The previous Historical Context Pages includes General Fashion History plus Colonial Fashion details of 1785. Click here to go back to that page.

Click here to see the history of Celtic weaves and fashion on Susan’s 1745 project research pages too!

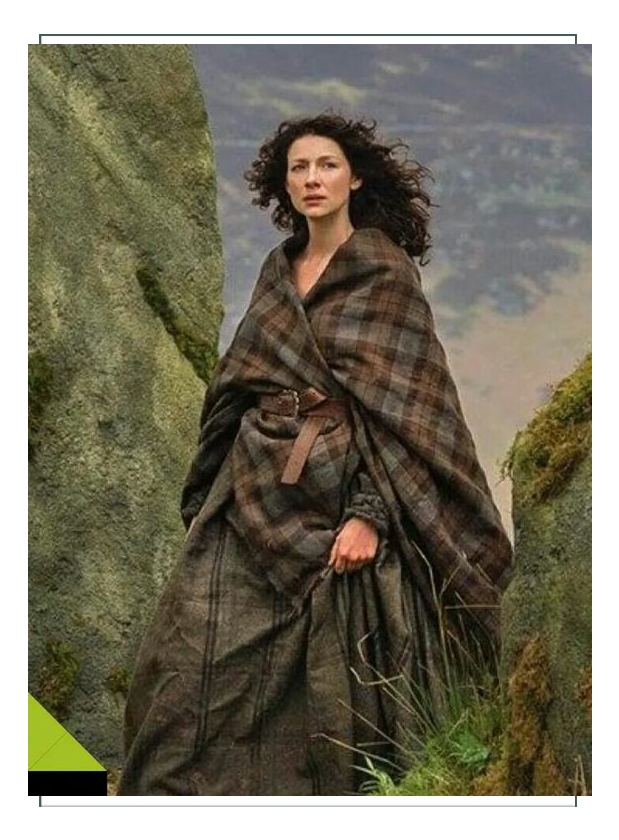

This project is based on the MacTavish gown, plus takes inspiration from the “Outlander” Series (see Susan’s research on “Outlander” by clicking here). Following are excerpts and videos from the experts describing the history, design, and reproduction of the MacTavish-Fraser and similar projects for Scottish Colonial gowns of the late 18th century.

Written excerpts from the above authors

Isabella reporting,

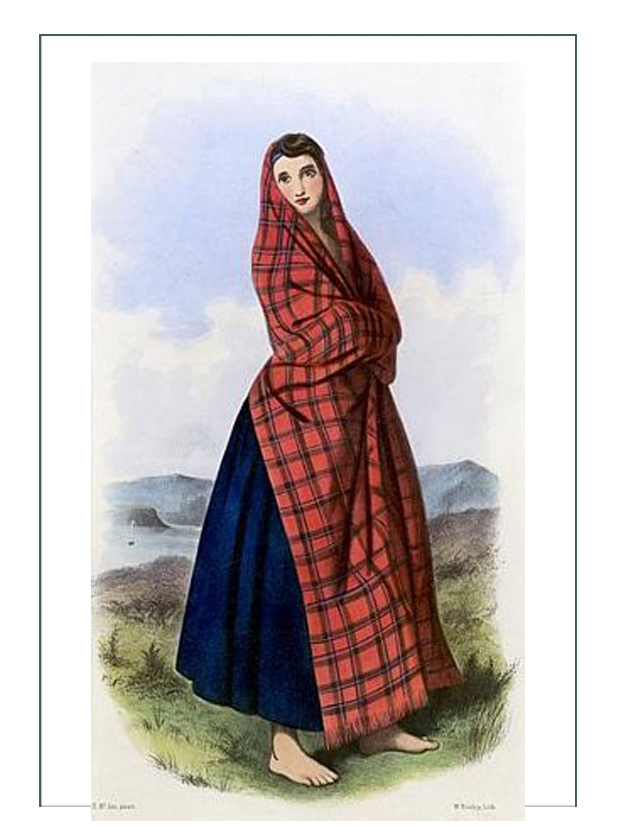

Wedding dresses are always special. Fans of the current miniseries Outlander were eagerly anticipating the wedding dress worn by the heroine, and when it finally appeared, social media was ablaze with reactions. While I’m not about to tackle whether Claire’s gorgeous, glittering costume was appropriate either to 18th c. Scotland or to the book (although here’s a thoughtful blog post with pictures, defending the costume designer’s choices), I decided it’s the perfect time to share a wedding dress that was undeniably worn for an 18th c. Fraser wedding in the Highlands.

