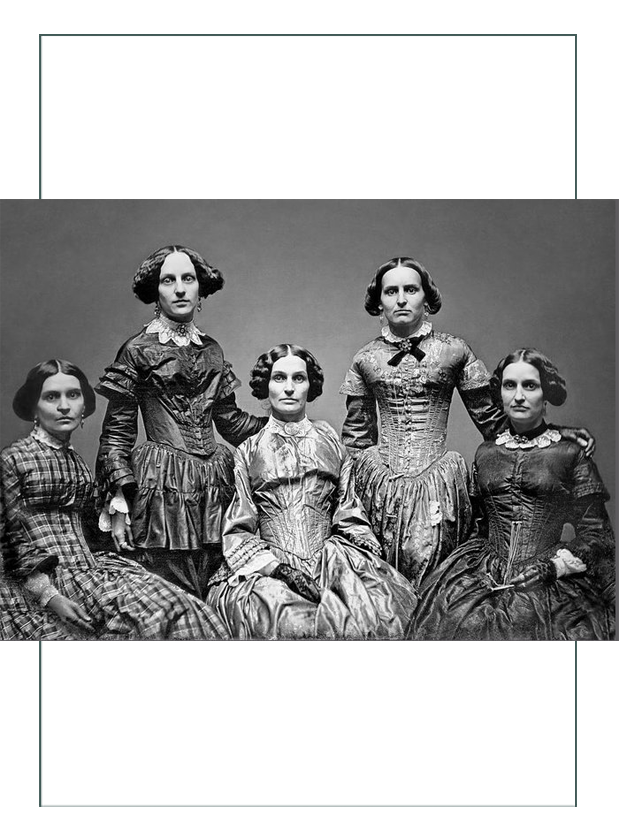

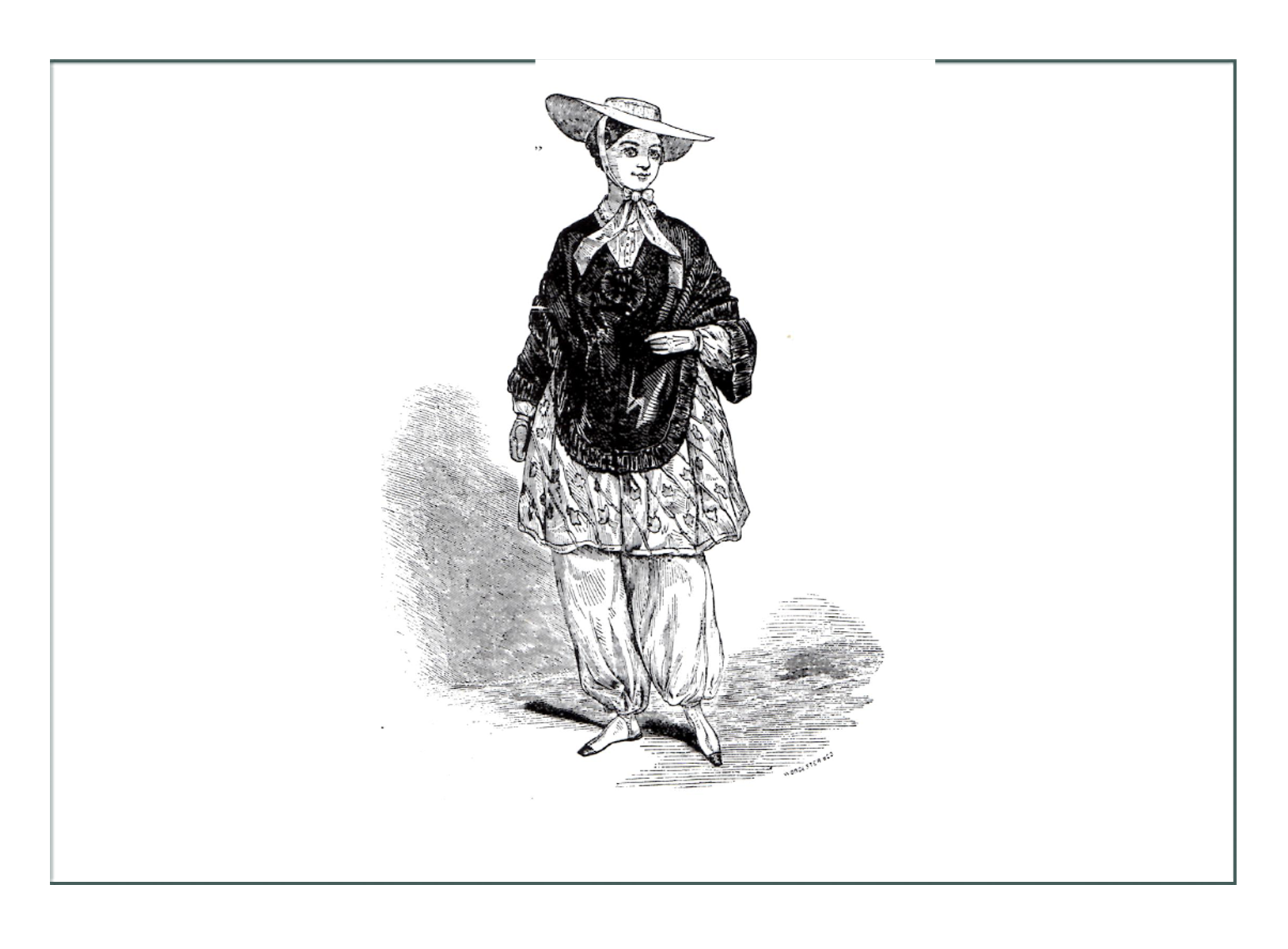

Society in American & Europe were prospering with the development of great ideas like indoor plumbing & the shopping mall. With the invention of the crinoline hoop skirt & metal grommets, women made themselves into “Belles” literally & figuratively, following the lead of a tiny-waisted 18 year old Queen Victoria of England who had just taken the throne. At the same time “49’ers” were panning for gold in California, Charles Worth was inventing a “costume” for every event, while paisley was up & bloomers were down in popularity.

—— WORLD SITUATION ——

- Queen Victoria came to the throne in 1837 at the age of 18, & would dominate history & world fashion until the next century

- Victoria’s rigid disciplinary standards for 64 years set the “Victorian Eras”

- Under Victoria’s rules, it was improper to even say the world “legs”, let alone look at them under a woman’s garments during this era

- Everything Victoria did was to spur the English economy

- Countries worldwide flourished with improvements on steam engines in all industries & science

- Indoor plumbing, gas lighting, & fast transport changed lives & status of all classes & peoples

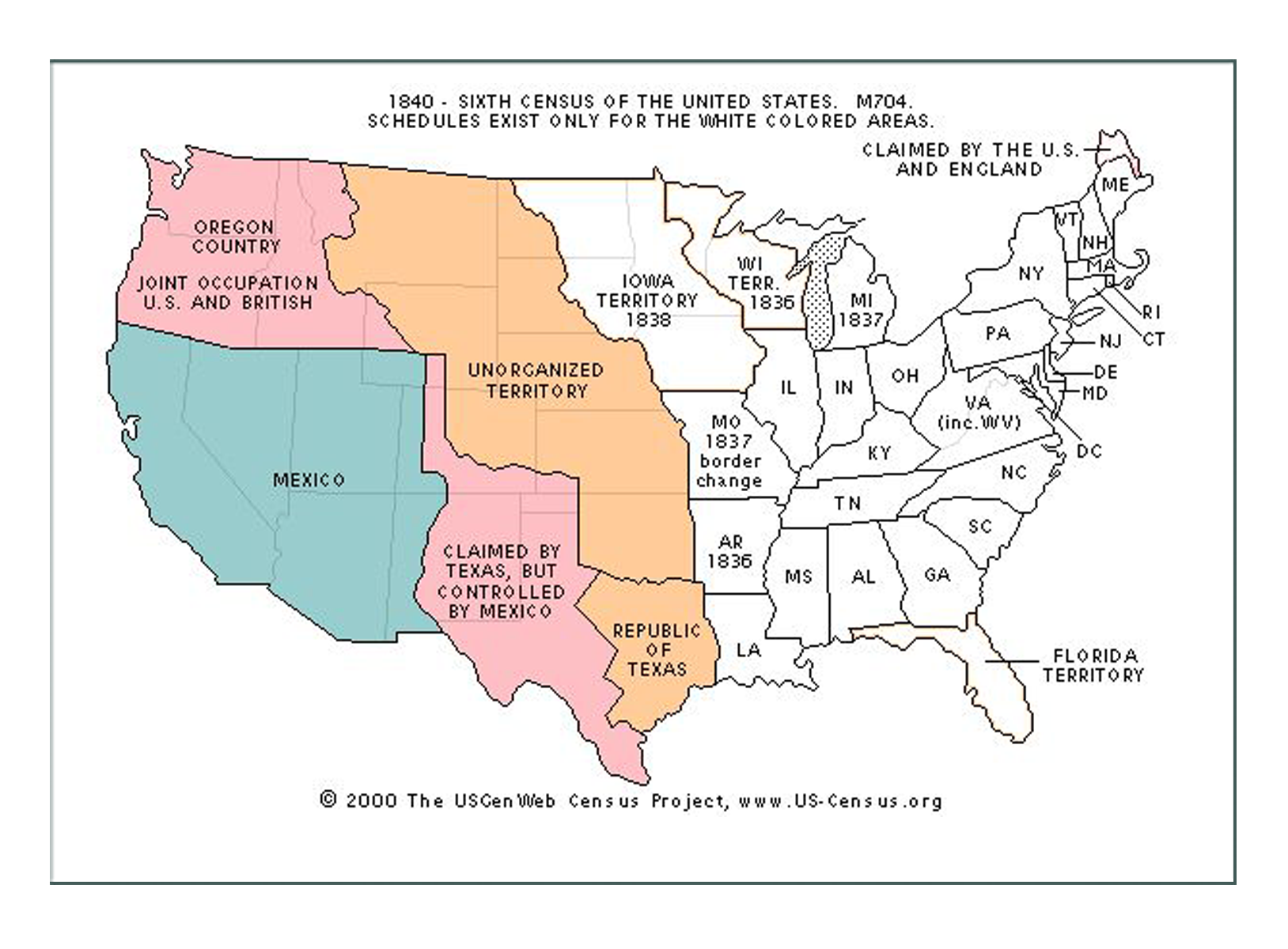

- America acquired Nevada, New Mexico, & California in 1848 in a treaty with Mexico

- There was another Revolution in France in 1848, which cut off communication & trade from that country & others

- Gold was discovered in California, starting the gold rush & western expansion in the US

- America went to war with Mexico 1846-48, ending with Mexico ceding large territories to America

- Literature such as “Moby Dick” & “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” expressed ideas of pre-Civil War in America

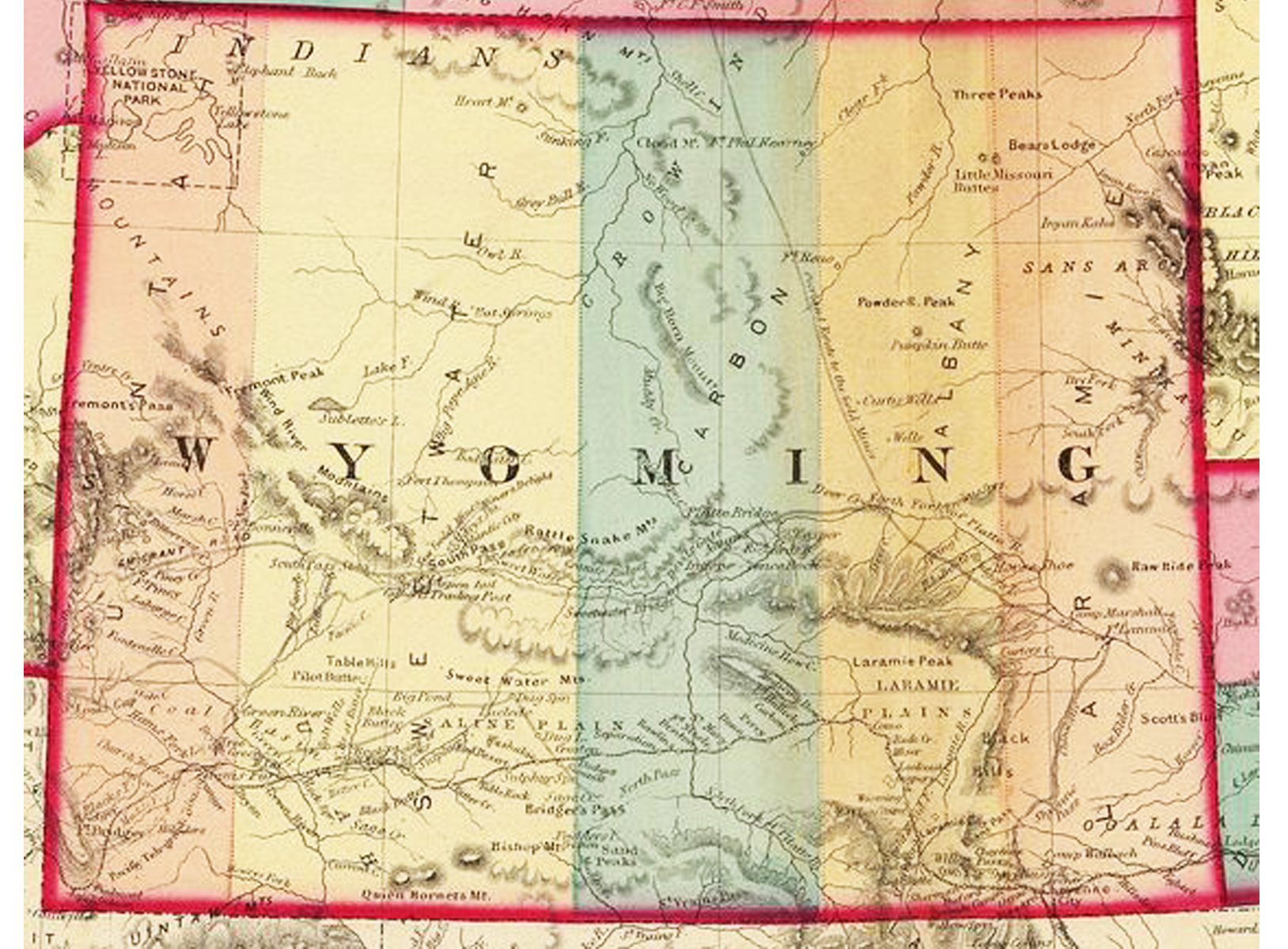

Lander, Wyoming

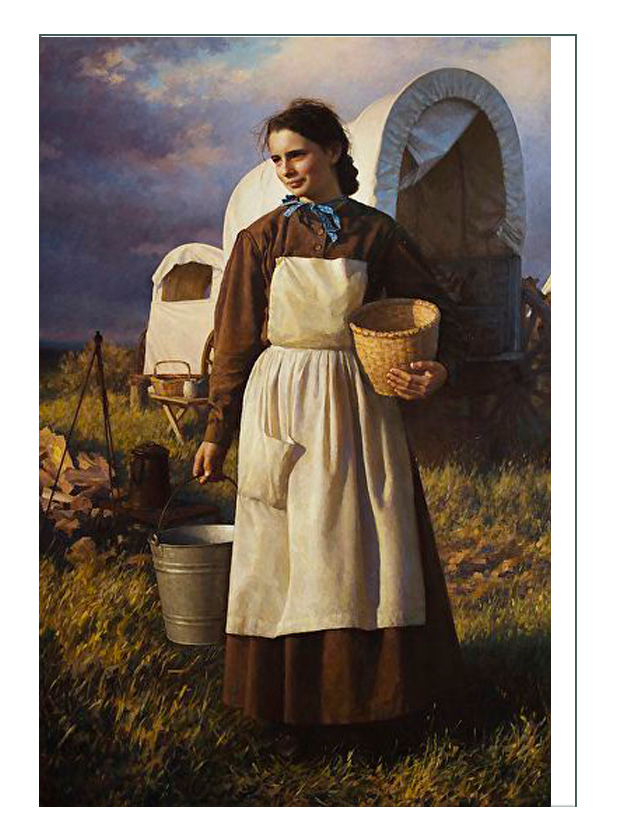

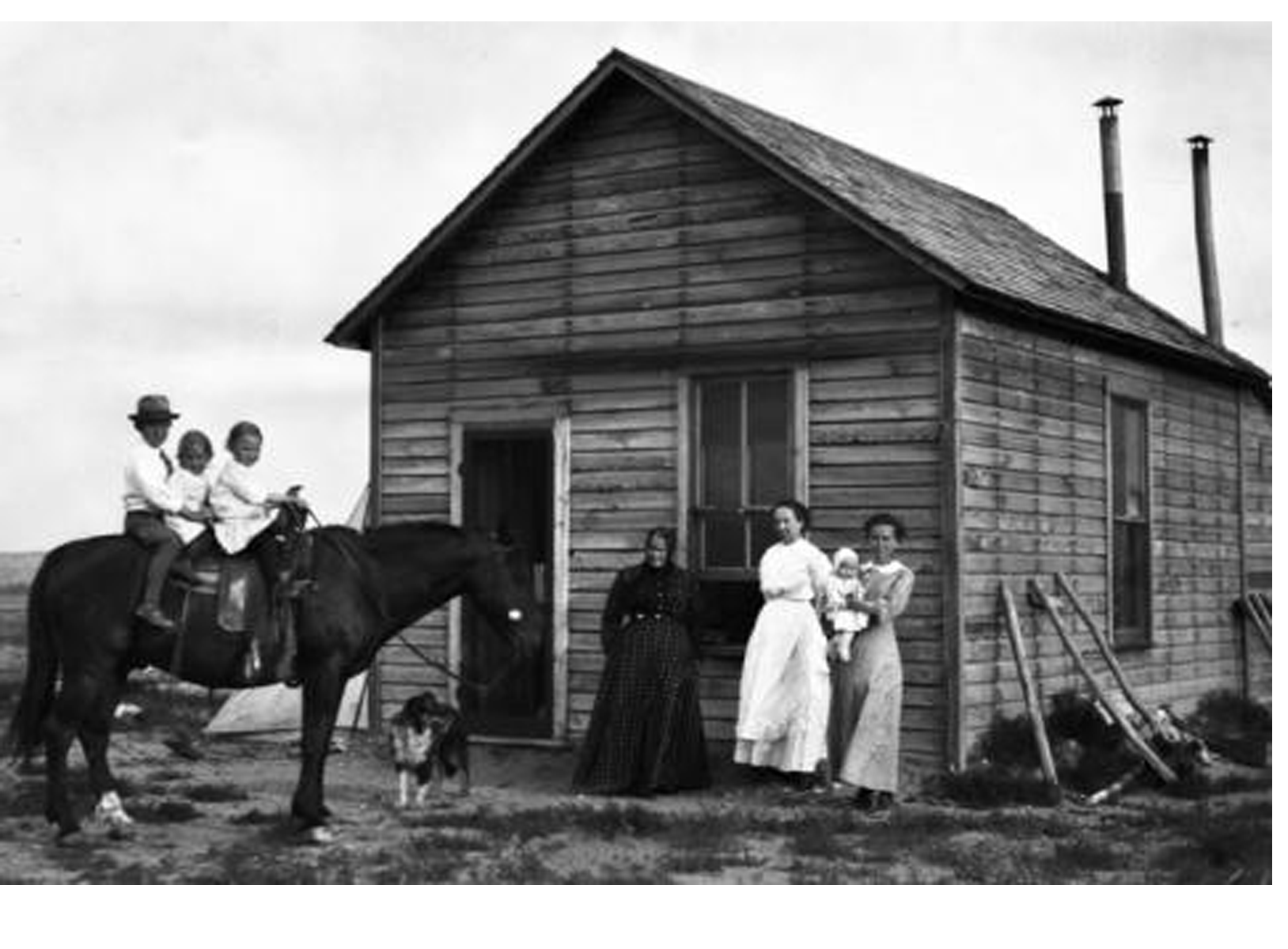

Jessica’s character is placed in the current Lander, Wyoming region in the time frame 1845-1855. She would like to wear her ensemble to participate in current activities and events, and to honor the history of the region. She is a rancher, and would prefer to depict the same, but this real history indicates that would not be what a woman was doing in the mid-19th century.

From Wikipedia:

The Region

Europeans may have ventured into the northern sections of the state of Wyoming in the middle of the 19th century. Most of the southern part of modern-day Wyoming was nominally claimed by Spain and Mexico until the 1830s, but they had no physical presence.

John Colter, a member of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, was probably the first Anglo-American to enter the region in 1807.[8] His reports of thermal activity in the Yellowstone area were considered at the time to be fictional. Robert Stuart and a party of five men returning from Astoria, Oregon discovered South Pass in 1812. The route was later followed by the Oregon Trail.

In 1850, Jim Bridger located what is now known as Bridger Pass, which was later used by both the Union Pacific Railroad in 1868, and in the 20th century by Interstate 80. Bridger also explored the Yellowstone region and like Colter, most of his reports on that region of the state were considered at the time to be tall tales.

