The Hidden Art of Healing

The Hidden Art of Healing

Nursing is the art of nurturing, supporting, and empowering fellow human beings. It’s practitioners are devoted to the well being of others. There were times when “carers” were valued, and others when they were vilified, undermined, and persecuted.

Ancient societies had Shamans with knowledge of the healing properties of plants, minerals, and crystals. They were respected and feared; considered “nurses”, but the concept of “nursing” was established much later among women of societies who just extended the role of caregivers rather than any defined position.

Early Egyptians and Babylonians only had records of healers and methods for the elite they treated, and much of their practice was attributed to magical powers. They did healing in places considered sacred and mystical. In these “sanctuaries” they did things with drugs that induced trancelike sleep to induce healing.

The Greeks related healing to the Gods and also had places with magical powers where people went for treatment and recovery. It was the Romans though who first recorded the subject of nursing as distinct from other arts.

Christianity Records & Defines a Profession

The Roman’s Christianity had emphasis on self-sacrifice which meant putting oneself above worldly goods to help others. Those who aided the sick were obtaining their own “salvation”; a reward in heaven.

The Christian concept of “loving one another” brought nurses to fields of war even as Christians fought in contradiction to that same tenant. During the time of the Roman Empire, nursing became an heroic pursuit.

From 0-400 AD, groups of fashionable and elite women embraced the charitable work of the Christian Church. These “deaconesses” (translates to “ministers”) assisted with baptisms and visits to the poor and sick. They became experts in healing, and many were sainted.

Dark & Medieval

After the fall of the Roman Empire and its religious basis, civilizations around the world and particularly in that region struggled to rebuild. Very few records survived to keep history of the healing arts, or any pursuits for that matter. The time was considered “in the dark”.

Most of what is known of the time was recorded by members of religious orders who also established hospitals. They had the only preserved knowledge of caring for the sick and elderly, since previously skills and knowledge were handed down from one person to another and not documented.

By the Middle Ages, civilizations were recovering, and Medieval Europe saw two movements: women healers in rural societies, and “nurses” of religious orders. Under the Catholic Church and its emphasis on “spiritual healing”, the Shamans and “witchcraft” type of healers disappeared as women voluntarily took on the role of healer as a natural extension of their daily duties in caring for family.

These care providers had no formal education, and were viewed with suspicion because their methods were mostly herbal, and because they didn’t work in rituals or spiritualism. They handed down their knowledge from one “wise woman” to another, and had to teach each other in secret.

From Sinner to Saint

Members of a great monastic movement in Europe had cloistered themselves away from society. They took vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience to God, and shared the wisdom of healing and taught each other. Within the walls of their convents, they established hospitals. The women were called “nuns”.

There also arose at the time a secular (non-religion based) type of healer called a “tertiary”. These were church laywomen who devoted their lives to good works. Nursing became associated with these women who dedicated their whole lives to caring for others, and the attainment of “saintliness”. This often put them in danger as they worked on the battlefield and with epidemics.

Crusades & Battlefields

During the 11th, 12th, and 13th centuries the image of the Saintly Nurse had developed, but now men were creating “brotherhoods” for those in healing roles. They accepted women, but remained completely segregated from them at all times.

These were military nursing orders which upheld medieval ideals of chivalry, heroism, and charity. They became wealthy from donations from noble and royal families that they helped, and used the funds to build huge hospitals in the Holy Land where battles were taking place, and along routes between Europe and the Middle East.

Rise of the Physician; Downfall of the Nurse

In the 15th century nursing knowledge continued to be passed along orally and practiced with “hands on”. Women healers took on apprentices who were educated in religious houses. Some the training started to be written down.

The rural healers now became highly regarded and respected due to accumulated knowledge. The practice of medicine became an elite pursuit and was taught in universities which included men and women (still segregated).

These early “physicians” kept a distance from the people they treated in order to protect themselves from the plagues and ills. By the 16th and 17th centuries, physicians only touched people wearing protective masks, gloves, and protective herbs. Many wore giant masks with “beaks”, and other contraptions.