Alas, I haven’t seen this dress in person – it’s in the collection of the Inverness Museum and Art Gallery – so my observations are based on photographs and other sources. The dress was made around 1785 for the wedding of Isabella MacTavish to Malcolm Fraser, both of Stratherrick in the Scottish Highlands. Like the Elizabeth Bull wedding dress that I wrote about earlier this summer (see here and here), this dress has also been worn by successive generations of Fraser brides.

The dress was not made by a skilled mantua-maker. The style is simple, and a little old-fashioned for its time – though apparently there’s allowance beneath the back skirts to accommodate a trendy false rump for extra volume. Nor is the stitching the work of a professional, with mismatched plaids and awkward seaming. For more details about the dress’s construction, including sketches, see this article by Catharine Niven, curator at Inverness.

What fascinated me was the possibility that this dress, much like the Bull dress, had been made by the bride’s family, and perhaps by the bride herself. It’s unlikely that any scholar will ever discover the true maker’s name, but it’s tantalizing to imagine several women collaborating on this single, significant garment.

And it was significant – not only because of its ceremonial purpose, but on account of the fabric from which it was stitched. In this article, scholar Peter Eslea MacDonald notes that while the the dress was made around 1785, the wool plaid is likely much older, from c.1740-1760. Because of the amount of red dye used, this was originally an expensive and much-valued plaid. I’ve shared a number of 18th c. dresses (here and here) that were remade into new fashions, a thrifty way to recycle a costly fabric. But however beautiful the silks used in those dresses were, this plaid was different.

Traditional tartan plaids represented different clans in the Highlands, and were worn proudly. and rebelliously as well. After the disastrous Jacobite Rising of 1745, England passed laws designed to further destroy the power of the clans, and to force the Highlanders towards assimilation. As part of the Act of Proscription of 1746, the Dress Act prohibited wearing “highland clothing” such as tartans. The penalties were severe, and included imprisonment and transportation. The forbidden textiles became even more precious, symbolic of all that had been lost, and were carefully hidden away for safe-keeping far from English eyes.

The Dress Act was finally repealed in 1782. This dress was made soon afterwards. The true story of Isabella MacTavish’s wedding dress may be lost, but how easy it is to image a grandmother reverently bringing out this MacTavish clan tartan that she’d hidden nearly forty years earlier, and giving it to the bride for her wedding dress – a dress that would have symbolized love, and so much more.

Highlander Specific Garments Desired

(see also the history of Celtic fashion of the 18th century)

Excerpt from TwoNerdyGirls.com:

Bestselling authors Loretta Chase & Susan Holloway Scott gossip about history, writing, and yes, shoes.

