Key people, events, and technology that caused them to be and to change

See Colonial 1740-1780 and Regency 1780-1837 Era pages (as well as specific projects by date) for more on what preceded the Victorian Fashion Era

See Colonial 1740-1780 and Regency 1780-1837 Era pages (as well as specific projects by date) for more on what preceded the Victorian Fashion Era

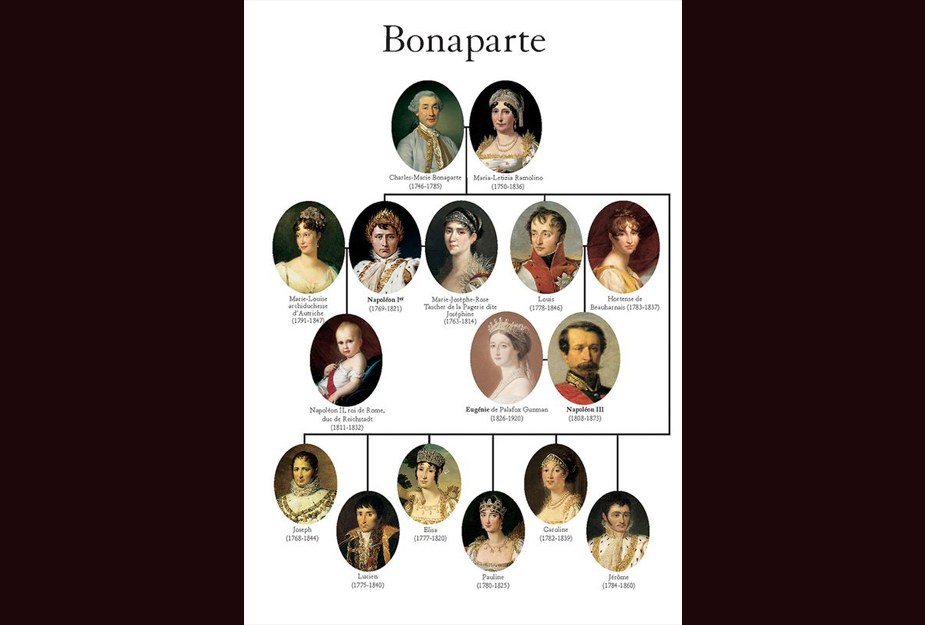

You need to know French nobility.. .. to understand fashion from the 1770’s to the 1870’s. FRANCE led American & English fashion despite the eras being named for the ENGLISH: “Georgian” (after 3 English kings named George), “Regency” (referring to the transition of power between 2 of the English Georges), & “Victorian” (almost a century of Queen Victoria’s dictates).

Only “Edwardian” fashion would actually be spearheaded by King Edward of England.

(photo: Napoleon Bonaparte, Emperor of France’s, direct lineage chart)

Why do we care about French & American Revolutionaries..? The French Revolution was important to fashion, because what France did; everyone else did (include war, conflict, & Court intrigue).

France ruled American fashion from the early 1700’s & through both Revolutions until France’s reign ended with the flashy “Belle Epoque” era at World War I.

France ruled fashion because:

1) England followed France, & America followed England;

2) Trade & communication with other parts of the world was limited; e.g. Japan was an isolationist country until the end of the Shogun era;

3) France made great fabrics, laces, notions, & designs

4) The French, uninhibited compared to everyone else of Western society, went naked in public

(painting: French painter Delacroix’s Romantic Era depiction of the French Revolution)

The French Royals from 1740 and are up to 1840, when, by the time of Napoleon 1’st’s grandchildren, they had cross-populated into all other countries of the European continent: Russia, Prussia, Spain, Portugal, Sweden, Denmark, Bavaria, Austoria, and others (names and boundaries having changed through history).

With a vague wave of the hand to the fashions they introduced, we continue with the Napoleon line as it crosses most “seriously” into the English and Russians, which takes us to 1914 and WWI (the extent of the fashions we build).

If you have studied the Regency Section, you should have your Maries, Josephines, Eugenies, Alexandras, and Victorias of several generations straightened out.

What has this to do with American fashion 1740-1914 you ask??

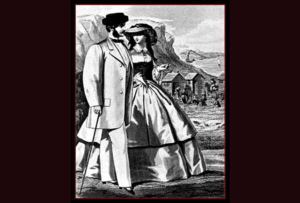

Everything, because until about 1900, America women followed most everything the French (English, Russian, Spanish, etc.) Royals and nobility did, as modified by their own situation or environment.

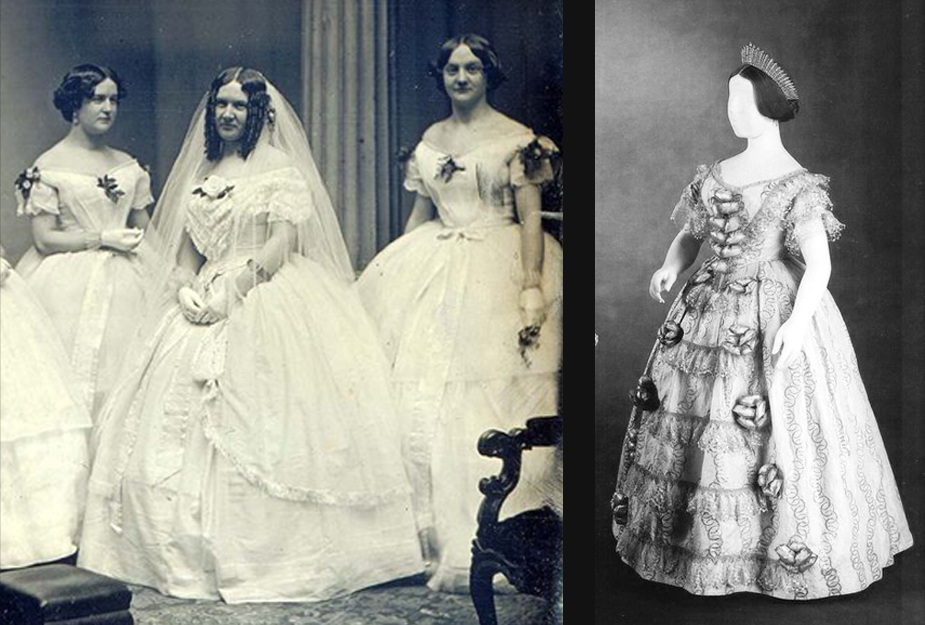

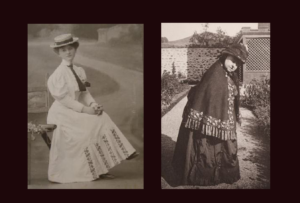

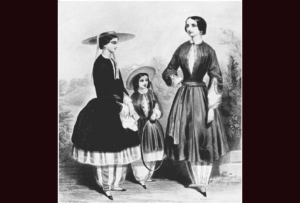

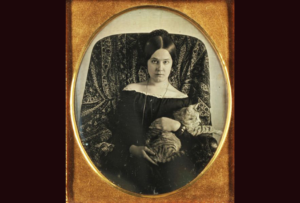

(Photos: 1851 left: American bride following Queen Victoria’s fashion dictates of wearing white for weddings; right: Queen Victoria of England’s 1851 ballgown)

It’s easy to get confused about who the Napoleon family was. There were several Napoleons, and several Eugenies. All were part of the same family. The way to tell the difference is by what they were wearing: e.g. the first Empress Eugenie was rather flamboyant. She wore huge crinolines early, and later the big bustles. She was the height of fashion.

Younger Victoria Eugenie of Spain was the height of fashion, but “La Belle Epoque” extremely sophisticated styles more consistent of what we see royalty wear today.

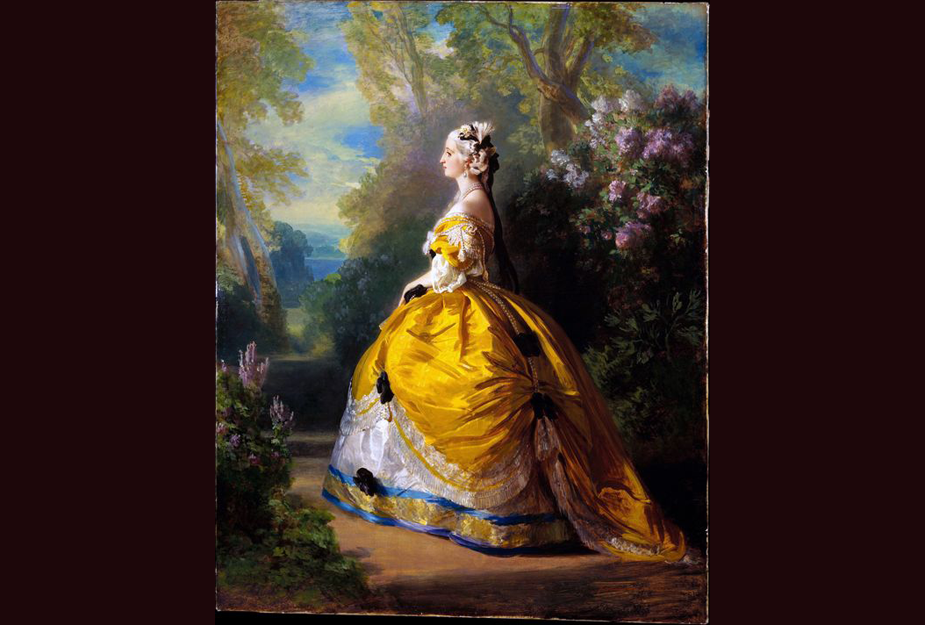

(Portrait: Eugenie of France in an 1854 crinoline)

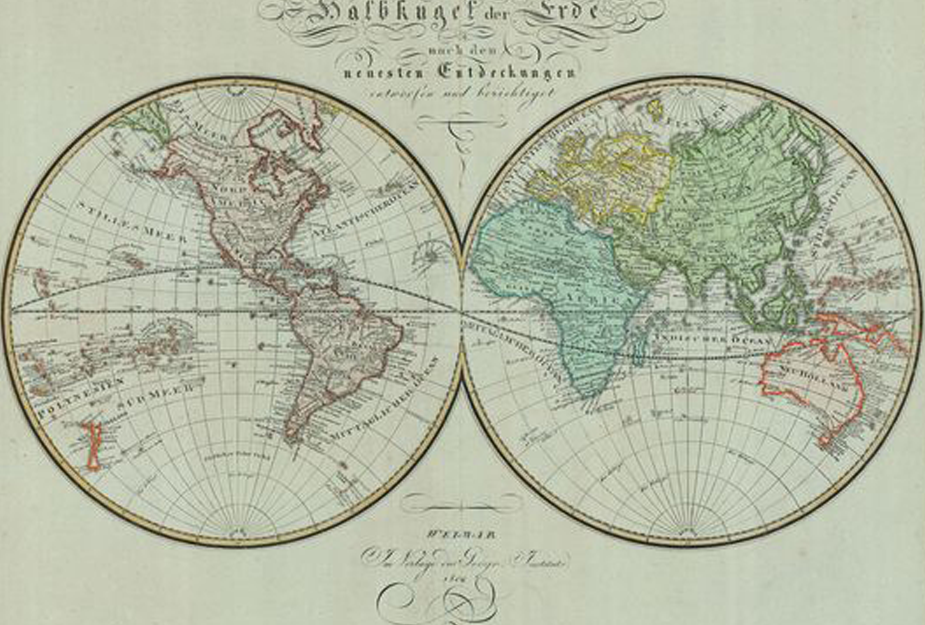

In the early 1800’s, the new United States had been a colony of England. The West Indies were part of England. India, and many African countries were part of England. Prussia, Russia, the Ottoman Empire, and many European countries were at war with each other; changing boundaries and political “ownership”. Asia was, by their own choice, cut off from everyone – denying access, information, and trade to but a few Europeans until the mid to late 1800’s.

Napoleon Bonaparte and France was seeking world domination – wanting to take over England and all their holdings and their world Empire status. This was done politically, militarily, and by populating leadership with the Napoleon family, as we have been studying.

The United States, tied to and limited by England in its ‘infancy’, had won freedom to explore and expand with anyone it chose by 1804. It chose to get into the fray a bit.. grappling for a island countries and those off its own coast to secure its newly won borders.. plus trying to obtain and maintain the vast territories of North America to expand.

Lewis & Clark in 1804-06, allowed the US to understand its potential. Until then, other than trade with the mother country England and her allies, Americans were dependent on what they could produce themselves – meaning ideas and products.

Since English fashion followed French fashion, that meant American fashion followed French fashion too – with modifications for accessibility and availability.

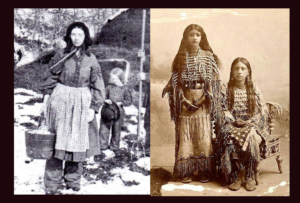

While the world stage changed constantly through the period, the main fashion influence in America (and we have intentionally left out indigenous peoples) was 1740 to about 1840 the French Bourbon kings, English king Georges.. into the Napoleons and their wars, and then the introduction of associated countries of Spain, Greece, Italy, Russia, Scotland, alongside holdings such as the West Indies and north and south Africa with India.

This is especially noted in Regency styles worldwide, as distinct design elements of these countries were added to the French “little white dress” (discussed in the very beginning of this blog).

In the century to follow, there would be tremendous input from the entire world as England regained dominance, European boundaries were redefined and “settled” to some extent, the Asias were opened to European and American exploration, and most importantly – communication and transportation developed to the point persons around the world could share ideas and goods.

First Key Influence – Eugenie of France

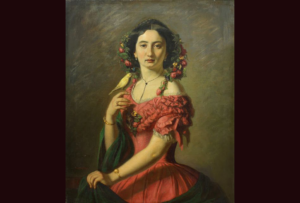

Enter key fashion & historical figure, Eugenie of Spain… … who married Napoleon III (Charles Louis), the nephew and heir to the French throne – or the French Republic depending on the political situation through their married lives.

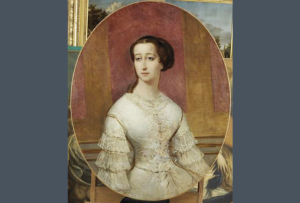

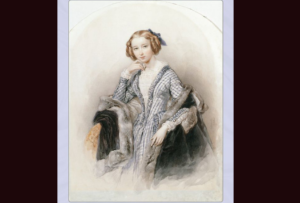

(Portrait: a young Eugenie in the early 1840’s. Note the wide Bertha collar and fitting waist typical of the early Victorian era.. Victoria we will discuss later…)

… although he was only Napoleon’s nephew, he became heir to the throne because Napoleon II, Napoleon’s only legal son born within wedlock to his second wife, Marie Louise, had died as a young man.

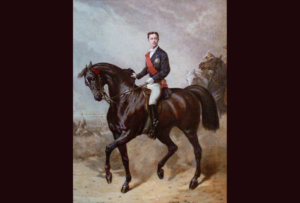

(Portrait: His Prince Imperial Napoleon III as a young man)

Eugenie Montijo of Spain, was educated in Paris… … and got into a lot of trouble. History alleges that because of a young man who spurned her for another, she tried to commit suicide. She was thrown out of school for various behaviors. Eugenie was always very fashionable, and had money to buy the finest.

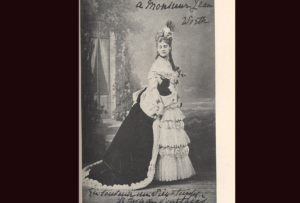

(Portrait: Eugenie in her favorite purple, wearing designer gown with crinoline, making the Worth name famous in fashion)

The marriage of Charles and Eugenie was not happy though… Charles had many extra marital affairs, so Eugenie buried herself in her work, playing the role of Empress well, becoming an extreme influence on French arts and fashion, & therefore world fashion.

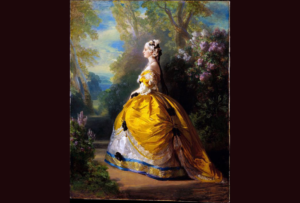

(The most famous portrait: of Eugenie in 1855 shows a young in a Charles Worth designer gown with hoops and crinoline, surrounded in the French gardens by her Court at the height of her fashion influence)

Eugenie’s marriage proposal lives as one of the worlds’ greatest quotes… Spanish born, Eugenie was educated in Paris, & was from the beginning a part of the fashionable aristocratic society. She met Louis Bonaparte (Napoleon I brother) at a party, where he tired to seduce her by asking “What is the way to your heart?”, to which she responded, “through the Chapel, sir”. Their marriage was arranged somewhat as a political alliance.

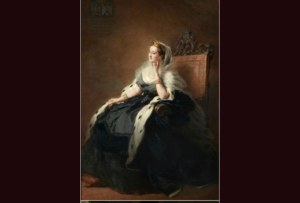

(Portrait: Eugenie’s coronation ensemble in 1853. Always the height of fashion and willing to spend the money for trim)

Eugenie would become the First Lady of France through the 1850’s… … and her influence in fashion and the arts went well into the 1880’s.

Married to Napoleon III, Eugenie was first an Empress, then the wife of a President as his role changed with the political landscape of France.

There were a few Borbons of the ancient French bloodline who would return during her reign, but Eugenie is notable because she was a woman following the footsteps of Marie Antoinette & Josephine.

(photos: Eugenie at her height of popularity in 1855 wearing a designer Charles Worth gown)

Napoleon III with Eugenie ruled as Emperor from 1852-1870… … as France was again an Empire. During this time Napoleon built an estate for Eugenie, who was very unhappy in marriage and wanting to contribute to the arts and sciences. Her “Barritz” drew the most fashionable society to France once again.

(Photo: Chateau de Pierrefronds.. residence and center for arts and sciences)

Eugenie and Charles-Louis were married in a political liason… … Charles (Napoleon III) was NOT the emperor when he married, because the defeat of Napoleon I dissolved the empire. Napoleon III was the President of the 2nd French Republic at the time of his marriage. Eugenie and Napoleon III were married in 1853, and they really didn’t like each other. He had been looking for a wife for political reasons, and she had been groomed all her life for a position of nobility. Both saw the chance to achieve their goals, and agreed to some attraction that made it a bit more tolerable.

(Portrait: Eugenie in 1855 watches her husband receive an award)

Eugenie & Charles tried to have an heir.. .. but they had problems not only with their relationship, but in conceiving a child. Eugenie had 2 miscarriages early in their marriage; one of which history accuses her of having from an extramarital affair.

