—— FASHION IN GENERAL 1837-1861——

DRESSMAKING

- Society in Europe & America was prospering

- Population was growing, especially in urban areas

- The idea of standardized clothes was still distasteful to many women, so dressmakers were still in vogue

- The sewing machine, now improved for mass production use, did not help with women’s clothing as much as with men’s, because women disliked uniformity

- Dressmakers even with sewing machines were hard pressed to keep up with demand for clothing

- It was more profitable for a dressmaker to hire out work to the elderly or young rather than use a factory

- Dressmakers had physical shops where they constructed, fit, & sold garments

- Clothes for upper classes were almost all still made by the visiting dressmaker, or customized by the large department stores

- In 1847, an American man with his mother started the successful Royal Worcester Corset Company which stayed in business until 1955

- Royal Worcester American corsets were the most popular & commonly purchased at this time

- Most corset manufacturers were creating a standardized corset & then fitting women into them

- RW designs reversed that thought process in that they were based on a natural line, & then adapted to the function or purpose; e.g. sports, evening gowns, breastfeeding, etc.

- Royal Worcester developed use of the couteil fabric that was functional & quality for a reasonable price, & would be used in corsets forward

READY-MADE

- There were huge shopping malls with department stores in Paris operating at their peak in the 1840’s & 1850’s including Galeries du Commerce et Industrie, Palace Bonne-Nouveau, & Grandes Halles

- Unlike today’s malls, these included inside custom dressmaking shops as well as ready-made items of all sorts from clothing to perfumes to household goods

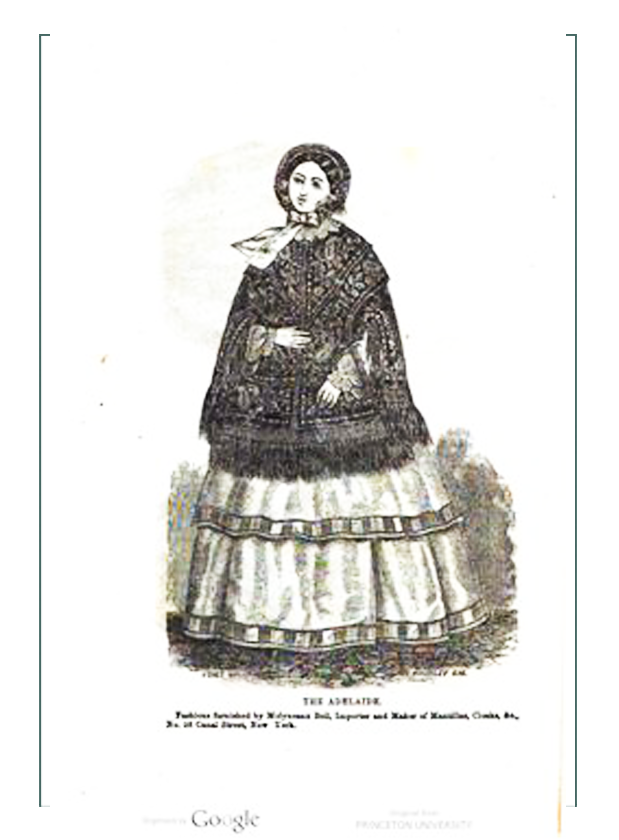

- Ready-made applied mostly to cloaks, shawls, etc that a dressmaker would build during the “off season” in her large shop with apprentices

- Ready-made meant garments were pre-made in general pattern sizes, & then fit to the customer in the dressmaker or department store

- There was no such thing as “multiple” or “off the rack” until later in the decade

- Most ordinary women’s clothing was provided in stores. With buses, & railways booming by 1853, shoppers could easily come to the shopping district

- Drugstores were opened in every department store, selling cosmetics

- By the 1840’s every drugstore had a cosmetician who sold cosmetics with the goal of enhancing “naturalness” & fixing men’s black eyes

PRODUCTION, PATTERNS, & MARKETING

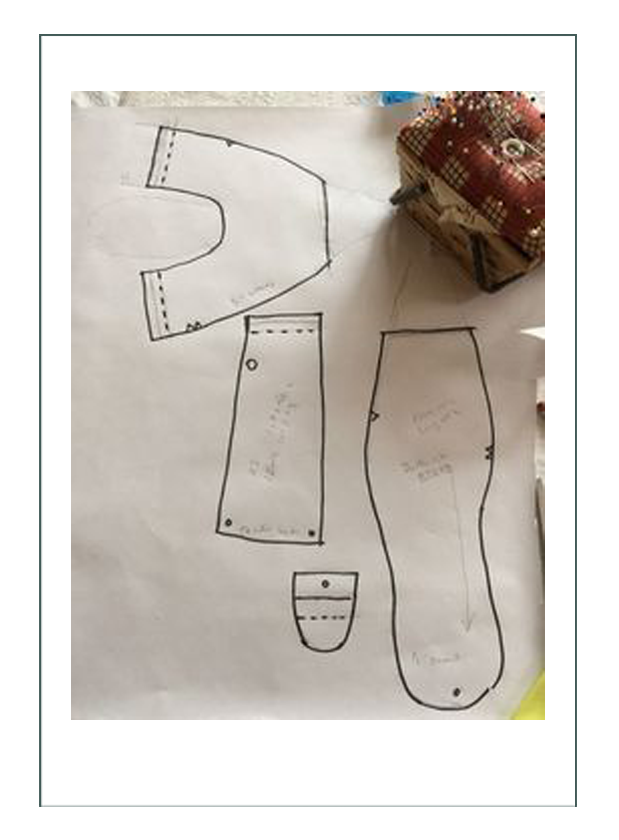

- Paper patterns made the home garment-making industry feasible, but the sewing machine was not yet refined for home use

- Paper patterns were used by dressmakers who switched from the draped design of previous eras to flat pattern design

- Designers through upcoming eras would go back & forth from draped to flat pattern design

- Because mass production meant cutting & then assembling 100’s of sleeves, or collars, or bodices instead of building the whole garment, flat pattern design was more efficient & less costly for factory production

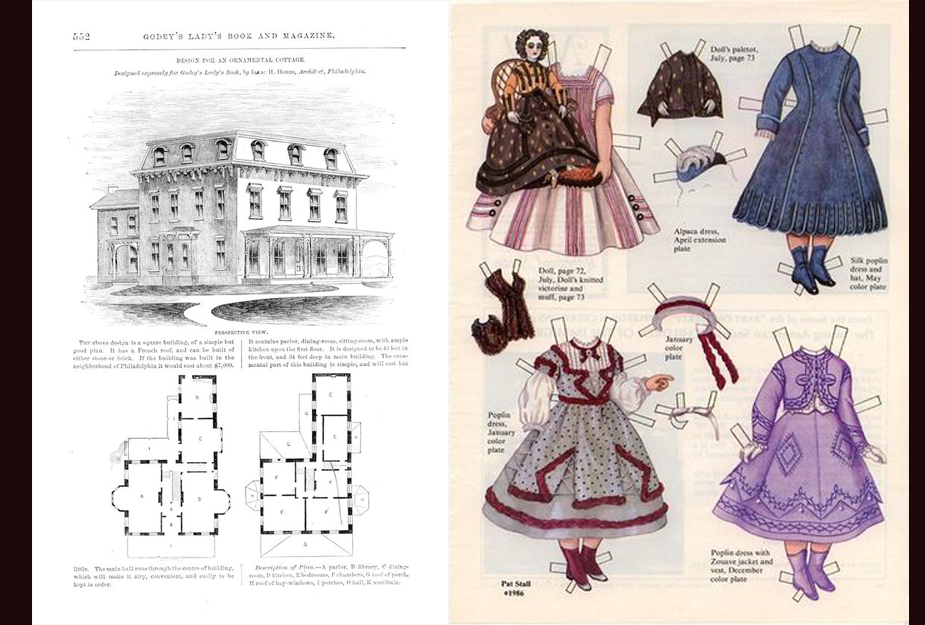

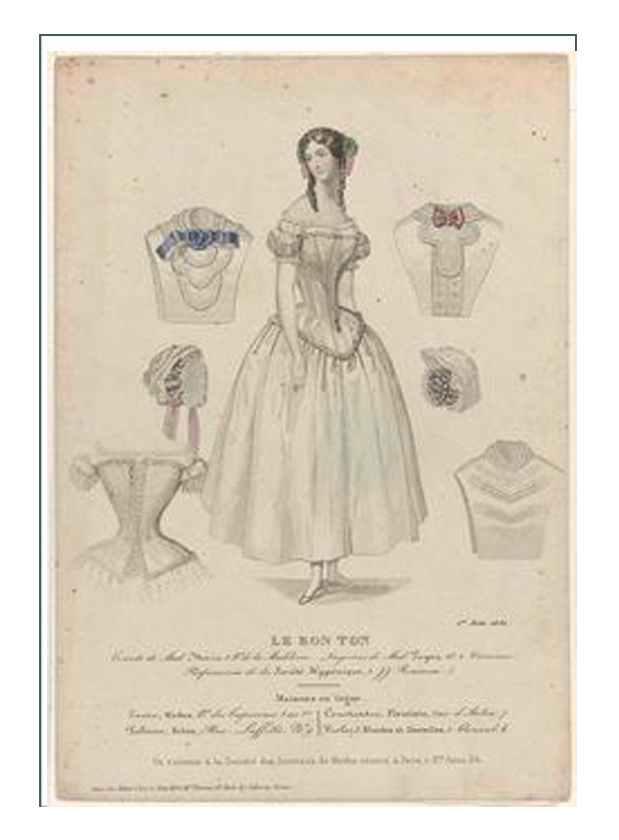

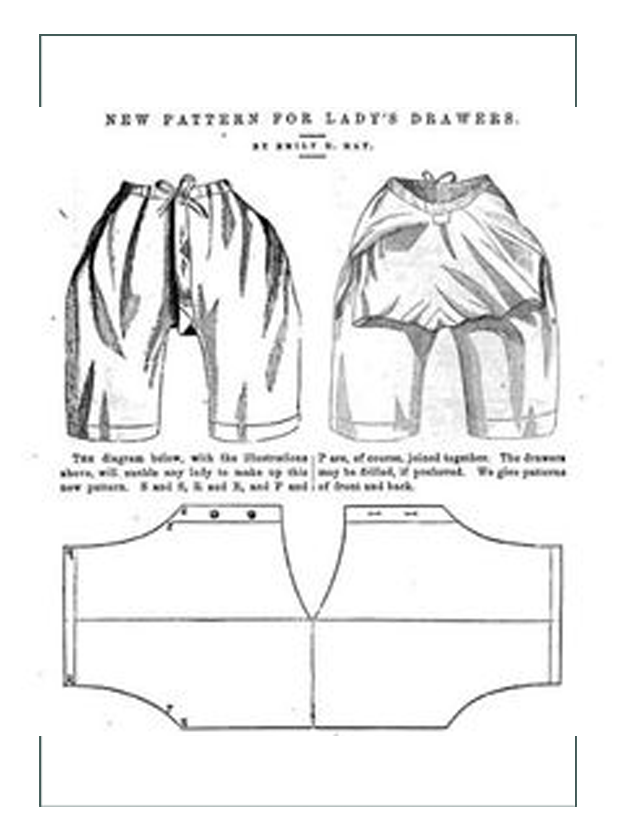

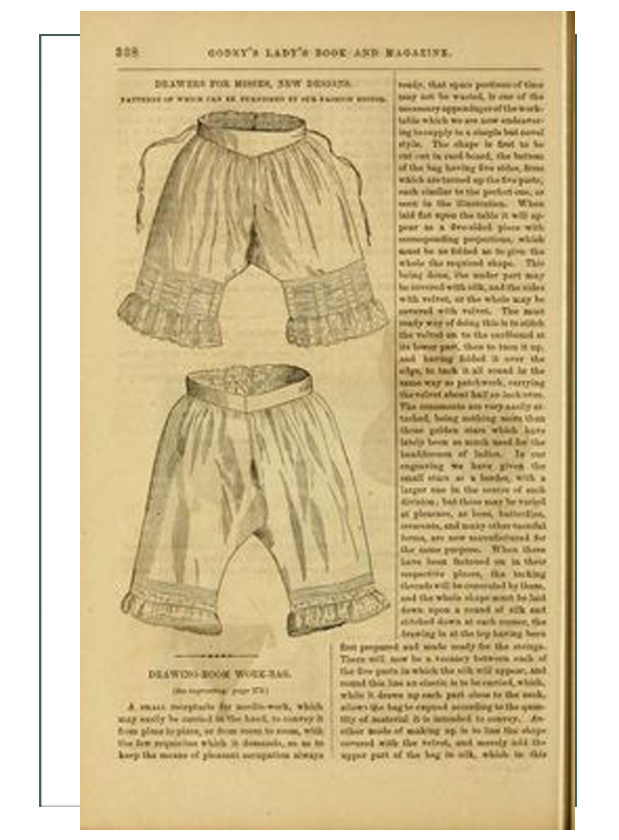

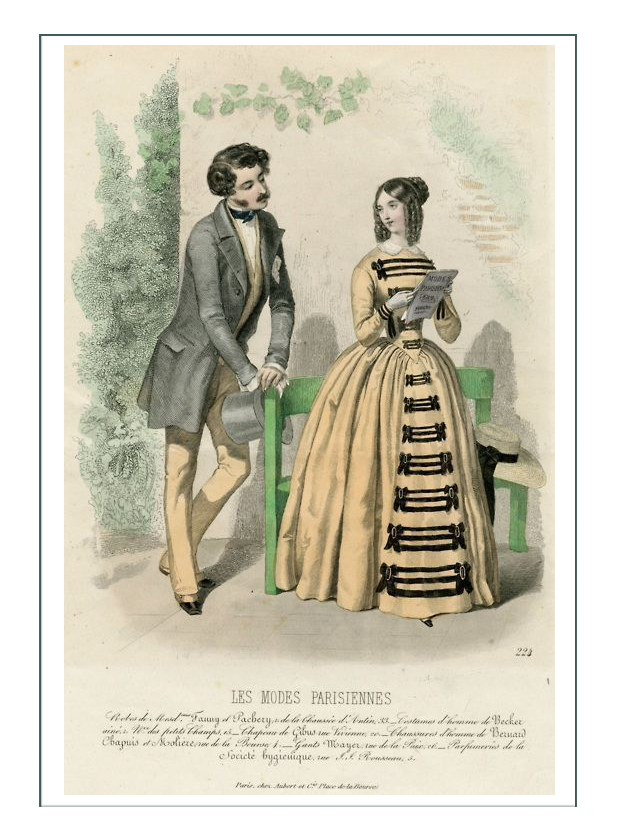

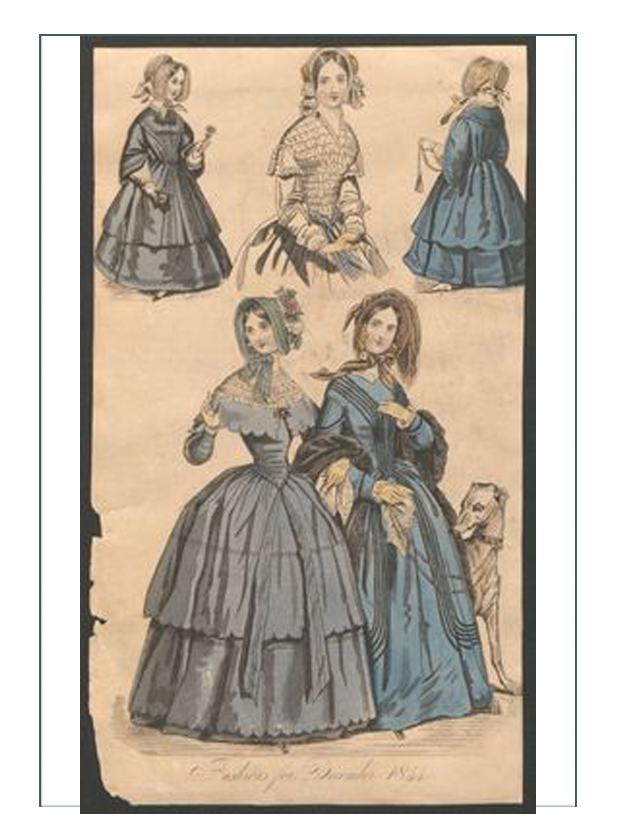

- Lady’s fashion magazines like “Godey’s Lady’s Book” described the current fashion trends for all who could afford to buy the book with its hand-colored illustrations

- “Godey’s Lady’s Book” usually included patterns in standardized sizes based on the “proportionate principals”

- Wealthy women would give the patterns to their dressmaker to make

- Non-wealthy women would not be sewing their own “Godey’s” fashions anyway, but rather a lesser version of it, so lower classes obtained patterns through catalogs or department stores

- Fashion magazines were used almost exclusively by the wealthy & elite

- Photography became common in use by 1840 which allowed women to see what a fashion actually looked like

- Instead of word of mouth, use of old clothing, patterns, samples, or periodicals of past eras used to communicate design, women now most often chose their fashion from photographs

—— FASHION TRENDS ——

AMERICANS EMERGE

- Americans, other than a few railroad, shipping, & banking moguls, really did not have an elite class

- America was still made up of a huge middle class, with the standard of living highest in the world

- While heroes like Lincoln, Clay, & Webster set standards for men, women wanting to be stylish still followed European fashion as they had no American fashion leaders

- Not all American women adhered to European custom

- As with all eras in American fashion history, there were exceptions as women pioneered functional & locally made clothing

- This time period in particular, as the American West was first settled, established its own dress codes for women (discussed as a separate era)

- American fashion, specifically East Coast & Midwest as far as St. Louis, followed the edicts & was restricted by the same rules as Victoria’s Britain was

- The “Boston Lady” was a fashion ideal unique to America. She was a fictitious super-refined American woman that “did the continent” like a Londoner, dressed, spoke, & behaved like European aristocracy, & emulated the ways of the rich

