(Continued from the History of Stays & Corsets Introduction/Overview and the History of Stays 1740-1780 Sections)

A New Silhouette 1780’s Forward

France Leading Fashion

The Regency Era

1780-1800

Women’s fashions at the turn of the 19th century display the results of the Napoleonic Wars, inc which fashion absorbed influences from the Middle East. Exotic fabrics, turbans, transparent cotton muslins, feathers. exotic jewelry, and a taste for Classical Greece followed.

This era was known as “neo-classical revival”, and it had an overwhelming effect on fashion. Women wanted the light and diaphanous fashions like Greek statues. This was the period written about by authors such as Jane Austen.

In France, there were traveling weavers who introduced lovely striped fabrics that were actually an innovative way to use up leftover yarns from other weaves. The French peasantry, wearing these, so charmed Queen Marie Antoinette that she introduced new fashions using them.

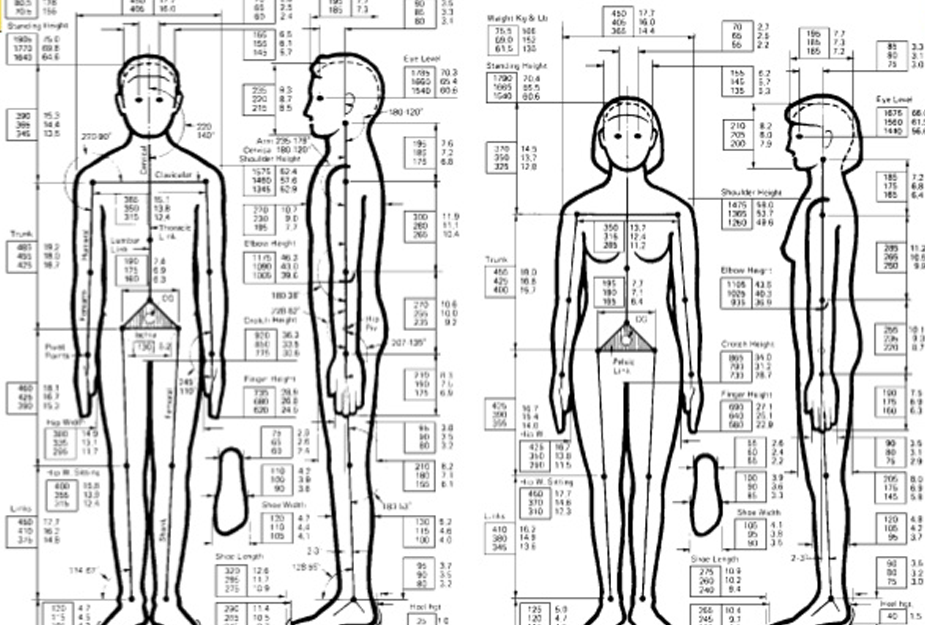

By the end of the 18th century, France was at war, and an abrupt change came to all structured and elaborate garments. It was at this time the scientific study of the human body had come to the garment making industry.

It was discovered the body was in proportion to head measurements. W.H. Wampum, a German tailor was fascinated with this law of Anthropometrics, and began to work with the idea of drafting patterns to size rather than draping on the body.

As society was rapidly growing more urbanized, the demand for mass production demanded “proportionate” systems to speed up the trial and error of previous methods. The fitted garment became the norm.

In spite of restrictions placed on the import and usage of printed cottons coming from India in England and France at the time because those countries wanted to support their own textile industries, cotton became wildly popular. Cotton quickly replaced silk, wool, and linen. By 1759 France and 1774 England had given up and removed the laws.

In France, the leader at the time of world fashion, social order had been completely overturned during the French Revolution. With it came a loosening of morals and deportment. In France, the new, clingy, near-naked fashion silhouette was more popular than other places such as England.

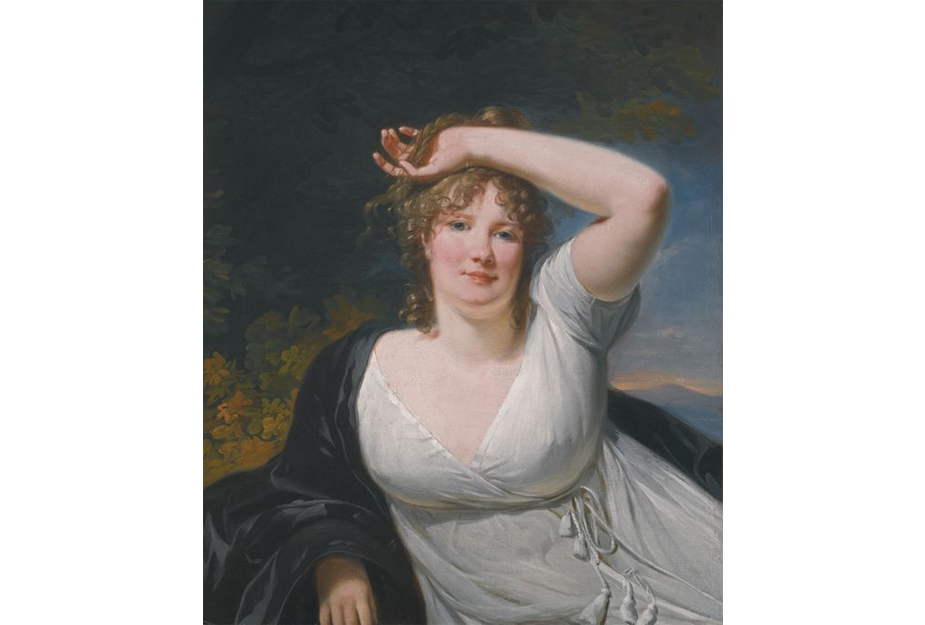

Writings of the English and French, however discuss that stays were worn or not worn in equal measure. Young women and those with beautiful figures discarded undergarments, while those of “bountiful flesh” or older and gravity drawn shapes continued to wear some sort of understructure.

A New Figure

1800

At the beginning of the 19th century (1800) the Grecian figure, or the natural body with high rounded breasts and long well-rounded legs and arms was the ideal every woman strived to obtain. Neo-classical fashions demanded a more revealed and youthful bosom in its natural state.

The new soft, light cotton muslin dress clung to the body, showing every nuance and every contour of her shape. This meant some form of support would have to lift the breasts. It also meant small women or older or less endowed women might need some type of padding or augmentation.

Heavy, thick, or extra undergarments were discarded though, as they distracted and ruined the “natural” body shape, and so the boned stay lost popularity with the woman trying to obtain the “fashionable” shape of the day.

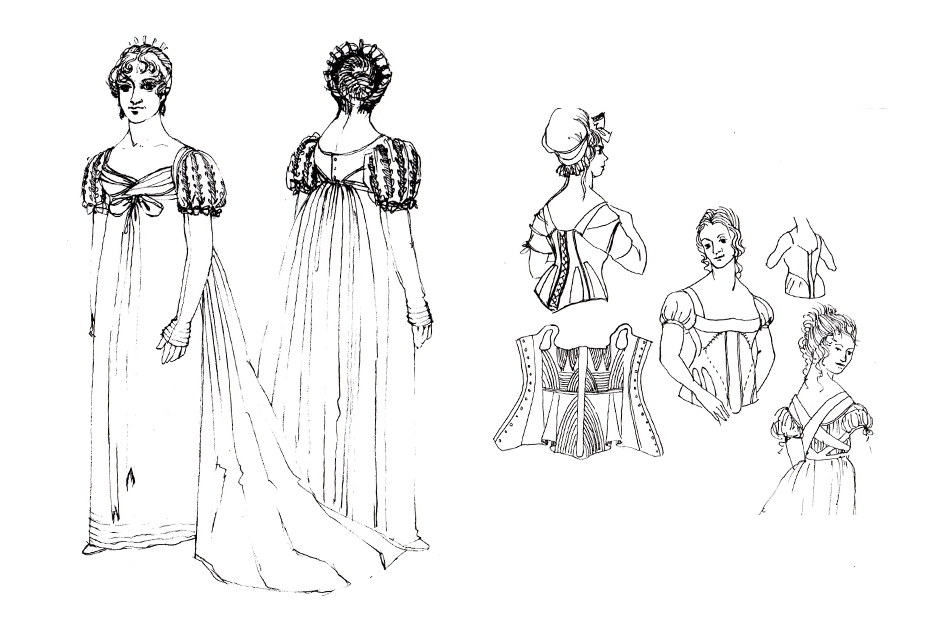

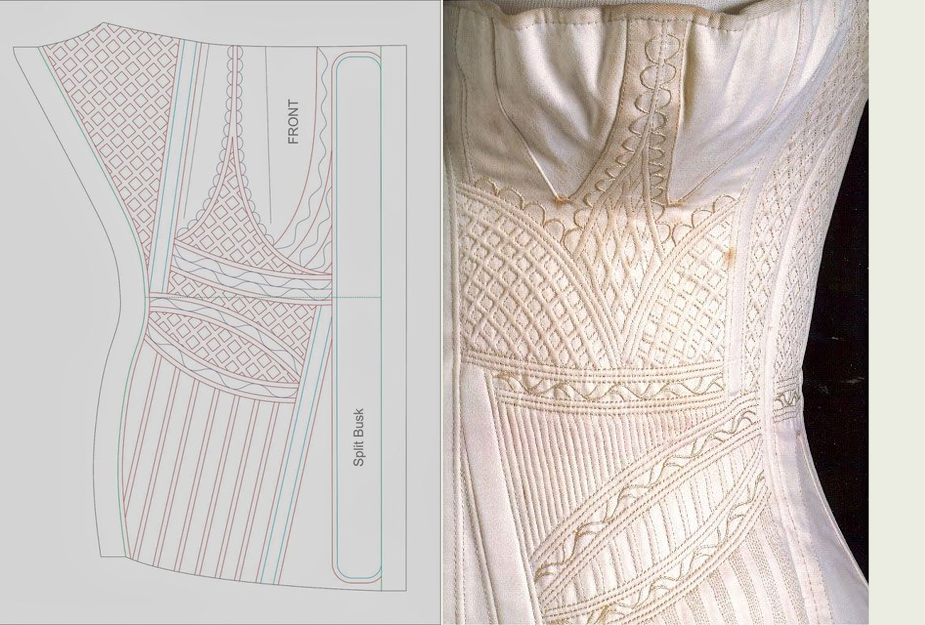

The light early Regency or Neo-Classical corset has gussets to enhance the bust and hips with light bones or cording to facilitate lacing. These had a central, usually hard wood tapered busk, up the center front to assist in pushing the bust line up into a prominent position.