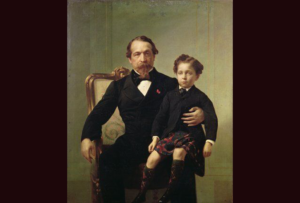

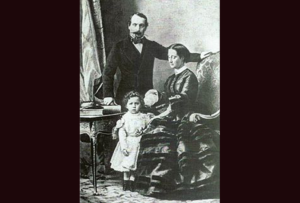

(Portrait: 1857, Eugenie and Charles finally have a live birth – a son who would become Napoleon IV)

Napoleon IV, son of Eugenie and Napoleon III would not survive.. The finally had a live birth of a son – Napoleon Eugene Louise Jean Joseph Bonaparte, Napoleon IV. Unfortunately, Eugene would die at war at the age 19.

(Portrait: Eugenie, Napoleon III, and their son Napoleon IV as a child attend Court in about 1863)

here were Napoleons I, II, III, IV.. but Napoleon III would carry on… On the men’s side, the confusion is in all the men named or whom renamed themselves Louis or Napoleon.

The first Napoleon I had a son with his 2nd wife (Marie Louise) who was his official heir. He was named François Charles Joseph & Napoleon II, but he died as a child.

Napoleon I’s brother’s name was Louis-Napoleon. He called himself Napoleon, as his name, but he did not have title and did not really want it as he was very happily already a political ruler. Louis-Napoleon married Napoleon I’s stepdaughter, Hortense at the request of Napoleon I.

Hortense & Louis Bonaparte (the brother) had a son whom they named Charles-Louis. He called himself Napoleon III & married Eugenie (the ones we are discussing this week). He was the rightful heir, even though he was in political power while Napoleon II was still living, because Napoleon II wanted nothing to do with the throne.

Charles-Louis (Nap III) & Eugenie named their son Louis-Napoleon and called him Napoleon IV. THAT Louis-Napoleon died as a young man.

Got it? Just wait until we get into the Victorias and Eugenies…

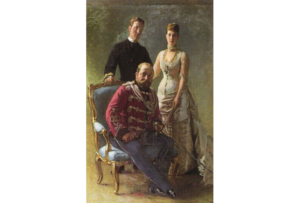

(photo: Eugenie with Napoleon III & their son Napoleon IV; below – same photo session Napoleon III with just his son Napoleon IV)

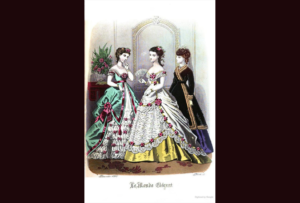

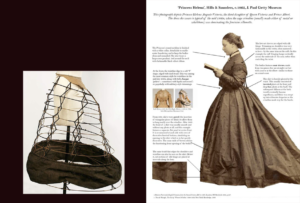

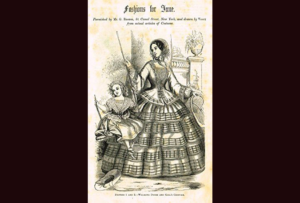

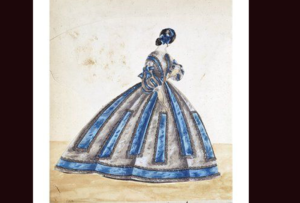

Eugenie of France liked clothing! In 1854 she made the crinoline… Always in a social whirl, or leading a statesman’s event, Eugenie liked to be the focus of attention and dressed to get it. Throughout her life, she hired the finest designers & made them famous.

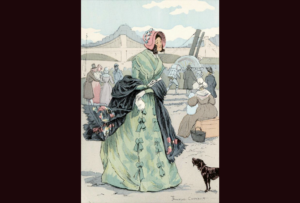

(portrait: Eugenie making the crinoline very popular in 1854. She introduced the hoops to Queen Victoria & England)

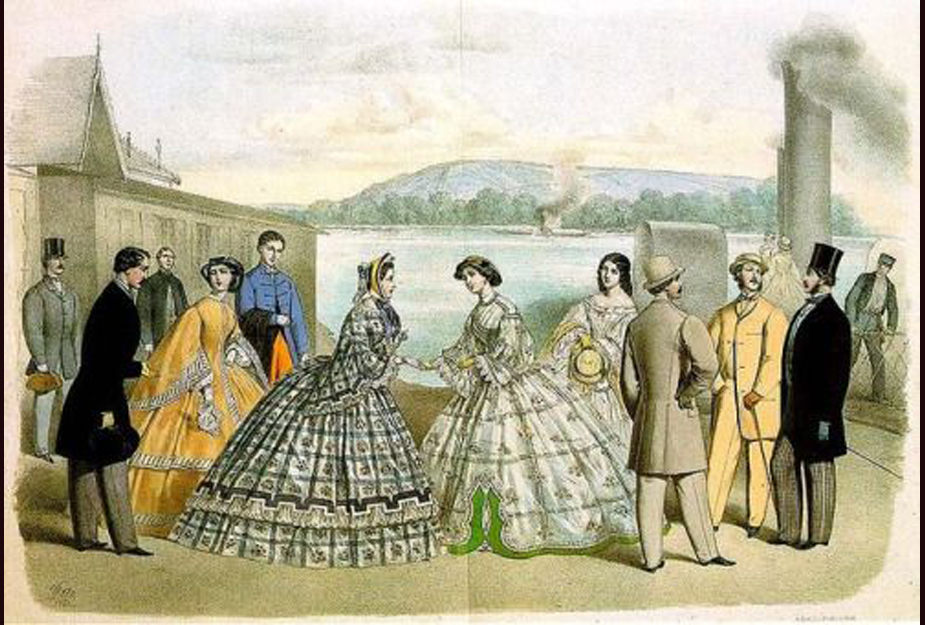

Everyone around Eugenie was fashionable… She surrounded herself with crinoline wearing friends. Often she would hold week long parties at her estate at compeigne.

(Photo: Eugenie – center front – hosts notable women of royal and noble blood at her estate. Most notably are Queen Victoria of England and Victoria’s daughters)

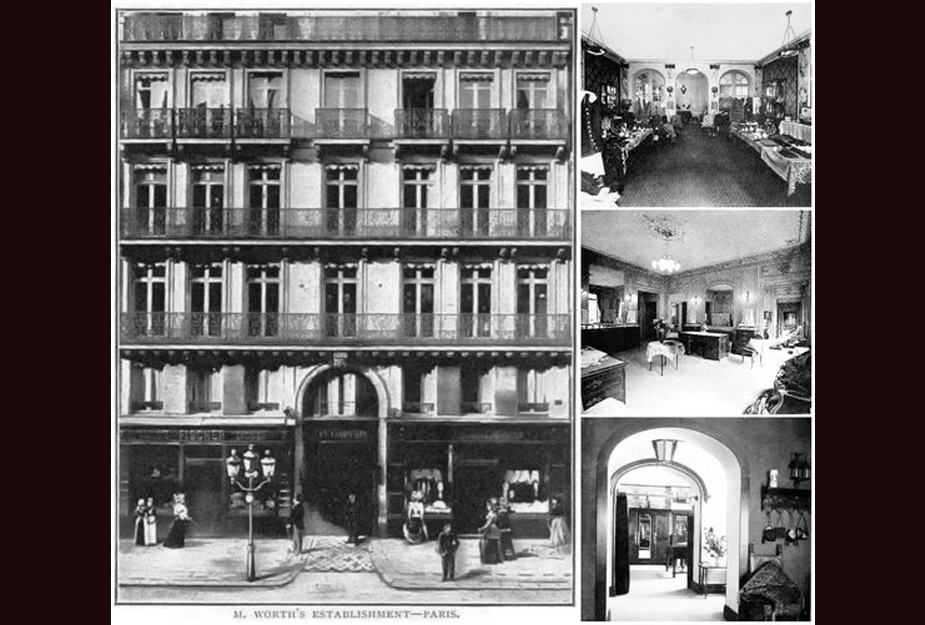

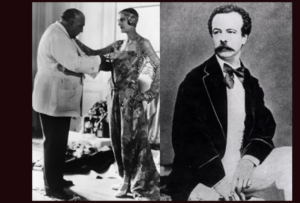

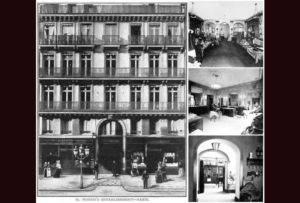

Eugenie ran France while wearing designer gowns… ..In Napoleon IIII’s absence when he was at war (which was quite often), Eugenie ran the country. She supported the garment & textile industries, & hired only the finest fashion designers for herself & her friends.

She was a great customer for the infamous House of Charles Worth in Paris. Worth was an Englishman who introduced fashion shows, salon lighting, designer labels, & most importantly the concept of “costume” – meaning you had to have a different ensemble for each different activity.

(portrait: Eugenie made the crinoline world famous. Following French Royals’ tradition since about 1800, her formal receiving gown included fur.. usually ermine or mink with silk – this designed & made exclusively for her by Worth) Labelled 1852, that would be before her marriage; more likely 1862.

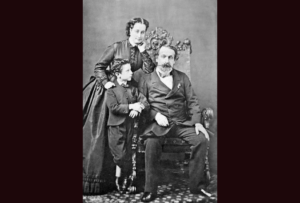

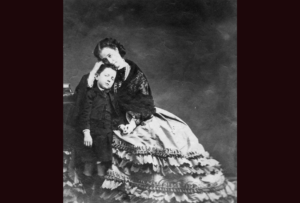

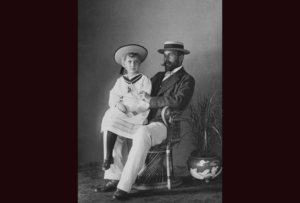

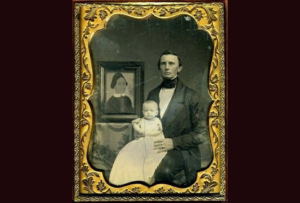

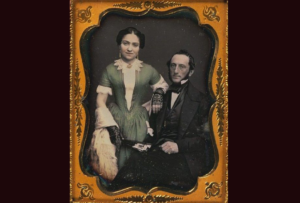

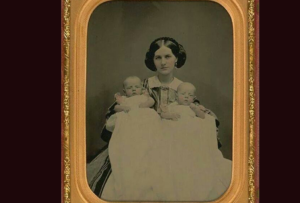

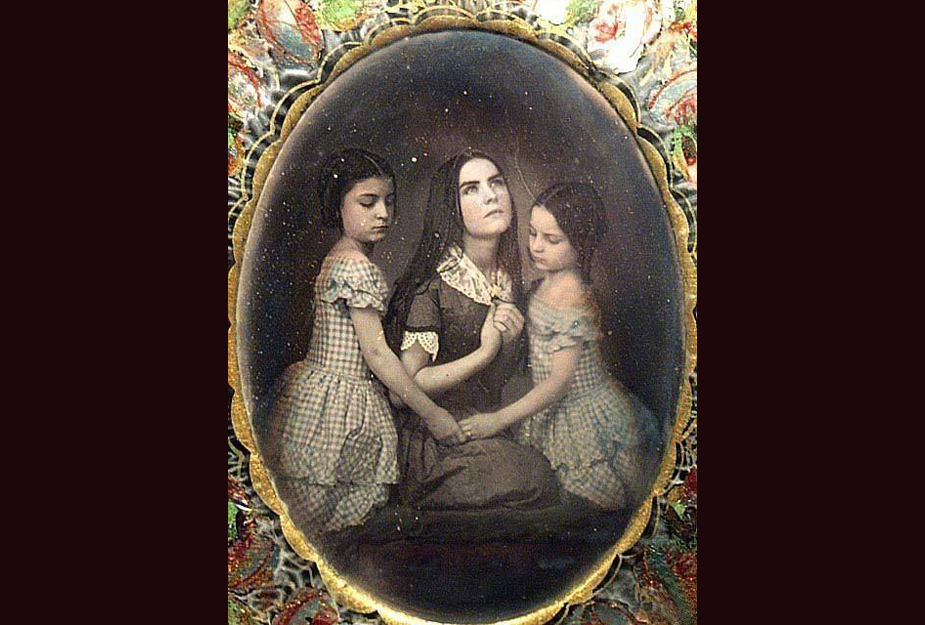

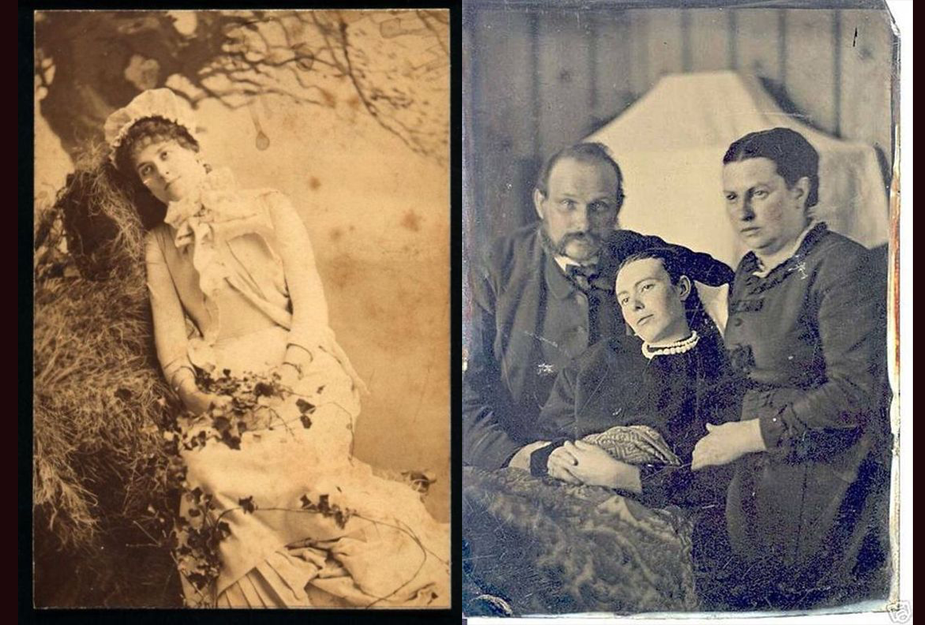

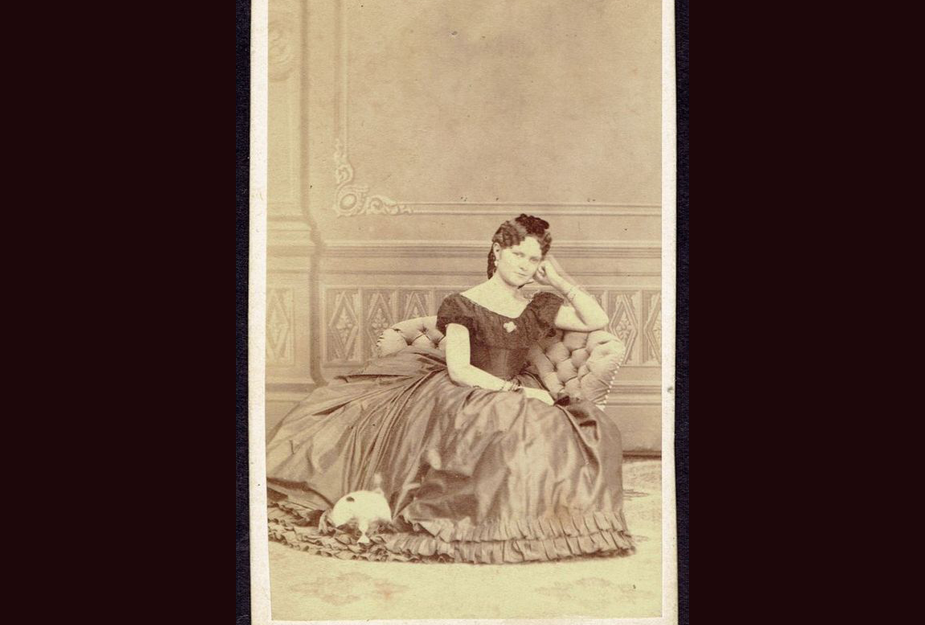

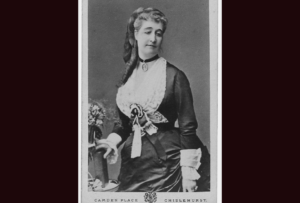

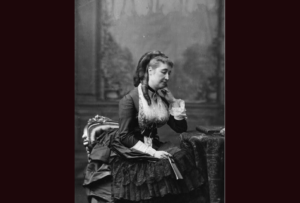

A fashionable portrait of Eugenie with her son in 1862… With the development of the photograph camera by Eastman, the history of Royals and of fashion was now recorded life to death.

While the camera was not yet available to the every day person at the time, portraiture of those who could afford it took on a whole new meaning. While most were posing for stiff and formal portraits only, European nobility had the luxury of documenting every day life through “snapshots” or casual/candid photos such as these of the Napoleon III family in the 1860-80’s.

(Featured photo: In her crinoline sporting black in 1862. Below with her son in 1860 (check out that carpet!)

