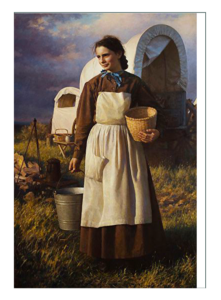

Jessica Wooten, 1849 Merchant Trader on the Lander, WY Trail

Jessica first contacted us to buy reproduction fabric we had on sale on this site for a project she was putting together on her own. She said she had “been bitten by the bug” to do historical costumed depictions when she was 12 years old and visited Conner Prairie in Indiana (see the 1836 project pages which was built for that historic living history farm).

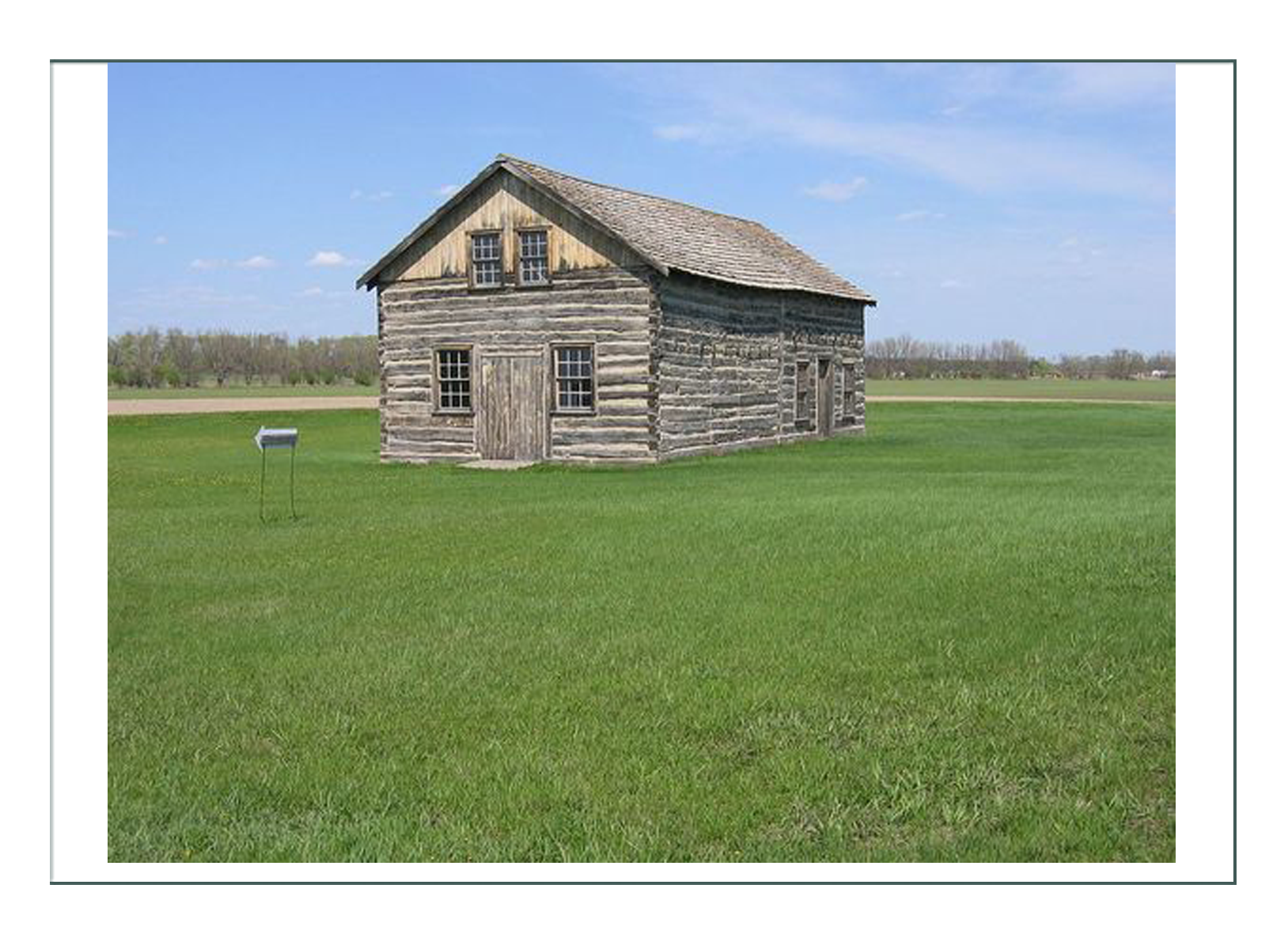

Settling at last in the area of Lander, Wyoming, she felt it was time to realize her dreams. She wanted to participate in the historical events around the Lander Trail, The Mountain Man Rendezvous, gatherings, parades, and other historical activities that are very popular in the area. Working in an 1888 flour mill turned boutique hotel, also spurred on her interest in learning and teaching more about the local history.

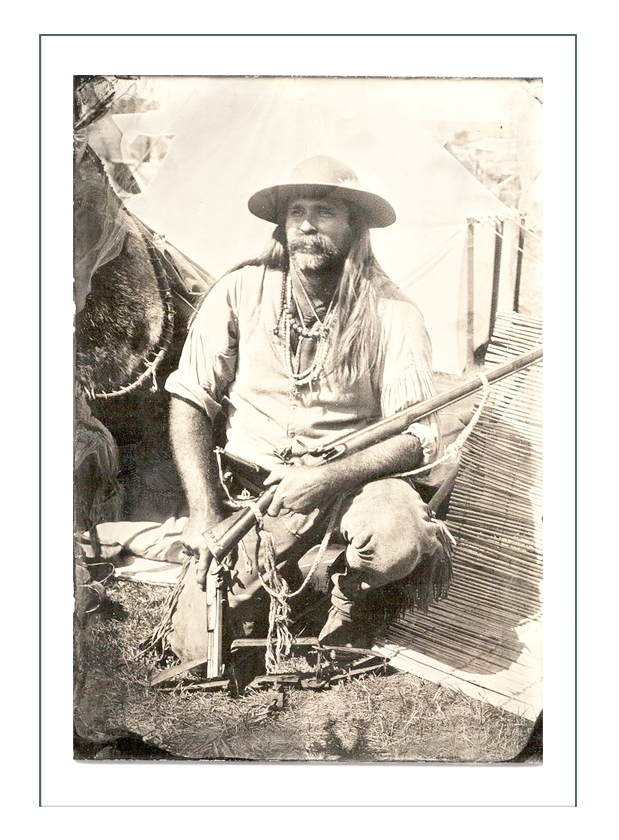

Lander today has a great museum about the settlement of the area; focused on the mountain men and trappers of the 1820’s to 1840’s who had worked compatibly with the local Indian Nations, and who had given the names to the mountains such as the French “Tetons” (which we will not translate here, but will say they would wear a very large corset). Those were the first Anglo-Americans (including many Franco-Americans in that bunch). Rarely did they have women with them other than indigenous such as Shoshone and cousin Tribes, so depiction as early as 1840 of an Anglo-American might be tricky. We began our research to find an Euro-American depiction that would suit her needs, personalities, and a special project.

