Scroll down to see the finished project

Click here to go to the Historical Context page

Click here to go to the Fashion History page

Click here to go to the Design Development page

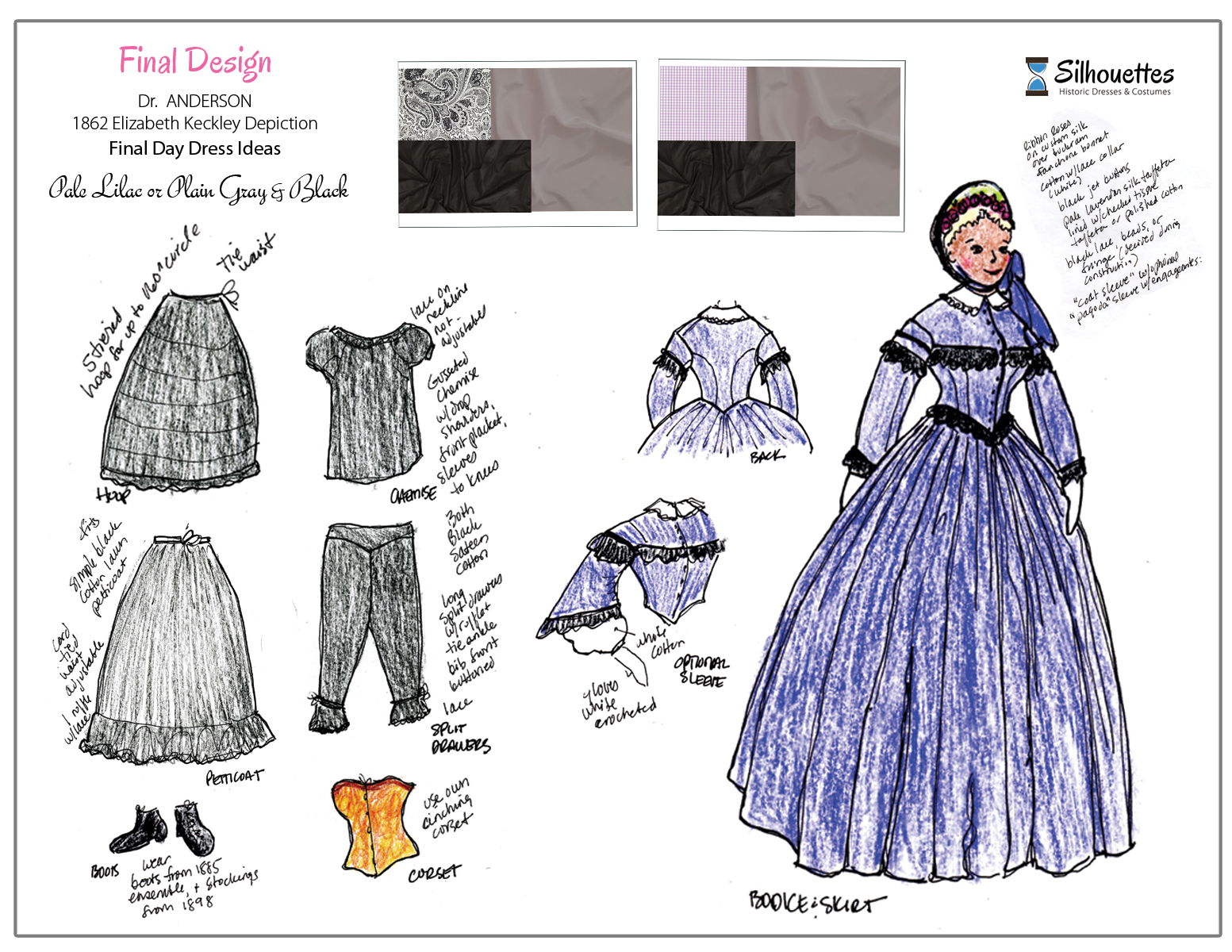

Dr. Anderson, 1862 Elizabeth Keckley “Mrs. Lincon’s Dressmaker”

Real or Fictional?

This depiction started as a study of key figures before and during America’s War Between The States (aka “Civil War”). Dr. Anderson intends to wear her ensemble each year in teaching this section to her elementary school students, along with activities and “hands on” procedures.

Her first thought was to depict a real and know woman of the day such as those she would be teaching specific lessons on: Mary Todd Lincoln, Harriet Tubman, Elizabeth Stanton, and Susan Anthony for example. She also wanted to do something grand and sweeping – different than the other ensembles we had built for her – that would catch the attention of everyone right away.

This would be the best lesson yet for using her costume to teach. The problem was, of historical characters, really only Mrs. Lincoln focused on the highest fashion of the day. In a war torn country, it was difficult for most women to obtain or afford fancy goods.

At A CrossRoads of Sorts

That left us with finding a different notable character, or developing the “typical woman of the day” based on research. In developing the Historical Context for the era, we found real diaries and a summary of their content of women who lived “at the crossroads”, or in a type of “middle ground” between the north and the south. Their lives were full of issues regarding the war, and they were of different sympathies, yet they had very much in common as we discuss on that page.

We recommended to Dr. Anderson that we focus on the year of 1862 because it has very specific and easy to recognize fashion characteristics and construction methods that are easy to teach. It’s not the largest crinoline era, but it is the one most noted in documents and photos, because the year was early in the war and women had hope the war would soon be over. Most had not lost their homes or plantations, and leisure might have been more abundant for some.

Of course we are referring to middle and upper classes, which were the strength of the American economy at the time, and must make a conscious decision to not depict slaves, low or working class, rural, or pioneer women.

In the decision to create an ensemble of formal wear, or a ball gown, the depiction needs to be of a high enough class, status, and wealth to be able to afford and have time to wear evening wear.

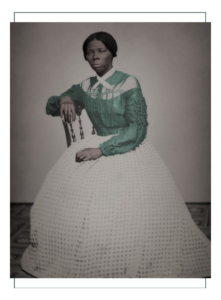

Below: Rural and Settler clothing (1), while the same style, would be depicted much differently than a duchess (center), or Louisa May Alcott of the middle class (3)

A Subjective Decision

We recommended to the good doctor then, that she base her character on a combination of real women of the day; those we describe on the history pages, and to use that character to describe her position RELATIVE to the characters she is teaching about. For example, to describe Harriet Tubman from the perspective of a Northern Sympathizer from Ohio who has brothers in the Union army, would be quite different than from that of a Southern Sympathizer from a plantation in the Carolinas with brothers in the Confederate army.

One she chooses a position from which to make observations, she can teach from that position. As far as the ensemble we build her, it won’t really matter unless she goes to extremes. For a woman to dress grandly for a ball, she must be of upper middle to upper class, and have a secure home environment with sources of income and access to goods.

We Begin with the Best

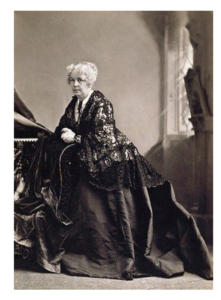

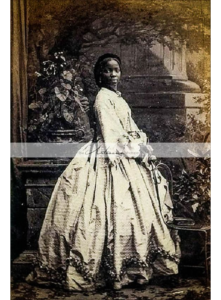

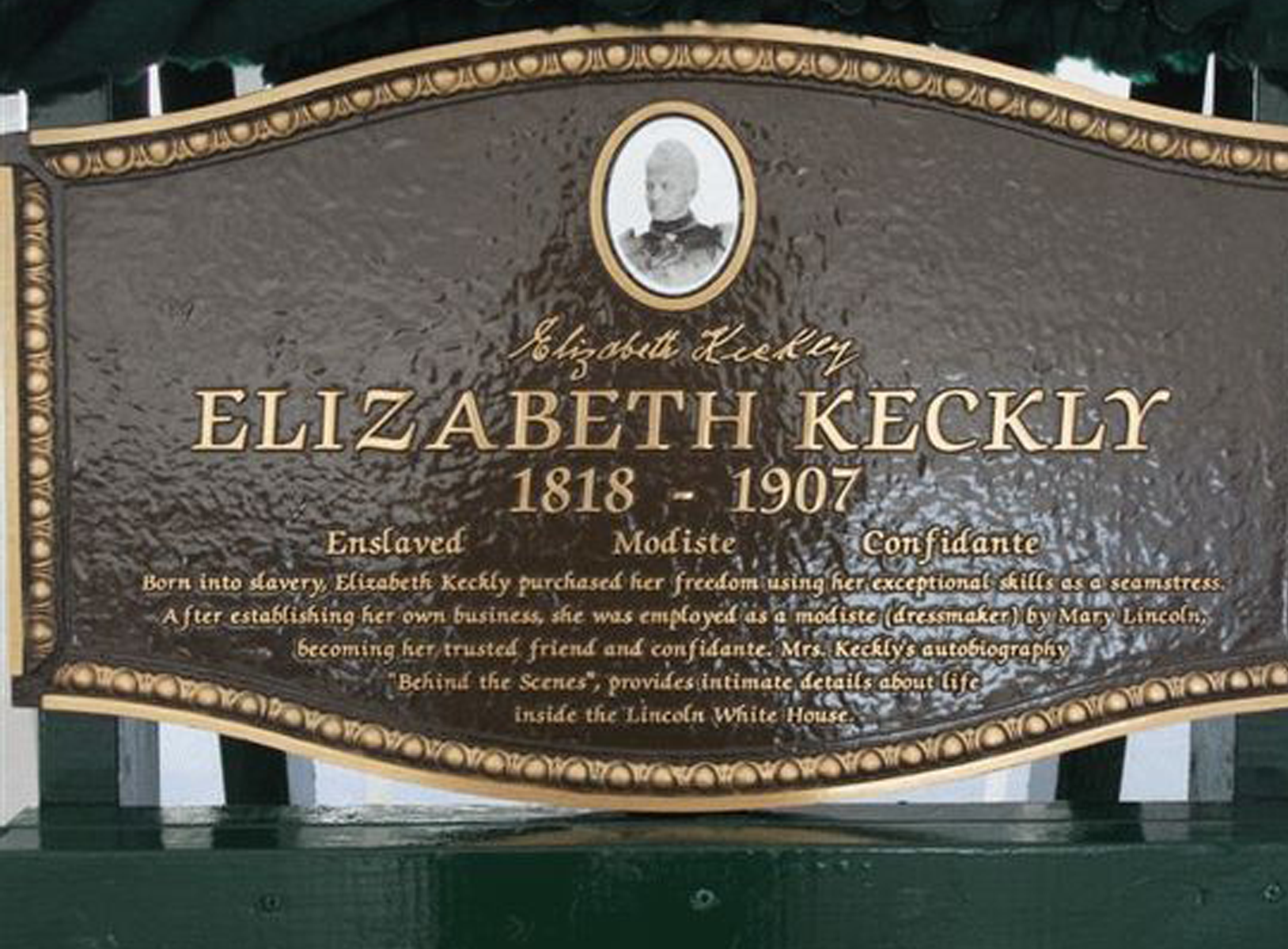

Dr. Anderson, after studying the diaries, real people, extant garments, and the realities of fabric and notion availability and cost for the project, has decided on a depiction of “Mrs. Lincoln’s Dressmaker”, Elizabeth Keckley. Yvonne wanted a real woman of the day for a real depiction, and needed an African-American depiction. Mrs. Keckley will be PERFECT in that she was at a Crossroads of sorts as she lived between the world of the freed slave and the upper crust of Washington society. She had access to the White House, secrets, as well as “on the streets” information.

Her story tells of her journey from slave to entrepreneur, from South to North, and it involves all the issues and concepts of the day from the perspective of an insider who is really an outsider. It tells the tale of love and loss; rise and fall. The best part about her story is we have a few photographs, documents, and enough fictional support to make a good estimate as to how she would have dressed and behaved.

It also resolves the issue of how Dr. Anderson will modestly cover her neckline in a time where evening wear revealed all. It makes the decision to make a high end day dress, and that has to be silk taffeta with tiny checks, stripes, or solid color. Moreover, with Mrs. Keckley being heralded as the most talented seamstress of the day, it allows us to show off our fancy work and unique design. For this we get to study Mrs. Lincoln’s dresses, since most were Mrs. Keckley’s original designs from which to draw inspiration for the type of ensemble Mrs. Keckley would have made for herself!