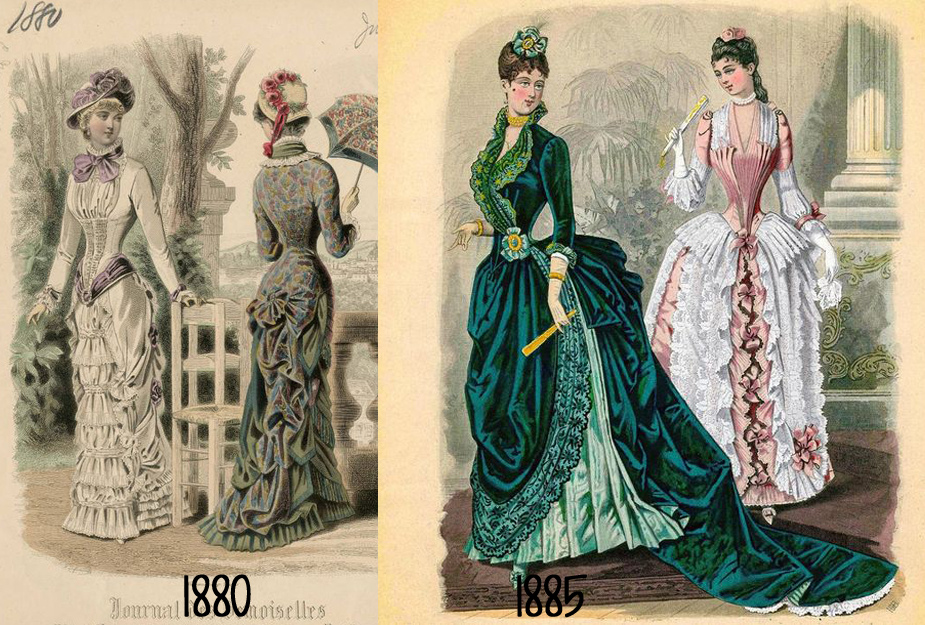

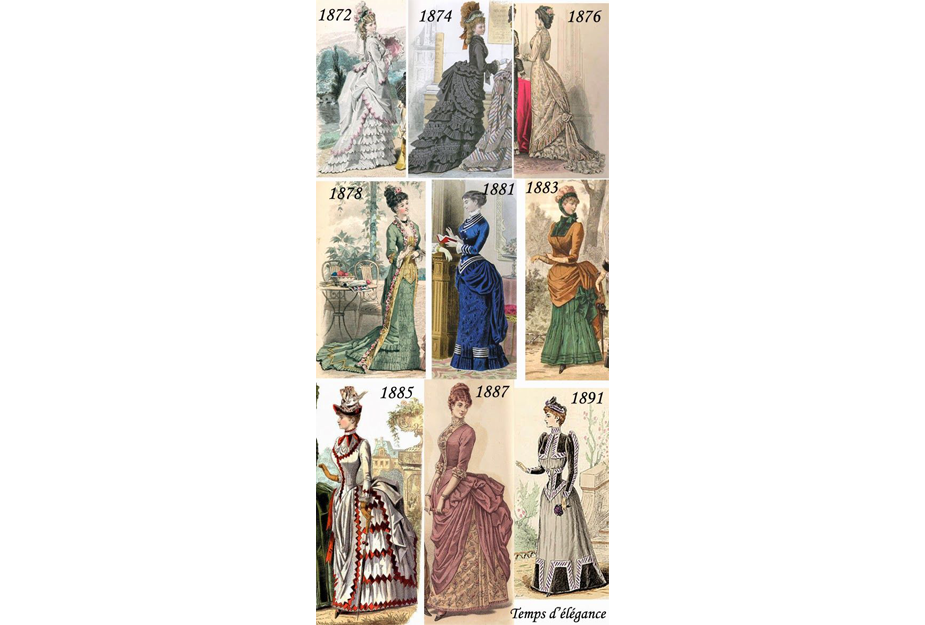

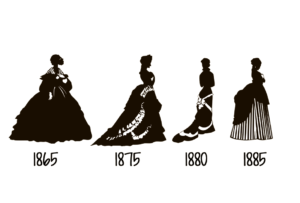

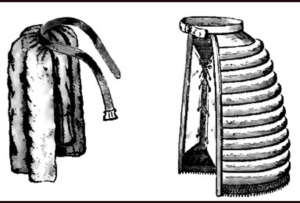

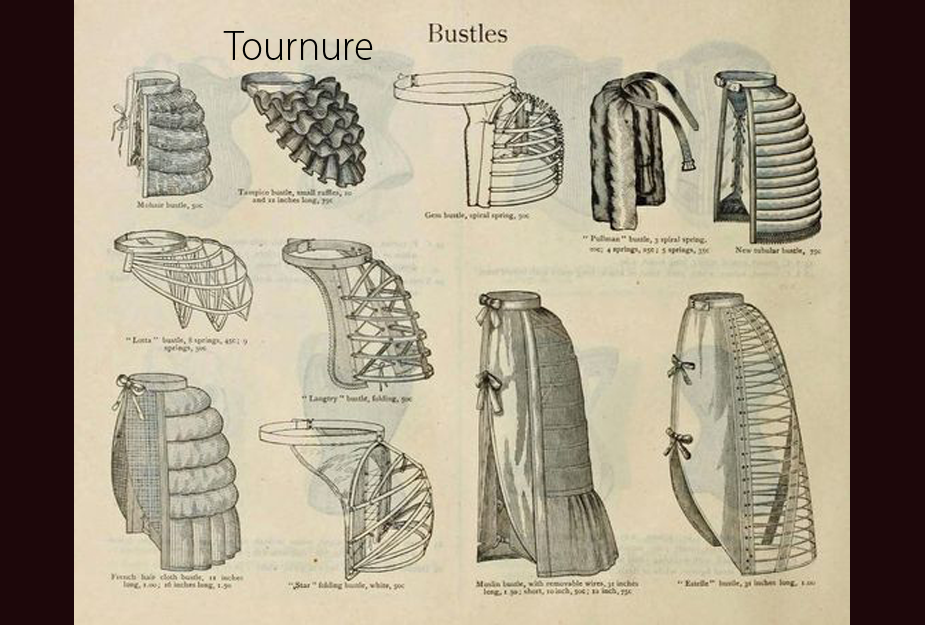

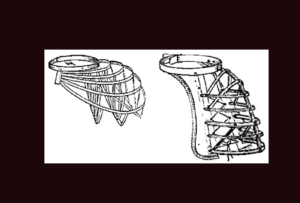

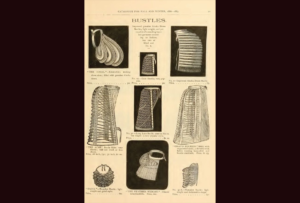

Eugenie influenced 3 fashion periods within the Victorian era.. .. We discuss Eugenie’s role when we get to the “Crinoline Era” of the 1860’s, the “1st Bustle Era” of the 1870’s, and the “2nd Bustle Era” of the 1880’s.

Leading fashion of the world, and being in a position to meet and get to know them. Eugenie directed the Royals of other European influenced countries such as Russia, Sweden, & the Netherlands – even Victoria – during the Victorian Fashion era named for the Queen of England.

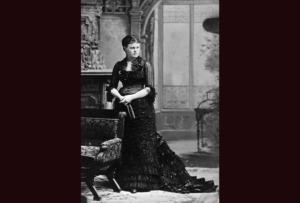

(Photo: A colorful and relaxed Eugenie of France. Because photos of the time were in black and white, we tend to think she’s wearing black or gray, whereas in reality she loved intense, saturated colors including ranges of purple and deep red)

Eugenie influenced 3 fashion periods within the Victorian era.. .. We discuss Eugenie’s role when we get to the “Crinoline Era” of the 1860’s, the “1st Bustle Era” of the 1870’s, and the “2nd Bustle Era” of the 1880’s.

Leading fashion of the world, and being in a position to meet and get to know them. Eugenie directed the Royals of other European influenced countries such as Russia, Sweden, & the Netherlands – even Victoria – during the Victorian Fashion era named for the Queen of England.

(Photo: A colorful and relaxed Eugenie of France. Because photos of the time were in black and white, we tend to think she’s wearing black or gray, whereas in reality she loved intense, saturated colors including ranges of purple and deep red)

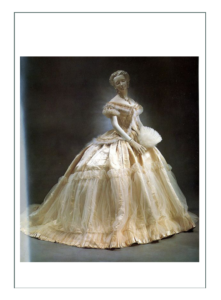

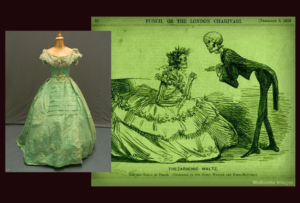

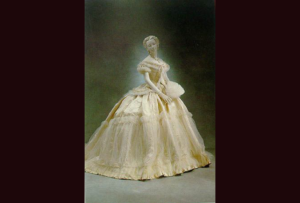

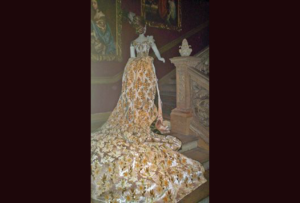

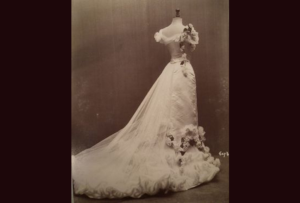

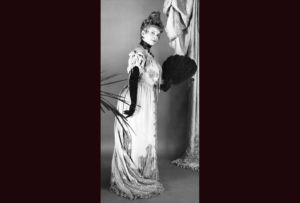

This is a Eugenie’s actual gown in a museum today.. .. Designed by Worth who claims to have “invented” the crinoline, it is typical of just one of many Eugenie of France wore to affairs of state.

One might think this was white silk that had aged to yellow, but we know at this time in the Victorian Fashion Era, that white was specifically designated by Victoria to be for only wedding attire. This most likely was indeed a pale shade of yellow for a ball or Court function.

Eugenie in the 1870’s & 1880’s wore bustles… .. and every fashion ensemble was designed just for her by a world renowned designer.

It was Eugenie who made the designer world renowned.

(Photo: An aging Eugenie wears designer Louis Vitton)

Queen Victoria of England met Empress Eugenie of France… … at Eugenie’s Biarritz, and they became close friends. It was here Eugenie introduced the crinoline to Victoria, which the Queen would take back to England to become an integral part of Victorian fashion.

(Photos: Featured: Eugenie’s Biarritz, on the Cote d’Azure in France, is still a vacation spot; below Palais Hotel in Biarritz, France)

Queen Victoria visited France, and Eugenie visited England.. .. quite often and became very close. One can imagine being a Queen or Empress made it difficult to talk openly and honestly with anyone other than another royal.

We know they traded fashion secrets, because history and the museums document that after a Eugenie visit to England, Victoria would sport the latest Parisian Worth design that Eugenie had just worn on her visit.

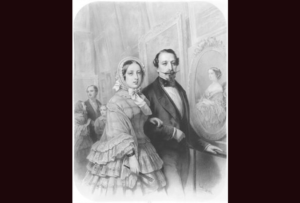

(Painting: The Formal introduction of Queen Victoria of England in 1855 to Empress Eugenie of France. They were actually good friends already, having met informally at Eugenie’s estate)

The Napoleon III’s and Queen Victoria were buddies.. .. visits back and forth between countries, and the marriages of their extended families into the other Royal families across Europe had them quite publicly connected. The eventual use of trains for travel increased the interaction.

(Sketch: Napoleon III of France escorts Queen Victoria of England in an early 1860’s visit to France)

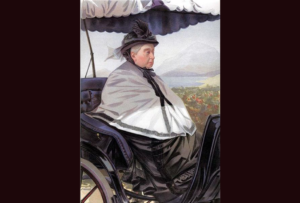

Queen Victoria of England preferred to travel by carriage.. … and as in this portrait in 1897, was still going back and forth between countries to see her grandchildren, whom by that time, were also grandchildren of Eugenie of France. They became one, big family of Royals who spanned all of Europe.

Not limited to clothing, Eugenie was a patron of all the arts.. Eugenie, last empress of France’s introduction of artists & craftsmen of all walks of life improved France’s status in the world of fine arts. She was known for her sponsorship of potters & artists of all types.

(Photo: some of Eugenie’s formal wear jewelry, made especially for her by artists she commissioned, sponsored, or help raise to fame by just wearing their art)

Eugenie’s influence on French fashion went beyond clothing… Eugenie was extremely active in the arts, & attended & sponsored theatre, dance, & visual arts. She traveled extensively including countries like Constantinople, which brought influences of fashion & textiles previously unattainable to prior nobility.

(Photo: a somewhat aging, but forever fashionable Eugenie sports the 2nd bustle which looked like the rear end of a horse; shown here with her husband, Napoleon III)

When Eugenie died, it ended the days of French fashion dominance… there would be many more Eugenies including her namesake, but no one who followed would be able to create, sponsor, wear, and market new innovations like the original Eugenie did.

Some think it was her strong personality and will, some think it was a world with increased exposure to ideas, and some think it was the connections she had to people in positions of power, but there was no one like her again.

The time of French fashion was over.

(Photo: Eugenie in full Court apparel)

Eugenie of France’s end meant the beginning of a new type of royalty… Eugenie lived past her husband and one son, long enough to see the collapse of the European empires. She was exiled, but allowed to return to visit Queen Victoria.

The influence of the two monarchs was profound on world fashion, as they crossed over 70 years of change in the independence of women and from crinolines, to bustles, to bras.

(Photo: A sedate Eugenie in wool, date unknown)

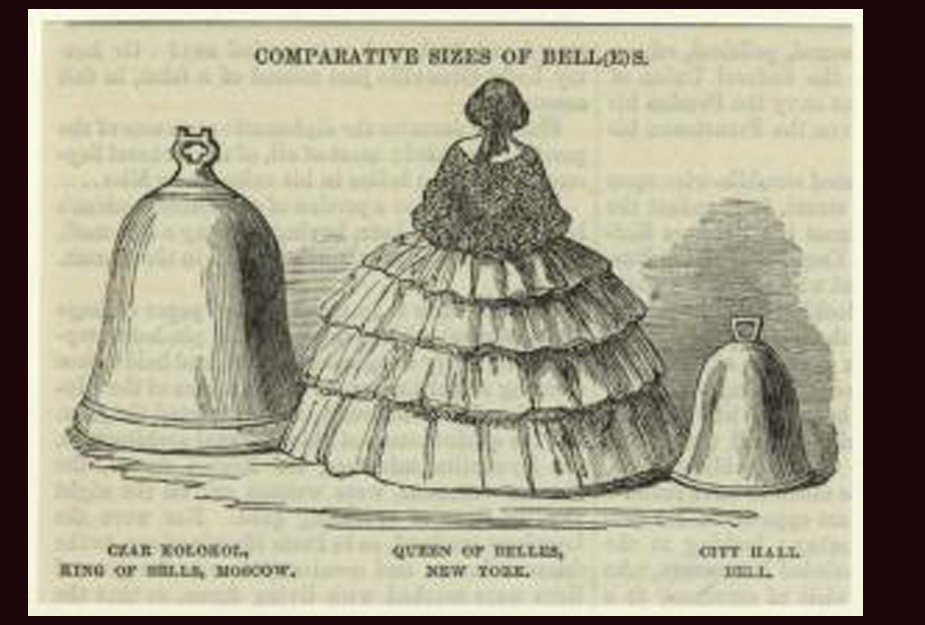

This is how Eugenie of France is best remembered… … and where the “Southern Belle” of the American south got her crinoline fashion should be VERY obvious!

(Portrait: Eugenie introduced Designer Worth’s crinoline innovation to the world in the 1850’s.)

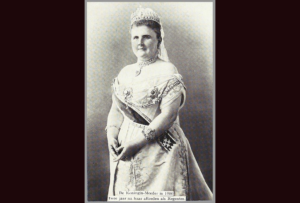

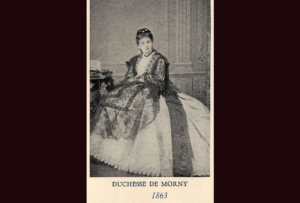

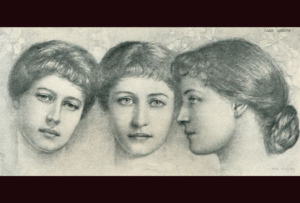

History from this point on, has a lot of Victorias & Eugenies in Europe… .. and the easiest way to tell them apart is their fashion.

History gets the most notorious 2 Victorias and the 2 Eugenies confused a lot, but you can tell by their clothing which one is being discussed. Each went through a specific fashion era, and it helps that they were all very fashionable and up to date with the most current styles.

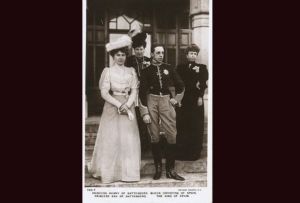

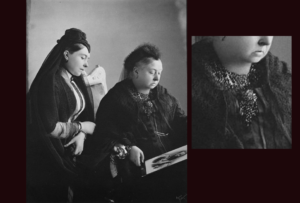

(Portrait: Dowager Empress Eugenie of Spain, goddaughter of Queen Victoria & Granddaughter of Empress Eugenie of France, with Queen Victoria of England in about 1915)

Enter, Victoria

Queen Victoria was THE key fashion influence in the world… … and especially American fashion for decades to come. Starting in 1837 with her coronation, Victoria dictated fashion worldwide. We will discuss Victorian fashion in great detail this winter to come.

(Photo: Queen Victoria of England with her daughter and namesake, Princess Victoria)

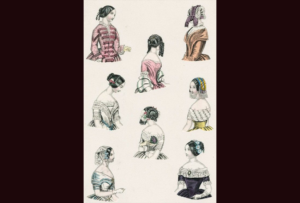

hile Marie Antoinette, Josephine, & others were key influences in the Colonial and Regency Eras worldwide, and so in the new United States of America… .. it was the vast communication network that allowed Queen Victoria to spread her fashion dictates. With the advent of photography in the early 1840’s, people could SEE what she was wearing.

In the days of Josephine, Napoleon sent out fashion dolls – actually tiny dolls – to show what women were to wear. In the days of Marie Antoinette it was words of mouth, sketches, and mostly portraits. Before photography, and in Eugenie’s reign also videography, word of what was in fashion was very limited.

With Victoria and those to follow, every woman knew worldwide what the Queen was wearing today, and she made sure they knew.

(Portrait: Queen Victoria of England as Princess at age 4. Prior to photography, her fashion sense was distributed by paintings and sketches)

We start the Victoria & Eugenie connections with Beatrice.. … One of Queen Victoria of England’s daughters. Beatrice, the youngest and 5th daughter, was the Queen’s assistant. They were very close. It was natural Beatrice would also become close friends with Victoria’s new French friend, Empress Eugenie.

(Portraits: Queen Victoria and daughter Beatrice in 1863.. always in the height of fashion for child or adult – this being the crinoline era for all. In the US at the same time, America was smack in the middle of the Civil War)

Princess Beatrice of England, Victoria’s daughter… … married a man from a “non-Royal” family, but with the Queen’s blessings. Beatrice had a daughter in this marriage whom she named Her Highness Victoria Eugenie of Battenburg. Queen Victoria granted this granddaughter the title “Highness”.

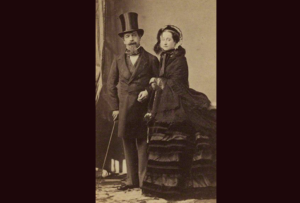

(Photo: yes photos now! Beatrice in the height of 1885 fashion – just before the BIG bustle, and with her husband Henry of Battenburg in 1886)

You can tell which Beatrice, Victoria, or Eugenie in history is by the clothing… if you know roughly the years of their adulthood. Always the height of fashion, from Queen Victoria’s 1837 forward, the English Royals were on top of it. Before that it had been the French.