So Few Yet So Many choices

Jessica is going to join the Buffalo Gals! She will join us for events when possible, as most of the Gals live about 3 hours north in various parts of Wyoming, with performances focused on the Cody, Wyoming area. This will expand the Gals’ performance options to join Jessica in her events in the south, as well as some of the Gals who have been with storytelling groups in the Thermopolis area which is central to the state.

For this to work, her ensemble needs to fill a gap in the flow of the Gal’s upcoming shows, and also satisfy special educational topical programs such as on corsetry, occupations of women, emigration, westward expansion, and Wyoming specific women and their histories. Jessica wanted to fit in with the Mountain Man museum efforts which focus on the 1820 to ’40’s, but there weren’t many women involved of “decent repute” that we could find until at least 1840 in the region. Later we would find gold miners and homesteaders and many settlers by the mid 1850’s, but until the mid 1840’s, it was pretty much Shoshone, military, and trappers in that region.

In addition, when we set up a Gal, we try to make the depiction true to the Gal’s own character or dream or passion. Jessica, the daughter of the equivalent of today’s missionaries, and a rancher, was not sure when she approached the project, so this historical documentation is meant to help her with a decision.

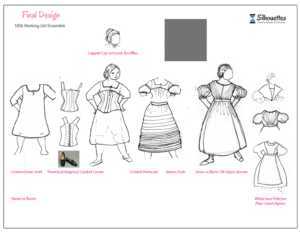

For this to work with the Gals’ shows, she needs to fit between an 1836 Mill Girl depiction which features transitional corded corset and petticoat, big sleeves, and lappet caps at the very crux of the Regency to Victorian era, and an 1856 Lumber Camp Cook depiction featuring the pre-crinoline era, flounced skirts, full cinching metal boned corset, and full Victorian ideology and fashion.

That did put us in the 1840’s, although later is better for purposes of more choices as there were more women there, and because the garments would be different than either of the other two outfits. Corset and petticoat in particular for a western or rural depiction in 1846-49 fits nicely between those of the 1836 and 1856 designs for storytelling.

We settled on 1846 because of the heavy use of the Lander Trail by then, plus the “Great Migration” of 1843 having reached the area. (How convenient!). Until 1878 there would be tension between Tribes and settlers, but that makes for good historical context.

Lander Trail History gives us a Clue

(for more detailed history, see Jessica’s Historical Context Page)

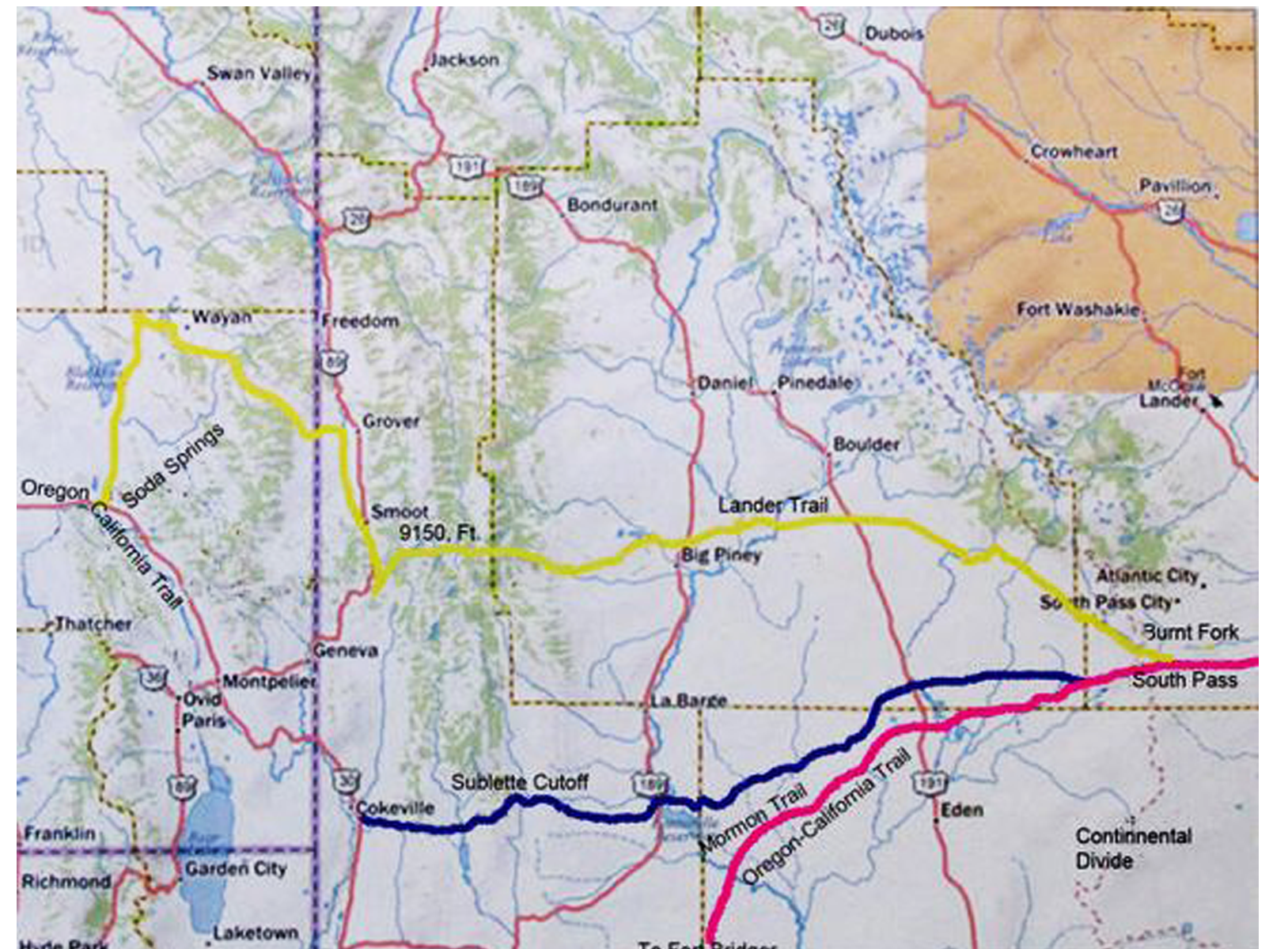

The Lander cutoff was established in 1857 as the first fully federally funded trail west of the Mississippi River. It was scouted and established by a military man, Lander, presumably as an alternate route to avoid the Mormon settlements, who were said to have attacked travelers.