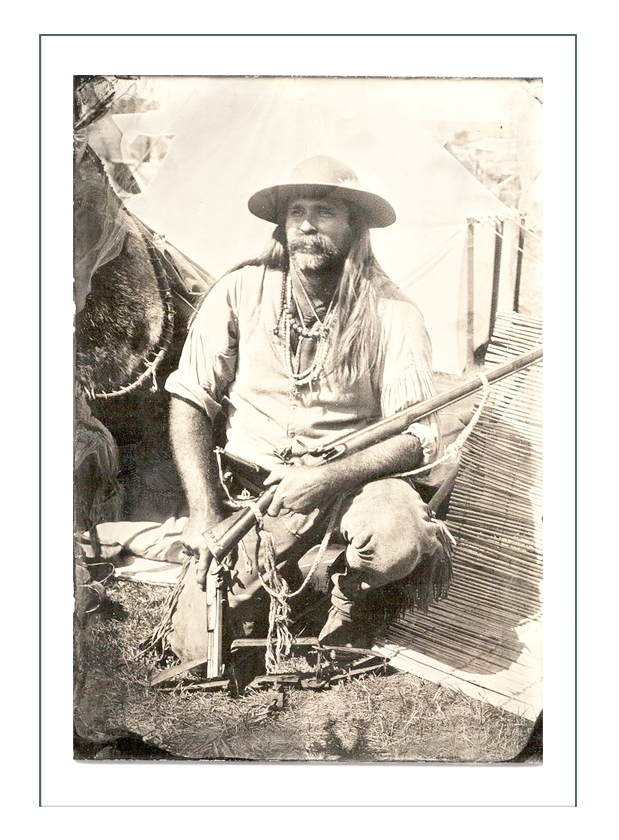

During the early 19th century, fur trappers known as mountain men flocked to the mountains of western Wyoming in search of beaver. In 1824, the first mountain man rendezvous was held in Wyoming. The gatherings continued annually until 1840, with the majority of them held within Wyoming territory.

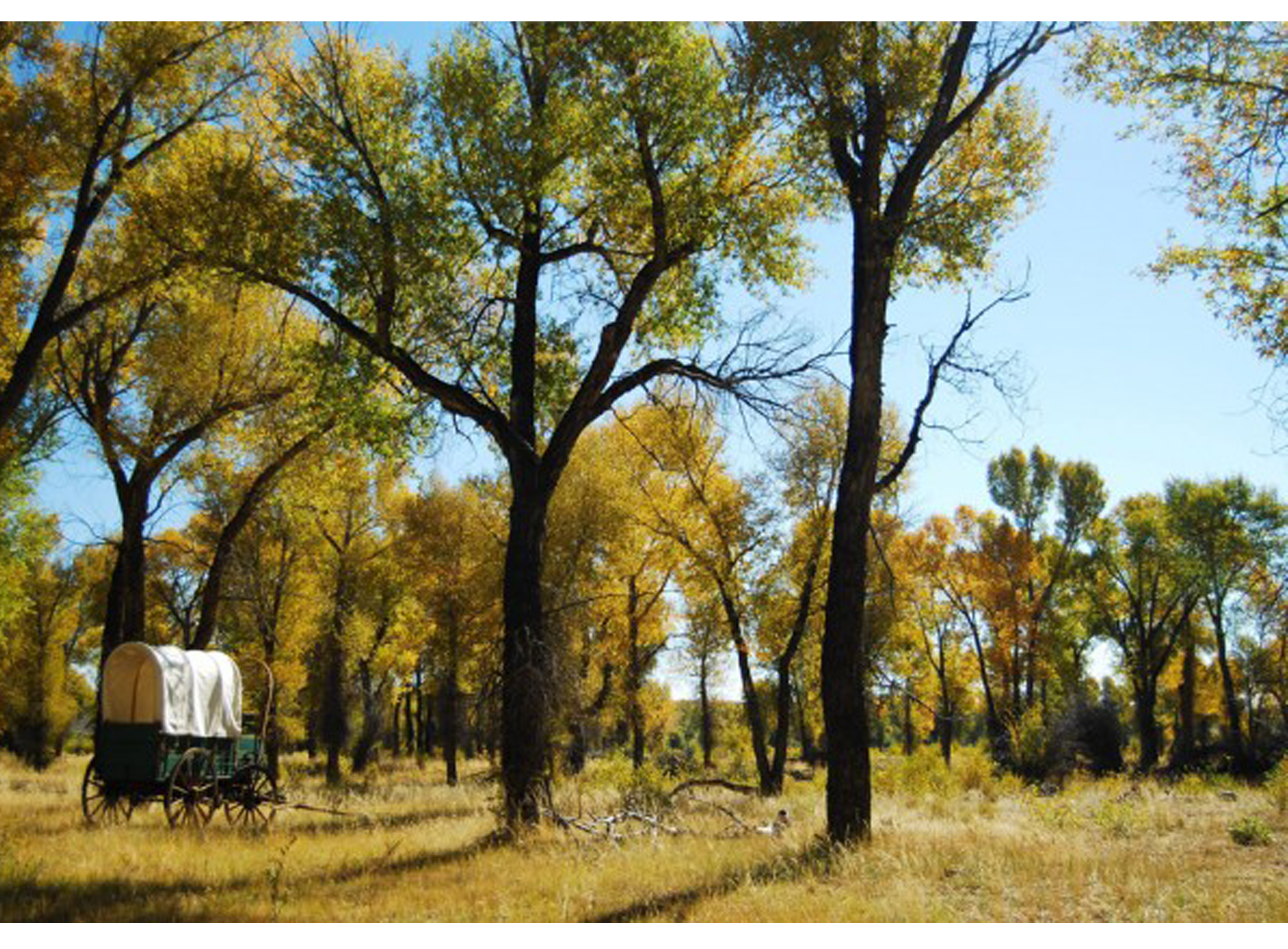

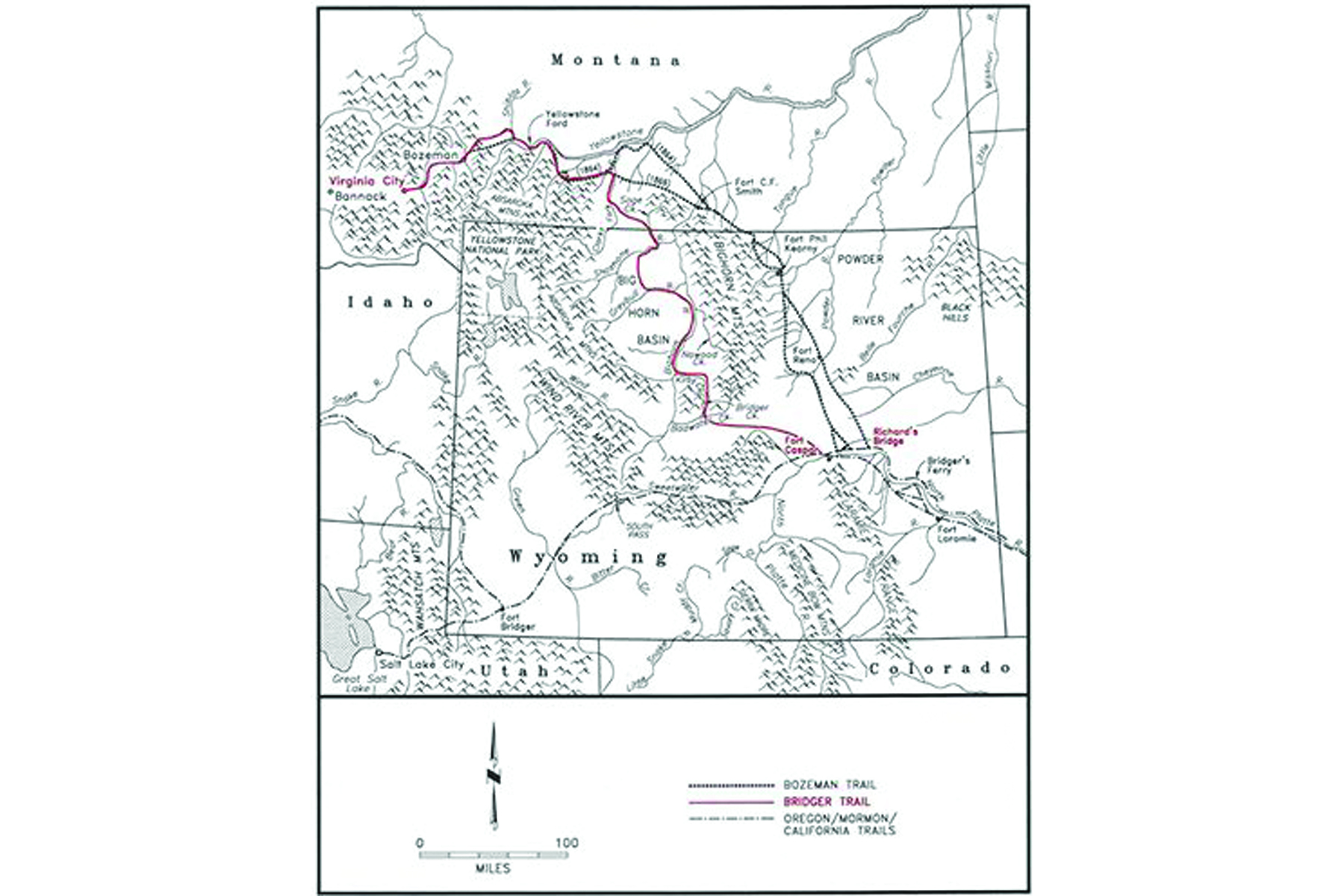

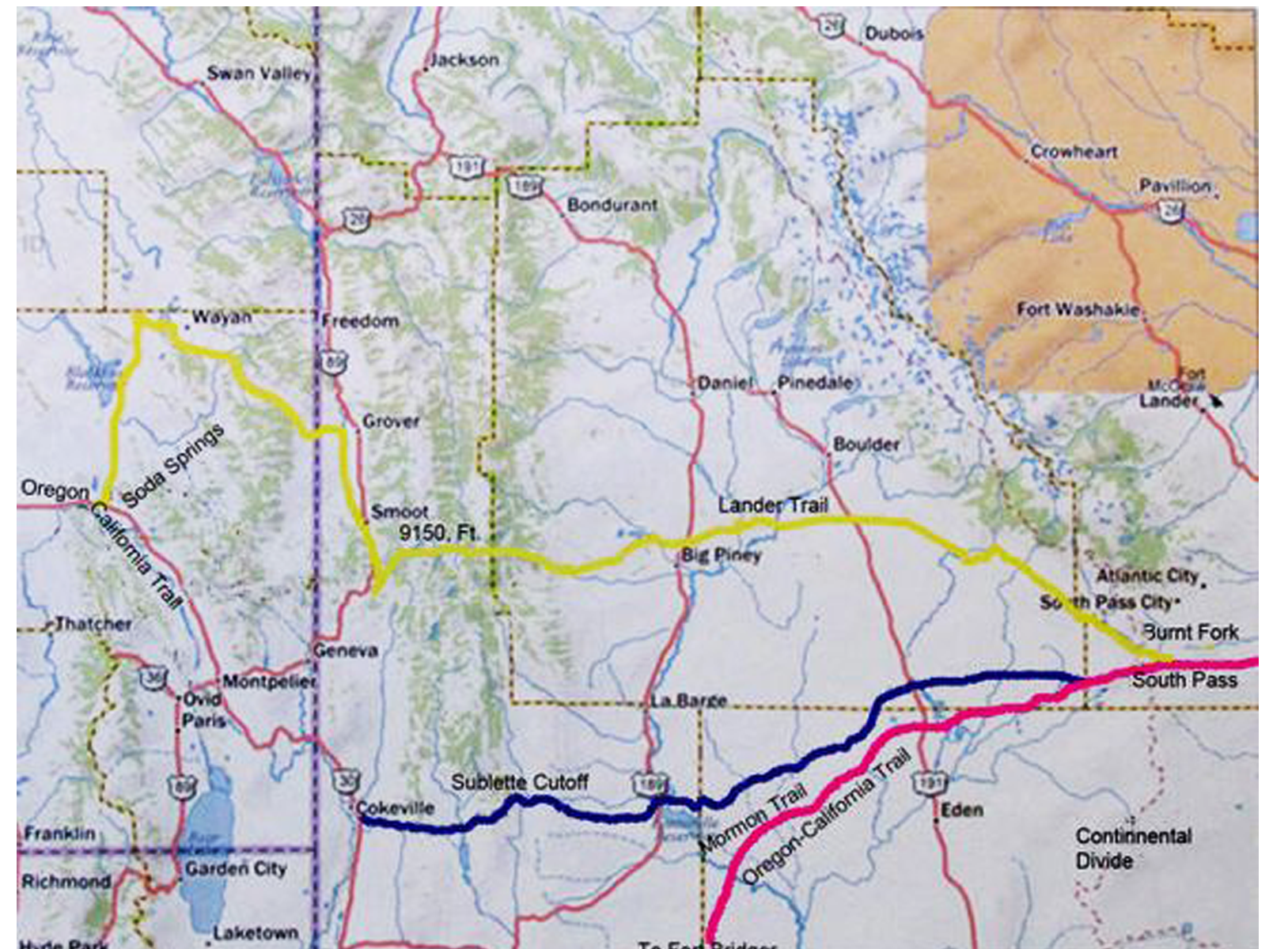

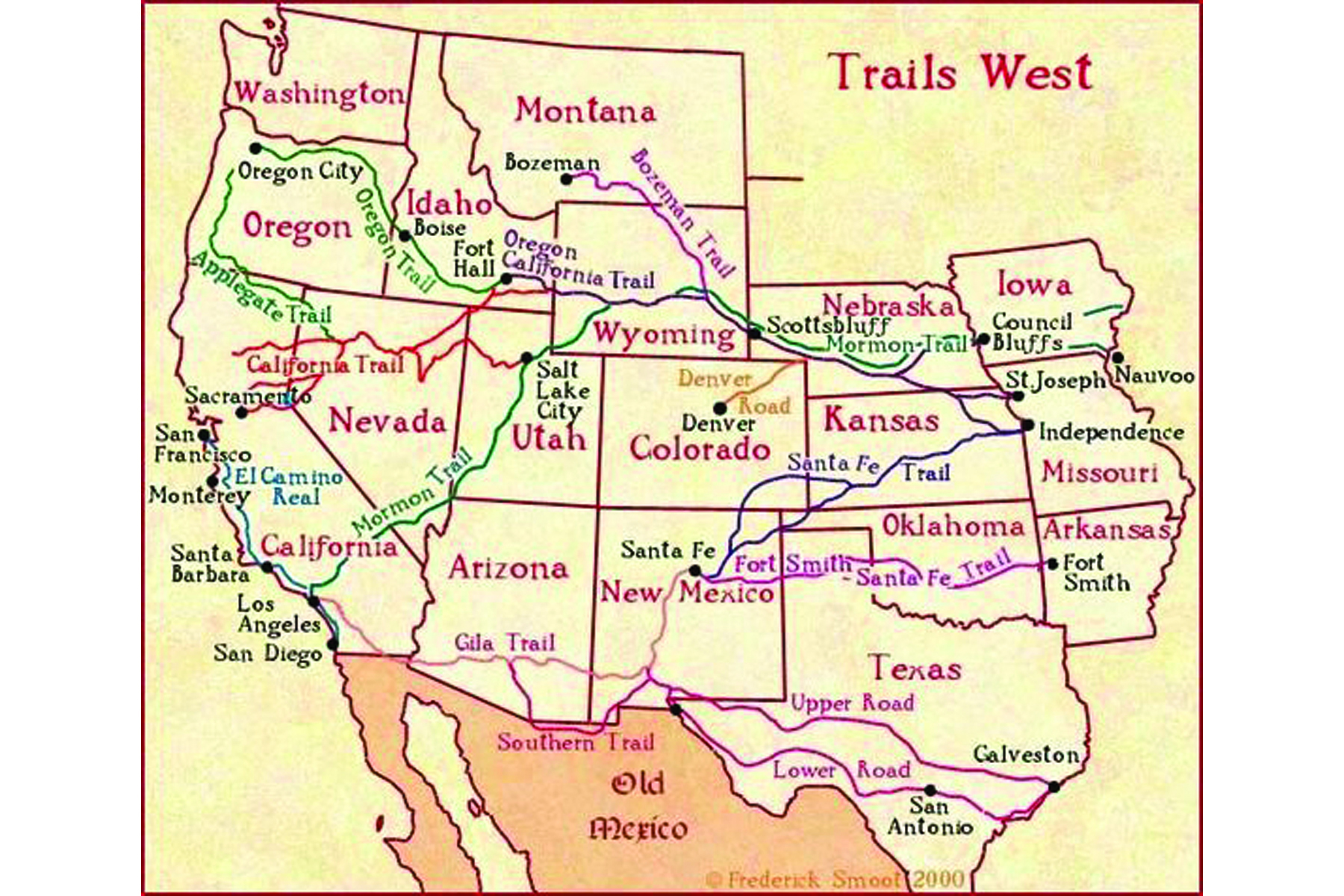

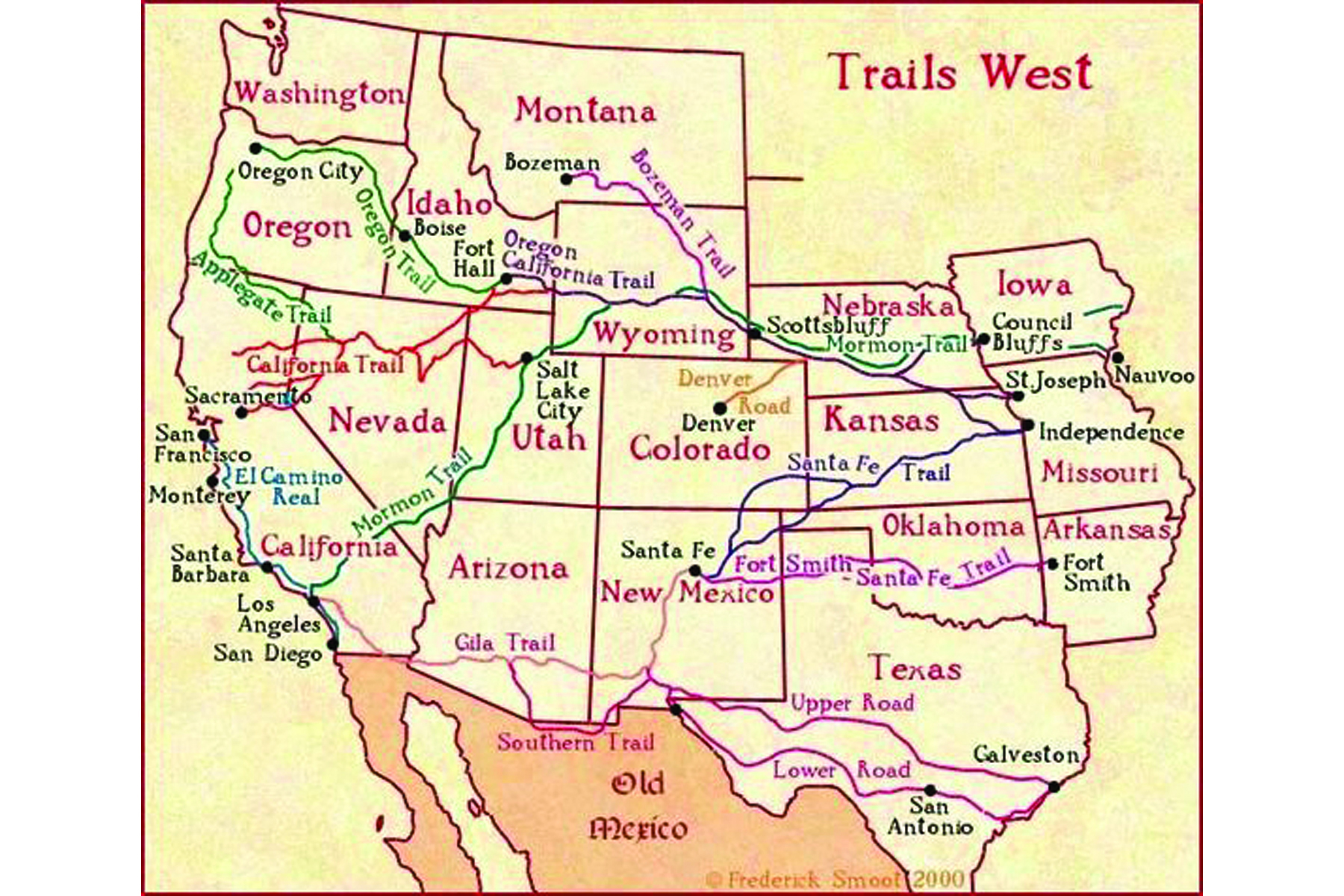

The route later known as the Oregon Trail was already in regular use by traders and explorers in the early 1830s. The Oregon trail snakes across Wyoming, entering the state on the eastern border near the present day town of Torrington following the North Platte River to the current town of Casper. It then crosses South Pass, and exits on the western side of the state near Cokeville.