French influence was fading fast with only Eugenie left at the height of fashion in the 1850’s-’60’s. Queen Victoria took command of European and American fashion, but with the Asias becoming accessible, and travel and communication opening up the globe, by the end of Victoria’s reign there was a virtual “explosion” of fashion ideals with influences from every country in the world.

(Portrait: Even in 1928, Her Highness Beatrice of Battenburg (daughter of Queen Victoria of England) wore the height of fashion. Note the pearls that were handed down from mothers to daughters, and the middle eastern influence in the fabrics and patterns by the ’20’s in this picture.)

Beatrice, daughter of Queen Victoria would become… .. the last Empress of Prussia when she married Henry of Battenburg. Beatrice, the companion and confident of her mother, had said “I don’t like weddings. I shall never marry.”

She fell in love with Henry after meeting him at her niece’s (another Victoria) wedding. Victoria did not want Beatrice to leave, so made the deal with the newlweds that if they would live in the palace and take care of Victoria until her death, she would permit the marriage.

Beatrice and Henry were married in 1885.

(photo: The Battenburgs on their wedding. Note the distinctive fitted and flat front of the high style of the day, with the bustle, at this time mostly fabric with a pad support, that would become the largest one in history by the next year 1886)

Her Royal Highness Beatrice of Russia took care of her mother… .. Queen Victoria of England. She and husband Prince Henry lived in the palace, and eventually Victoria realized they needed space of their own and gave them an estate nearby.

(Photo: Beatrice and Henry official portraits 1886)

Henry, Queen Victoria’s son in law, wanted to help the English military.. He “escaped” life in the palace often to participate in English campaigns, but Beatrice, Henry’s wife and Victoria wanted to keep him closer to home. Prince Henry on one such excursion in the Anglo-Asante War, never returned. He died of malaria, sending Beatrice into deep mourning.

(Photo: Henry of Battenburg, of the Prussian House of Hesse in the late 1880’s wearing a plaid. Queen Victoria loved the kilts and plaids of the Scots, and brought the styles and patterns into English daily wear, and so, worldwide fashion)

Beatrice and Henry had 4 children… .. and they were the great grandparents of the current ruler of Spain, Felipe VI.

(Photo: Henry, Beatrice Queen Victoria’s daughter, and children around the table with Queen Victoria in Windsor Palace. Note Victoria’s loyal Indian servant, Muhri, in the background of this and other photos)

Beatrice’s Brother in Law was King Frederick of Prussia.. … which ties the English Royalty into the French (and obviously Prussian) Royalty.

(photo: The Hesse family of Prussia, including Beatrice, Henry, their children, and loyal servant Muhri, gather around Queen Victoria. Although the photo is not dated, the HATS and slim, no bustle profile of the skirt, indicate this to be around 1883.)

Beatrice and Henry had children.. … the Royal Family of England, now tied to royal families of Prussia through this marriage, had:

Alexander, 1886; Ena (Eugenie, we will discuss in a bit), 1887; Leopold, 1889; Maurice, 1891

(Photo: Beatrice with her mother Queen Victoria and Henry and kids in about 1890. Note Victoria setting the fashion trends – as always through her reign!)

HRH (His Royal Highness) Beatrice’s youngest son Maurice was killed in World War I… … the grandson of Queen Victoria of England, and son of her youngest daughter Beatrice. It was a great loss to the royal family.

(Portrait: Maurice just before his death in full military dress)

Beatrice comforted her mother Queen Victoria.. … until Victoria’s death. Beatrice, talented in singing, and with a passion for photography, had been given by her mother a photographic dark room. She continued her artistic pursuits throughout her life.

(Portrait: 1908 Her Royal Highness Beatrice)

Her Royal Highness Beatrice of Battenburg became… … Her Royal Highness Beatrice of Mountbatten.. when King George IV suceeded her mother to the throne of England in 1917. Her last official public appearance was at his burial in 1944 when she was 87 years old.

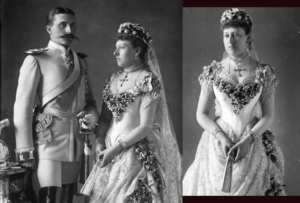

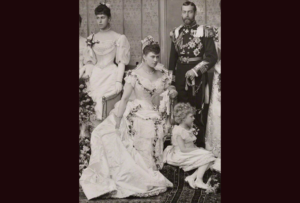

(Photo: King George IV and wife Mary on their wedding day in 1893. THIS shows the HEIGHT of world fashion of the day – the corset is of particular note, plus the shape of the dress. Bustles were out; Edwardian skirts were coming in)

Back to the Eugenies… Queen Victoria’s granddaughter from Beatrice… … Her Highness Victoria Eugenie of Battenburg.. was named after Queen Victoria of England and Empress Eugenie of France. Eugenie of France was Victoria Eugenie’s godmother – uniting the two countries as only women could do – through love of fashion, country, and family.

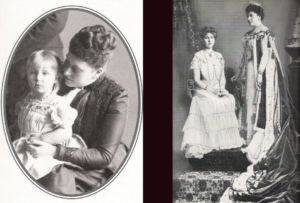

(Photo: Beatrice with her only daughter, though she had 3 sons, called “Ena”)

Beatrice, daughter of Queen Victoria, and her daughter, Ena.. … were both hemophiliacs, a rare disease affecting the ability of blood to clot. This was a genetic trait handed down on Victoria’s side, and one of the reasons the Queen was hesitant to permit her daughter to marry.

In the end, it would be Ena who was most doted upon by all, and connected Royal blood between France, England, and Russia.

(Photo: Beatrice with a teenage daughter Ena in the 1890’s)

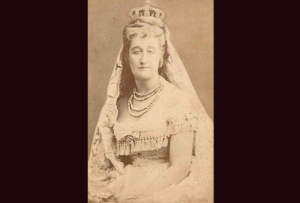

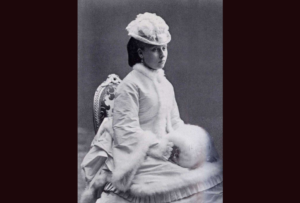

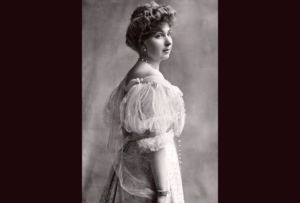

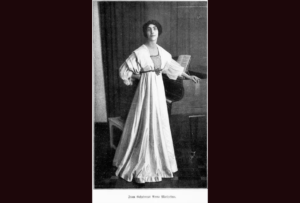

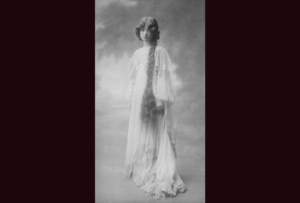

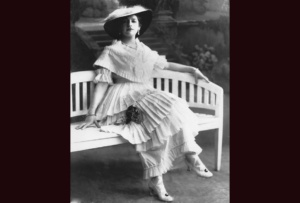

Victoria Eugenie of Battenburg, “Ena”, granddaughter of Queen Victoria, is well illustrated… … and known for her fashion, as photography was at last developed so that a woman’s life could be accurately documented from birth to death.

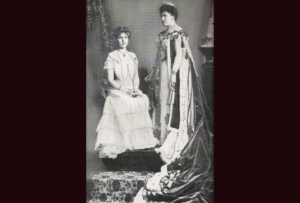

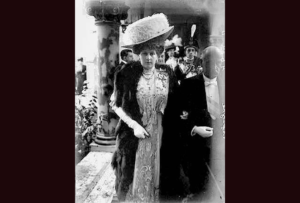

(Photo: Ena with her husband and an aging mother Beatrice, in the height of fashion in about 1895 – the high sleeves of late Victorian style as it merged with what would become the 2 piece blouse and skirt of the Edwardian fashion era)

There are MANY photos of Victoria Eugenie, granddaughter of Queen Victoria… .. goddaughter of Eugenie of France. She was, of course, appropriately fashionable in each era.

(Photo: Victoria Eugenie in the mid 1890’s)

With the ease of new photographic methods… .. the Royal family could now be followed in their daily lives. They still loved the posed portraits when everyone was able to gather though.

(Photo: 4 generations of English royal women: Victoria with daughter Beatrice, granddaughter “Ena” Victoria Eugenie, and Ena’s daughter Alice the baby)

Well photographed Princess Beatrice, who would become Her Royal Highness of Battenburg, console her mother Queen Victoria at the death of her father Albert, and care for her mother the rest of Victoria’s life.

(Featured: in high winter fashion. below; as the companion and secretary to her mother)

Ena, granddaughter of Victoria, and daughter of Beatrice.. .. was the godchild of Eugenie of France. Ena brought the families and countries together.

She was the last Empress of Spain before Spain became a Republic.

(Photo: Well photographed by her mother, an excellent photographer with her own dark room, Ena is in the height of royal fashion during a casual moment with her sons)

ere are more photos of the fashionable and well documented Ena… … connected by blood to royalty of 4 nations: England, France, Spain, & Prussia.

(Photo: a young Ena (Victoria Eugenie of Battenburg), later to become Ena of Spain)

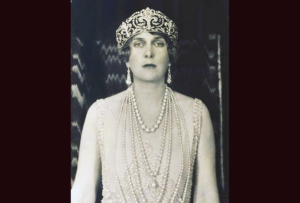

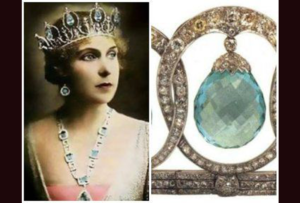

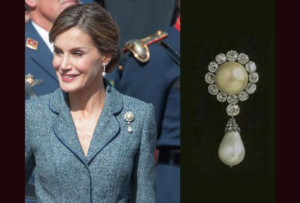

English royals left their jewels to the next generation… …Sometimes that meant tiaras, necklaces, and bracelets left the country forever.

This photo shows Ena, daughter of Beatrice, Queen Victoria’s youngest & goddaughter of Eugenie of France, wearing the English royal pearls – in Spain.

Ena, granddaughter of Queen Victoria & Goddaughter of Empress Eugenie… … inherited much royal jewelry from both, plus a flair for fashion.

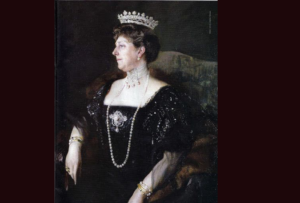

(Portrait: Ena, Empress of Spain, wore her grandmother, Queen Victoria’s aquamarine and amethyst prarure)

It’s interesting how the Royal women wore antique jewels.. … as with modern day Josephine of Sweden shown here wearing her great grandmother Empress Josephine of France’s favorite cameo tiara (prarure), it’s amazing how well the same jewels will go with any fashionable ensemble of any era.

(Portraits: left, Empress Josephine of France; right, Josephine of Sweden)

Modern Queens wear modern clothes & ancient jewelry… … here we see Queen Elizabeth, current monarch of England, wearing Queen Victoria’s mother’s approximate era 1830 brooch.

Yet another Royal pulls off a fashion feat… … wearing Queen Victoria’s brooch, Queen Letitzia of Spain has inherited English, French, and Spanish jewelry. An absolutely stunning woman who was a journalist and news anchor before marrying Felipe to become the Spanish Queen, she wears the tiaras, prarures, and brooches of her ancestors proudly and often.

Ena, granddaughter of Queen Victoria of England, lived in a magical time… .. when fashion was changing. Being a trendsetter did not always mean being well coordinated. Here is Ena, in ermine, silk, and the Royal pearls (of course), sporting a 1920’s number at a dedication ceremony, proving pearls do not necessarily always go with everything (as they would say later in the ’50’s).

Note that by this time silk was no longer the crisp and starchy taffeta of her grandmother and greatgrandmother, but a soft, drapy fabric that clung to the body – unless it was worn in the very straight style of the era.

Ena was loved by all, including her father… … Prince Henry of Battenburg. Named after her grandmother Queen Victoria of England, and her godmother Empress Eugenie of France, Victoria Eugenie had a casual relationship with her elders in private. She called Victoria “Gangan”.

Ena first met her future husband when she was 17. King Alfonso XIII of Spain was 19 when they met in 1905, during his tour of Europe in search of a bride, at a dinner gathering at Buckingham Palace.

It was rumored Alfonso had Victoria Eugenie’s cousin, Princess Patricia of Connaught, in mind, but that rumor went straight out the window when Alfonso set his eyes on Victoria Eugenie. This was no loss for Patricia since she made it evidently clear that she was not marrying the lustful Alfonso.

(photo: Ena on her father Henry’s lap)

Victoria Eugenie (“Ena”), Queen Victoria’s fashionable granddaughter… .. had a life of ups and downs. When she met her eventual husband Alfonso of Spain, she was only 17. He had a fiery and passionate temperament, while she was shy.

He was worried about the possibility of her carrying her mothers’ dreaded haemophilia blood disease and passing it on to his heirs, thus bringing it to his country. Alfonso’s advisors warned him that it was most likely she had it since it was genetic and because her brother was very ill from it, but Alfonso pushed their concerns aside. He couldn’t understand why the healthy and beautiful Ena could be ill.

(Photo: Ena and Alfonso on their wedding day. White by now was the accepted color for weddings, courtesy of the dictates of her grandmother. Note Alfonso’s cigarette burning, even in his royal portrait, indicating his “rogue” personality that would come into play later in their lives…)

Ena of England and Alfonso of Spain also had problems.. … with religion. Ena had been raised a Protestant, and all Spanish royalty, to which she would belong, was strictly Catholic. Ena’s English supporters did not want to be associated with Rome or Catholics.

People of all social status had heated discussions which made Victoria Eugenie feel very low at the beginning of her relationship with Alfonso, for causing such conflict.

(Photo: this might have been taken by Ena’s mother, Beatrice, who had a dark room and portable camera. Taken on their wedding day, you can see Ena was not the slim corseted profile her front view indicates. Typical of Edwardian fashion, the back of her gown would be trained and full).

Ena learned Spanish during her brief marriage engagement period… … because she would become the Queen of Spain, giving up all rights to the British throne. Spanish and Spanish culture was difficult for her, and she only had a few months to learn it. She converted to the Catholic faith before marrying.

(Photos: Left Ena in full Spanish court splendor; right her mother Beatrice in full English court splendor, but it’s silk that reigns!)

Ena and Alfonso’s marriage had a frightening start… … when a bomb went off near their carriage as they were leaving the Church of San Geronimo in Madrid.

The new queen appeared calm at the time, but when she got to the Royal Palace, she was on the verge of hysteria. One can imagine marrying a known “rake”, speaking a foreign language, leaving all that you knew, converting to a religion you don’t want, and having to face down a bomb AND a wedding night in one afternoon was a bit sressful.

(Photo: Bomb going off May 31, 1906 next to the carriage of the just married Victoria Eugenie, Queen Victoria’s granddaughter, and her new husband King Alfonso of Spain)

The new King and Queen of Spain, Ena and Alfonso… .. got along well enough, until his worst fears were realized that she proved to have the genetic disease hemophilia.

(Photo: Ena and Alfonso’s different personalities are very clear on this candid shot during their honeymoon in 1906. The advent of cameras had its drawbacks, as now there were photographers documenting every breath of the Royals around the world)

The wedding gift from Alfonso to his young bride has been handed… … down to each generation of women in the Spanish royal household. Called “La Buena” prarure, Letizia of Sweden’s mother (right) wore Ena’s (center) wedding crown, and Letizia (left) has it today.

Ena and Alfonso of Spain appeared to be happy at first.. .. unfortunately, when they found out their first son Alfonso was also a hemopheliac (genetic blood disease), their wedded bliss fell apart. Alfonso responded by having liasons and affairs with several women.

He humiliated Victoria Eugenie (Ena) by having many illegitimate children. Some small videos from an Easter celebration in Seville in 1930 show how detached the king and queen were from each other by then.

Ena was very unhappy, but she looked the other way and continued her “queenly duties”.

(Photo: Ena with her young children)

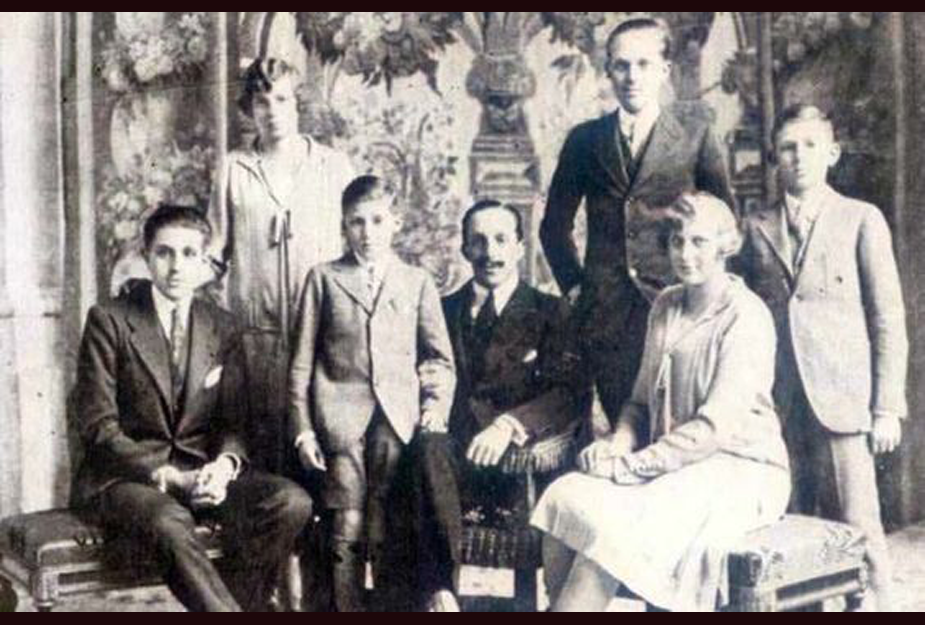

Despite it all, Ena and Alfonso had 7 legitimate royal children…

- Alfonso in 1907

- Jaime in 1908

- Beatriz in 1909

- Fernando in 1910 (who was stillborn)

- Maria Cristina in 1911

- Juan in 1913

- Gonzalo in 1914

(Photo: Victoria Eugenie and Alfonso with their Spanish royal children. Note by this time in the 1920’s, that only 1 of the 7 died, and that not in the first year, but at birth, attesting to improved health conditions at the time. Their ancestors would have lost 2 or 3 AFTER a live birth within the first year from 10 or 11 pregnancies typically).