The Lander Road departs the main trail at Burnt Ranch near South Pass, crosses the Continental Divide north of South Pass and reaches the Green River near the present town of Big Piney, Wyoming. From there the trail followed Big Piney Creek west before passing over the 8,800 feet Thompson Pass in the Wyoming Range. It then crosses over the Smith Fork of the Bear River before ascending and crossing another 8,200-foot pass on the Salt River Range of mountains and then descending into Star Valley. It exited the mountains near the present Smith Fork road about 6 miles (9.7 km) south of the town of Smoot.

Prior to that, the area was populated by the Shoshone and other Plains Tribes. Complete, the trail was 250 miles long and took 19 days to travel by wagon if there were no incidents. After the Transcontinental Railroad was completed in 1869, the trail was taken out of regular use, although vehicles traveled it as late as 1912.

Other military explorations and Indian relations made the area notable, although a gold mining boom in nearby South Pass caused population to burst and then recede when the gold played out.

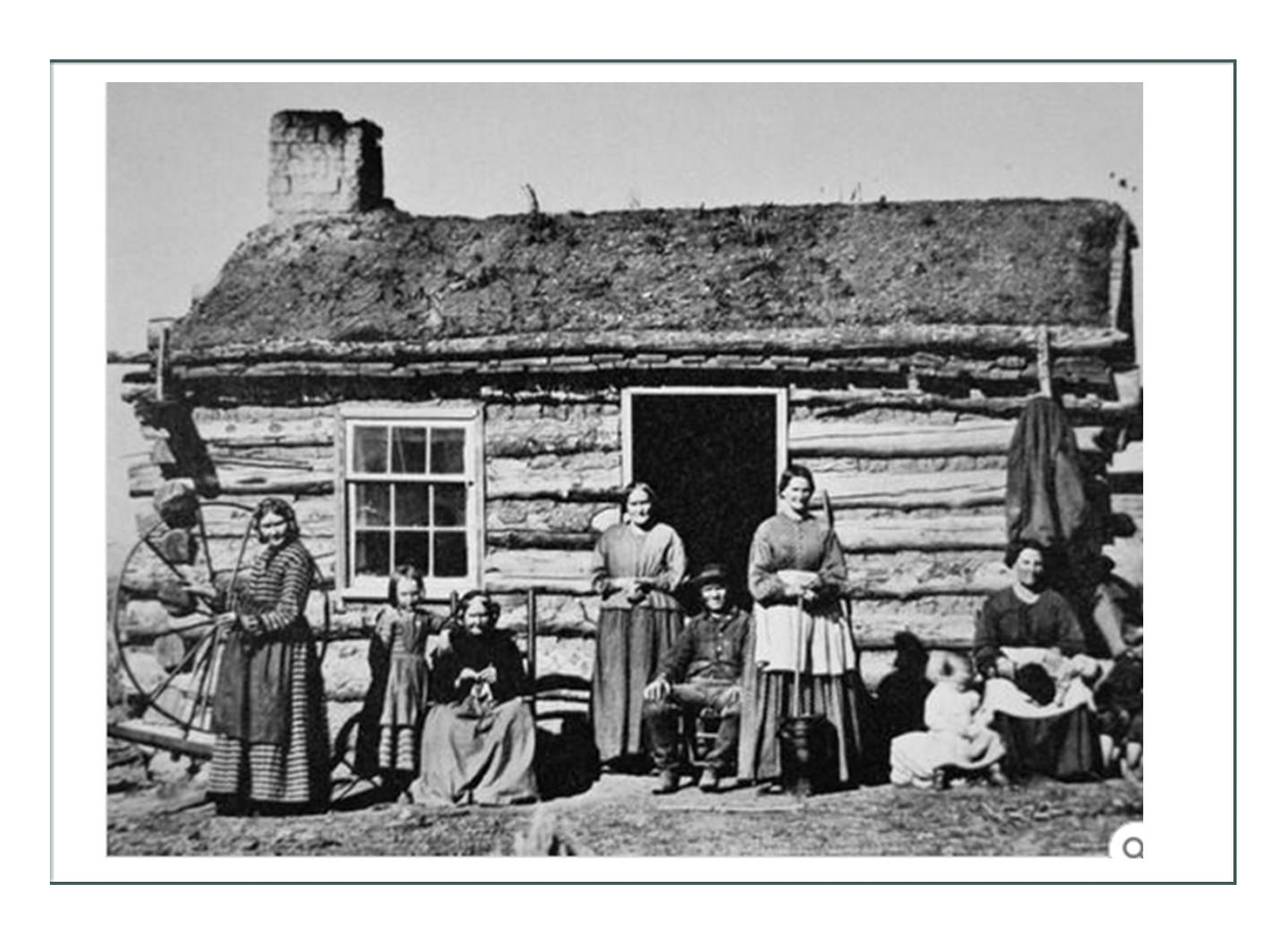

Euro-American (non-indigenous) settlement began for the most part at the end of the War Between the States in about 1865-67. Prior to that, and in the 1846 selected timeframe for this character depiction, it is most likely a Euro-American woman would have been:

- with a fur trapper – rare but not impossible backwoods woman

- with an exploration/expedition; predominantly military mapping or recording

- if military, would be a role such as wife, cook, laundress and kept at a nearby base

- more likely an early Euro-American emigrant off the trail following the military or with an interest in the Nations (studying, missionary to, subservient role to women)

One thing of note is the influence of Jim Bridger in the area at the time. The area to the north was off limits by Indian treaty until 1878 (the Cody, WY region), so these people except the trappers who worked with the Indians, would have stayed south of the Wind River Pass and south of what is now the Wind River Reservation.