This was the first time in history the “corset” was a pieced and complex garment. Gussets, which assisted making the breasts and hips “rounded” were the beginning of innovative cutting techniques.

Stays or No Stays

At first dresses made of cotton were of the same fashion lines as stiff silks, but gradually with increasing use, the looser, simpler, and plainer style of dress began to evolve. The simple cotton muslin dresses of the 1780’s had wide sashes. By 1793, the sash narrowed and the waistline raised up.

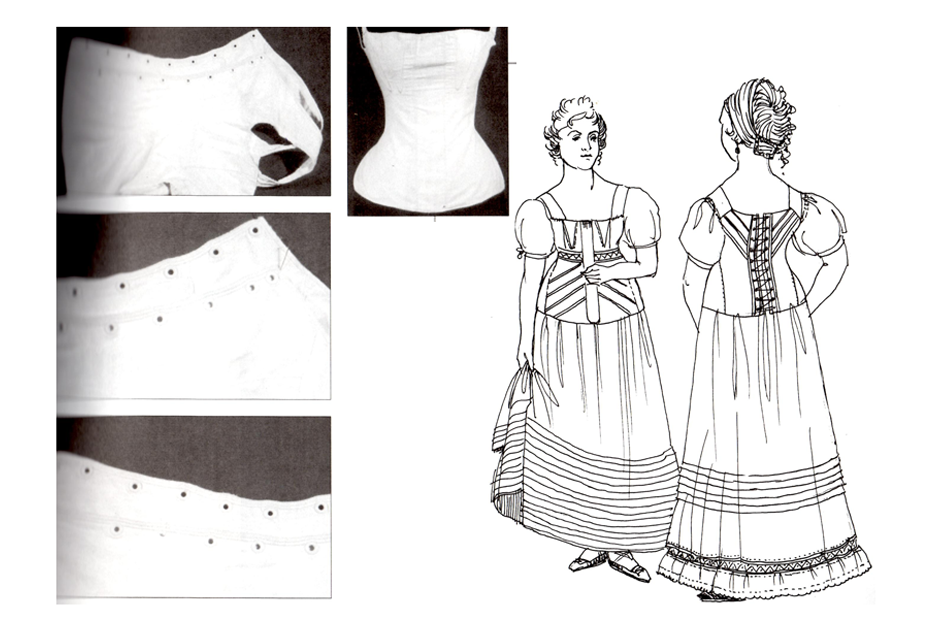

With these soft fashions and the new silhouette, simpler and lighter types of stays were worn. At first they were cut like previous ones but made of lighter and less stiff materials and bones, but as the body of the dress shortened, the stays began to shrink in size too. The back became short, and the front long. Tabs at the waistline were eventually discarded entirely.

Some early Regency corsets were fully boned, others half-boned, and some not boned at all.

At the end of the 18th century, the chaotic aftermath of the French Revolution and worship of antique fashion would simplify the dress still further. All extra material was gotten rid of in both dress and stays, and by about 1808 for most women, stays were just a simple band or were not worn at all.

The Imperfect Body

Many of the simple muslin dresses of around 1800 were mounted on a cotton lining with two side pieces that would cross over and fasten in front, providing a type of “binding” or support. It acted as a type of early brassiere, and for many women, was the only thing worn.

For those who could or would not go without, and especially in England where social norms and mores persisted, whaleboned stays similar to the late 1780’s and 1790’s continued to be worn well into the first decades of the new century.

The new early 1800 stays became longer to go over the hips in order to smooth the line to obtain a semblance of the vertical silhouette of fashion. The tabs were traded for hip gussets so they could be form fitting but still allow leg movement.

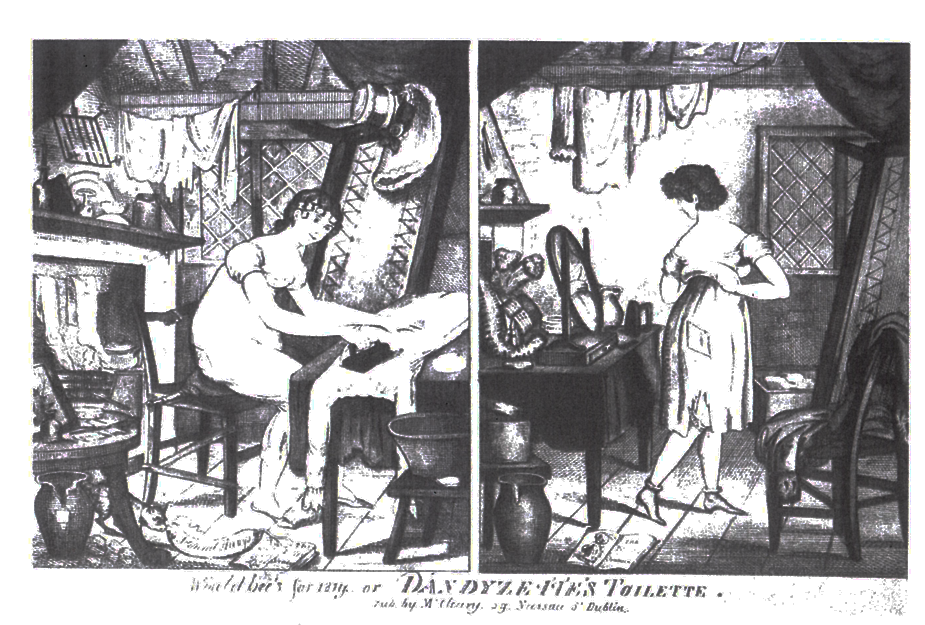

For the stout or heavily boned, these longer stays with lighter boning were reinforced with padding. This type of early “corset”, worn only to control the shape, were not considered fashionable, but a necessity of those without perfect figures. They were much ridiculed in English and French media.

Stays become Corsets

1800-1810’s

As this was the first time in history fashion basically removed all understructure, there were experiments with materials and methods and techniques aimed to produce the perfect Grecian ideal form. There was a long, knitted corset of silk or cotton.

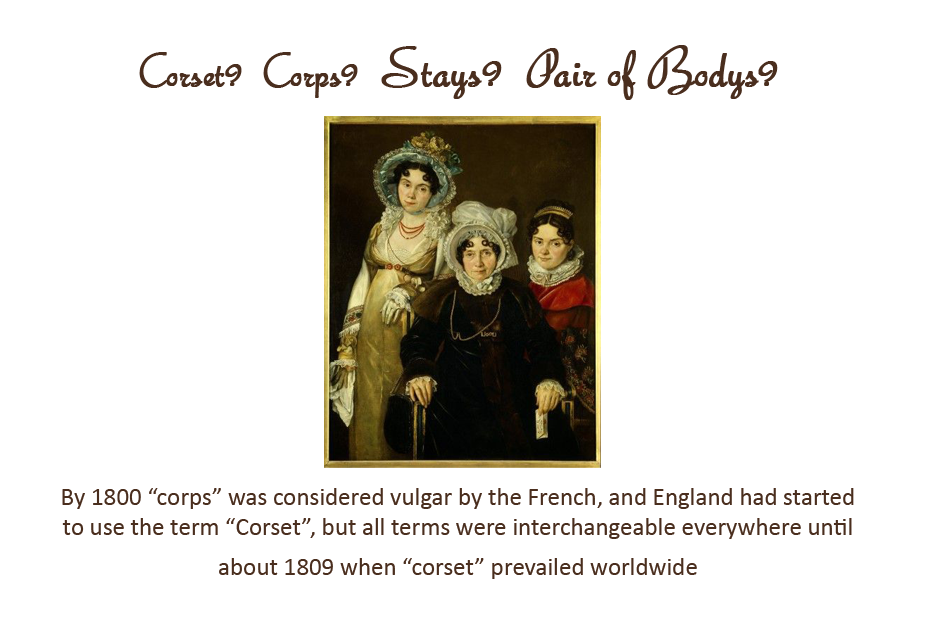

The old term “corps” had disappeared entirely, and in France this new undergarment was called a “corset” (“corps” now being considered vulgar). In England the old term “stays” was still used, although the English started to call them “corsets”. Until about 1809, both terms were used interchangeably.

In 1809-10 however, as the narrow and lower waist with wider skirts started to return, the name and use of a “corset” became more widely used.

A new type of corset began to take shape that was completely different than the preceding “stays” and the transitional Regency “corset”.