Queen “Ena” of Spain did not like bullfights… .. which made her Spanish subjects very mistrustful of her. Many found her to be “too English”, despite her constant efforts to follow Spanish customs and adapt to the culture. Along with the constant threat of revolution with countercultures, bombing, and threats on her life, Ena had a lot to deal with – from her husband’s infidelities to the populace disliking her.

(Photo: Ena takes a moment to rest from her worries and play tennis in the latest sporting fashion. Note the stripes – considered “casual” and worn at this time for sportswear only along with polka dots).

Ena reorganized the Red Cross of Spain… …There was strife and unrest in Spain during the time of Victoria Eugenie’s and Alfonso’s reign. Ena’s records show she complained to her ladies in waiting that Alfonso took “bad political advice”.

Between that and the populace’s general mistrust of her, that she had personal crises. To handle that, she turned to humanitarian work. She gathere

d Spanish currency, called pesetas, healthcare supplies, and clothes for the ill and injured Spanish soldiers who were in Morocco in the war in North Africa.

This effort re organized the Spanish Red Cross, which had been founded in 1864 for worldwide relief. She updated Spanish methods using those she learned from other European countries, such as personal hygiene and use of sanitary and modern medical supplies.

(photo: Ena in her Spanish Red Cross Uniform about 1910)

Beatriz Ena’s daughter Beatriz, continued the Red Cross tradition… Thanks to the queen’s efforts, the first Spanish Red Cross hospital was opened in 1918 in Madrid. Both of Victoria Eugenie’s daughters, Beatriz and Maria Cristina, would receive their nursing training there nearly a decade later.

Victoria Eugenie received many awards for this. Some of these awards included the Silver Cross of the Red Cross from Venezuela, the Italian Red Cross Medal, and the Golden Rose of Christianity from Pope Pius XI in 1923.

(Photo: Infanta Beatriz proudly wears the Red Cross uniform of Spain)

Ena’s 2nd daughter, Maria Cristina also wore the uniform… … of the Red Cross of Spain. She entered service alongside her mother, Victoria Eugenie Queen of Spain, and her older sister, Beatriz.

(photo: Infanta Maria Cristina (same status as an English Princess)

We stop here with this generation, as we have already strayed into the Edwardian Era, and will now define the fashions of the Victorian Era, now that we know the key influencers of fashion.

Many Factors Creating Fashion

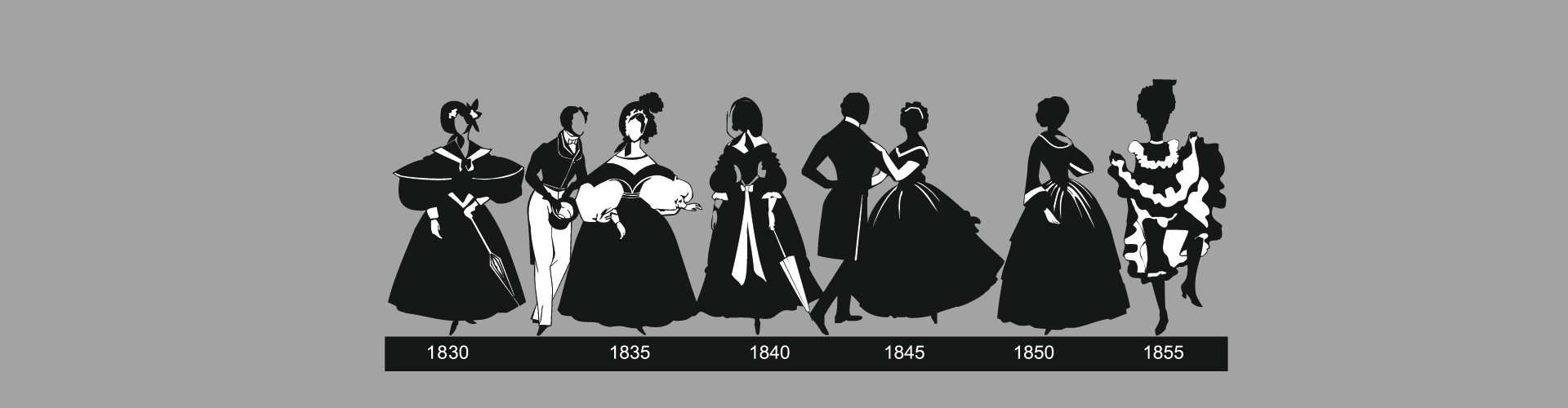

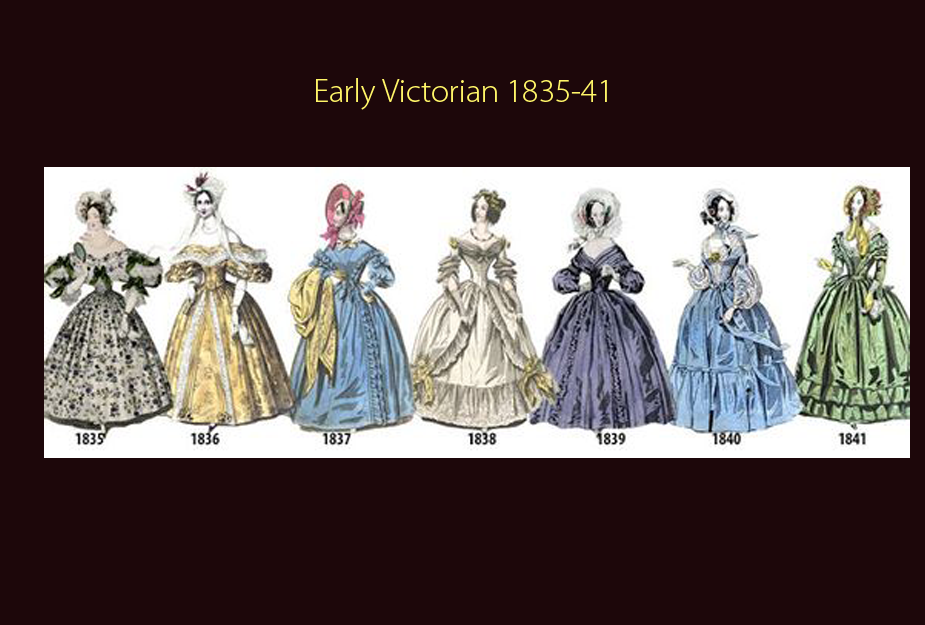

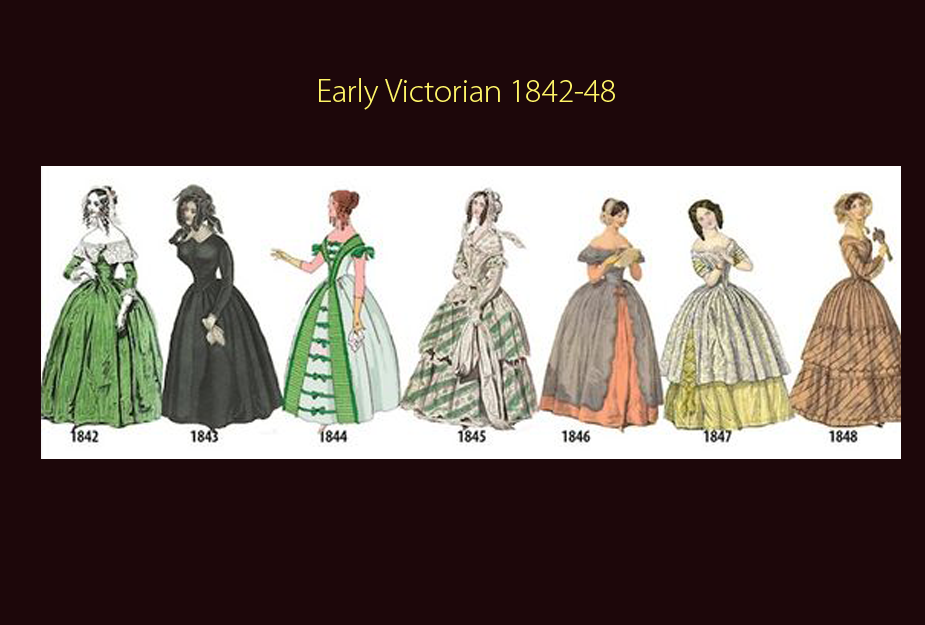

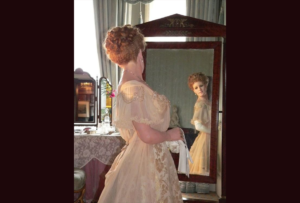

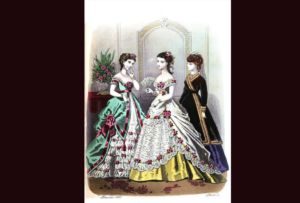

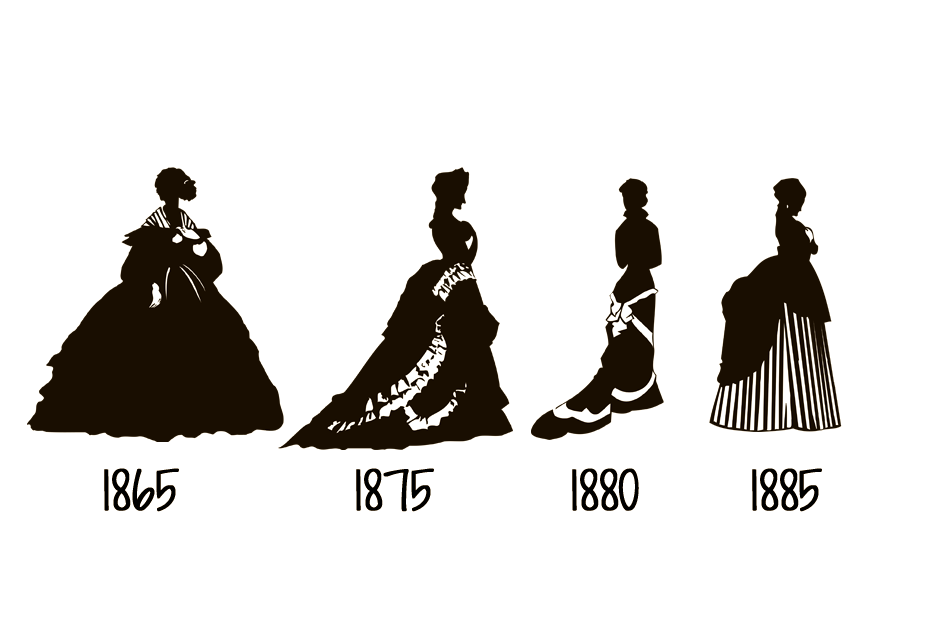

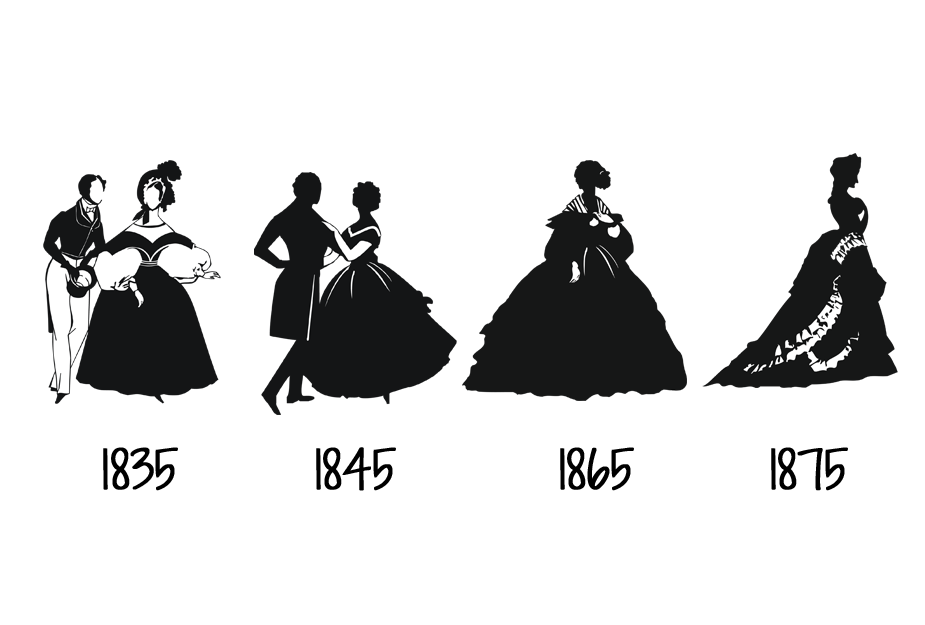

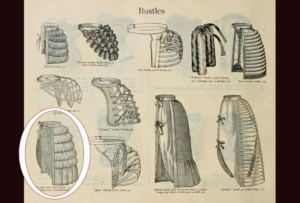

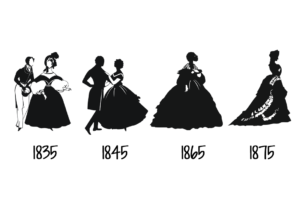

There were 3-4 evolutions of Victorian style, with crossovers and modifications, but basically there was “early”, which was like ornamented Regency, “middle” with bustles and crinolines, and “late” with more bustles and the black for mourning and white for weddings dictates.

1830-1855 as shown was “early”.

The Victorian Era was next led by… … surprise! Queen Victoria of England who dominated almost 60 years of fashion worldwide. Her exacting dictates regarding “costume” – every event had a specific fashion – led to white for weddings and black for mourning, which switched the previous rules.

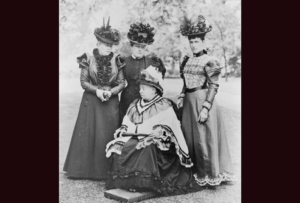

Even to her end, she was fashionable, and demanded it of others. Here she is in the 1880’s with (left to right) 1st born daughter Victoria “Vicky”, last born daughter Beatrice, and granddaughter Irene.

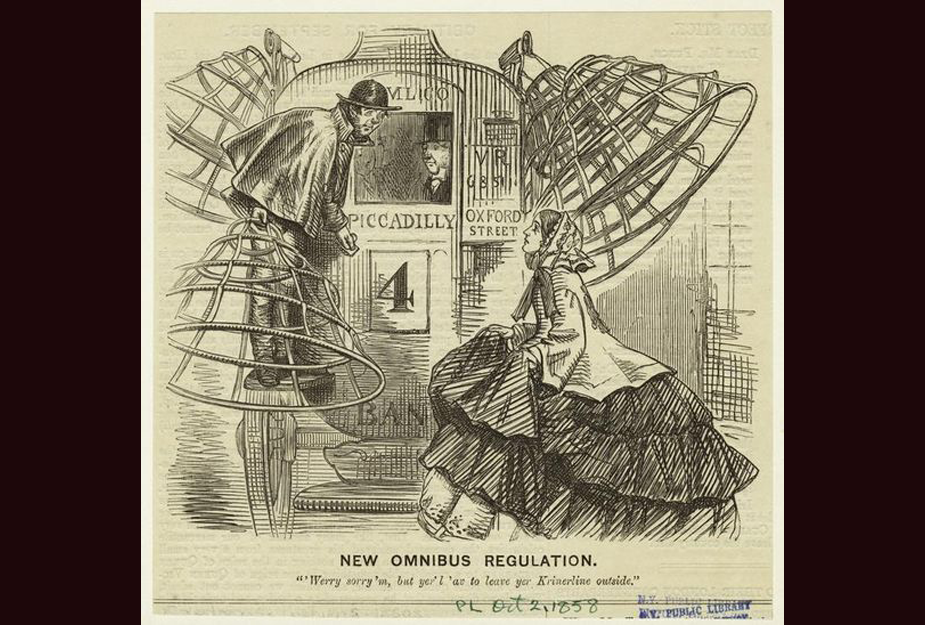

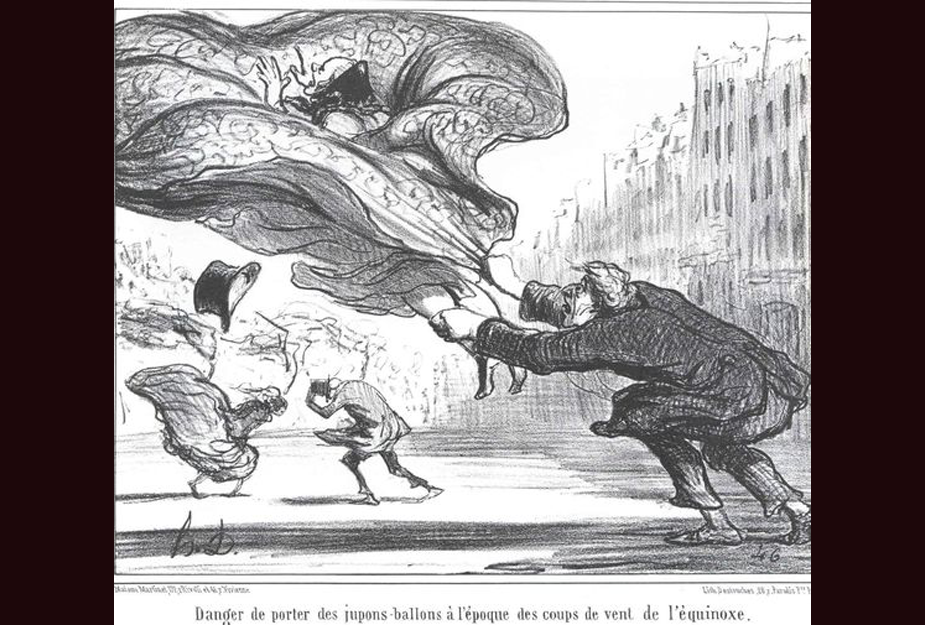

Queen Victoria’s buddy also influenced Victoria fashion… … Empress (later wife of the President when the empire was dissolved) Eugenie of France was another key fashion figure of influence. You can imagine the mix of admiration, curiosity, jealousy, and giggling when Eugenie first showed Victoria the new 8′ crinoline hoops.

(Portrait: Eugenie in about 1862 in just one of her many Charles Worth, Parisian designer hoops and crinoline ensembles – rare in gold, because she usually wore purples and blues)

Victoria Eugenie “Ena”, Queen Victorias granddaughter… … the Queen of Spain and goddaughter of Eugenie of France was the next key fashion influence. Her “hey day” was the Edwardian Era, although she was stylish well into the 1920’s.

(Photo: Ena in about 1906 after her marriage)

And one more key fashion influencer, Edwardian… … Alexandria of Russia. She was THE favorite in America during the Edwardian era because they were buddies with the US president at the time. She carried “La Belle Epoque” (French Parisian High Fashion) into the “Titanic” eras – along with famous Parisian designers introduced the Princess Line.. the hobble skirt.. and the tango shoes.