The Oregon Trail, from which the Lander Trail was a northern spur, had its greatest and heaviest useage from 1846-–1869. In that time, the Oregon Trail and its many offshoots were used by about 400,000 settlers, farmers, miners, ranchers, and business owners and their families. The eastern half of the trail was also used by travelers on the California Trail (from 1843), Mormon Trail (from 1847), and Bozeman Trail (from 1863), before turning off to their separate destinations.

That puts this character at a key junction physically where trails merged and converged, and at the beginning of westward emigration. She would definietely be a newcomer to the area and one of the first women to settle, for whatever reason. It was in 1836 that the first emigrant wagon train left Independence, Missouri, so anything prior to that would have been as an individual, presumably with a man and on their own. They likely would not have been part of an organized group unless it was military.

There was no law at the time, and no city except the tribal communities, and the nearest trading post or European point of contact other than the trail itself would have been at Fort Laramie which provided goods to travelers and provided protection to the area from 1848-1855. That was many days’ ride east though, so anyone living in the area would have been quite independent.

The Green River Rendezvous at Big Piney in the 1830’s for fur trappers was the epitomy of social interaction by Euro-Americans. By the 1840’s, the fur trade had all but disappeared when the fashion for beaver hats died. It is unlikely she would have been with a fur trader; a trader or merchant perhaps, but not a fur trader.

A possible character would be the wife of a trader in a trading post if she was the type who got along well with the natives, and later the miners, military, and emigrants.

If a real person is desired, Jessie Ann Benton Fremont might be considered, as she traveled with her husband in mapping the Oregon Trail and regions. In this role, she was the recorder and documented the research for her husband as she traveled with him.

Fremont was the daughter of Missouri Senator Thomas Benton and the wife of military explorer, officer, and politician John C Fremont. She wrote many stories that were printed in popular magazines at the time as well as several books of historical value. Her writings supported the family. Her most popular was the memoirs of her husband about the times when the West was an exotic frontier.

If not this specific person, then a similar fictional character could be developed. Having a woman politically involved (through her husband as all were at the time though) would be appropriate to the “State of Equality” which in 1869 was the first in the world to give women the vote also.

Another feasible depiction for 1846 would be that of a missionary, on the way west, but stopping or staying in the Lander area. In 1834 the Dalles Methodist Mission was founded just east of Mount Hood on the Columbia River. In 1836 Henry Spalding and Marcus Whitman traveled west to establish the Whitman Mission near modern Walla Wall, Washington. Their wives, Narcissa Whitman and Eliza Spalding came with them.

Mrs. Whitman and Spalding became the first Euro-American women documented to have cross the Rocky Mountain. On their way, the party accompanied American fur traders going to an 1836 Rendezvous in Green River Wyoming (the Lander area) and then joined the Hudson’s Bay Company. They were the first to travel in wagons all the way to Fort Hall, after which they used pack animals. They were missionaries, and others joined them as husband and wife teams to settle the future states of Washington, Oregon, and Idaho. This spurred on the emigration that would follow with their success in travel and settlement.

Yet other missionaries were notable in spurring on the westward movement. Henry Spalding and his wife Eliza were prominent Presbyterian missionaries and Educators working with the Nez Perce in the Pacific Northwest. They traveled across the plains and the Rocky Mountains to get there to establish missions in Idaho and Washington. Their mission created the first wagon train on the Oregon Trail.

It is also possible this character could have been a part of the Great Migration of 1843 (more on this in the Historical Context pages):

In what was dubbed “The Great Migration of 1843” or the “Wagon Train of 1843”, when an estimated 700 to 1,000 emigrants left for Oregon. If an emigrant is chosen, the interpretation of the roles and relationships of women is to be developed using resources from diaries and records.

In the 1840s and 1850s, many thousands of emigrants traveling the Oregon Trail to California, Utah, and other western states passed through the North Platte and Sweetwater valleys and South Pass in central Wyoming. In the 1860s, as Indian troubles increased in the north, many emigrants preferred the more southerly Overland Trail through Bridger Pass. Until the railroad came, very few emigrants stayed in Wyoming.

The discovery of gold in 1867 at South Pass brought many immigrants to western Wyoming. A greater stimulus to settlement was the building of the transcontinental railroad in the late 1860s. Many Irish and Mexican laborers and Civil War veterans helped build the railway. Settlers from the Midwest followed the railroad into Wyoming, and built Cheyenne, Laramie, and other towns along the route. Any of these would be logical depictions.

Once they arrived at their new western home, women’s public role in building western communities and participating in the western economy gave them a greater authority than they had known back East. There was a “female frontier” that was distinct and different from that experienced by men. (in other words, it was the women who “settled” meaning built schools, churches, organizations, and government, especially in Wyoming (see history of Cheyenne for records of such).

By 1859 and 1860 the US Army had improved the trails for travel. Soon after, steamboats were able to take goods through the Panama Canal, and so did not use the trails as much. In 1860, the trails were good for stagecoaches, so the mode of transportation changed drastically from wagon trains. The Pony Express ran in 1860-61.

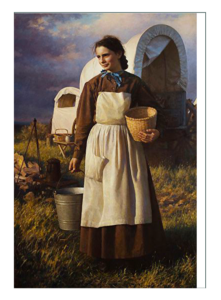

A logical interpretation would be an emigrant off shooting the trail onto the Lander trail for whatever reason: to map and record with her husband, minister to the Shoshone or work on relationships with them, or have some sort of job with the military; most likely running a trading post or outfitter, again, with her husband.

We decided this last, to run a trading post, was the most feasible given her interests and personality, that she wants to be with her husband (eliminating nuns and single homesteaders or missionaries), and that the actual location can be anywhere on or near the trail. She may change this as the project develops, but we will approach this as a “Trail Trader” for now, and will put addendum if she decides otherwise.

Silhouettes Tries a New Way of Working with Customers

We had been toying with the idea of selling “kits” to experienced seamstresses or those wanting to learn who have a passion for it, but less money, or are too far or too busy for fittings and measurements. This is a sort of “test run” for us working with Jessica who is experiences in building even more difficult Renaissance and other historical costumes.

