Click here to go to Susan’s Design Development Page (next)

Click here to go to Susan’s Main Page with the Finished Project

Click here to go to Susan’s Historical Context Page

Fashion History for Two Times & Two Places

Women’s fashionable dress has seldom been designed for comfort

The main influences of fashion have been “style” and “coquetry” according to historians. The idea to dress for the weather or to be easy to get in or out of clothing is relatively new in the history of woman kind.

If you want to study fashion, take a look at the architecture of the day; e.g. the great houses of the 1870’s and ’80’s England had greenhouses attached to their backs – just like the bustles of the day. 20th century blousewaist hung over the waist like little balconies that were all the rage at the time.

Political and social situations such as feminism brought the copy of men’s fashion: boaters, caps, stiff high military collars, men’s shirts, and neck ties.

By the 16th century (1500’s) the only way these concepts were communicated was via dolls that were sent back and forth among aristocrats. By the 17th century the dolls were life sized, and used to see if garments fit. They were called “Pandoras”, sent out by French fashion houses to demonstrate clothing and hairstyle.

Not just fashion designers set the trends though, they just interpreted the moods and the marketability of society at the time. In reality, the concepts of beauty vs. ugliness were constantly changing as people and the world changed.

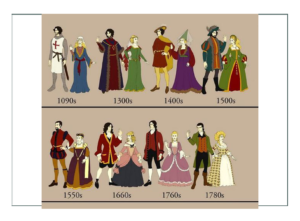

Out of Renaissance, & Into Georgian Fashion Eras

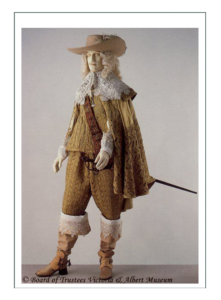

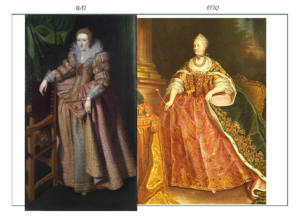

Formal Elizabethan (English) dress of the 16th century gradually became influenced by the French in the 17th. Stiffness and structures and complex and ornate stomachers slowly were cast aside in favor of softer fabrics and looser garments. The 17th century saw higher waistlines with more emphasis on the bust area, the “decolletage”. Lace and ribbons replaced stones and embroidery for the most part.

In the 2nd half of the century, fashionable dress became a dress with a bodice attached, petticoat, over gown and stays. The gown was no longer the only outer/over garment, it was the entire dress.

Stays of the 17th century were in plain view in front with lacing in the back. A woman’s diaphram was flattened and the bosom pushed up precariously high. Petticoats were cut the same as skirts, were trained, and worn a bit above the ankle. There was elaborate embroidery.

The word “gown” (“robe” en francaise) prior to the 1650’s meant the whole ensemble including undergarments and accessories. They had a stomacher and long pointy center with front tabs. Wealthy women wore jewels down the front.

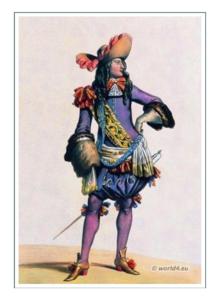

Louis XIII of France at the Front of the 17th Century

Louis XIII (13th) King of France in the 17th century (1600’s) had a fondness for Spanish fashion during his reign. When he married Spanish Princess, Anne of Austria, his passion for “things Spanish” spilled over into his directives towards French fashion design. Notable were the large fur-lined capes and crisp white collars of the doublets that originated in Southern Spain.

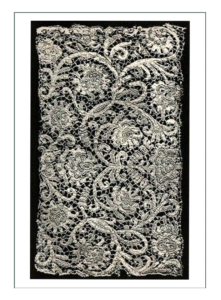

The soft falling ruff with its lace edges replaced previous decade’s of starched and wired lace around the neck for men and women.The “col rabatta” made of cotton lace, and the flat linen collar seen in Dutch paintings was popular around the world, led by the French. From these the 18th century fashions for both men and women evolved.

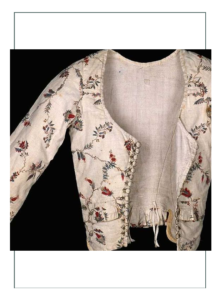

Women under Louis XIII in the early 1600’s discarded the large hoop (farthingale) worn previously. The “new” 17th century woman wore a bodice with a sharp center point that had puffed sleeves and slashed sleeves with lace. These were trimmed excessively and pulled back to cuffs.