THE RISE OF HAUTE COUTURE

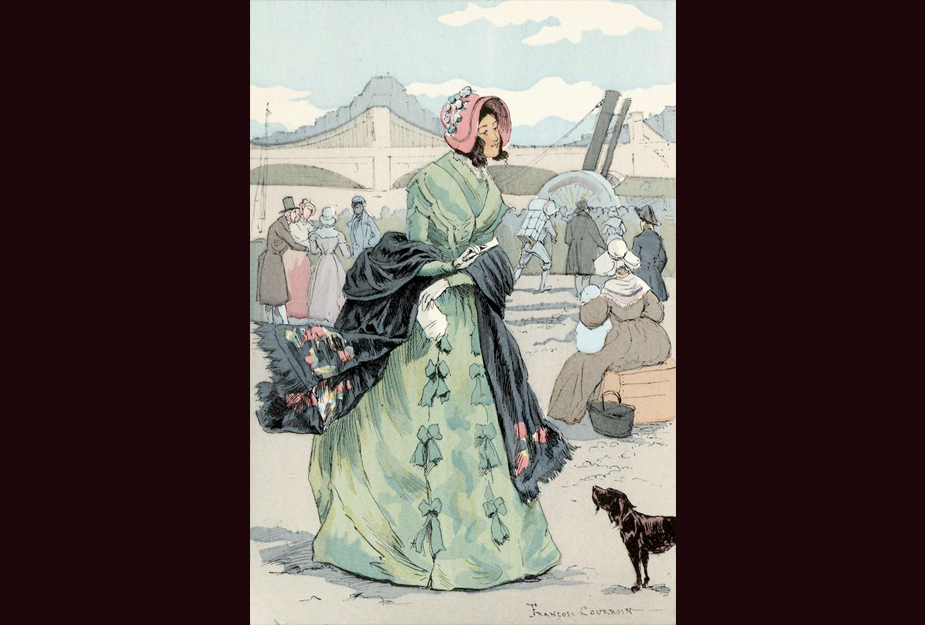

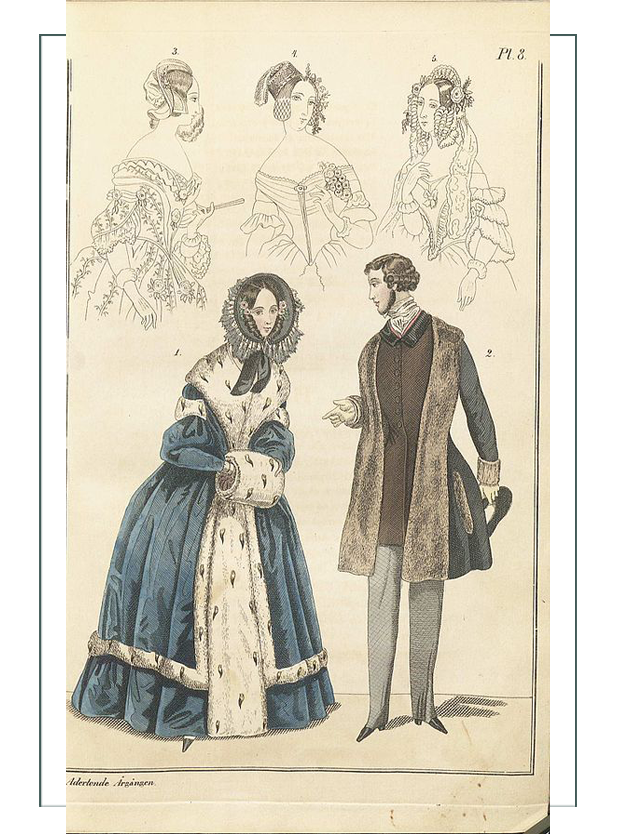

- Early Victorian fashion is jokingly referred to as the time of “drooping ringlets & dragging skirts”

- The era might appear to be the same as the big & embellished previous Rococco, but despite general similarities of line & silhouette, the Early Victorian is actually almost “prudish” in comparison

- Early Victorian differs from the previous Roccoco because of all the strict rules & protocols of fashion dictated by Victoria & the rising designer, Charles Worth

- French “Haute Couture” & the term was invented by Charles Worth

- Worth was an English born designer who told French women what to wear

- What French women wore, was what everybody of European influence, including Americans, wore

- Worth’s concept was that each activity needed its own “costume”, a term he invented

- “Costume” was a complete fashionable ensemble designed & built for a specific function or event to accomplish a specific purpose such as projecting wealth, status, or community standing

- The result of Worth’s fashion was that anyone who could afford it needed to buy huge amounts of clothing

- “Haute Couture” meant there was a lot of dressing & undressing all day; usually requiring a servant or helper & so distinguishing the classes

- There were marked differences between which clothing was to be worn at which time of day

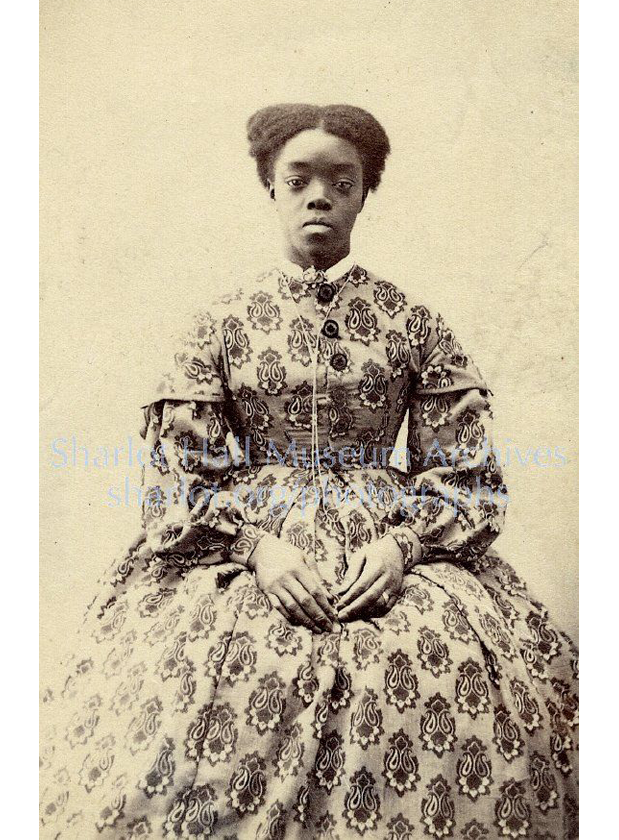

THE PAISLEY CRAZE

- A huge fashion trend that crossed “Haute Couture”, “Tailor Made”, ready-made, & mass produced fashions of the time were paisley shawls & piano shawls of paisley

- Paisley was a specific pattern of color & weave, based on Middle-eastern, Asian, & Eastern designs

- Paisley was used in high fashion for the elite & wealthy

- Paisley shawls also appealed to the mass market of the middle class

- Lower classes would embrace it later after it became in common use at lesser cost

- Paisley originally came from Edinburgh, Scotland in about 1845

- The first paisley shawls were of wool & silk

- Beautiful flimsy silk gauze examples, with bright clear colors were printed for evening wear for the middle & upper classes

- Heavier shawls of wool & silk with light colored centers were used for summer wear, & dark centers for winter

- Printers copied the designs of the woven examples, using wooden blocks & later blocks with the pattern lines inlaid with metal

- Shawls from Scotland were the height of fashion through the early 1800’s

- Norwich, Paisley, Glasgow & other towns printed shawls which were immensely popular

- Great Britain was able to reduce production costs through sub–division & specialization of labor of their mass production textile industry that Scotland did not have

- By 1850, Edinburgh Scottish paisley manufacturers could no longer compete with English Paisley & stopped producing shawls

- Norwich & France continued to produce very good quality examples forward to the present

- They were a favorite wedding present for all classes

- Passed through generations, paisleys were worn from infancy to old age

- They went out of fashion in the 1870’s when they became associated with the elderly

AN ATTEMPT AT BLOOMERS

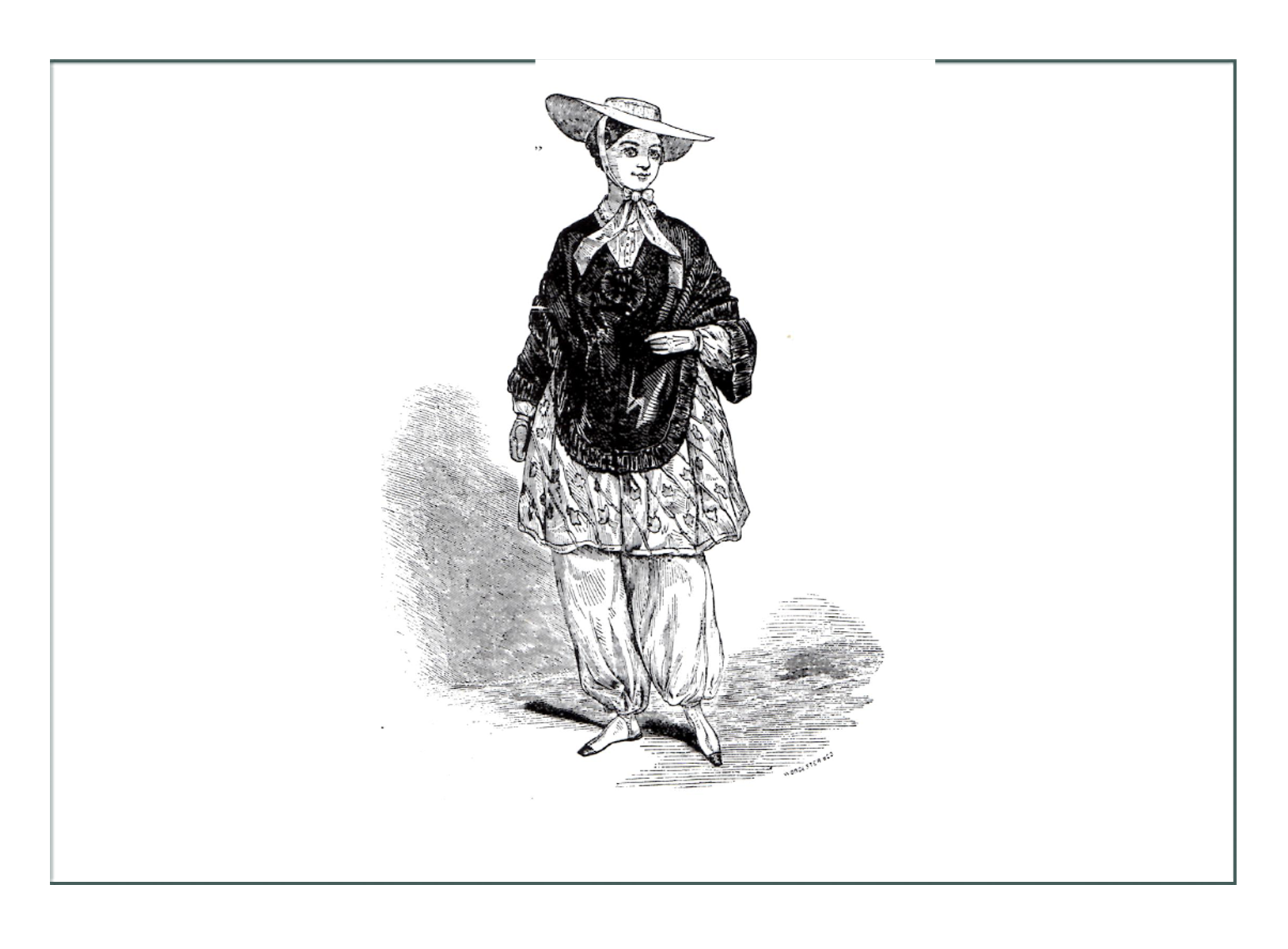

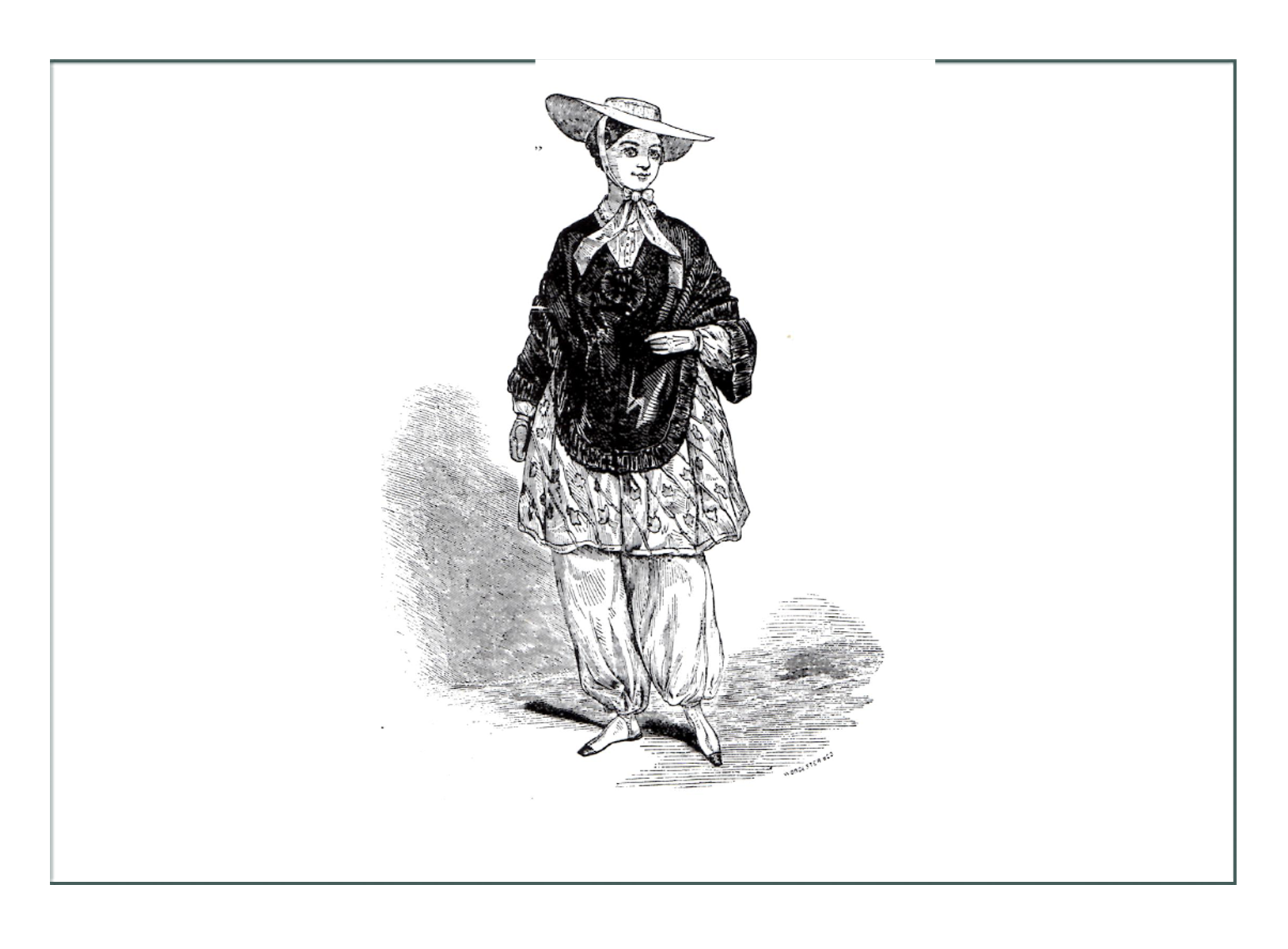

- A third key trend in this era that never took off were Amelia Bloomer’s “bloomers”;

- “Bloomers” were pantaloons worn under a loose fitting blouse-like tunic intended to take women out of corsets while still keeping her modestly covered

- Bloomers were an attempt to simplify the growing complexity of fashion & its understructures, & it failed miserably until 50 years later when the advent of the bicycle demanded women wear something with a split leg

—— SPECIFIC FASHIONS ——

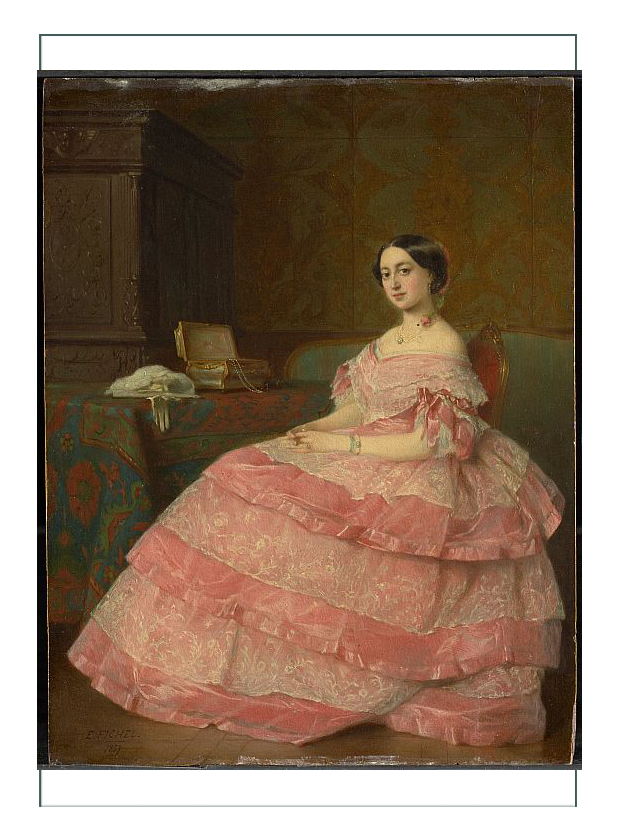

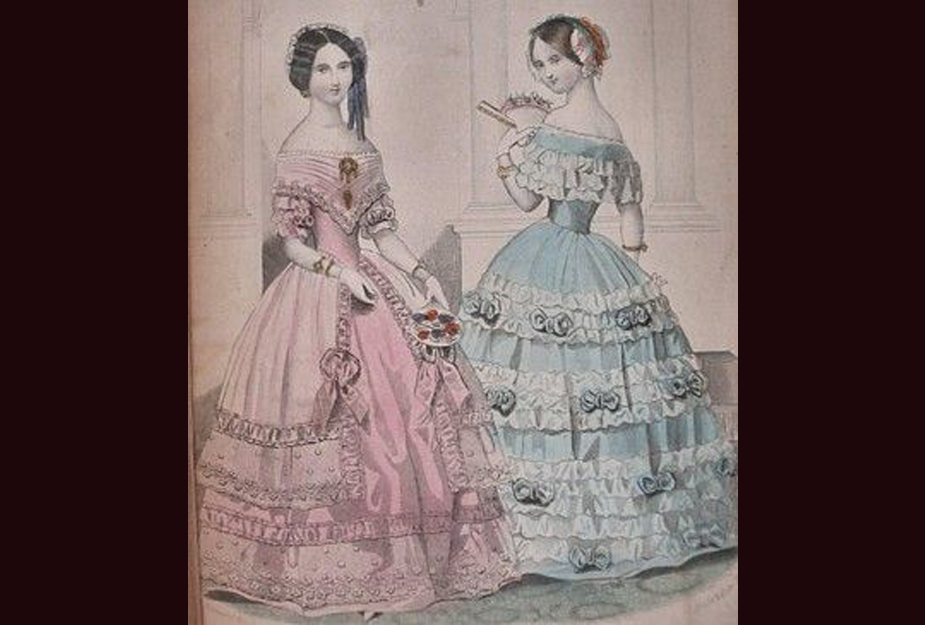

CRINOLINE SILHOUETTE

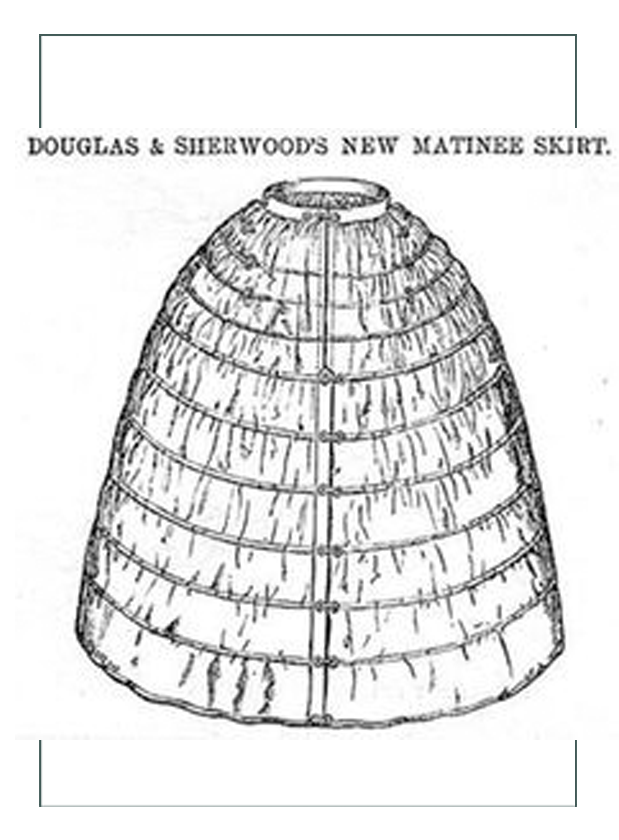

- By the 1850’s the term “crinoline” applied to the silhouette as well as the item