In Brief

(See the Fashion History Page for analysis of Mrs. Keckley’s designs for Mrs. Lincoln)

Elizabeth Keckley was Mrs. Lincoln’s dressmaker. We researched Mrs. Lincoln, Mrs. Keckley, and the era in general from all possible resources, but even the fictional stories of her seem to almost word for word rely on Mrs. Keckley’s autobiography.

As we are fans of first hand resources, the following brief chronology is based on “Behind the Scenes” or “Thirty Years a Slave and Four Years in the White House” written by Mrs. Keckley herself and published in 1868.

The Virginia Museum of History and Culture Website summarizes her life:

“Born a slave in Dinwiddie County, Virginia, Elizabeth Hobbs Keckley (1818-1907) purchased her freedom in 1855 and supported herself as a seamstress, first in St. Louis, and then in Washington, D.C. Her skills brought her to the attention of Mary Todd Lincoln, who hired Keckley in 1861. Keckley became Mary Lincoln’s favorite dressmaker and later her personal companion, confidante, and traveling companion. It was a remarkable friendship between two very different women, but it ended with the publication of Keckley’s memoirs in 1868.

During her White House years, Keckley organized relief and educational programs for emancipated slaves with the help of Frederick Douglass. Her only son enlisted in the U.S. Army and was killed at the battle of Wilson’s Creek, Missouri.

Keckley published her autobiography three years after Lincoln’s assassination. Although she apparently thought her revealing book would help restore her former employer’s reputation, it had the opposite effect, and Mrs. Lincoln felt betrayed by the woman she described as “my best living friend”. The two women never spoke again, and Keckley’s successful dressmaking business declined. She died in Washington in 1907 at the National Home for Destitute Colored Women and Children.”

Early Years

Elizabeth Hobbs was born a slave in Dinwiddie County, Virginia, just south of Petersburg (author’s note: Suzi, Silhouette’s proprietor’s, proven ancestor owned the plantation next door and the masters were friendly rivals!). Her mother Agnes was a house slave, likely of mixed race, owned by planter Armistead Burwell and his wife Mary. Elizabeth’s father was Mr. Burwell, and it was believed through Agnes, Elizabeth had additional caucasian heritage.

Agnes married George Hobbs, and both were literate and lived as a family until Hobbs was forced to move away with his owners and were never reunited, although they corresponded through their lives. Keckley remembers the hopeful letters and love of that time. She lived with her mother and began official slave duties at 4 years old. Left to take care of the Burwell’s new baby, she tipped the cradle over, spilling out the baby, and then tried to scoop him up with the fire shovel. Finding her thus, Mrs. Burwell gave Elizabeth her first beating.

At age 14, Elizabeth was “loaned” to the Burwell’s son, Robert, in Chesterfield County, near Petersburg. Robert’s new bride Margaret disliked Elizabeth immediately, perhaps because of Elizabeth’s clear caucasian ancestry, or perhaps because Elizabeth resembled Robert (being half brother and sister it was determined later). Margaret made life difficult, and Elizabeth moved with the family to North Carolina where Robert became a minister and operated the Burwell School for Girls from his house 1827-1857.

When Elizabeth was 18, Robert enlisted his friend William Bingham to help subdue Elizabeth’s “stubborn pride”. At Bingham’s home, Elizabeth was forced to strip and was beaten on 2 occasions. On the 3rd, she states he had a change of heart, apologized, and promised not to do it again.

Another prominent caucasian man of Hillsborough, Alexander Kirkland, forced a sexual relationship on Elizabeth for four years which she barely touches upon in her biography, but described as “suffering and deep mortification”. In 1839 she gave birth to Kirkland’s son, and named him George after her stepfather (Hobbs). She and George were returned to Virginia where her original master “gave” her to another family member, daughter Ann Burwell Garland. Ann was also a half-sister to Elizabeth.

Freedom!

The Garland family moved to St. Louis, Missouri, taking Agnes “Aggy” and her daughter Elizabeth with baby George with them. Times were hard, so the Garlands “hired out” Elizabeth to do sewing for friends and neighbors. 12 years as a seamstress in St. Louis, working for high class women earned her a reputation among caucasians and the free blacks that lived there.

Elizabeth met James Keckley in St. Louis, who falsely claimed to be a freed man and a sober one. Elizabeth indicated “gently” that he was a drunk and a liar. She wanted to wait to marry until she could earn enough money to buy her freedom. The Garlands set a price of $1200 for her to buy herself and George out of slavery.

That was a huge amount because most of her money earned was given to the Garland family, so Mrs. Garland suggested Elizabeth appeal to her patrons and customers for a loan. She married James after two years of persuasion, and almost immediately left him due to his drinking. She earned her freedom in 1855, but stayed in St. Louis long enough to pay back her lenders, because as a free woman, she could keep all her earnings.

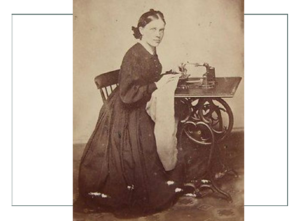

In early 1860, she and George moved to Baltimore Maryland with the intent to run sewing classes for “colored women” to teach her system of cutting and fitting dresses. At this time she was called a “mantua-maker”, an 18th century term refering to the fitting of bodices for the current fashion.

Maryland was passing restrictive laws against freed blacks, so it was not profitable, and she moved to Washington to find better prospects and to start a sewing business.

In Capital City

In Washington City, Maryland in the early 1860’s, a freed black had to buy a license to reside inside the city boundaries. Since Keckley had very little money, a customer, Miss Ringold, was able to obtain a license for Elizabeth using connections to Mayor Berret for free. As she built clientele, her customers became higher and higher in social and political status, giving Keckley continuing growth in notoriety by word-of-mouth recommendations.

Some of her customers included: Mary Jane Welles, wife of the Secretary of the Navy, Margaret Canera, wife of the Secretary of War, and Adele Douglas, wife of Senator Douglas of Illinois and the “Lincoln-Douglas Debates” fame.

When Keckley became Varina Davis’ personal seamstress, Keckley’s fame and orders grew to the point she hired young black women including a receptionist. Mrs. Davis would move to the south, where her husband would become “President” of the Confederates. Through connection with Mrs. Davis, however, Elizabeth traded construction of a dress for an introduction to Mary Lincoln in the White House.

That introduction was confused, as Elizabeth was called, yet not exactly called, to the White House, and so did not go until the following morning to meet with Mrs. Lincoln at a nearby inn instead, where Mrs. Lincoln was preparing for the inaugeration. There were many seamstresses on hand for interview, but after a short conversation in which Mrs. Lincoln was very aggravated that Elizabeth had not come earlier, satisfied the First Lady, and Elizabeth was given some alteration projects to test her skills.

Mrs. Lincoln chose Elizabeth not only to design and construct her many ideas and many gowns, but also to dress her and prepare her hair, undergarments, and help in general with preparations for events. Elizabeth was called a “modiste” in this role.

During the entire Lincoln administration, Elizabeth was solely responsible for the entire event wardrobe of the First Lady. The 1862 portraits of Mrs. Lincoln were taken in Keckley gowns:

Contraband Relief Association

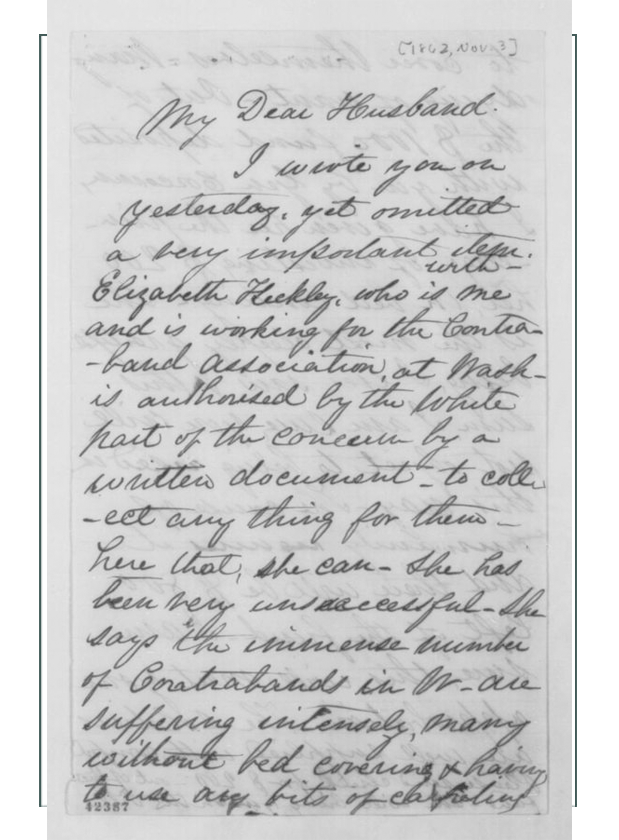

Living in Washington City during a war, she saw the plight of freed slaves and soldiers alike, and used her influence to establish the Contraband Relief Association in August of 1862. She used donations from the Lincoln’s, and wealthy blacks and whites to provide food, shelter, clothing, and emotional support to recently freed slaves and sick or wounded soldiers. The name was changed to the “Ladies’ Freedmen and Soldier’s Relief Association” to reflect its expanded mission which was to help people not only in the city, but in the surrounding region.

The organization did not last beyond the war, but the organization of the black community through networking and support, along with visibility of the conditions of the poor, had others follow in her plan. Churches in particular came together interdenominationally which had not been done before, and prominent black features rose to the cause.

Relationship with Mrs. Lincoln

Besides making her clothing and dressing her, Elizabeth became a close personal friend and confidante to the First Lady at a time society was very harsh on Mrs. Lincoln. Elizabeth observed the emotional struggles of Mrs. Lincoln who wanted to have input in her husband’s decisions, and got to be part of the family at private times and in private quarters.

When the darling youngest son of the Lincolns, William “Willie” died suddenly, Elizabeth was one of few who could console the First Lady who went into deep and hysterical mourning according to her biography. Keckley’s own son George was killed in action early in the war. Against her wishes, George who was light skinned and could pass for white, had enlisted in the Union Army and was fighting in an early skirmish in Missouri when he died.

Keckley also comforted Mrs. Lincoln at the assassination of Mr. Lincoln. Elizabeth did not know of the death until the morning after, and by the time she got to the White House, Mrs. Lincoln was nearly out of her mind with grief (again). Mary gave Elizabeth the gloves and cloak Abraham had been wearing at the time, as well as his brush that Elizabeth had sometimes used to smooth his unruly hair.

When Mrs. Lincoln was forced to leave the White House immediately, Elizabeth had to stay in Washington for her business. It was a time of emotional letters between the two of them; letters later published in Elizabeth’s biography.

Fading From History

Both Elizabeth and Mrs. Lincoln gradually faded from the spotlight of history after Mr. Lincoln’s death. Elizabeth donated her memorabilia to Wilberforce College to help raise funds to rebuild after a fire in 1865. Mrs. Lincoln was angry at her giving away the personal and private gifts. Elizabeth got them back.

In 1868, when the autobiography was published, Mrs. Lincoln was in what became known as “the old clothes scandal”, in which she was trying to sell her many wonderful items to support herself and Tad who were now living in Chicago without any means of support.

The public’s response was to once again criticize Mrs. Lincoln for her shameful behavior in their eyes, and the actions of the auctioneers and others led to further condemnation. Mrs. Keckley wrote the memoirs in attempt to raise Mrs. Lincoln’s status, or to give some understanding to the public of the situation.

It served only to completely destroy the relationship between Mrs. Keckley and Mrs. Lincoln. Mrs. Keckley suffered in business from her association with the former First Lady, and eventually became desititute. She tried to earn money by teaching young girls her techniques, but most of her white clientele shut her off entirely. she eventually sold the 26 articles that were given to her by Mrs. Lincoln for $250.

In 1892, she was offered a faculty position at Wilberforce University as head of the Department of Sewing and Domestic Science Arts and moved to Ohio. There she organized a dress exhibit at the Chicago World’s Fair.

Presumeably due to health reasons, she retired in the late 1890’s to the National HOme in Washington, which had been founded using funds she had raised for the Contraband Association. She led a quiet and secluded life out of the public’s yes, and suffered from headaches and crying spells, much like Mrs. Lincoln had.