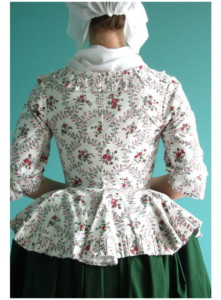

The skirt was open in front to show a richly ornamented under/inner petticoat which typically had rows of buttons, laces, and braids – sometimes all of them together. Some dresses (robes) had a peplum (wide ruffles over hip and rear end) over the skirt. These designs would appear in revised forms in the 18th century in the form of petticoats and jackets.

In the late 1600’s, puffs and drapes were pinned with knots of ribbons over the shoulders, another fashion that would repeat in the 1760’s. The main difference between the 17th and 18th mid-century fashions was that the early century had high waistbands with huge neck ruffs. The ruffs would be replaced later by ruffles, kilting, and fichus.

Louis XIV & Court Excess Through Transition

The eyes of fashion worldwide were on France during much of the 17th century under Louis XIII an d his heir Louis XIV. When Louis XIV (14th) took the crown, the manufacture of French lace was spurred on by his major marketing efforts and demand that all French people should buy exclusively from their own country. The King developed exclusive laces and needlepoints such as Alencan and Argentan lace which were named for the towns in which they were manufactured.

Extravagance in dress was encouraged by Louis XIV, called the “Grande Monarche” in order to stimulate the French economy. His mistress Mlle de la Valiere and wife Mme de Montespan slowed down the excesses somewhat by talking Louis into curbing back some of the pomp and splendor of Court dress.

There was a lull in change and evolution of women’s fashion from about 1700 to 1760 as far as innovations because of the two women tamping down the King’s crazy ideas. Designed stayed somewhat conservative and the same through those decades, with only subtle changes to undergarments, structures, and the way gowns were made or worn.

Louis won some battles though. Under his directives, women’s necklines went wider and more open with soft lace and muslin fabric around the bodice. Around the year 1700, the neck became squared and a paneled front was added. Sleeves were ornamented with “puffings” done in contrasting lace (to spur on the lace industry in France).

Just after 1700, sleeves started to be made of the same fabric as the bodice instead of contrast. They were made close fitting to the elbow instead of rounded, and then flared with ruffles, plaiting, lace, and ribbons, a look that would persist through the next century.

The new shorter sleeve demanded the arms be covered, so the fashion time around the year 1700 featured the innovation of over the elbow gloves. All of the above components would carry into the next century and the next French Monarchies.

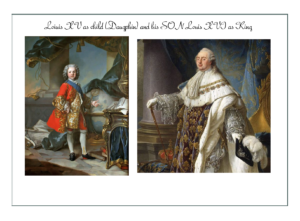

Louis XV & XVI – Wild & Crazy 18th Century

By the 1760’s, with the coronation of Marie Antoinette and her husband, King Louis XVI of France, the political turmoil of changes in power with the approaching French Revolution, world fashion following France’s lead changed to extremes and wild ideas. At the same time, conservative and stabile England sneaked ideas into French fashion as the balancing force for simple, clean, and functional garments.

The French still dominated European, and so Colonial fashion because Colonists followed Europe under Louis XV and XVI into the 18th Century. It was the Bourbon line that would lead the world until Napoleon’s reign of Terror started the French Revolution in about 1793 and ended with his crowing himself Emperor in 1804 which made a complete and shocking change of fashion that affected the whole world (discussed on other pages).

In the early 18th Century (1700’s), Courtiers were tired of the rules and restrictions of the prior Monarchies, so from the Duke D’Orlean’s Regency, until Marie Antoinette became the King’s Consort in 1770 at age 14 and established a new direction for style, there was a “wild abandon” of high fashion.

Many French fashion concepts of 1700-1760 actually came from their neighbor, England. The “Redingote” a double-breasted coat of heavy cloth for men with long skirts and big buttons evolved into various forms in the hands of the French for both men and women. This style would persist well into the 19th century.

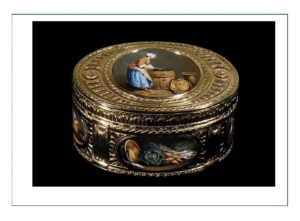

Ribbons, bows, and pocket watches which became the hallmark of fashion for Louis, were an English innovation. Men carried one all the time in a special pocket in their breeches, along with a box of snuff, even if they didn’t take the stuff.

