How World Fashion Ideals were Applied in the “New World”

How World Fashion Ideals were Applied in the “New World”

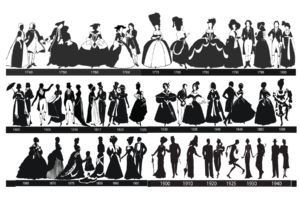

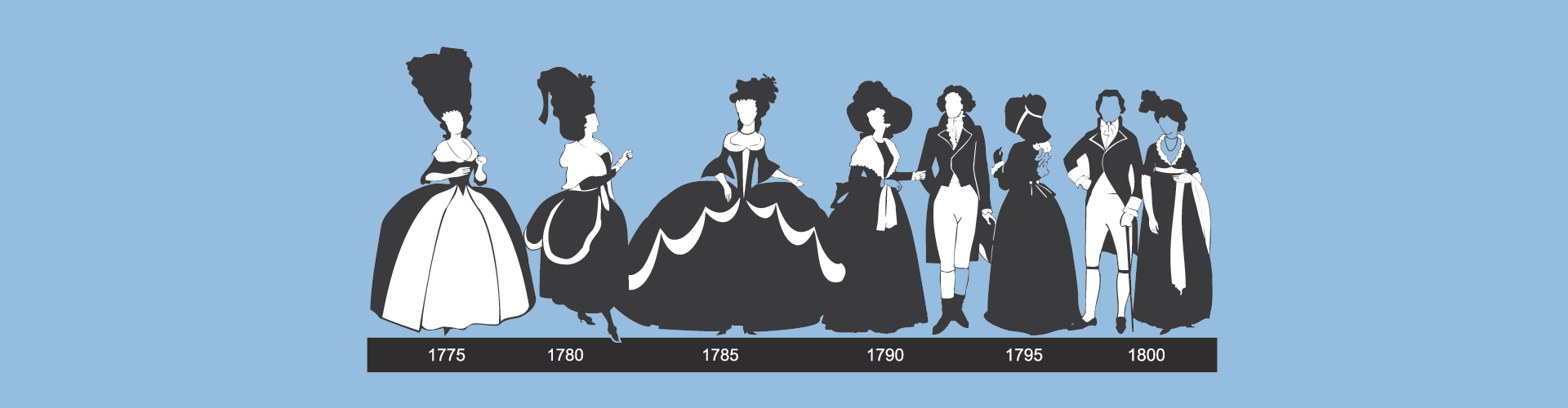

A silhouette is the recognizable shape of fashion as it changes

Fashion depends on what people know, can get, can do, afford, and want. A Silhouette is the recognizable shape of fashion as it changes. In the American Colonies, it was the Silhouette established by the Europeans, that was shaped and adjusted to fit the needs and tastes of women of the “New World” who had come from all over the world, bringing diverse and changing cultures and attitudes that would eventually merge into uniquely “American” fashion.

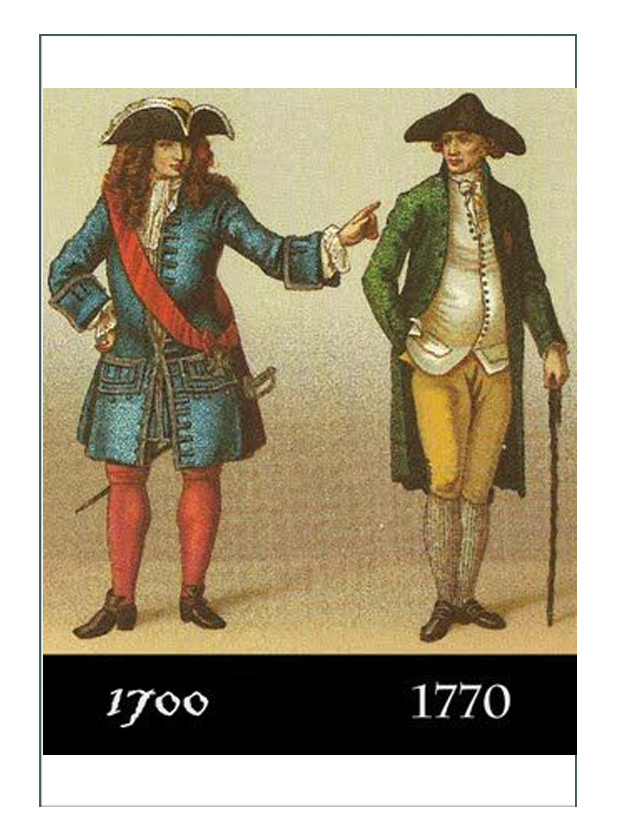

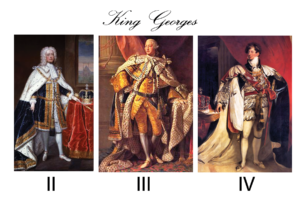

Most of the 18th century (years 1700-1800) was called the “Georgian Fashion Era” around the world, named after 3 King Georges of England. Because the United States was not yet created until after the Revolutionary War, the area that would become America was called the Colonies. When talking specifically about fashion in the geographical region that would become the United States, the “Georgian Era” was also called the “Colonial Fashion Era”.

The 1770-1790 approximate period covering the War was known as the “Late Colonial Fashion Period”. As with fashion today, there was no exact line that was crossed saying when one Era started and another began. Some women liked to keep their favorite clothing and wore it long after it went out of style, while others wanted to be right on top of what was new and fashionable.

The era was called “Georgian” around the world, but in what would become America, it was also called “Colonial”

Fabrics & Dyes

Cotton broadcloth is used today for “no iron” shirts

Fabrics were becoming cheap and available in Europe with the creation of factories, and these items were quickly shipped to the Colonies. The French and the English had led fashion trends for the world for centuries, but in 1775, Colonists started to give ideas to the Europeans. News of the North American West with its beavers, furs, and backwoodsmen affected European fashion.