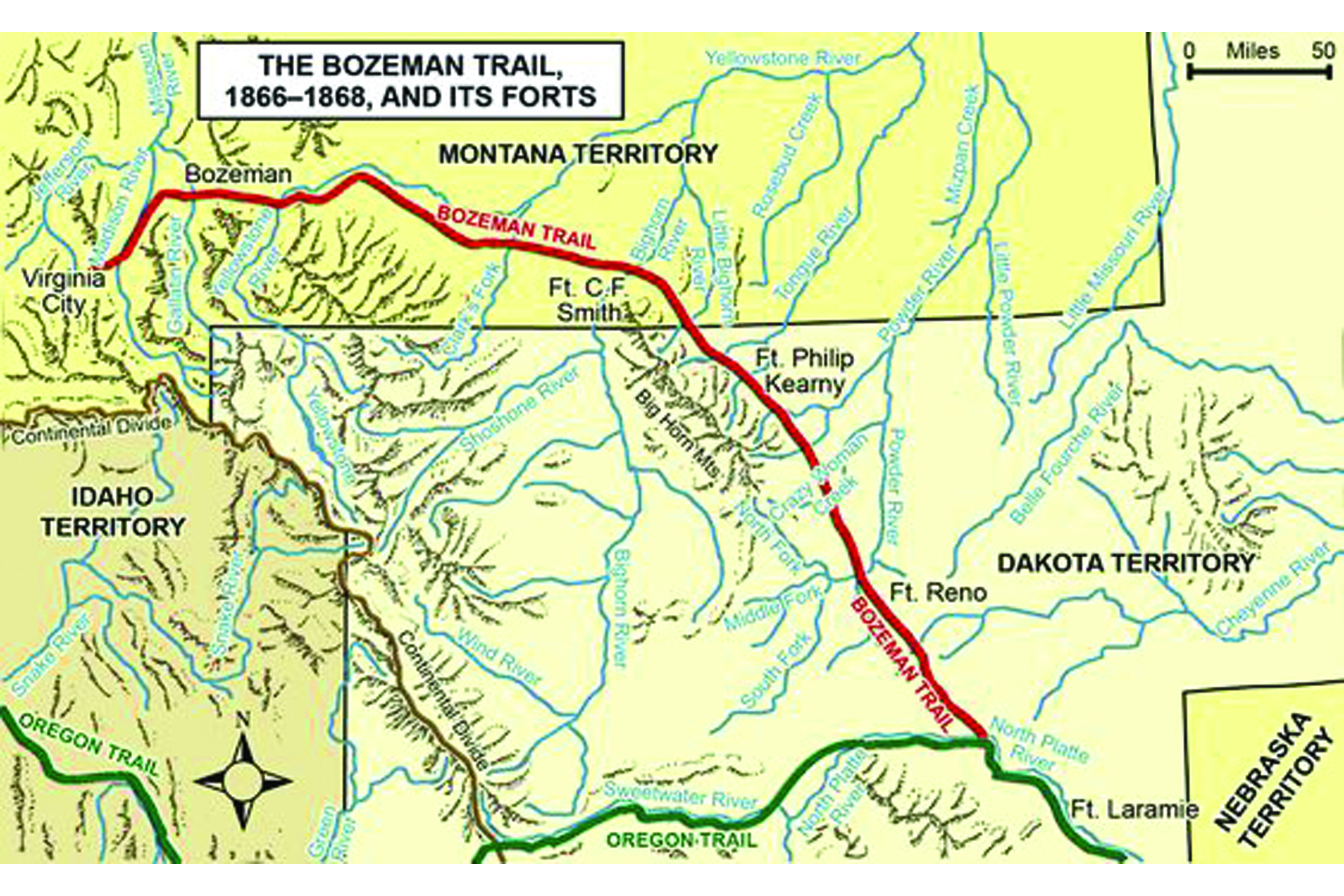

In 1847, Mormon emigrants blazed the Mormon Trail, which mirrors the Oregon Trail, but splits off at South Pass and continues south to Fort Bridger and into Utah. Over 350,000 emigrants followed these trails to destinations in Utah, California and Oregon between 1840 and 1859. In 1859, gold was discovered in Montana, drawing miners north along the Bozeman and Bridger trails through the Powder River Country and Big Horn Basin respectively.

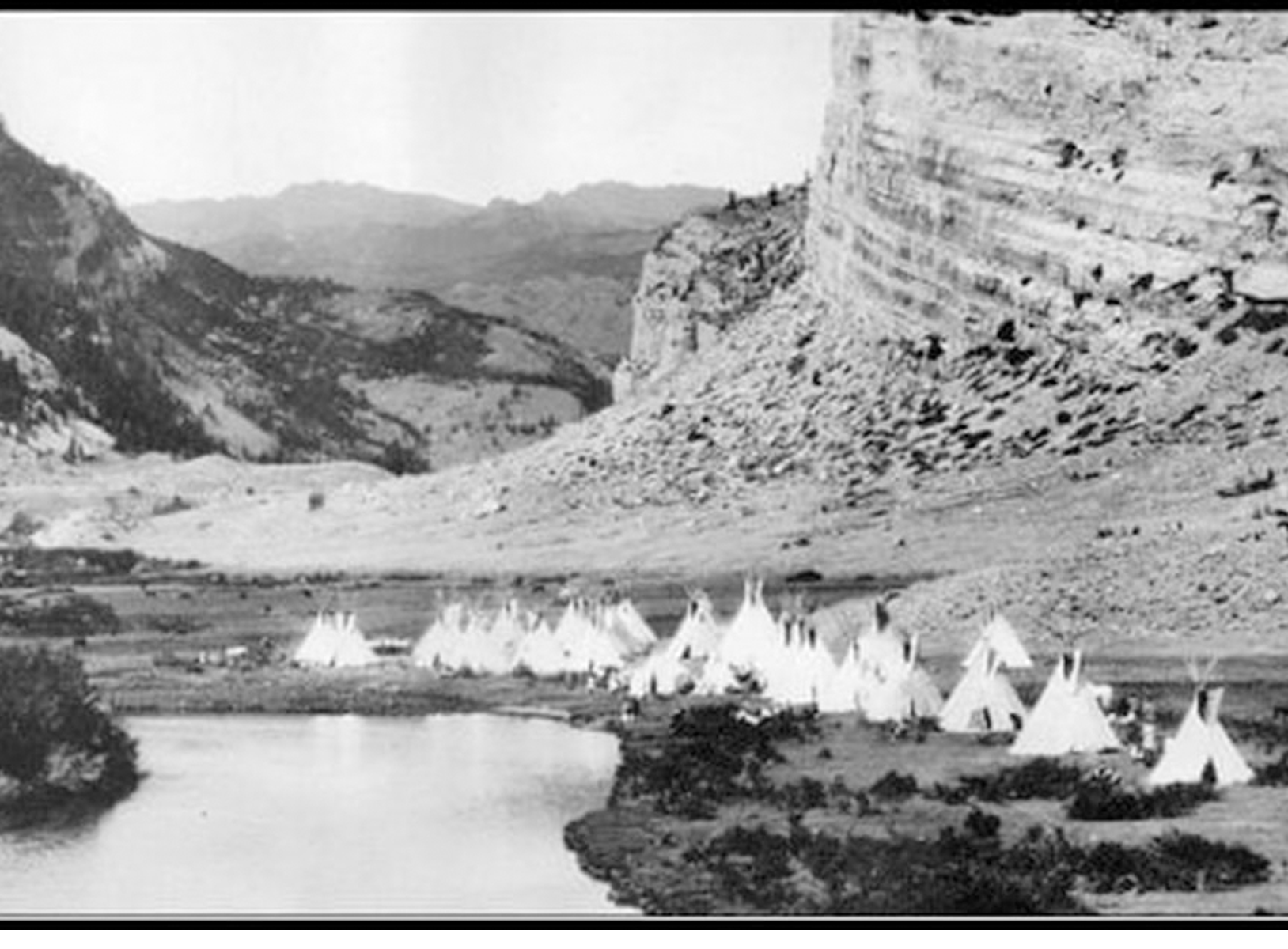

The influx of emigrants and settlers into the state led to more encounters with the American Indian, resulting in an increase of military presence along the trails. Military posts such as Fort Laramie were established to maintain order in the area. In 1851, the first Treaty of Fort Laramie was signed between the United States and representatives of American Indian nations to ensure peace and the safety of settlers on the trails. The 1850s were subsequently quiet, but increased settler encroachment into lands promised to the tribes in the region caused tensions to rise again, especially after the Bozeman Trail was blazed in 1864 through the hunting grounds of the Powder River Country, which had been promised to the tribes in the 1851 treaty.

As encounters between settlers and Indians grew more serious in 1865, Major General Grenville M. Dodge ordered the first Powder River Expedition to attempt to quell the violence. The expedition ended in a battle against the Arapaho in the Battle of the Tongue River. The next year the fighting escalated into Red Cloud’s War which was the first major military conflict between the United States and the Wyoming Indian tribes. The second Treaty of Fort Laramie in 1868 ended the war by closing the Powder River Country to whites. Violation of this treaty by miners in the Black Hills lead to the Black Hills War in 1876, which was fought mainly along the border of Wyoming and Montana.

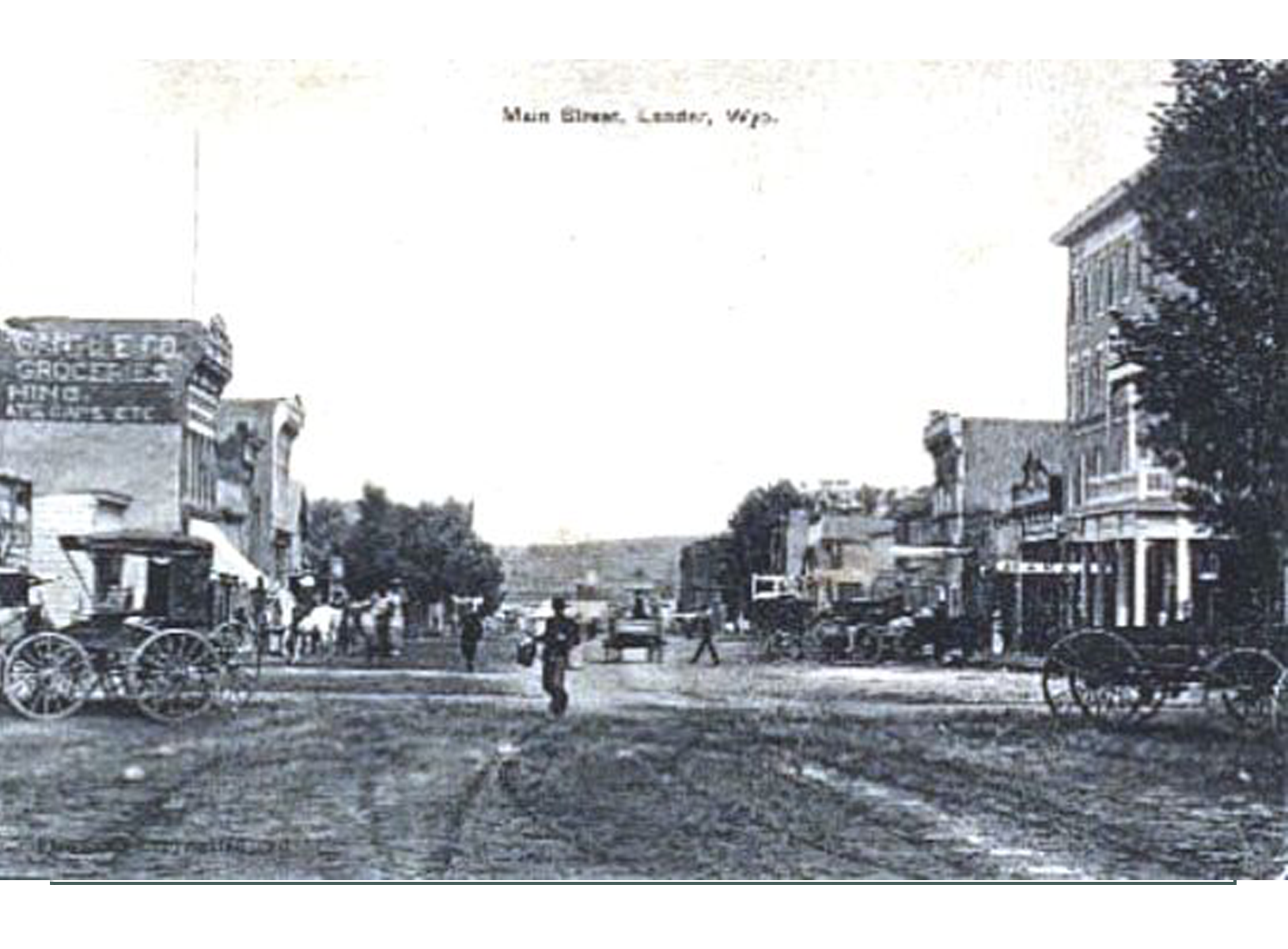

Lander Specific

Lander is a city in Wyoming, United States, and the county seat of Fremont County. Named for transcontinental explorer Frederick W. Lander,[7] Lander is located in central Wyoming, along the Middle Fork of the Popo Agie River. A tourism center with several guest ranches nearby, Lander is located just south of the Wind River Indian Reservation. The population was 7,487 at the 2010 census.

Lander was known as Pushroot, Old Camp Brown,[8] and Fort Augur prior to its current name. The name Lander was chosen in 1875 in reference to General Frederick W. Lander, a transcontinental explorer who surveyed the Oregon Trail’s Lander Cutoff.[9]

The City of Lander has played a major role in the settlement and development of west-central Wyoming since the late 1860s. It is associated with several major frontier themes: the Great 19th Century Westward Migration, due to its close proximity to the Oregon Trail; military explorations and Indian relations in the formation of the Lander Cut-Off in 1859, and the Wind River Indian Reservation in 1868.

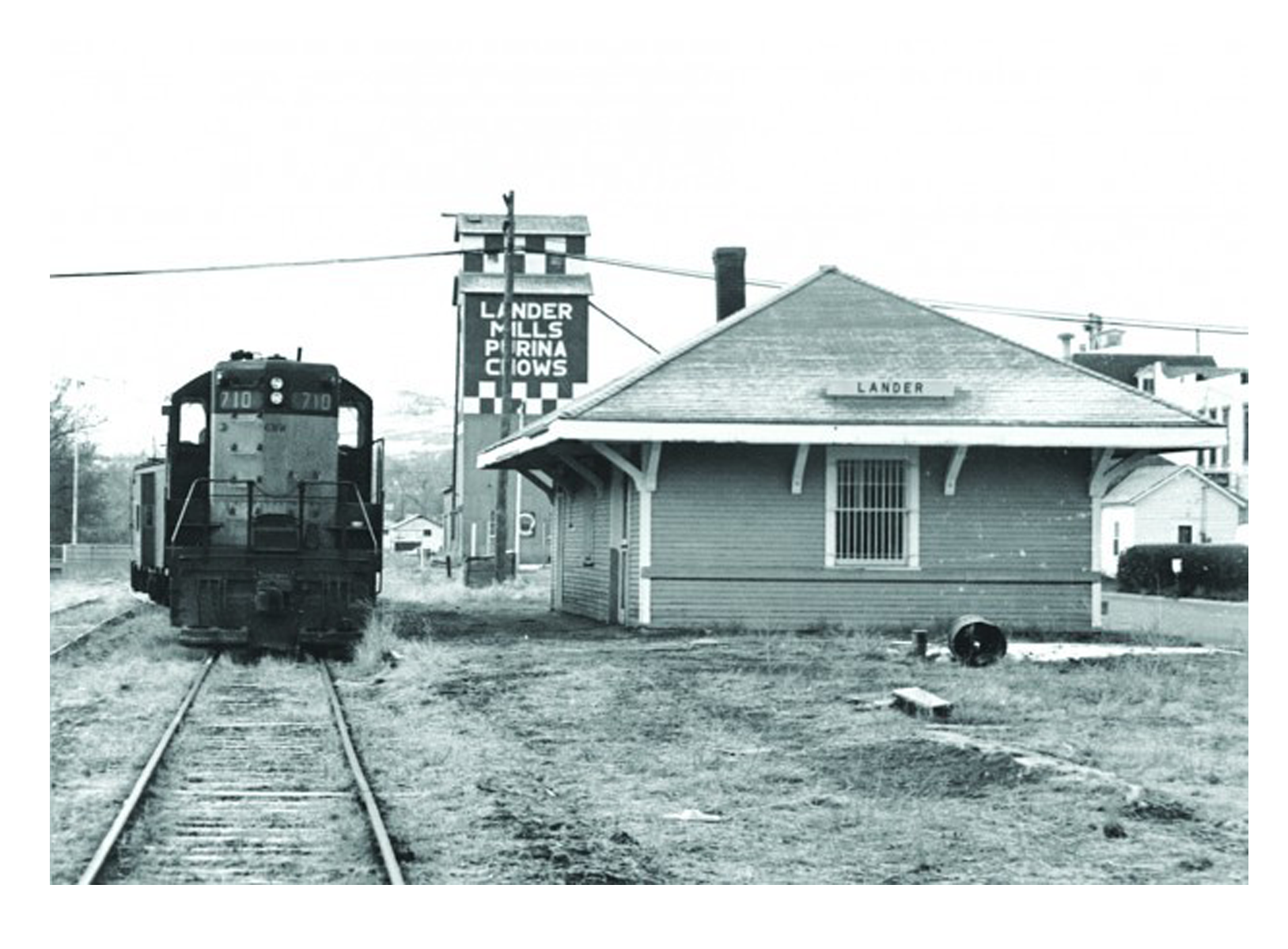

It also was instrumental in the nearby South Pass mining boom, the establishment of major transportation and communication routes to serve the Wind River Reservation, the arrival of the railroad in 1906, cattle and sheep ranching; the early 20th century oil industry, and Lander‘s development into a major commercial center in the Lander Valley. Euro-American settlement had begun in the Lander Valley shortly after the discovery and development of significant gold deposits in the South Pass area in 1867.

The townsite was part of the Wind River Indian Reservation under the Fort Bridger Treaty of 1868 which set the reservation border near the Sweetwater River.[10] By the early 1870s, however, rising tensions between white settlers illegally living on the reservation, the Shoshone and other tribes were resulting in isolated conflicts.[10][11]

The U.S. Government had also learned most of the desirable land east of the Wind River Mountains was on the reservation.[10] As a result, in 1872 Congress authorized a delegation to meet with the elders of the Shoshone, including Chief Washakie to negotiate the trade or purchase of lands south of the North Fork of the Popo Agie River.[10] After several meetings at Camp Stambaugh in the summer of 1872, the Shoshone agreed to sell the southern part of the reservation to the U.S. for $25,000, $5,000 in stock cattle and a five-year annual salary of $500 to Chief Washakie.[10]

The next year in 1873 The Jones Expedition further explored and documented the area that would eventually become Lander while finding a route to Yellowstone National Park.[12] The expedition documents everything from hot springs to oil reserves and hieroglyphs in the area.[12] Several miles southeast of town near present-day U.S. Route 287 is Dallas Dome, the site of Wyoming’s first oil well completed in 1883.[13] The town was incorporated on July 17, 1890.[14]