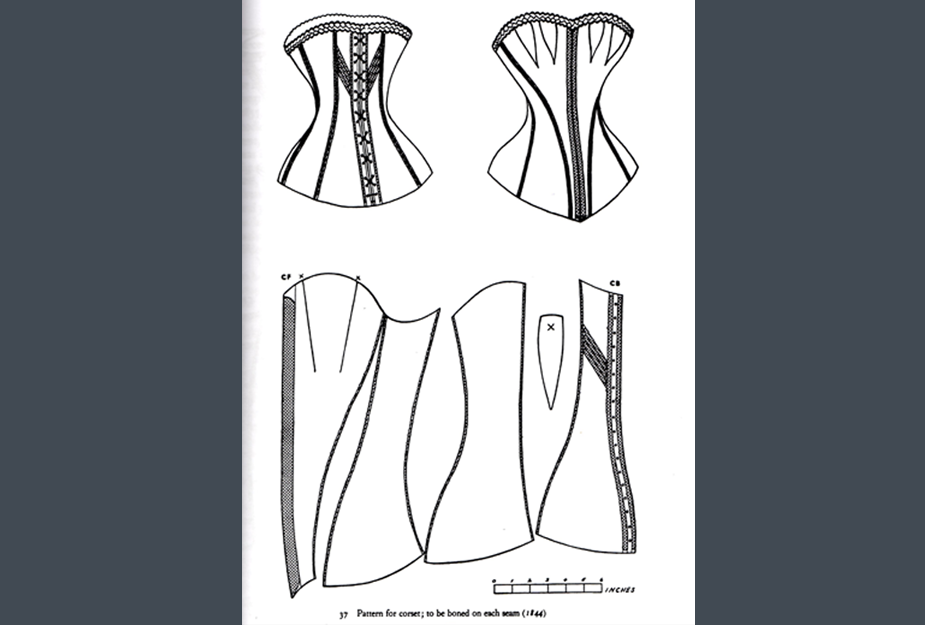

As the 2nd decade of the 19th century progressed, the emphasis changed from the 18th century rigid shaped body and the Regency flowing natural body to a silhouette with a small waist that had big curvy lines flowing out from it above and below. The use of bust and hip gussets assisted the flowing shape of the curvy body being emphasized.

Late Regency – A Shape that would Stay.. without Stays

1810’s

Beginning in about 1810, the new corset began from a simple body bodice made of a strong cotton material called “jean” which would later be known as “coutil” or “couteil”. While the waist was still high like in the early Regency era corsets, there were less pieces used.

Beginning in about 1810, the new corset began from a simple body bodice made of a strong cotton material called “jean” which would later be known as “coutil” or “couteil”. While the waist was still high like in the early Regency era corsets, there were less pieces used.

As the Regency era progressed, Roundness was now given to the bust by inserting two or more gussets on each side of the hips, and two or more gussets/gores in the bust. The idea was to create roundness and to lift the breasts.

As the 1810’s progressed, the waist gradually lengthened in the dress design and dropped towards the normal waist position, the corset lengthened too and became more defined. Extra side pieces were added for control and shaping.

At first, while the dress was still slender, this “bodice” was still far along on the hips, but it decreased in length as the skirt increased in fullness. By the middle of the 19th century, the bodice or corset became very short.

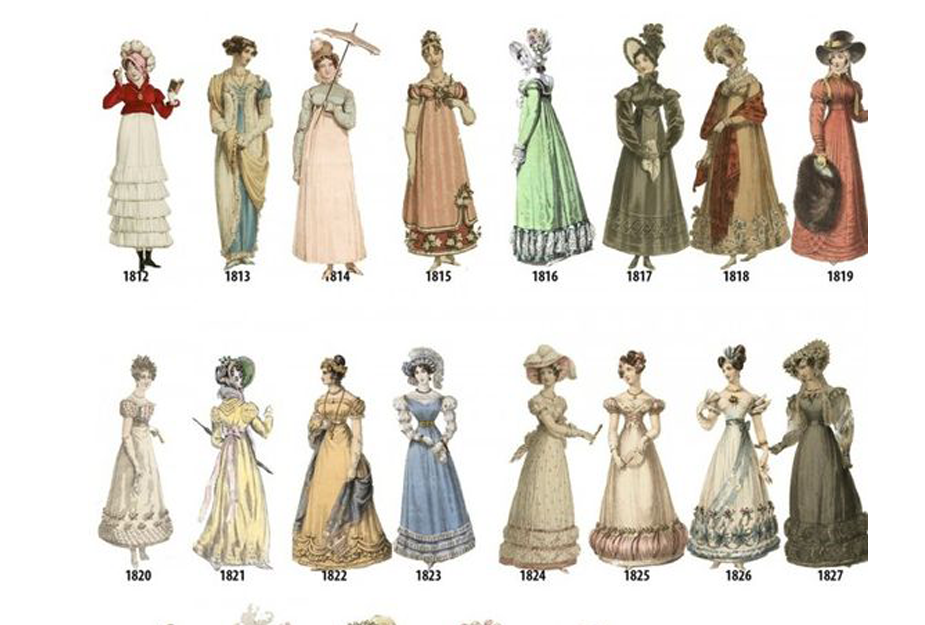

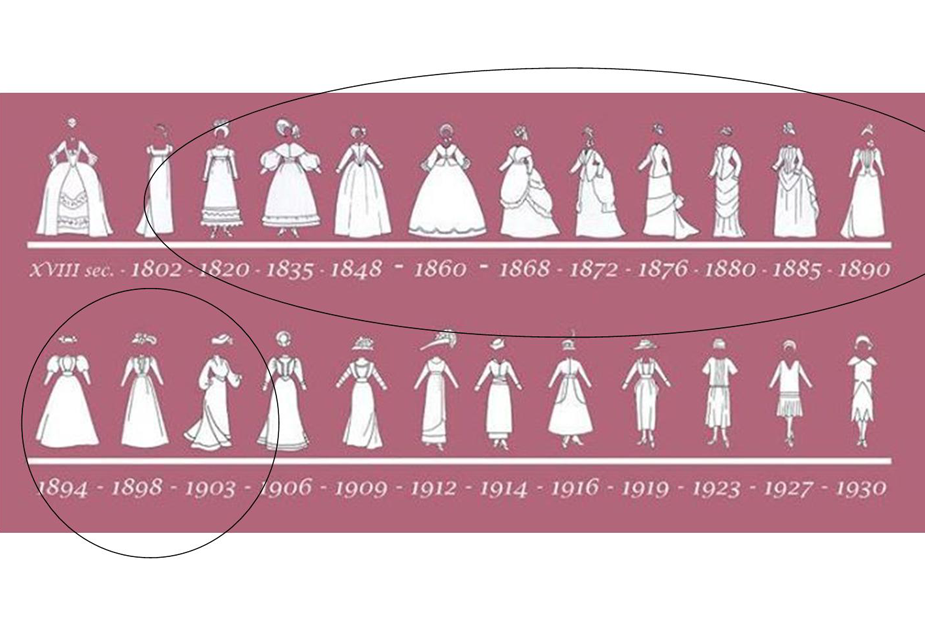

The long vertical look of the period was in strong contrast to the 18th century. The Regency silhouette became long and elegant with little reference to width. As the early Regency turned to later Regency, the dress became stiffer and wider, and the silhouette required a change in understructure.

Mid Regency

1810’s & 1820’s

In about 1820, ladies began to fashion quilted bodies with a slight re-enforcement from whale baleen to assist in developing the new shape of an extended skirt, lowering of the waistline, and a gradual widening of the upper sleeve.

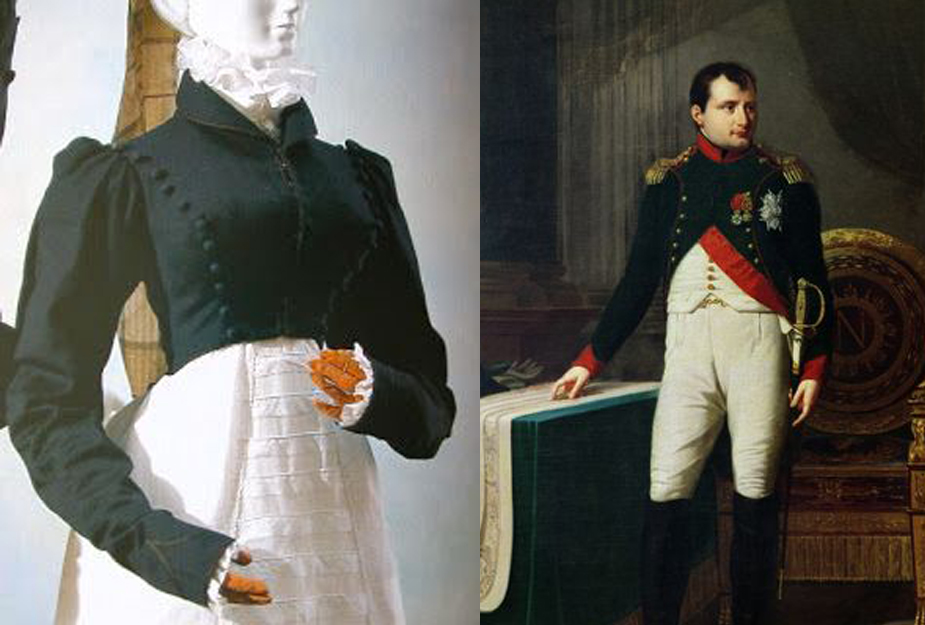

Military uniforms with their strong colors and rows of braid and epaulettes were copied into women’s fashion of the 1820’s, and began to influence the silhouette, which of course demanded a new shape to the undergarments.

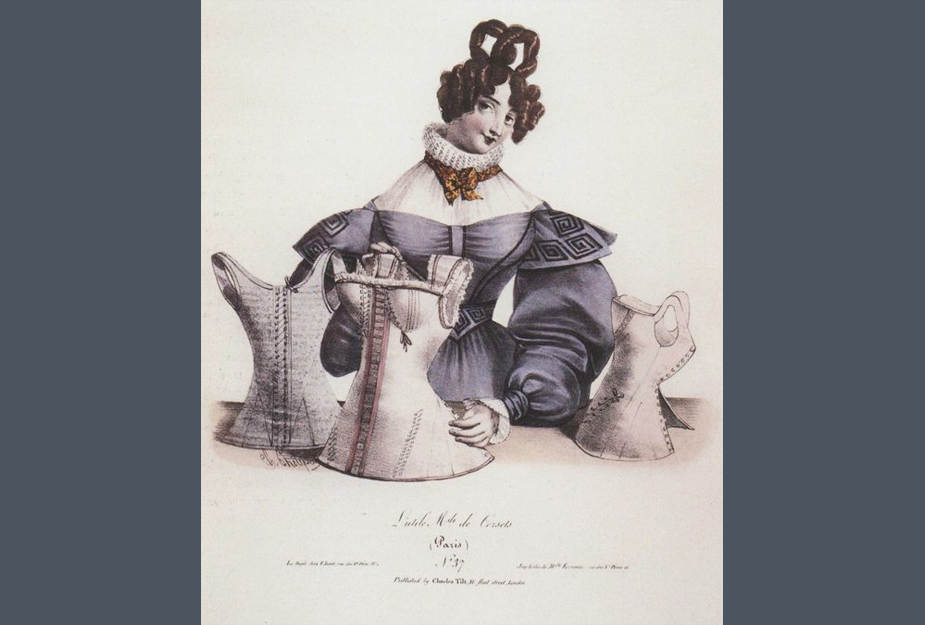

Two more examples of women’s military inspired Spencers below:

The new 1820 “bodys” helped visually reduce the waist size so the newer silhouette gave the wearer the appearanc e of having a tiny waist. It was this shift in proportion that would lead to tight lacing for the rest of the century.