After that, World War I entangled all countries, affected all women, and changed fashion forever in a virtual explosion of ideas and innovations. That’s why we stop depictions at 1914.. on the ledge overlooking a complete change forever.

(Alexandria at the height of her power in 1907 and with the height of her princess waistline. Unfortunately, Alexandria and all the Romanov family would be horrifically executed when Stalin and Lenin took over during the Bolshevik Revolution)

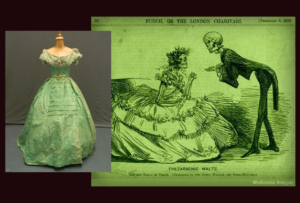

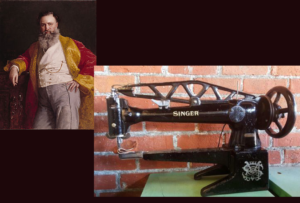

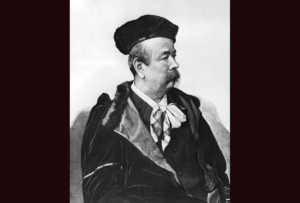

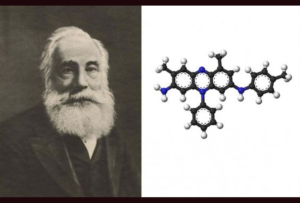

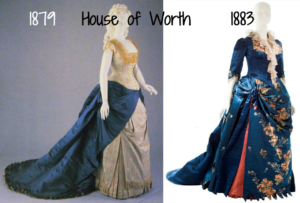

Queen Victoria competed with the influence of French fashion designers. Charles Worth of Paris was actually from England, but made a name and had extreme input to Victoria’s style. He invented the term “costume”, meaning “the right thing for every event”, and he introduced crinolines and hoops.

His costumes for balls and masques introduced new ideas that would be used in the early 1900’s as designer Poiret’s “hobble skirt”.

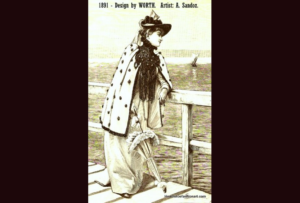

(Left: Charles Worth gown 1865 with hoops; Right: 1870 ball costume)

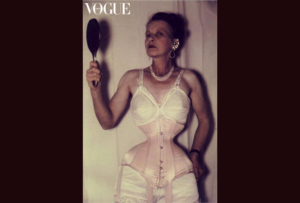

Designer Worth and his son who took over the business.. .. crossed over into the Edwardian era. His Parisian House of Worth was “La Belle Epoque”, and embraced the corsets and lines of the Edwardians as well as Edward himself. Edward’s wife and most royals of the world wore Worths.

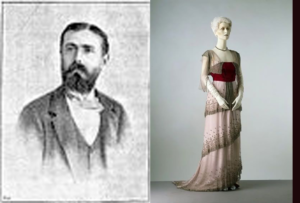

(Left: Charles Worth gown 1882 Victorian; Right: 1901 Edwardian)

Notice after Victoria, they aren’t Key WEARERS, but Key DESIGNERS… … the world had changed, communications had changed, political boundaries had changed, and so loyalties had changed. In America in particular, there was an explosion of ideas and technology and so fashion. Countries worldwide were influenced by – countries worldwide – and not people of fashion specifically.

Notable designers like Poiret and the Callot Soeurs of Paris set the stages (literally, as in theatre) during the Edwardian era and beyond. Hundreds of designers would follow.. Coco Chanel.. Paquin… Gioseffi..

(Left: Paquin gown; Right: Poiret hobble skirt sketch)

We saw influential old friends brought back by Edwardian designers… … Charles Worth, top designer through Victorian and Edwardian eras (late 1800’s and early 1900), claims to have invented the large paniers and short shepherdess look.

We know better, as proven by the 1776 real garments on the left, and the 1850’s Worth sketch on the right.

Queen Victoria of England reigned… …over England for 64 years. Crowned at age 18, she also ruled over fashion from 1837 until her son Edward’s flippant styles crossed over hers into the Edwardian Fashion Era around 1900. 1837 to (about) 1891 are called the “Victorian Years” in fashion. This applied to clothing, furniture, and anything that was crafted or created by an artisan.

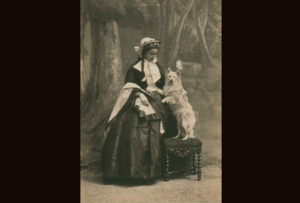

(Portrait: Victoria Duchess of Kent as a preteen with her spaniel, Dash)

When Victoria became Queen of England in 1837, she was 18 years old. In 1837, it was still the Regency Era – defining fashion and attitudes – coming off the former King Georges and influences of the French under Napoleon Bonaparte.

Regency’s “little white dress” had evolved into elaborate Rococco ornamented styles, lower waistlines, and stiff, “tinkle bell” shaped skirts that would become the signature shape in the ’40’s and ’50’s worldwide.

(Portrait: Queen Victoria in 1843, 6 years into her reign and 24 years old. You can see the Regency shape morphing into something new.)

When Queen Victoria of England married Albert of Saxe-Coburg… .. in about 1840 , “Victorian” dictates took definite shape. It was defined by Victoria’s “prudish” attitude and strict rules for moral behavior that lasted until about 1890 when Prince Edward the Prince of Wales and his high spirited “Edwardians” took over societal conduct even though she was still ruling.

(Photo: Queen Victoria with son and future King Edward in 1897 near the end of her rule)(Below: Albert, Consort (husband) to the Queen)

England’s world status defined world fashion… .. Remember the 6 Key Concepts from last month that affect fashion? Technological developments, industry, and so economic status directly affected what women wore at any given time. In England, a big part of that was class status as it changed.

In America of the 1840’s, because women were still looking out of the corner of their eyes at the English and French.

(Photo: A prosperous and industrial Baltimore, Maryland in America 1840 when the cookie company moved in)

Victorian prosperity meant… ….Country became Urban. English elite prospered in the reign of Victoria due to development of new machinery, improved work methods, and an underpaid workforce that consisted of adults and children who lived in poverty.

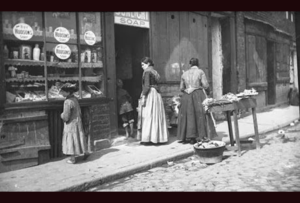

(Photo: 1840 working class on a typical London business district street)

The train in Victoria’s early reign took British to the cities… Many people previously rural became urbanized because they could take the train to town. Country families moved into crowded conditions in towns and cities to stay with relatives while they looked for work. Due to the huge population boom, many lived in poverty without water, sanitation, and sometimes food.

(Photo: poor women of 1850’s London receive baskets of food from the Queen)

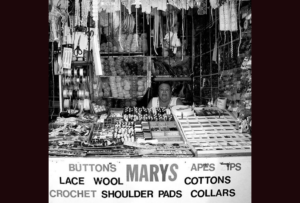

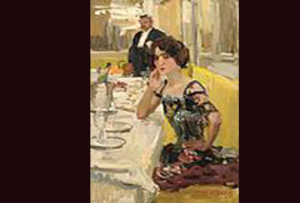

As a result of British society changing, Class structure… …dictated the rules of fashion. Each activity had appropriate apparel for those who could afford it. Those who couldn’t emulated the wealthy with simpler, less structured, and less costly versions of the elite. There was a HUGE industry of clothing resale with peddler carts in special districts for clothing for the working and lower classes.

(photo: London’s tunnels like this under Fleet Street in 1840 were built in the early Victorian era)

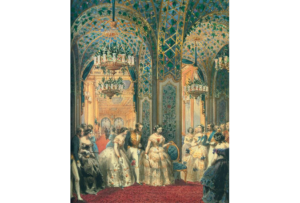

Places like Almack’s and White’s in London… … were highly valued organizations that nobles and elites of London aimed to access. Exclusive “clubs” by invitation only, the London “Seasons” were designed to meet and greet those of similar class status. For men at least, places like White’s were for socializing with entertainment and leisure away from the women. Fashion of the elite was very specifically defined.

(Featured: Almack’s for balls; below White’s for men to gamble, drink, and be ‘manly’)

Queen Victoria of England hosted events… .. like balls – small and large scale for entertainment for royals and elites. Her dictates on clothing were EXACT.

(Sketch: The Devonshire Ballroom in London in 1840 – from the local newspaper introducing its debut)

Britain’s population became urbanized… .. and by 1850, under Queen Victoria, half the country had moved to the cities. Industrial growth and the resulting building boom, and the spread of the railroad combined with a population boom had the character of Britain suddenly changing.

Small towns were overtaken by giant industries. Towns like Crewe which were already on the railroads became “hubs”. “Hubs” met each other to become large joined towns.

By 1870, Britain had grown from 10 million people to 26 million.

Factors of population growth, change in occupation, change in location meant change in culture and economy which would mean – change in fashion.

(Photo: St. James Park, London before industrialization)

New Social Classes emerged in Victoria’s Britain… Improved transportation and the ability to get around meant the English could seek jobs that were not available to them before. While many lived in poverty, others rose in status as the previously defined class structure changed.

Employers moved away from their industrial source of wealth. They bought country estates and were often considered landed gentry. Men without noble ties, previously considered lowly, now rose in status on the basis of their wealth. Some built new streets of houses at the edge of town for their skilled workmen and artisans to live in.

Their key employees and managers built villas outside of town too.

(Painting: Apsley house, the home of the Duke of Wellington as it looked in 1816. Villas and homes like this were no longer reserved for titled gentlemen like the Duke by the 1850’s in Britain)

British class divisions were still apparent… ..in places like church where the higher classes sat in reserved pews, and on trains where they had luxurious cars. Lower classes remained lower classes, but the rising bourgeoisie middle class had an outward display of wealth through clothing and possessions that allowed them to mix in with the high society that was formerly reserved for blooded and titled nobles only.

British wives of industrialists and business owners, dressed in finery “fit for a queen” as they were their husband’s business marketing representatives. It became difficult to distinguish these women from nobility based on how they dressed or behaved.

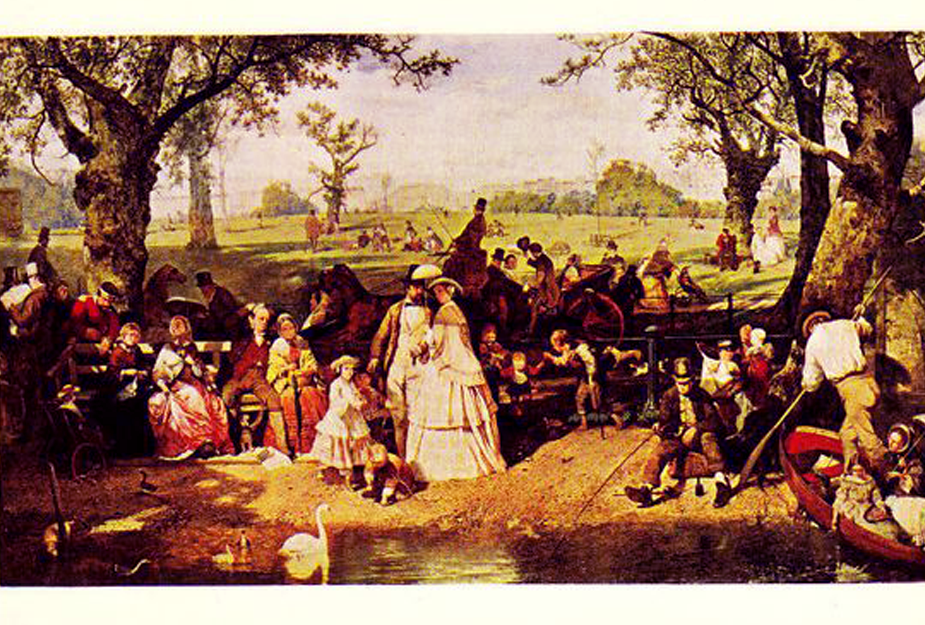

(Painting: by Ritchie, 1858 “A Summer’s Day in Hyde Park” shows the mixing of classes in Britain)

Victorian fashion had everyone dressing like a queen… .. under Victoria, Britain grew, expanded – literally boomed in every way. She was a champion of British technology, arts, sciences, and fashion. In every situation she required, or at the very least, suggested, British goods be used in manufacture of textiles and clothing. The new wealth of the rising middle class of merchants and tradesmen allowed everyone to dress like a queen.

(Portrait: 1840’s “Derby Day” painting by Firth shows the classes mixing at the horse races)

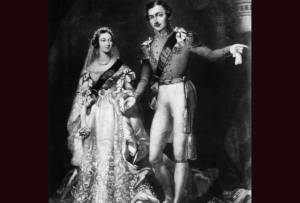

The wedding of Victoria and Albert set fashion trends… Breaking all the previous “rules” of fashion, Victoria insisted on wearing white to her wedding, establishing the “rule” for that activity.. forever. Her dictates from this point on, told all Britains (and so all other countries who were following their lead) what was appropriate to wear on what occasion.

Note: this is just before photography became available. Her early reign is documented in portraits and sketches. Her late reign and her children would be well documented, especially since her daughter Beatrice would become a photographer and have her own dark room.

(In 1840, Queen Victoria was married to Prince Albert)

Queen Victoria ordered guests to wear… .. specific items such as British made lace, or Scottish plaids. She held balls and activities that specifically order the participants to dress a certain way.

(Photo: Victoria’s actual Tartan (plaid) gown worn in 1845)

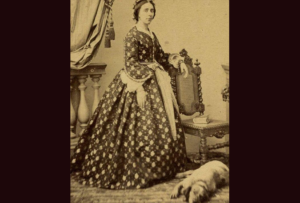

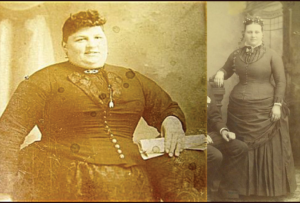

What people wear depends on… … what’s available, accessible, and affordable given the information at hand. As we study the Victorian era and fashion, it is important to understand the many levels and the complexity of the time in many countries. Victoria did set fashion trends, but they were interpreted differently by different women in differing situations.

(Photos of 1889 women at leisure: left – merchant class English woman in walking suit; right – Queen Victoria in a very different and royal kind of mourning/walking suit)

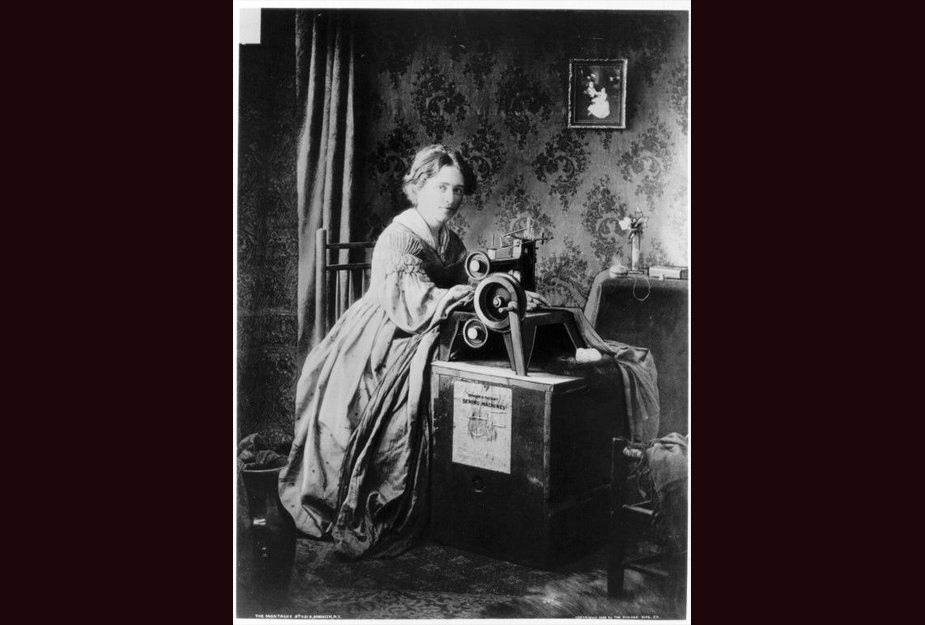

To understand Victorian fashion, you need to understand… …Victorian women. While the houses, streets, and many of the gadgets we use today were just earlier versions of what we have today (pianos, carpet sweepers, sewing machines), the main difference was the place of women in society.

A woman’s place was in the home.

There were of course, independent women with original thoughts, and the expression of that varied with region and country. The Victoria Era spanned 64 years, so it would be wrong to lump everyone as having one same lifestyle. As the era closed, attitudes would shift drastically towards reform in laws pertaining to women, but in general throughout the time, society made life much easier for women if they accepted that a woman’s place was in the home.

Queen Victoria herself changed through the years.

(Photo: Newlyweds Victoria and Albert in 1841)

Women “stayed by the hearth.. whilst men…” … wielded their swords.” (Tennyson). The prevailing attitude of men towards women in the Victorian Era was that all women were weak and helpless fragile and delicate flowers incapable of making decisions beyond selecting the menu and children were taught moral values.

A gentlewoman ensured that the home was a place of comfort for her husband and family from the stresses of Industrial Britain.

“(A wife’s) prime use is to bear a large family and maintain a smooth family atmosphere where a man need not bother himself about domestic matters so he can get on with the making of money.” (“Beeton’s Book of Household Management“)

(Photo: in the 1840’s, young women were taught to let the man win in a game of chess)

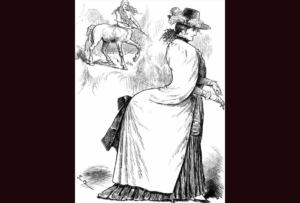

The objective of the “proper” Victorian woman was… …marriage. Girls were groomed like racehorses in preparation for that, making sure she could sing, play an instrument, speak foreign languages, and above all be innocent, virtuous, biddable, dutiful, and ignorant of all intellectual opinion.

(Colorized photo: Dating in 1860’s upper Manhatten, USA)

Victorian wives were required to be faithful… .. even though husbands kept mistresses, and were free to mingle in their “gentlemen’s clubs” where they could find a warm welcome among male friends, and often comfort in a woman’s.

If a women took a lover it was never to be made public because if it did become public knowledge she would be cut by society. If she divorced, she would have zero chance of acceptance in society again, although men easily moved on to the next relationship.

As a result, it was a time where relationships were quite artificial, for upper and merchant classes at least.