- A crinoline was an undergarment structure which further expanded & stiffened the starched petticoat of the previous era

- It widened the bottom of the profile tremendously, creating a wide shouldered, tiny-waisted, & hugely exaggerated hourglass shape of a bell

- “Belle” (“beautiful” in French) was a term appropriately applied to women of the American south who wore the skirts & structures

- Leading up to 1850, a crinoline was a stiffened or structured petticoat designed to hold out a woman’s skirt

- The first crinolines were made of horsehair (“crin”), cotton, or linen

- “Crinoline” also meant the hoop skirts that replaced the crinolines in the 1850’s & 1860’s

- NOTE: In form & function, hoop skirts were very much like 16th &17th century farthingales & 18th century panniers in that they were made of stiff structural materials combined with the horsehair & fabric to hold the skirts into specific (large) silhouettes

- Crinolines were worn by women of every social standing & class, from royalty to factory workers

- Their use was subject to media scrutiny & criticism, & there were many caricatures, jokes, & satires about them in magazines like “Punch” at the time

- Crinolines could be hazardous, as they were extremely flammable

- Other crinoline hazards included hoops getting caught in machinery, carriage wheels, gusts of wind, or other obstacles

- Crinolines & the later hoops allowed skirts to spread wider than ever, up to 6 yards (18′) in diameter at their peak in size & depth in 1857

- The steel-hooped cage crinoline was patented in 1856

- Steel-hooped cages were distributed by agents, intensely marketed, & mass produced in huge quantities by factories in Europe & the US

- Whalebone, cane, gutta-percha, & inflatable caoutchouc (natural rubber) were used for hoops, although steel was the most popular

- By 1860, the hoops began to reduce in size a bit

- The smaller crinolette & the bustle had largely replaced the crinoline by the early 1870’s

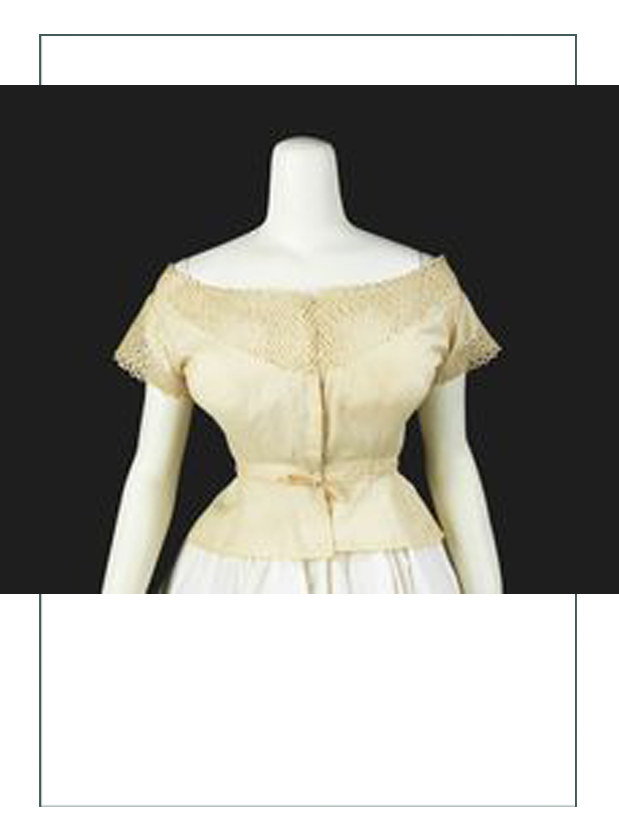

BODICES

- The separate blouse & skirt was introduced in this timeframe

- Lines shifted from the vertical to the horizontal on top as well as on the bottom of the silhouette, assisted by shorter, wider bodices

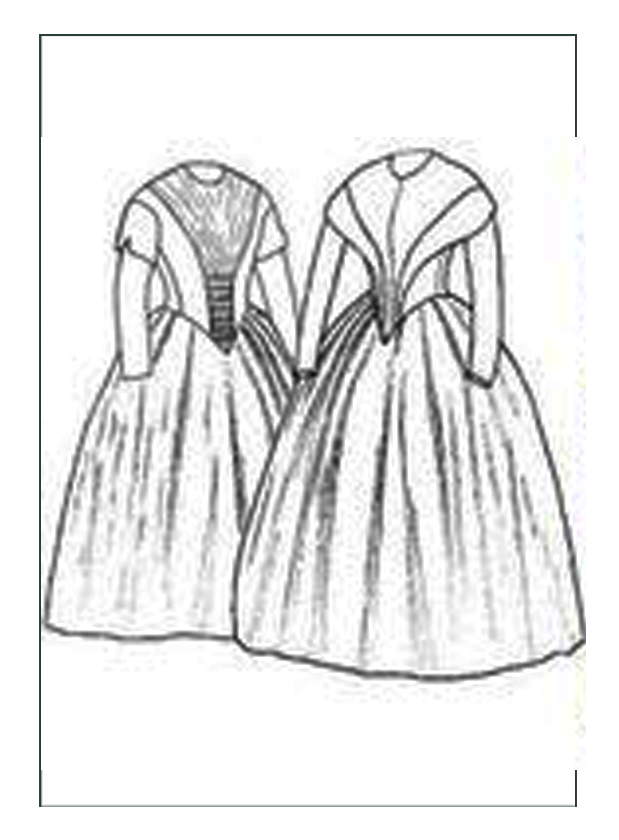

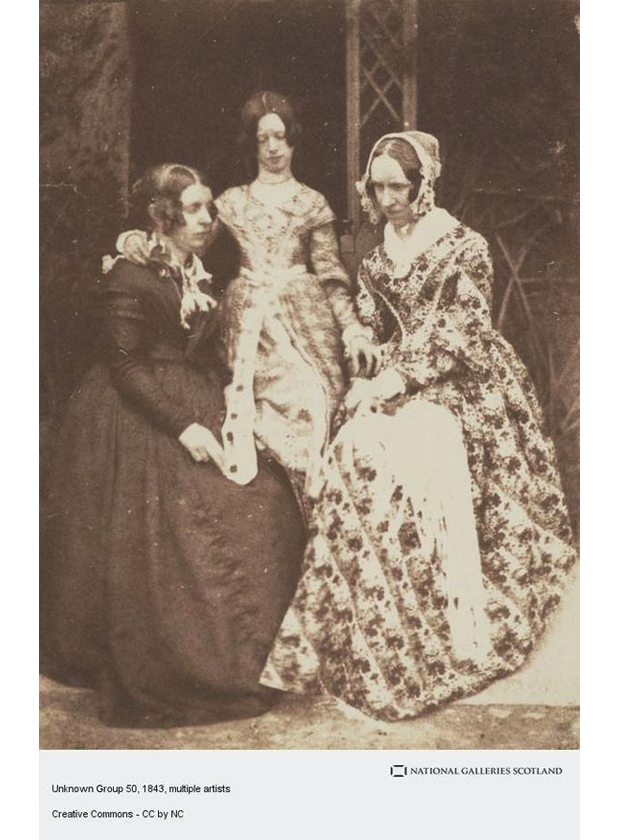

- Women’s 1840’s day dresses had boned bodices with dropped shoulders

- Dresses had a fan-front (gathered) bodice that formed a point below the waist

- Dresses had piping at the waistline, armscye, neckline & shoulder seams.

- Dresses had much less ornamentation than the previous era

- Bodices were worn off the shoulder

- They featured a rigidly boned elongated shape with a waist that formed a perfect point in the front

- Shoulders were extended below their natural line

- Generally necklines were worn high during the day & wide in the evening

SLEEVES

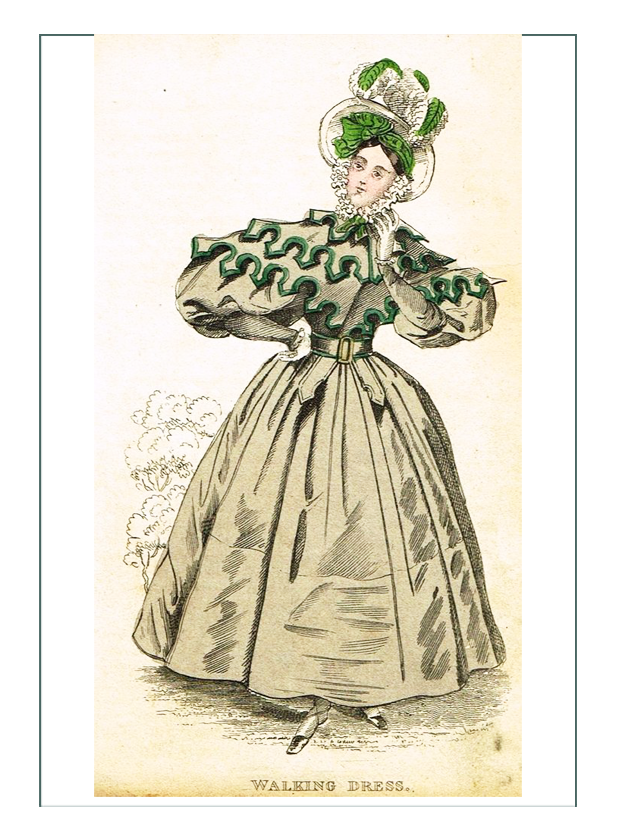

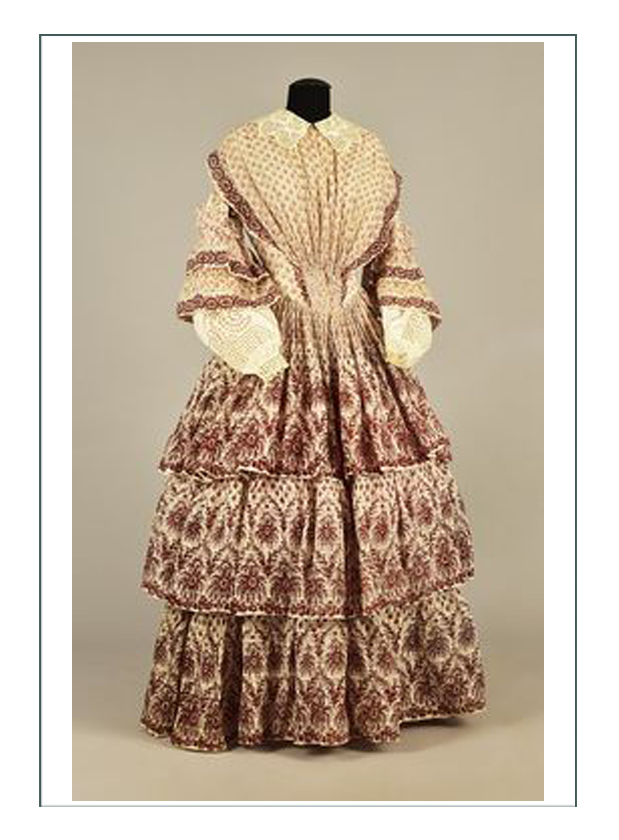

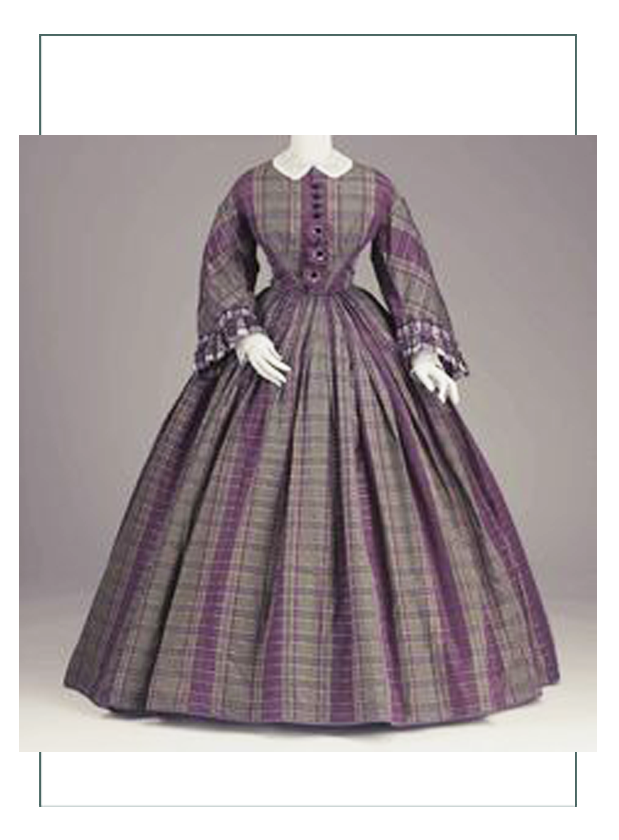

- A new triangular, cone-shaped silhouette emerged featuring new pagoda sleeves

- Huge sleeves had suddenly collapsed in 1836

- The new form-fitting sleeves were sometimes so tight that tiny pleats were inserted at the elbow to aid in movement

- Sleeves in the 1840’s were short & tight with either puff decorations of lace trimming

SKIRTS

- In about 1852, skirts become even fuller than the previous era when they had widened to a “bell shape”

- It was still a “bell shape”, but a much larger “bell” formed by cartridge pleating

- Horizontal flounces or tucks were added to the base skirt to give it width & volume

- Trimmings of tucks & pleats were used to emphasized the new line

- Skirt hems lowered to the floor

- Starting from the mid 1850’s until the end of the century, women’s skirts & understructures continued to get more drapery, a more layers, more stiffening, & more complexity

- As the era progressed towards 1857, the skirt became very domed in silhouette, requiring yet more petticoats to achieve the desired shape

- The trend to get more & more ornate continued into the 1860’s

FABRICS & TRIMS (see section on Dyes & Colors)

- There were many more fringes, beads, bugles, & bows with ruchings, loops, & swirls added as time progressed

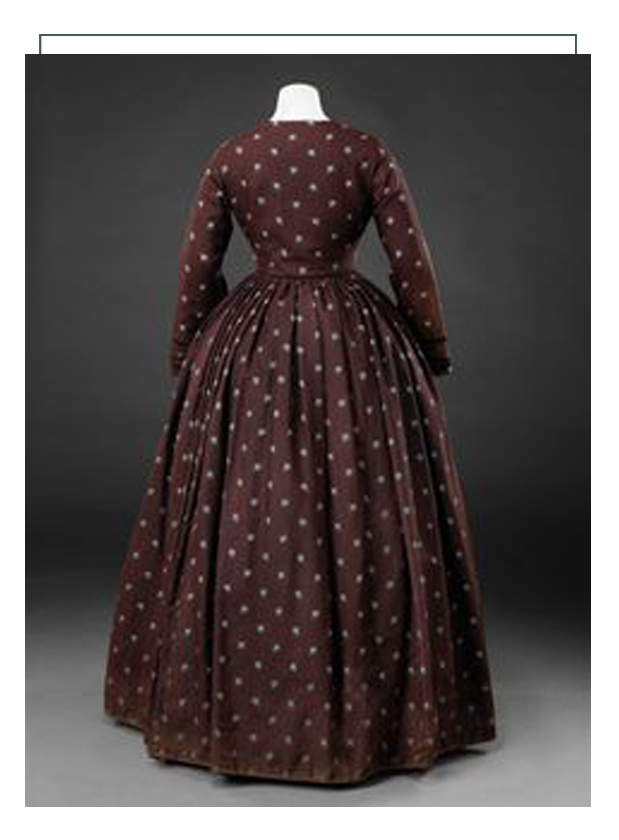

- Solid, colored fabrics were more in tune with the new solemnity of the era

- Colors shifted to darker tones

- Prints & patterns gradually were introduced & became the norm

- The huge expanses of fabric were crying out for visual interest which large plaids & border prints provided

- Fabrics were the same stiff textured cloth as previous eras in winter or cool climates