The corset through the 1820’s became fuller in overall shape at the top, and took on a molded, shaped basque area below the waist.

It was at the end of the 1820’s that riding corsets were developed especially for freedom of movement.

A wooden stick called a “busk” in late colonials and Regency corsets, was much like today’s paint stirrer but much thicker and more durable. Typically made of a hardwood such as oak and maple, it was about 1/8″ thick and 1 1/2-2″ wide early in the Regency era, widening to 2 1/2″ later. Early it was tapered, while later it was straight.

The purpose of the busk was to distinctly separate the breasts to put them into the cups provided by the corset so they were clearly “two pert apples on a tray” to quote a cartoonist at the time.

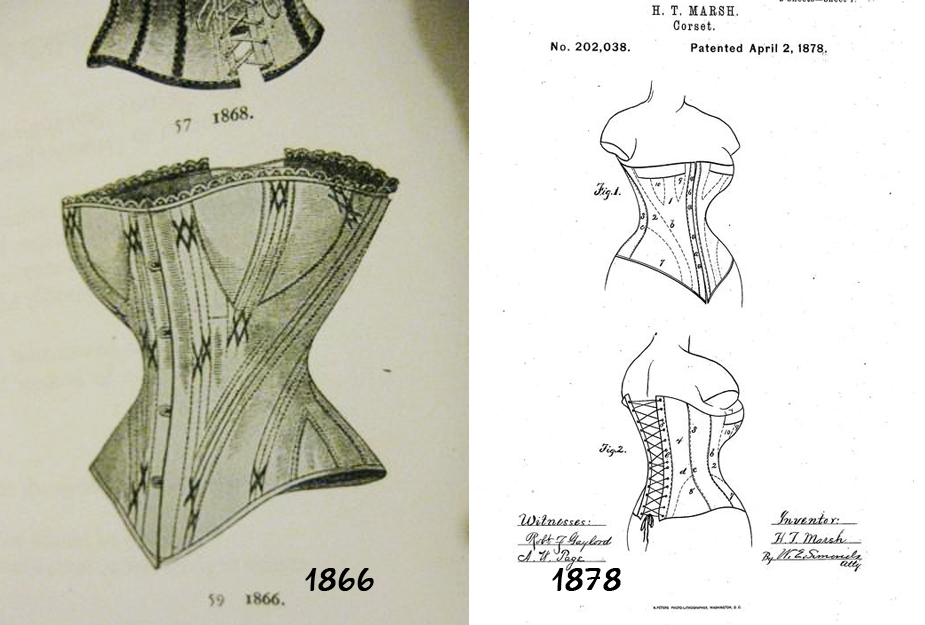

By about 1835, the flat wooden busk that was worn in the earlier Regency corsets to lift and separate the breasts became broad and was supplemented along the sides and in the center back to support lacing with whalebones.

For heavy women of the mid to late Regency era, side bones and extra back bones were added to support and shape a bit more than for slimmer women. Older women liked these too, as they were more like the Colonial stays they grew up with.

From the late 1820’s until the 1840’s, most corsets (general called “bodices” during that time frame) had shoulder straps.

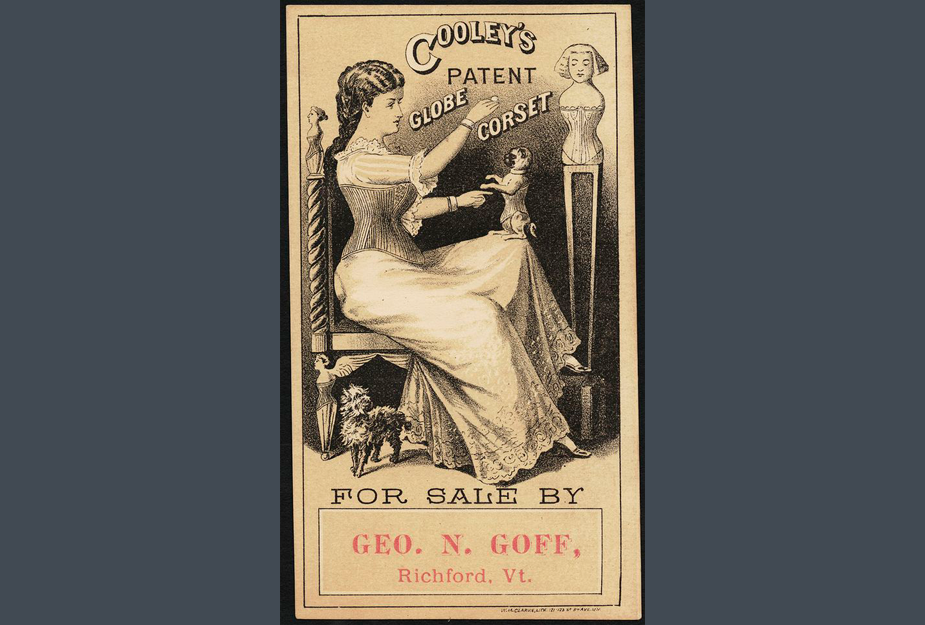

From the 1820’s until the late 1860’s, there were dressmakers who specialized in the making of corsets. These were called “corsetiers”. Most corsets, however, were made at home using patterns and instructions found in ladies’ magazines.

Homemade corsets always followed the fashionable silhouette of the day: long bodied from the 1820’s into the 1840’s, and getting shorter and shorter and more and more boned into the 1850’s and 1860’s.

Regency Becomes Victorian – France to England

1820’s & 1830’s

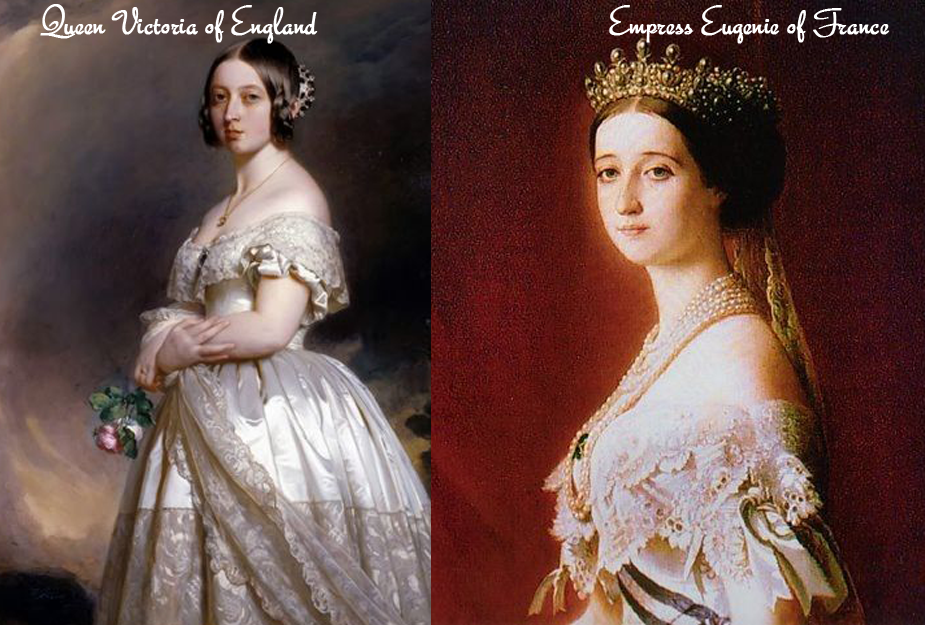

Although Queen Victoria is credited with what would become known as “Victorian Fashion”, it was really designer Charles Worth, and Englishman with a fashion house in Paris, that initiated the next revolution in women’s fashion.

Princess Eugenie of France was Worth’s customer, and Eugenie and Victoria were good friends. Charles Worth, Parisian designer, first introduced Eugenie to the concept of the crinoline.