Elizabeth hung Mrs. Lincoln’s portrait on her wall, and told friends she had reconciled with her friend after Mary had contacted her. She died in 1907 while a resident of the “Home”, and was buried in Columbian Harmony Cemetery in Washington, D.C., but her remains were transferred in 1960 to National Harmony Memorial Park in Landover, Maryland when Columbian Harmony closed for a city development.

There is a plaque across the street from the site of the former home.

Click here to go to the 1862 Historical Context Page (next)

Click here to go to the 1862 Fashion History Page

Click here to go to the 1862 Design Development Page

Continue below to see the finished project

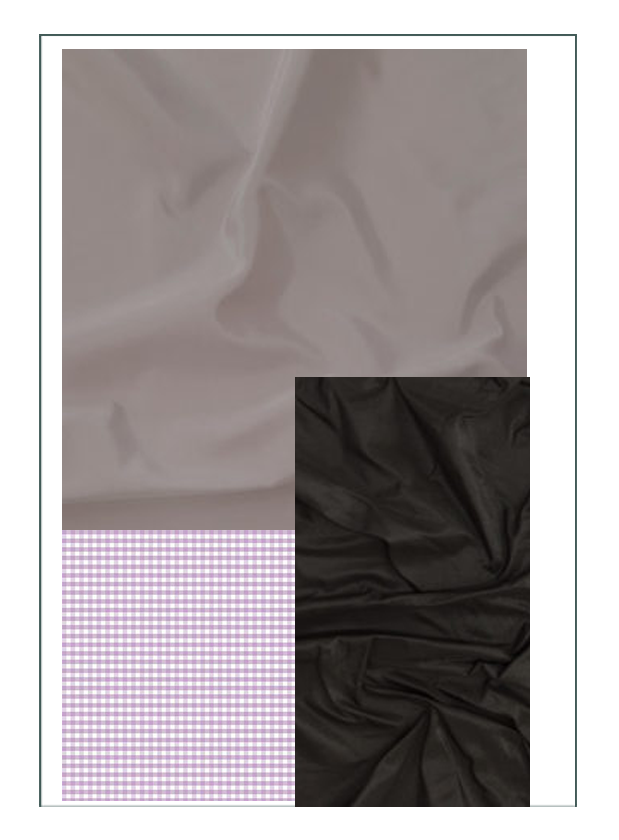

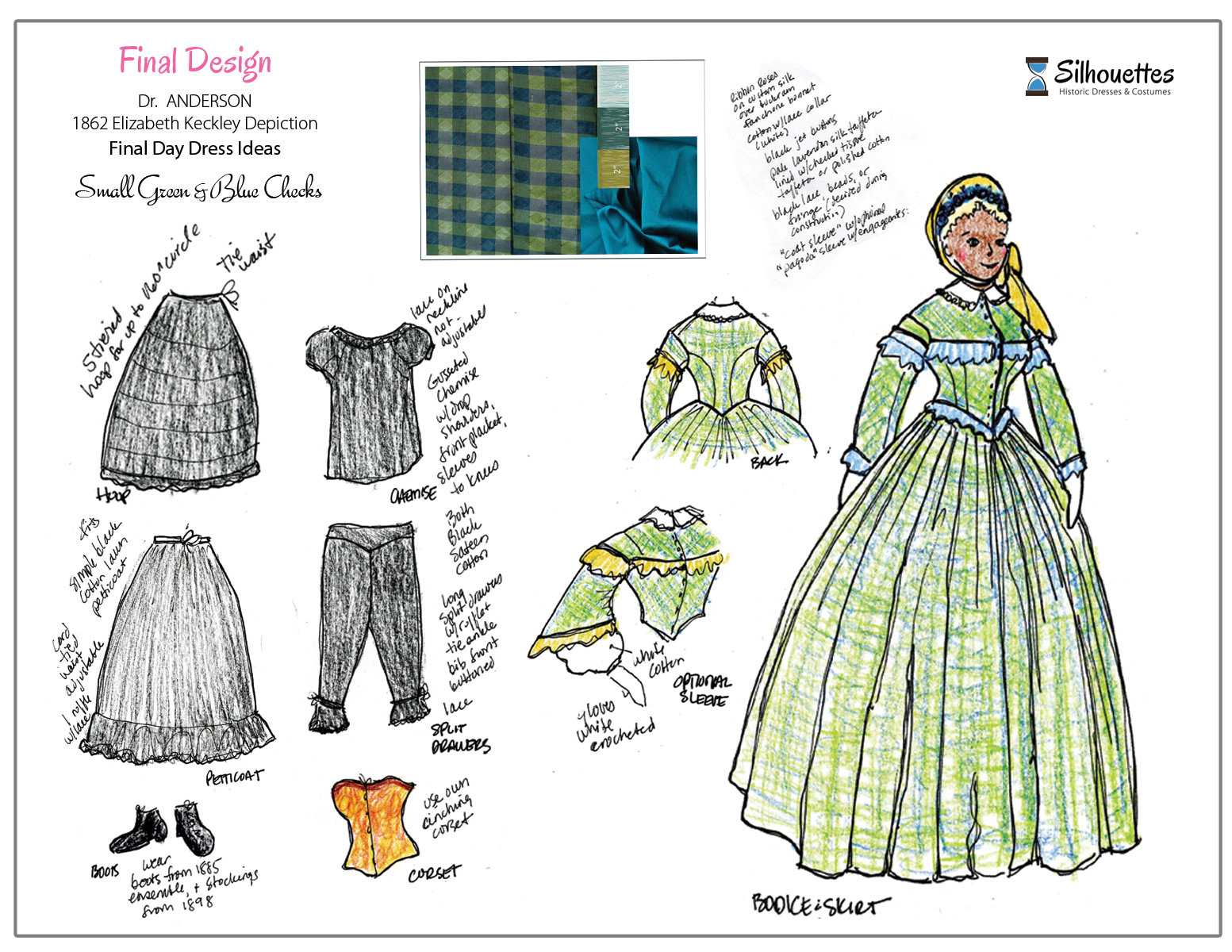

Design Sketches & Fabrics

The final project will include:

- Bodice

- Skirt

- Fanchon Bonnet

- Hoop

- Petticoat

- Chemise

- Split Drawers

- Crocheted Gloves

- White Collar

(She already has corset, stockings, boots/shoes. Engageantes possibly if option of pagoda sleeves selected)

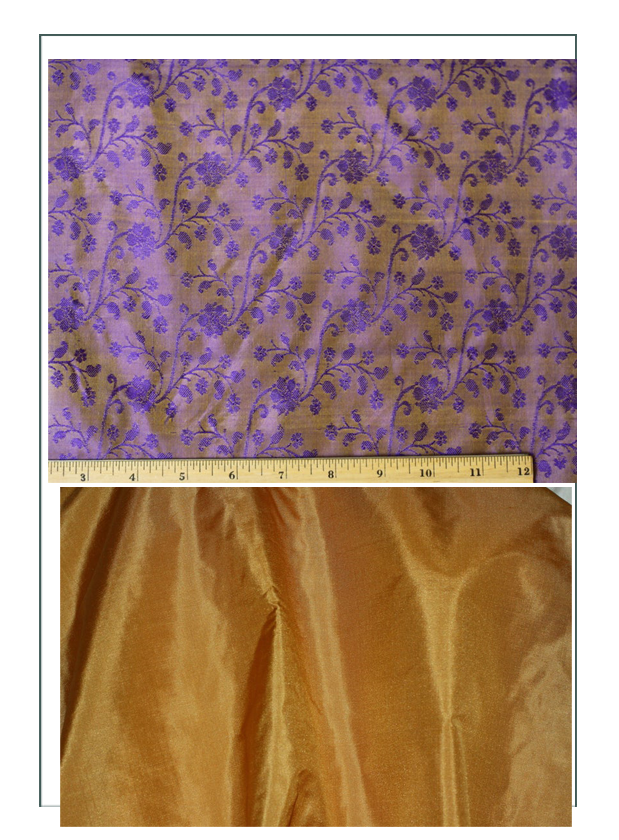

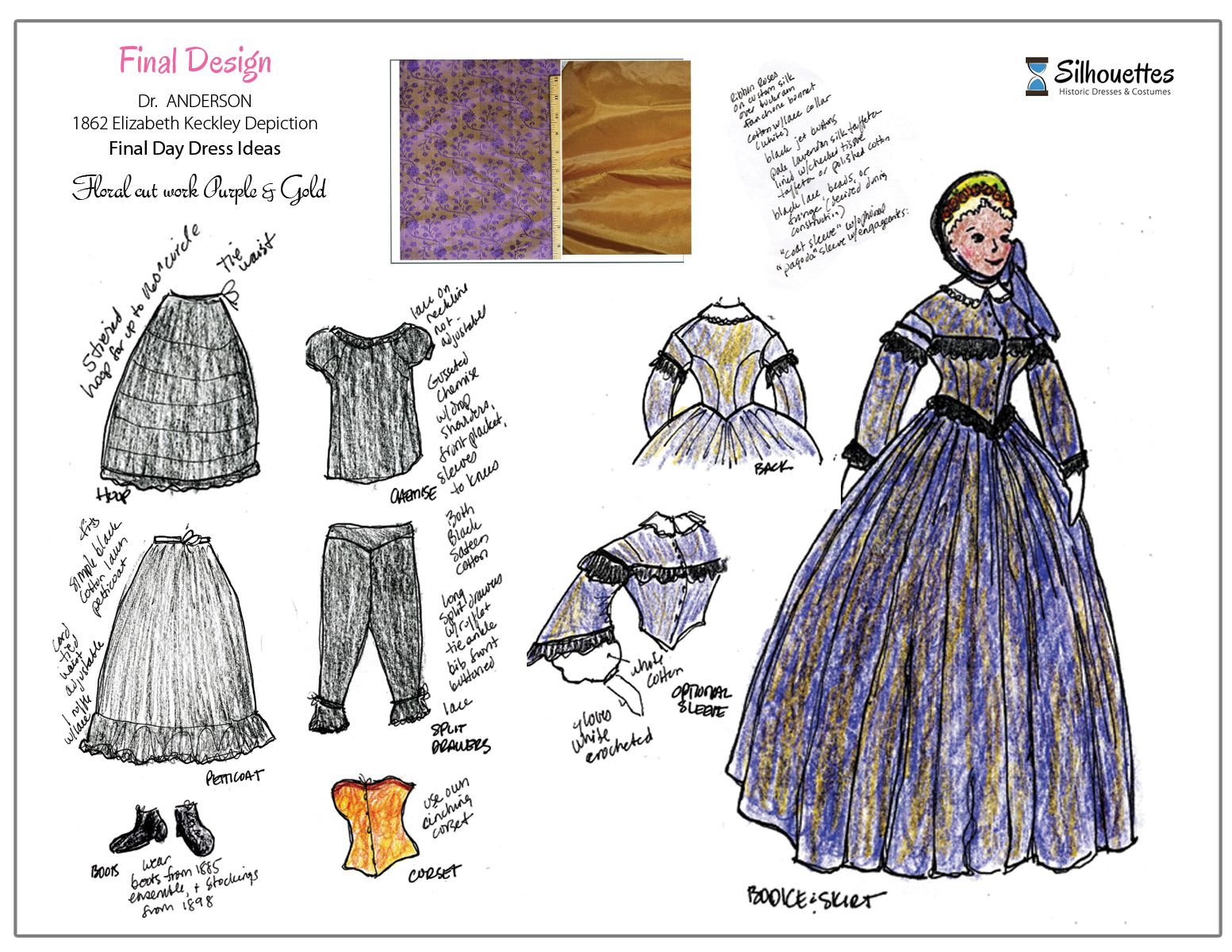

Selected Design

A subjective decision, it was up to Dr. Anderson to decide what she would like to invest in…

The winner is!