- Light cottons were typical in summer

- Bright printed & woven fabrics were popular

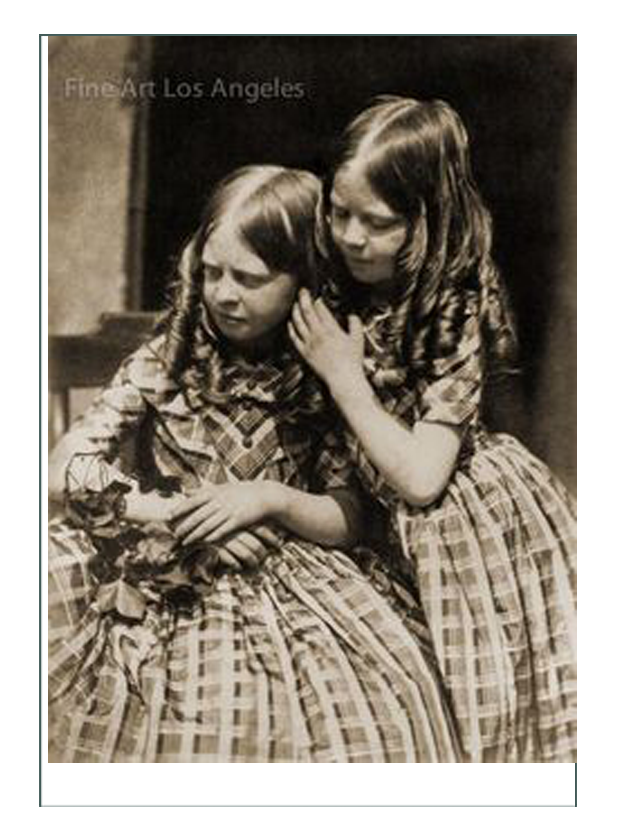

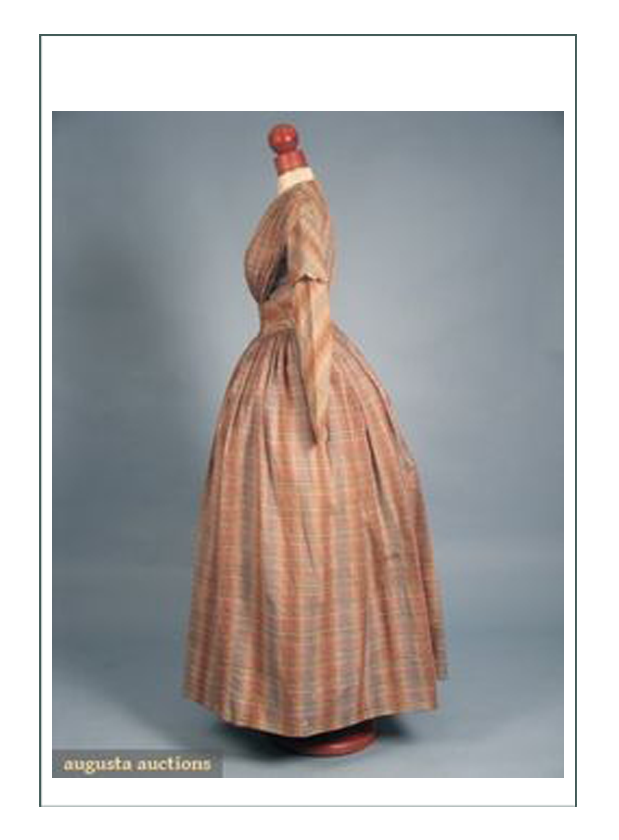

- Daytime colors were brown, rust, gray, & green & included Scottish plaids, following the lead of Victoria who loved them & wore bright authentic plaids in silk to social functions

- Pale pastels were for evening

- The designs of the main dress were repeated in matching pelerines

UNDERGARMENTS

PETTICOATS

- Multiple layered petticoats & crinolines provided the fullness of the desired silhouette over the very tightly laced corset

- Numerous petticoats were worn

- The more the crionoline was worn, the less petticoats were worn

- Some stiffening was used to support the skirts, but with the advent of the crinoline, only 1-2 petticoats became necessary

- 2 petticoats were preferred for modestly, as the crinoline did not count as it might sway or blow up revealing the naked woman beneath, or at least an ankle or foot

- Petticoats were decorated with “broderie anglaise” which was tucking & lace

(more petticoats discussed below)

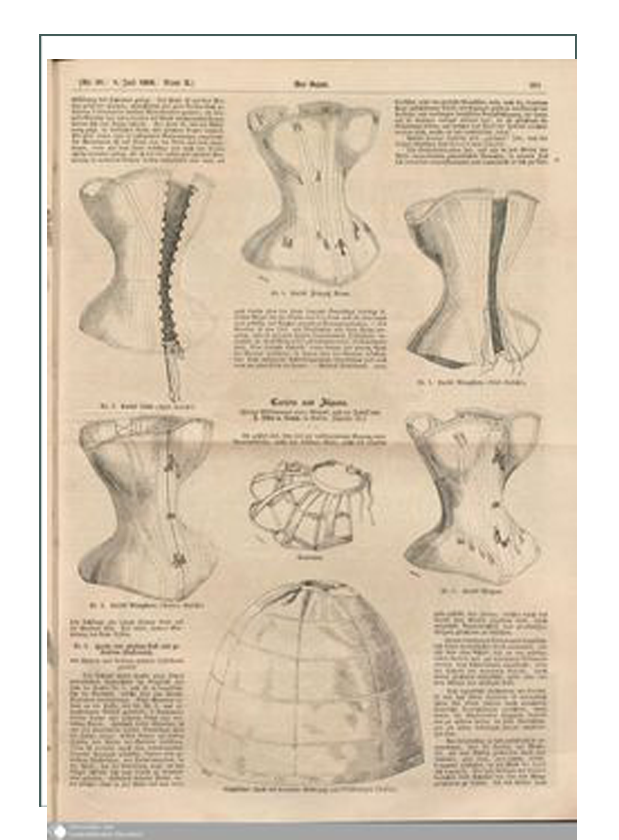

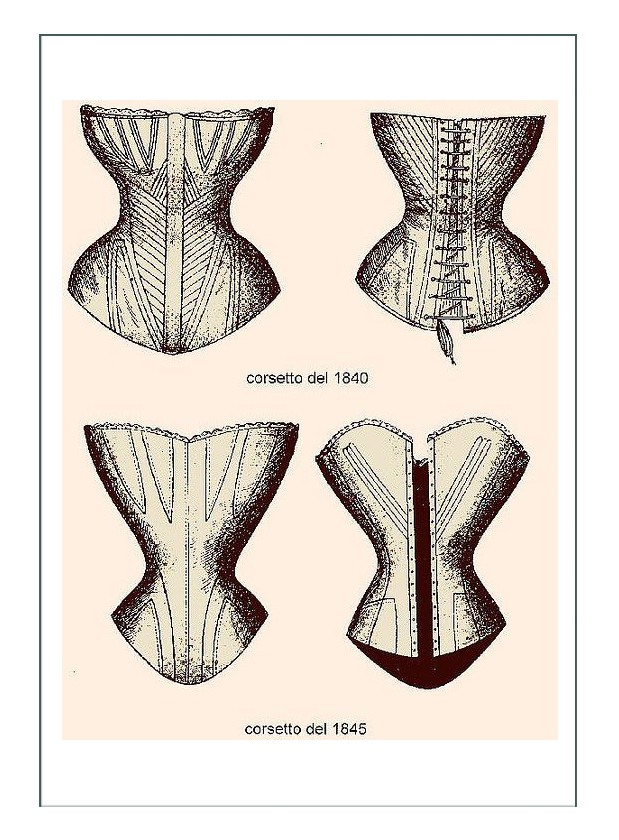

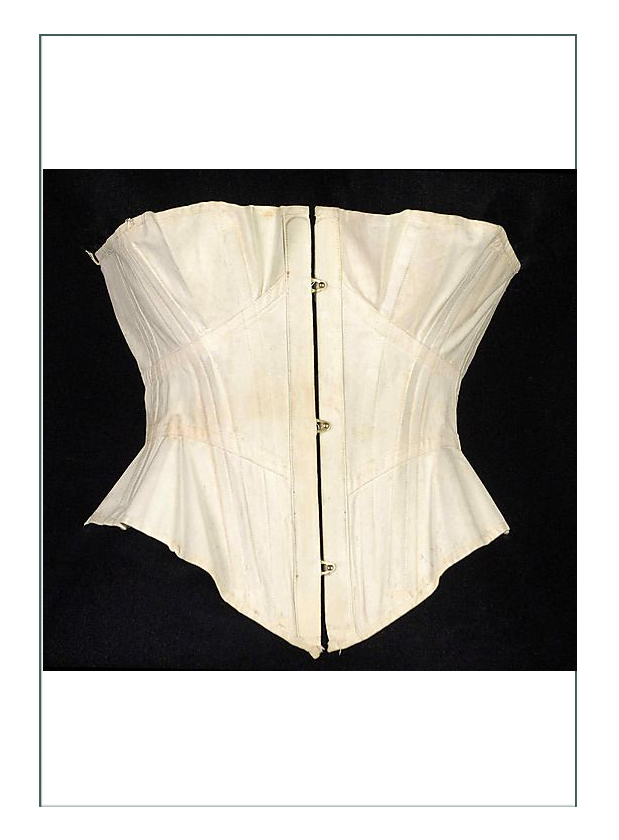

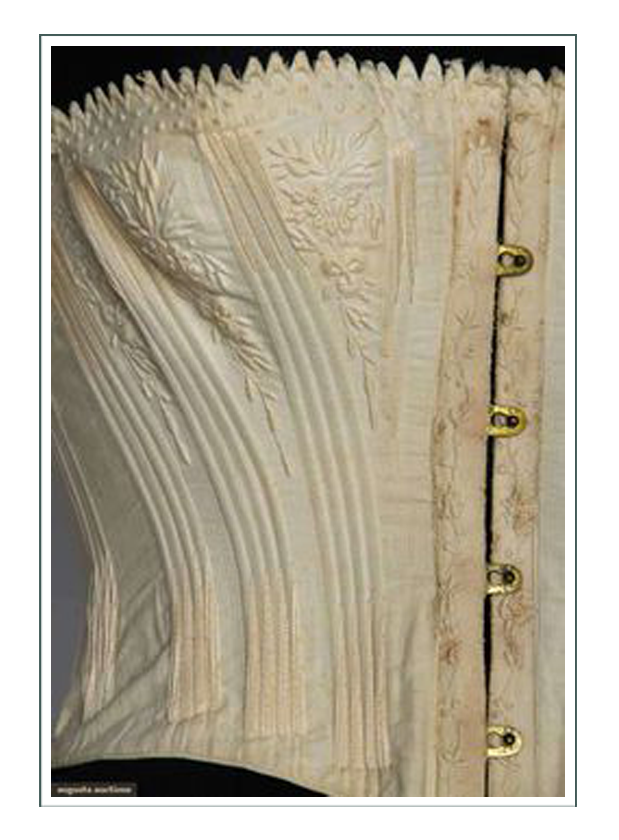

CORSETS

- The corset returned in full force with intent to mold the body into a proscribed shape, rather than to trick the eye

- Waists became smaller & even more tightly laced than in previous eras

- Strong metal grommets made the tight lacing possible

- Previous eras had hand sewn eyelets, which would not have taken the stress

- Center backs & fronts of the corset had additional metal “lacing bones” to take the stress of lacing off the fabric

- New innovations in innovative “busk” closures for front & back made the entire garment much stronger & durable

- Design was flexible with many construction methods available

- By the 1850’s, there were 4 basic corset shapes, with variations by intended activity

- There were corsets for sports, riding, maternity, evening, & travel based on the 4 main concepts

- The 4 corsets all had in common a design which produced a wide & very round bosom with a tiny waist

- No emphasis was made on the hips except to make the corset long enough so that it sat comfortably on the waistline

- Gussets that had been present since the 1790’s in corsets disappeared, to be replaced by seaming

- It was the new shaping of seams that would have a major effect on corsets until the end of the century

- In general, all corsets of the time had colored outer fabrics & a white lining

- Sateen & jean “couteil” fabric was produced in America specifically for corsetry

- Silks, satins, & batistes for decorative outer layers were made in Italy

- Nettings were used for summer corsets

(more on corsets below)

HEADGEAR

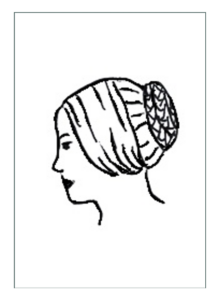

- Hair was neatly pulled back into a snood. Snoods were lace or linen coverings over most of the head or at least the back of the head, such as food service workers wear now

- Snoods were worn in the evening too, but they were ornamented with pearls or other decorations for formal occasions

- Hats were now small & worn tipped forward, as introduced by Eugenie, Empress of France

ACCESSORIES & ODDITIES

- Women wore a little rouge, powder, & eyebrow pencil

- Less proper ladies wore pearl & violet powders & rouge

- Women wore false ears complete with earrings

- Parasols & pouch bags with wooden handles were carried by every woman

- Gloves were worn constantly for each & every situation except meals when they were discreetly placed next to the napkin ring

- Gloves were made of lace or silk net; often worked with gold threads for the upper classes

- Early Victorian jewelry included a ribbon around the forehead with a jewel in the center (“ferronniere”)

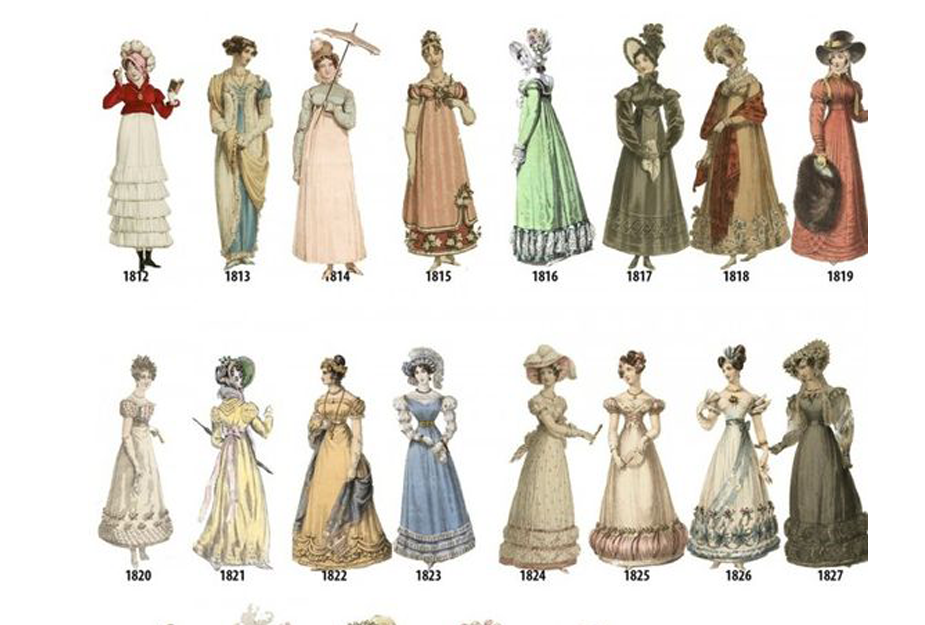

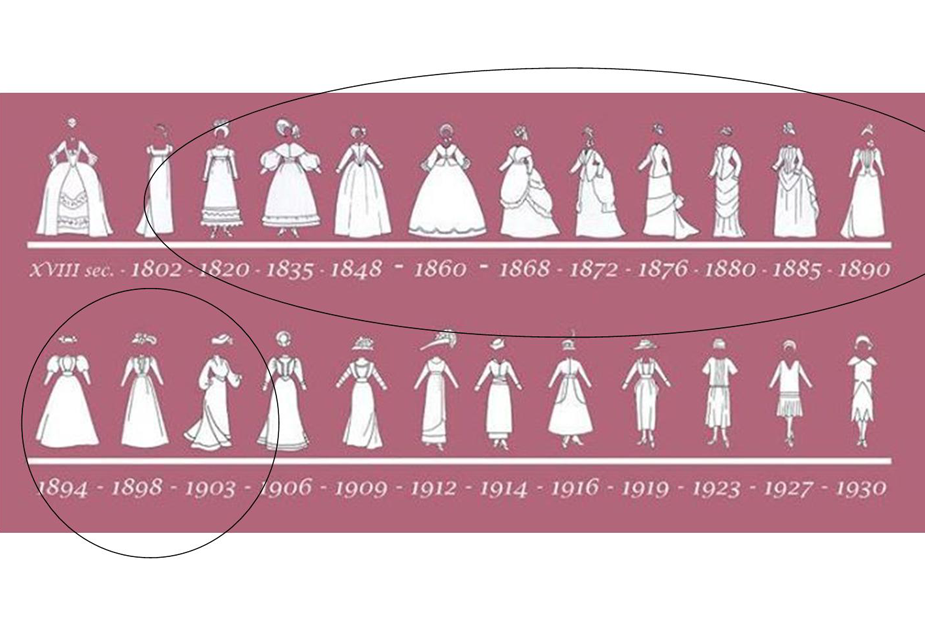

Out of Regency; into Victorian

The year 1846 is part of the early Victorian Era. 1837 was the year Queen Victoria took the throne and began to lead fashion. Prior to that, fashion had been transitioning out of the French focused Regency Fashion era, and into Victorian.

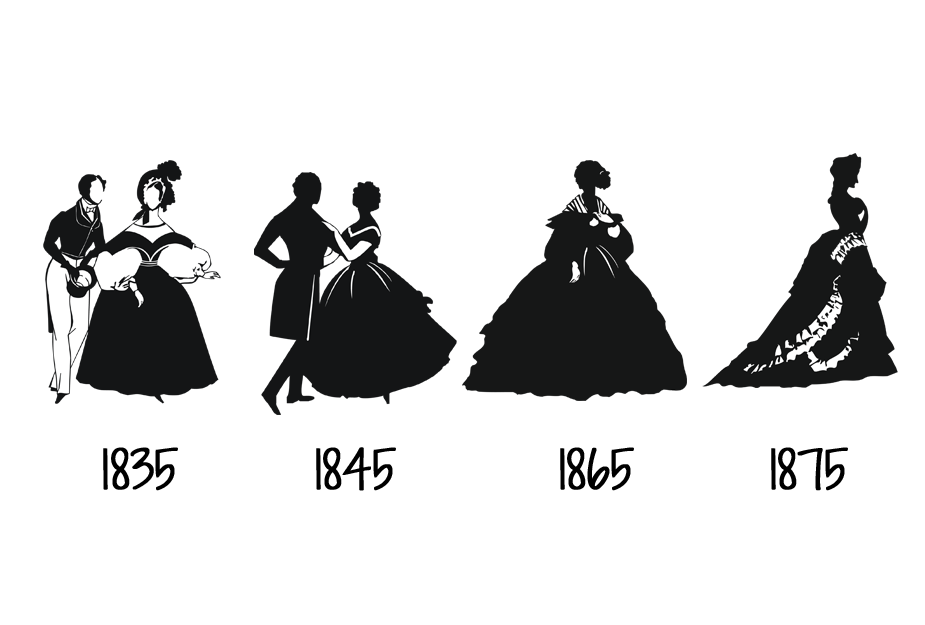

From 1800-1836, the waistline kept dropping, the skirt got wider and stiffer, sleeves and necklines dropped an became structured and ornamented, and bonnets followed the hairstyle of the day. The important evolution was that of the corset and the petticoat. The corset went from a soft, corded, and long garment used mainly to smooth out lumps, into a structured and controlling garment (see pages on the history of stays and corsets for details).