It was only the local women who continued with “hands on” healing. Unfortunately, with the value placed on physicians set apart from the people, those women who worked face to face with the sick found themselves accused of witchcraft because people thought the “nurses” practiced the dark arts in order to keep themselves from getting the sicknesses they were in contact with.

And Rise Again

Women of both high and low classes, however, continued to be the most knowledgable about herbal medicine, sanitation, and general health care. These were left to the woman in charge of a household, although servants implemented the woman’s directives. The nursing profession, apart and separate from the new industry of medical training for physicians, continued to be passed by word of mouth and somewhat in secret. The information was often spotty and unreliable.

Protestant Reformists in the 16th century outlawed Catholicism in many states of Europe, and the monastic based hospitals of the previous eras were abandoned – losing all attempts at organized healthcare. States remaining Catholic underwent changes that redirected healing to being part of “good works” again, and so nursing orders and “nuns” re-emerged as an organized healing group.

Nursing was now seen as a “caring art” form, where the aim was to make the patient “whole” physically, emotionally, and spiritually. Religious orders continued into the early 19th century as the only organized and experienced nursing care.

The New World of America

The “Grey Nuns” were one of the first known nursing groups to go to the New World. They were led by a French woman to “New France” which is today’s Quebec in 1641. The first known hospital on the continent was inside the fort at Ville Marie, where those wounded from skirmishes with the native Iroquois were treated.

The Pilgrims who founded some of the first European settlements in the United States took men an dwomen with them who were known to care for the sick. The first Pilgrims were believed to have taken a Dutch deaconness-nurse.

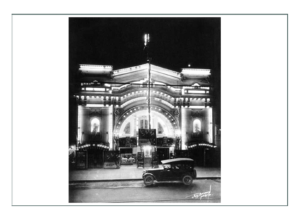

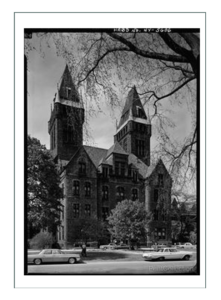

One of the earliest hospitals in American was founded in New York City by the successors of these healers. It was linked to the “poorhouse” and believed to be the predecessor of today’s Bellevue Hospital. The first city hospital was the “Charity” in New Orleans.

In the 18th century and early 19th centuries, many American hospitals like their European counterparts, were connected to poorhouses. They were badly funded, and nurses were often untrained paupers themselves.

“Early Modern Period”

Years 1450 to 1800 are called the “Early Modern Period”. As the Middle Ages became the Early Modern period, nursing knowledge continued to be learned as part of oral traditoin. Nursing was done and learned directly hands. on. Women healers passed on their wisdom and expertise by taking on young apprentices.

As reading and writing became more common and widespread starting with religious institutions and later for most of society, people started to be able to write down remedies, methods, and techniques for caring for the sick. The problem was even with the newly recorded information, only someone working with an experienced healer could truly learn what to do.

In rural areas healers were respected. At this time the study and education of medicine was made only at elite institutions by individuals who intentionally stayed as far away from actual patients as possible. When plagues hit Europe in the 16th and 17th centuries, some educated physicians actually visited patients, but kept themselves hidden behind beak-shaped contraptions full of herbs.

It was local “handywomen” or members of religious orders who actually practiced hands on healing with seriously ill or dieing patients. These women healers, however, were in danger in the 16th and 17th centuries from both Catholic and Protestant churches who went on hunts for people they thought had made pacts with the devil – witches.

Healers who could actually cure people through their wisdom and practices were considered to have unnatural powers, so the religious paranoia had them “damned if they do; damned if they don’t”.

Medical care, therefore, at least in rural areas, was done by the “wise women”, or the female head of the house, although often servants were assigned the role of healing. While knowledge of herbal healing was increasing, it was not passed along nor written down between rural healers.

16th century dissolution of monasteries, the place where healers were located previously outside of the home, pretty much destroyed the practice of healing until almost into the 19th century in Europe. States who decided they would remain Catholic went back to old ideals and philosophies though, which valued “good works”. This meant healing was once again valued.

Nursing became known in these places as a caring art form, with the aim to make the patient “whole”; meaning physically and spiritually. Until the 19th century, almost all organized healing was offered by these religious orders. Members had some education and apprenticeship training from experienced mentors.