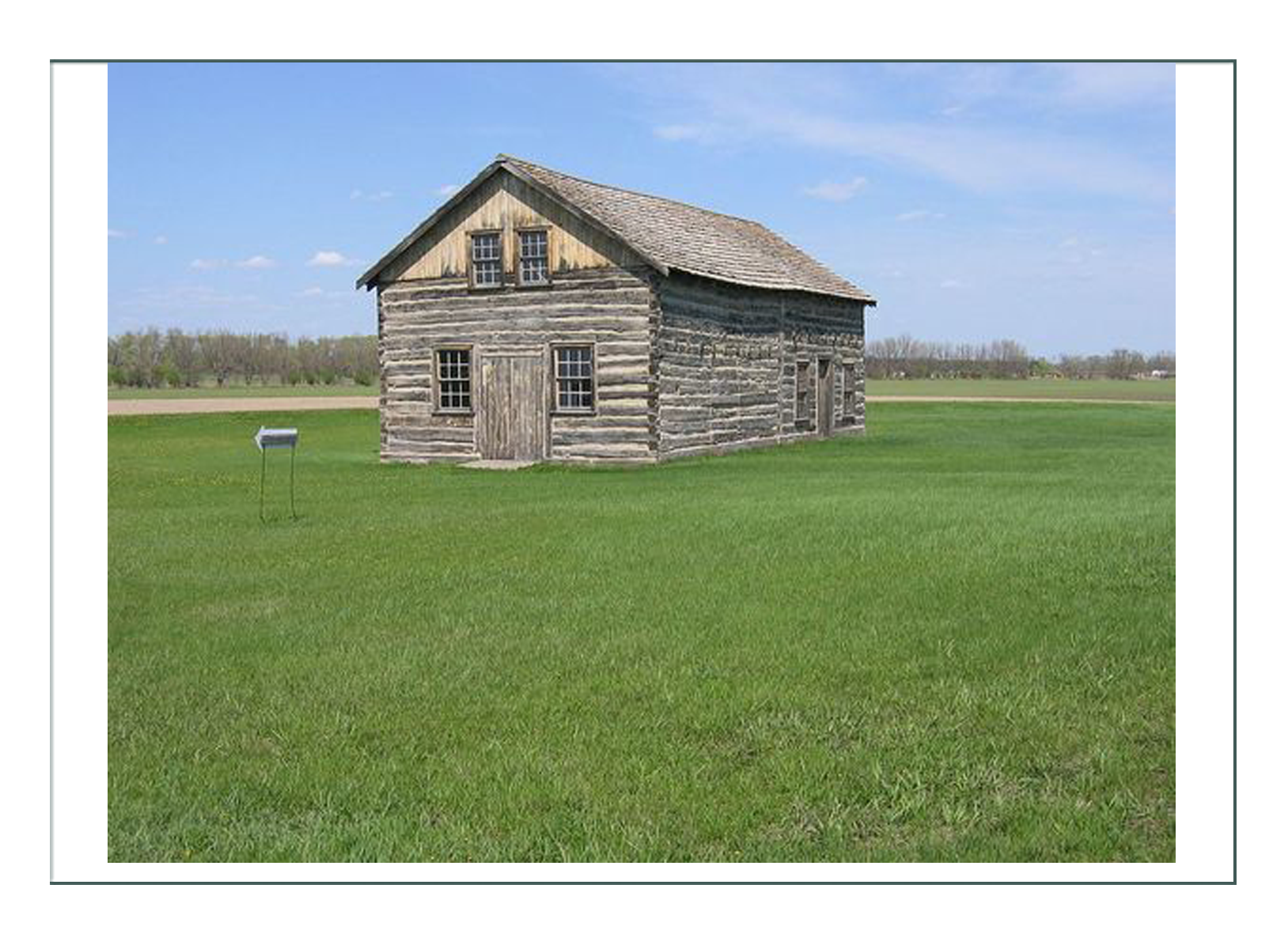

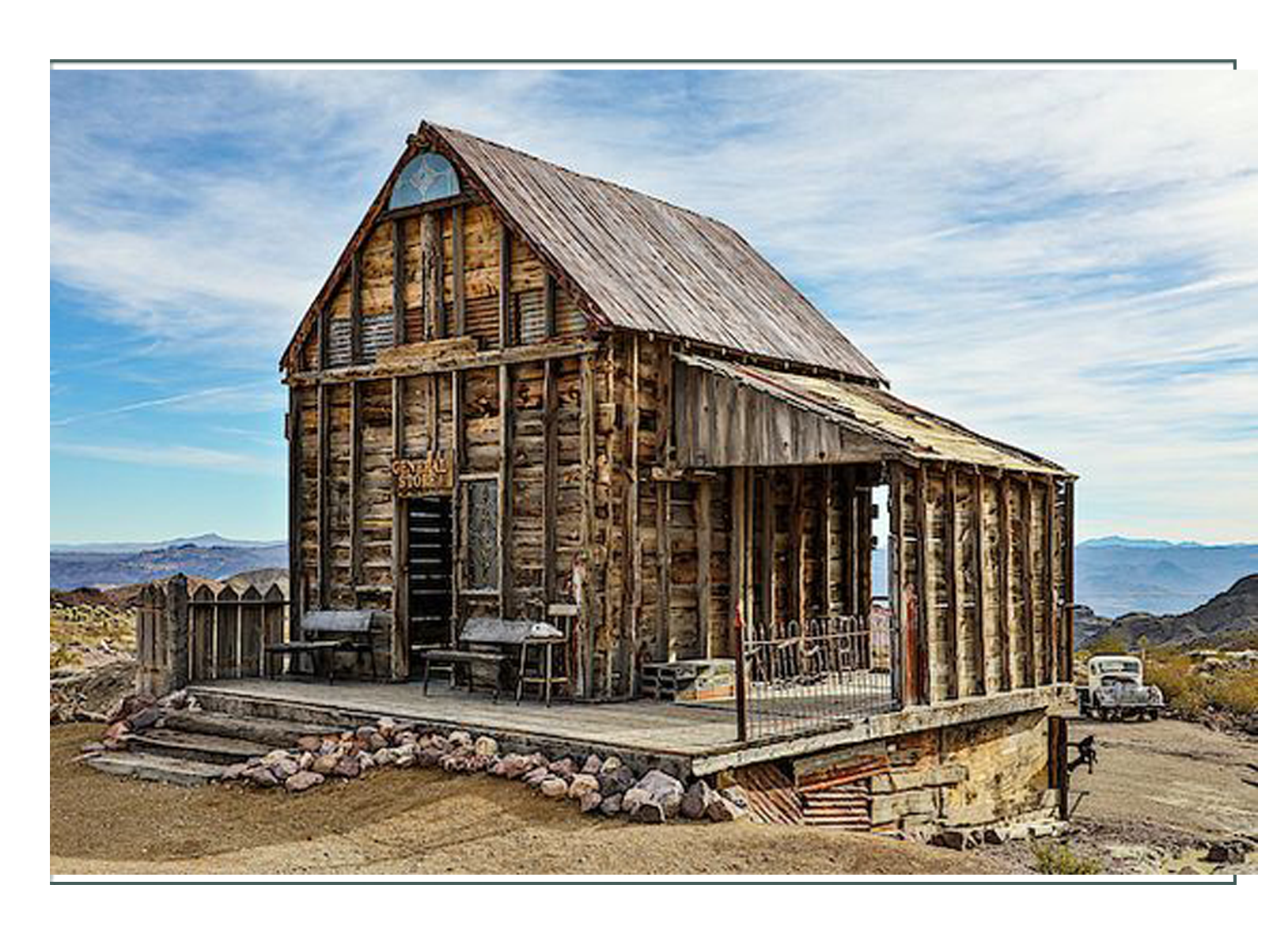

The Lander commercial district grew from a post office and several businesses established as early as 1875. The district experienced several major building booms, progressing from log and wood frame buildings to more substantial two-story brick and stone masonry edifices with highly ornamental facades. The majority of the remaining commercial buildings within the district date from the late 1880s-early 1890s boom. Despite subsequent boom and bust periods brought on by the wildly fluctuating energy and ranching industries, Lander has endured as a stable commercial and social center for the Lander Valley.

Twentieth century Lander

On October 1, 1906, Lander became the westward terminus of the “Cowboy Line” of the Chicago and North Western Railway, thus originating the slogan “where rails end and trails begin.” Originally intended to be a transcontinental mainline to Coos Bay, Oregon, or Eureka, California, the line never went further west, and service to Lander was abandoned in 1972.[15] With the arrival of the railroad, Lander’s population more than doubled between 1900 and 1910.[16] At the turn of the century the town and surrounding valley were promising places for agricultural development due to the area’s climate and potential for irrigation.[17] At the time there were several new ventures around the town producing wool, wheat, oats, alfalfa, hay, vegetables, small fruit and in some cases orchards.[17] However, a report from the State of Wyoming published in 1907 says agriculture around Lander only supplies local demand.[17] In 1962 U.S. Steel opened the Atlantic City iron ore and mill, 35 miles south of Lander near Atlantic City[18] The mine was a significant employer in Lander, but by 1983 it ceased operations.[18]

Twenty First Century Lander

Lander continues to evolve and faces similar issues as many small towns in the Western U.S. Education and outdoor recreation play a large role in the town’s economy with the Wyoming Catholic College and National Outdoor Leadership School both based in Lander. Though agriculture and resource extraction no longer play a large role in the town’s economy, its population has continued to grow since the year 2000.[19][20]

Lander’s economy is based on an array of industries and like Wyoming as a whole is supported by substantial tourism.[21] Outdoor recreation along with healthcare, education, construction and retail sales make up much of the economy.[19] The tourism season is primarily during summer months and though Lander and Fremont County are not near any major Interstate highway, the county generates significant income from travel related taxes.[22]

Present day Lander is home to numerous state and federal government offices, including the U.S. Forest Service (Washakie Ranger District, Shoshone National Forest),[23] the Bureau of Land Management (Lander Field Office),[24] the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service,[25] and a Resident Agency of the Denver Field Office of the FBI, as well as the Wyoming Life Resource Center[26] and the Wyoming Department of Environmental Quality.[27] A major bronze foundry, Eagle Bronze, is located in Lander,[28] as is the headquarters of the National Outdoor Leadership School (NOLS) [29] and other environment and land-related non profit organizations including offices of the Wyoming Outdoor Council, the Wyoming office of The Nature Conservancy, the Wyoming Wildlife Federation, and Wyoming Catholic College.

- The Pioneer Days Parade and Rodeo takes place on July 3 and 4 every year.

- Lander’s Fourth of July Parade in 1962.

- The Lander Brew Festival features samples from Rocky Mountain-area breweries and has been held since 2002.[33]

- Lander is also home to the Wyoming State Winter Fair.[34] In addition to Livestock showings, there are also plenty of rodeo activities to see or participate in.

- Other annual events include the International Climbers Festival, and the Annual One Shot Antelope Hunt.[35]

Lander Attractions

- Lander Flour Mill From http://millhouselander.com/our-story.html

The Lander flour mill was built in the year 1888 by Eugene Amoretti. The mill was the first big step towards the town becoming self-sufficient. Before it was opened, it took two weeks to get a shipment of flour from the nearby town of Rawlins. For years, this iconic building functioned as Lander’s only flour mill, producing enough flour for the whole town.

The mill was first run using a water wheel, but in 1890 it switched to electricity. Because the mill was only operational during the day, the excess electricity that was produced during the off hours was not being used, and thus the mill allowed the Lander, Wyoming to use the excess electricity. This simple act led to a small, western town to being one of the first to have electricity within the United States.

The mill remained operational until the late 1950’s. It is now a boutique hotel where Jessica works!

2. Museum of the Mountain Man

From https://museumofthemountainman.com/

As the oldest Historical Society in the State of Wyoming, the Sublette County Historical Society was originally established in 1935 for the preservation of historic sites of the fur trade and rendezvous, marking of settler graves and trails and to collect all records, documents and items pertaining to the historical background of Sublette County. Today’s SCHS is the parent organization for the Museum of the Mountain Man.

The facility presents a visual and interpretive experience into the era of the mountain man, the Plains Indian, the Oregon Trail and the developments of this region. It sponsors programs, living history events and workshops for both children and adults to further explore Wyoming settlement history. It produces the annual Green River Rendezvous Commemoration Days. A research library is available by appointment for public use.

The Museum of the Mountain Man is operated by the Historical Society in a public-private partnership with Sublette County. The Museum of the Mountain Man was opened in 1990 in Pinedale. The Historical Society holds over 15,000 artifacts ranging from pre-historic to the settlement era.

Approximately one-half of the Historical Society’s yearly budget is from private funds and one-half is public funds, via the Sublette County Museum Board. This unique 50-year-old partnership is a commitment by local government and private citizens to work together for local history. Sublette County’s community heritage is preserved and interpreted by a private foundation that can raise private funds to maximize the power of the public funds.

Founding members of the Historical Society began the modern-day rendezvous reenactment program in 1936 in Daniel, to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the 1836 rendezvous, which was attended by the first white women to cross the Continental Divide. The Rendezvous Pageant is still performed every year in July by the Green River Rendezvous Pageant Association during Rendezvous Days in Pinedale.

Artifacts directly traceable to the mountain man are extremely rare. The Museum’s collection has many period-correct pieces from the fur-trade era, but few directly attributable to the mountain men. Genuine artifacts in the Museum’s collection include a rifle owned by Jim Bridger after the fur trade era and archaeological pieces from the site of Fort Bonneville. Sublette County’s acquisition of the fur-trade papers significantly expands the Museum’s genuine artifact collection and ability to interpret the Rocky Mountain fur-trade era.

Our mountain man heritage is the kinship we have to those adventurous young men who chose this remote and harsh environment to make a living, much like those of us who live here today. We have a multi-generational history of embracing and celebrating the men who opened the West and expanded a country.

more from Wikipedia:

3. City Park Lander City Park located on the south end of town provides camping space and hosts a number of events in summer.

4. Outdoor attractions near Lander include Sinks Canyon State Park, Worthen Meadow Reservoir, Shoshone National Forest, the Wind River Mountains, and the Red Desert. Additionally, Lander is home to a number of museums,[36] including the Fremont County Pioneer Museum, which focuses on the history of the Lander area; the Museum of the American West, which maintains a complex of historic structures; the Sacagawea Cemetery, the cemetery is located near Fort Washakie, 15 miles north of Lander on the Wind River Indian Reservation; the Lander Children’s Museum, with hands-on exhibits; and the Evans Dahl Memorial Museum, dedicated to the Annual One Shot Antelope Hunt.[37]

5. Notable Lander people

- Clayton Danks, the model of the cowboy on the Wyoming state trademark, the Bucking Horse and Rider, is interred at Mount Hope Cemetery in Lander.[47]

- Larry LaRose, NASA flight engineer, shuttle training aircraft, shuttle carrier associate, is a native of Lander.

- Nate Marquardt, a mixed martial artist and current welterweight in the UFC, was born in Lander.

- Joseph B. Meyer, Wyoming attorney general and state treasurer was an assistant county attorney in Lander early in his political career.

- Bob Nicholas, Wyoming State representative from District 8 in Cheyenne, is a native of Lander.

- Sacagawea, from the Lemhi Shoshone tribe assisted Lewis and Clark on their trek of discovery across the northwest.

- Cale Case, is a native of Lander.

And from https://www.wyohistory.org/encyclopedia/lander-trail-national-road-building-comes-wyoming:

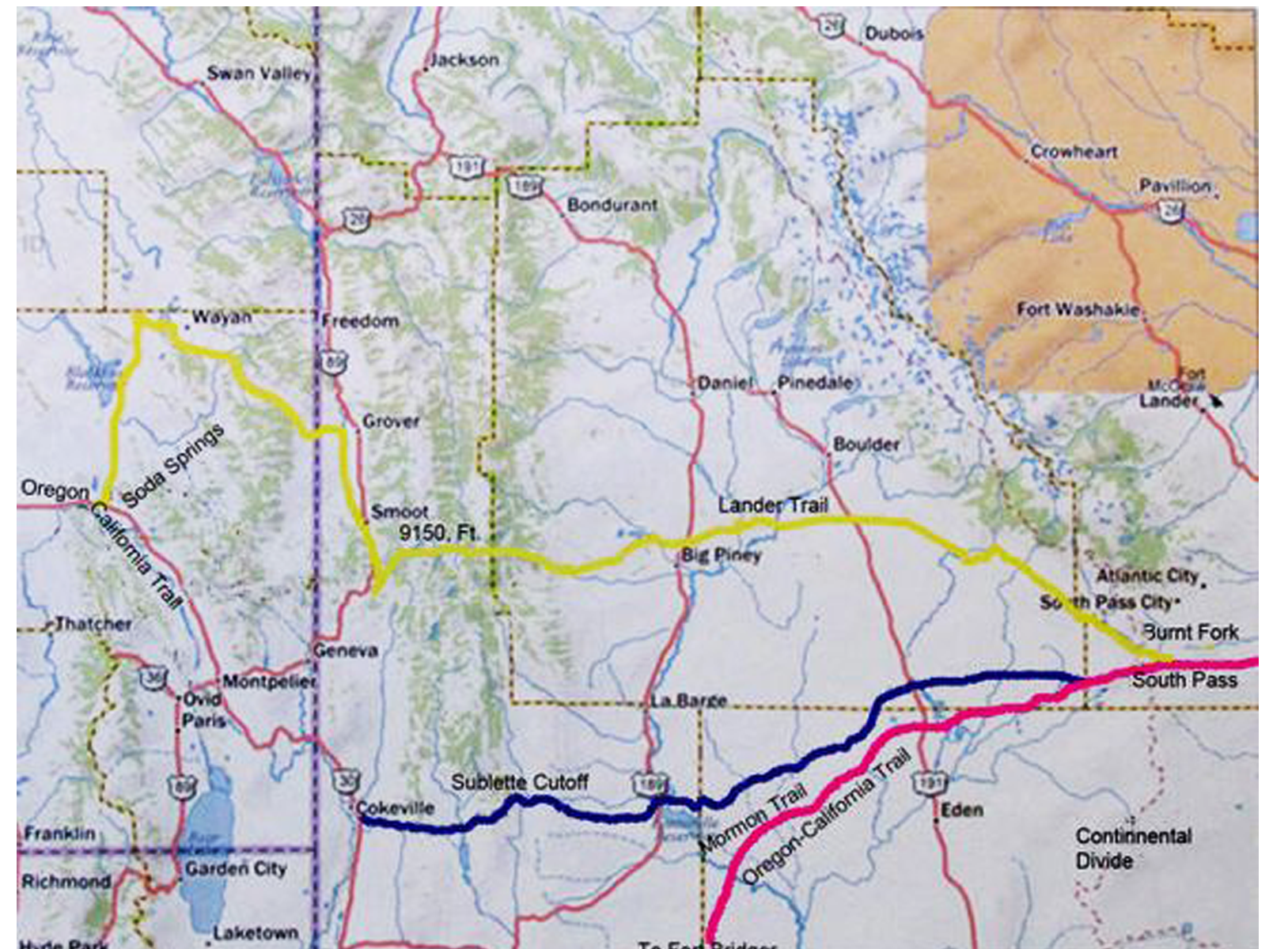

In 1857, with passage of the Pacific Wagon Road Act, Congress appropriated funds to survey and construct wagon roads. A segment of the first such national wagon road to be built in the West, now known as the Lander Trail, the Lander Road or Lander Cutoff, was named after the man in charge of its construction.

By the mid-nineteenth century, the U.S. government had a long history of helping create transportation infrastructure for the fledgling nation. However, the thousands of miles of emigrant trails that opened the vast expanses of the West had developed organically. The resulting spiderweb of cutoffs and supposed shortcuts created difficulties in the smooth flow of westward migration.

In 1846-1847, the ill-prepared Donner Party, for example, took bad advice from a commercially motivated, inaccurate guidebook and west of Fort Bridger in what’s now southwest Wyoming followed the Hastings Cutoff, named for the guidebook’s author. The result was starvation, death and cannibalism—an extreme example of the negative side of a transportation system based more on political and entrepreneurial whims than on sound engineering.

The military struggled to guard a road system that sprouted new routes as the author of the latest trail guide or some entrepreneur touted an easier, safer and shorter trip to given destinations. At the same time, each new route seemed likely to open new wounds with the original inhabitants of the plains, mountains and deserts, creating new difficulties for the government to manage. Something had to be done.

By 1857, Frederick William Lander was an accomplished railroad engineer and explorer. In those capacities, he had explored the foothills and passes of the Rocky Mountains, trailed the Souris River into Canada, trekked along the Columbia and Cowlitz rivers and mastered the passes of the Cascade Mountains. He was an able frontiersman and was reportedly rough on horses, with a hot temper and a reputation as a duelist.

Lander started as chief engineer on the proposed national wagon road, spending long days on horseback surveying potential routes. A few years earlier, he had scouted the South Pass of the Rockies in what’s now Wyoming as a potential railroad route. This experience made him an obvious choice to oversee construction of the new national road, with its planned route west of South Pass to City-of-Rocks in what’s now southeast Idaho.

He was not the first man to be selected as superintendent, however. That honor had gone to William Miller Finney Magraw. But in 1857, Magraw unexpectedly joined Albert Sidney Johnston’s expedition to re-establish federal authority in Utah Territory and to install federally appointed territorial officers. The move became known as the Utah War, and followed years of tension between the Mormons and the federal government over questions of sovereignty, polygamy, land rights, water rights and the authority of courts.

Lander was appointed in Magraw’s place in 1858. This replacement assured the national road was completed, because management of the project was transferred from a struggling drunkard to a highly competent and motivated captain. (Bad feeling continued between them, however. When the two superintendents met in Washington, D.C. in 1860, Magraw assaulted Lander with a blackjack, splitting open Lander’s head. Although severely injured, Lander beat Magraw nearly to death before being pulled away by several waiters.)

The national road, originally designated the Fort Kearney [sic], South Pass and Honey Lake Wagon Road, was designed to improve the extant California Trail system. Minor changes were made to the traditional California route on its eastern and western ends.

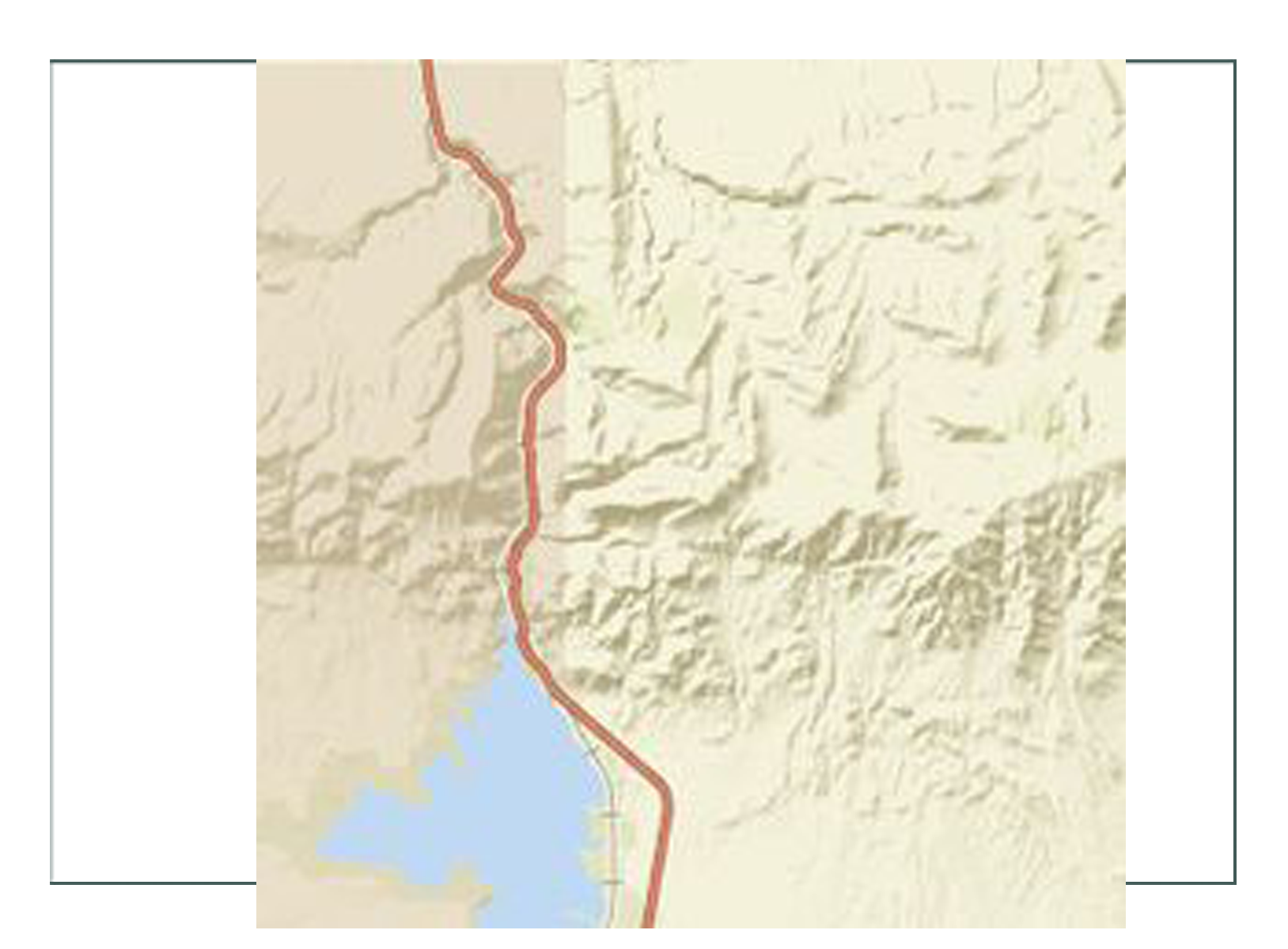

Significant modifications to the California Trail corridor were made starting in the South Pass area and going west to Fort Hall. The route between the trail’s final crossing of the Sweetwater River near South Pass and Fort Hall on the Snake River in what’s now southeastern Idaho, roughly 229 miles in length, is what came to be known as the Lander Trail. It was but a segment of a much longer road that stretched between Missouri and California.