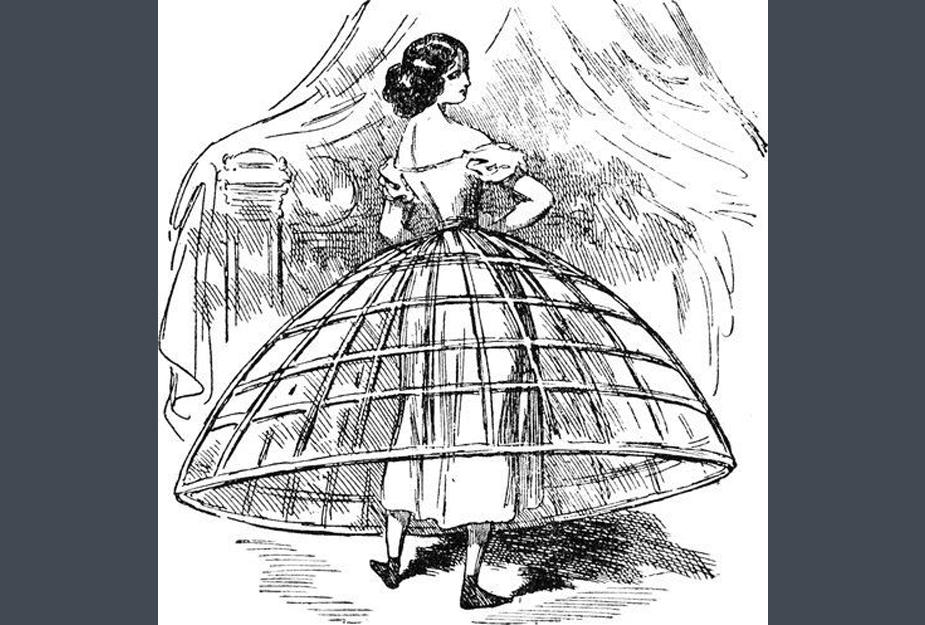

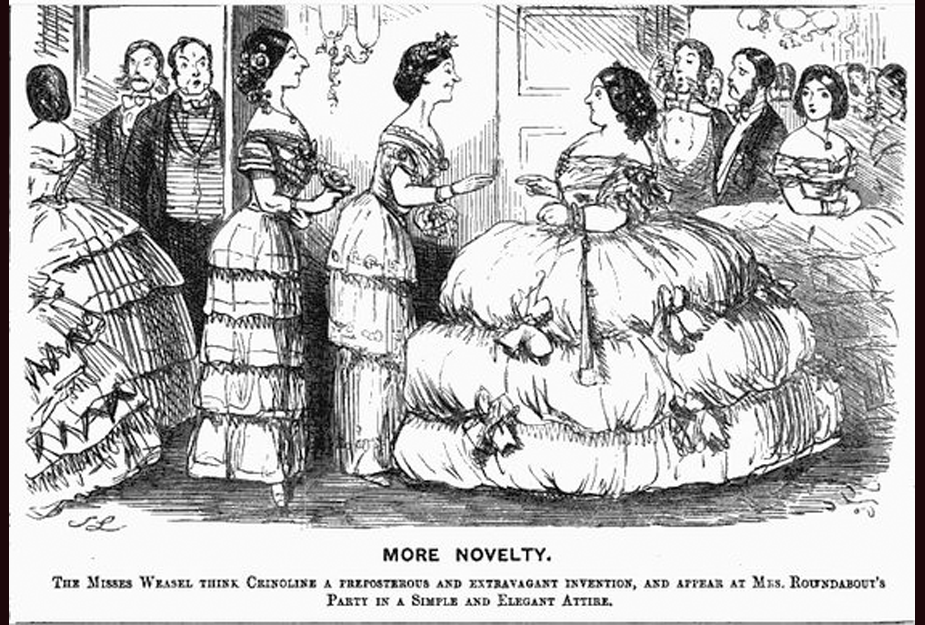

In a sudden and drastic departure from the early 19th century Regency silhouette, Charles Worth’s (Parisian designer setting style trends in the Victorian era) concept of the crinoline took away the multiple layers of heavy petticoats worn by prior decades of women that were used to create the shape of the skirts. Because the skirt was becoming wider and wider from the 1830’s to the 1850’s, when Worth introduced the cage hoop, it was widely embraced.

The crinoline put the entire fashion focus on a tiny waist, which led to the need for tight lacing and corsets that could get not only the look to trick the eye like in the 18th century, but a small waist in reality. Skirt and sleeve dimensions did help with the visual focus, but it was the corset that did the job.

The whole new concept of “Haute Couture” by Parisian Designers from the House of Worth, whom demanded a different “costume” for each activity, demanded a whole new variety of undergarments and corsets too.

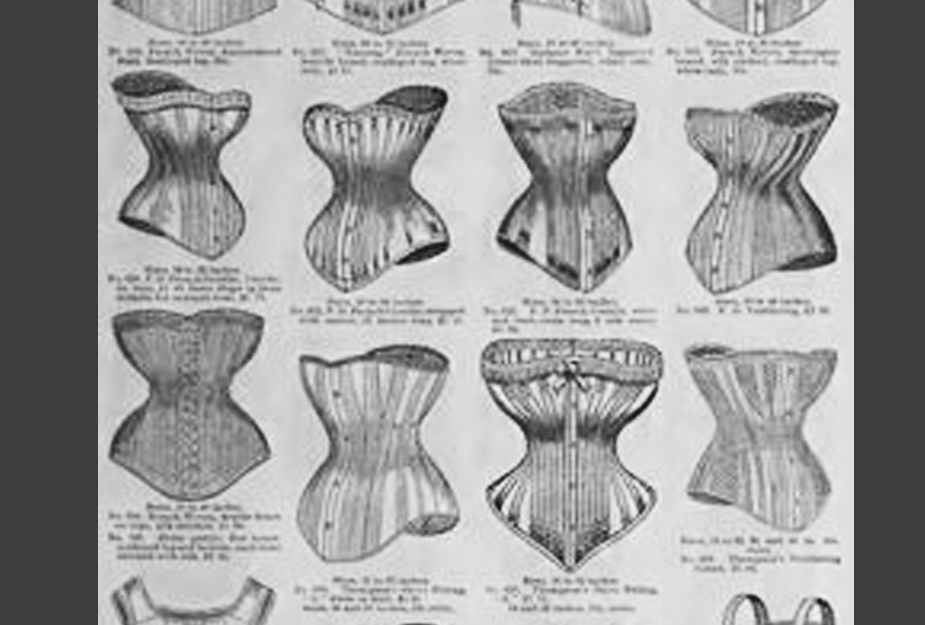

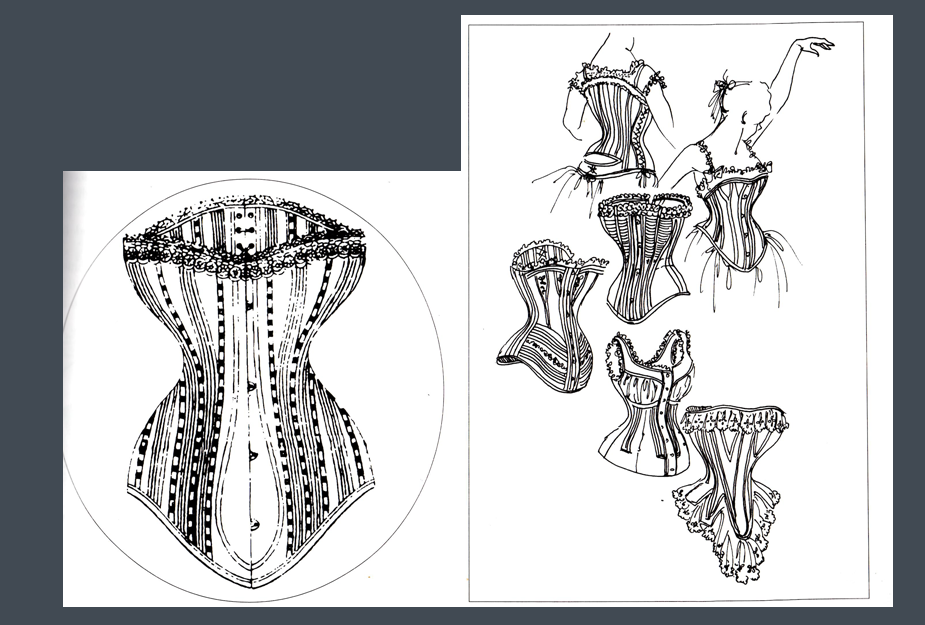

Corset makers by the 1830’s had become masterful artisans, and beautifully decorated corsets came to be built.

Technology changes Victorian Fashion

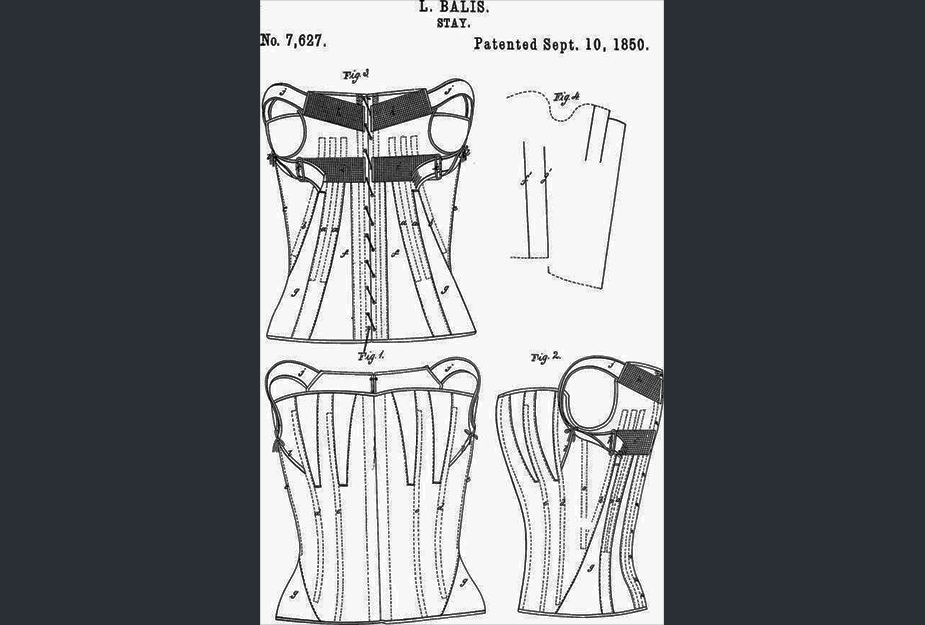

Corsets and Stays were made by hand and hand sewn or hand woven until about the middle of the 19th century. As inventions appeared around the world, corsetry took on more hardware.

The Victorian silhouette began with the reign of Queen Victoria of England when she was crowned in 1837. Of course fashion had been changing and evolving every year, but having a new fashion leader in hand with the French Empress Eugenie, meant American women had an example to follow, and follow they did.