She is including historical data and research here too; combined with what we find. We give her the summations and chronologies enclosed here, and she will build most of the garments. Jessica has decided she will build with our guidance and historical background:

- chemise

- open drawers

- petticoat

- dress (had a Fig Leaf pattern)

- boots

- accessories

Silhouettes will provide instruction and background on all above plus build for her:

- period correct corset

- correct bonnet

The development and selection of fabrics, notions, trims, buttons, construction methods, designs, and types of garments are discussed in the following sections. There will not be sketches of this project:

Click here to go to Jessica’s Historical Context Page (next)

Click here to go to Jessica’s Fashion History Page

Click here to go to Jessica’s Design Development Page

Continue below to see the final project

By Silhouettes:

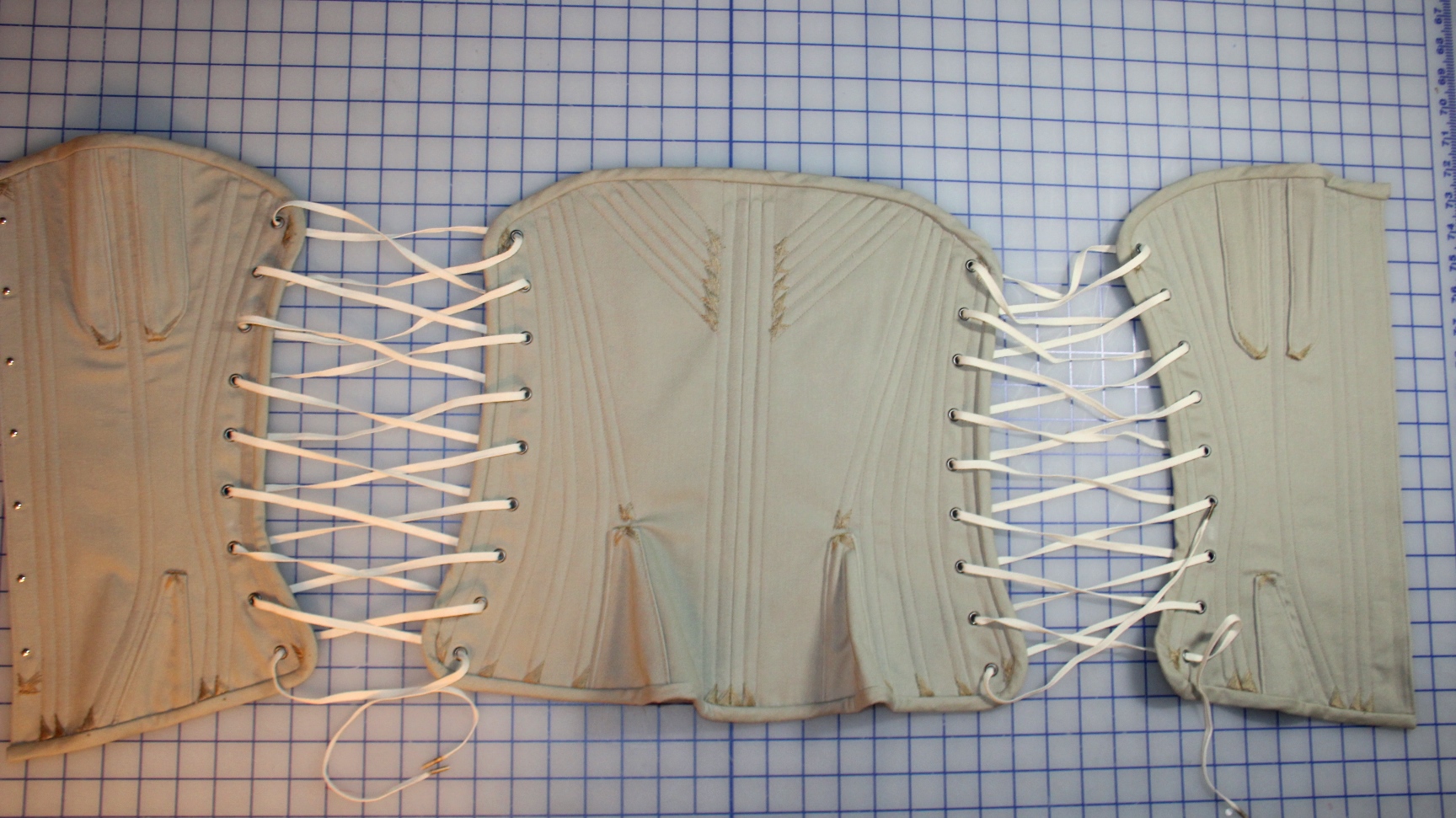

Corset

The design of the corset ended up being an interesting adventure as documented on Jessica’s Design Development pages. The result is this, a rural, tough, entirely functional, soft, comfortable, hybrid corset. It crosses the Regency corset with the early Victorian, and is what a woman away from civilization at the time might have worn while working.

Instead of a back lacing, front busk, this one has side lacing very much like those of the 18th century. While the busk is entirely functional, it is covered so the metal doesn’t get caught on anything, and it really mostly serves the purpose as a Regency wooden busk to keep the corset straight and to support the breasts a little bit; not as a closure. She will probably just throw it on over her head and lace up; lightly for working of riding and when pregnant; tightly to make a dress fit.

The green/gray brushed denim twill is a fabric that would have been available at the time, and the color consistent with rural too. It photographs here as gray, but it is somewhat a cross between a military khaki and a gray; we’ll call it green. The idea was to make it look well loved, worn, sweated in, and not so bright and shiny as her cousins might have worn in the east. It is slightly out of fashion for 1849, and is like a woman would keep her own, comfy, cozy favorite bra today to wear around the house. This is an “around the house” strictly functional, comfortable, adjustable corset, very similar to those that would be “invented” as part of sports corsets or in the Reform movement as predecessors to modern underwear.

We just “reformed” our western rural pioneer 40 years before everyone else. It’s really interesting because in the 1890’s, high fashion designers would build something like this and claim it was “new”.. so this corset is both ahead of its time and behind its time.