A Rare Wedding Dress for a Highland Bride, c. 1785

Tuesday, September 30, 2014

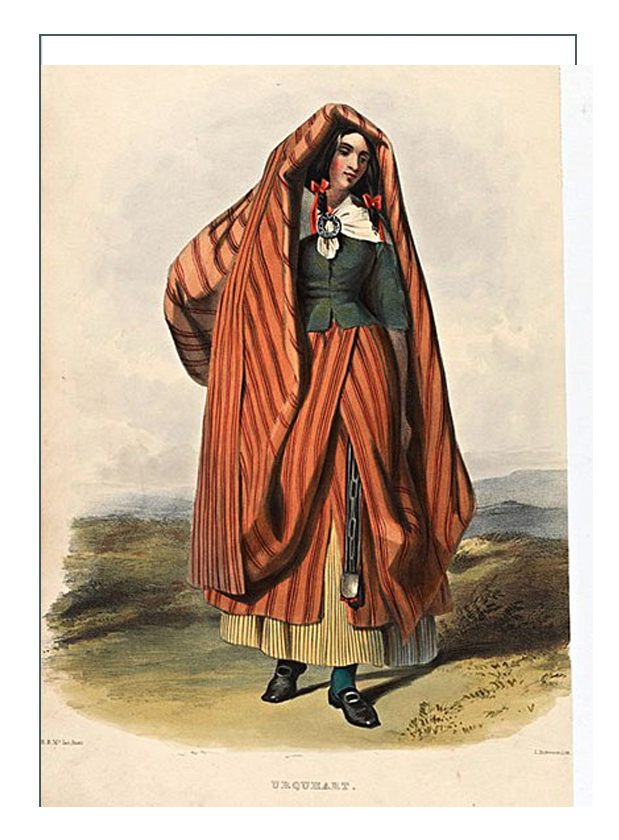

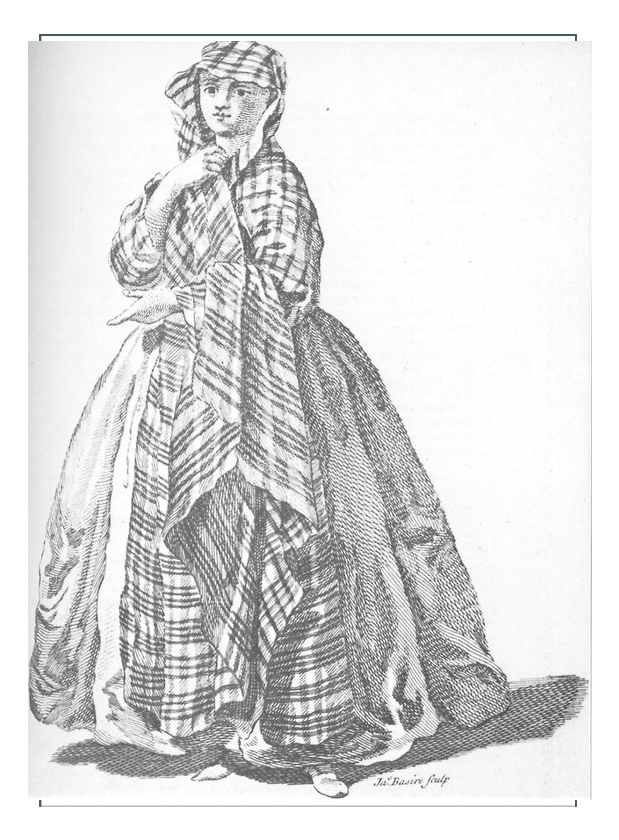

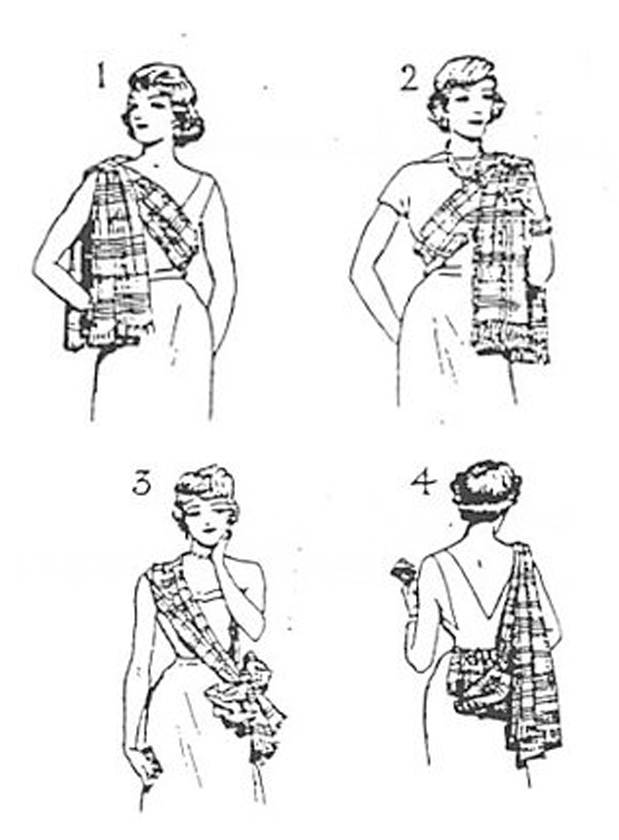

An earasaid, or arasaid[is a draped garment worn in Scotland as part of traditional female highland dress. It may be a belted plaid (literally, a belted blanket), or an unbelted wrap. Traditionally, earasaids might be plain, striped or tartan;it might be brightly coloured or made of lachdan (dun or undyed) wool. Some colours were more expensive than others. Modern highland dress makes earasaids from the same heraldic tartan cloth used for kilts.