Until 1887 a woman could not own property, and even that which she inherited from family was turned over to her husband the day of their marriage. She herself was “owned” by her husband. In 1887 the Married Woman’s Property Act gave English women rights to her own property.

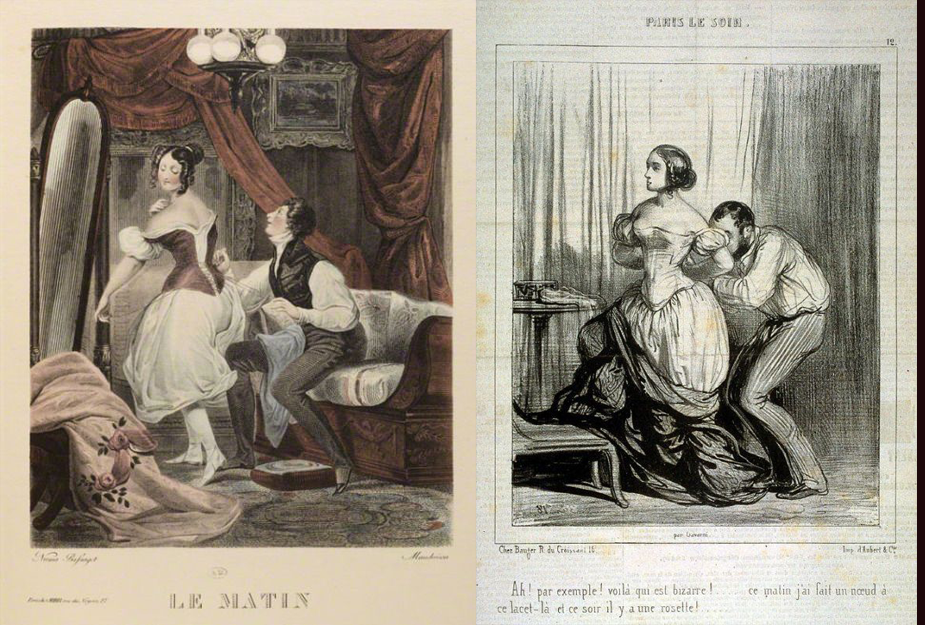

(Painting: Flirting in a Parisienne Salon in the 1880’s)

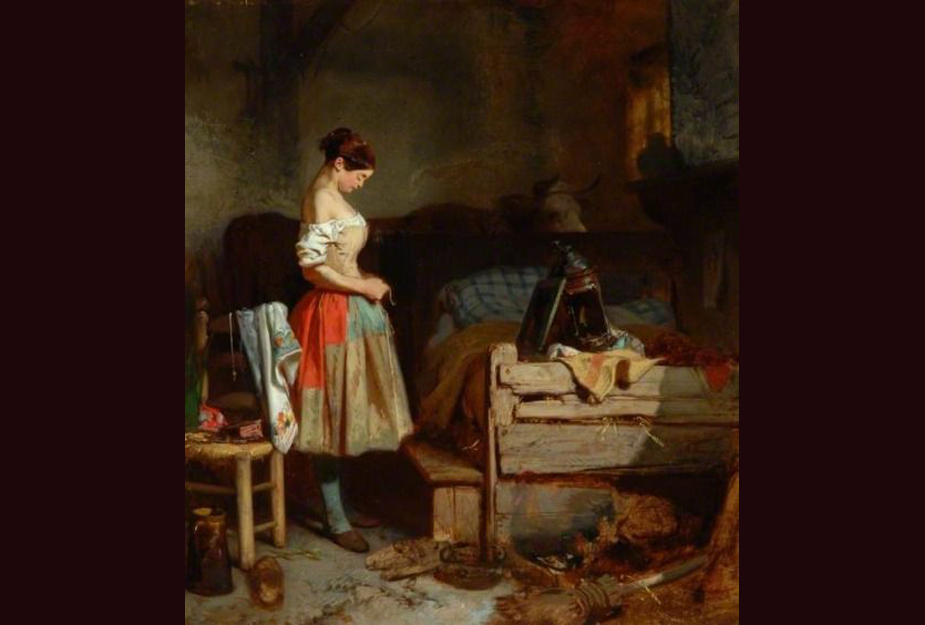

Life for wealthy vs poor Victorian women of Britain… … was very different. An affluent wife was supposed to spend her time reading, sewing, receiving guests, going visiting, letter writing, seeing to the servants, and dressing the part of her husband’s social representative.

Her clothing was made specifically to show off wealth, and that became more and more lavish as the 1800’s progressed until rich women’s outfits literally “dripped” with lace, beads, ribbons, and bows. She had up to 6 wardrobe changes a day which changed over 3 seasons a year.

In contrast the very poor wife of Britain wore clothing handed down and remade, typically “5th hand”. They ate food leftovers from rich households, and what they bought was often inferior stringy meat, old bread, cheese, herring, porridge, or kippers.

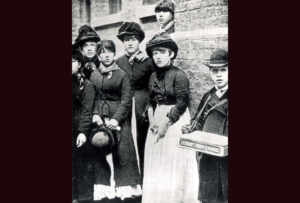

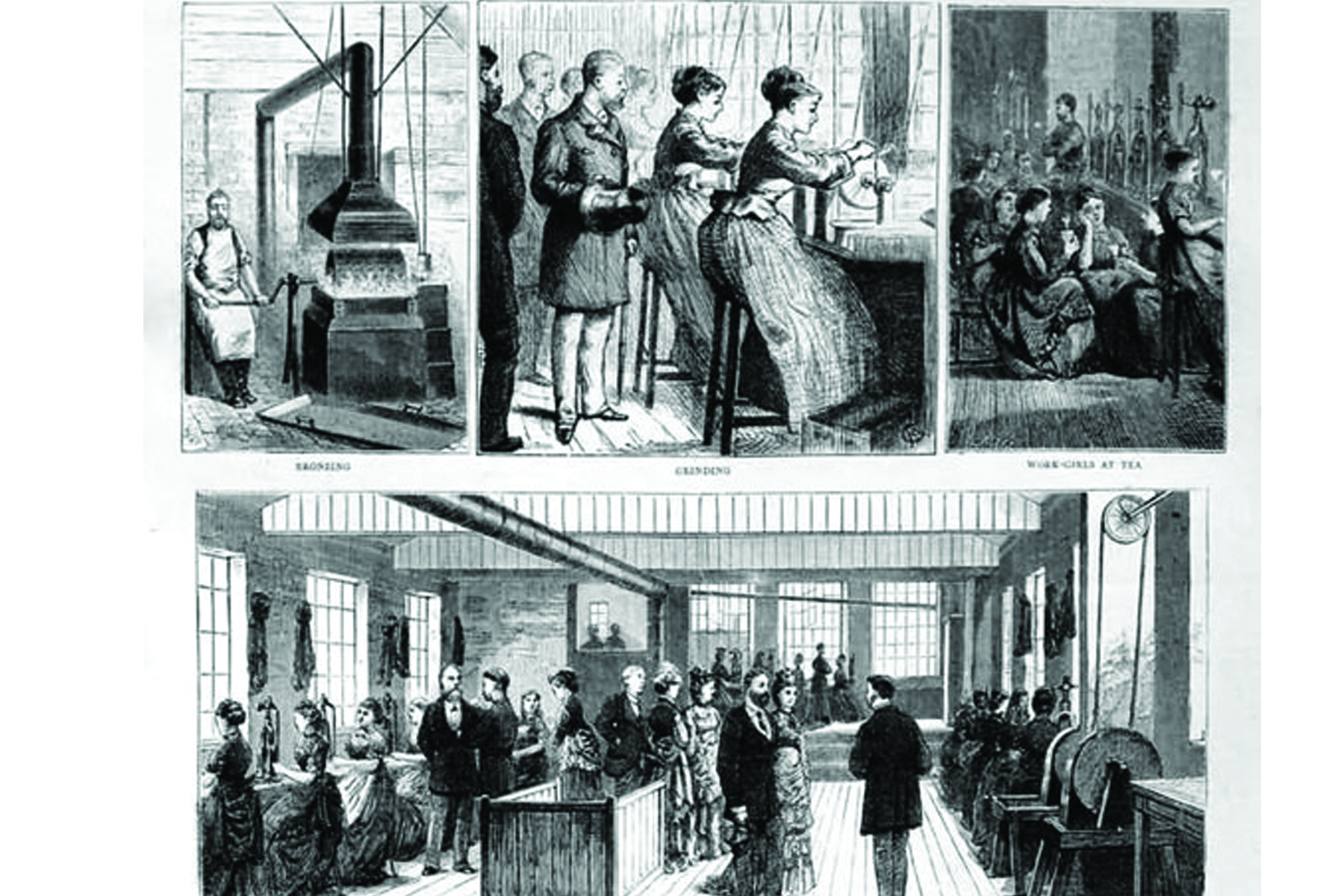

(Photo: 1880’s Bryant May mill workers; working lower class women of London)

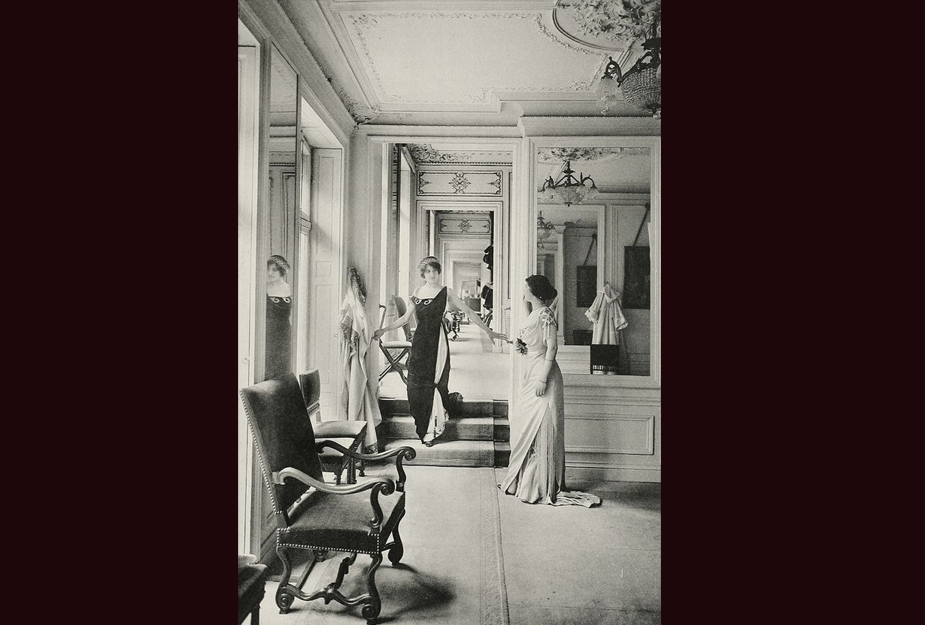

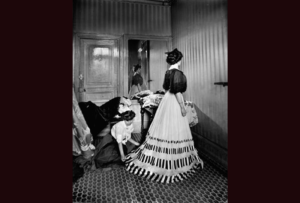

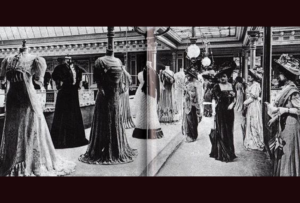

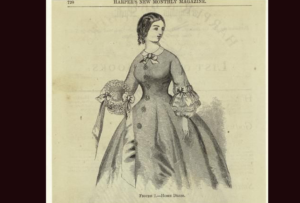

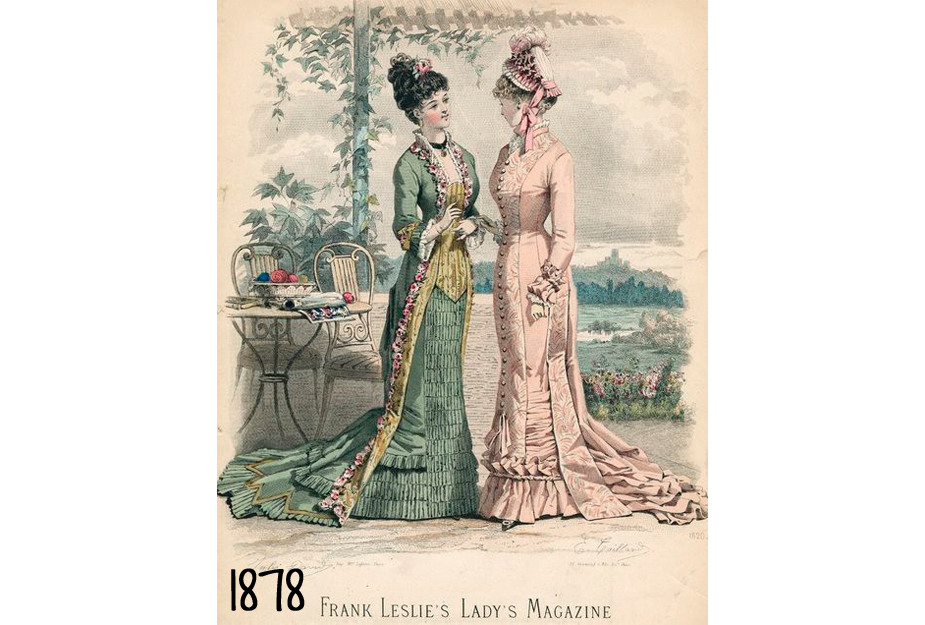

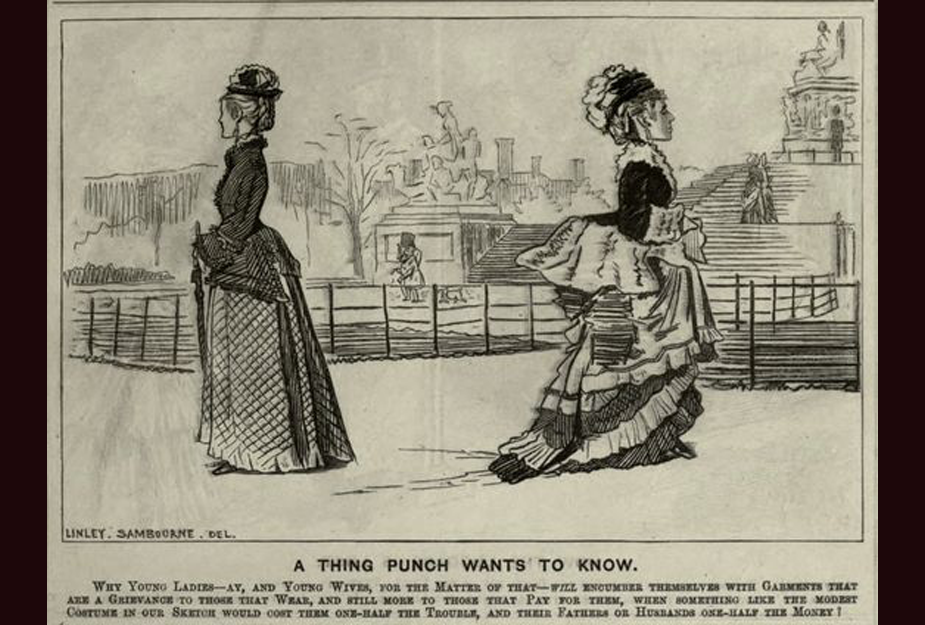

For wealthy, noble, and elite Victorian women.. … Victorian fashion required different ensembles for different occasions. Designer Charles Worth, an Englishman-turned-Parisian-designer, introduced the word “costume” at this time, and Victoria expanded upon the concept for her country.

“Costume” meant there was morning and mourning dress, walking dress, town dress, visiting dress, receiving visitors dress, traveling dress, shooting dress, golf dress, seaside dress, races dress, concert dress, opera dress, dinner and ball dress.

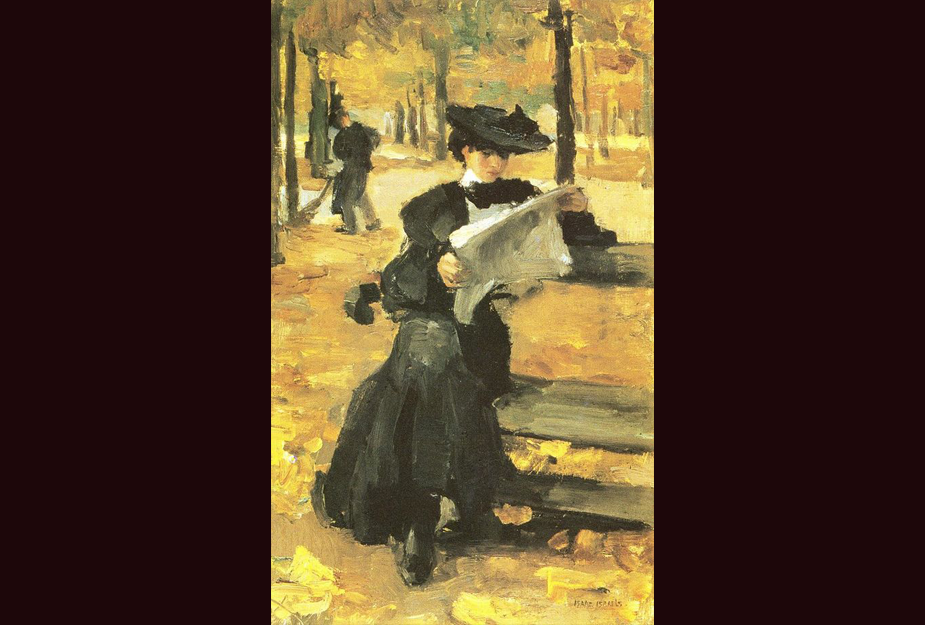

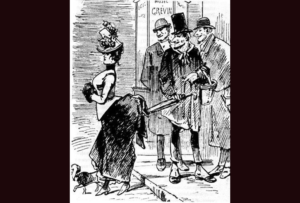

Fashion plates were hugely successful in this era giving ladies supposed to women visual clues on how to dress for their new found status. New activities were invented just to show off status through “costume”, such as parading around city parks in carriages.

(Sketch: a typical 1868 Victorian fashion plate which shows women how to dress in Costume)

Change in Victoria’s Britain was happening… …everywhere and at all social and class levels. New inventions and how to use them opened doors for poor women to improve their situations through work. Acceptance of women as thinking beings as the era progressed closed the gap to give women common causes to rally around. The place men and women were equal was in the use of new “gadgets’, because no one could figure them out. The dynamics of men and women, and poor and wealthy, changed as the Victorian Era progresses.