Many believed that construction of the Lander Cutoff was intended to provide a route that avoided the Mormon settlements in Utah Territory. Following the ill-fated events at Mountain Meadows in September 1857, wherein California-bound emigrants of an Arkansas wagon train were murdered by Mormon militia, many travelers may have welcomed an alternate route.

However, many of the laborers Lander hired to build the new road were themselves Mormons from the Salt Lake Valley, making it seem unlikely the Army had any motives other than building a road that was safer because it was shorter.

Lander hired workers and laid out a route that made excellent use of terrain, available fodder, wood and water. His plan shortened the more traditional route from South Pass by way of Fort Bridger to Fort Hall by as much as 60 miles.

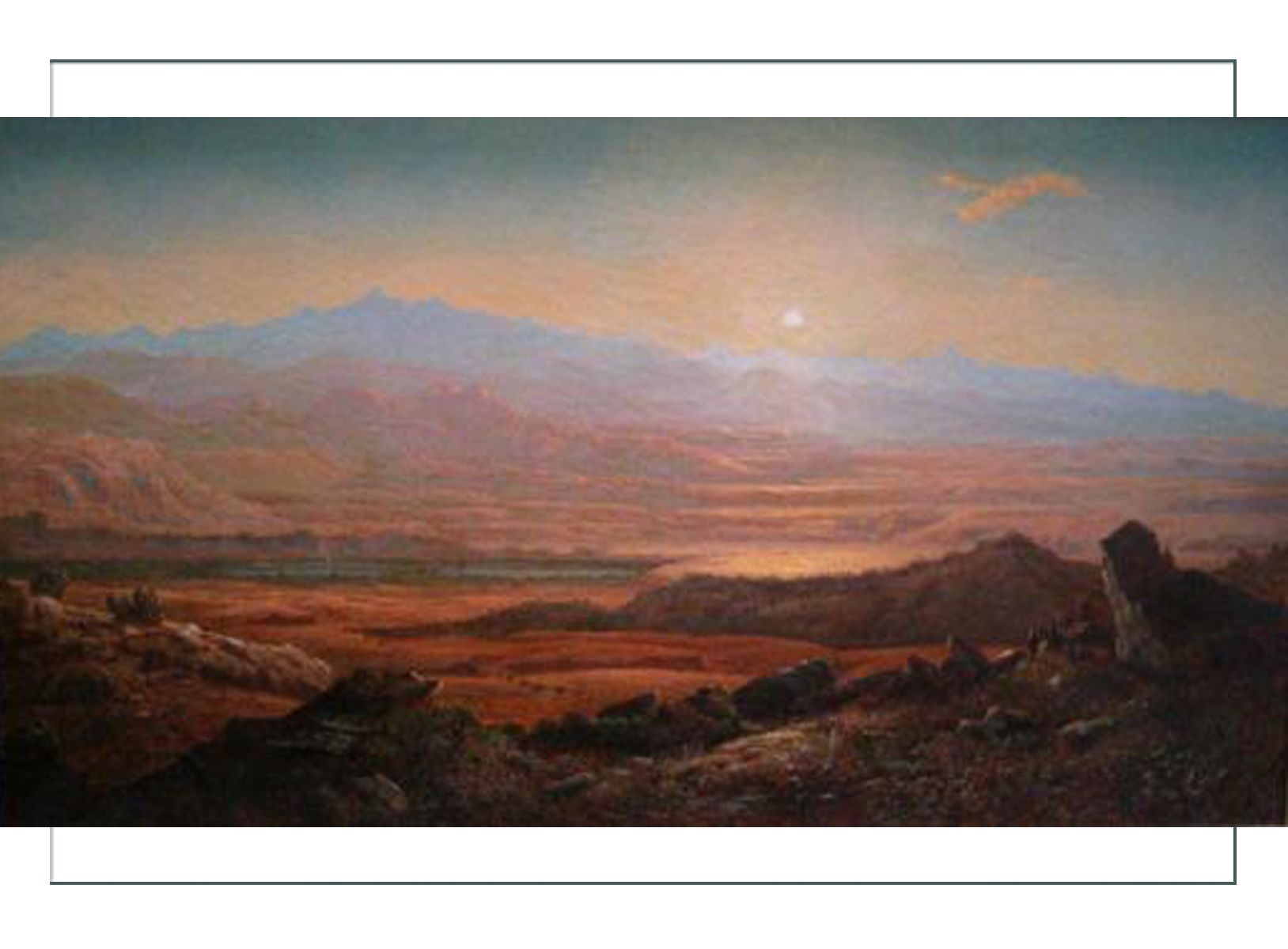

Lander’s road traversed some spectacular landscapes, with the snowcapped Wind River Mountains just to the north providing a stunning backdrop on the road’s eastern stretches. Despite Lander’s care in choosing the route, however, some emigrants noted difficult river crossings, such as the Buckskin Crossing of the Big Sandy. Lander’s route also ran through higher elevations for more of its length, thus making it more likely that travelers would encounter snow on the trail.

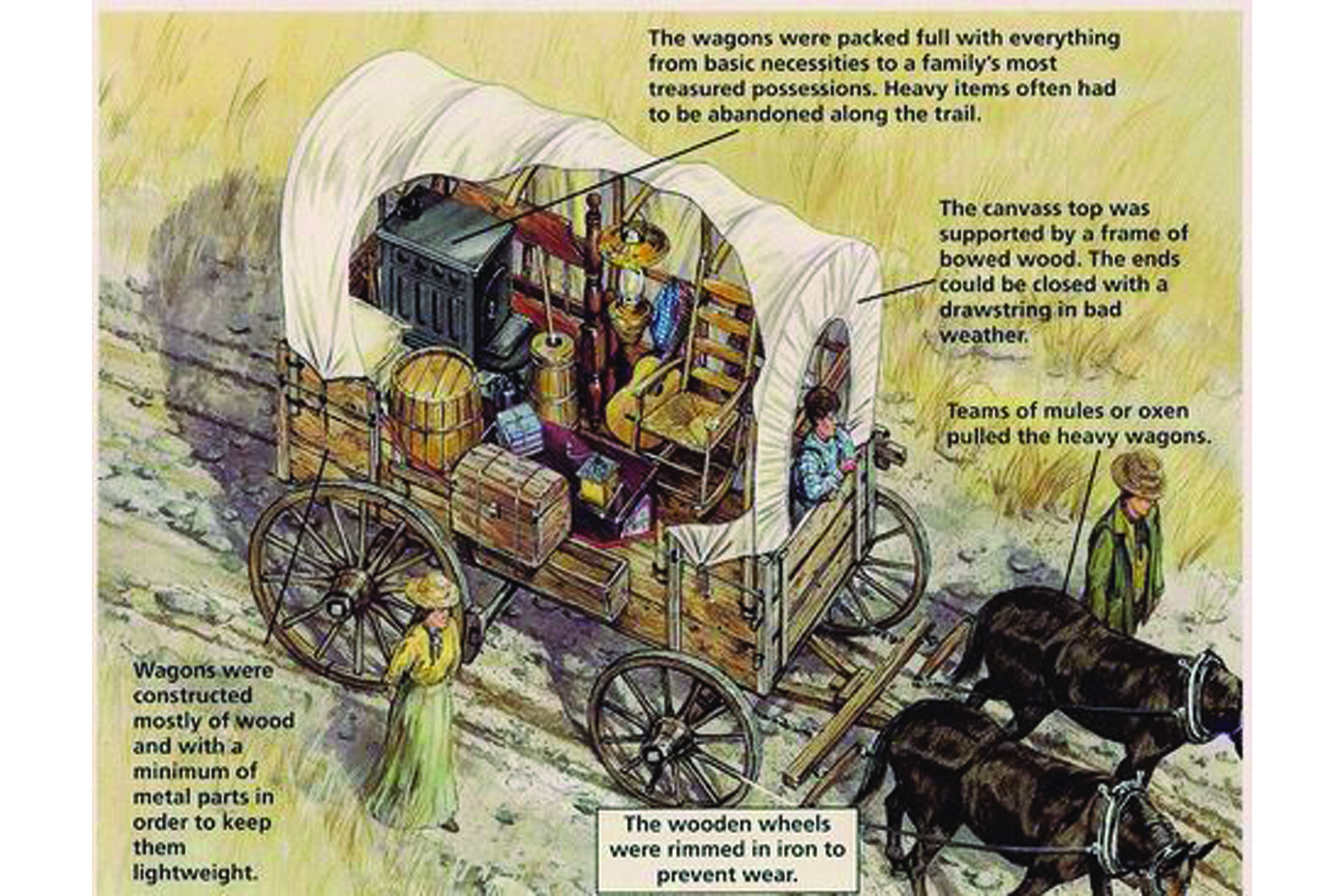

Most western wagon roads of the period were simply tracks worn into the ground by the passage of wagons and livestock. In contrast, much of the Lander Road was constructed. Lander’s workers moved roughly 62,000 cubic yards of earth and hewed trail through 11 miles of willow forests and 23 miles of pine forests. They built seven bridges, two corrals and, for safety, two blockhouses. Remarkably, the road was completed ahead of schedule and at a lower cost than expected. Lander also published, with government funds, an estimated 1,000 copies of a new trail guide advertising his route.

Before leaving his duties to return east, Lander assigned Charles Miller to supervise the new road from Gilbert’s Station at South Pass, but then withdrew the remainder of his men from the mountains. Miller did not survive the winter. He was murdered during an argument at the South Pass mail station.

Lander appointed Maj. Edmond Yates as Miller’s replacement. Yates persuaded large parties of emigrants to take the new road. Estimates of trail traffic are difficult to confirm, but the standard wisdom is that more than 100,000 people traveled on the Lander Trail. During peak years, such as 1859, the road may have been used by as many as 13,000 people, and during the Civil War, it became a favored option.

Overall, Lander’s placement of the road was well chosen. Always the perfectionist, Lander made slight modifications to avoid difficult segments of the trail, but found ways that allowed travelers to return to the planned route quickly. As with other wagon roads, Lander’s trail was altered by its users. They abandoned stretches that became unusable and created new variants.

An unexpected benefit of the construction of the Lander Trail was Lander’s inclusion of artists Albert Bierstadt, Francis Seth Frost and Henry Hitchens on his team. These men produced works showing a romantic West that encouraged many to journey to the land where the sun sets.

Lander eventually became a national hero, seen by the public as an adventurer in the mold of John C. Fremont. When the Civil War broke out, he joined the Union Army. His artillery unit fired the first shots in the first land battle of the war, at Philippi in what’s now West Virginia.

In May 1861, the month after the war began, he reached the rank of brigadier general in the Army of the Potomac. The following October he was wounded in the leg, yet soon was given command of a full division on the upper Potomac. In February 1862, however, he succumbed to “congestive chills”—probably pneumonia—and, after two weeks during which his requests for relief went unheeded, died on March 2, 1862.

At the time of his death he was mourned by the nation; 40,000 people including President Abraham Lincoln, his cabinet, military brass, senators, congressmen, and the Supreme Court attended his funeral in Washington, D.C.

The Lander Trail is one of the few monuments to this remarkable man that survives today. Yet, perhaps his greatest contribution—the central route for the transcontinental railroad, which Lander had spent years scouting and championing and which became the route of the Union Pacific—does not bear his name.

Surviving portions of the Lander Trail are now designated by the National Park Service as part of the California National Historic Trail. Much of the trail and its variants are located on public land and are open to visitation. Markers have been placed to allow visitors to follow the trail route, although some segments are difficult to track. Where the original road passes through private and state lands, permission of the landowner or lessee is required before visitors can be allowed access.

from https://travelwyoming.com/things-to-do/historic-sites

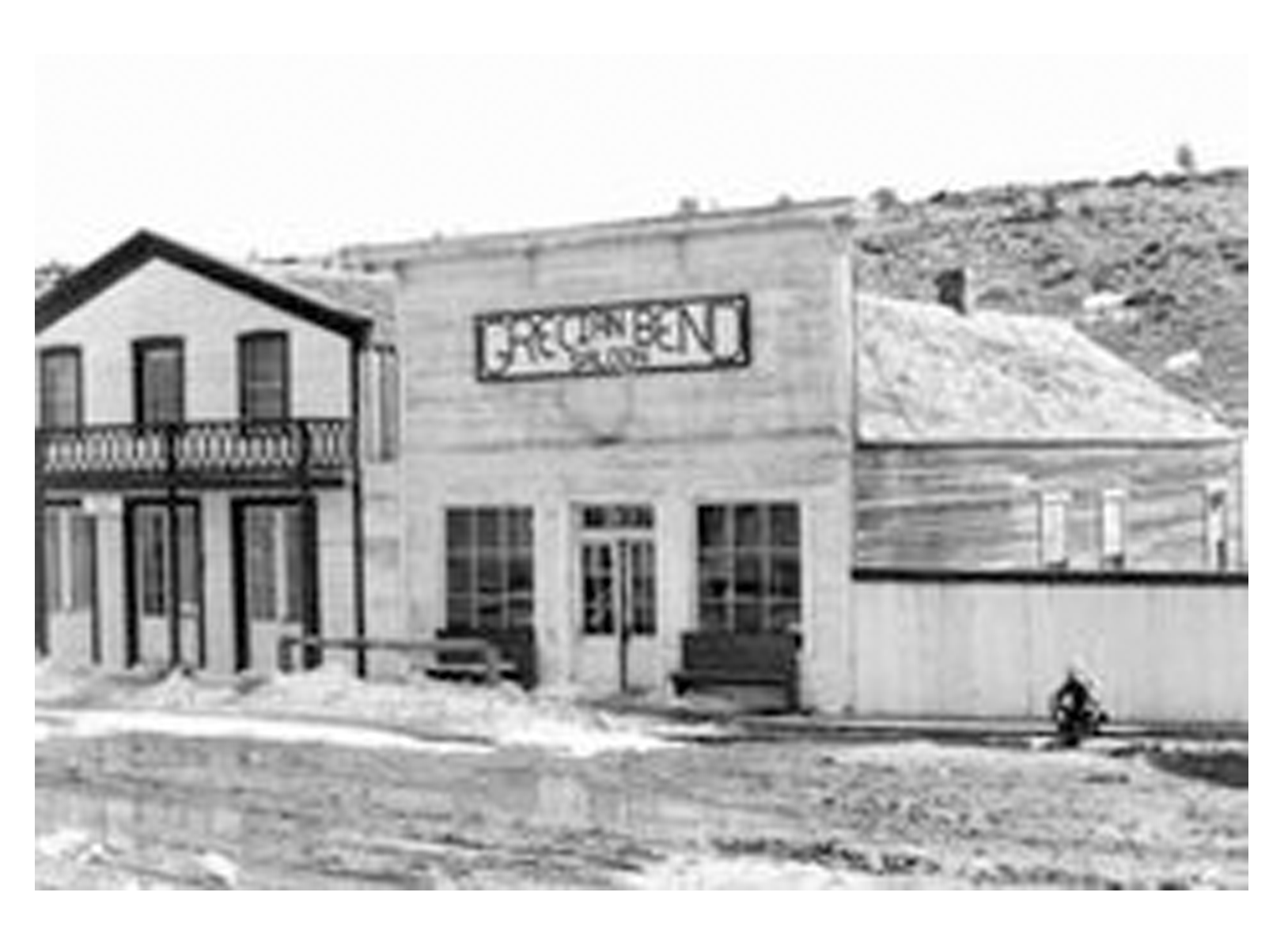

South Pass City, located 5 miles southwest of Lander, Wyoming, is a historic gold mining town and is one of Wyoming’s largest historic sites, with 24 historic structures, more than 30 period room exhibits, a visitors’ center, picnic areas and nature trails. Living history demonstrations, lectures and movies are presented on weekends throughout the summer, and the July 4th celebration is one of the oldest and biggest in the state. The historic site is open daily, from May 15 to Oct. 15.

Located north of the historic Oregon Trail, South Pass City was built in 1867 as a result of a gold mining boom in the Sweetwater Mining District. When the Carissa Mine struck a rich vein, hundreds of western prospectors rushed to the area hoping to finally find the mother lode. Within one year, the town’s population soared to 2,000 people and South Pass Avenue grew to a half mile in length as saloon owners, freighters, bankers, blacksmiths and other merchants followed the miners to South Pass.

More than 30 gold mines were open and dozens of sluicing operations dotted the scenic hillsides. South Pass City also played a key role in the women’s suffrage movement. William Bright, one of the town’s representatives in the Territorial Legislature in 1869, introduced a women’s suffrage bill. It passed and was signed by the governor, making Wyoming the first territory or state in the country where women could vote and hold political office. Just two months later, Esther Hobart Morris was appointed the town’s justice of the peace, becoming the nation’s first female judge. But, all booms must end. A bust hit the South Pass country in 1872, and most of the people moved away however, two more booms – ranching and lately tourism have kept South Pass City alive.

from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oregon_Trail

The Oregon Trail was a 2,170-mile (3,490 km)[1] east-west, large-wheeled wagon route and emigrant trail in the United States that connected the Missouri River to valleys in Oregon. The eastern part of the Oregon Trail spanned part of what is now the state of Kansas and nearly all of what are now the states of Nebraska and Wyoming. The western half of the trail spanned most of the current states of Idaho and Oregon.

The Oregon Trail was laid by fur traders and trappers from about 1811 to 1840, and was only passable on foot or by horseback. By 1836, when the first migrant wagon train was organized in Independence, Missouri, a wagon trail had been cleared to Fort Hall, Idaho. Wagon trails were cleared increasingly farther west, and eventually reached all the way to the Willamette Valley in Oregon, at which point what came to be called the Oregon Trail was complete, even as almost annual improvements were made in the form of bridges, cutoffs, ferries, and roads, which made the trip faster and safer. From various starting points in Iowa, Missouri, or Nebraska Territory, the routes converged along the lower Platte River Valley near Fort Kearny, Nebraska Territory, and led to rich farmlands west of the Rocky Mountains.

From the early to mid-1830s (and particularly through the years 1846–1869) the Oregon Trail and its many offshoots were used by about 400,000 settlers, farmers, miners, ranchers, and business owners and their families. The eastern half of the trail was also used by travelers on the California Trail (from 1843), Mormon Trail (from 1847), and Bozeman Trail (from 1863), before turning off to their separate destinations. Use of the trail declined as the First Transcontinental Railroad was completed in 1869, making the trip west substantially faster, cheaper, and safer. Today, modern highways, such as Interstate 80 and Interstate 84, follow parts of the same course westward and pass through towns originally established to serve those using the Oregon Trail.

When American emigration over the Oregon Trail began in earnest in the early 1840s, for many settlers the fort became the last stop on the Oregon Trail where they could get supplies, aid and help before starting their homesteads.[8] Fort Vancouver was the main re-supply point for nearly all Oregon trail travelers until U.S. towns could be established. The HBC established Fort Colvile in 1825 on the Columbia River near Kettle Falls as a good site to collect furs and control the upper Columbia River fur trade.[9] Fort Nisqually was built near the present town of DuPont, Washington and was the first HBC fort on Puget Sound. Fort Victoria was erected in 1843 and became the headquarters of operations in British Columbia, eventually growing into modern-day Victoria, the capital city of British Columbia.

The Oregon Country/Columbia District stretched from 42’N to 54 40’N. The most heavily disputed portion is highlighted.

By 1840 the HBC had three forts: Fort Hall (purchased from Nathaniel Jarvis Wyeth in 1837), Fort Boise and Fort Nez Perce on the western end of the Oregon Trail route as well as Fort Vancouver near its terminus in the Willamette Valley. With minor exceptions they all gave substantial and often desperately needed aid to the early Oregon Trail pioneers.