The petticoat went from wearing nothing at all underneath, to become bigger and wider and stiffer, with more and more added as the fashion evolved into the various silhouettes which varied by length or width of bodice and shoulders into the “hour glass” focused on a tiny waist, wide shoulders, and big hips covered in a huge skirt by the 1860’s.

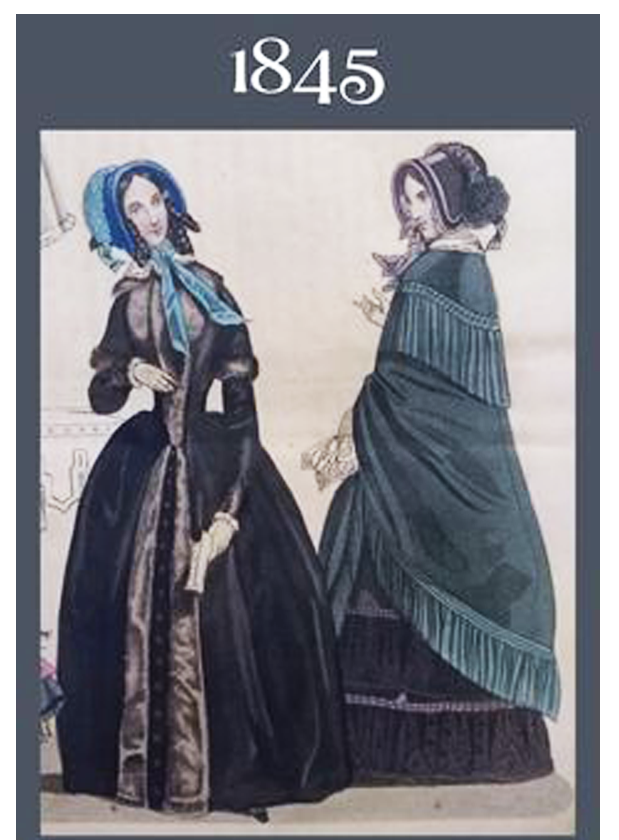

You can see in the timeline above, that in 1846, the silhouette and the fashion ideal was rather a merge, or a transitional time between two rather extreme fashion ideals. It ended up looking a bit “normal” to our modern eye. Features of the 1846 silhouette are long center pointed bodice, moderate and long sleeves with somewhat dropped shoulder, moderately full and symmetrical small “bell” shaped skirt, some focus on a small waist though not extreme, natural breast position, and almost natural hair with small bonnet or head covering.

The key to the 1846 fashion era are the undergarments, notably corset and petticoat. These had probably changed the most as the desired silhouette evolved, and both were in transition of sorts between the Late Regency and Early Victorian styles.

As we see in the above silhouettes, a moderately wide skirt, dropped sleeves, almost natural waist and bust position, and symmetry marks 1845-46. In 1835, the shape was created by one or two corded or stiffened petticoats worn over a shift, a soft corded corset, and no drawers. By 1845 minimalistic drawers were being worn (a nod to Victorian morality and modesty – not to mention warmth at last). Petticoats were still being corded and stiffened, but with the wider skirt, more petticoats were being added until the crinoline was made popular in about 1855.

High Fashion and the Wild West

Fashion is the result of what a woman knows about, has access to, can afford, and likes given her situation.

Before detailing the 1846 undergarments, we need to make a note about culture (refer to the Historical Context page for what was going on in the world, in America, and Pioneers in the West). Historians document through diaries and records that women had to choose carefully what they would take headed west. There are funny stories about trees full of crinoline hopes on the Oregon Trail where it headed into the mountains.

Women pioneers of the 1840’s were the first Euro-American females to traverse, and life on the trail was not as easy as it would have been a decade or two later as they were blazing the trail, literally and figuratively. A woman traveling with her husband in a military or scientific expedition, or coming to serve as a missionary or with intent to settle, would have known about fashion from whereever it was she came from.

Some were making multiple “jumps west”, so might not have ready access to know what was fashionable. Others might have catalogs or books like Godey’s although it is not likely she would have carried those with her due to weight and having little function. At the end of the trail, and with railroads coming ever closer, however, she might have had access to catalogs and fashion ideas.

It is most likely she would hear about fashion through others: letters, notes, communication with those who followed her west. It is very likely unless on a financed expedition such as by a church or organization, she would have little money. It is even more likely she would not have access to materials, notions, fabrics unless it was carried by someone on the trail.

This is one of the reasons we would suggest the depiction to be a trader on the trail. It would give Jessica’s character more access to materials, and a bit higher fashion knowledge than others who might be high in the mountains or far from supply chains that lay at the time along waterways and trails. Her proximity to the junction of the trail and being a trader would give her time, money, and access to information and goods.

An important note though on women of the West which has been documented by historians: while most pioneers and settlers knew about what the current fashion in the east was, and wanted it, they were in actuality 5 or 6 years behind the current trends. Women such as the mother, Caroline, in the Laura Ingalls Wilder fictionalized stories of their continued leaps in pioneering, often referred to her efforts to maintain the latest fashion, even if it meant sacrificing something or making her own bustle. One can assume from various diaries and periodicals too, particularly of the homesteaders who came later in the 1880’s-1910’s, that they came from fashionable homes, and tried to retain some semblance of that.

It would be assumed then, that we are actually building an 1840 ensemble, with as much “current fashion’ (1846ish) that the character could know about, want, or be able to implement.

How that comes out in production, actually comes down to the undergarments. We must assume Jessica’s character was wearing some from 1840 like her good old corset for work, while retaining and building herself some of the latest fashion, though a “low fashion version” of it, for outer dress and accessories. In other words, it’s most likely her undergarments might be out of date, and her accessories the latest fashion, with dresses varying depending on if it was for work, riding a horse, or going to town.

We find that typical of all historically accurate depictions. Like today, a woman usually has at least one outfit to wear for “dress up”, one to work physically in or exercise, and at least one for the rest of the time while at home.

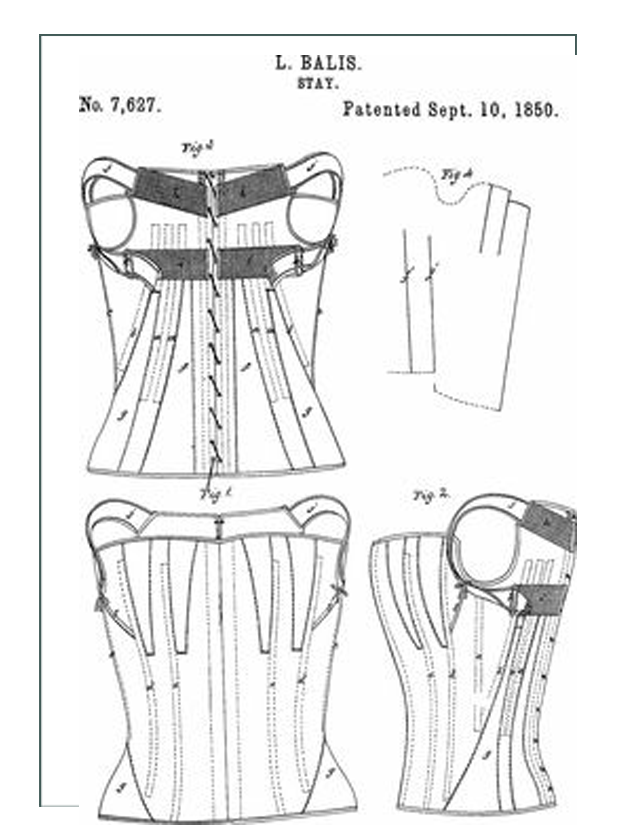

Corsets

There were many “correct” types of corsets for the period 1840-46 because it was a transitional period between the soft, long, corded smoothing corsets of the late Regency, and the metal boned, stiff, shaping and waist cinching corset of the 1850’s forward.

The Regency era focused on “round pert apples on a tray”, or a lifted and separated and rounded breast. They didn’t care much about what happened with the waist or hips, since the waistline was above the natural position and the skirt was full and one never saw the hips:

By 1839, the shape was still similar, but the bust gores had split into 4, metal boning had been added, and several styles started to lace in the front, although just back lacing was more common:

A few more corsets appropriate for this depiction include a modern reproduction (woman) 1840’s “demi-bust” corset, and various details of late 1840’s, early 1850’s corsets. We might consider front lacing which was typical of the time:

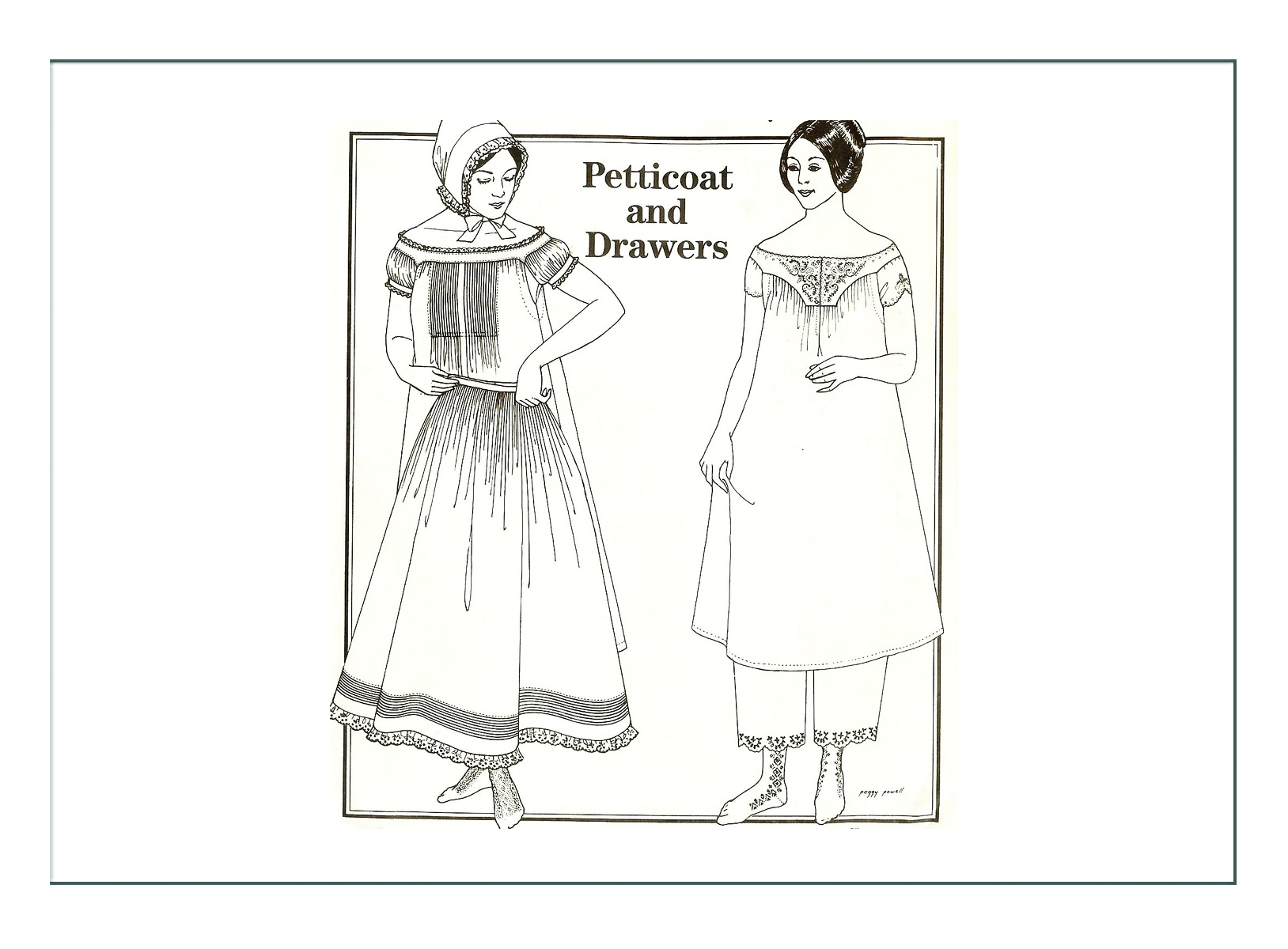

Petticoats

While the corsets were the key garment for the shape of the mid 1840’s, the petticoat is perhaps the most interesting in its evolution from Regency to early Victorian eras.

What started as nothing underneath in 1805, ended up being a voluminous over skirt with flounces worn over a crinoline hoop in the 1860’s. In between those dates, was a continuous enlargement and aggrandizement. It is logical that for an 1846 depiction then, the petticoat would be something “in between.

This is somewhat true, but as with all fashion eras, there is never a clear line that is cross between one thing and the next. Some women quickly discarded the old and grabbed the latest and newest, while others clung to the old and never bought new.

In this, the rural and Western depiction must be taken as priority in selection. Also in consideration, as with the corset, is the ability to stretch the depiction somewhat to get the most for her money. Since there were women with any of the style below in the 1850’s, we will consider for design develop (next page) fair game.

The main thing to remember is that until structures like crinolines and bustles were invented, except for the paniers of the 18th century, the petticoat had to facilitate and create the silhouette, and particularly the silhouette of the skirt.

In the early 1840’s, when the skirt had just reached the natural waistline, petticoats were worn one at a time, or maybe two in winter. Since drawers had just been invented and were not widely worn, many petticoats were quilted and made of multiple layers for warmth and modesty. As drawers became more popular, the quilted and multiple petticoats were reduced in weight and size, but then stiffened.

Stiffening early on was made by adding layers of tucks, which worked not only in making fullness, but also increased the thickness for warmth. A tucked petticoat of the 1830’s and ’40’s achieved a narrow rounded shape and moved like a bell going “ding dong”. The waistbands were wide and high to reduce fullness at the waist, as a narrow waist began to take emphasis:

Not every petticoat of the 1840’s was elaborate or structured. It is most likely pioneer and Western women made themselves and wore a simple petticoat of plain cotton muslin, especially if they were wearing drawers. Ones like these would be easy to store and wash along the trail, and could be used for other things as they wore out, like menstruation aprons.

As the 1840’s turned into the 1850’s, the skirt continued to widen, and the bodice to shorten. To get the fullness, ruffles were added to the bottom in addition to tucks, cording, and wire.

It was bound to happen that someone would expand the idea of wires and horsehair into a tape and wire or metal contraption called the crinoline hoop by the end of the 1850’s. It started as a “matinee skirt”, or a structured contraption that looked a lot like the corded and wired petticoats of the 1840’s, but added industrial strength. This allowed women to wear only the “skirt” plus one lighter petticoat over it to hide the divots and wires.

Once the crinoline was invented and widely used by the end of the 1850’s, the cords and ruffles came back in full force, but this time to emphasize shape in key areas of the skirt like the bottom and center. The cords and tucks were only augmenting the structural support.

Throughout the timeframe, and in 1846, any or all of these would have been worn. Which and the type of stiffener would have depended on her location and access to materials; more likely on the ast would be the new crinoline and extreme stiffeners. In the west or with the pioneer, it would be very simple with some stiffening, but not to excess. It’s more likely they would have retained in the West multiple layers and quilted layers for warmth or seasonal variation. It is also likely they would wear drawers and a lighter petticoat for function.

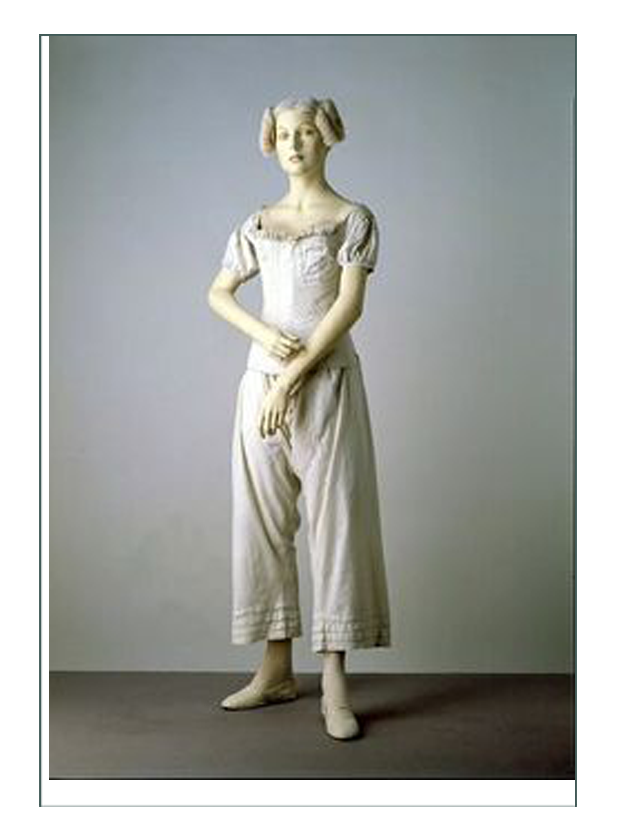

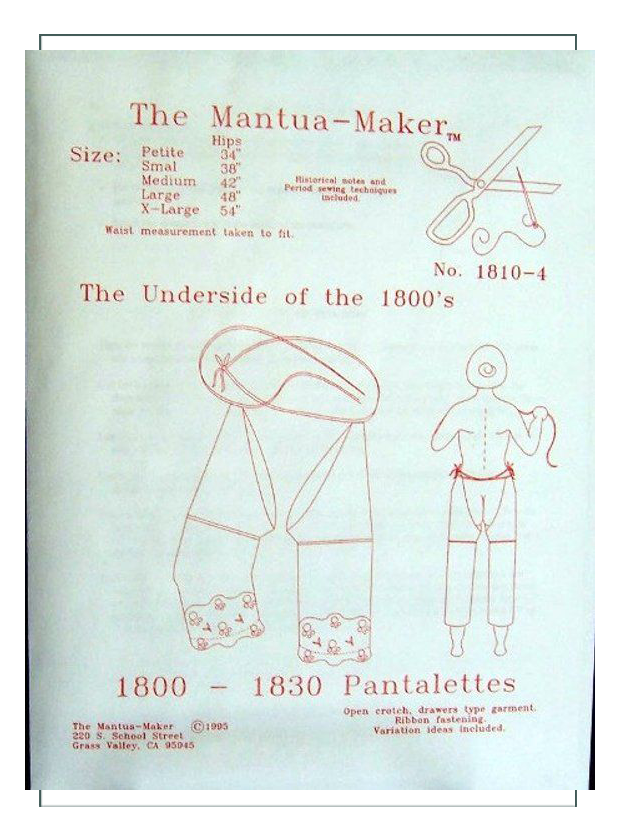

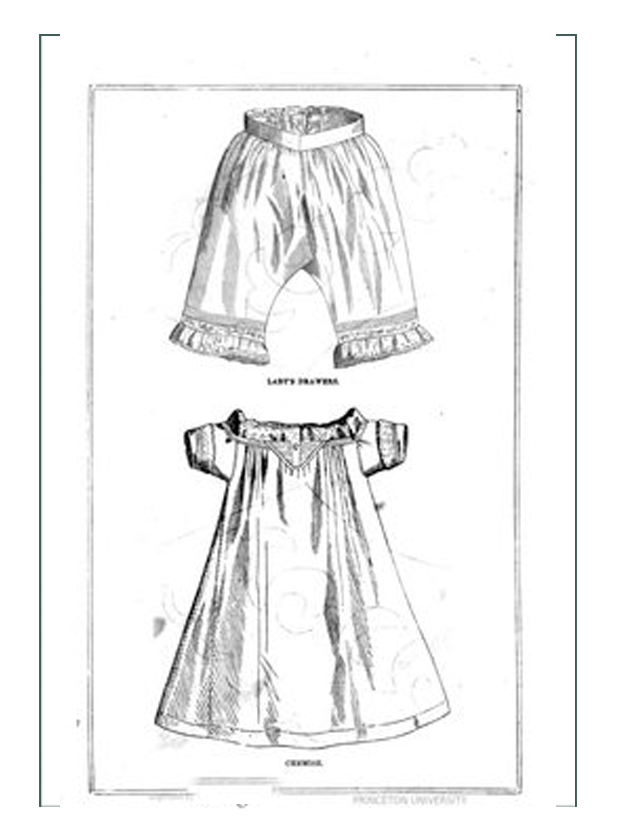

Drawers/Pantelettes

1848 was the Early Victorian Era, and the early 1840’s were a transitional time as we have seen for petticoats and corsets. Regarding what was worn “at the bum” however, it was a time of innovation.