Among the new religious orders dedicated to the care of the sick were the Daughters of Charity. It was a movement that emerged in France in the early 17th century, founded by a Catholic priest. Vincent de Paul, working with a noble woman, Louise de Marillac decided to found the sisterhood. Newly widowed, Louise wanted to use her new found freedom to care for the poor, and she and de Paul brought poor countrywomen together into her home and taught them how to give care to the sick.

The education of the women became more sophisticated, and the movement spread so that by the time Louise died in 1660, there were more than 40 houses of training in France.

The Daughters of Charity cared for the sick poor in their own neighborhoods of Paris, and eventually because of their excellence, they were asked to provide the nursing care at the oldest and largest hospital in Paris, the Hotel Dieu. They extended their work from there to giving nursing to hospitals, prisons, orphanages, and other institutions.

The Daughters of Charity dressed in blue-gray nun’s habits, and became known as the “Grey Nuns”, even though they were not directly a religious nursing order. They had more freedom than nuns, but their large white “cornette” headdresses made their profession recognizable.

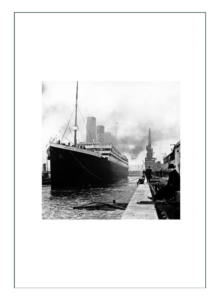

The Age of Exploration

The Early Modern Period is also known as the Age of Exploration. Seafaring nations such as England, France, Spain, and Portugal sent expeditions to points all around the world such as explorers Christopher Columbus and Jean Cabot who navigated the Atlantic Ocean and “discovered” the “New World” of North America. The Spanish and Portugese did the same in Central and South America.

Nurses and healers became a key part of colonizing the new territories, and most traveled through Catholic religious orders with the intent to convert “native” populations to Christianity as they created great hospitals and schools.

The “Grey Nuns” were among the first to arrive in the New World that would become America. In 1640, Jeanne Mance, a trained nurse from l’Hopital de la Charite at Langres, France that was modeled on the Sisters of Charity, was sponsored by a wealthy woman to establish a hospital in what would become Quebec, Canada. The second known hospital on North America was on the island of Montreal in a small hut inside the fort. Jeanne nursed the wounded from skirmishes between the French colonizers and the Iroquois tribe.

The first hospital was founded by the white-robed Augustinian Nursing Sisters from Normandy France in Quebec. These nuns were of a cloistered order with strict vows. They arrived in the middle of an epidemic in 1639. These women were pioneers, diplomats, and worked to resolve rifts between factions. It was the French nursing sisters who resolved not only the many epidemics of the time, but also issues between French, British, Iroquois, and Algonquin.

The American Colonies

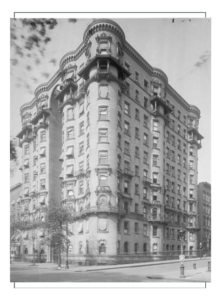

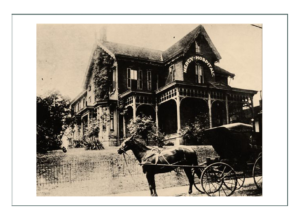

The Pilgrim Fathers took skilled healers with them to the earliest European settlements. The earliest known nurse was a Dutch deaconess from Holland. One of the earliest hospitals in America was founded in 1658 by the West India Company in what would become New York City. This hospital was linked to the poorhouse and was considered the predecessor to the famous Bellevue Hospital.

The “Charity” of New Orleans, run by the Sisters of Charity, was founded in 1720, and became a city hospital in 1811.

In the 18th and early 19th centuries, many American hospitals, like their European counterparts, were connected to the poorhouses. They had no money, and caregivers were untrained paupers who themselves were destitute.

The Philadelphia General was founded as an almshouse in 1730 and was run by pauper inmates. it became a hospital in 1816. The stage was set for establishing permanent institutions and the profession as legitimate as the 19th century progressed. During the 19th century, nrusing would change from an expression of religious piety to a professional discipline. Urbanization was one key factor, as the earliest organized nurses were located in large cities to help people sick from living in urban and industrialized situation.