There were 3 technological innovations that caused Regency to become Victorian corsetry:

Invention 1) 1828 metal eyelets perfected for use in garments

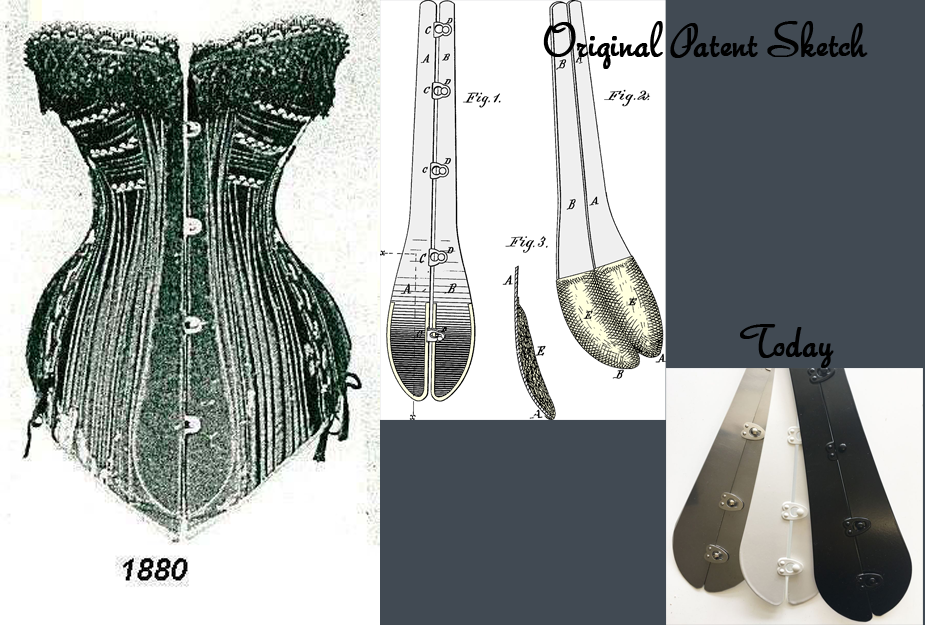

Invention 2) steel front busk of 1829

Invention 3) 1832 Jean Werly from France took a patent on a type of woven corset made on a loom with gussets integrated into the weaving process. These were very comfortable, lightly boned, and very popular until 1889. In 1890, machine made corsets would gain more popularity than the Werly type.

The fashionable silhouette of the 1830’s had huge sleeves, a high waist, and increasingly larger skirt. As the decade progressed, the waistline dropped, and the objective became to have a tiny waist. This concept lasted well until the end of the century.

1840’s & 1850’s

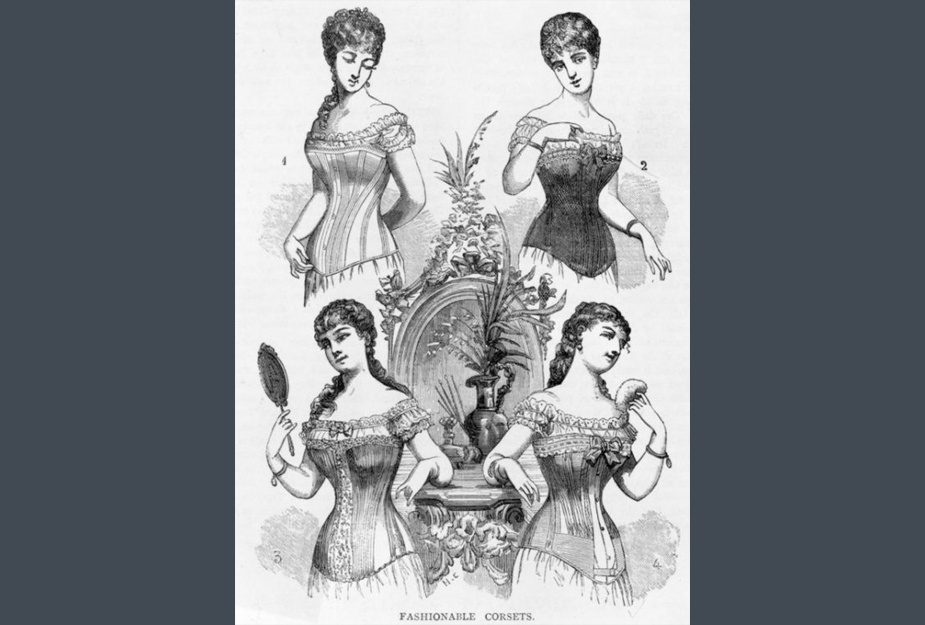

When the exaggerated 1830’s shoulders suddenly disappeared in about 1837 with the rise of Queen Victoria as the fashion icon, the waist itself had to be cinched tighter in order to achieve the same visual effect as having large shoulders. The focus of the fashionable silhouette for corsets of the Victorian era then became the hourglass.

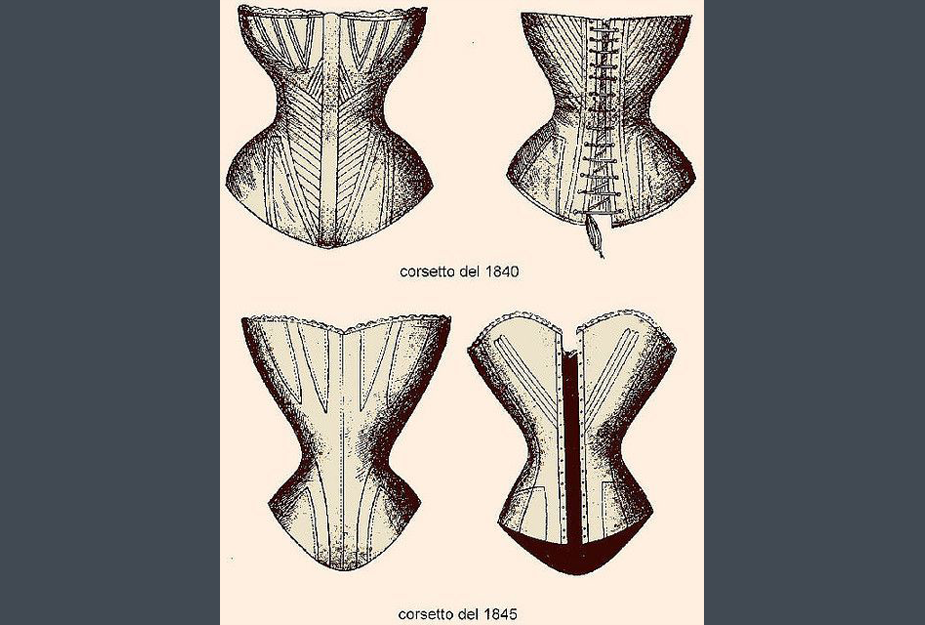

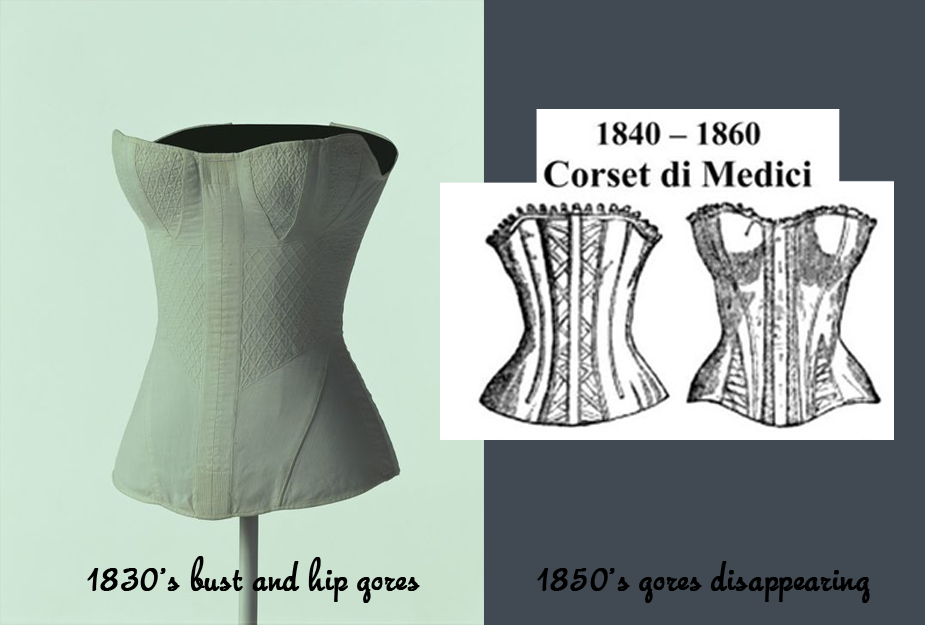

It is in the 1840s and 1850s that tightlacing first became almost universally popular. The corset differed from earlier corsets and stays prior to 1840 in numerous ways.

The 1850’s corset no longer ended at the hips, but flared out and ended several inches below the waist.

The new style of the 1850’s corset was exaggeratedly curvaceous rather than funnel-shaped like the late 18th century and Regency styles had been.