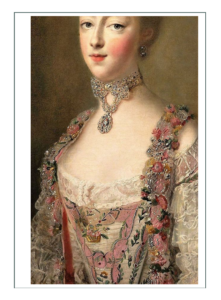

Madame Pompadour

For women around 1700 (late in the reign of Louis XIV while they were still somewhat conservative), the draping and lifting of the skirts entered the century with women somewhat confused as to what was fashionable. The “Panier”, a hoop invented in the prior century, was brought back and re-emerged in various forms as a definitive fashion statement for high fashion and Court Apparel.

Back draperies from the end of the 17th century disappeared, leaving the back over the rear end flat, so that the skirt billowed to the sides. As the 1760’s approached, the sideways design got bigger and more dominant. Lace, ruffles, bows, and ribbon were required to be fashionable.

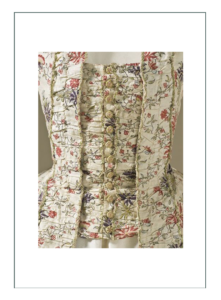

At last under Louis’ “advisor” (carefully trained and groomed all her life to be a King’s mistress), Mme Pompadour, the fashion of the day was pinned down with exacting rules. The square neck was established, and the method of construction in the late 1750’s which would persist for at least 30 years to follow.

By the 1750’s under Mme Pompadour, sleeves became closely fitted and were made of the same fabric as the bodice. The sleeve matched from shoulder to elbow, where it had a ruffle, usually two layers offset, of lae attached. Skirts were open in front, putting elaborate matching or coordinating “outer petticoats” on display.

Influence of Non-Royals – Watteau

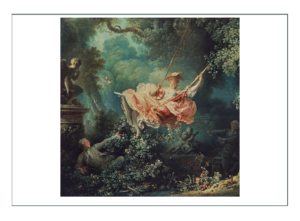

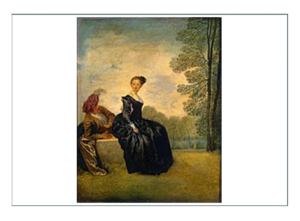

Watteau painted portraits of every day people in France as well as Royals. By 1712 he was wildly known and popular for his placement of real or imaginary people in idyllic settings that told a story; many times with subtle humor or jabs. His art introduced a style to the people apart from rigid Court dictates towards the baroque ideals of informal, natural, and intimate situations. People, especially the French, wanted less formality and more naturalness in their daily fashion. They took the concept from Watteau’s art.

The “Watteau”, a method of draping and pleating eventually became the name for a type of gown which hung from the shoulders in the back, and was caught up in huge pleats which also were named “Watteaus”.

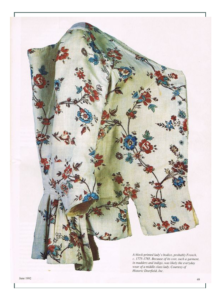

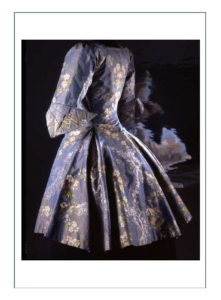

The heavy rich fabrics and ornament from the late 17th century did carry over well into the 1770’s, but in the 1740’s and 1750’s, color and fabric changed from the heavy drapery like silks and brocades with jewels and gems as ornament, into buoyant silks, with delicate patterns such as florals and stripes, and little motifs. Color was lighter in hue and saturation, and there was a “tenderness” in the look of women’s clothing after the “heavy darkness” of the preceding eras.

Mme Pompadour sponsored the arts and artists such as Watteau, and introduced the new concepts to the King who then directed the rest of the world to follow the style.

Marie Antoinette Makes her Mark – Up

When Marie Antionette became Queen of France in the early 1770’s, skirts were already elaborated festooned. In the 1760’s, hair was simple, but by the time Marie got hold of fashion, hair had become the notable and elaborate feature of a woman’s ensemble. Under her example, hats became either huge or embarrasingly tiny on top of elaborate coiffures that rose up to 36″ in height.

Paniers became more than 8′ across, and women wore fur-covered “mantles” (capelets). The English had by 1787 designed a long cloth coat with double rows of buttons in front and shoulder capes which the French copied to keep these rather exposed women warm. The French also copied the English and added a HUGE fichu, or scarf that covered all the bare skin of the bodice. This focus on the breast and addition of large amounts of fabric just made the breast all the more prominant, a feature that continued to exaggerate until the end of the century.