Click here to return to Susan’s Colonial Healer project

A Real Profession at Last, But not without Perils

During the 19th century, nursing changed from an expression of religious piety to a professional discipline. This transition was shaped by key events and individuals, as nurses took an increasing role in public health care and the fight against disease.

In Catholic countries nursing continued to develop in relation to the monastic orders, but in countries that had adopted the Protestant religion during the 16th century reformation, the Early Modern period was a dark time for nurses. In rural areas women healers were the backbone of care, yet they were viewed as outcasts and persecuted as witches. In these places there were no religious or tertiary orders to document or pass along the skill of nursing, so much knowledge was lost to suspicion and heresay.

The first impetus for reform and acknowledgment of the skills was driven forward by specific individuals such as Elizabeth Fry, Mary Jones, Dorothy Pattison in England. Orders such as the Anglican Sisterhoods in England encouraged women to persist and develop their skills in nursing. These were driven by the desire to help the poor and based on Christian piety.

“Deaconesses” still created the organized centers for nursing, especially in Scandanavia and Germany. Kaiserswerth was the most famous and one of the earliest German deaconess care houses. It was a training center as well as an orphanage.

Meanwhile in America

America was seen in the 19th century as the land of freedom. Europeans wanting to escape poverty and persecuting migrated. There both Catholic and Protestant nursing sisterhoods could be established in the same place. The French movement of the Daughters of Charity inspired a new movement in Maryland in 1809. Later the Kasierswerth would establish a house in Pennsylvania. Sisters of Charity nursed during cholera epidemics in all the major US cities at the time.

Across the US, most still depended on individual and somewhat random caregivers, until the change of culture due to the Industrial Revolution. At that time in reorganization, there became assigned quality and trained nurses hired by communities, including private nurses who worked for specific families or businesses. These were called “born nurses”, who were trained under the instruction of older women, by the family physician, and by hands on practice. They were not formally educated in the art.

Class Disparity in the Profession Same as in the World

Nursing had evolved from its origins as independent nuns and herbal healers by the 19th century to become organized centers to help urbanized society with industrialized strife. Class disparity also divided the profession into “the Lady Nurse” and the “working-class nurse”.

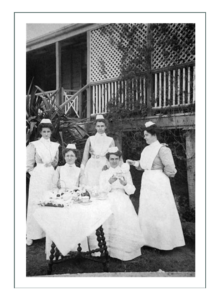

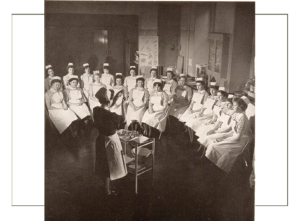

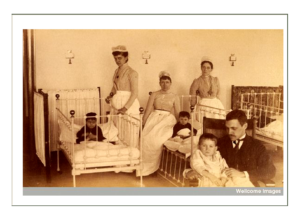

“Ladies” like Florence Nightengale who defined the role of nurses and is credited with establishing the profession as we know it today, were considered heroines and were well known to the public. They presented themselves in starched white dresses and caps that made it difficult to believe they actually touched patients. Lady nurses performed “technical” or “scientific” work such as administering medication or carrying out complex wound dressing.

“Working Nurses” were largely anonymous, and society appeared to heap contempt upon them. They did much of the hard and “dirty” work in hospitals, and their services blended with the work of domestic “Ward Maids”.

After 1860, secular nursing schools proliferated following the example of the Nightingale Training School.

A Very Real Profession with Secrets

Nurses, now with formal education as well as hands on training, were by the end of the 19th century dealing with all matters of mankind. Nurses, in attempt to elevate the profession, kept many secrets of the day to day dealings of their lives. By the 1870’s, despite the class disparity, all nurses actually did “hands on” and “dirty work” of cleaning the bodies and dressing foul wounds.

In attempt to maintain the appearance of “purity” and high status, particularly of the “lady nurse”, little information was passed along about what they were really doing, although their training was now public, wide spread, and organized at the university level and among hospital and care facilities that took pride in the specifics of what they taught.