Below: lacing set for her normal size and shape:

Corset details:

Used as maternity:

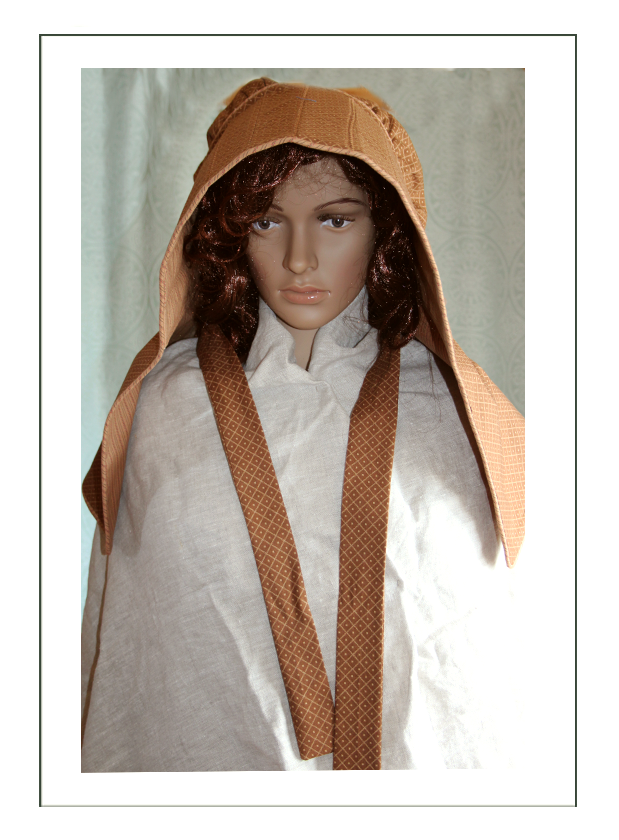

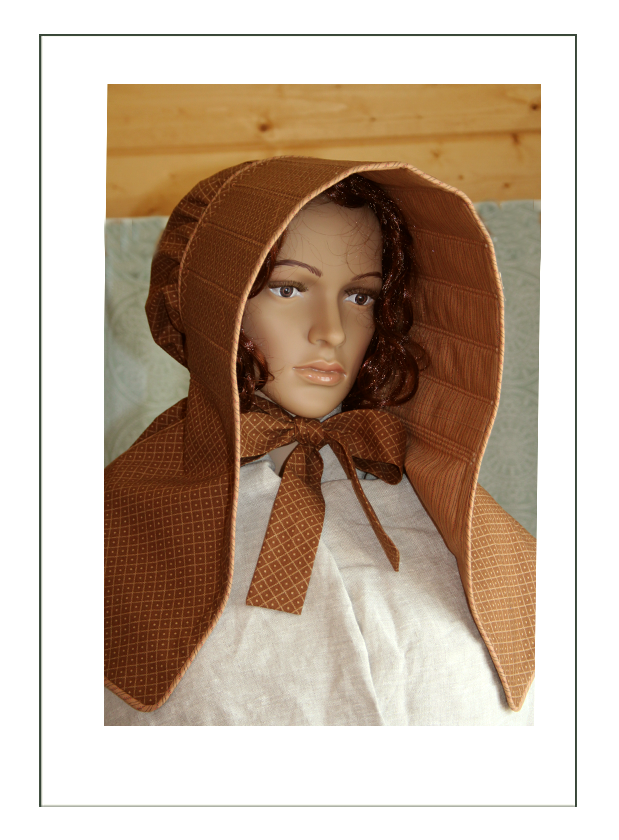

Slatted Prairie Bonnet

We are going to make two bonnets and let her choose. This first one she needs for working, the second for going to town. Both were necessary to protect a woman from the wind, sun, DUST, sweat in the eyes, and many other things that can come at you in southern Wyoming on a trail.

This bonnet is also actually based on the Regency style, which had evolved out of the 18th century mobcaps. All those eras have the same components in different proportions: brim, crown, and bavolet (curtain over back of neck). The high fashion bonnet of Regency had huge brim, cone shaped rigid crown, and little to no bavolet. The Fanchon of the 1860’s had short bavolet, rigid moderate sized brim, and a smaller cone shaped rigid crown. The working, rural, or western/pioneer bonnet was always a softer version of high fashion of the day, with modifications for the specific activity or geographic area.

A prairie bonnet of 1849 Wyoming, just as the rest of the ensemble, would be entirely functional. As with every garment, a woman might alter or adjust or add fancywork herself, so there would be some personalization and interest added, but it would be simple and low cost. In other words, you’re not going to find lots of lace, ribbon, flowers, or fancy embroidery on a bonnet designed to work out in the sun and wind where those would get in the way, fade, or deteriorate.

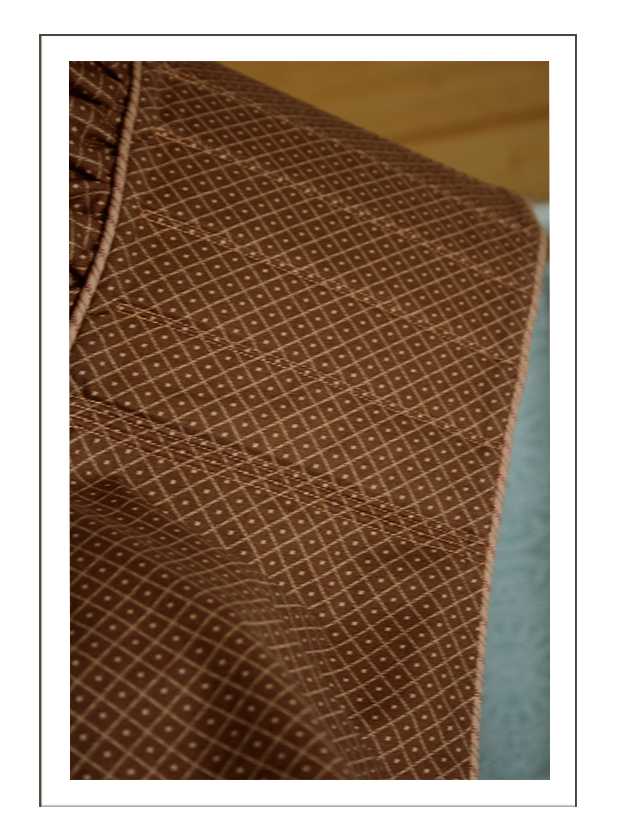

This bonnet is made from an historic pattern which was taken from an extant garment left in the estate of a woman who died in 1851. One can assume if she wore it to the end of her life, it was a mid to late 1840’s design. It is characteristic of all the rural/work bonnets of the mid 19th century in that it is of soft fabric construction, and features a large flexible brim, large soft and adjustable crown, and very long bavolet. It is clearly a design for a windy and sunny situation, where dust can get into the eyes, because the huge cone protects from wind.