Beaver fur from North America became a favorite of the French & English who wore it in their wars like this French military bicorne beaver hat (left): Napoleon Bonaparte’s signature bicorne (right) was shot off his head in 1807 during a battle with Russia

Beaver fur from North America became a favorite of the French & English who wore it in their wars like this French military bicorne beaver hat (left): Napoleon Bonaparte’s signature bicorne (right) was shot off his head in 1807 during a battle with Russia

Colonials in places far away from the seaport cities used more simple, natural, and plain fabrics and designs than people on the east coast. Even with the vast trade systems from around the world, these remote settlers couldn’t get a lot of the heavily ornamented or fancy things from across the ocean into the backwoods. The simpler clothing which focused on “function first” suited their lifestyles.

“Broadcloth” became the “every day” fabric across new America. It was a simple very tight weave with a smooth and flat surface that was durable and easy to sew. It could be made of different materials that could be found in the Colonies such as flax or wool. It was strong enough to be used over and over in remaking garments.

Cotton clothing & fabric had to be brought to the Colonies on specially outfitted cotton ships before 1800

Cotton clothing & fabric had to be brought to the Colonies on specially outfitted cotton ships before 1800

There were English ships coming and going between India and the Colonies, so Colonial women could get lovely fabrics. Trade with some Asian countries and places like Holland and Spain made other special fabrics, laces, trims, and finished clothing available to those who could afford them. China and its lovely silk fabrics was not yet open to trade with the Colonies.

People who had money got silks or cotton from India, because the Colonies did not grow or process much cotton yet. The special worm that spun silk would not grow on North America. India had that special silk worm in a special area that made them the only source of that kind of silk in the world.

18th century silk fabric from India was much thicker and lighter in weight than anything we have today. It made the shape of the gowns stiffer so they could be very big but not too heavy. The 1770’s silks made a special sound when a woman walked in her skirts that was notable of the Era.

India, which was under British rule in the 1770’s, also had special dye processes for cotton and provided the many beautiful floral designs that are now notable of the Colonial Era.

Trade with Indian made possible the import of beautiful florals printed on cotton and silk available to the Colonists. These designs are now notable of the era. Patterns became more delicate and detailed as printing processes & fabrics improved

The new America would become the leading producer of cotton by 1820, but in the late 1700’s, while it was being grown on southern plantations, it was still experimental there. There were few processing plants, so the making the cotton into fabric in the Colonies was costly. Most 1770’s Colonial homemade clothing was therefore made of wool, flax, or linen which could be grown locally.

The indigo plant which grew naturally in Eastern Asia, India, and Peru, was transplanted to England & used for the favorite blue/green color of the Colonial Fashion Era. By the 1860’s it was produced in America for Civil War uniforms

Colonial people could buy nice fabrics from places all over Europe like England, Holland, Portugal, Spain, and France. These countries had their own unique materials, designs, methods, and dyes such as the making of “plaids” in Scotland that the Colonists bought.

European countries, and especially England, had brought the artistic, chemical, and manufacturing methods from other places like the West Indies and Africa. They were trying to grow plants to make special dyes with some success, but historians say their art and science was never quite as good as that in the places of the plant or art’s origin.