Up until about 1836, women wore NOTHING underneath their petticoats except a shift or chemise. The terms were used interchangeably depending on if you were in England (shift), or France (chemise) for a time, as were the terms “drawers” (English) and “pantalettes” (French). Each of those terms could mean any number of garments, especially in the United States where influence from both countries was felt. It is commonly accepted now in referring to the Colonial era as wearing “shifts”, and the Victorian “chemise”. Regarding the lower half, either term is acceptable.

The first “pantelettes” originated in France it is assumed, and they were worn on a pair of suspender like straps over the shoulders, and not around the waist. Because these were introduced in about 1810 when the long straight line of the early Regency was still popular before skirts began to widen, it was necessary to reduce bulk around the middle. The waistline of gowns at that time were under the bust, so there was no desire to wear something around the waist itself.

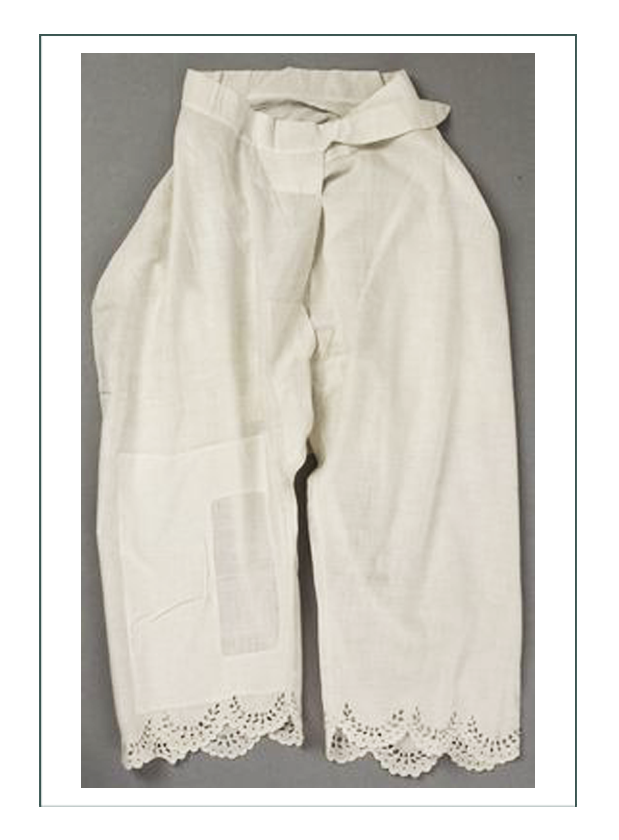

In the mid 1830’s, with the skirts wider and stiffer, and the waistline dropping towards the natural waist position, a new and short type of drawer was introduced in lady’s magazines as simple patterns that could be made at home out of any materials on hand. The favorite in the US became American sourced cotton as, the country led world production of cotton by 1820, so it was cheap and readily available to any woman.

While these would seem to be the best to our modern mind, one must remember they were wearing corsets at the time which were longer than the waist, and becoming more structured and more tightly laced. That meant the closed (meaning no gap to pull open to use the necessary) drawer had to be pulled down; nearly impossible if worn under the corset. As the waist of the skirt and petticoat reached the natural position, and the smooth long bodice was introduced by 1840, wearing the closed drawers over the corset meant bulk.

Taking a clue from the French boudoirs (the French seemed to always lead boudoir and high fashion even with Victoria leading worldwide fashion), the “split” or “open” drawers was invented. Like the term “pair of bodys”, it was always called in plural – never “drawer”, but “drawers”.

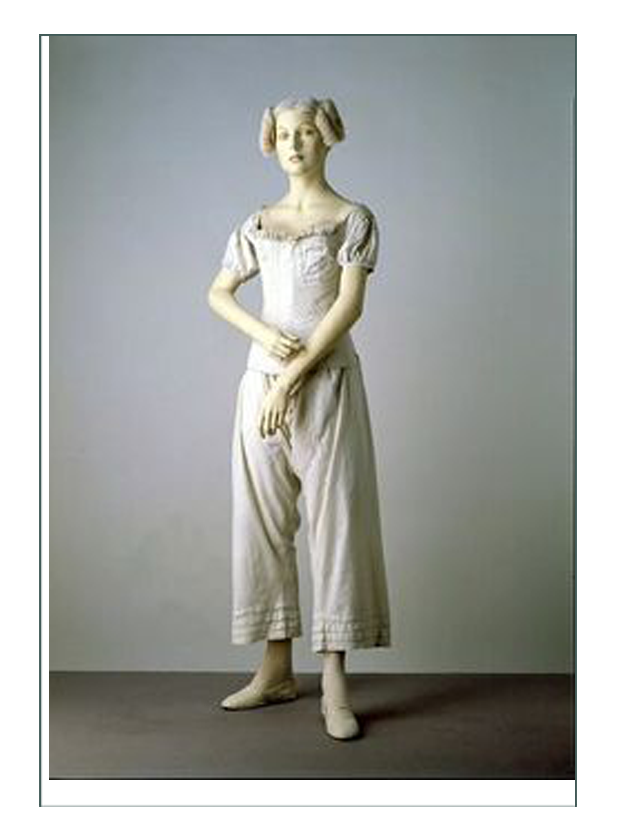

The 1840 versions, still not widely worn except in places needing them for modesty or warmth such as with pioneers, were still long with a vertical silhouette, flat and wide waistband to reduce fullness, and minimal fullness through the hips. These early drawers were split, and were ornamented much like the accompanying petticoat with tucks, broidery lace, and cording, but not ruffles (yet).

They were simple, basic, somewhat plain. Some buttoned and some tied. At this time closure were generally center front. As the desire for smaller waists progressed into the 1860’s, closures would move to the sides and always button like a flap. Drawers at this time were worn under the corset always. It would not be until the late 1880’s that the drawers would be worn over the corset when the gored skirt was introduced.

The shape and design of drawers always worked to maintain the desired silhouette of the outer garments.

Through the 1850’s, the style remained straight, but fullness and weight was added at the bottom as the drawers continued to elongate as the skirts got longer. They were still minimal on top with an effort to reduce fullness at the waist. By the 1860’s, fullness was desired just below the waist and all the way down, as long as it was not AT the waist, so the long drawers remained popular, but ruffles and fancywork were added at the bottom.

Chemise/Shift

Drawers and chemise were generally sold and worn together as a “set”, or at least somewhat coordinated with each other and the petticoat. These were simple garments easy to sew on one’s own, and cheap to buy from a catalog or store, although at this time even the WORD “leg” was forbidden by most society, so they would never be displayed in a general store.

As illustrated above, undergarments reflected and created the desired silhouette of the day. Coming out of the very low Regency bodices with their puffy sleeves in the late 1820’s, the chemise was a very plain garment with slightly full sleeves and an adjustable neckline by tie string.

By 1840, with a “bertha” collar and sleeves dropped over the natural shoulder, the chemise had to follow the shape too, or it would be visible outside the dress. A new shape of drop shoulder was created, with buttons instead of ties, and the start of fancy work in the form of lace and broiderie on the top only. The bottom was left the same as the Regency fashion with a simple hem and small gores, as bulk through the middle was still undesirable with the waist of the gown at the natural waistline by the mid 1840’s.

As the skirts were dropping to ankle or floor length from the above ankle position of the mid 1830’s, so did the chemise, as it was worn under the corset at this time, and if it was too short, it would pouf out at the hips. Later that would be considered an asset, but with the long tapered front bodice, a longer and tapered chemise was still desired in the mid 1840’s.

By the 1850’s, like the drawers, the chemise had lengthened to high calf, and was become more ornate. The shoulder continued to drop so that any fullness was well below the natural shoulder line. It was a difficult fit to keep it from falling off the shoulders, but this design allowed a woman to wear the same chemise for evening wear with low shoulders, or day wear which covered the shoulders, but still had a dropped seam. As with every era, the shape of the sleeves augemented and assisted the growing fullness of the outer garment’s sleeves.

This modern sewing pattern exemplifies the 1840’s into 1850’s chemise and drawers.

A few extant examples of 1840’s and 1850’s chemises (first one is a modern replication). Note the similarities in the 1 1/2″ facing around the neckline, position over the shoulders, different types of sleeves, and center drop that has fancy work and typically a button closure in front. Most did not have ruffles or fullness at center front, but rather “swooped” down low so that it would not be seen under a low evening neckline.

Note also that almost without exception, these were made of a lightweight and almost sheer cotton fabric in white or bright white that could easily be washed and bleached. Cotton by the 1840’s was readily available and cheap in America and the American west. Women made their own cotton crocheted laces, as thread was available too. Later fancy work would be mass produced and readily available too.

Today, one can find antique garments for sale feature beautiful tatting and crochet on undergarments. Many of the delicate cotton fabrics have deterioriated (as some of the American cottons were not that high in quality), but the laces remain on the market for sale with fragments of the original chemise clining on.

By the 1860’s, the shift might be long or short, but the addition of a corset cover in much the same design and construction would be added to the undergarment package. In the 1840’s and 1850’s, a corset cover was somewhat an optional item and not widely worn as they would be at the end of the century.

Even in the West 1845-46

Examples of 1846 specific dresses and outer garments follow. Note that the silhouettes, shapes, bodices, skirts, and fabrics are consistent throughout regardless of whether it is “high” or “low” fashion; pioneer/settler or from the east coast or Paris.

Look for the long center front bodice, drop sleeves, low horizontal neckline, long sleeves, somewhat full but narrow belled skirt with stiffener at the bottom, bonnets (prairie for work; straw for dress up), and unique hair of the day. Note how the corset and petticoat are the key to obtaining and keep these silhouettes:

Garments in museums from 1844-49

1850s

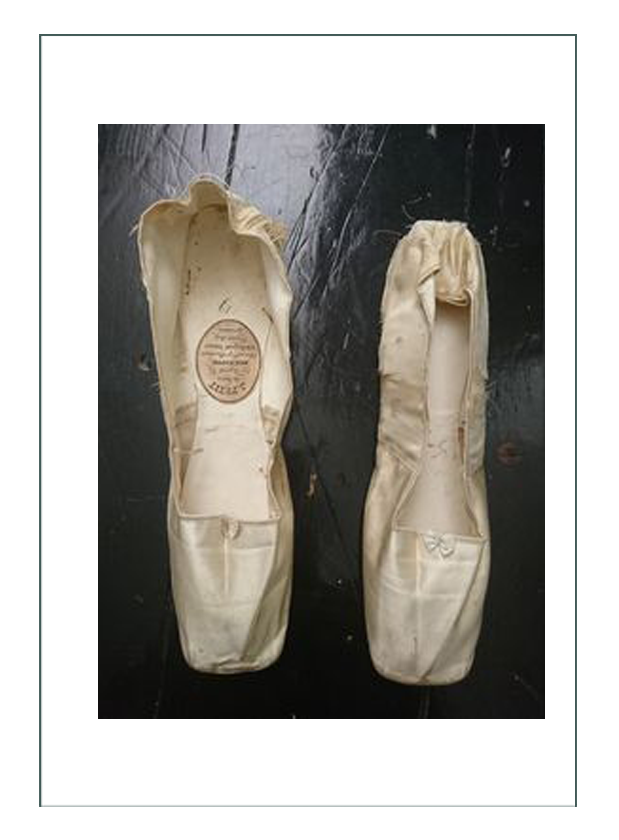

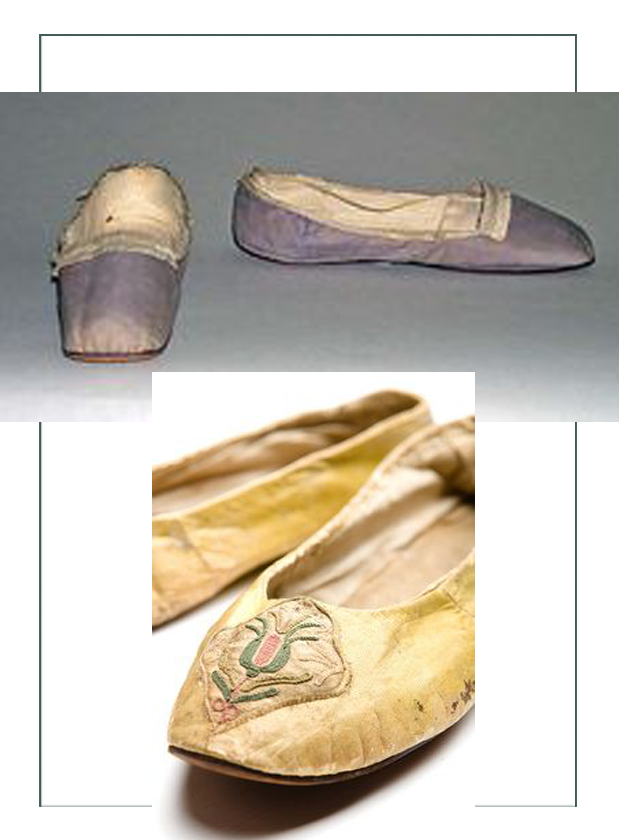

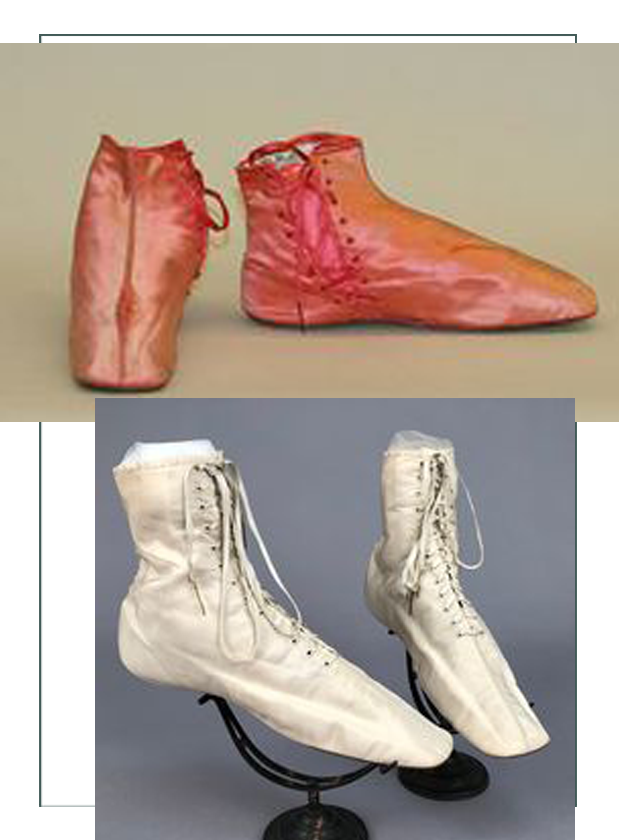

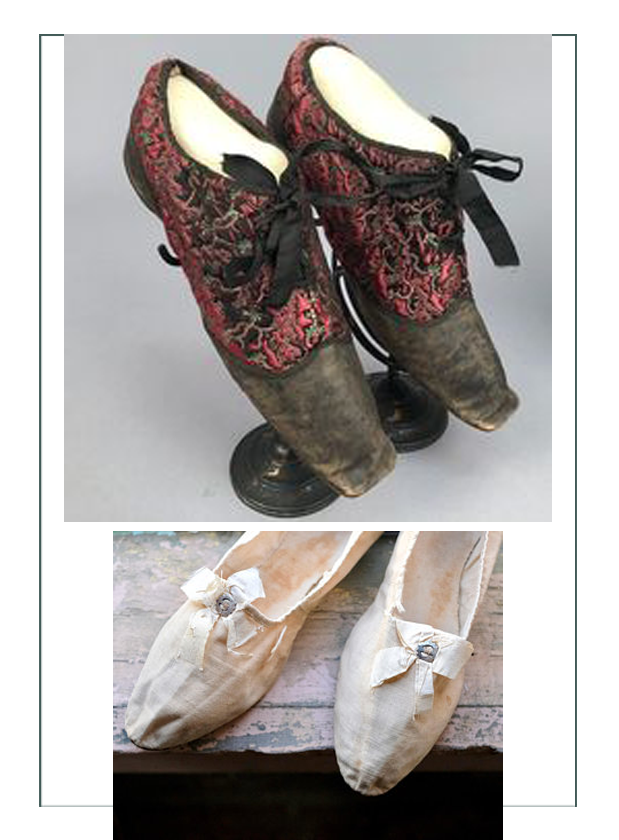

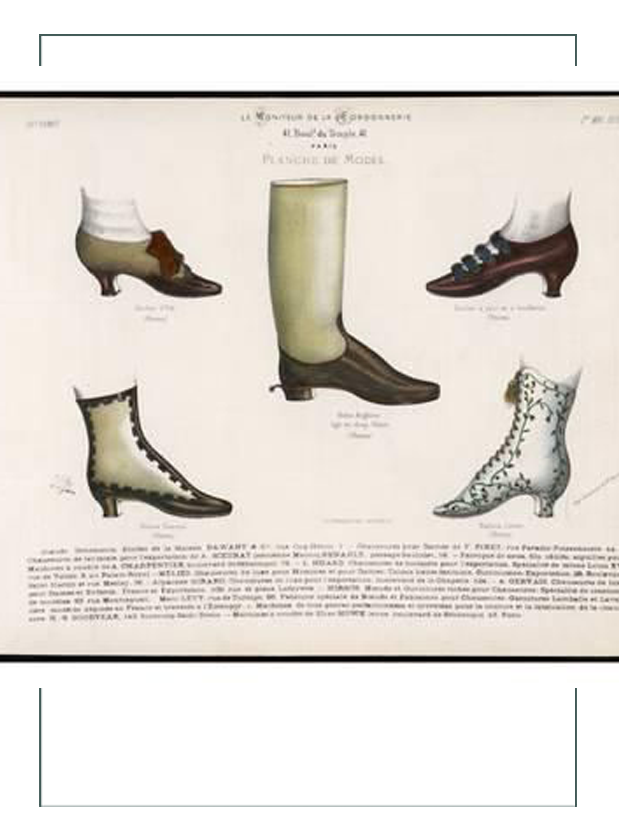

When one thinks about Victorian footwear, one pictures a leather black boot that buttons up on the sides, or laces up the front. The zipper would not be invented and put into a hiking boot until 1922, and there was no elastic, so the construction and fit of footwear had to have flexibility to get it on and off – especially considering “right and left” shoes would not be invented for another decade.