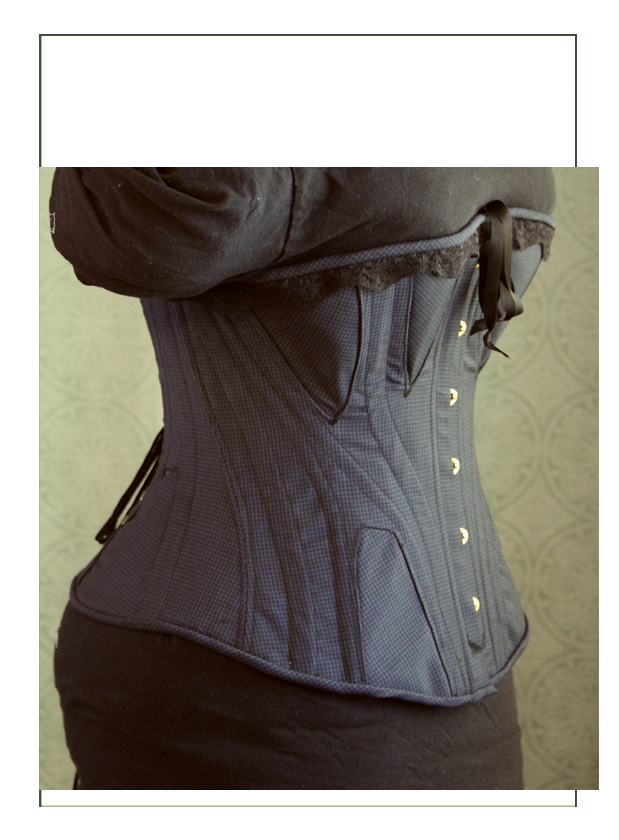

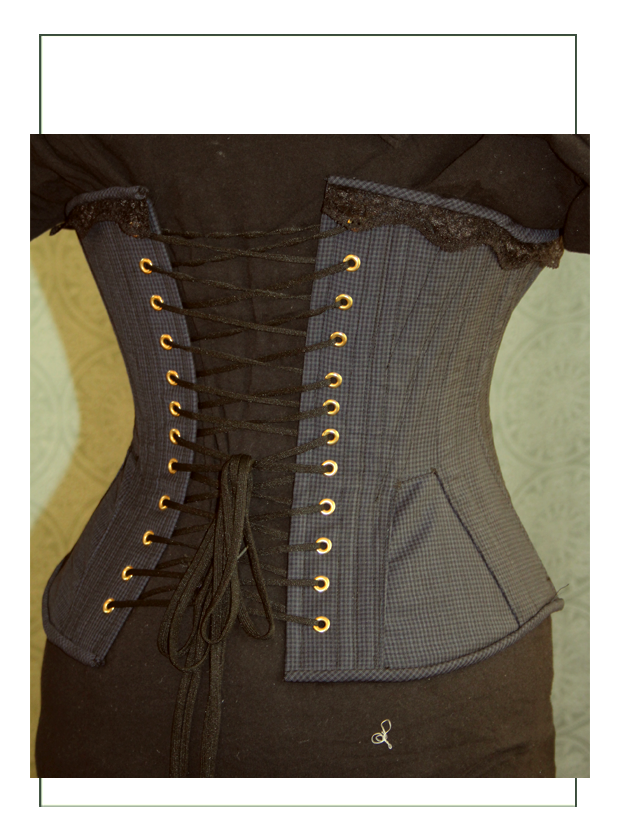

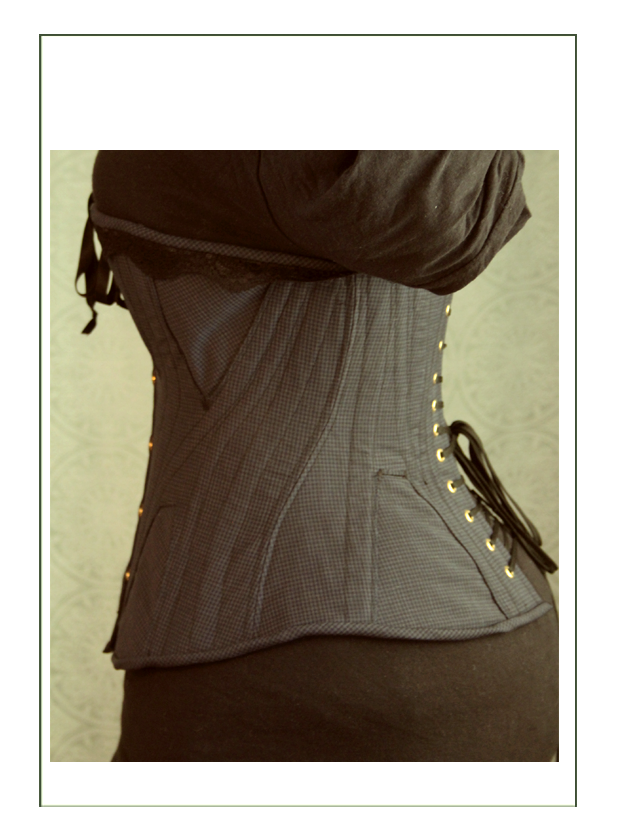

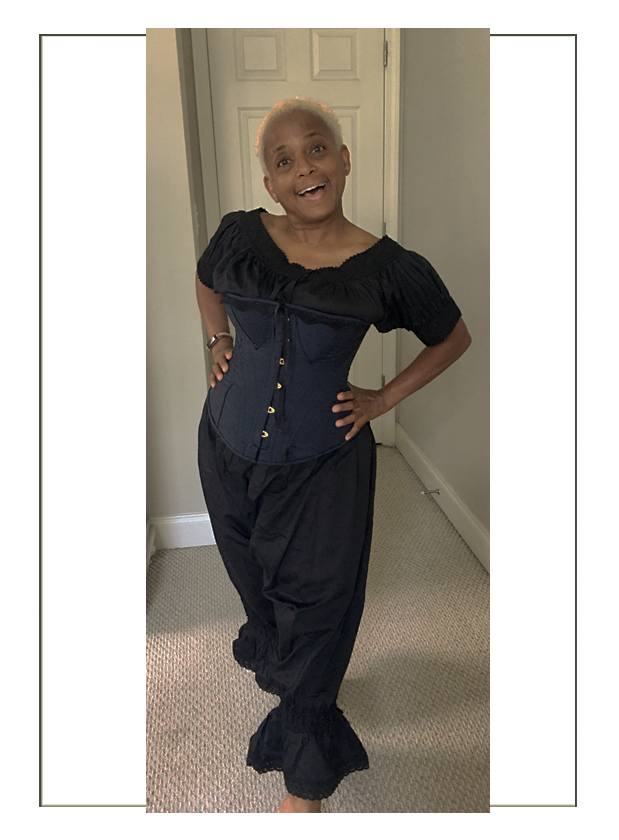

Temporary Corset

Because Dr. Anderson has her own corset and will wear that for the project, we needed to make one for draping on the dummy. This we will cinch 3″ tighter than usual, and add more lift, as the goal is the tiny waist of the 1860’s.

This is a wool and silk blend “pique” (woven as checks) fabric with a synthetic lace and straight metal busk. It is made exactly as the one she has, though a “smidge” lighter in weight due to selected fabrics. It is fully lined and has inner support tape plus the specially placed grommets for tight waist cinching.