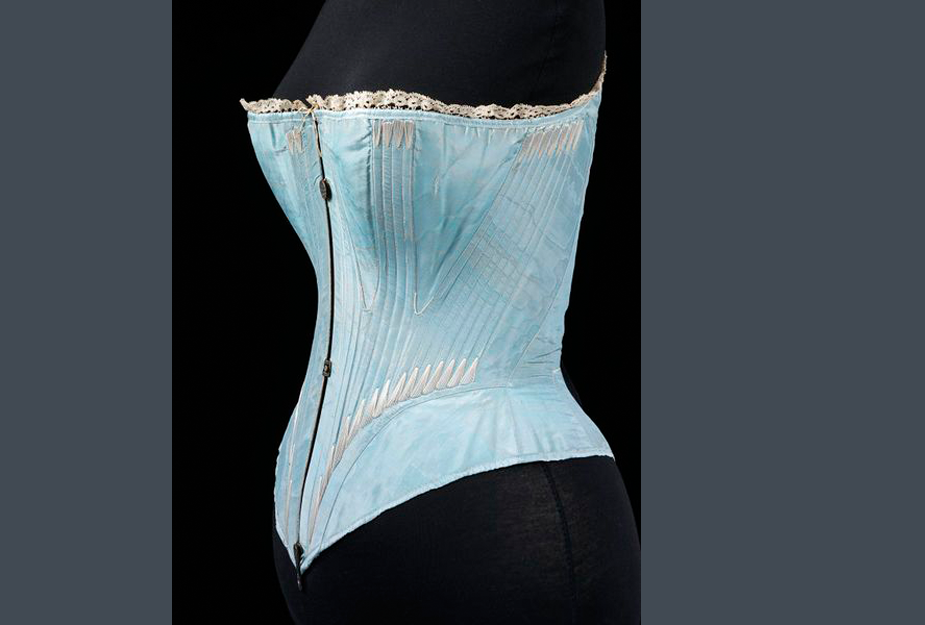

By the mid-1850’s, spiral steel boning stays curved with the figure rather than tricked the eye as the earlier stays, or followed the natural shape of a woman’s body.

The 1850’s began the actual re-shaping the body using the corset.

While many corsets were still sewn by hand to the wearer’s measurements in the 1840’s and 1850’s, there was also a thriving market in cheaper mass-produced corsets.

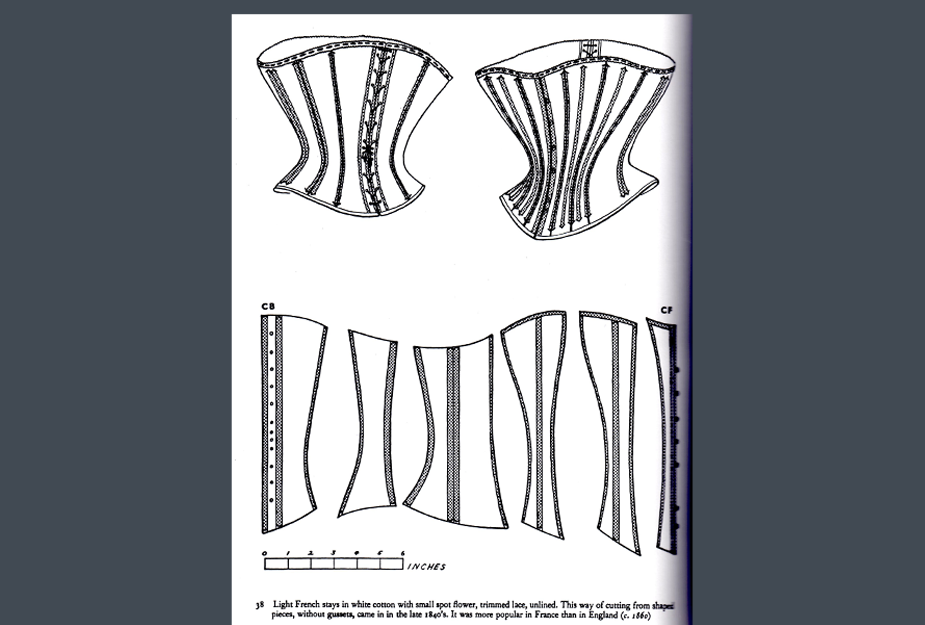

In the late 1840’s in France, where lighter-weight corsets were preferred, a new cut was introduced: the corset without gussets as had been the style through most of the Regency and pre-Victorian eras.

Queen Victoria took the throne in 1837, and played a part in popularizing and making available a new silhouette using the new design of the mid-century now Victorian Corset.

The new 1840’s Victorian corset was made from 7-13 pieces, each one being shaped to the waist.

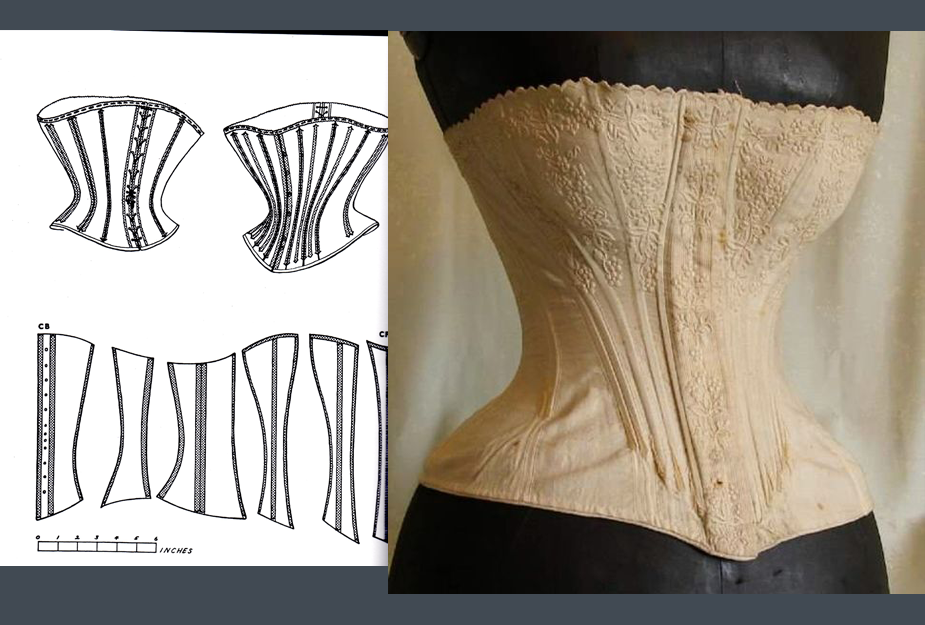

1860’s

By the 1860’s, the waist was the focus, so this “waisted corset” was ideal to force the waist into a small shape. It was an extremely short corset.

The new 1860’s short corset with tiny waist and strong cinching, was popular in the US and France, while England wore the older, longer and gored shapes still.

The mid-century 1850 and 1860 corsets were actually fairly lightly boned, but had added techniques of cording and quilting, have somewhat the appearance of the previous Regency corsets.

The 1850-1860 corset had position of the bones worked with the front metal busk along with back bones to bring in the waist.

Because the crinoline was huge below, the bottom of the 1850-1860 corset was of little concern, so there was a wide variety in fit, shaping, boning, and seaming into the 1860’s as the crinoline grew in popularity.

In the 1860’s, white corsets were considered ladylike, although gray, putty, red, and black were worn more often as they were economical.

Most corsets were made of 100% cotton coutil and ALWAYS lined in white cotton. Coutil was a special, very densely woven fabric that had little to no stretch in any direction. It is still the preferred fabric for today’s corset construction and is very expensive in the US has there are few sources for it. Companies in Canada and the UK still produce cotton coutil, while many of the synthetic blends come from China or other Asian countries.

Shaping the Body

1870’s

From about 1875-1900, Europe would again be at war (in South Africa), so military uniforms would again affect women’s fashion. The long, well fitted and superbly tailored woolen tunic with gold trim guided fashion houses to build women’s costumes based on these types of garments.

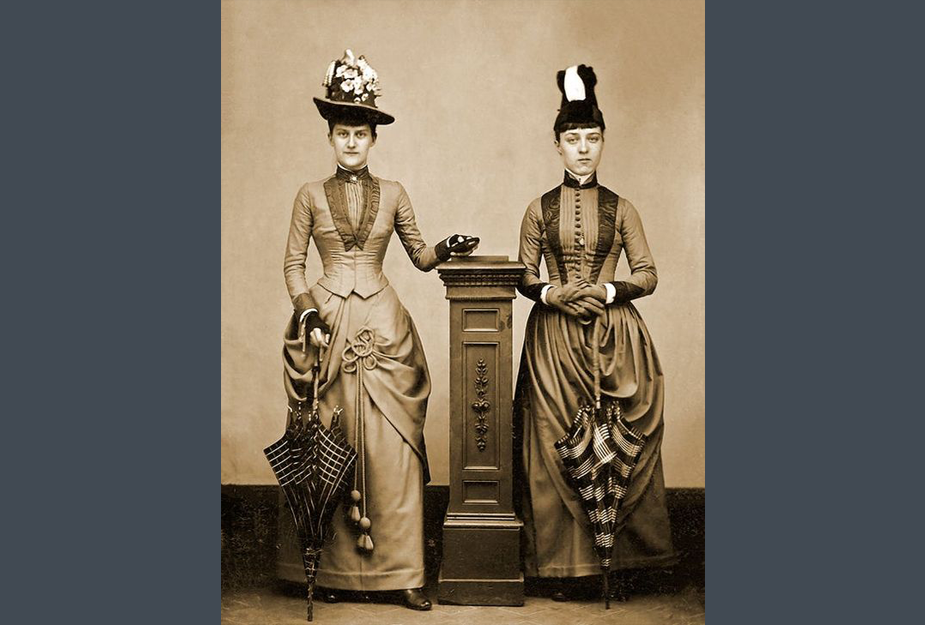

In the 1870’s, the demand for military uniforms led to development of mass production techniques which focused on uniformity. Women, previously hating to look like anyone else, embraced the new armoured “cuirasse” look like they were a part of a military regiment more and more as the century progressed.