When the fur trade slowed in 1840 because of fashion changes in men’s hats, the value of the Pacific Northwest to the British was seriously diminished. Canada had few potential settlers who were willing to move more than 2,500 miles (4,000 km) to the Pacific Northwest, although several hundred ex-trappers, British and American, and their families did start settling in Oregon, Washington and California. They used most of the York Express route through northern Canada. In 1841, James Sinclair, on orders from Sir George Simpson, guided nearly 200 settlers from the Red River Colony (located at the junction of the Assiniboine River and Red River near present Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada) into the Oregon territory.[10][11] This attempt at settlement failed when most of the families joined the settlers in the Willamette Valley, with their promise of free land and HBC-free government.

In 1846, the Oregon Treaty ending the Oregon boundary dispute was signed with Britain. The British lost the land north of the Columbia River they had so long controlled. The new Canada–United States border was established much further north at the 49th parallel. The treaty granted the HBC navigation rights on the Columbia River for supplying their fur posts, clear titles to their trading post properties allowing them to be sold later if they wanted, and left the British with good anchorages at Vancouver and Victoria. It gave the United States what it mostly wanted, a “reasonable” boundary and a good anchorage on the West Coast in Puget Sound. While there were almost no United States settlers in the future state of Washington in 1846, the United States had already demonstrated it could induce thousands of settlers to go to the Oregon Territory, and it would be only a short time before they would vastly outnumber the few hundred HBC employees and retirees living in Washington

Up to 3,000 mountain men were trappers and explorers, employed by various British and United States fur companies or working as free trappers, who roamed the North American Rocky Mountains from about 1810 to the early 1840s. They usually traveled in small groups for mutual support and protection.

Trapping took place in the fall when the fur became prime. Mountain men primarily trapped beaver and sold the skins. A good beaver skin could bring up to $4 at a time when a man’s wage was often $1 per day. Some were more interested in exploring the West. In 1825, the first significant American Rendezvous occurred on the Henry’s Fork of the Green River. The trading supplies were brought in by a large party using pack trains originating on the Missouri River. These pack trains were then used to haul out the fur bales. They normally used the north side of the Platte River—the same route used 20 years later by the Mormon Trail.

For the next 15 years the American rendezvous was an annual event moving to different locations, usually somewhere on the Green River in the future state of Wyoming. Each rendezvous, occurring during the slack summer period, allowed the fur traders to trade for and collect the furs from the trappers and their Native American allies without having the expense of building or maintaining a fort or wintering over in the cold Rockies. In only a few weeks at a rendezvous a year’s worth of trading and celebrating would take place as the traders took their furs and remaining supplies back east for the winter and the trappers faced another fall and winter with new supplies.

Trapper Jim Beckwourth described the scene as one of “Mirth, songs, dancing, shouting, trading, running, jumping, singing, racing, target-shooting, yarns, frolic, with all sorts of extravagances that white men or Indians could invent.”[14] In 1830, William Sublette brought the first wagons carrying his trading goods up the Platte, North Platte, and Sweetwater rivers before crossing over South Pass to a fur trade rendezvous on the Green River near the future town of Big Piney, Wyoming. He had a crew that dug out the gullies and river crossings and cleared the brush where needed. This established that the eastern part of most of the Oregon Trail was passable by wagons.

In the late 1830s the HBC instituted a policy intended to destroy or weaken the American fur trade companies. The HBC’s annual collection and re-supply Snake River Expedition was transformed to a trading enterprise. Beginning in 1834, it visited the American Rendezvous to undersell the American traders—losing money but undercutting the American fur traders. By 1840 the fashion in Europe and Britain shifted away from the formerly very popular beaver felt hats and prices for furs rapidly declined and the trapping almost ceased.

Fur traders tried to use the Platte River, the main route of the eastern Oregon Trail, for transport but soon gave up in frustration as its many channels and islands combined with its muddy waters were too shallow, crooked and unpredictable to use for water transport. The Platte proved to be unnavigable. The Platte River and North Platte River Valley, however, became an easy roadway for wagons, with its nearly flat plain sloping easily up and heading almost due west.

John C. Frémont of the U.S. Army’s Corps of Topographical Engineers and his guide Kit Carson led three expeditions from 1842 to 1846 over parts of California and Oregon. His explorations were written up by him and his wife Jessie Benton Frémont and were widely published. The first detailed map of California and Oregon were drawn by Frémont and his topographers and cartographers in about 1848.[16]

More on the Lander Trail & Oregon Trail Offshoots

The Oregon trail was still in use during the Civil War, but traffic declined after 1855 when the Panama Railroad across the Isthmus of Panama was completed. Paddle wheel steamships and sailing ships, often heavily subsidized to carry the mail, provided rapid transport to and from the east coast and New Orleans, Louisiana, to and from Panama to ports in California and Oregon.

Over the years many ferries were established to help get across the many rivers on the path of the Oregon Trail. Multiple ferries were established on the Missouri River, Kansas River, Little Blue River, Elkhorn River, Loup River, Platte River, South Platte River, North Platte River, Laramie River, Green River, Bear River, two crossings of the Snake River, John Day River, Deschutes River, Columbia River, as well as many other smaller streams. During peak immigration periods several ferries on any given river often competed for pioneer dollars. These ferries significantly increased speed and safety for Oregon Trail travelers. They increased the cost of traveling the trail by roughly $30 per wagon but increased the speed of the transit from about 160 to 170 days in 1843 to 120 to 140 days in 1860. Ferries also helped prevent death by drowning at river crossings.[38]

In April 1859, an expedition of U.S. Corps of Topographical Engineers led by Captain James H. Simpson left Camp Floyd, Utah, to establish an army supply route across the Great Basin to the eastern slope of the Sierras. Upon return in early August, Simpson reported that he had surveyed the Central Overland Route from Camp Floyd to Genoa, Nevada. This route went through central Nevada (roughly where U.S. Route 50 goes today) and was about 280 miles (450 km) shorter than the “standard” Humboldt River California trail route.[39]

The Army improved the trail for use by wagons and stagecoaches in 1859 and 1860. Starting in 1860, the American Civil War closed the heavily subsidized Butterfield Overland Mail stage Southern Route through the deserts of the American Southwest.

In 1860–61 the Pony Express, employing riders traveling on horseback day and night with relay stations about every 10 miles (16 km) to supply fresh horses, was established from St. Joseph, Missouri, to Sacramento, California. The Pony Express built many of their eastern stations along the Oregon/California/Mormon/Bozeman trails and many of their western stations along the very sparsely settled Central Route across Utah and Nevada.[40] The Pony Express delivered mail summer and winter in roughly 10 days from the midwest to California.

In 1861, John Butterfield, who since 1858 had been using the Butterfield Overland Mail, also switched to the Central Route to avoid traveling through hostile territories during the American Civil War. George Chorpenning immediately realized the value of this more direct route, and shifted his existing mail and passenger line along with their stations from the “Northern Route” (California Trail) along the Humboldt River. In 1861, the First Transcontinental Telegraph also laid its lines alongside the Central Overland Route. Several stage lines were set up carrying mail and passengers that traversed much of the route of the original Oregon Trail to Fort Bridger and from there over the Central Overland Route to California.

By traveling day and night with many stations and changes of teams (and extensive mail subsidies), these stages could get passengers and mail from the midwest to California in about 25 to 28 days. These combined stage and Pony Express stations along the Oregon Trail and Central Route across Utah and Nevada were joined by the First Transcontinental Telegraph stations and telegraph line, which followed much the same route in 1861 from Carson City, Nevada to Salt Lake City. The Pony Express folded in 1861 as they failed to receive an expected mail contract from the U.S. government and the telegraph filled the need for rapid east–west communication. This combination wagon/stagecoach/pony express/telegraph line route is labeled the Pony Express National Historic Trail on the National Trail Map.[40] From Salt Lake City the telegraph line followed much of the Mormon/California/Oregon trails to Omaha, Nebraska.

After crossing the South Platte the trail continues up the North Platte River, crossing many small swift-flowing creeks. Fort Laramie, at the confluence of the Laramie and North Platte rivers, was a major stopping point. Fort Laramie was a former fur trading outpost originally named Fort John that was purchased in 1848 by the U.S. Army to protect travelers on the trails.[52] It was the last army outpost till travelers reached the coast. As the North Platte veers to the south, the trail crosses the North Platte to the Sweetwater River Valley, which heads almost due west. Independence Rock is on the Sweetwater River. The Sweetwater would have to be crossed up to nine times before the trail crosses over the Continental Divide at South Pass, Wyoming.

Fort Laramie was the end of most cholera outbreaks which killed thousands along the lower Platte and North Platte from 1849 to 1855. Spread by cholera bacteria in fecal contaminated water, cholera caused massive diarrhea, leading to dehydration and death. In those days its cause and treatment were unknown, and it was often fatal—up to 30 percent of infected people died. It is believed that the swifter flowing rivers in Wyoming helped prevent the germs from spreading.[53]

From South Pass the trail continues southwest crossing Big Sandy Creek—about 10 feet (3.0 m) wide and 1 foot (0.30 m) deep—before hitting the Green River. Three to five ferries were in use on the Green during peak travel periods. The deep, wide, swift, and treacherous Green River which eventually empties into the Colorado River, was usually at high water in July and August, and it was a dangerous crossing. After crossing the Green, the main trail continued approximately southwest until the Blacks Fork of the Green River and Fort Bridger. From Fort Bridger the Mormon Trail continued southwest following the upgraded Hastings Cutoff through the Wasatch Mountains.[54] From Fort Bridger, the main trail, comprising several variants, veered northwest over the Bear River Divide and descended to the Bear River Valley. The trail turned north following the Bear River past the terminus of the Sublette-Greenwood Cutoff at Smiths Fork and on to the Thomas Fork Valley at the present Wyoming–Idaho border.[55]

Over time, two major heavily used cutoffs were established in Wyoming. The Sublette-Greenwood Cutoff was established in 1844 and cut about 70 miles (110 km) off the main route. It leaves the main trail about 10 miles (16 km) west of South Pass and heads almost due west crossing Big Sandy Creek and then about 45 miles (72 km) of waterless, very dusty desert before reaching the Green River near the present town of La Barge. Ferries here transferred them across the Green River. From there the Sublette-Greenwood Cutoff trail had to cross a mountain range to connect with the main trail near Cokeville in the Bear River Valley.[56]

The Lander Road, formally the Fort Kearney, South Pass, and Honey Lake Wagon Road, was established and built by U.S. government contractors in 1858–59.[57] It was about 80 miles (130 km) shorter than the main trail through Fort Bridger with good grass, water, firewood and fishing but it was a much steeper and rougher route, crossing three mountain ranges. In 1859, 13,000[58] of the 19,000[59] emigrants traveling to California and Oregon used the Lander Road. The traffic in later years is undocumented.

The Lander Road departs the main trail at Burnt Ranch near South Pass, crosses the Continental Divide north of South Pass and reaches the Green River near the present town of Big Piney, Wyoming. From there the trail followed Big Piney Creek west before passing over the 8,800 feet (2,700 m) Thompson Pass in the Wyoming Range. It then crosses over the Smith Fork of the Bear River before ascending and crossing another 8,200-foot (2,500 m) pass on the Salt River Range of mountains and then descending into Star Valley.

It exited the mountains near the present Smith Fork road about 6 miles (9.7 km) south of the town of Smoot. The road continued almost due north along the present day Wyoming–Idaho western border through Star Valley. To avoid crossing the Salt River (which drains into the Snake River) which runs down Star Valley the Lander Road crossed the river when it was small and stayed west of the Salt River. After traveling down the Salt River Valley (Star Valley) about 20 miles (32 km) north the road turned almost due west near the present town of Auburn, and entered into the present state of Idaho along Stump Creek. In Idaho, it followed the Stump Creek valley northwest until it crossed the Caribou Mountains and proceeded past the south end of Grays Lake. The trail then proceeded almost due west to meet the main trail at Fort Hall; alternatively, a branch trail headed almost due south to meet the main trail near the present town of Soda Springs.[60][61]

Numerous landmarks are located along the trail in Wyoming including Independence Rock, Ayres Natural Bridge and Register Cliff.

Emigration West

from https://www.familysearch.org/wiki/en/Wyoming_Emigration_and_Immigration

Until 1811, when fur traders first opened a trail through the area, Wyoming was the domain of the American Indians. Between 1825 and 1840, about 200 mountain men bartered with the Indians at rendezvous in the region.

In the 1840s and 1850s, many thousands of emigrants traveling the Oregon Trail to California, Utah, and other western states passed through the North Platte and Sweetwater valleys and South Pass in central Wyoming. In the 1860s, as Indian troubles increased in the north, many emigrants preferred the more southerly Overland Trail through Bridger Pass. Until the railroad came, very few emigrants stayed in Wyoming.

The discovery of gold in 1867 at South Pass brought many immigrants to western Wyoming. A greater stimulus to settlement was the building of the transcontinental railroad in the late 1860s. Many Irish and Mexican laborers and Civil War veterans helped build the railway. Settlers from the Midwest followed the railroad into Wyoming, and built Cheyenne, Laramie, and other towns along the route. In the 1870s and 1880s, cattlemen from Texas drove herds into northern Wyoming.

Many Idaho Latter-day Saints came into Star Valley in the 1870s and 1880s. There were Latter-day Saint colonists in the Big Horn Basin by 1895, but the main body of Latter-day Saint settlers came there as an organized group from Utah and Idaho in 1900. A helpful source of information on these settlers in the Big Horn Basin is outlined below as taken from extensive research published in a book.

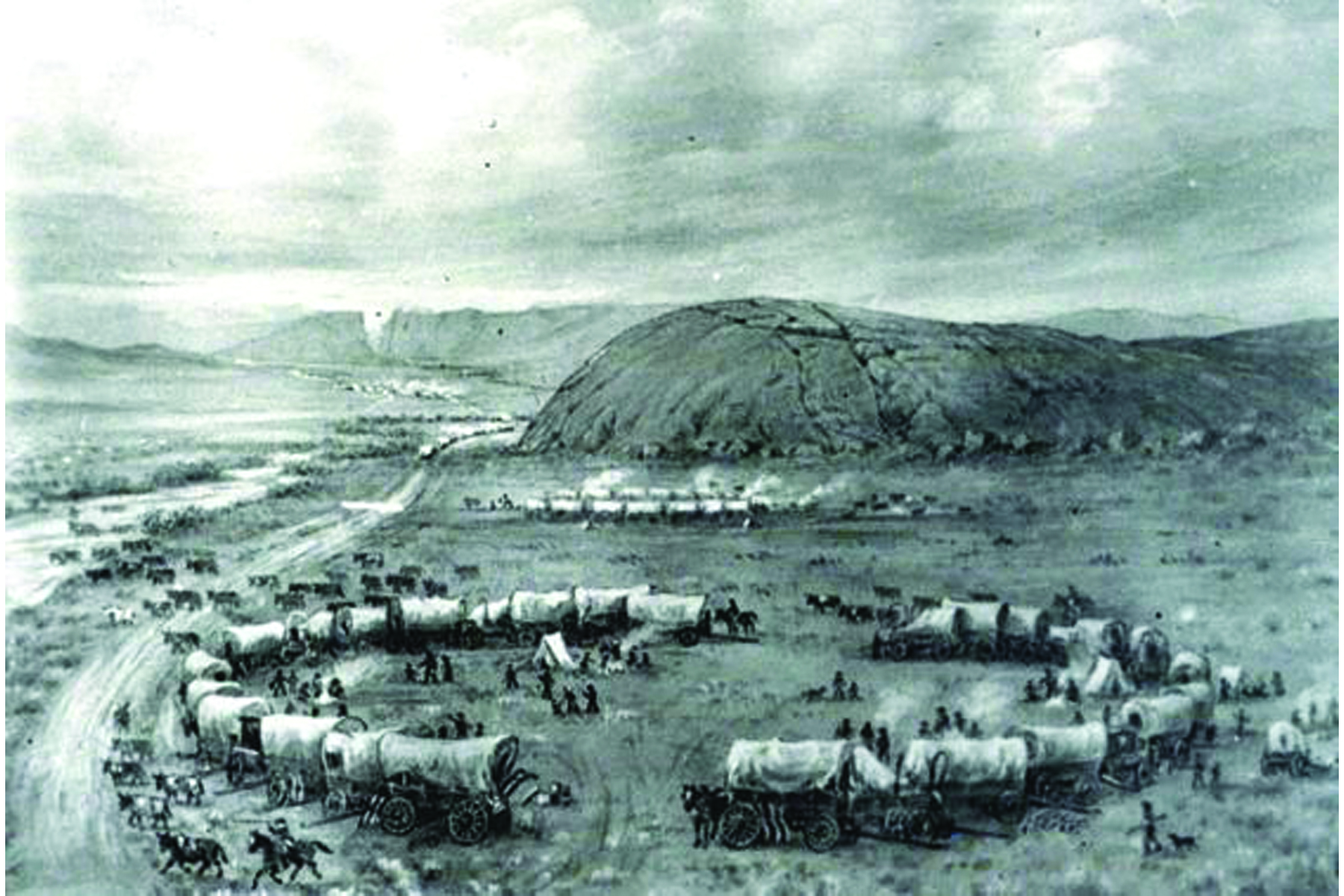

In what was dubbed “The Great Migration of 1843” or the “Wagon Train of 1843”, an estimated 700 to 1,000 emigrants left for Oregon.[21][22] They were led initially by John Gantt, a former U.S. Army Captain and fur trader who was contracted to guide the train to Fort Hall for $1 per person. The winter before, Marcus Whitman had made a brutal mid-winter trip from Oregon to St. Louis to appeal a decision by his mission backers to abandon several of the Oregon missions. He joined the wagon train at the Platte River for the return trip.

When the pioneers were told at Fort Hall by agents from the Hudson’s Bay Company that they should abandon their wagons there and use pack animals the rest of the way, Whitman disagreed and volunteered to lead the wagons to Oregon. He believed the wagon trains were large enough that they could build whatever road improvements they needed to make the trip with their wagons.

The biggest obstacle they faced was in the Blue Mountains of Oregon where they had to cut and clear a trail through heavy timber. The wagons were stopped at The Dalles, Oregon, by the lack of a road around Mount Hood. The wagons had to be disassembled and floated down the treacherous Columbia River and the animals herded over the rough Lolo trail to get by Mt. Hood. Nearly all of the settlers in the 1843 wagon trains arrived in the Willamette Valley by early October. A passable wagon trail now existed from the Missouri River to The Dalles. Jesse Applegate’s account of the emigration, “A Day with the Cow Column in 1843,” has been described as “the best bit of literature left to us by any participant in the [Oregon] pioneer movement…”[23] and has been republished several times from 1868 to 1990.[24]

In 1846, the Barlow Road was completed around Mount Hood, providing a rough but completely passable wagon trail from the Missouri River to the Willamette Valley: about 2,000 miles (3,200 km).

Consensus interpretations, as found in John Faragher’s book, Women and Men on the Overland Trail (1979), held that men and women’s power within marriage was uneven. This meant that women did not experience the trail as liberating, but instead only found harder work than they had handled back east.

Men and women’s power within marriage was uneven. This meant that women did not experience the trail as liberating, but instead only found harder work than they had handled back east. However, feminist scholarship, by historians such as Lillian Schlissel,[25] Sandra Myres,[26] and Glenda Riley,[27] suggests men and women did not view the West and western migration in the same way. Whereas men might deem the dangers of the trail acceptable if there was a strong economic reward at the end, women viewed those dangers as threatening to the stability and survival of the family.

Once they arrived at their new western home, women’s public role in building western communities and participating in the western economy gave them a greater authority than they had known back East. There was a “female frontier” that was distinct and different from that experienced by men.[28] (in other words, it was the women who “settled” meaning built schools, churches, organizations, and government, especially in Wyoming (see history of Cheyenne for records of such.

Women’s diaries kept during their travels or the letters they wrote home once they arrived at their destination supports these contentions. Women wrote with sadness and concern of the numerous deaths along the trail. Anna Maria King wrote to her family in 1845 about her trip to the Luckiamute Valley Oregon and of the multiple deaths experienced by her traveling group:

But listen to the deaths: Sally Chambers, John King and his wife, their little daughter Electa and their babe, a son 9 months old, and Dulancy C. Norton’s sister are gone. Mr. A. Fuller lost his wife and daughter Tabitha. Eight of our two families have gone to their long home.[29]

Similarly, emigrant Martha Gay Masterson, who traveled the trail with her family at the age of 13, mentioned the fascination she and other children felt for the graves and loose skulls they would find near their camps.[30]

Anna Maria King, like many other women, also advised family and friends back home of the realities of the trip and offered advice on how to prepare for the trip. Women also reacted and responded, often enthusiastically, to the landscape of the West. Betsey Bayley in a letter to her sister, Lucy P. Griffith described how travelers responded to the new environment they encountered:

“The mountains looked like volcanoes and the appearance that one day there had been an awful thundering of volcanoes and a burning world. The valleys were all covered with a white crust and looked like salaratus. Some of the company used it to raise their bread.[31]”

Summarization of the book “Pioneer Women” by Peavy & Smith:

Heading West – Many Times

Prior to 1840, documentation of settlement of regions west of the Mississippi River by Anglo-Americans could have been called “HIStory”. There were almost no women other than those indigenous who had been born to the Nations.