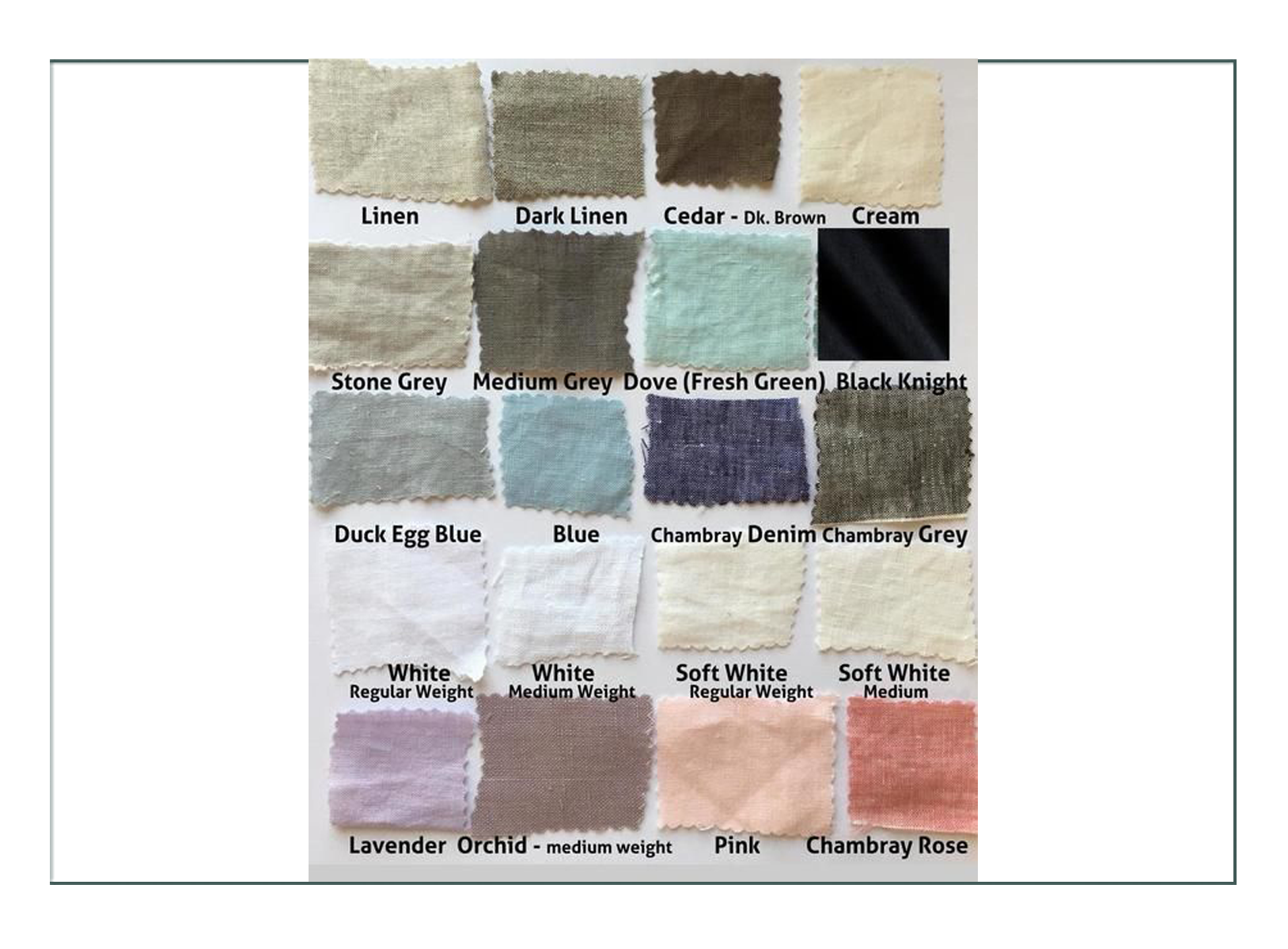

Colors from natural sources like berries and bark dyed onto natural fabrics like these linen samples are subdued and look like nature

Dyes produced in the Colonies were from natural sources too, like berries for pinks and blues. Sticks, twigs, walnuts, and nutshells made browns. Many plants, mosses, and bugs were used to make greens. There was a favorite orange/red color that came from an insect, although it had to come on a ship from an island so was hard to get.

“Red Dye No. 2” which is used in food today comes from a female insect which lives on cactus in southern areas of today’s U.S. and Mexico. It has been a favorite dye for orange/reds for centuries. (Right: botanicals like the center of the saffron flower are used innovatively, in this case for yellow/gold/oranges)

Indigo, which made the deep blue/greens of military coats (like blue jeans) was being grown in the south with some success, although it didn’t flourish in the Colonies. The use of North American indigo was widespread, and that blue would be one of the favorites 100 years later during the Civil War.

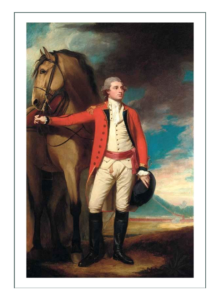

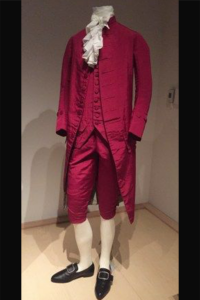

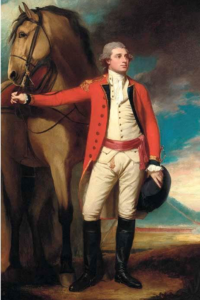

The actual “Redcoat” military uniform of the British Counsel to America 1794 (left), & Major James Harelty’s at about the same time; both dyed from the cochineal insect

The bright reds and pinks were a favorite of both men and women colonists, and the British used the insect dye to make their military uniform “Redcoats”. Intense blue or purple other than the blue/green or purple/pink types of blues could only be found from rare sources outside of the Colonies, so only the very rich and European royalty wore certain blues and purples.

Only Estruscan royalty (left) wore the bright purple that is still reserved for Royals today like Queen Elizabeth II of England (right)

The favorite colors of Colonial women were the many pinks, browns, and a blue-green called “teal” plus the indigo blue. Synthetic dyes would not be invented until the 1850’s when a man accidentally invented “mauveine” while trying to find a cure for malaria. With a huge fashion industry in the 1870’s and a big interest in science at that time, most of the really bright and intense colors you see today were invented around that time, 100 years after the Revolutionary War. It was rare to have bright or intense colors in 1776 unless you were royalty.

Even main streets in big cities during the 1770’s were muddy like this modern day Colonial Williamsburg living history site

Fabrics

Linen

The fabric of choice for every day women of the 1770’s was linen. Linen acts much like cotton, but it is stiffer and has a shiny side to it, a rough feel, and has a more open weave. Both cotton and linen let air flow in and out, so they are very comfortable to wear and work in, and easy to clean.

People did not know about germs yet in the 1770’s. It was only in the Late Colonial/Georgian period people figured out they should wash their clothes and themselves regularly to prevent sickness. A new type of detergent similar to today’s bleach was being used. Because it turned everything white, white became the most popular color for things that would be worn a lot or touch the ground.

Roads in the Colonies were muddy. Even in dry places, dust would get dresses very dirty. Women worked hard and had no air conditioners or electric fans. Even women of wealth and royalty did work, and they would get sweaty. The natural fabrics and the design of their clothes kept them comfortable between washings. Only the bottom most layers would get sweaty and have to be cleaned often.

Europeans Followed Colonists

Europeans Followed Colonists

1776 American militia man (left); King George III at the same time (right)

There were philosophers in Europe who were teaching people to “simplify”, and the informal American styles and use of soft, comfortable to wear, natural fabrics appealed to people of England, France, Spain, and other countries. Because it was a time of abundance in both Europe and the Colonies, people had the luxury to think about what they were wearing, and to make choices.

The English had more leisure time than Colonists, and were generally outdoors more than other Europeans at the time. The English culture valued open spaces and physical activity, and was still predominantly agricultural.