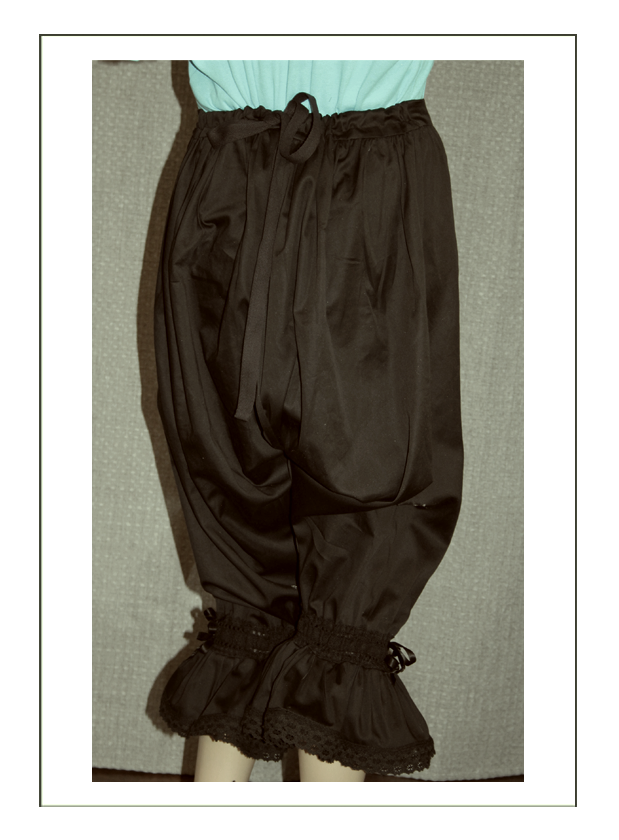

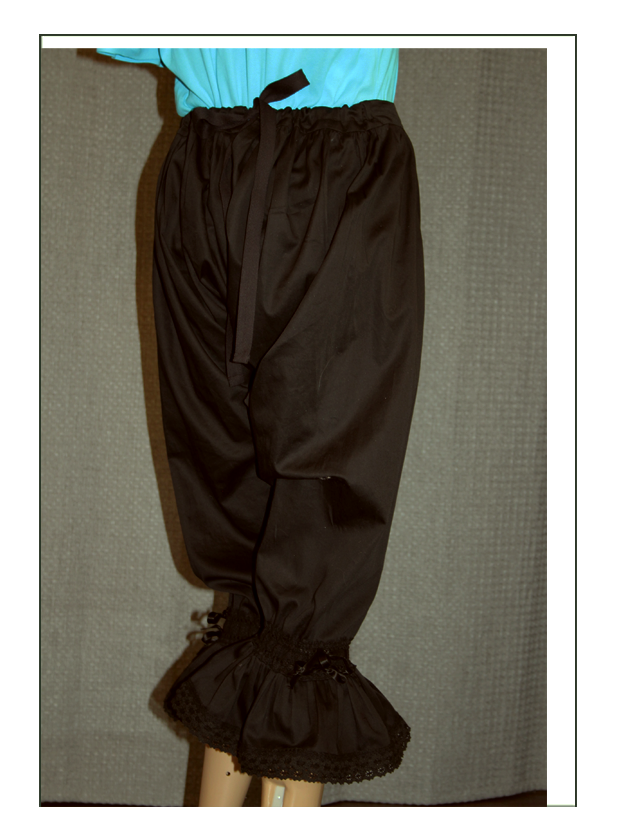

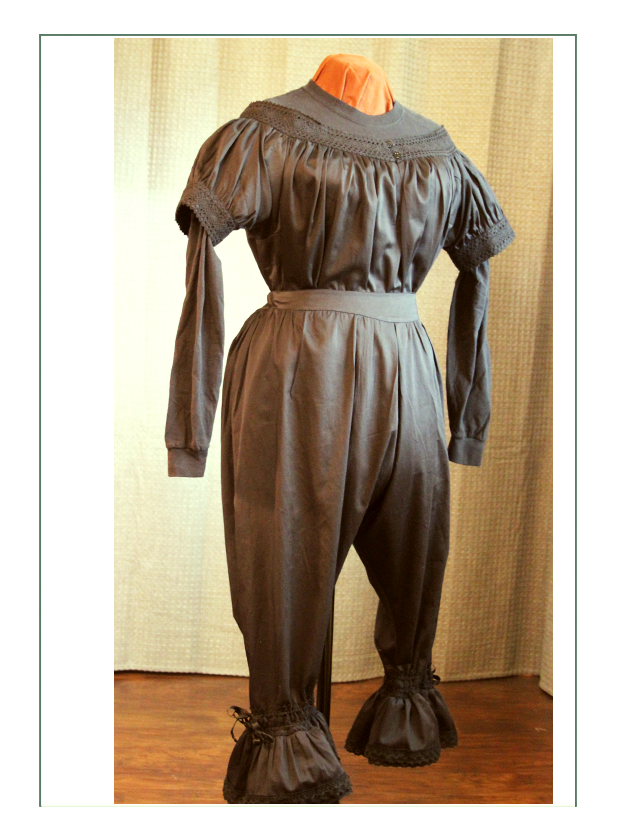

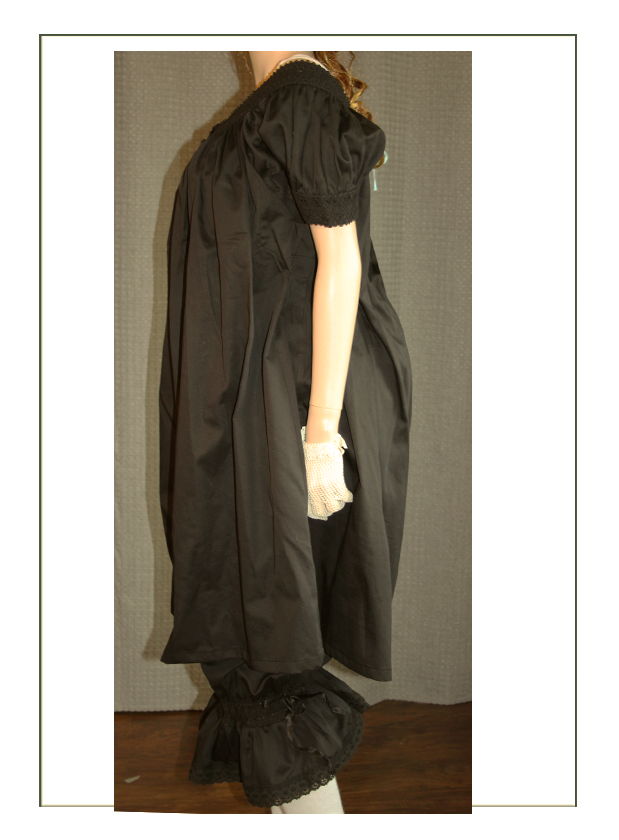

Split Drawers

Functional and basic, these are oh so soft and very washable as the bottom most layer. We made these with the correct longer length of the ’60’s with adjustable string tie in a casing at the waist. While the skirt will be wide all around, it was still desired to have a smooth center front since these will be worn under the corset and lumps might make it uncomfortable, or might bend the straight busk.

These are open all the way from front to back, with only a slight pleat to hide the split and overlap center front at the waistband (unlike later versions which had a faced inner leg and drop or bib type front that was more like a man’s 18th c breeches).

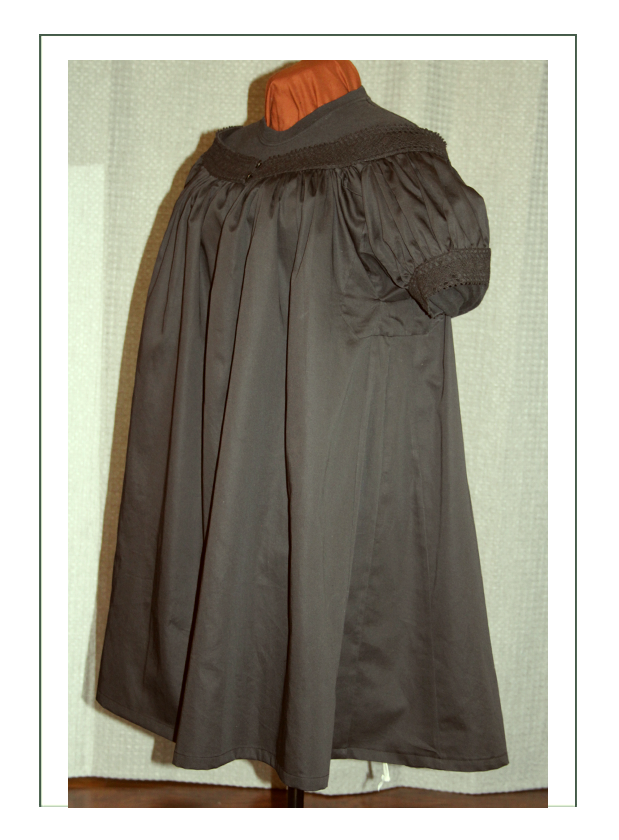

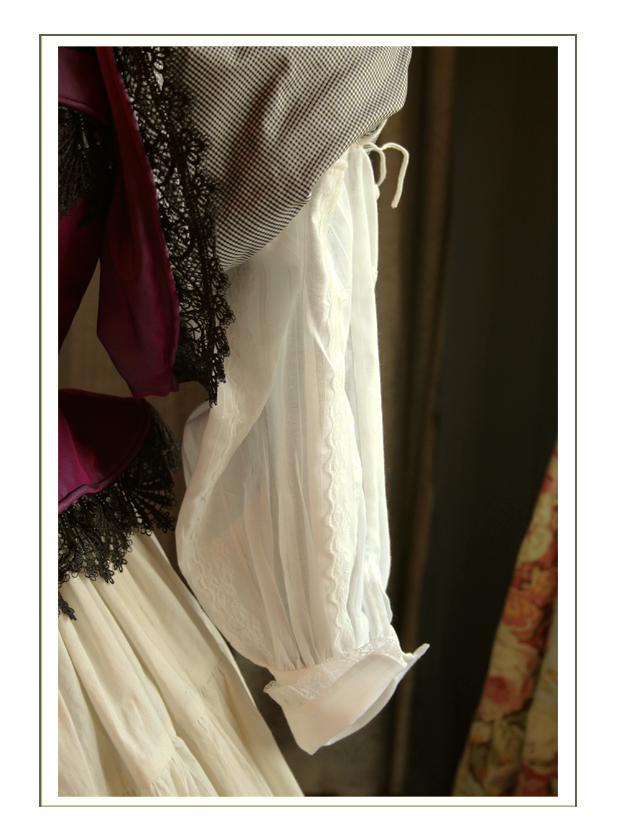

Chemise

Worn this way (tucked in):

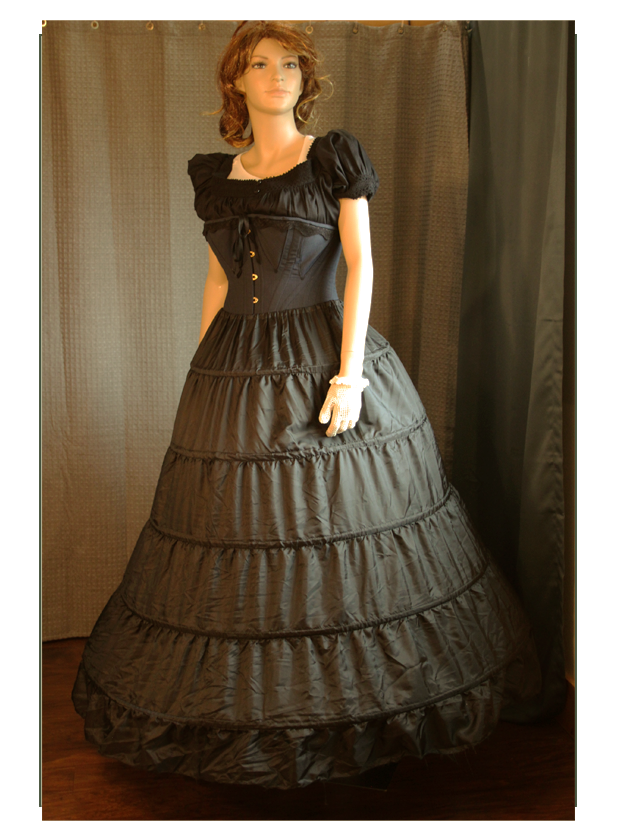

Crinoline Hoop

Women were not supposed to have feet in this decade. The appearance that the mannequin is “floating on air” is no accident or trick photography.

Petticoat

The ruffle on this petticoat is 17 yards, and the circumference of the body is 165″. That means, the skirt has to be even bigger! Also note this has a slightly dropped center front waist to keep the front lowered point of the bodice from sticking outwards. We did 18th century flat pleating to reduce the bulk around the waist as the skirt will hve cartridge pleating that will be quite full.

There is a twill tape through the entire waistband to give support so it doesn’t droop anywhere.

What is most interesting is the “floating body” – again, like with the hoop – that is NO ACCIDENT! Women weren’t supposed to have feet at all in this fashion era, and feet were actually erased from portraits. We didn’t have to . The camera flash gives this optional illusion.

This petticoat is shown worn over the crinoline hoop from above.

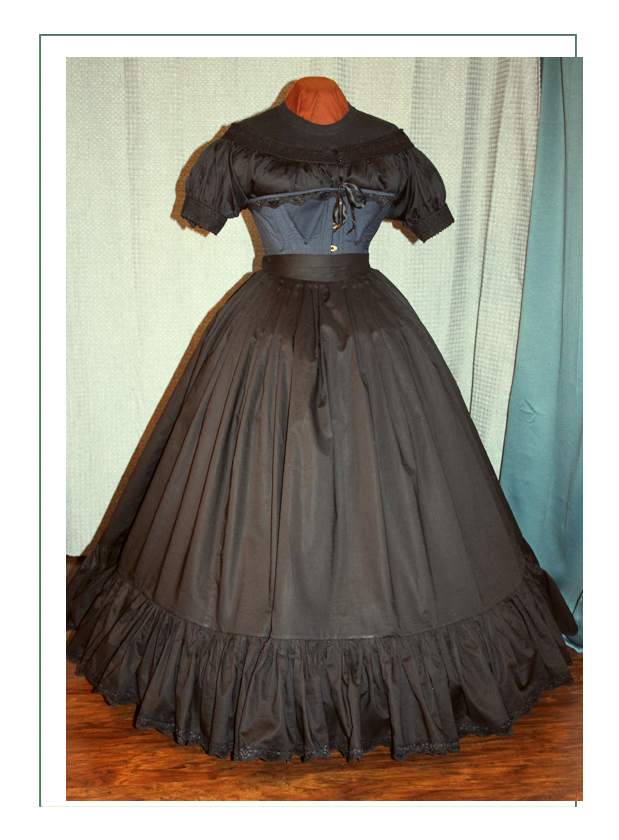

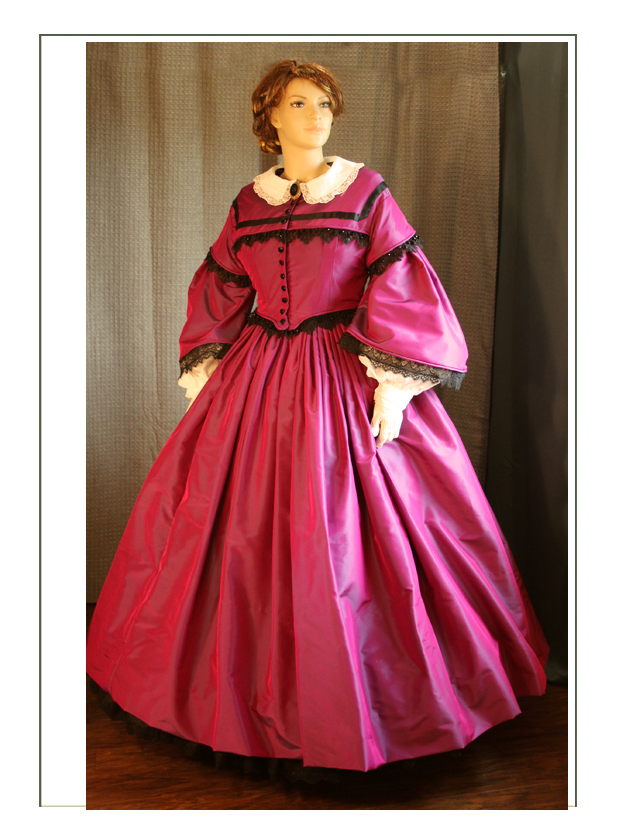

Dress

At this time there were many “correct” ways to build the “dress” – one piece, two matching pieces, or two not matching pieces. We are following the lead of Mrs. Keckley and building this historically accurately. While it would have made sense she would have separate bodice from skirt so she could wear the skirt with different tops (which she probably did with her regular day wear), this is a high end day wear dress as she would wear to attend to Mrs. Lincoln in the White House during events to which she would not have been invited. The two parts are basted together with front closure by hook and eye with false buttons, appearing to be one pieced dress. There is no separate skirt and bodice as a result.