The intrinsic rewards of the nurse originally created by “self-sacrifice” and “helping others” by the turn into the 20th century was no longer enough. In an increasingly secular society, self-sacrifice lost its romance and nurses looked for a “modern” way to gain support and visibility.

One approach was to embrace new technologies of the medical sciences. The other was to play an heroic role on the battlefield.

Sticks, Stones, & Swords in the Beginning

Nurses and early practitioners of the healing arts had always been at the ready to help with those injured or ill due to war and battles which seemed on going world wide. At the beginning of the 19th century, however, with the fracture of European cultures and conflicts such as the religious split due to Reformation, the passions fueled many small wars constantly.

The American Revolutionary War and then the Napoleonic Wars meant continual conflict somewhere. People were somewhat accustomed to violence, but as the 20th century approached, advanced weapons and technology changed the face of war, and so it changed the way nurses had to work.

Advanced Weaponry

Invention of increasingly destructive weaponry that caused large numbers of casualities meant treating those who fell on the battlefield was not the single man, but thousands at a time. The only medical care was offered by orderlies, men from within the military ranks, or female camp-followers.

Although the latter were considered disreputable (prostitutes), many were the wives and sweethearts of the soldiers who cared for the wounded out of honor and compassion. There was, however, nothing even remotely resembling organized medical care.

Nightengale’s introduction of organized nursing care in the Boer War in the Crimean is of particular note for that it completely changed the concept of medical support for war.

War Nurses in America

Civil War

Like any civil war, Americans War Between the States found people unprepared and disorganized. At first the government sought the help of the Catholic Sisters in Pennsylvania and Illioois, who already ran hospitals and were the most skilled for caring for wounds. There were too few of them, however, so the government enlisted the help of Dorothea Dix who was appointed Superintendant of the Female Nurses for the Army.

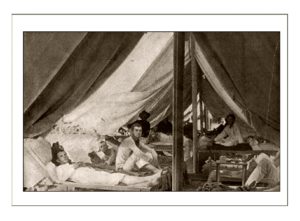

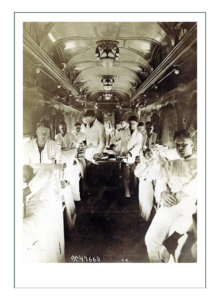

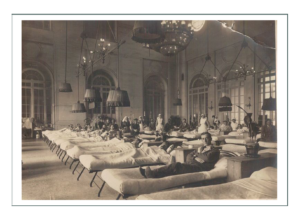

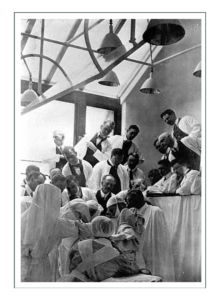

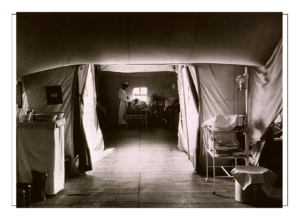

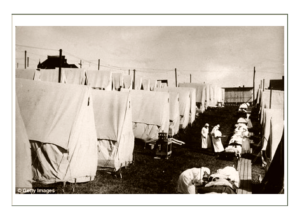

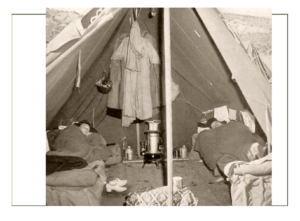

Under Dix, more than 2000 women served as volunteer nurses during the Civil War. Many, such as “Mother Bickerdyke” who attended the wounded at 19 major battles by going through the bodies with a lantern in the night searching for those who may have been missed by the orderlies, gained fame. Temporary hospitals were established in country hosues, tents, and public buildings. Steamers on the Mississippi River were converted to hspitals.

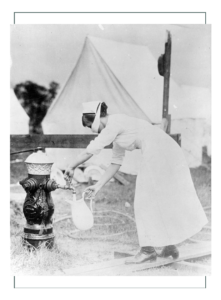

The nurses dressed wounds, gave medicines and diets, and offered care and comfort, yet there were so few and they were so poorly organized that men were often simply laid in shelters at the site of the battles with no care at all. Gangrene was a major cause of death due to lack of supplies and care.