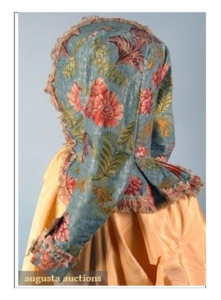

Accessories included long handled parasols and large hand muffs as the century progressed too. The new lightweight silks and eventually cottons were chilly in European climates, and much of the American Colonies, so new outer garments were invented and made of warm velvet, satin, taffeta – always with lovely florals and motifs. Printed cambric fabrics became in high demand in the 1760’s when a Frenchman, Oberkamft, built a textile printing factory just outside the French palace at Versailles.

Designs were often painted by hand or embroidered onto fabric and especially silks. Colors had names like “stifled sigh” or “the lovely shepherdess”.

Click here to go to the Colonial Fashion Specific Page

European, Colonial, Irish-Scots

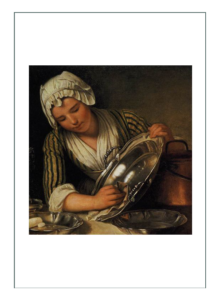

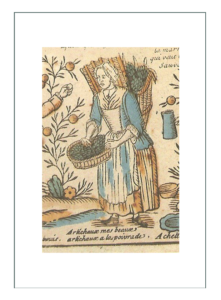

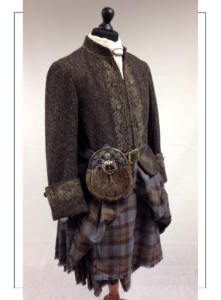

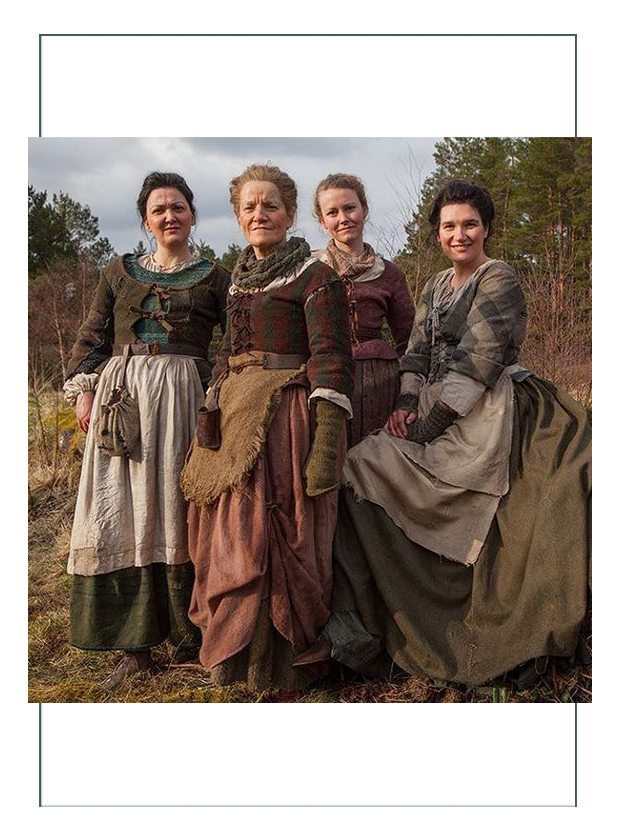

The development of these is discussed in the fashion eras above. Here are examples of the many types worn from 1740-1780; common to all locations being investigated. Notably these were worn in the Colonies BY the locals and immigrants from both Europe and Scotland.

Click here to go to the Celtic/Highlander Fashion Specific Page

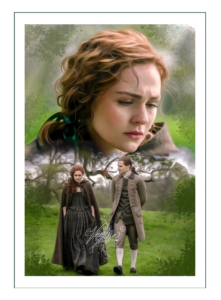

The fashions of “Outlander”