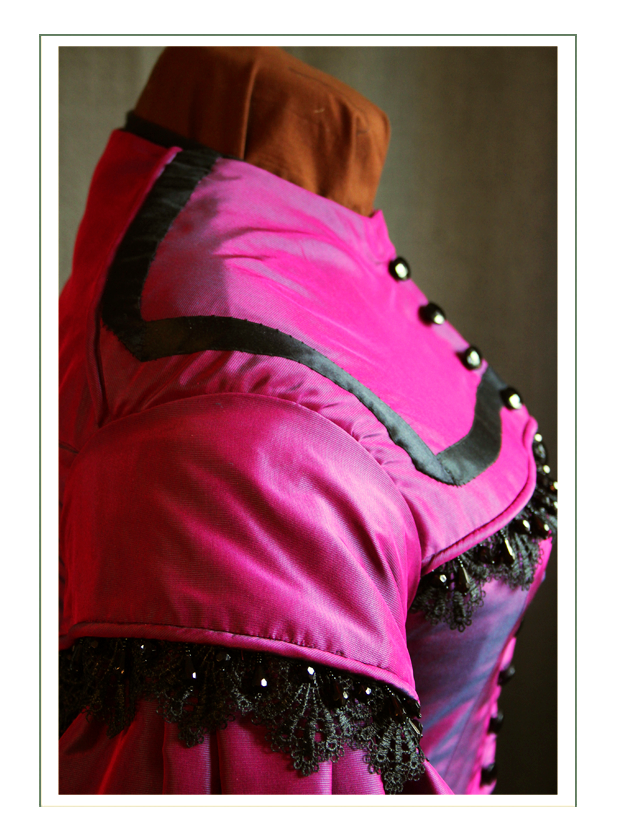

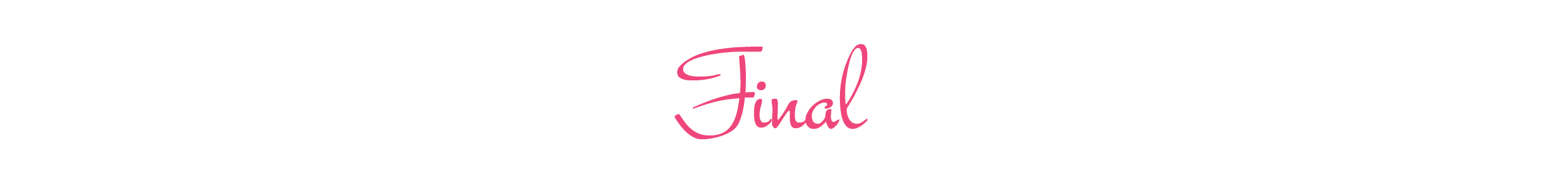

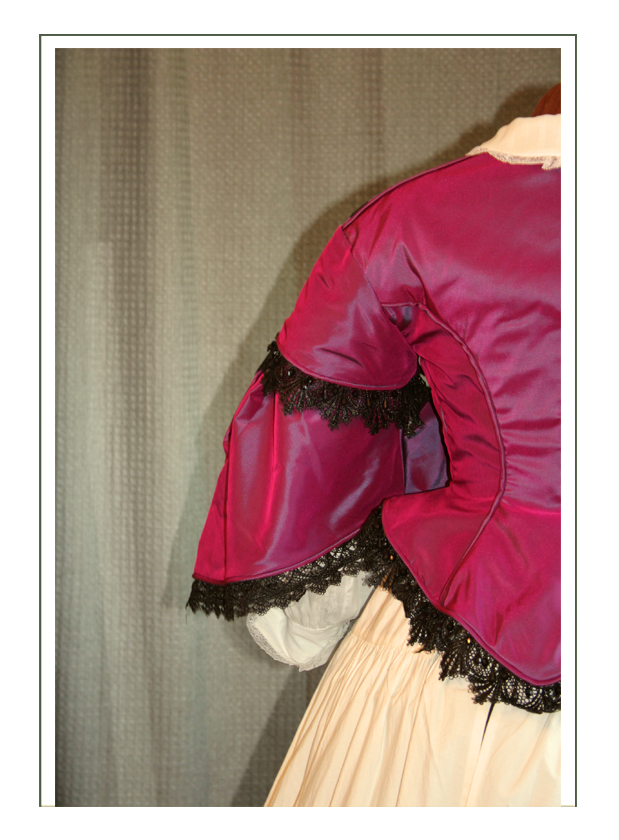

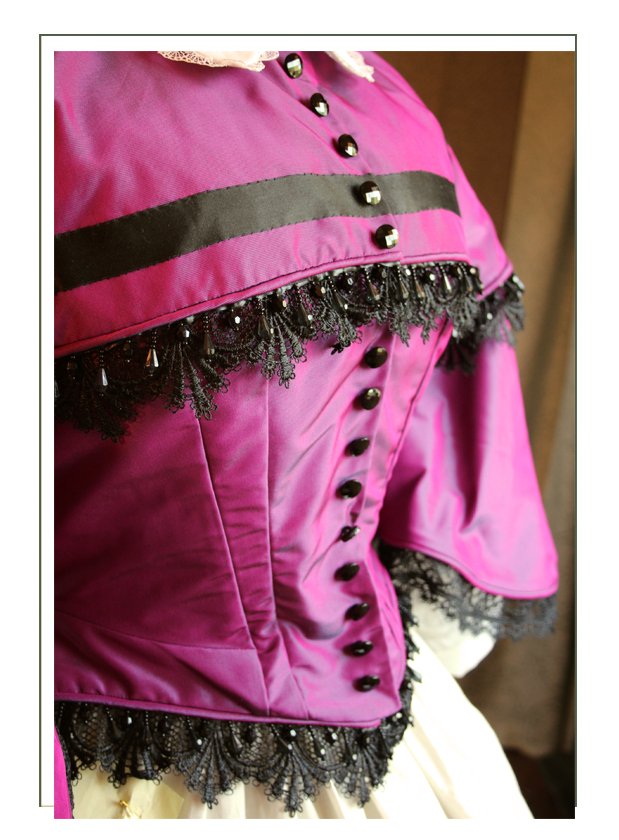

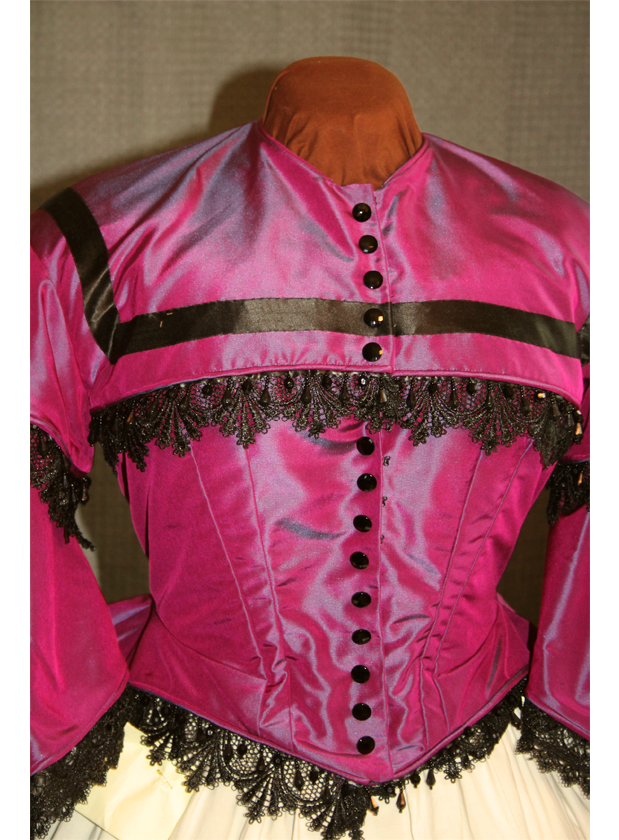

Bodice

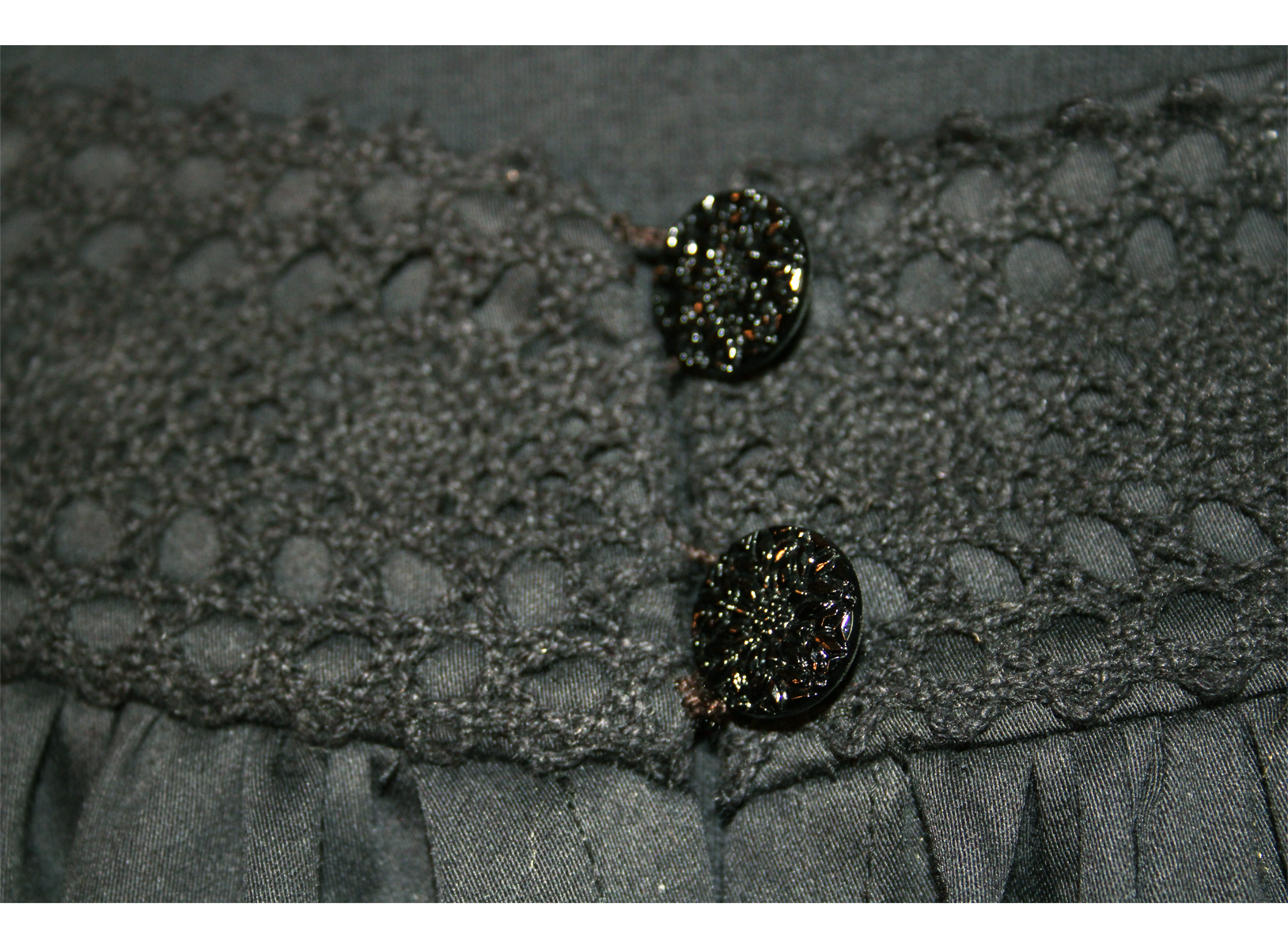

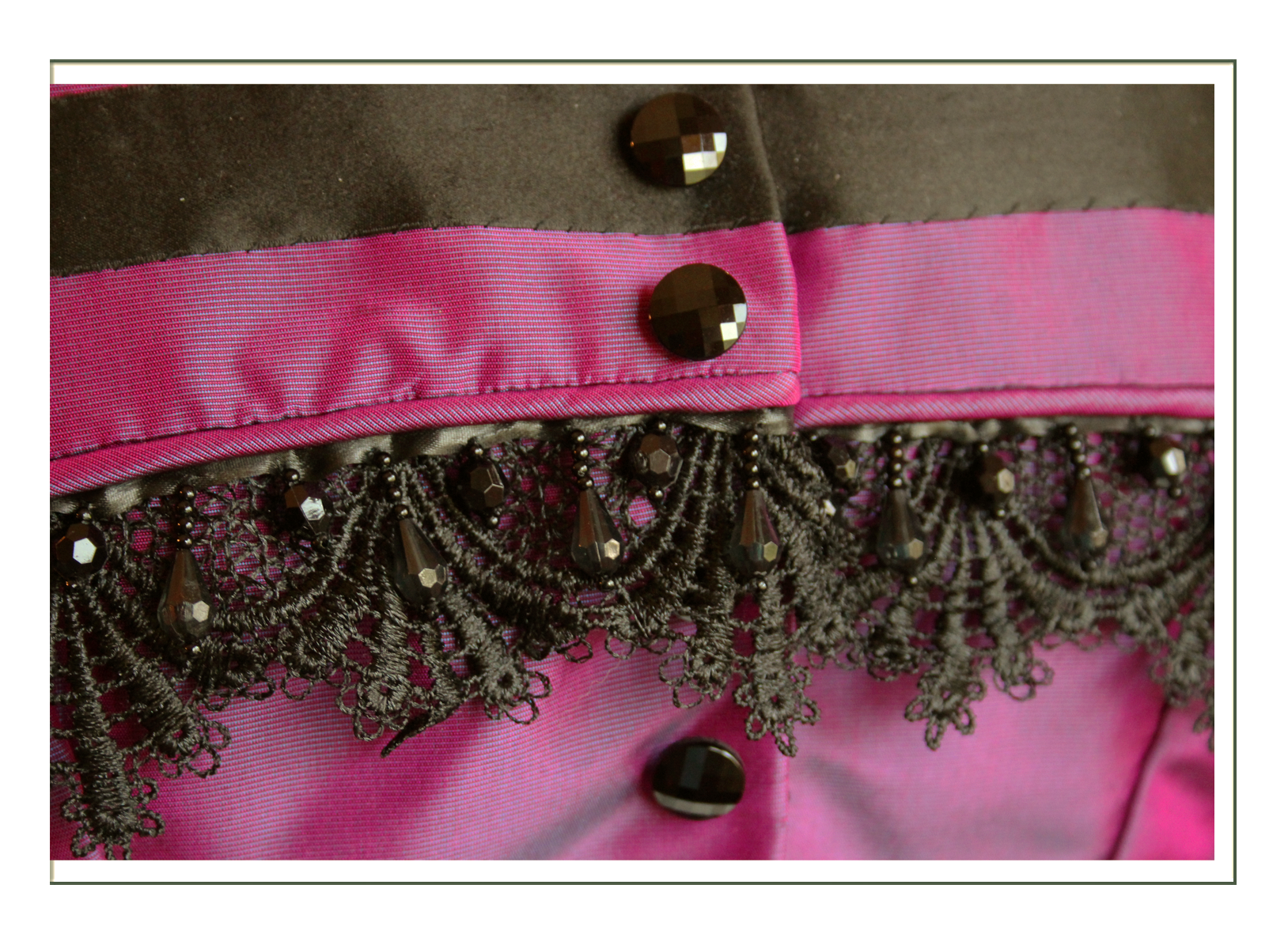

The bodice is first shown over the petticoat without undersleeves or collar. It has hook and eye closure up the front under false buttons, with beads and lace with piping at seams. This is an original (and difficult0 trim design to implement because we integrated it into the seams. In the 1860’s, they would have made “faux piping” rather than real, and trim would have been just “stuck on”. The seaming made the bodice get smaller and smaller because of bulk, so we are afraid we will need a remake.

the weight of the skirt will pull the waist down closer towards normal position. The petticoat and hoop have been loosened to wear lower down on the hips to reduce bulk at the waist.

The color is actually purple, but the flash from the camera and natural sunlight caught the warp and weft weaves (pink and blue) at different angles so it appears pink in these photos.

That’s 100% silk satin ribbon trim, and the fabric is 100% silk taffeta reproduction (stiff) type.

The most interesting thing is standing next to this in the shop, it looks and feels like we are in the Lincoln Museum i Springfield, Illinois! She’s tiny – with a tiny waist to be sure!