Key nurses like Clara Barton joined troops as they moved, and were at the front of the fighting, often dodging bullets to get to the wounded. Clara was at the Battle of Bull Run where it was documented she cared personally for 3000 men with the assistance of one other nurse, no euipment, and pails of water. She was also at Antietam to assist in surgical operations, administering chloroform.

The Red Cross

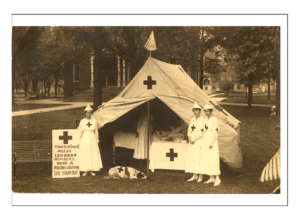

The creation of the International Committee of the Red Cross was due to the efforts of a Swiss activist. In 1859, after visiting battlefields in Italy, he put together a plan by which individual societies would be created in all nations to undertake the work of caring for ALL wounded in wartime. A central committee would coordinate, and a diplomatic agreement was drawn up by 14 nations at what became known as the Geneva Convention; now part of international law.

The Red Cross was to assist those worldwide afflicted by natural disaster as well as warfare. It provided key training for nurses worldwide. In the United States, a division was established by Clara Barten and given official recognition in 1882. The American division provided key support during disasters such as the Michigan forest fires of 1881, Mississippi floods of 1882-3, Texas famine of 1885, and Florida yellow fever epidemic of 1888.

Jane Delano was a key figure in organizing Red Cross and American nursing societies. She developed the American Nurses Association which worked closely with the Red Cross in doing influential work duriing the first World War. Both institutions influenced the direction of military nursing as a distinct specialism.

Into World War I

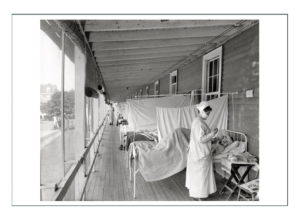

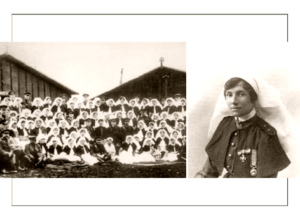

20th century nurses had learned from past wars that more men had died from disease than from energy, so their focus was on public health. The American Army Nurse Corps was established in 1901, and Queen Alexandra of Britain fromed the Imperial Military Nursing Service the next year. These 2 organizations would provide qualified and supervisory staff to all the major wars worldwide in years to come.

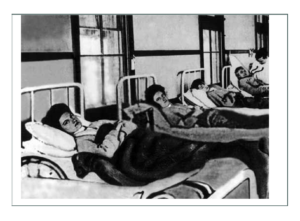

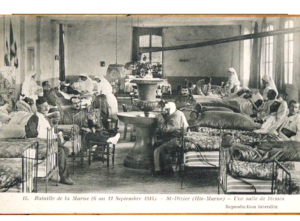

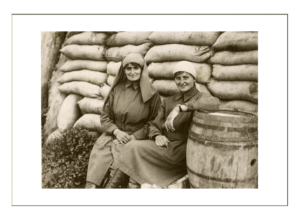

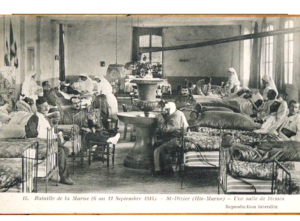

Much of the work of the first World War was done by Voluntary Aid Detachments; women recruited from the US by military hospitals abroad. Most nurses were not prepared for what faced them: mutliating injuries such as lost limbs or parts of faces. To make matters worse, because most battles took place in farm fields that had been spread with manure, horrific infections became the gravest danger, so the job of the WWI nurse was largely to give tetanus shots or apply antiseptics.

The worst horror was the use of toxic chlorine and mustard gases by both sides. These burned the skin and destroyed the lining of the lungs. all the nurses could do was offer comfort.

Ellie’s character, a senior nurse in 1910, would have been called to France 4 years later. Like real nurse Edith Cavell, she might have been moved from one poorly eqiupment infrimary to another, or she might have worked alongside a surgeon.

Captured by the Germans in 1915, Edith summed up the character of the nurse at the time just before her execution:

“..standing before God and Eternity: I realize that patriotism is not enough – I must have no hatred or bitterness towards anyone.”