Land mapped by the Lewis and Clark Expedition of 1804, and subsequent acquistions by the United States government, however, opened up the northwest of what is the current US in what was known then as the Oregon Territory. At that time, that meant the entire Pacific coast to the Continental Divide which ran roughly along the western side of what would become the state of Wyoming.

News of missionary couples like Narcissa and Marcus Whitman successfully crossing the country to work throughout and establish missions all over the west, inspired others to come west. With the passage of the Preemption Act of 1842, the government gave any man over the age of 18 640 acres in the Territory, plus 160 more acres to his wife and each dependent child. This inspired not only westward emigration, but marriages and children.

Ownership of land at the time was the definition of success. To be able to live independently and to have your own home was enticing to many who were living in the burgeoning cities along the east coast. Some were first timers, but most had already moved before.

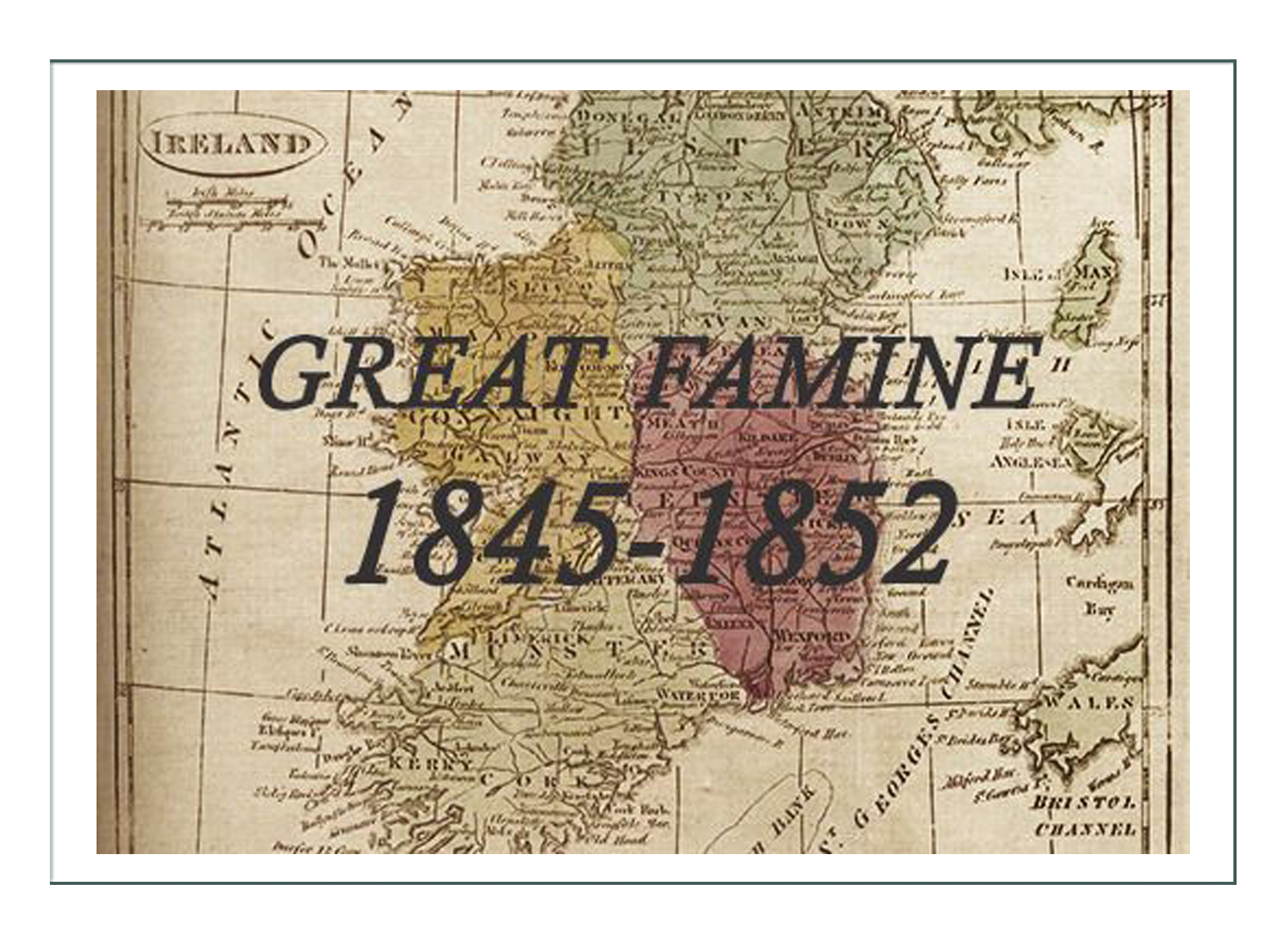

Many of these emigrants were not new to moving on. Most had already made a migratory move towards the west at least one time, and many 2 or 3 times. For some that first move was away from places like Ireland which was in the middle of a famine. Many came from the British Isles or other places in Northern Europe and went direction to the Oregon Territories.

For others born in the United States on the east coast it might have been to Kentucky, and then on to Missouri, or to Iowa and then Minnesota. Many went to the Dakotas, Nebraska, or areas south and west, like the Texas and Arizona Territories, although those were not quite being settled yet.

Those who settled first broke the trails for all who would follow, so it became easier and easier to make the move. As the years progressed, there were services provided to travelers such as mercantiles, hotels, ferries, and blacksmiths. Many of these would become permanent settlements where often, the pioneers would decide to stop and stay instead of continuing on. Sometimes it was because women had lost their husbands on the trip and couldn’t go on. Sometimes it was because of illness or because they felt they could contribute.

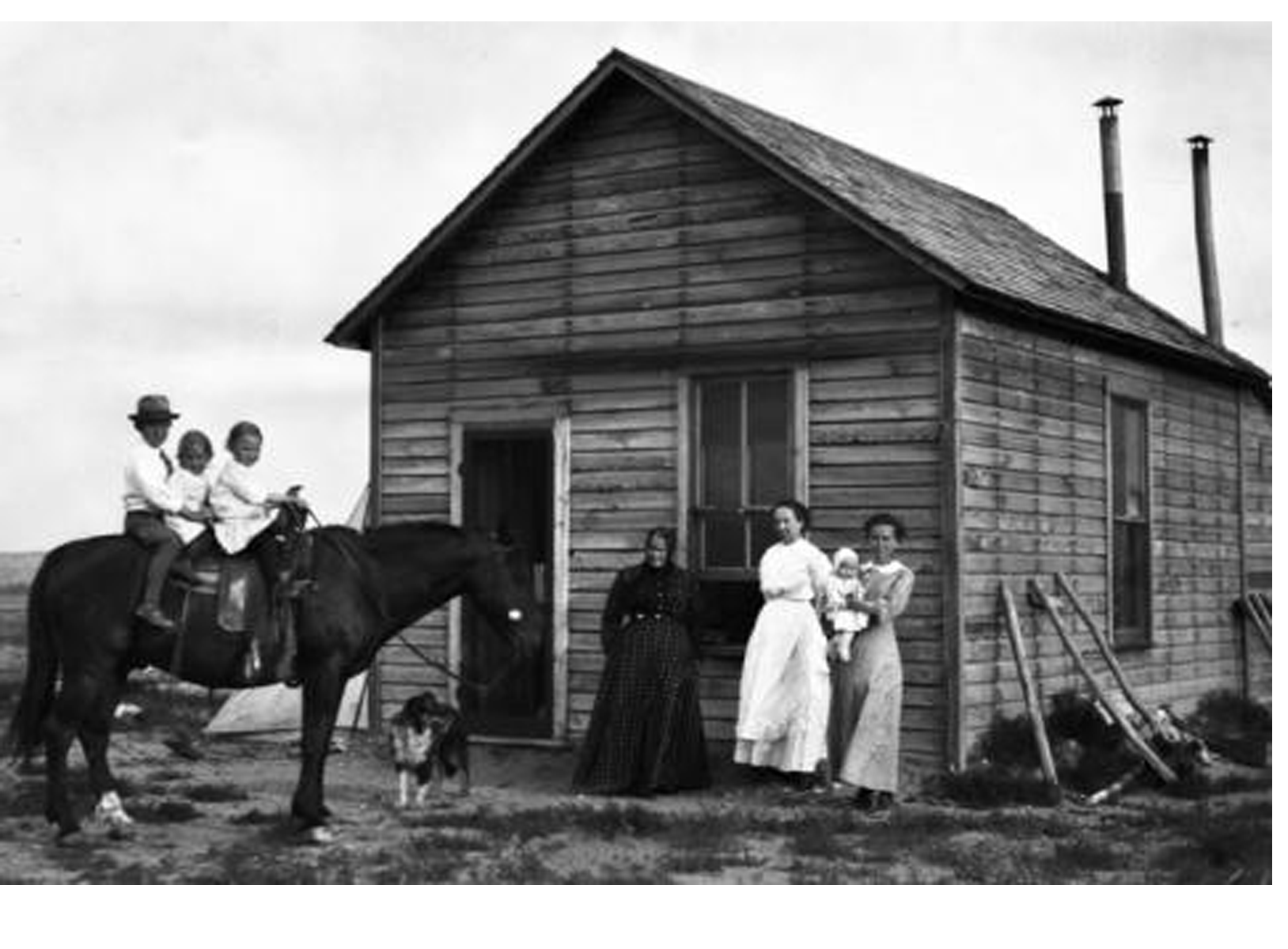

The emigrants, now pioneers as they “broke” the lands west, usually left established homes to go to an unsettled region. When they got to their new places, they worked to re create what they had left behind: churches, organizations, hospitals, schools, theaters, and such. Before that could happen, there was struggle, hard work, and deprivation of all sorts.

Life as a Pioneer – The Early Days of Settlement

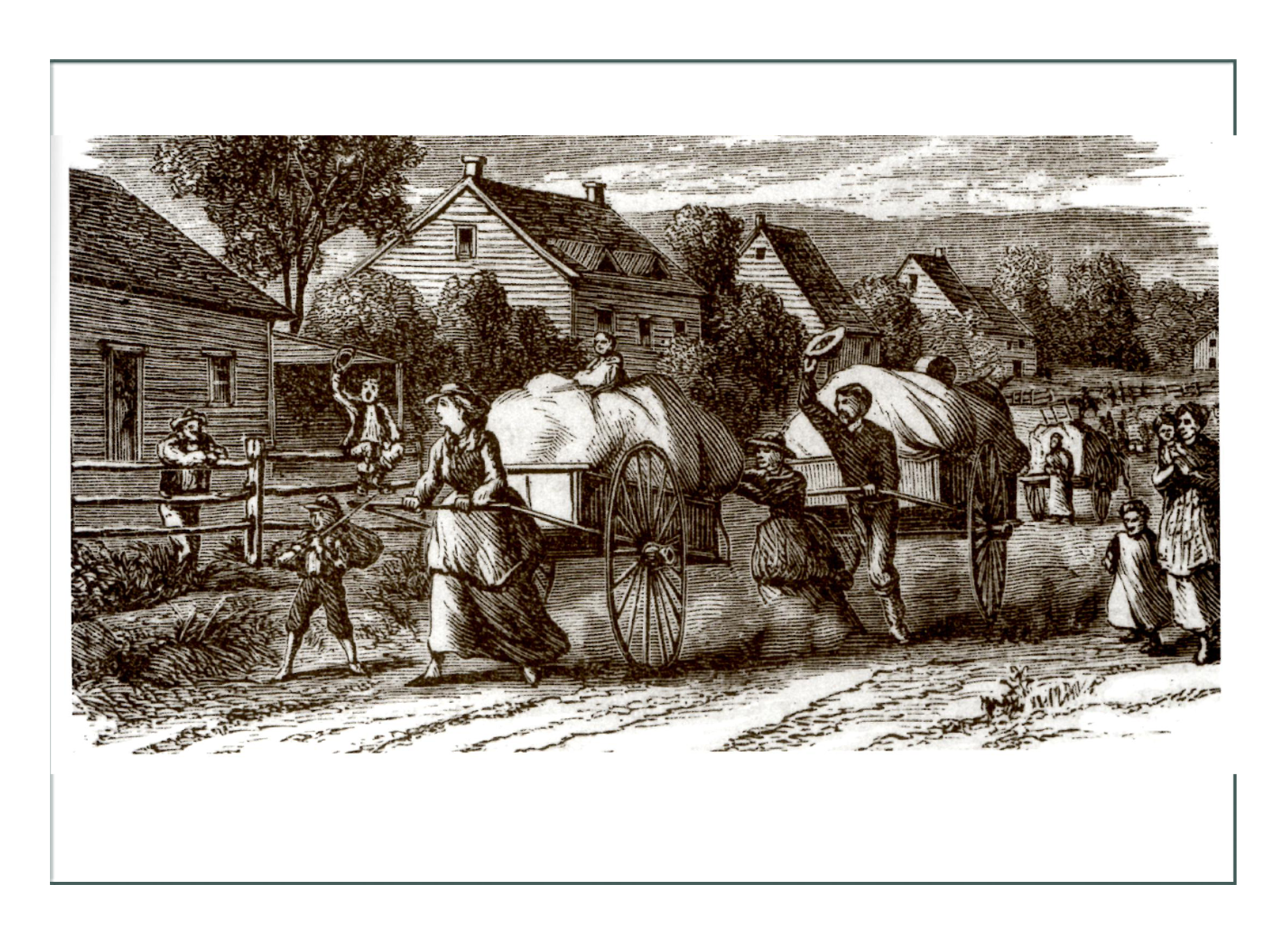

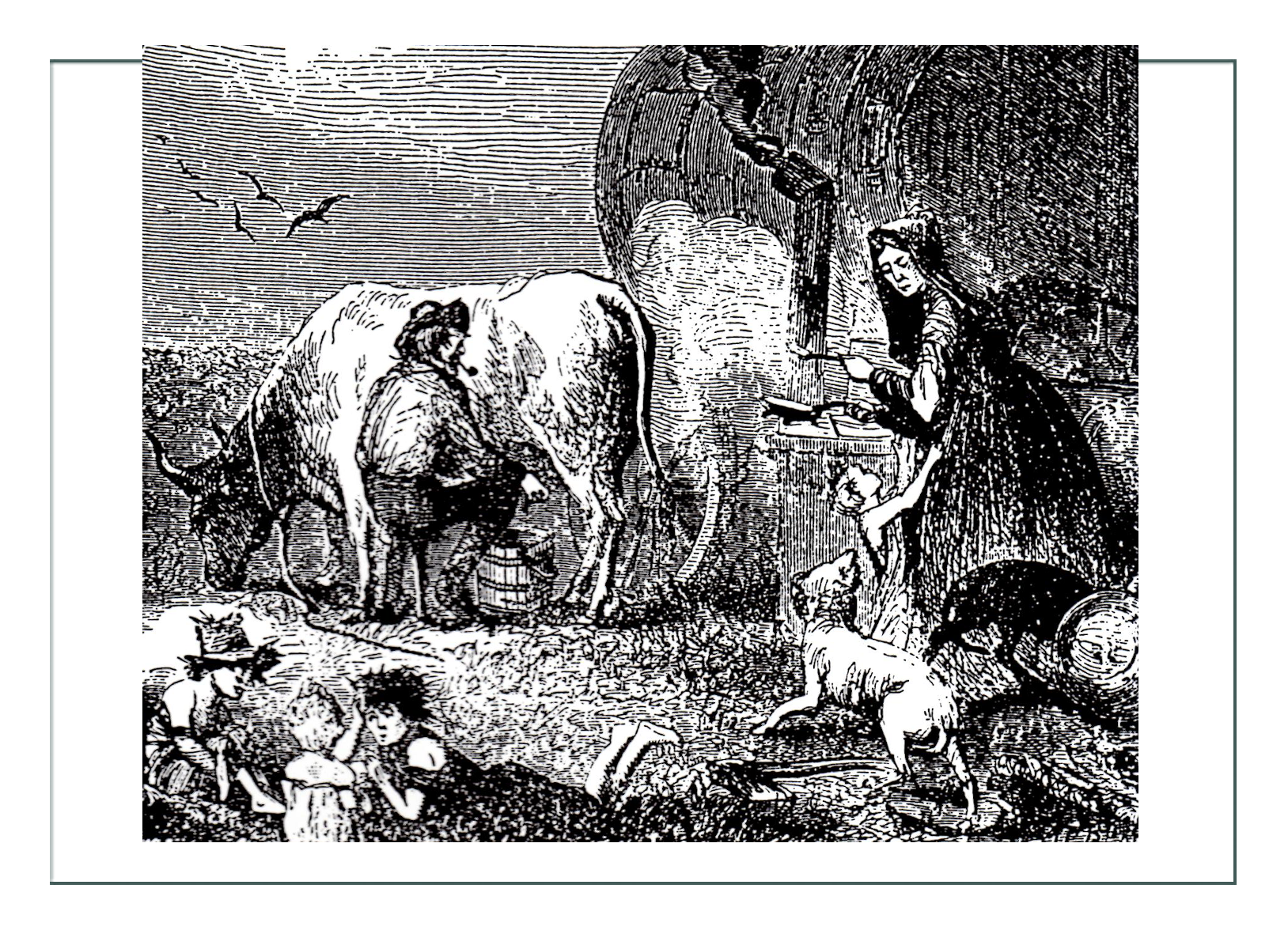

In the 1840’s, most of migration west was done in a wagon. From 1856-1860, the large Mormon migration was done pulling handcarts; largely pulled by women.

Some women traveled independently without a husband and worked as trail cooks. Even women with just her own family had to do the cooking the whole trip. Many of these women had never cooked before, and especially not for large crowds, so that was a big learning curve.

There were many births and deaths on the trail. At the time it was common that a woman would be married by the age of 16. Many had never done the physical tasks required of them on the trail before, and it took its toll. In many situations, married women were traveling alone and had to do everything whether they knew how or had done it before because often their husbands went months ahead to prepare a homestead or stake a claim. In many cases they never found their husbands, or the husbands had died, or left to go mining. Women were very often left alone to find their way to the end, or to make it work.

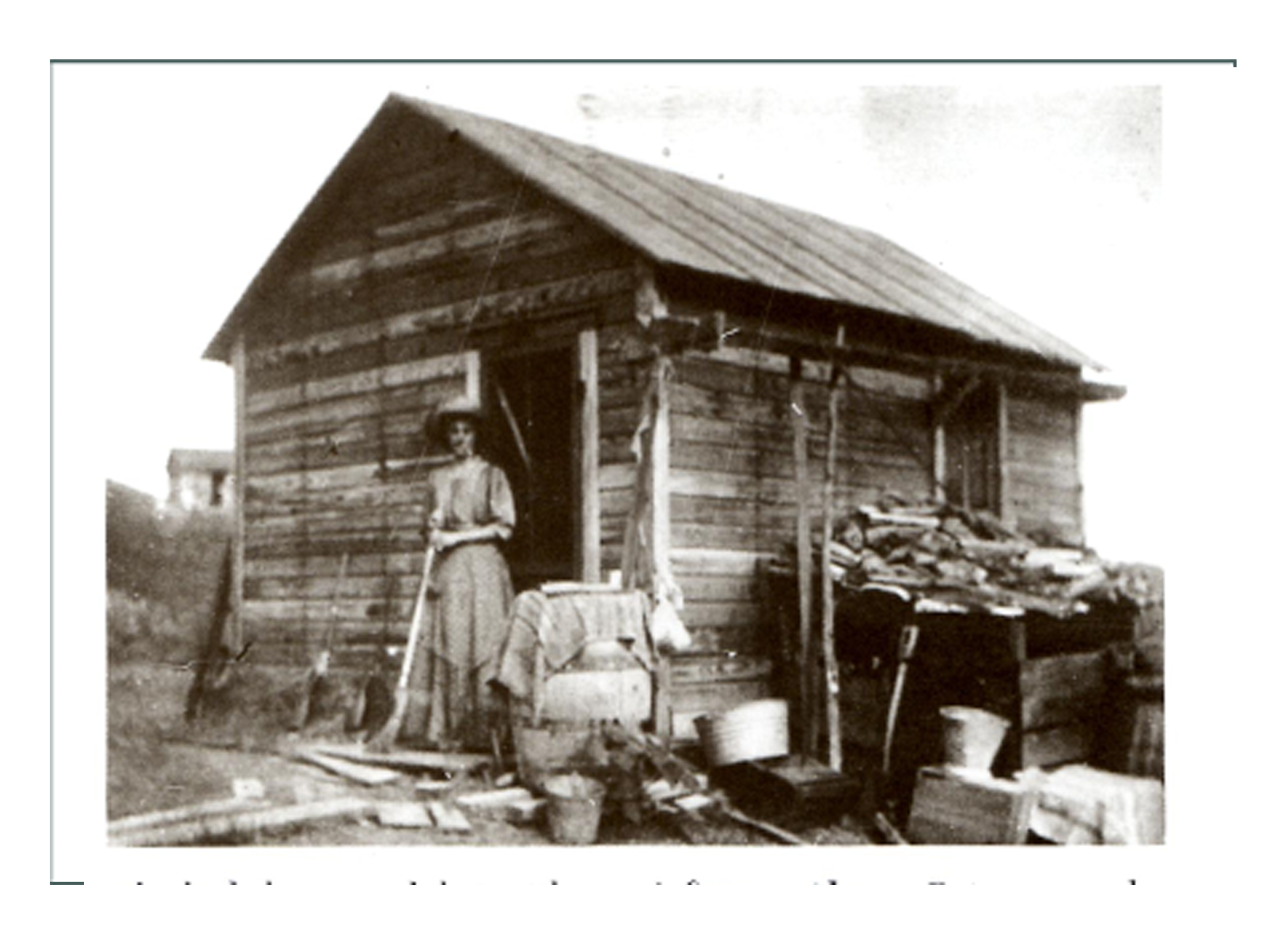

Once they got to their destination, they might be greeted by their man who had built a “soddy” or house out of sod in the side of a slope, or a tarpaper shack. That was all that was needed to establish a homestead. Often they would take apart their wagon and use the wood to build a shack, and put the canvas tarp over it as a roof until they could build something bigger. Often, nothing bigger was ever built.