Yes, that means a boot or shoe would fit either foot in the 1840’s. Of course, since only natural materials were available – hides, leather, silk, fabric – as plastics and petroleum products were not invented either, they would stretch and form over the foot to make a kind of “left and right”, but they were not build nor designed as such.

The 1840’s built on the concept of the Regency slipper, which was very much like today’s ballet shoes. They even had the same square toe as a ballet shoe, and sometimes would be stuffed.

The Regency slipper might have a heel tap (the small crescent under the heel), but generally did not have a hard sole. It was made of silk or fabric with some sort of paper stiffener like cardboard. You can see a general progression towards a show made of more durable material like thick leather. As the 1830’s progressed though, stronger heel taps and leather soles were added. The shoes below made of kid and/or silk are currently on sale for $800-$1000.

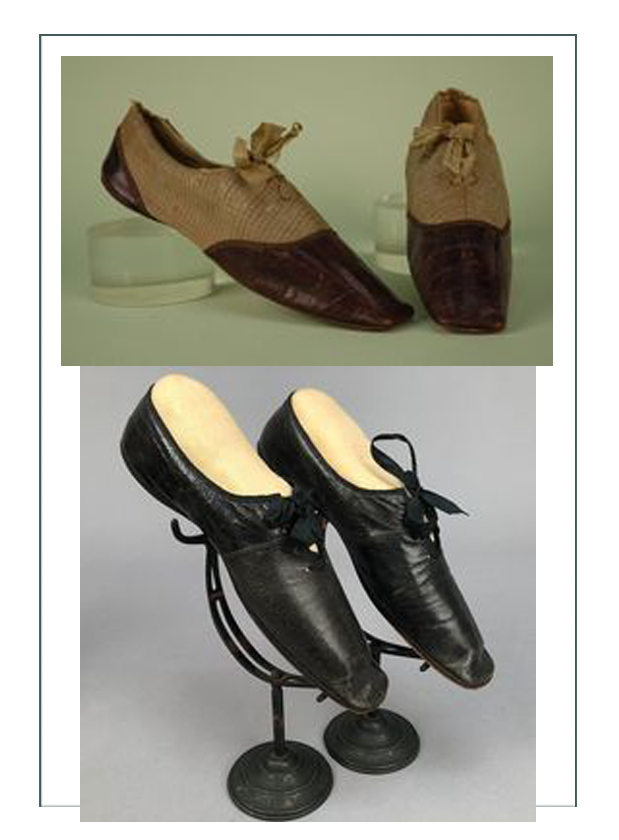

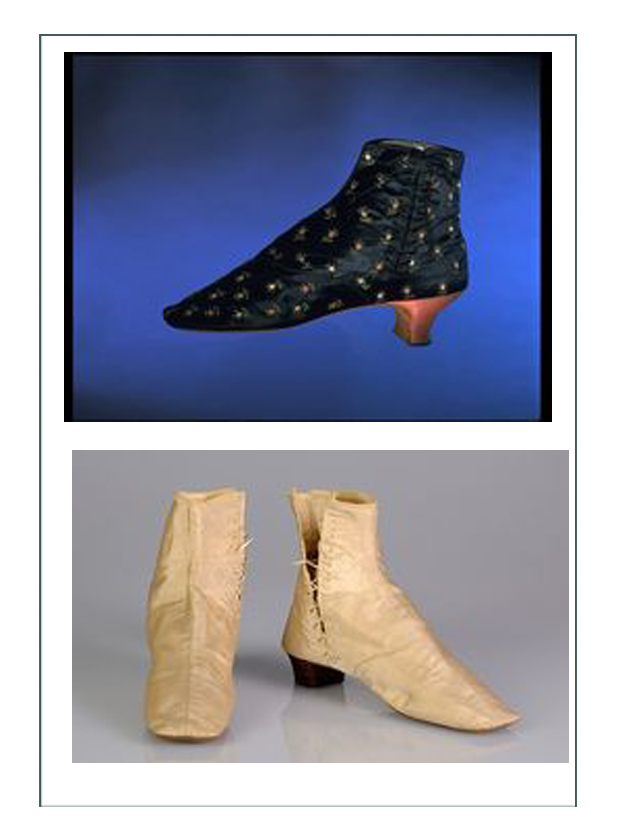

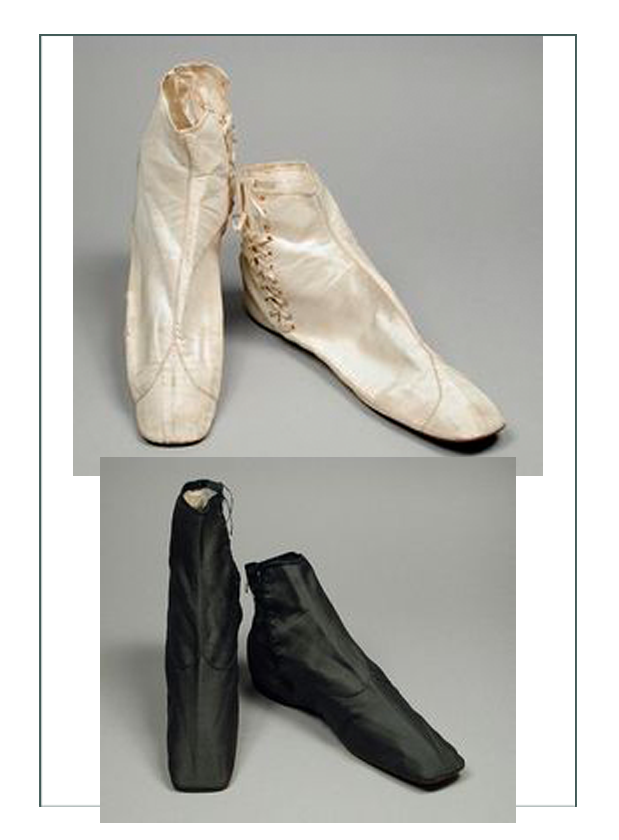

By the 1840’s, the low, ballerina type shoe had grown to encompass the ankle and lower calf. It became a “boot”. While many were still made of silk or other fabrics, most, and those of the every day woman, were made of leather that was softened so the “boot” was more like a cozy slipper. Since there were still no “left and rights”, the leather had to be kid or something soft or it would hurt the foot.

Lacing in the mid 1840’s was typically done on the inside or outside of the “ankle boot”, and kid leather was still a favorite. As the 1850’s progressed, center front lacing became popular, and the leather used was thicker and stiffer. By the mid 1850’s, a thick and durable sole with a heel was added. These had a replaceable heel tap since the leather was still not that strong.

The sole and tap were installed separately, but by the 1860’s the sole and heel were one piece together, and the right and left had been introduced. Right and left shoes became readily available in about 1860 when the techniques of shoemakers changed to make the cutting and construction of a right and left possible. At that time, a pair of shoes or boots was custom made to the person’s right and left foot as separate pieces and not built as an identical pair, although they were sold as such.

By the end of the 1850’s, more boots had heels and heel taps. The sturdy “block” type of heel would lead into the next fashion of the front lacing tall or high calf boot that is more widely associated with the Victorian era.

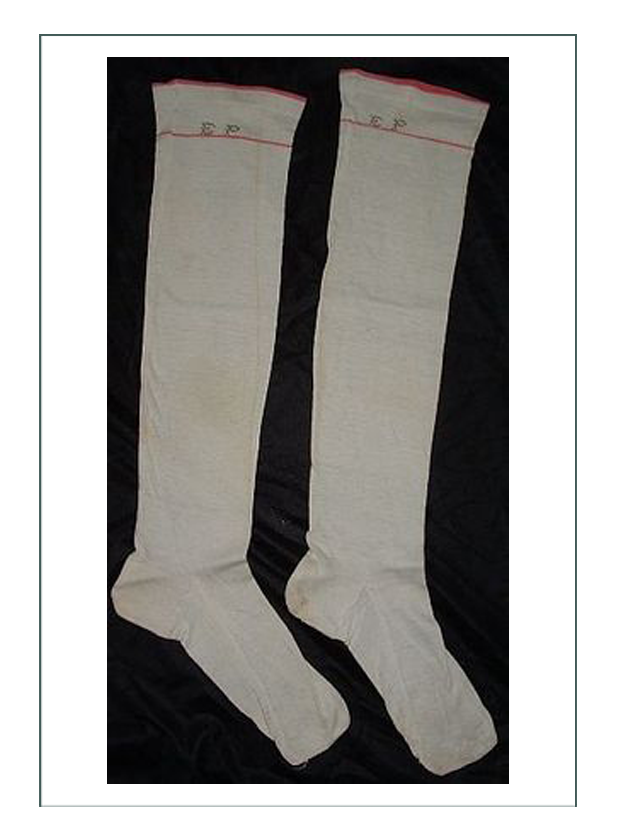

Stockings

From the 1700’s until about 1900, women wore over-the-knee stockings with garters. There were many, many types made of every kind of thread or yarn: wool for working and warmth, silk for special, cotton when available, and blends of woven commercial or hand knit fibers. All were left white or natural to the type of material used, such as the grays and browns and whites of a sheep, or the various whites and yellows of natural American cottons.

Some were dyed with the same natural colors, and imported stockings such as silk were dyed overseas using the same techniques as for fabric.

There were integrated patterns using same color and same fiber, as well as woven and embroidered fancy work, lace, or intricate “clock work”. A most typical favorite was to have a contrasting color interwoven into a pattern down the outside of the calf.

While stockings got longer so they could be clamped into hooks sewn onto the longer corsets of the 1880’s, for the most part they remained over the knee and were held in place by a garter. 18th century garters could be as simple as a strip of fabric tied around the leg, or a complex reticulating metal looped contraption that dug into the skin and made it bleed.

Some were woven so there was a tight bias band on the top that could stretch to put it on, but still hold to the leg. Most were tied with something.

Today we wear over the knee stockings that have lycra (rubber product) woven in that makes it “sticky” to the leg and holds tightly all the way to the top so garters nor clamps are needed.

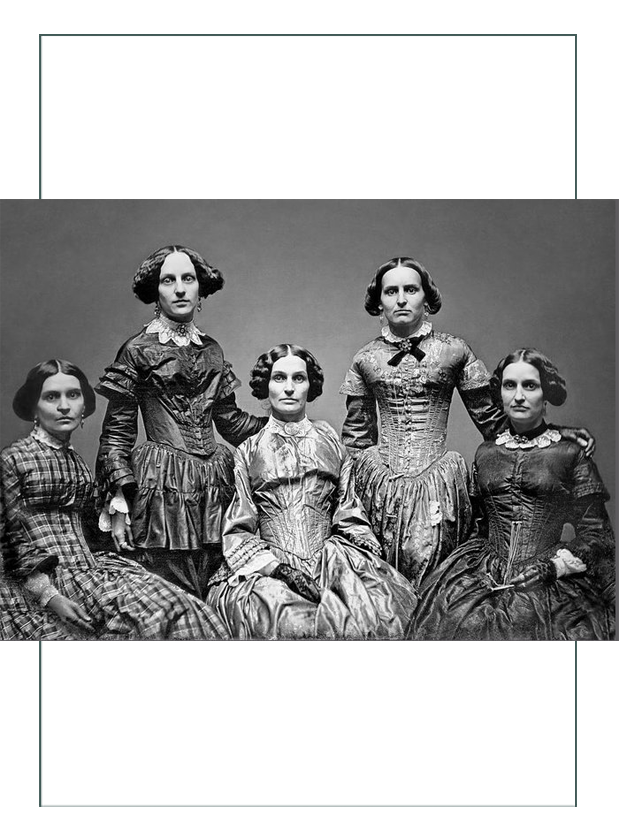

Real Women of the day

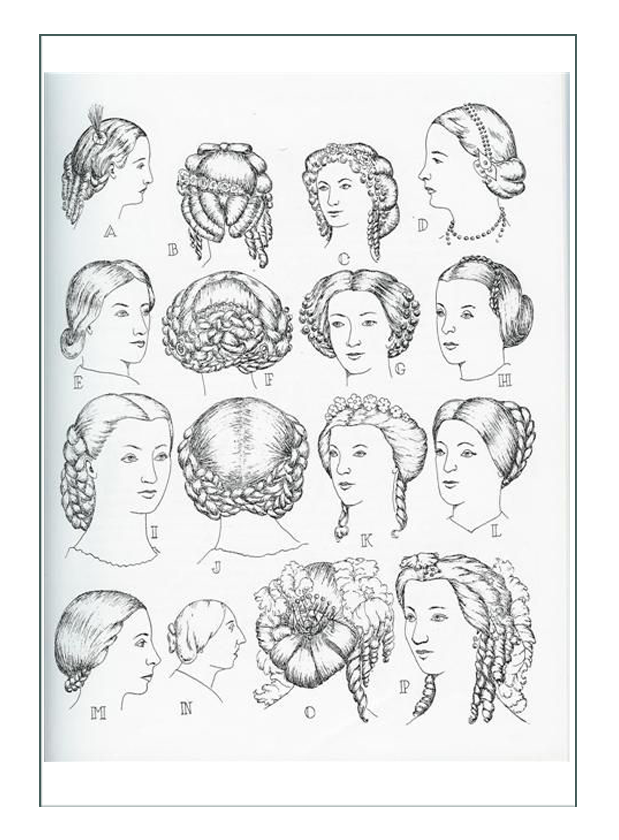

The hair of the 1840’s has been of interest to historians and interpreters more than probably any other era than Regency. This is because most modern people really don’t like the style.

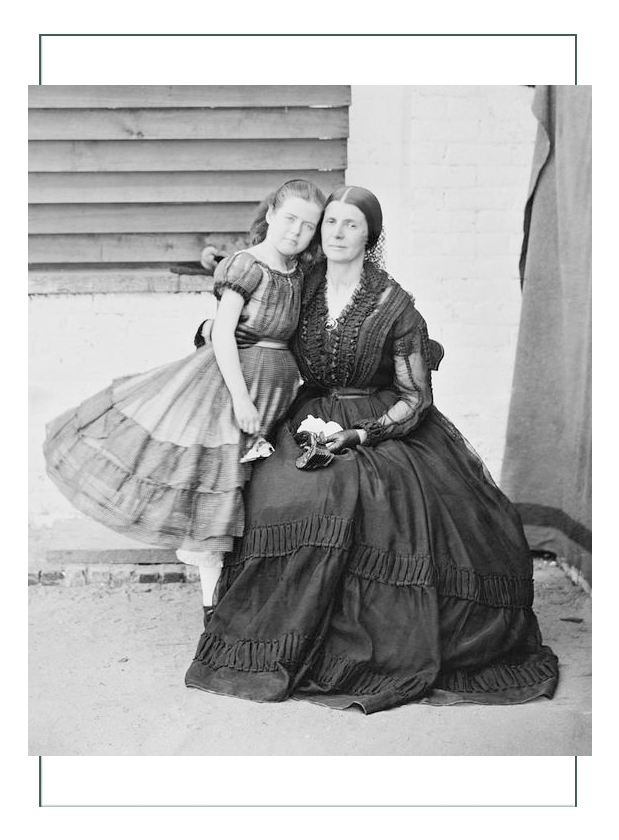

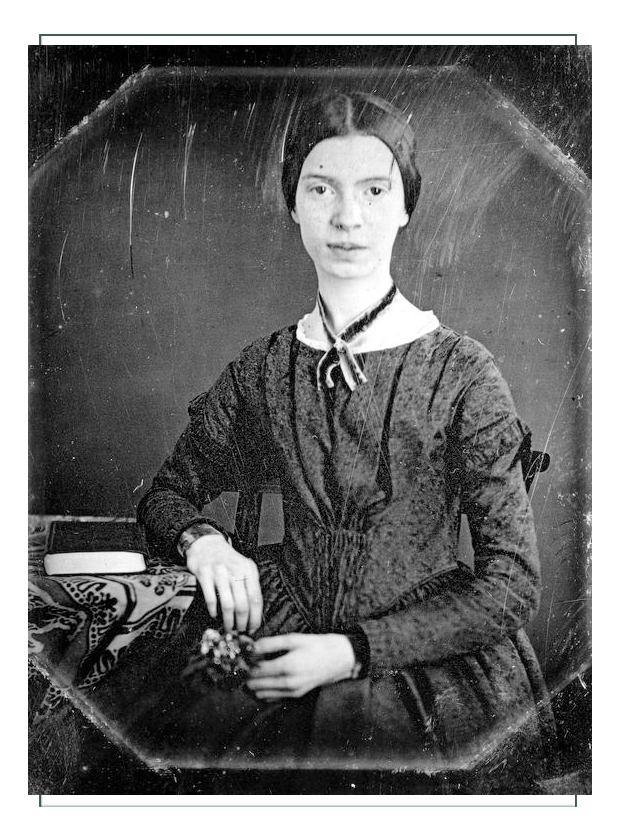

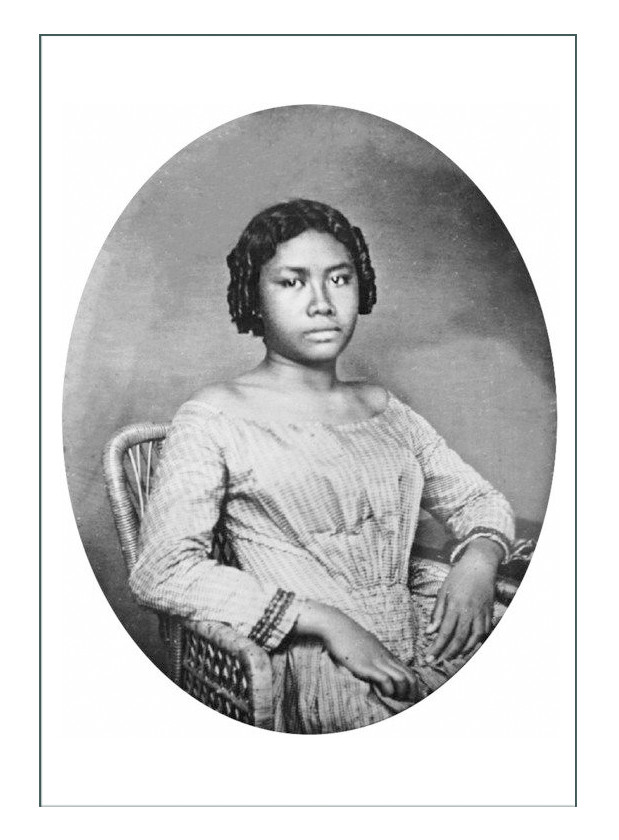

As the photos and portraits of real women of the 1840’s and ’50’s show, the predominant hairstyle for women of all classes and locations was a type of braid wound tightly into a “cinnabon” and worn low on the back of the head or the sides.