Near the end of the seventeenth century, Martin Martin gave a description of traditional women’s clothing in the Western Islands, including the earasaid and its brooches and buckles:

“The ancient dress wore by the women, and which is yet wore by some of the vulgar, called arisad, is a white plaid, having a few small stripes of black, blue and red; it reached from the neck to the heels, and was tied before on the breast with a buckle of silver or brass, according to the quality of the person. I have seen some of the former of an hundred marks value; it was broad as any ordinary pewter plate, the whole curiously engraven with various animals etc. There was a lesser buckle which was wore in the middle of the larger, and above two ounces weight; it had in the centre a large piece of crystal, or some finer stone, and this was set all around with several finer stones of a lesser size.

The plaid being pleated all round, was tied with a belt below the breast; the belt was of leather, and several pieces of silver intermixed with the leather like a chain. The lower end of the belt has a piece of plate about eight inches long, and three in breadth, curiously engraven; the end of which was adorned with fine stones, or pieces of red coral. They wore sleeves of scarlet cloth, closed at the end as men’s vests, with gold lace round them, having plate buttons with fine stones. The head dress was a fine kerchief of linen strait (tight) about the head, hanging down the back taper-wise; a large lock of hair hangs down their cheeks above their breast, the lower end tied with a knot of ribbands.”

The “Great Kilt”, however, refers to the historical “large wrap” (féileadh-mór) which was worn in the Highlands in the 16th-18th centuries. Also called a “belted plaid”, this type of kilt is worn wrapped around one’s body with the material loosely gathered and held at the waist with a belt. Some of the belted plaid hangs down to the knees and the rest of the material is wrapped up around the upper body over the left shoulder and held by a pin to keep it in place.

The Gàidhlig word for “blanket” is plaide, and “belted plaid” is essentially saying it’s a woven, blanket-like garment that’s held on with a belt. (This is the garment that was forbidden to be worn from 1746-82 after the second Jacobite Uprising.) The modern version of the kilt, the short kilt (feilidh-beag, “little wrap”), came into fashion in the early 18th century. The (Anglicized) “philabeg” is just the lower part of the belted plaid, and was originally held in place with a belt until modern tailors stitched the gathers into uniform pleats.

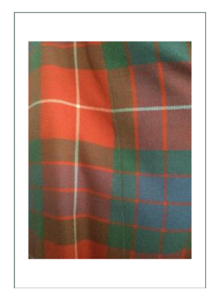

Fraser tartan

We in America call the pattern of stripes in different colors and widths which cross at right angles, “plaid”, but the pattern is really a “tartan”, tairtan (Scots), from the French tiretain, woven cloth. Tartans were sometimes woven without a pattern to them. The patterned cloth woven in the Highlands was called breacan, meaning “many colors”. As things evolved, the word “tartan” came to mean a certain pattern woven into a certain cloth.

The terms “ancient” and “modern” when used to name a tartan refer to the difference in the color depth of the pattern. Modern is darker and ancient uses lighter colors that reflect the historical use of natural dyes. The pattern remains the same in both. A “weathered” tartan is meant to look as though it has been in use for a long time, or at least pulled out of great-great granddad’s attic. “Hunting” tartans and “dress” tartans refer to the changes in color of the patterns, not the patterns themselves. In the 17th and 18th centuries, the Highland women wore arasaide tartans that were woven with a white base.

These were the “belted plaids” for the women: long flowing capes of tartan that could be wrapped around the body and up over the head (heid). In Victorian times, the “dress” tartan became associated with formal occasions because people didn’t want to wear the darker colors and thought the white-based tartan more festive.

In the mid-1800’s a book published two tartans for the MacLeod Clan, one yellow and one green. After that, Clans that didn’t have green in their tartans started weaving another pattern to include green. They became known as “hunting” due to the green hues, not that they were worn especially for hunting.

Fraser Hunting,

Ancient and Modern

In 2008, the Scottish Parliament established the Scottish Register of Tartans “in order to protect, promote and preserve the tartan”. All tartans: ancient, modern, and brand new have to be approved and registered. A true tartan has a unique thread count, pattern, and colors, and has a specific name. Historically, that meant Clan names, but in modern times anyone can design and register a pattern for a tartan.