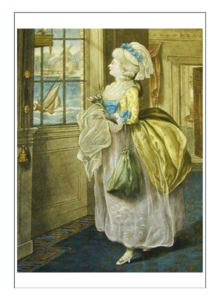

Simple walking clothing for Colonial (left), Englishwoman (center), Frenchwoman (right) illustrates how the French took a simple concept and made it complicated

French culture focused on indoor activities and Court life. English and French clothes reflected each one’s lifestyles of indoors or out. The French, however, were peeking at the English, who were peeking at the Colonists. The French especially liked the simple and rural type of clothing the English and Colonists were wearing.

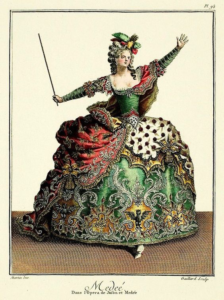

Europeans gave the Colonial ideas of simplicity with natural colors, natural fabrics, and “plainness” to their fashion designers to make them into new designs. The new French fashions of the mid 1770’s had the same shape, colors, and fabrics as the Colonist’s, but the French added fancy work, ornaments, trims, and “flashy” details. The French “Colonial Fashion” was not much like the Colonial’s “Colonial Fashion” by the time they got done.

French opera costume sketch 1774-75, supposedly based on Colonial fashion, strayed far from it

Style of the 1770’s would become simpler by the 1790’s, led by French designers who were peeking at the comfortable clothes of working people in the Colonies

“Regular people” around the world, those who worked or ran businesses or farmed and who were not royalty, were wearing more simple and comfortable clothes constructed from easier to make and cheaper to get fabrics. Through the 1770’s and into the 1790’s the French continued to build fashion to become excessive in design under the example of French Queen Marie Antoinette.

Creole women (right) embraced the loose, cool, cotton Gaulle style of Marie Antoinette of France(2 to left) in the Dominican by the 1790’s just because it made sense

When Marie finally embraced a new, soft, and feminine style called “Gaulle”, the French would swing back the other way to make the next fashion era, The “Regency Era” very simple. All the ornament and fuss of the “Georgian/Colonial Era” would disappear from the 1790’s to the 1890’s.

Colonists Followed Europeans

French King Louis XVI & Marie Antoinette his queen (left); same yet very different from a real gown from 1776 America

In the 1770’s, the French demanded their royalty must look very different from “regular people”, and the French King wanted those who had money to spend it all on French fashion which was made from French fabric, lace, trims, and notions. In 1775 the French Queen Marie Antoinette wore the highest hair ever on top of her head. Another woman, a friend of the King, Madame Pompadour, wore a sailing ship over a tall wig.

Madame Pompadour wore a ship on her head

Both women’s dresses became so wide and so huge they couldn’t fit through doors. Fashion dictated that breasts be pushed up and necklines go way down. There were never too many tassles, ruffles, fringes, laces, plumes, or artificial flowers for the French. Even the men in French Court wore elaborate wigs and had clothing covered in fancy trims and embroidery.

French fashion leaders, Queen Marie Antoinette (left), and Madame Pompadour (right) in Court ensembles

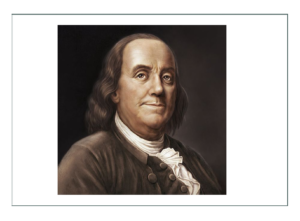

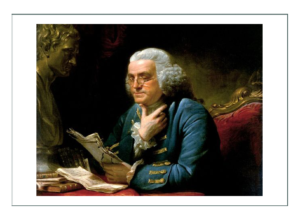

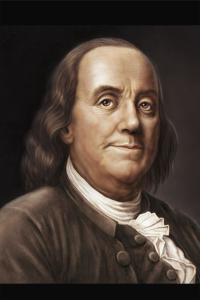

By the end of the Revolutionary War, however, with a change in power in France, the crazy French court costumes were replaced with very natural and very simple looks. Even hair, after Benjamin Franklin of America went to the French Court in his natural hair after forgetting his wig, became natural again. Colonists, by then calling themselves Americans, had been copying French fashion. The Americans along with the French and English pulled back to simpler and more comfortable styles in the 1790’s.

Benjamin Franklin (left) in natural hair 1767 & same year in his wig at Court in London, England (right)

Many Americans, particularly those with ties to the English before, during, and after the War, still wore the elaborate styles through the 1770’s. Women of middle and high class status continued to wear the elaborate French Court styles long past when they had gone out of fashion in Europe, although they backed off a bit from what the Queen of France was wearing.

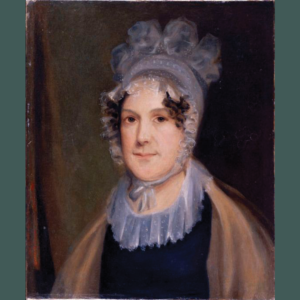

Queen Charlotte of England (left), Martha Jefferson late 1790’s, and First Lady Martha Washington (right) at age 58 in the mid 1770’s

Georgian & Colonial Fashion Specifics as Applied in the “New World”

Colonial clothing was known for its great diversity because there were people from royal governors to indentured servants and slaves and everyone in between living in what would become the United States before, during, and after the Revolutionary War. In the 1770’s upper classes kept up to date on what was in fashion in England and France from imported garments, letters, news from travelers, and dressmakers or tailors moving into the region.

Re-enactors at Colonial Williamsburg depict specific people including artisans, trades people, and those of all classes. It was a time of class distinction strictly directing what people wore and how they wore it.

Re-enactors at Colonial Williamsburg depict specific people including artisans, trades people, and those of all classes. It was a time of class distinction strictly directing what people wore and how they wore it.