The term “slat” refers to the strips of board inserted in the brim. When on the head, the slats are rigid to make a cone (so the brim doesn’t blow over and cover the face like a floppy hat would). When off the head, it lays flat across the back so it doesn’t flop around, and is easily stored. This was important for those on the Oregon and other trails in covered wagons, or who had limited storage in a little cabin. They could hang it flat against the wall, or slide it into a slot more easily than a soft bonnet because it was stiff like paper on a pad. We actually use illustration board for the slats. They might have used a sliver of wood, but that can cause tears, and is something difficult for us to find today; easy for them as they would have lots laying around.

This particular design is taken directly from the 1851 extant garment. The original was entirely done by hand with 10 stitches per inch. Ours, for the sake of time and cost, is all by machine but hand finished.

Unique to this bonnet as opposed to others of the time, and setting it apart as a western or pioneer design, is that the bavolet/curtain in back of the neck is not a separate piece. One notes modern patterns and most bonnets sold will either sew a seam for the bavolet, or will tack it on afterwards. It was usually a ruffle, and that design was more consistent with high fashion design with short 1-2″ bavolets.

This one has one long, continuous piece that is both bavolet and crown, or bavolet and brim. It is more an extension of those pieces. In our version, we had to seam the top of the brim because it wouldn’t fit on the yardage. We would guess that happened with real women of the 1840’s too, because you can get this out of one yard of 45″w fabric for the outer if you seam the top of the brim which nicely uses up all the fabric.

Piping/cording around the brim and at the junction of crown and brim is very pretty, but it is actually there to give stiffness to the front and around the head; “to add body” as they said in the 1840’s.

The lightweight and breathable hat might have to be interfaced otherwise. This allows delicate or thin fabrics to be used for summer weight bonnets which would not have fabric so heavy as to bend the slats. It also allowed the same design to be used as a fashion bonnet when made in silk with some fancywork and ornament, although adding flowers or medallions and such was rarely done even with a silk bonnet. More often you might find an origami type folding flower that could be sewn flush to the side of the crown for ornament.

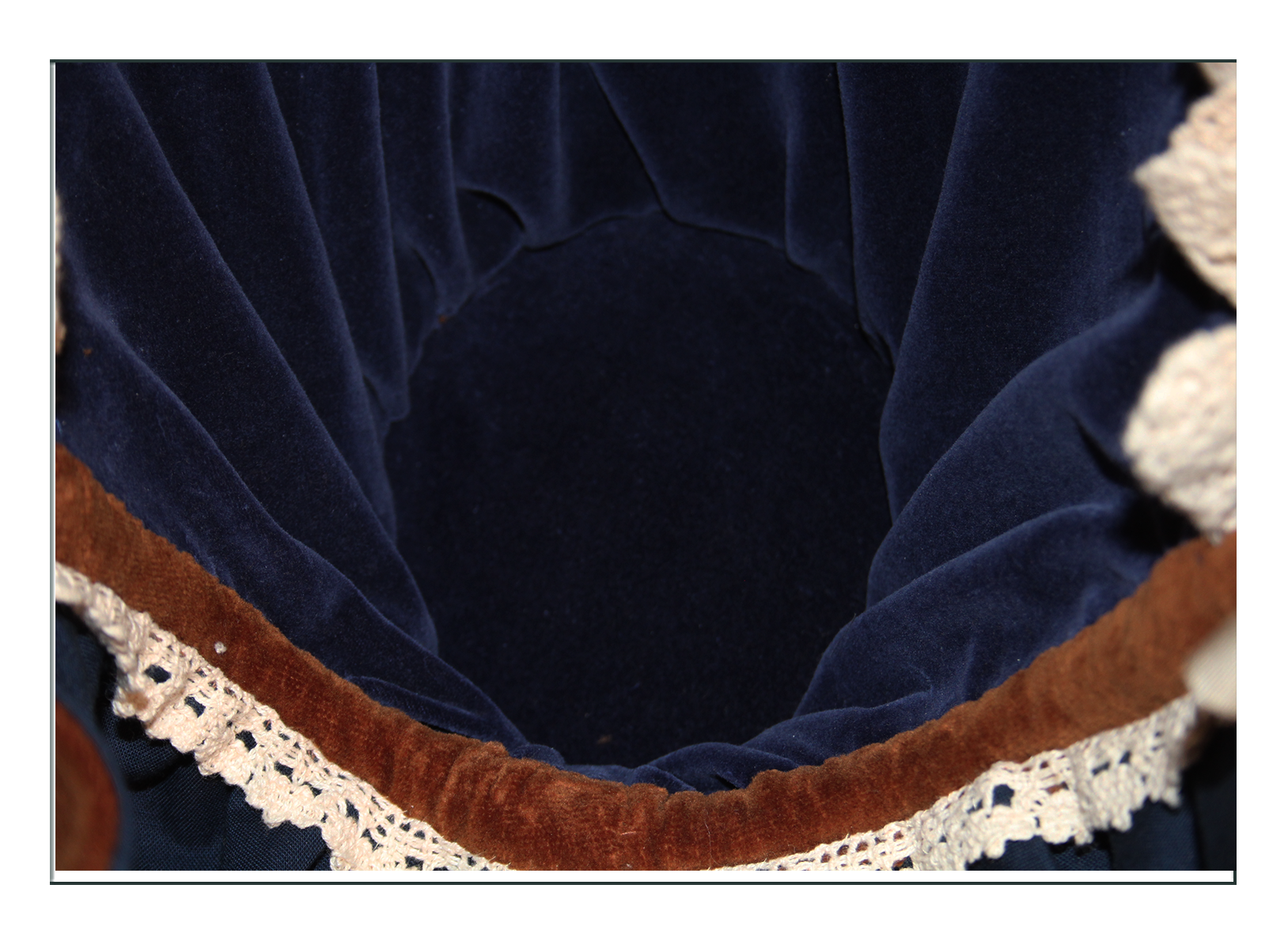

There is an adjustment string inside the back of the crown, and functional string ties, just long enough to tie around the neck, but not long enough to whip around and hit one in the face. Most interesting about this type of bonnet is that you can see its descendants today being worn by religious orders and rural women to cover and protect them.