The pattern is called a sett and was chosen on the availability of natural dyes in different areas, so each clan would have used the dyes available to them. This was the precursor to the modern-day Clan Tartan which came into existence in the early 19th century, probably with help from Sir Walter Scott. The sett is the measurement of the width of each stripe in the pattern; in modern times is it a precise thread count for each stripe.

The series of stripes that make the pattern of the tartan reverse around a central stripe (pivot). The block pattern formed by the bands of stripe intersecting at right angles is repeated throughout the material. The warp threads are set on the loom and the weft threads are then woven in to them.

Which brings us to “tweed”. Tweed was originally called tweel in Scots because it was woven in a twilled pattern. What that means is that instead of the weft threads going over one warp thread and then under the next, giving a smooth surface, it goes over two or three threads and under one or two, giving the fabric a pattern in the weave itself. It can be plain, or can have a herringbone or checked pattern by using two colors in the weft. If two or more colors of wool strands are twisted together before weaving, the cloth will have softly mixed colors called “heathering”.

The story goes that a merchant in London mis-read the handwriting from the weavers Wm. Watson & Sons, Dangerfield Mills. He took the word “tweel” for “tweed” thinking it was a trade-name for the River Tweed that runs through the area where the cloth was made. Once the advertising was done calling it “tweed”, it became known that way.

“Handwoven by the islanders at their homes in the Outer Hebrides, finished in the Outer Hebrides, and made from pure virgin wool dyed and spun in the Outer Hebrides.”

Harris Tweed Act of 1993

Harris Tweed is a very specific material that is woven in a specific way in a specific place. All Harris Tweed is woven on treadle looms in the homes of the weavers. Each specific pattern is done with hundreds of warp threads which have been tied by hand. The tweed is then sent to the mill where it is cleaned, dried, steamed, pressed and cut.

Typical ways to wear an Arasaide or Plaid

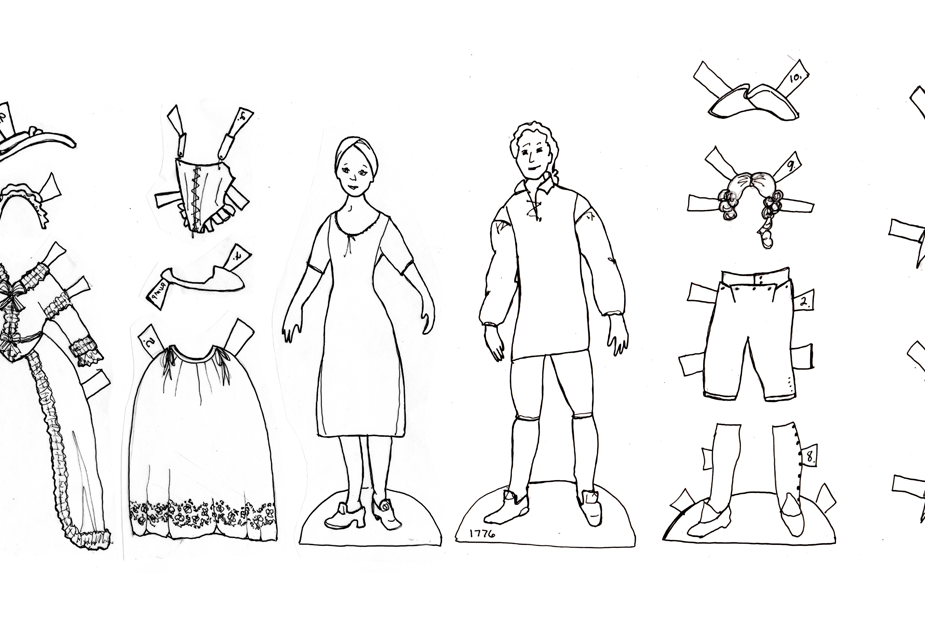

Susan is using the undergarments we created for her 1745 projects. She has 1780’s lavender stays that are well suited to this project as well.

To see the difference between the early 1740’s and later 1780’s stays, plus the general history of stays, please go to the following research pages:

Overview History of Stays and Corsets

For more information about fashion of this era in general including the use of undergarments , click here to go to an overview of Colonial Fashion and Lifestyle.

Click here to go to Susan’s 1785 Design Development with Extant photos (next)

Click here to go to Susan’s 1785 Main Page with the Finished Project

Click here to go to Susan’s 1785 Historical Context with Fashion History Page