Women and girls living in the Colonies got most of their ideas on what to wear from England. The English got their ideas from France. The French had fashion designers and royalty who came up with the ideas. French Court fashion led the way in determining what women around the world would wear. Regular women would take the ideas of French royalty, and make them into things they could afford, make, and wear while doing whatever it was they did.

People learned what was fashionable through letters, prints, and from travelers

A wealthy planter’s daughter in Virginia in 1775 for example, would have worn a gown of silk from India, underclothing made of linen from Holland, and shoes made in England which had gone through complex trades and a lengthy voyage across the ocean on a ship propelled by wind. A slave whose freedom depended on trade and commerce too would be wearing clothing made from inexpensive textiles imported just for his use such as a shirt of linen woven in northern Europe, woolen stockings from Scotland, or a knitted cap from Monmouth, England. Clothing and goods worn at the time came from all over the world, although most of the fashion ideas came from France.

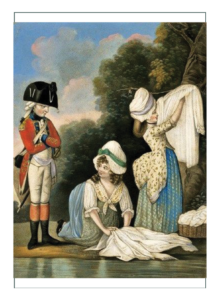

1770’s Laundry woman with skirts & sleeves hiked up: (left) Mrs. Grovesnor for the Queen, (right) for the British army

As with today’s people, men, women, and children of the Colonial fashion era valued comfort, warmth, and modesty. They also needed to meet the fashion “rules” of their society. If a woman did not wear the proper undergarments, or if a man did not have on a waistcoat in public, they were considered not dressed, so wearing the right thing was very important to both and women to fit into their communities.

Like people today, Colonists would give up comfort and modesty just to be fashionable; for example, through the 1700’s, women’s fashion said a woman should wear long sleeves and long skirts. Even though it would be easier to wear short sleeves and short skirts while doing something like laundry in a tub, the women wore the long ones anyway and just pushed their sleeves up or hike their skirts up.

Northern women (left) wore warm layers & heavy fabrics while southerners (right) wore cool silks and linens. What women of every shape & age wore had the most to do with where they lived and what they did for a living

Climate was the only thing that had a direct impact on whether people would give up wearing the latest fashion. In places like Virginia where it got very hot, all classes chose washable linen or cotton clothing instead of the many layers and fancy fabrics of northerners. In places like Richmond in the summer, men wore unlined coats and thin waistcoats that were more loosely fit than was fashionable at the time.

Women with money of the south preferred gowns made of “lustring”, a crisp light silk similar to silk taffeta, and some women even went without their stays (underwear) when at home when it got really hot out, but they would always put them on if they left the house.

Peddlers & storekeepers found a profitable market by going west to the frontiers to provide readymade goods to settlers that lived far away from towns & cities

Some upper class men ordered suits custom made to their measurements in lovely fabrics from London. Women could order fancy things like lace, shoes, stockings, cloaks, and even stays (the basic corset-like undergarment) ready-made through shipping trade.

Their gowns were usually made locally though by seamstresses or mantua-makers. Some women from the eastern Colonies made their own undergarments, but only in the frontier areas west was most clothing homemade entirely. On the frontier they even trapped furs, tanned hides, and made their own fabrics by weaving or knitting. Not long into American history did they need to do it all themselves, for traders and storekeepers early in Colonial history made it to the backcountry to make imported and readymade goods available to settlers and pioneers.

The Mantua-maker (seamstress) had to always dress in the latest “high fashion” even if it meant wearing thing beyond her means & impractical for what she was doing

One of the biggest questions that remains today about what people of the Colonies wore is how big people were, because looking at museum examples it seems both men and women were very small compared to those you see today on American streets.

Historic garments indicate women’s waists were between 21 1/2 to 34″ wearing stays (the basic undergarment around the torso which made them a bit larger than natural), with the average about 25″(compared to 30-36″ today), and bust lines averaged about 34″ (compared to 36-42″ today). Men were about 5′ 7 1/2″ tall on the average. Today scientists estimate the average man in America is 5’9″ tall.

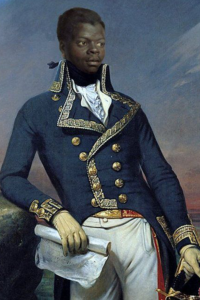

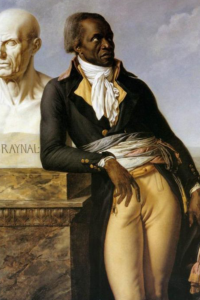

Toussant L’Overture in the 1770’s (right) & Don Barksdale in the 1940’s (left) were both considered tall for their times