Primary Concerns of the Western Settler

1. Water

Always primary and in their thoughts first and foremost was clean and sanitary water for people and animals to drink. Lucky ones found springs and running water with fresh creeks. Others dug wells. The wells might not find good water, so it was a dangerous gamble.

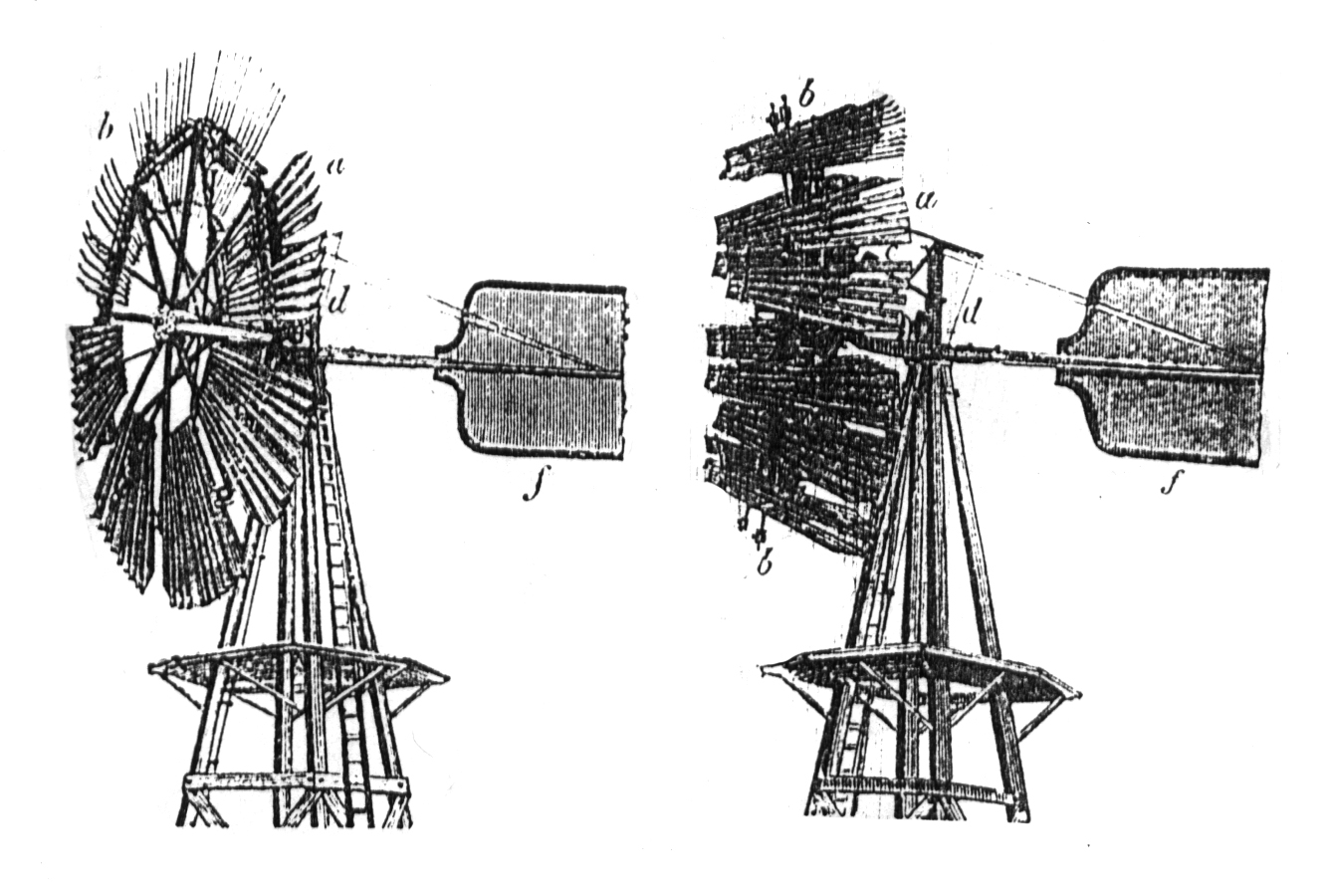

As time went on, wells were dug deeper, and water was transported. Most augemented whatever their water source with melting snow, or collection of rainwater in barrels. Later and in some regions windmills would be installed to pump the water out of the wells into tanks for stock. Many of those remain today in the west, and the windmill business was thriving by the 1860’s in places like Batavia, Illinois.

2. Waste Removal

In the beginning and along the trails, pioneers used fallen brush and downed tree trunks as their outhouses. There would be one location for men, and one for women. Inside the house or wagon, a chamber pot made of enameled or ceramic or an old lard tin would be used to remove body wastes.

In time, outhouses with holes dug in the ground downstream from the water source were installed away from the house. Some were very fancy with each member of the family having their own hole. There were public outhouses in town with up to 9 holes in them. Many of these “necessaries” were still used in rural areas of the west well into the 1940’s.

The real problem wasn’t so much where people were going to go, but where the waste went after that. Other than the holes, and especially in towns, most waste was dumped into rivers and streams. Towns had “honey wagons” to pick up the pots, and they dumped into the streams. Even years later when plumbing was installed, the plumbing ran right into the waterways. It would not be for many decades until waste was processed as we have it now in septic or processing plants.

3. Lighting

In the days on the trail, candles or campfires were the source of light. In the early settlements, home made candles of many types were continued to be used as the only source too. A “saucer lamp” was the most commonly used type, which was a twisted rag coated in lard. It was placed on a dish with various types of reflectors made out of metal. The dish would have melted lard on it too, which would burn down and continue burning on the dish.

Coon oil was a favorite for distant pioneers. In general stores, one could find pre made candles that had been shipped from the east. Gradually, kerosene and other flammables became available, and the various lamps and wick lights came into common use in western and rural areas.

The cycles of work and rest reflected the amount of light available. This meant there were many long, dark winters where they had to stay inside. It is no wonder many homesteaders found themselves with child soon after their first winter.

4. Building covering/insulation

Western climates could be harsh between wind, snow, heat, cold, and winter darkness. In addition, settlers had to build their homes to protect them from fire, rain, flood, insects, snakes, and animals like skunks, cougars, and bears.

On top of that, there was a human danger too. Cowboys and vagrants roamed the regions looking for work, or coming back from mines. There were people there just to make trouble; and those who had escaped the laws east to live free. In particular, there was a stigma against cowboys and a saying in the 1840’s that “no virtuous woman is safe near a cowboy.”

Travelers had heard all sorts of stories about Indians too, and were afraid. Settlers learned about those who lived in their specific area, and what was true or not true eventually. Diaries and journals noted that women learned how to identify what an Indian was wearing; such as if in war or daily dress. They also made note that a drunk Indian was more dangerous than a sober one.

On the Indian’s side, there were stories that made them afraid of the settlers too, and with good reason. With so few Anglo women in the West, it was common and acceptable practice for Anglo men to kidnap and rape Indian women.

Houses were vulnerable to all of the above, as they were built in the beginning of dirt and canvas. As time went on they built buildings of logs, straw, dirt, and manure. These became refined as time went on, and when the trains came around 1870, but in the 1840’s and 1850’s, building materials were limited.

Holes between logs were filled with cloth or paper. Old newspapers or posters were used to line the inside of walls or as wallpaper for decoration. A lucky pioneer would have brought or have shipped in a good wood burning stove for heat and cooking, but it was very rustic by today’s standards.

Eventually homes made of stone, brick, or imported woods were built by those who had become successful, but in the early days a simple log home with a wooden floor to keep out the animals was considered luxurious.

5. Boredom, Isolation, and a New Moral Order

Often when a woman arrived at her destination, the husband took off – to buy stock, to set up businesses, to share in a round up, to mine, or whatever. It was a very free time for men, who enjoyed the luxury a woman did not have in that he could leave the house and homestead to seek adventure or income.

Even if a man had gone in advance to set up, and the woman arrived at a built house and farm, it was still she who had to stay and run the house, stock, gardens, children, animals, and everything related to running a home: cooking, cleaning, washing, making soap, candles, heat, and taking care of emotional and medical needs of all involved. Except for children, she was often days away from the nearest neighbor, and all alone night and day.

The woman pioneer just needed someone to talk to once in a while. The only people she might see would be a low woman, or another rancher or farmer. The problem was, she brought her attitudes with her from the east, and would talk to a prostitute, and felt that a wealthy rancher was too snobby, so she also isolated herself in some ways.

She might have occupied herself through knitting, crochet or other domestic arts, but the concept of things like canning would not be introduced until the 1870’s. She had to work day to day just to survive, and had little time for luxuries, even if she had access to beads, yarn, or fabrics, which was rare.

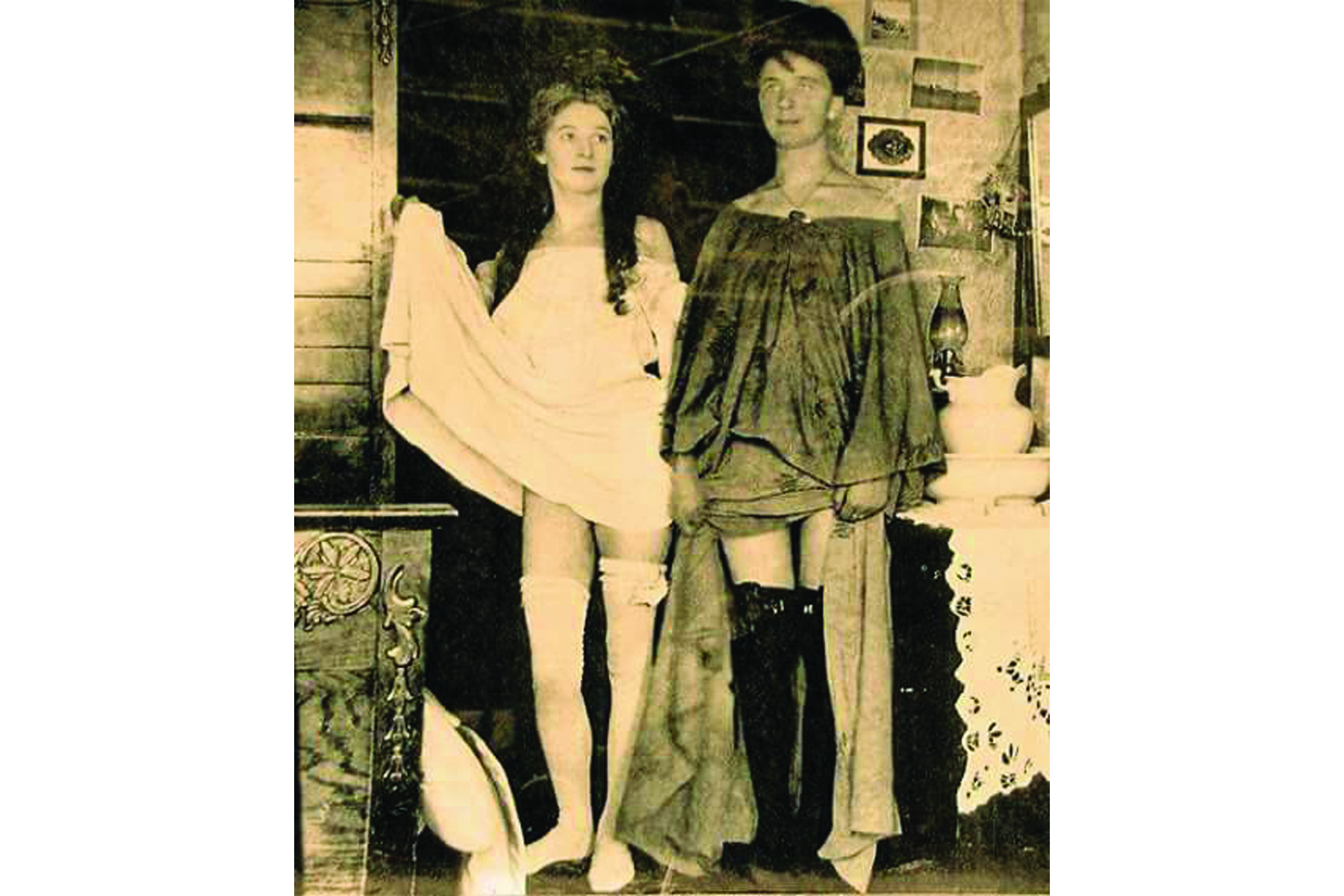

In 1851, in most places in the West, there were no churches, schools, papers, lecturers, concerts, balls, dances, picnics, rides, or any of the simple social activities pioneers had enjoyed where they came from. This led to a whole new culture and ethical/moral system which was much more relaxed. In other words, they adapted to the situation by creating new societal structures.

A key problem was that there was no mother nor grandmother to pass along moral lessons or information. There was no one to assist in pregnancy or childbirth, or to advise on the values of marriage or how to work within relationships as there had been when living with the extended family east. One must recall they had no communication methods to reach those people either: no phones, telegraph, mail, nor even a neighbor to pass word along. Women were totally on their own to come up with their own solutions. Once in a while they could send a letter if they were near a town. The only way they could share something like news of a birth was to send a photo of the child months later.

So were men free to create their own value and moral systems. The Mormon religion at the time had come West to practice their belief in plural marriages – a man having more than one wife.

“Common law” marriages were abundant. Many of these were Anglo men with Indian or Spanish/Mexican women. The men would leave the women years later when they met an Anglo woman. There were many different legal arrangements, including just moving in with a woman without marriage. With no towns or preachers around, there was no choice many times.

6. Keeping Children Safe, & Health Issues

With the man away or working, and the woman so busy every waking minute, keeping children safee was a difficult task. Abundant on wagon trains and in the west far away from towns or doctors, a child might easily contract typhoid, cholera, smallpox, or dysentary. This was one reason the local Tribes disliked the Anglos and missionaries who came, as these diseases destroyed many tribes.A child left for a minute on a homestead might be bitten by a snake, fall in the well, drown in the creek, run into a cougar or bear, or get a cut that would fester and kill them. Older children were tasked with watching younger ones, but those children had chores too.

Even young children had chores to do at their level. Children of pioneers in retrospect and in journals have noted they felt they had wonderful freedom as they could run “wild” across the plains and explore their worlds unheeded. They learned to ride from an early age and to take on responsibility and make their own decisions, and took pride in accomplishment and skills they felt they wouldn’t have learned growing up in a town or city.

On the other hand, children of the time noted they were also afraid much of the time, and that discipline was severe and sudden. The demands on their time and energies they felt could go to the abusive, such as a 3 year old having to haul water all day long. They summarized it was a 50/50 situation of good/bad.

The woman of the house had to care for the children and all the medical issues too. It became overwhelming sometimes. While children were considered a blessing and most pioneers wanted them for practical reasons of a good labor force as well as moral and religious reasons that they were a gift from God, it was also dangerous to have them all alone away from society or health care.

Information was scarce regarding birth control. There were “secret” ways shared between women such as sending through the mail for herbs. By 1873, they were “found out”, and it was made illegal to sell herbs for the purpose of preventing or aborting babies through the US Mail.

That left women with the option of counting the days of her cycle, or using a mixture of vaseline or cocoa butter with carbolic acid and rock salt to try to kill sperm. She would nurse as long as possible to delay her cycles. By the 1880’s, there were magazine ads (and magazines available to settlers) for insertions much like today’s diaphrams, which the prostitutes had been using in various forms prior to that.

There was not much talk nor information about how to deal with cramps or other related maladies. Midwives provided herbal potions for birth control, abortion, or birth but there was not much universal knowledge nor information available. Again, the woman was pretty much on her own to cope.

Finding Solutions – As they became Settled

The good

As trails and transportation improved, and towns were built and more people came, life got a little easier for the early pioneer woman. There were occasional visits by peddlers, who brought things like remedies for menstrual relief, and the current magazines like Godey’s Fashion and Peterson’s as well as catalogs.

Women knew about current fashion through these migratory salesmen. They would try to be fashionable, as by the 1860’s and 1870’s in most of the western regions social events had been organized. Bible meetings, dances, outdoor sleighrides, skiing, sledding, and gatherings had been organized between harvests and round ups. There were some schools and churches being built, or activities in the homes on a rotational basis.

Holidays started to be held together. At easter there might be a ranch community egg boil, at Christmas a gathering of candy pulling with locally played music.

People were bonded by adversity and mutual pride of accomplishment.

The bad

There was physical abuse and domestic violence among the pioneers. For most families, men respected woman’s contribution, but there alone in a wilderness of sorts, many men were free without the restraints of society and with a new moral compass, to take out their frustrations and fears on the women around them.

It was a patriarchal system in the West in the mid 19th century in America. The man legally owned ALL – including his wife and children. The woman pioneer had nothing at all. If her husband died, she would get nothing, not even her children who would be taken by others or sent to her husband’s extended family.

Usually the woman remained silent and tolerated physical or emotional attacks, because she knew she could not survive without a man in that situation. In the West, divorce was legal and allowed and was socially acceptable. The problem was the social stigma, and more importantly the religious sacrament that women believed in that “no man should put asunder” the sacrament of marriage. She internalized this, as well as would be cast out of any church organized or not should she divorce.

Sometimes an abused woman would rise up and defend herself successfully. Some did leave their husbands without divorcing them, and returned east to file the divorce. Some just left. On the frontier, a man with or without a formal and legal divorce might have a common law marriage with another woman.

Often the reason for conflict between man and woman pioneers was because the man decided he wanted to move again. In these situations often the woman would stay, and the man would move further west without a legal divorce.

The Single Woman Pioneer

It was very difficult for a single woman to succeed in both crossing the country and settling when she got to her destination. Some did it from the beginning on her own. Some did it with sisters. Others lost their men on the journey or somewhere in the process. Regardless of the reason or motivation, there were women who successfully emigrated and homesteaded all by themselves.

The challenge was that doing the tasks assigned a woman who had a husband was enough to fill every waking hour. A woman had to bear the children, make butter, sew, wash, cook, iron, bake, clean, gather eggs, care for stock, make soap and candles, and spin, card, weave, dye, and garden.

The single woman had to do all that (except maybe the children who were a “wash out” as they caused a lot of work, but also did a lot of work) PLUS what a man did – maintain the land, farm, ranch, stock, crops or herds, and manage helpers and run the business including marketing, sales, and transportation of goods.

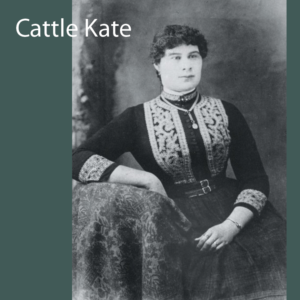

In places like South Dakota, to supplement income since they could not raise crops or beef as could a man/woman team, single women on top of running a homestead took jobs as domestics, teachers, assistants, companions, nannies, or other acceptable job for a woman at the time. A few “low women” like madams and prostitutes also maintained homesteads while running their businesses with the intent to leave their “low” jobs to become ranchers. Such as Ellen Watson “Cattle Nose Kate” tried to leave the brothel to be cattle ranchers, and helped establish law and policy following the Johnson County Wars in Wyoming.

In the diary of Elinore Stewart, a successful single woman homesteader in the 1840’s, she describes what it took to do what she did:

“For the single woman.. temperament has much to do with success… persons afraid of coyotes and work and lonliness had better let ranching alone. At the same time, any woman who can stand her own company, can see the beaut of the sunset, loves growing things, and is willing to put in as much time at hard labor as at a washtub… will succeed; will have independence, plenty to eat all the time, and a home of her own in the end.”

Some single women who pioneered West exceeded norms of the day and “bands of propriety” by running mines, saloons, gambling houses (or became gamblers), became cowboys, joined Wild West shows, became outlaws or prostitutes. Some were involved in human trafficking of prostitutes.

There were professional women who went west, notably teachers who started universities by the 1870’s. In 1847 a group of nuns lead by Catharine Beecher and Mary Lyon who were graduates of seminary and Catholic missionaries, set up an educational board for the Catholic church in order to train teachers for frontier regions. In 1851 the Cherokee Tribe established the first higher educational center west of the Mississippi for women.

Female physicians, shunned east of the Mississippi, started to come the the West in the 1870’s. Women lawyers came in the 1880’s.

In 1867, Mary Eckert, a professional photographer traveled through the Montana Territory taking portraits of other pioneers. There were other painters and artists traveling in the territories too.

There were volunteers throughout who helped fund, found, and build hospitals, schools, libraries, and churches. In 1863 Sarah Yesler, the wife of one of the men who founded the city of Seattle, WA, set up a program to bring “good women” to the West. Most who came were Civil War widows. There were also activists who were women who were fighting racism, class disparity, and abuse of laborers.

By 1869, when the transcontinental train track was completed, female pioneers of every type would arrive and settle in the West. They would follow the literal and figurative trails blazed by the women who came before them.

Click here to go to Jessica’s Fashion History page (next)

Click here to go to Jessica’s Design Development page

Click here to go to Jessica’s Main page with the Finished project