Flared Bonnet

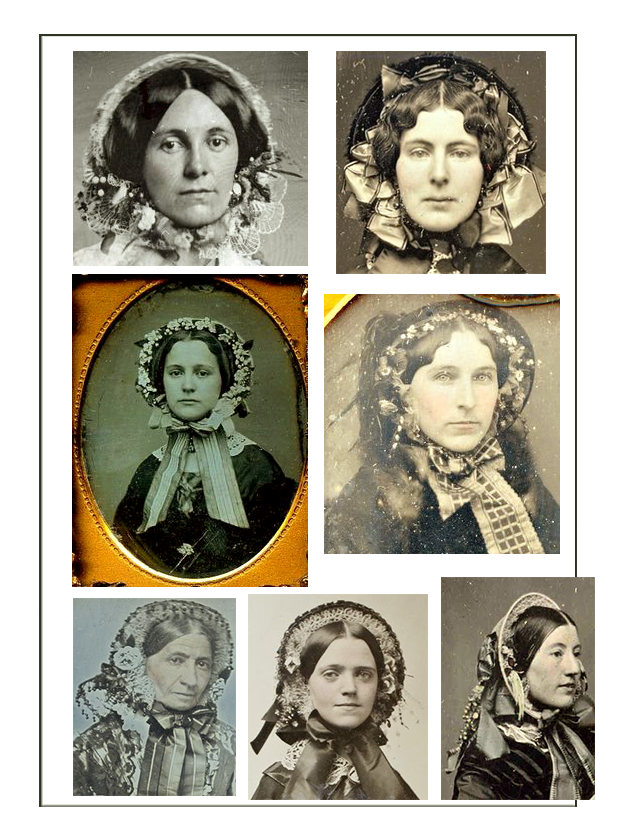

If you compare this with the slatted prairie bonnet, you will see similarities. This is the fashion bonnet equivalent of the functional soft prairie bonnet. It has a large, stiff brim, moderately sized crown, small bavolet, and somewhat wide width.

This particular pattern/design is towards the 1850’s in that the bavolet is short like the Fanchon bonnet that would come in the ’60’s, and that the flare is wide. Most typically, the width, heighth, and depth of a bonnet brim was in response to the hair style of the day. Hair at this time being pulled back and worn low with width around the top of the face, would mean a fashion bonnet had to accommodate a bun in the lower back, and wider hair above and around the eyes. This flared shape does that.

Our bonnet is made of double layers of buckram, and covered by cotton flannel wadding, and an outer layer of velveteen. Complementary colors of velveteen are used to achieve the flat, spare in ornament, and simple look of an 1849 bonnet. It does have a bavolet added; significant as the shape, size, and way it is installed separates it from the later, fanchon bonnets of the Civil War era which were wider yet around the face, but much shallower in the crown with a short (and eventually removed) bavolet in back.

This flared bonnet is a rural and pioneer version of high fashion of the day. This 1850’s specific bonnet design was worn into the 1880’s. There are many examples see in period photos.

In this, the fabric is softly pleated on the brim and crown, which makes it less “severe” than high fashion bonnets of the same shape at the same time. There were many differing shapes worn at the time, but this was a favorite because the brim created a type of “halo” around the woman’s face, which was consistent with the angelic, demure, submissive type of woman that took care of her man that was the ideal of womanhood at the time.

The less angular shape of this vs the fashion bonnets allowed for more room in the crown for more hair. It still looked good if the hair was quickly pulled back, as well as when the hair was piled up or braided as per fashion at the time. That gave it a softer and less severe look, plus it was easier to build, allowing lower class or rural women to have a nice bonnet even if it had to be fashioned herself or by someone with lesser skills than a milliner.

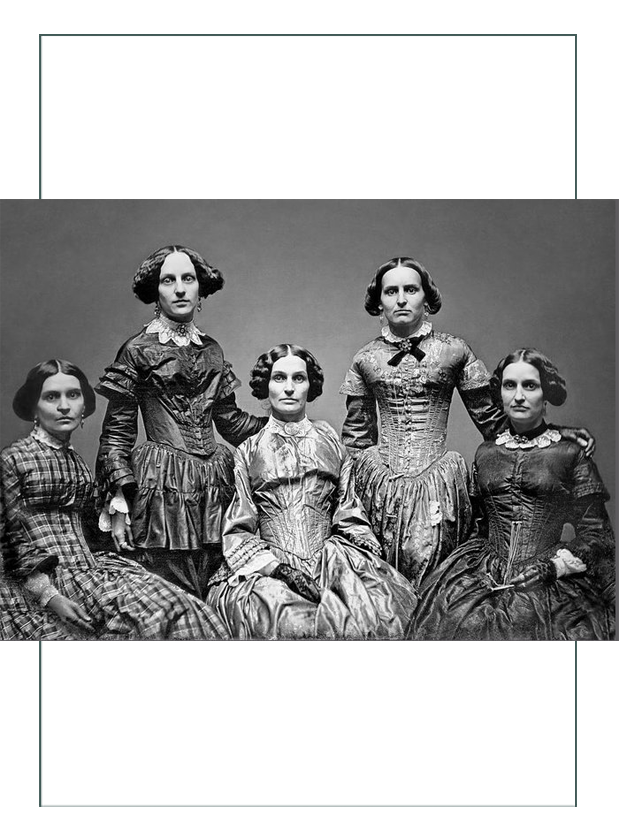

Always stitched by hand, ours is completely. Absolutely everything is reinforced with wire and double hand stitching. As we progressed, we used these extant (real women and real bonnets from the early 1850’s!) examples.

This is made of cotton velveteen, and is fully mulled with cotton flannel. The flowers are ANTIQUES from the 1920’s, and the ribbons are pure Japanese silk. The inside 100% organic cotton lace is kept simpler than these examples because this is a bonnet for a woman in the West and rural area. It is more functional and durable than the high fashion examples seen here, although it certainly looks the same! Note again where the width is specifically designed to accommodate the hairstyle of the day.

The following are being built by Jessica. We may or may not have photos:

Chemise

Drawers

Petticoat

Dress

Accessories

to come!

Click here to go to Jessica’s Historical Context Page (next)

Click here to go to Jessica’s Fashion History Page

Click here to go to Jessica’s Design Development Page

Click here to go to the top of this Page