Well Appointed

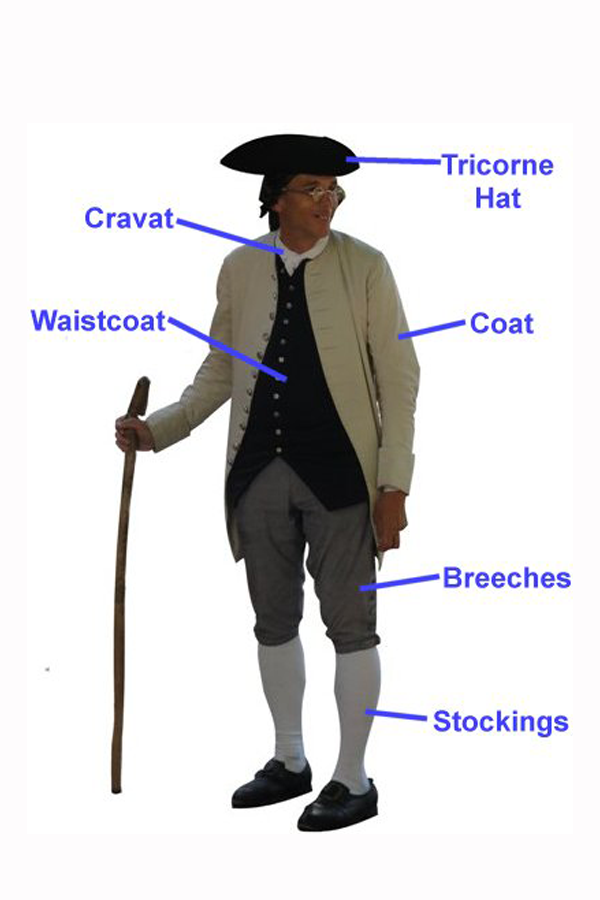

Men and boys during colonial times dressed differently than they do today. The clothing Colonials wore everyday would be considered hot, heavy, and uncomfortable now. Predominantly made of natural fabrics like linen, silk, wool, and a thick type of wool used in military uniforming that came from England called “Kerseymere”, most of what men wore was of fabric that weighed a lot.

Men and boys in order to be fashionable also wore many layers all the time. What they wore though really depended on the same as women: what they knew about, liked, could get, and could afford.

OUTERWEAR

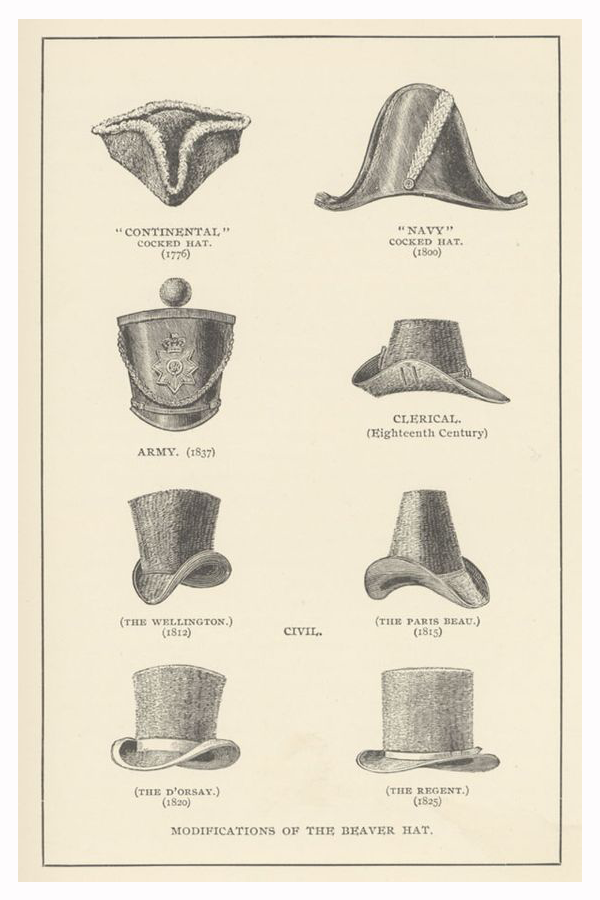

Hats

Starting at the top was a “Tricorne” hat. Colonial frontier trappers made a good living selling beaver fur around the world to be made into hats, as most military and fashionable hats in the 1770’s were made of wool or beaver. The Tricorne had 3 turned up parts that protected the person from the sun but also worked like gutters to send water away from his face. They were easy to carry in one hand too, and could easily be fit to stay nicely on the head and not blow off in a strong wind.

Over 3 decades, there were many men’s hats for specific occasions which marked their occupation (e.g. military or civilian), status, and location.

Wigs

Wigs were very popular for men in the middle of the 1700’s in particular. Wealthy men would wear giant wigs with long hair, curls, and ponytails. King Louis XIII of France had started the fashion trend 100 years earlier.

The first wigs were made from goat or horse hair and because they were never washed they smelled terrible, and attracted lice. To combat the smell and the bugs, the wearer would “powder” his wig using finely ground starch scented with lavender. Mice loved them.

John Hancock in his powdered wig, & modern actor in historically accurate one

No matter how old a man was or what his natural hair color or shape was, all the wigs looked the same and were white or gray. Wigs were associated with specific professionals like law or education, but most had no meaning at all. Ones closer to the end of the century were made of the hair of humans, horses, goats, and yaks. The style changed constantly, and stayed popular with all men until about 1800 when young men refused to wear them.

Coats

Banyans were based on the Asian kimono like clothing

A Banyan coat was a loose robe worn by men of wealth that were fashioned like a giant “T” and were worn when a man wanted to be comfortable or was in private. They were of patterned materials and were of all types of fabrics and materials so they could be cool or warm.

Caps

Sailors and Boy with Monmouth Caps; Patterns to make reproductions today

A Monmouth or Monmoth Cap was a small knitted cap worn by sailors and people who worked hard outdoors, especially in the northern Colonies and on open waters where it was cold. Knitting was a common pastime for sailors who sold the caps on the docks when they were ashore.

Cloaks

General Wolfe’s Field Cloak

Cloaks were also called “rockets”. Cloaks were worn by men, women, and children throughout the 18th century. They were usually circular if you laid them on the floor, and made of thick wool. A favorite color was scarlet, although there were often plaids, tan, black, and greens. Most were of natural colors, although many were dyed for military uniforming. They had a collar at the neck, an (optional) cape over the shoulders for extra protection from rain and snow, and hung down to the knee or below the knee.

John Singleton Copley in Frock and Waistcoat

Coats

A Coat or Frock Coat was the uppermost layer of a man’s “suit” which was worn over a waistcoat and breeches. Through the fashion era, the cut and name changed often. It was a fairly straight and loose garment with slight fullness at the knee with “skirts” falling into folds over the backside and the hips. By the 1770’s a “frock” was replacing the full-skirted coat though, and the term “Frock” was used to describe a narrower and straighter garment. Today “frock” general refers to a clergyman’s garment.