The looping braids over the ears or “spaniel ears” were very popular as directed by Queen Victoria. All her staff wore them.

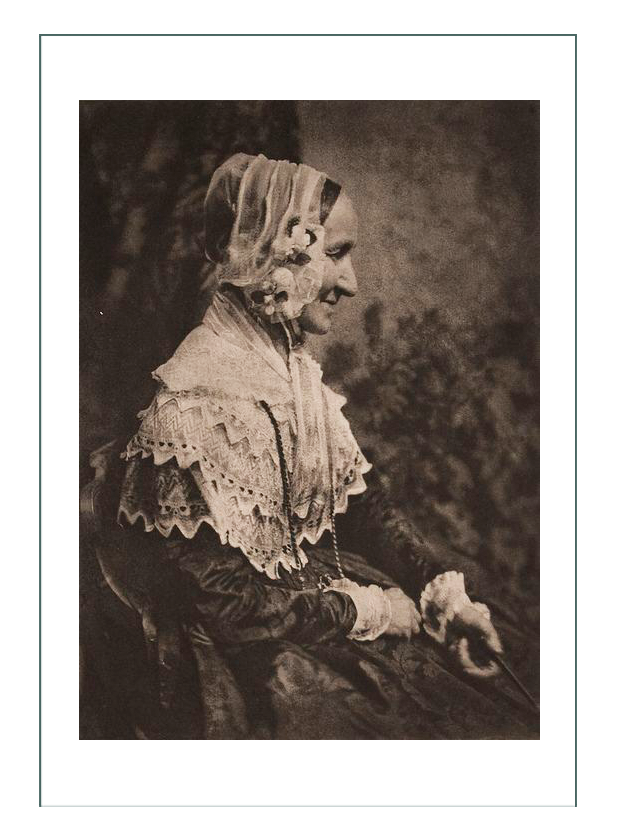

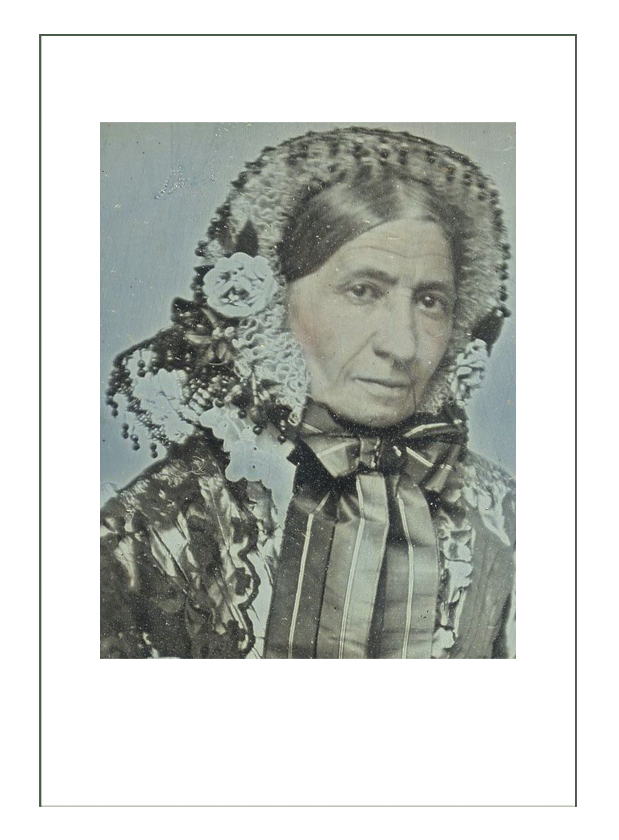

Older women who had lived through late Colonial and Regency eras, still clung to a type of “lappet cap” for home wear. These were generally somewhat sheer in this era, and allowed women to not have to wash and braid their hair.

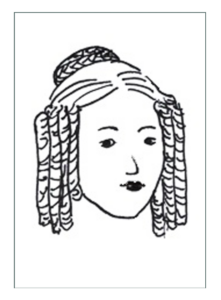

A few of the corkscrew curls around the face were still worn as a carryover of the prior era, but the very smooth, side/center parted hair with the looping front sides was still the most popular for younger and fashionable women. There were many odd configurations of the looping of the braids as split on two sides of the heads as per the last two photos.

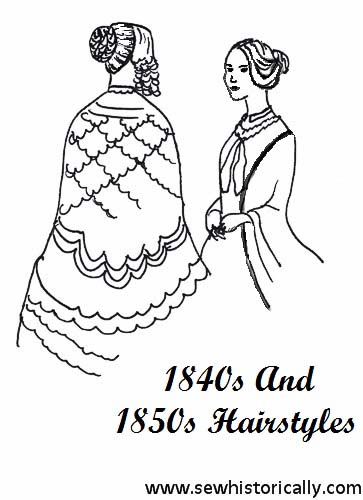

We present this from http://www.sewhistorically.com/1840s-and-1850s-hairstyles/ word for word, or go to the link to see their original:

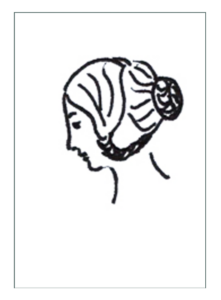

The typical hairstyle of the 1840s and 1850s was a bun at the back of the head with slight variations. At the beginning of the 1840s the bun was worn low, in the later 1840s it was worn high at the back of the head, and in the 1850s it was again worn low in the neck. The hair was parted in an Y shape, which can be seen in this 1854 painting. The bun could be just a twisted strand of hair; but the hair could also be braided (-> my tutorial) or rope braided before it was put into a bun. For evening wear the bun was more elaborate.

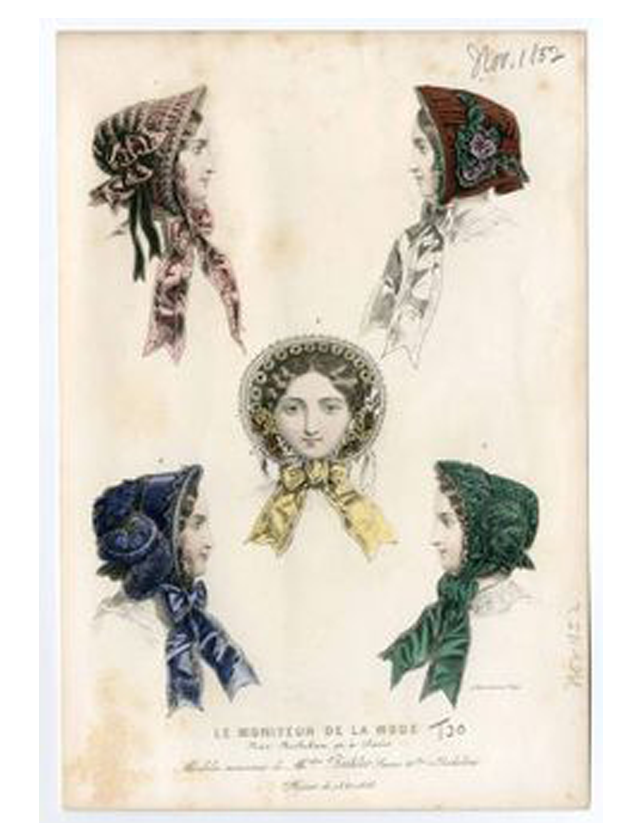

During the day, the hair was usually covered: indoors with a day cap, and outside with a bonnet. The day cap (other names: morning cap or breakfast cap) was worn worn in the early part of the Victorian era by all women (young, unmarried and married women), later just by married women, and since the 1860s or 1870s mainly by older, married women. The front hair was worn in curls or loops.

Early 1840s hairstyles (low bun)

‘The front hair in bands, with or without the ends braided, and turned up again, or in long full ringlets. The back hair is still worn dresses as low as possible at the back of the neck, in braids, chignons, and rouleaux.’ (1840, Godey’s Lady’s Book) Here’s an 1841 painting and 1842 painting of Queen Victorian wearing a low bun with braided loops over the ears.

Mid to late 1840s hairstyle (side ringlets, high bun)

The hair is still being worn in full ringlets on each side, the back part tastefully arranged in plaits caught with a handsome comb’ (1843, Godey’s Lady’s Book). Here’s an 1844 photograph of a woman with ringlets and a braided bun worn high on the head. Here’s a similar hairstyle in a painting from 1848. In 1852, this hairstyle was still worn.

Mid 1840s to mid 1850s hairstyle (loops over the ears)

Here’s a 1845 photograph of a woman wearing hair loops covering her ears. She also wears her bun a bit lower as in this 1849 painting of a similar hairstyle. The bottom of the hair loop in this 1850 painiting is nearly parallel to the floor, while late 1850s side loops of hair are more sloping. In 1855, the same hairstyle was worn, but with the bun a bit lower. And a variation of the hairstyle: this woman wears a braid over her ears (1853 painting).

A

B

C

Where Hair goes, So Goes the Hat

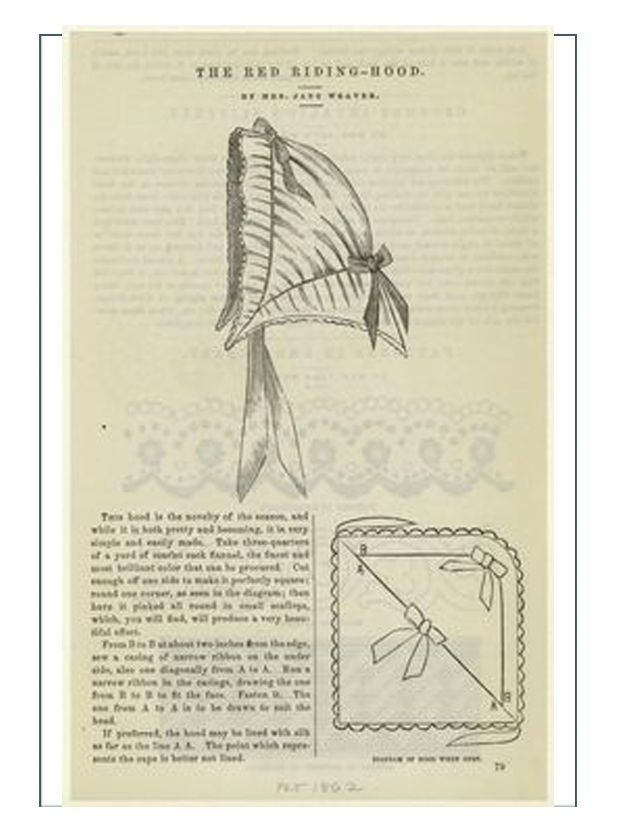

It is important to note that in any fashion era, the hair determines the shape of the bonnet. As hair goes wide or high, so goes the bonnet. In 1846, with hair piled on the sides and low in the back, of course the bonnet would have a crown that was low and deep, and wide in front so the hard work of the braids or curves would show.

Rural or Urban?

The type of bonnet worn at this time depended on where a woman lived and what she was doing. Predominant in the West was the need to protect ones head from the elements: to stay warm in the cold, protect from the wind, keep sun out of one’s eyes, and keep cool in the heat. On top of that, as the 1850’s approached, was the rising concept that a woman was demure and weak. She covered herself from head to foot in order to appear to be tiny and diminutive which was the ideal of the day.

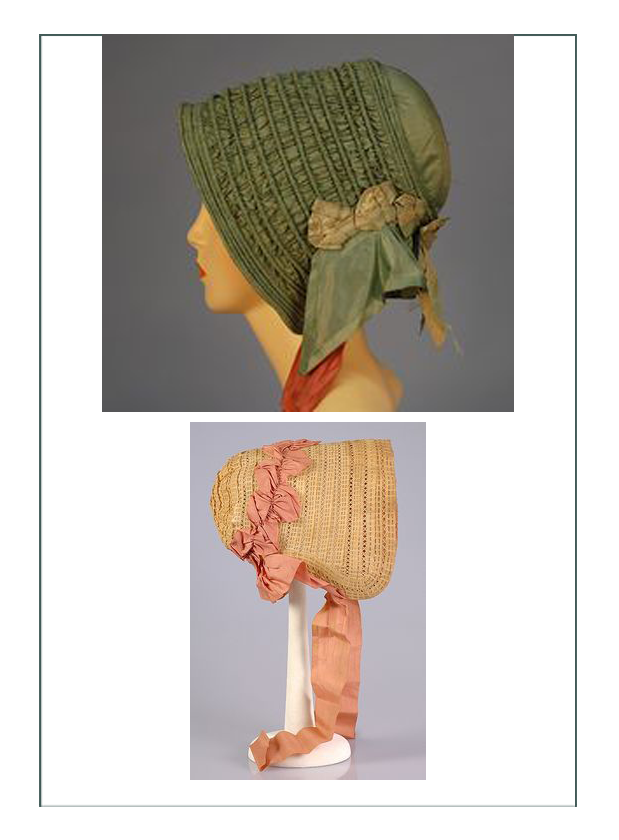

This translated itself in the types of bonnets worn. All practical to some extent, they all had the same characteristics as the Regency bonnet: crown, brim, bavolet (curtain in back or neck covering), and some sort of adjustment tie or lacing.

This complete covering of ones neck from the gaze of men, served double purpose to keep the neck from being sunburned.

There were many types of bonnets worn by pioneers and settlers. Which kind depended largely on the season, work being done, availability of materials, and ability of the woman to make them herself. The “prairie bonnet” might be slatted, padded, roved, folded, wide brimmed, narrow brimmed, or flat crowned but they all had: covering by the brim of the whole face with shielding from the side, adjustable soft crown of some sort, bavolet or neck curtain.

Fabrics for the prairie bonnet were of whatever was available, and often all mixed up with different fabric scraps used for different parts. It was not unusual the bonnet didn’t match anything, including itself.

Examples of several types of 1840-50’s prairie bonnets are below.

Prairie Bonnets

Wadded (filled with wool roving or cotton fill):

Quilted: with cotton or wool:

Slat: flat inserts for rigidity:

Slatted and Quilted: reinforced brim with insulation:

Reinforced brim:

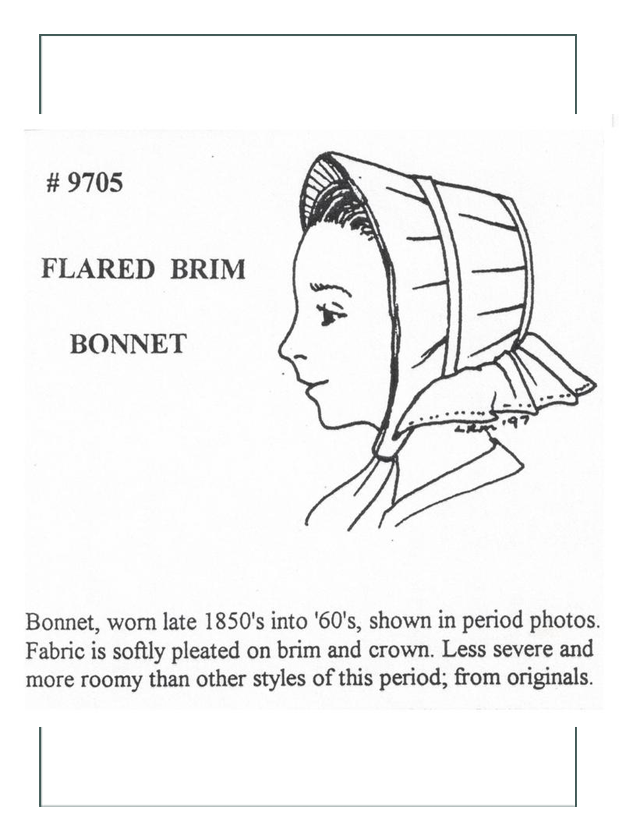

Flared Brim & Fanchon Bonnets

For going to town, dressing up, or not working, because the “diminuitive woman” had to cover herself up as much as possible in public, a version of the prairie bonnet evolved into something like a Regency bonnet with a small brim.

This flared brim bonnet would evolve in the 1860’s into the Fanchon: a wide coned shaped brim with scant back which still looked somewhat like the prairie crown but was made stiff, and with ties for the neck and a short bavolet covering the neck:

Some flared bonnets were very simple and of straw with a silk flower or two. Some were corded like a petticoat and stuffed or quilted. Others were covered in silk or other fancy fabrics with lots of ribbon and lace. The most basic was worn across the country, and it was a dyed straw that was shaped on a wooden form by a milliner, and decorated at home by the woman herself. She would change decoration to match her gown or to adjust to the changing fashion or the time of year.

Hybrid Bonnets

At the time, there were long, scoping prairie bonnets that were made rigid into a longer version of the flared bonnets. There were also flared bonnets made soft and adjustable with the shape of a flare, but the function of a soft prairie bonnet. It seems at the time, the bonnet’s function might have taken priority, at least compared to other fashion eras.

In the West or with a pioneer, she most certainly would have chose function first, so it is most likely the type of bonnet selected would have suited what she did for a living – however – it is logical most women would also have a special bonnet of some sort to wear when “dressing up”.

Click here to go to Jessica’s Design Development page (next)

Click here to go to Jessica’s Main page to see the finished project