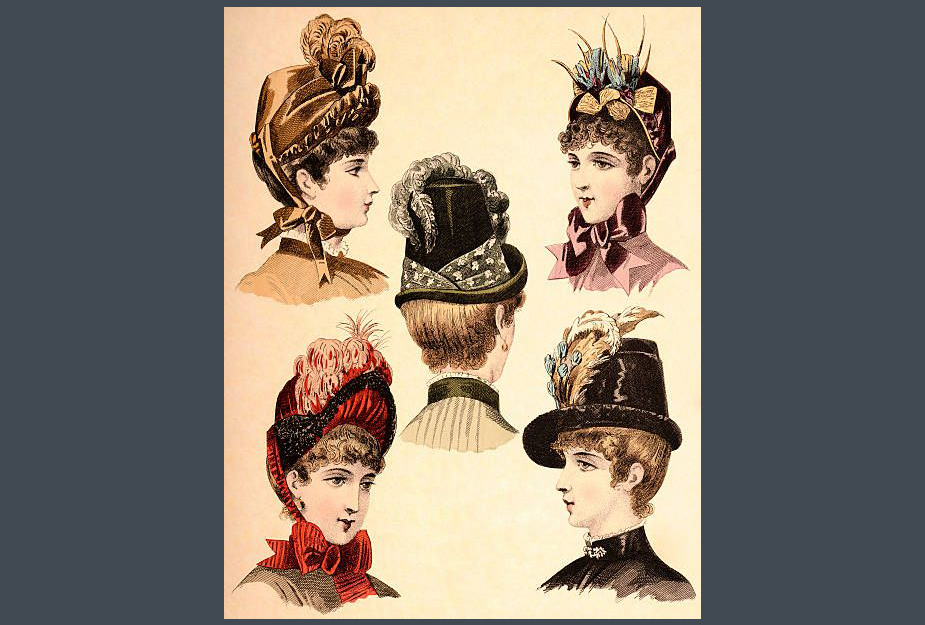

The “Prussian” collar became a staple in the 1870’s. This was the characteristic stiff necked style that continued until and marked the end of the 19th century and the Victorian era.

The “mannish” Prussian collar in the 1870’s lent a “Hauteur” to women’s dress, which led to special blouses and shirts which required special training to get them on and off, and to prevent the neck from being crushed.

In the mid to late 1870’s, girls wore corks around their necks with needles sticking out to train them to hold their heads high and straight while wearing collars so the collars would not bend or roll.

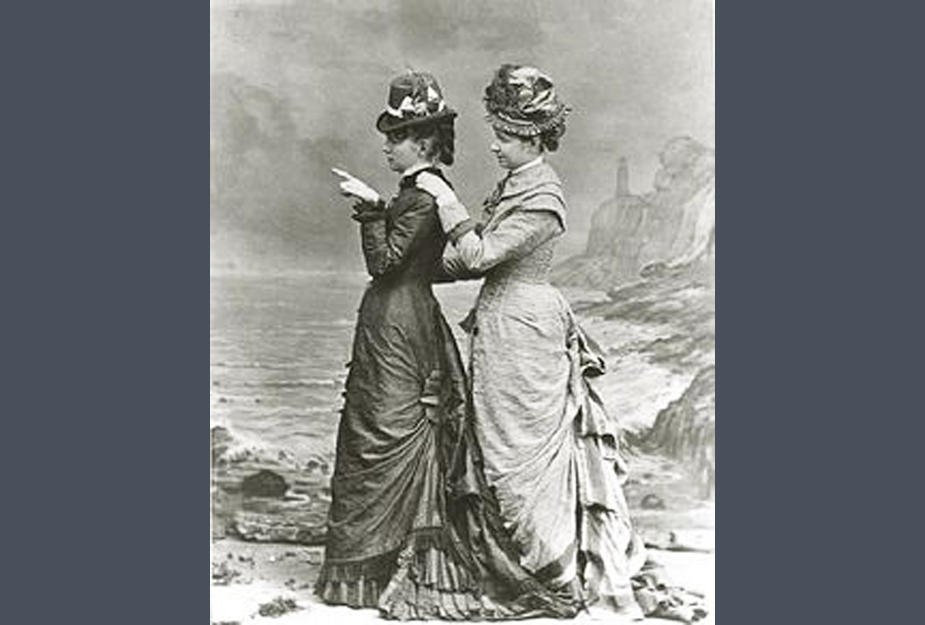

When in the mid 1870’s the crinoline with its silhouette of the teeny waist and huge skirts was replaced by the first bustles or “tournures” (“turning bustles” – softer versions of full padding over the rear end) and the ideal silhouette became a long, molded sensually curvaceous figure down the legs and hips.

Much fuss was made about the bustle by cartoonists and serious fashion experts as it was a very notable feature of fashion. The real fashion statement defining the mid 1870’s though was the amount of trim, ornament, and “things” piled on top of “monuments known as bonnets” according to a fashion magazine of the time.

The skirt of the early 1870’s was straight in front although not fitted, and flared towards the back. A bodice had a peplum or little skirt in back to emphasize the shape.

By 1871 the draped skirt that was being worn in the back, moved to the front of the skirt like an apron. The “polonaisse” drape was invented and worn over increasingly tighter and more fitted skirts.

In 1874, the front was more fitted and the back became elongated into a large curve.

By 1879 though, the skirts had slimmed down into a vertical shape, and were fitted all along the body and over the hips. Dresses were two parts; skirt and bodice, and the bodices elongated with the skirt.

Through the middle of the 1870’s, the bustle continued to grow larger and had more pads that had strings and ruffles.

As 1876 progressed, metal and wire contraptions replaced the pads.

Suddenly, in about 1878, the bustles were discarded for a time.

Through all the changes in back padding, bustles, and draping over the rear end in the 1870’s however, the focus of fashion, and the visual silhouette remained pinpointed on the waist.

The 1860’s shorter cinching corset remained in style until about 1875 when it elongated and focused on pulling in the tummy since the front of the skirts were become flatter and more conforming to the stomach and hips.

Some women still wore the shorter 1860’s style until well into the early 1880’s for sport, work, or rural situations where function exceeded the desire to be fashionable. One could bend and sit in the 1860’s corset, but not so with the new end of 1870’s long conforming style.

By the end of the 1870’s, the corset was at its greatest function it had ever been and would ever be, as it now took on the role of shaping the body from top to bottom. Previous versions focused only on the waist, or bust, or in shaping and slimming. This new one was intent on forming the body.

Every woman had to wear a corset in the 1870s and 1880s, and it was nearly impossible to get the shape out of a homemade corset. This meant they had to buy them ready or hand made from someone who specialized in these new, specific, and conforming corsets.

In the 1880’s, the corset industry was at its peak production and profitability in history, and corset companies in America and Europe flourished.

1880’s

At the same time demand grew, ladies’ magazines started to give more details and illustrations of the specific details of dress and undergarments. Advertisements for mass produced corsets, previously very rare, became abundant.

From the attention to detail in the shaping of the dress and body of the late 1870’s and early 1880’s came great variety and demands for more inventions and contrivances in corsetry.

The new “cuirasse” body of the late 1870’s and early 1880’s enveloped the hips, waist, and upper torso.

In the 1880’s, since women were so very different in shape and size (and we might add “squishiness”, the great difficulty became how to keep the long armorlike look on every woman without the corset riding up and wrinkling, and the bones from breaking at the hips (which happened often going from extremely full hip and bust to a very tiny waist region).

Various methods of boning were tested, and steel became used more and more.

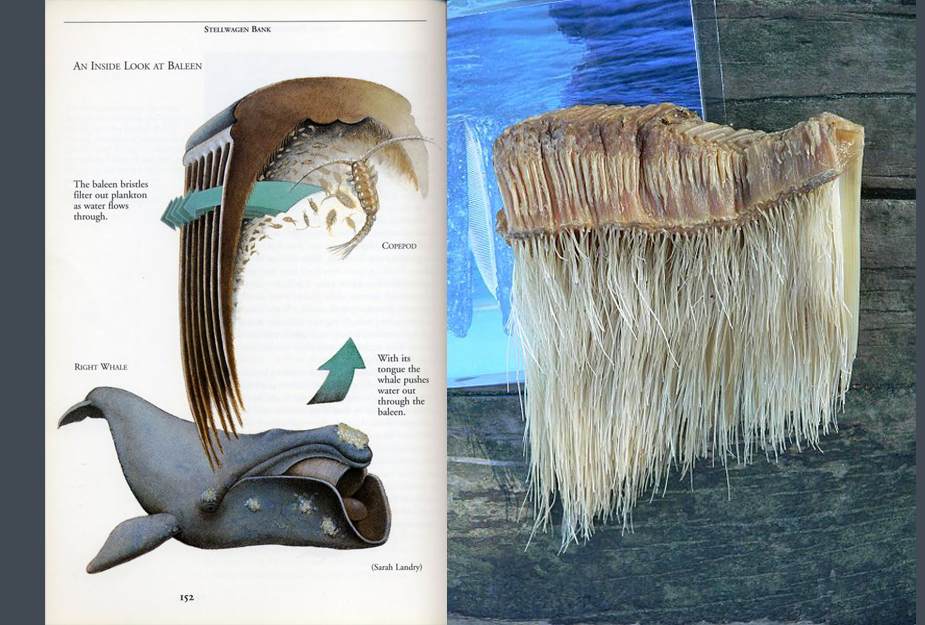

By the early 1880’s, whalebone was in such high demand that it became scarce and very expensive, so substitutes such as cane were used for boning (stiffening) corsets.

Prior to the 1880’s, whalebone was used almost exclusively for boning in corsets. Whalebone is actually whale baleen, the cartiledge from a whale’s mouth. It was basically stiff, but had enough flexibility or elasticity to work well with curves. Unlike modern plastics which have been used to replace it today, whalebone would not re-shape with body heat or vary with air temperature.

In the 1880’s, two main styles of corset construction continued the same as in the mid-19th century: either with gussets and a basque, or in separate shaped pieces (like in the 1860’s).

In 1873, the invention of a spoon shaped busk that looked somewhat like a soup ladel (“busk en poire”) had been invented, and was a key innovation to keeping the tummy tucked in, and handling the torque between top and bottom until about 1889 when the next style of corset would take over.

Today’s spoon busks are very strong and very expensive, but they still do the same job of tucking in the tummy to make a lovely flat front of the skirt.

The spoon busk allowed extremely restrictive and tightly cinching corsets to be made. One model of the early 1880’s had 20 shaped pieces and 16 whalebones on each, as well as the spoon busk.