Pink was a favorite color for men’s waistcoats, and silk the favorite fashion for high status. Many were highly embellished and embroidered, while others were plain to show off quality fabrics

Pink was a favorite color for men’s waistcoats, and silk the favorite fashion for high status. Many were highly embellished and embroidered, while others were plain to show off quality fabrics

Waistcoats

The Waistcoat was worn under the Coat and over a Shirt. It was a tight fitting vest made from most any fabric. It could be plain or very decorated with lace, embroidery or tassels. A man was never seen in public without his waistcoat or he would be considered “undressed”. Waistcoats of the 1770’s were worn to the upper part of the thigh and had a “V” opening below the stomach. They were the most elaborate of all men’s clothing. When worn without a coat and for working, they were called “Jackets” instead of “Waistcoats” and were the outer layer.

NECKWEAR

Cravat

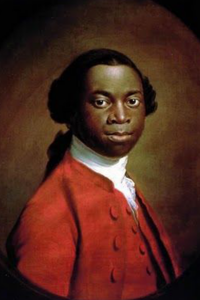

Olaudah Equiano, Abolitionist wearing a cravat

A Colonial man always wore some sort of neck cloth, whether they were trying to be in fashion or just working. The “cravat” was the most popular type. It was a narrow length of white linen that would have tassels, lace, fringe, or knots on the end. It was wrapped around the neck and loosely tied in front.

While fancy gentlemen used silk or fine fabrics, these were most often made from “dirty” linen or plain cotton – always white or ivory and plain. They might be very long or just long enough to go around the neck 3 times as the minimum. For higher class there had to be a little fringe or trim at the ends, but not for lower class. Fancy ones had finished edges, but most were just raw material, or had a little hand hem. The trick was getting a square knot right in center front, although there were many acceptable ways to finish the tie with ends either tucked in or hanging down at various lengths.

Stock

Toussant L’Ouverture in military suit with Stock in the late 1790’s

A stock was the very most formal neckwear, worn for events requiring the height of fashion or in military uniforms. It was always of very fine white linen and had pleats that fit beneath the chin. Sometimes there was elaborate lace and ruffle down the front below the neck. For military it was of black leather or woven horsehair. For the clergy the white linen stock had bands added. All of these were buckled behind the neck of the wearer.

Kerchief

Neck handkerchiefs worn by drummers (with pink!)

Untied was socially inappropriate, but workers in field or forge would use their kerchiefs to wipe off sweat, insects, or other functional uses higher class men would consider vulgar

Untied was socially inappropriate, but workers in field or forge would use their kerchiefs to wipe off sweat, insects, or other functional uses higher class men would consider vulgar

A Neck handkerchief was an informal sort of neckwear worn while sporting, by workers, and by slaves. It was most often a square folded and tied around the neck, made of linen, cotton, or silk. They were white, plain colors, woven checks, stripes, or prints.

BASIC GARMENTS & UNDERGARMENTS

Shirt

Shirts were long and worn to sleep in; also wearing neck scarf

A shirt was usually the only underwear that a man would wear. It was usually made of white or unbleached natural colored linen fabric and was long all the way to cover the knees. A man’s best shirt for fancy wear had ruffles (“ruffs”) at the wrist and breast. A worker’s shirt would be of unbleached linen or small patterned checks or stripes. A man might wear his shirt to sleep in. All were made by hand completely, as sewing machines were not developed for mass production or home use yet.

Some shirts had the ruffles built into them, and some were plain. All had the same sleeve and neckline shape, and were typically of linen

Few examples of hunting shirts exist today

A Hunting Shirt meant a protective type of garment that was worn at first only in the North American frontiers and was similar to what European wagon masters or farmers at the time wore. It came to represent the Patriots during the Revolutionary War and different companies would have mottos such as “Liberty or Death” or the name of their military group embroidered on them.

While the Hunting Shirt is most associated with the expansion of the country west, it is historically correctly considered the “uniform” of the Patriots. Unfortunately very few examples survived to look at them, so the actual design is still unknown.

Breeches

The same kind of breeches were worn by men and boys starting at age 3-6, whenever the parents decided a boy was ready to “breech”

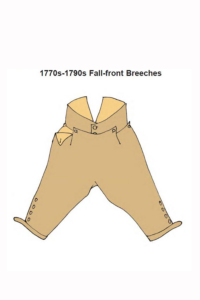

Breeches were pants that stopped just below the knee. They were the main lower body garment, and the design changed through the century. Early in the 1700’s breeches could barely be seen below the Waistcoat or Coat. Later they were more noticeable, especially because the coats were worn more open so that breeches could be seen in the front even if they weren’t long enough to be seen below the coat in the back.

“Fall Front” breeches had a flap and pockets. They buttoned at the waist and knee to allow a very tight fit that revealed the entire shape of the leg

There was a flap called a “fall front” in front at the waistband that buttoned up to be able to put the breeches on or take them off easily. Pockets were built alongside the flap.

By 1770 breeches became very tight and revealed the shape of the leg from knee to waist. They were worn by every man of every class and were made in silk, cotton, linen, wool, knit, and leather. The Founding Fathers wore breeches at the knee held up by buttons or drawstrings. Today they are still worn for horse riding events by both men and women.