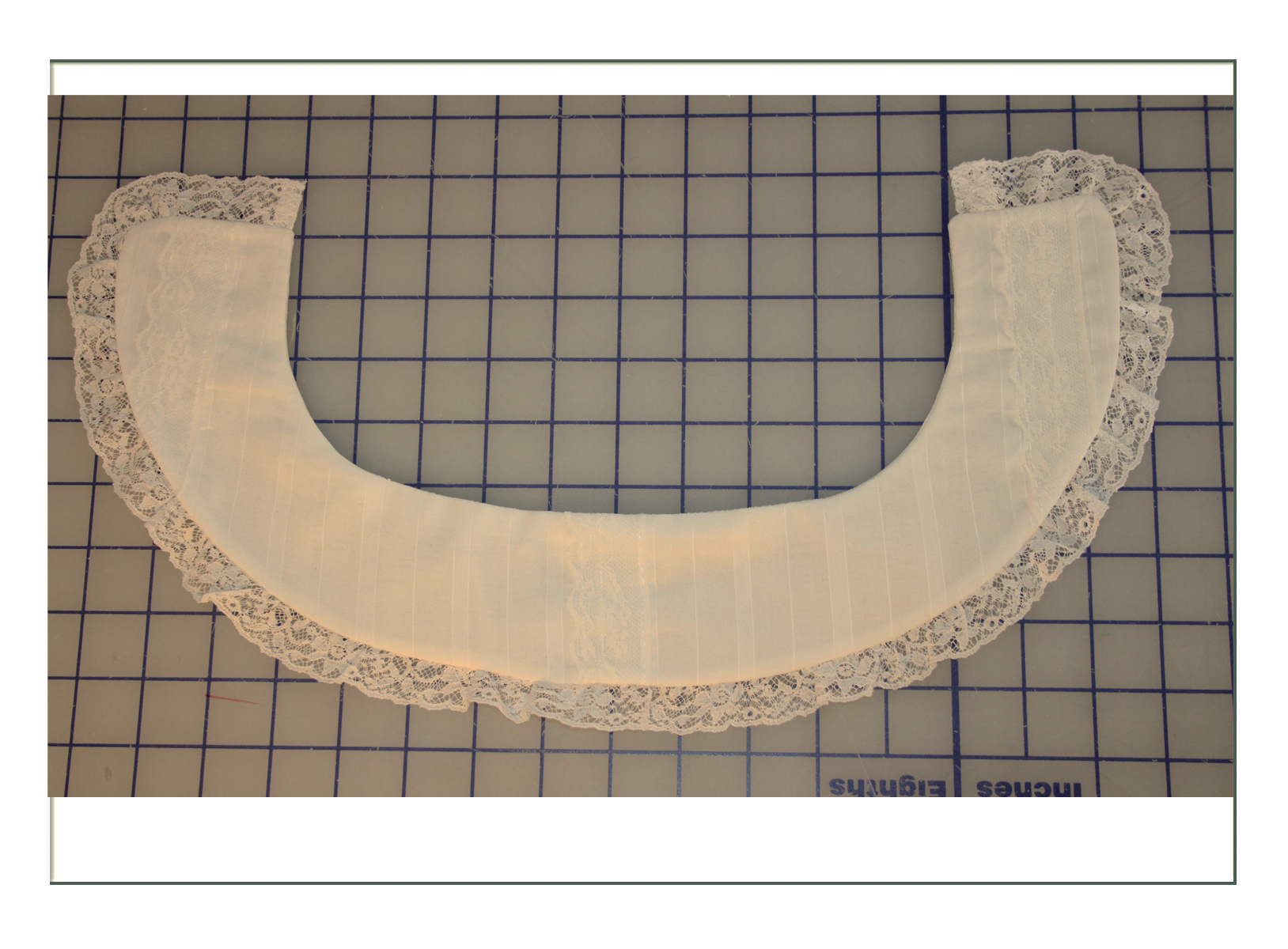

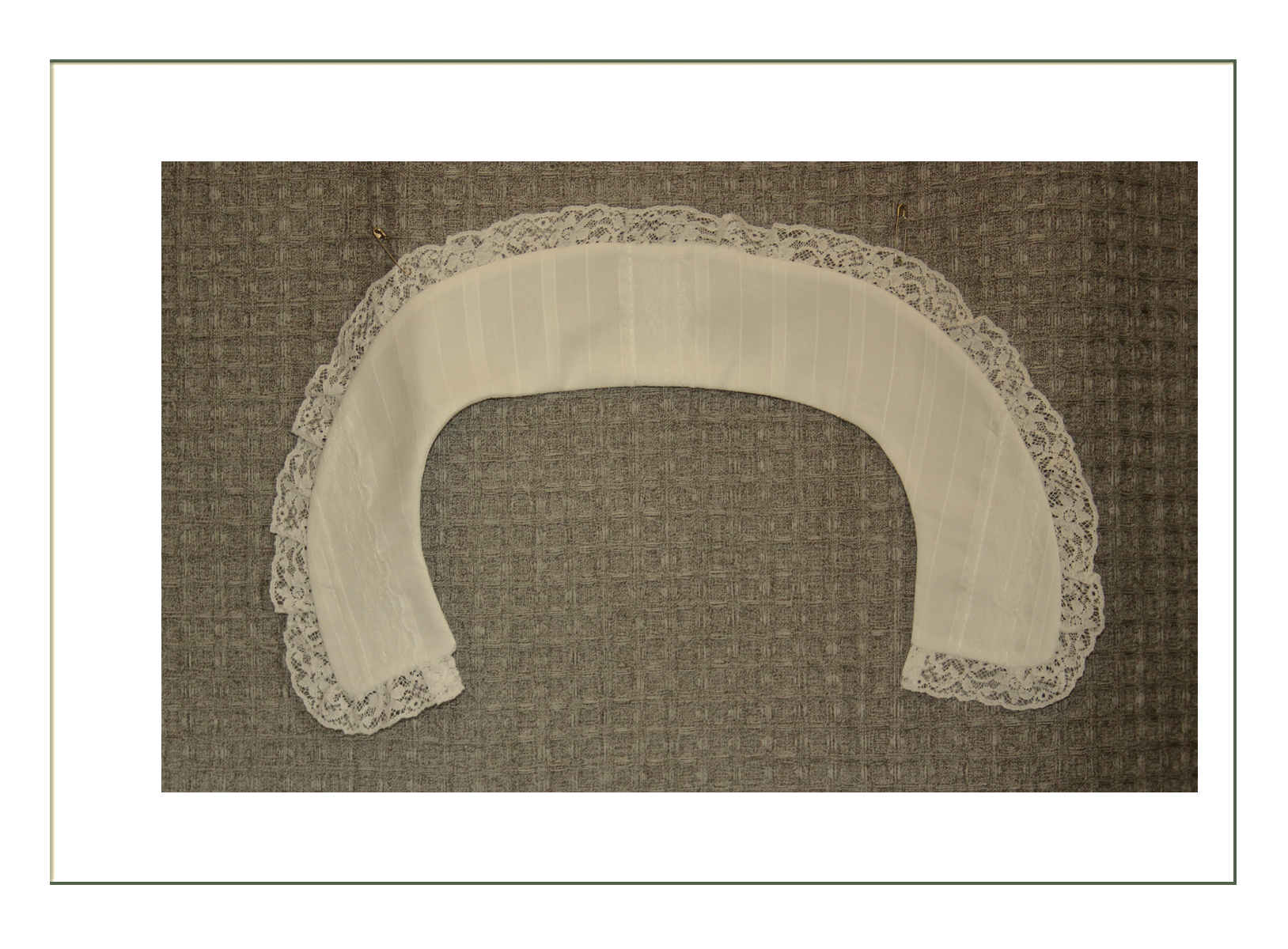

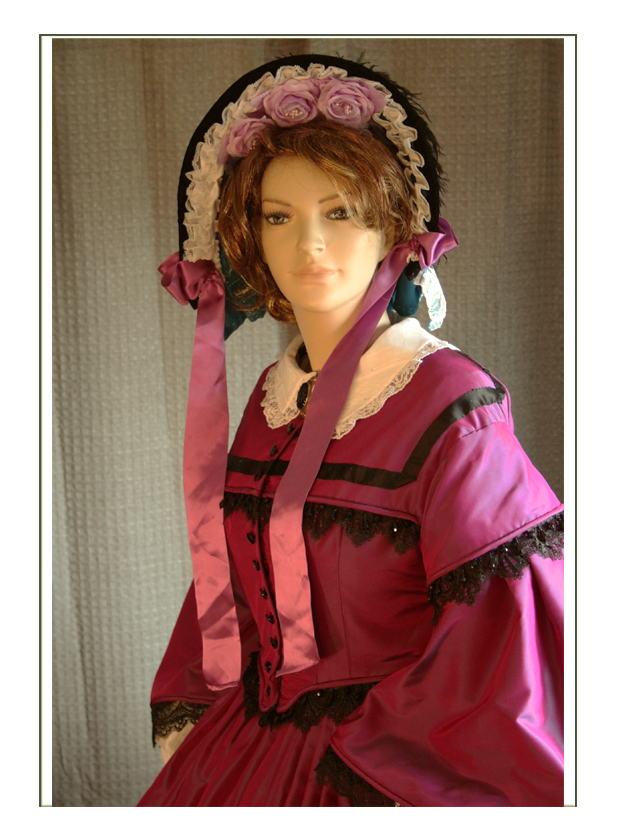

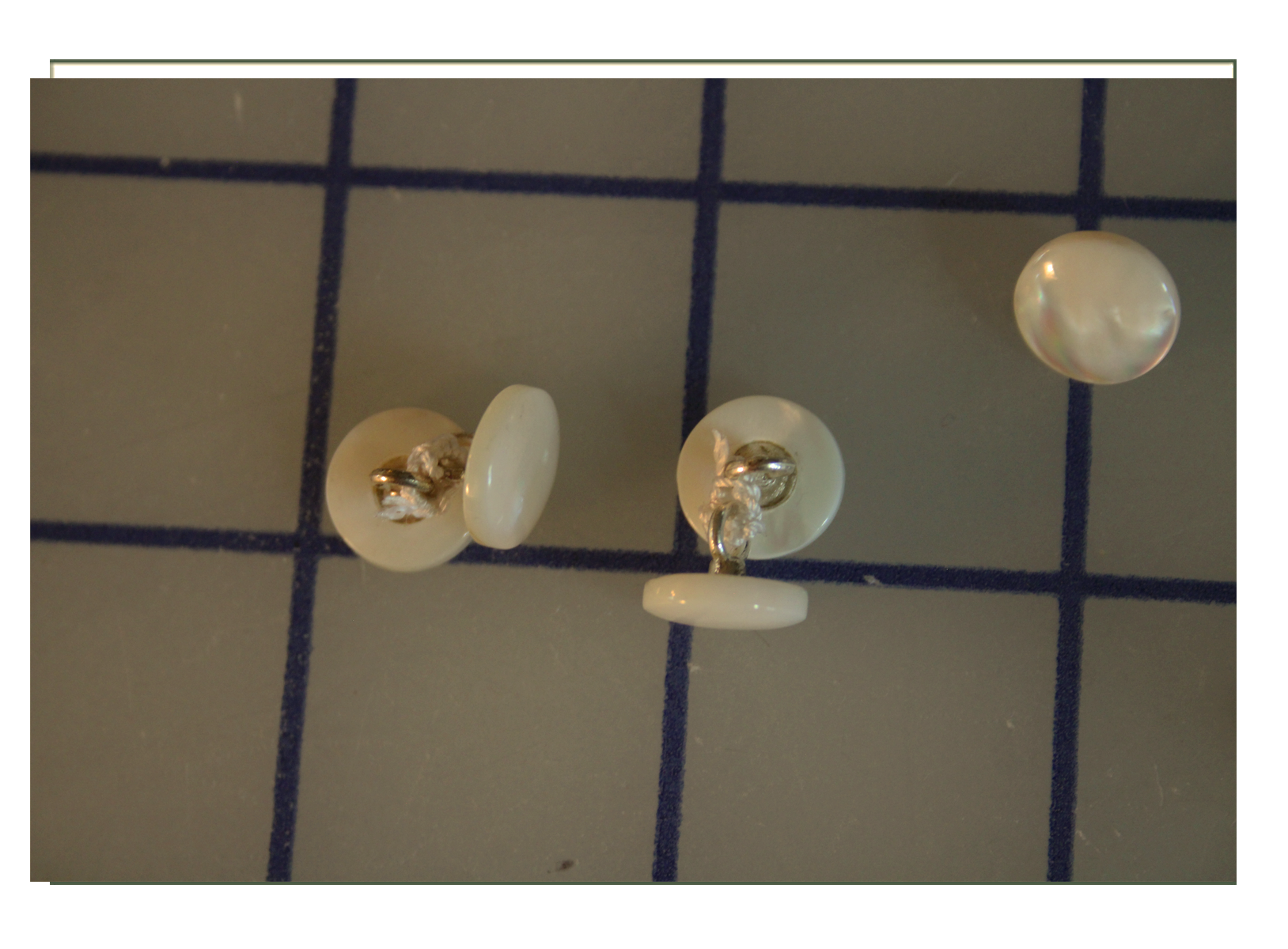

Collar & Engageante (Undersleeves)

The collar is loosely basted to the bodice, and the sleeves are pinned in. This allows a woman to wash these regularly while virtually never having to wash the rest of the bodice.

Attached Skirt

This too is loosely basted to the bodice so that it can be changed, swapped out with a different one, or cleaned. The skirt sits on a waistband of simple twill tape that is hand sewn to deep cartridge pleats and then based inside the perimeter of the bodice.

Because the bodice dips in center front and center back, the top of the skirt (just like they did in the 18th century when they adjusted the TOP of the skirt to keep the hemline parallel to the floor!) actually swoops up and down as it goes around the body. There are more pleats in the back to create the more “ovoid” (asymmetrical shape) of the 1862 crinoline since our crinoline hoop is actually symmetrical. The skirt achieves the rest of the “trompe d’oeil” (“trick of the eye”)

The hook and eye closure is at side front, and is hidden under the pleating. This method of skirt attachment is historically correct, and a bit tricky to put on.

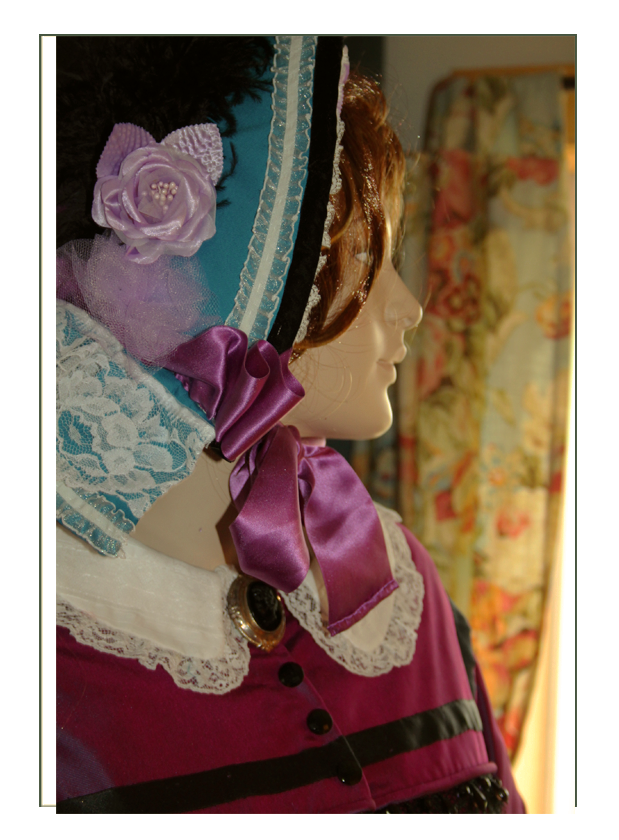

Bonnet

Intending to use the base to redesign and cover, we decided to keep this intact as purchased. It came from a milliner who had gone out of business, and the plan was to completely remake it. When Dr. Anderson saw it during a video chat though, she wanted it as it is. It’s actually better to have bonnet that is not exactly made out of the scraps at this time. It’s more consistent with a character who would not have owned a lot of bonnets; just a few functional ones and perhaps one fine one like this.

We did replace the ties, which can be worn tied in a bow, or hanging long. Either way, a hat pin will be required since we are not using a hair net. We saved a plain black antique one for this.

The ties are worn tied or untied and hanging loose as shown. The ties and ribbon are 100% silk satin. Roses and white trim are polyester.

Vintage Gloves