Educating the Modern World the Fun Way

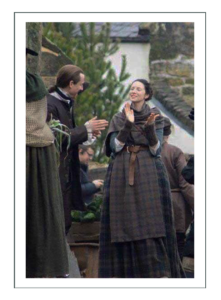

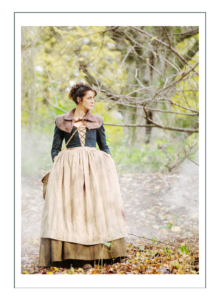

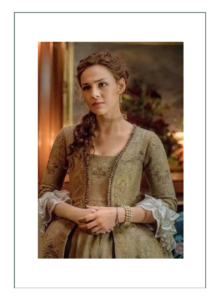

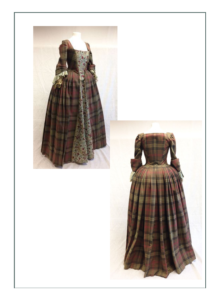

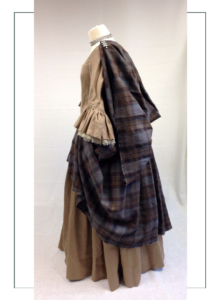

The outlander story was outlined in the history section. These images are presented as examples of the finest modern accurate reproductions today. What we can summarize from these is the consistency of the correct undergarments for each decade (1740’s-70’s) plus the translation of the original Scots – who had a blend of European and Highland fashion.

The Colonists also had a blend of European fashion.. plus whichever country they originated. The Colonial – or “New America” fashion was in fact a merging and blending of all things of fashion. Americans, however, with their “function first” attitude and limited access to goods being yet somewhat remote to world trade, would have leaned towards the lower or working class interpretations of fashion – EXACTLY – as the Highland Scots would have done as they lived next door to England and were allied with France.

We summarize the selection of garments for this interpretation can be pretty much “anything goes” in selecting from either era, and either country – or a blend of it all. The only restriction is that this must be a lower or working class for a healer. Just like Claire:

1745 Scotland

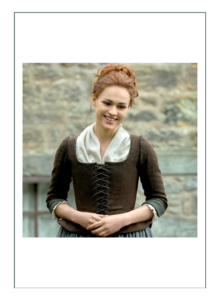

The first image is the wedding gown with the low rounded bodice of the 1740’s with the lace sleeves in contrast. This is just for pleasure; we have no intent on building anything like this (yet). We do note looking at the 1740’s Scottish photos a theme of indigo blue and the natural browns of the typical Scottish weave. Even her wedding gown is really a natural dye color, and probably linen – of a certain type that has a sort of irridescence.

The plaid is not the Fraser plaid, and it is not the Mackenzie, although the sales sites say it’s an “Outlander Mackenzie” (It’s also not the author’s Macduff). It’s pretty though.

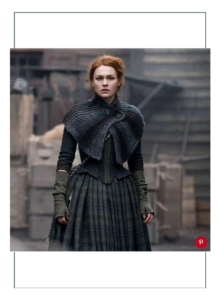

It appears this is costuming to keep a color scheme per character. Claire’s Scottish journeys include entirely wools; worsted wools to be exact. The cast each has a monochromatic color scheme in worsted wool too.

177o Scotland

Claire comes back wearing her 1970’s synthetic raincoat (presumably nylon) and a zipper with synthetic “stays” made from an old slip and bra. Her first ensembles look to be cotton.

Brianna joins them with what are supposedly Claire’s handmedowns at first, but quickly switches to her own color scheme in the red/orange range. Monochromatic and earth tones with Scottish wovens again – UNTIL – she stays with her great aunt. Then they do the real 1770’s thing; dress her in India block printed cotton chintz with linen petticoats. Right on, costumers!

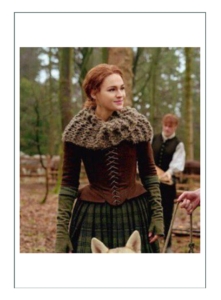

1770 Colonies

By the time they reunite in the Colonies, all characters have their color schemes down which now combine with the furs and leathers typical of frontiersmen of the time. They’re obviously in a southern climate because it never gets much colder than the summers in the Highlands. Gauntlets and waistcoats are the name of the game; hubba hubba. There’s nothing like a handsome backwoodsman wearing his waistcoat to cut wood.

Claire’s Arisaid

Whose plaid is this? The “Outlander plaid” we presume. Since the Highlander’s dress was outlawed after the rebellion until 1800 (1805), we can only assume these are pre-Rebellion ensembles from the first show. The design again does indicate the 1740’s – late into the 1760’s. Claire sticks to her color scheme!

center pinned closure

Click here to go to Susan’s Design Development Page (next)

Click here to go to Susan’s Main Page with the Finished Project

Click here to go to Susan’s Historical Context Page

Click here to go back to the top of this Page

Click here to go to the Colonial Fashion Specific Page

Click here to go to the Celtic/Highlander Fashion Specific Page