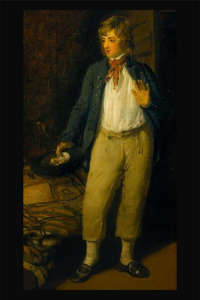

Trousers

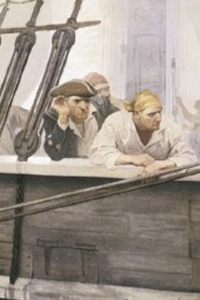

Sailor in Trousers and Neck Scarf

Trousers were what we call today pants that went all the way to the ankle, and were only worn by sailors and laborers. They were cut straight and stopped above the shoe at the ankle. They were almost always made of thick and durable linen.

Leg & Footwear

Leggings & Spatterdashes

Leggings were worn while working, in the military, or for sport (last are reproduction)

Leggings or Spatterdashes covered the lower leg of a man to keep him warm and protect his legs while working at jobs that things could hit him, or riding a horse. They were usually of thick wool or linen cloth or leather and were worn during sports, laboring, and in the military.

Stockings

The is the well put together fashionable ensemble of the mid 1770’s with typical white stockings and black shoes

Stockings covered the rest of the leg from knee to toe. They were worn by both men and women. The “knitting frame” (machine) was improved during the mid 1700’s so that handknitters were put out of business.

Fashionable stockings were made of silk or cotton and were white and sometimes were decorated with white or single solid colored embroidered patterns at the ankle called “clocks”. Worker’s stockings were made mostly of wool and some rough linen, with blue and gray the most common.

Shoes & Boots

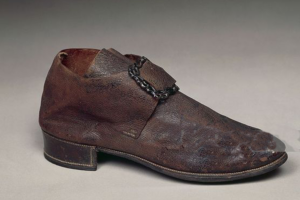

Black leather shoe reproductions (center) with historic buckles; authentic boots from mid-1700’s (center), Major Hartley in riding boots (last)

Shoes for both men and women were in great variety of styles and qualities. Low heeled shoes were considered fashionable and were of soft leather. Black was the most popular, and other colors were seen only once in a while. Buckles were the most commonly used way to keep them on, but many had ties.

There were many kinds of boots too, but they were not worn in public for social events, only for hunting, riding, or working. Boots were specific to the task at hand; e.g. riding, working, or military. Because “left and right” shoes had not been invented, boots and shoes could be very uncomfortable.

Women’s Shoes were similar, but often covered in matching fabric to the robe (gown). Children wore exactly the same as their parents.

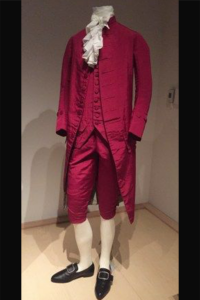

Suits

“4 suits in ditto, with or without ornament”

A suit is what we recognize today as a man’s 3 or 4-piece ensemble consisting of trouser/pant/breeches, shirt, waistcoat, and coat/jacket. The shorter waistcoat, breeches, and coat of 1774-76 became known as official “formal dress” when worn all together. To wear all pieces that matched was called “suit in ditto”, but more often a man would choose different waistcoats that did not match the coat and breeches, but coordinated with them.

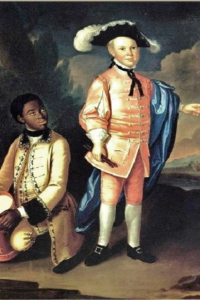

J.B. Belley about 1780 (1st portrait) and children in coordinated but unmatching Suits

Interesting Facts About Men’s Clothing

- Wealthy men padded their shoulders with rags or horsehair to look bigger

- When a boy turned 5 or 6 he would begin dressing exactly as his father

- Servants often wore blue

- The word “bigwig” comes from influential men wearing Big Wigs

- It was considered crazy for a man to cut his hair and for a woman to wear breeches

Even very young boys wore suits

Difference Between 1770’s Adult & Children’s Clothing

Families needed children to grow up fast and to do jobs to contribute, so their clothing was aimed at making the child capable and independent as fast as possible.

Leading Strings

When a child was little, their clothes fastened in the back and they had “guiding strings” or “lead strings” attached to the shoulders so parents could help a child learn to walk. Sometimes they were used to control a child who was running around.

Leading strings on both little boy’s & little girls’ dresses were popular early, but lost favor later in the 18th century

In the beginning of the 18th Century, babies were swaddled using stays and similar wrapping garments like what we now call “thundervests”. Even young children wore types of stays because the parents thought it would make them braver and more independent.

Through the 18th century those kinds of things were discarded in favor of dressing children from a very young age to look like their parents. Girls wore dresses with bodices much like their mothers, but sometimes they still had leading strings on a girl’s dress as a symbol of youth that she wasn’t a woman yet.

Both boys and girls wore stays, especially when dressed up because the parents thought they made good posture and supported their backs. Not all children, especially those of the labor class wore them though.

The royal family of Austria dressed the children the same as adults’ Court Fashion

By 1760 there was a philosophical movement for children to wear less restrictive clothing, Girls wore “frocks” with sashes. Boys wore suits with long trousers rather than knee breeches almost 20 years before men would change to the longer version. When a boy went from skirts to short pants sometime between the age of 3 and 6, it was called “breeching” and was an important step to becoming a man.

Young girls grew up fast regardless of their class, and dressed exactly the same as their mothers, also regardless of class

Pirate or Gentleman?

This is a wedding on a pirate ship. The year is mid-1770’s. Status is middle class, but it’s a wedding! The groom would wear his very finest which means full ensemble: shirt, stockings, shoes, breeches, waistcoat, wig, hat, frock coat.

The only difference between a pirate and a gentleman; boy or man was the quality of fabric, trim, fit, and wear.

These are our favorites from research which would meet the criteria for a groom who is a “little bit of both”. On the next page we will look at more specifics in the design.

Click here to go to Sam’s Design Development Page (next)

Click here to go to Sam’s Main Page with the Finished Project