These are most likely from the 1940’s or ’50’s, but the hand crocheted cotton is perfect for 1862.

Bust Pads

Fill he gap where the shoulder meets the breast to make a smooth transition between the dropped sleeve and the front of the bodice. We note extant garments are always ripped at this point. It was indeed a stress point in the building of the bodice.

These are made of the silk lining with 3 layers of organic cotton batting sewn together like a contour map.

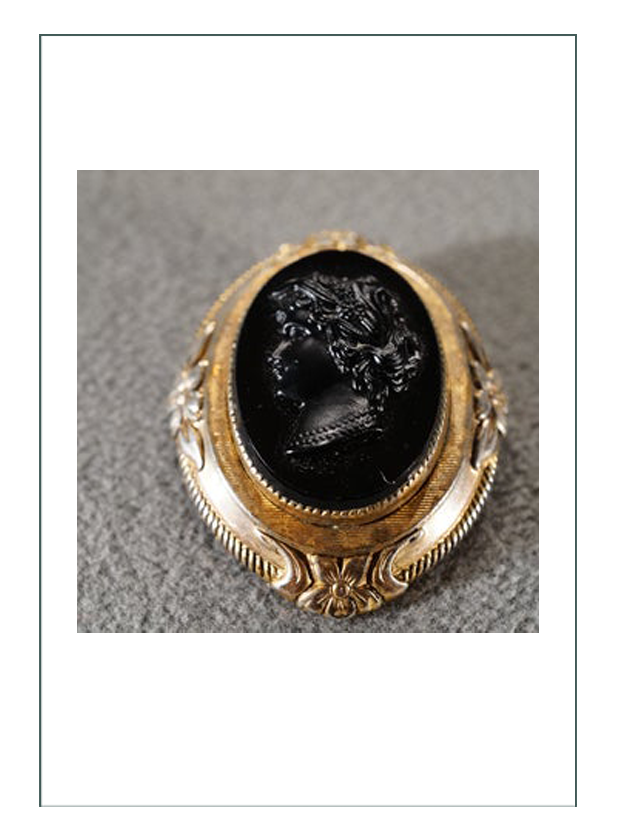

Antique Cameo Pin

We switched to a higher contrast antique black glass cameo with more “bling” to it, because the original abalone shell which was a lovely purple, was not high enough contrast to work with the buttons and beads.

On the Mannequin

Dr. Anderson tried on her ensemble and everything was perfect! Except.. the bodice. It just didn’t seem right. We had some fun with playing in the yard and house, but after that it went back for a complete remake of the bodice, undersleeves, collar, and skirt. The new design would have a peplum and a longer line, and the skirt will not be integrated with the bodice to avoid pulling and to make it easier to dress without assistance. Sleeves have a cuffed design, and the shoulders are re-designed for a broader back. The good Dr. will not have to worry about a tight cinching for comfort in wear all day long. Doesn’t the color look fabulous??

Revised Construction – Completely New!

Variations in design include: wider sleeves, cuffs on engageante sleeves, pointed collar, longer beading and lace, bodice peplum, skirt separate from bodice, skirt with tapered waistband and cartridge pleats rather than knife pleats, and the biggy – a rump pad to bring the ovoid shape out under the peplum!

The result seems to be a more “Antebellum” look – closer to the mid to late 1850’s, rather than a true 1862 silhouette and look. It also has the look of a St. Louis or New Orleans. This is appropriate as Mrs. Keckly was in St. Louis in the mid-1850’s earning her freedom!

On the Dressmaking Dummy

All

Bodice

Rump

Collar

Sleeves

Skirt

Final & Revised – Dr. Anderson

Click here to go to the 1862 Historical Context Page (next)

Click here to go to the 1862 Fashion History Page