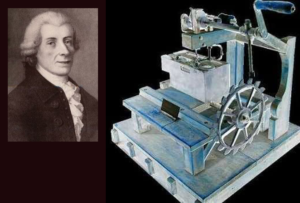

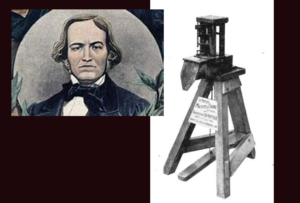

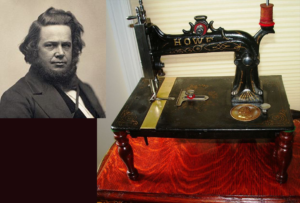

By 1900 the railway, typewriter, telephones, post, camera, sewing machine, synthetic fabric fibers, and the bicycle became used in every day life. Women became secretaries, operators, and opened their own shops.

The Tailor Made Garment movement had women designing, making, and selling garments, as well as wearing them to work outside the home. The industry gave them credibility and confidence outside being just an asset to a husband.

(Photo: Mary’s Haberdashery in London started in the 1880’s and was still in business well into the 1980’s)

Reform for women happened through the Victorian Era… … as Victorians began to recognize women as thinking people. As the year 1900 approached, women intellectuals began to speak openly. Many joined the Fabian Society, a group of socialists. Others sought reform for more practical dress (e.g. no corsets), better education, the right to keep their profits from paid work for themselves, better employment prospects, and better pay for women.

Most notoriously, women began the campaign in Britain that would lead thinking women around the world to have the right to vote and for birth control. The Victorian Era would be known for beginning the women’s rights movement worldwide.

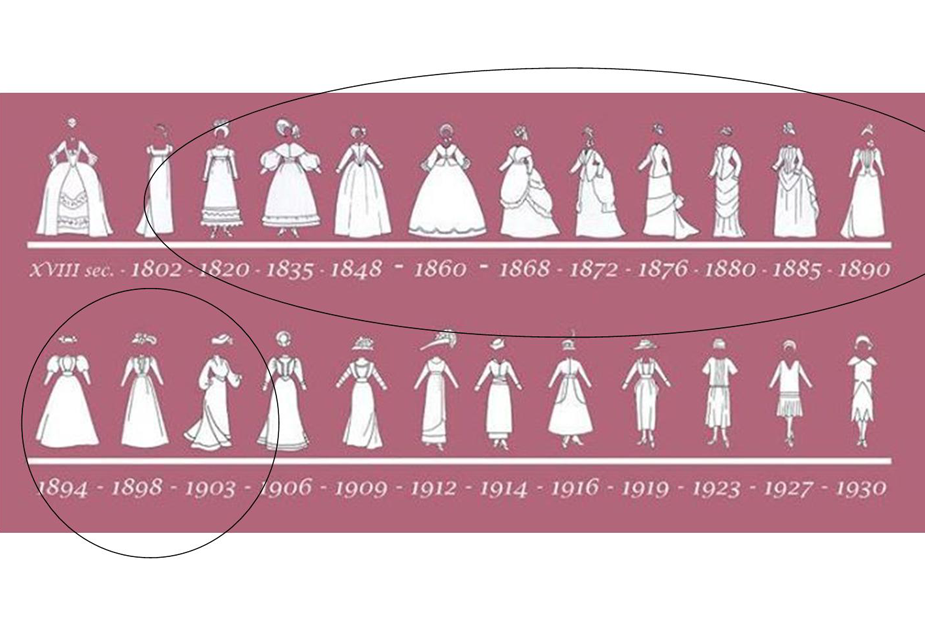

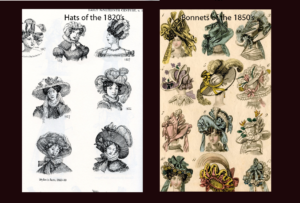

Historians break Victorian fashion into eras… … and there were many as Queen Victoria reigned from 1837 to 1901. In the beginning, most fashions lasted about a decade, but by the mid 1850’s, mass communication and mass production had improved so much that by 1901 the history of fashion was moving in almost a yearly cycle.

Silhouettes breaks down the eras into six using key features like bustles, crinolines, and sleeves into “early,””mid”,”late”, and “pre-Edwardian.

There were actually many, many more subcategories and countermovements such as aesthetic and reform dress in those years (as per sketch featured).

The 1st Victorian Fashion Era was… …considered by historians to be Queen Victoria of England’s early reign, 1837-1860. In this time she was a teen, was crowned, was married, and had all of her children.

The 1st Victorian Fashion Era was… …considered by historians to be Queen Victoria of England’s early reign, 1837-1860. In this time she was a teen, was crowned, was married, and had all of her children.

Victorians in the United States

Why would Americans care what an English Queen thinks?

In 1837 when Victoria was crowned Queen of England, American independence from England was only 54 years old. Most people in America had a family member or some connection to the War and England in some way. In that same time, England had gone through 3 King Georges and the (English) “Regency” period, Napoleon had risen and fallen, and the Bourbon lineage was back on the French throne.

Trade was abundant between a thriving United States that could provide raw goods to those war torn countries of Europe who continued to fight amongst themselves (the French and English notably). Americans were reaping the benefits of inexpensive finished goods from Europe and European worldwide colonies, and now that the Asias had opened up to trade, American women had a lot of choices whom to follow and how.

Most chose England.

(Portraits: 3 key fashion influencers 1783 (official end of Revolutionary War) to 1837 (start of Victorian era): left to right – Marie Antionette married to Louis XVI a Bourbon, Josephine Napoleon’s 2nd wife, and Victoria in about the 1860’s the prime of her career).

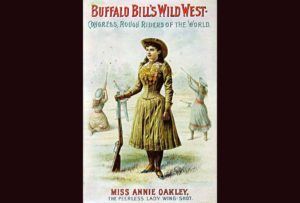

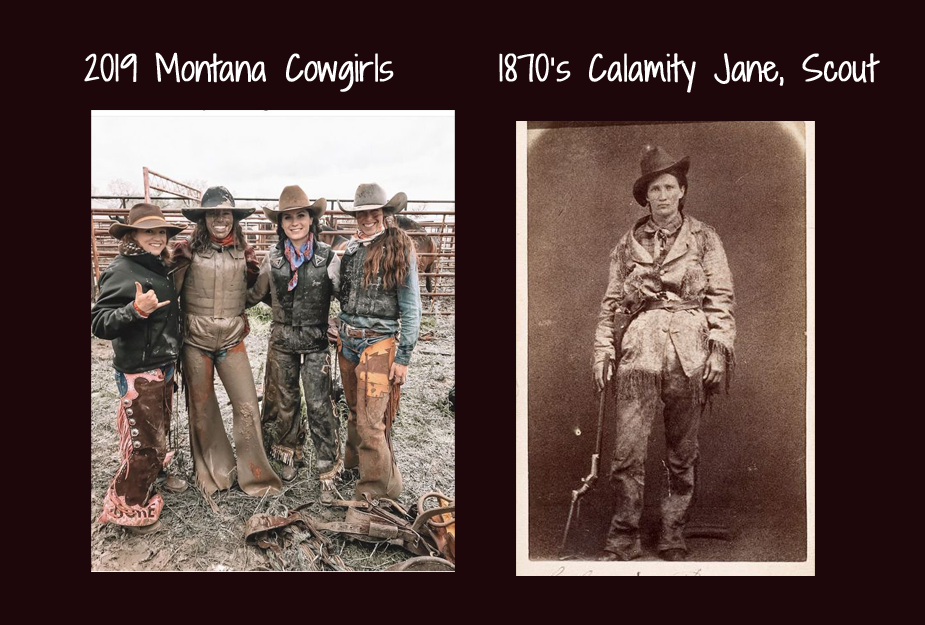

By the end of the Victorian Era, England would.. … become so enamored with the American spirit, the casual and less structured lifestyle of Americans, and particularly the romantic American West, that the English and Europeans would start to “peek” at American women to set the fashion trends.

Stories of Daniel Boone at the turn of the 18th into 19th centuries had awakened the curiosity of the English in particular, and in about 1900, with Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West show coming to England to show first hand what those legends were talking about, the influence would switch.

In 1837, however, it was Victoria who was running the worldwide fashion show.

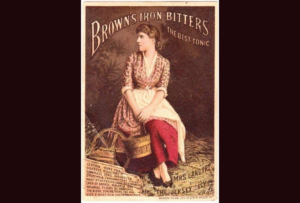

(Poster: Annie Oakley was always in the height of fashion (in her Victorian corset); here photographed for marketing advertising Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show which would perform in England around 1885 that year)

Victorian England had class disparity… … as we discussed in detail earlier this summer. There were those of rich and noble blood, and then there were poor. BUT, as was happening in America, there was a rising middle class made of merchants, industrialists, and financiers.

They walked among the previously “taboo” royal or noble elite – men we are talking about of course in 1837. The women associated with this middle class were mostly the social advocates for their men.

Fashion for a middle class Victorian woman was a status symbol, and much discussion in all worlds was about “pecuniary emulation” (translated – “showing off your stuff”).

(Photo: Afternoon Tea in New South Wales 1890. Settlers moved to towns created by industrialists and developed a whole new middle class structure while hob nobbing alongside blue-blooded nobility)

Victorians had gender disparity too… Although women over the 1837-1901 period made HUGE gains, each country was slow in progress towards women’s right to vote, elimination of slavery, marriage and ownership laws, and equality in the work place.

Under Queen Victoria, England was the first among Europeans (Scandanavians), and Americans to abolish slavery, give the right to vote, and give women the right to own property. The Scandanavians (Holland in particular) were the first to have women in higher education and to have the first medical professionals and scientists.

American women and blacks would not get the right to vote until well after the era, and while they could work, play sports, and run businesses, they were still assigned specific societal roles with limitations throughout the era.

(Photo: a Russian man and his wife illustrate gender disparity in 1900)

Not Everyone in Europe Followed the Queen

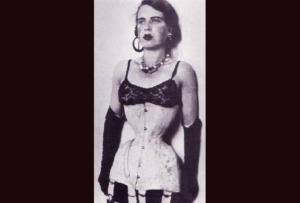

In the industrial and technical world of this time frame, movements like the Rational Dress Reform Society and the Aesthetic Dress Movement arose in reaction to what was going on economically and socially.

(Photo: Bloomers were introduced to society in 1855 by the Reform Movement, but were only worn by women in insane asylums)

The Rational Dress Movement

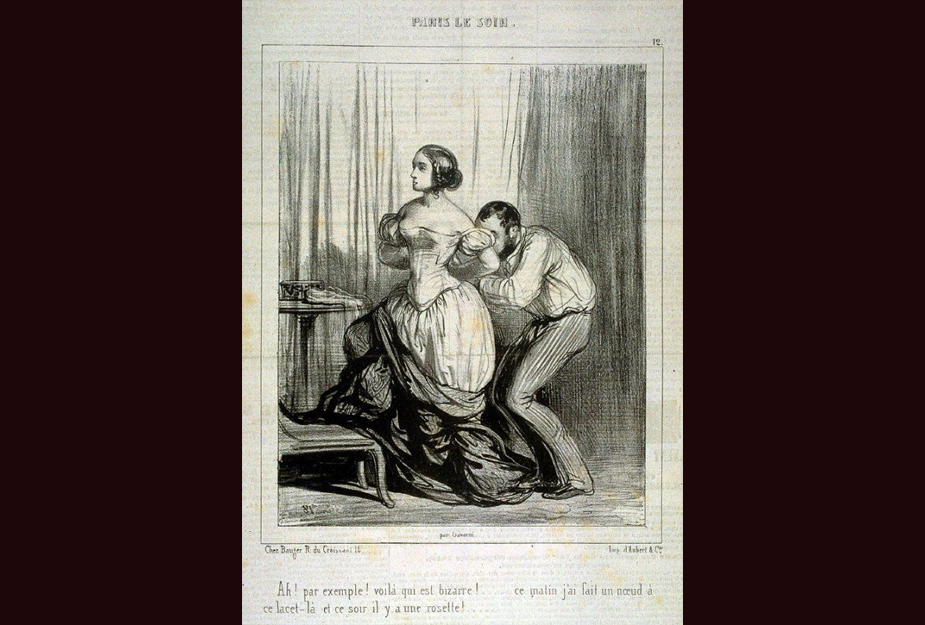

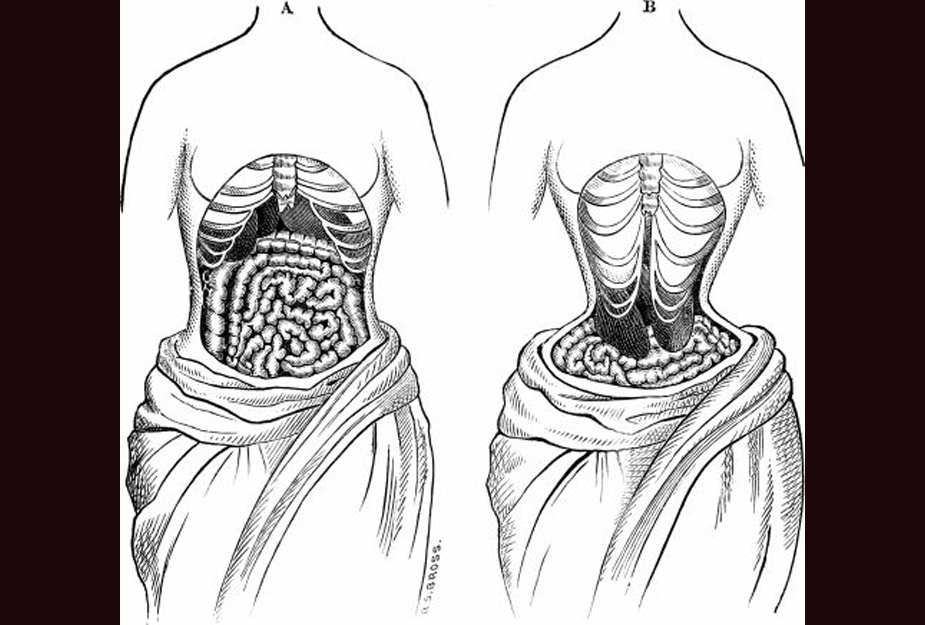

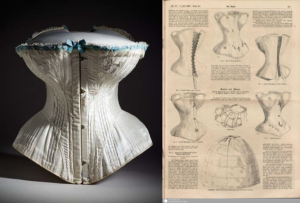

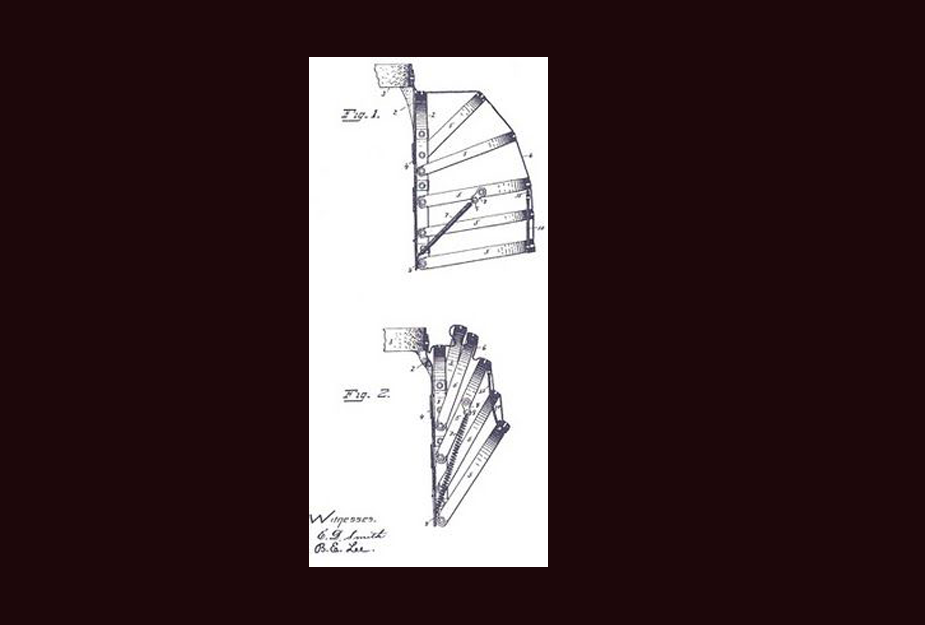

The Rational Dress Movement during the Victorian era also introduced… … soft and comfortable corsets, approved by physicians. The concept of wearing something other than highly “trussed”, constricted style that had been in vogue since the invention of metal grommets in 1822, was indeed challenged by many throughout history, yet few women embraced the idea.

The position of a woman in society in the Victorian Era was reflected by dress. Anything less than the prevailing silhouette was considered vulgar and demeaning by most women.

(Photos: Left – 1890 Gibson Girl the ideal of that day was very constricted and shaped vs Right – the wife of Reform Movement leader in her Reform (corsetless) gown in 1903)

Aesthetics & Pre-Raphaelites

The Aesthetic Fashion Movement came out of… .. the Reform Movement. Aesthetes saw fashion as ugly machine made products from the Industrial Revolution. Their dislike ranged from distaste for the ugliness of false structures and veneers to the crudeness of synthetic dyes to the over working of Victorian imagery.

They ignored the benefits of cheap costs for mass produced goods for those of low income or those who wanted to imitate upper classes on a lower budget.

(Portrait: Mrs. Frances Leyland in Aesthetic dress about 1874)

Aesthetes hated sewing machines… … because it allowed excessive embellishment of dresses because trims were so cheap with mass production and because trimming could easily be added at home or in the shop.

(Photo: a family of Aesthetes in full Aesthetic fashion in about 1900)

Aesthetes were dangerous to vegetables… The Aesthetic (“counter fashion”) movement within and counter to the Victorian fashion era went beyond textiles and fashion. Aesthetes were also often vegetarians and campaigned for animal welfare rights.

They objected to the use of feathers on hats and the use of whole dead birds as a hat ornament. Modern vegetarianism has its roots in this movement.

(Photos: 1897 Aesthetic tea gowns. They loved this carrot orange color!)

The Aesthetic movement was technically 1870-1880… … in the mid-Victorian Era, although it got its start in reform and the early eras and in response to industrialization and mass production. They were a group of talented artists, poets, writers, and actors.

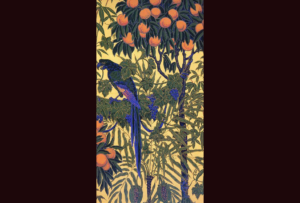

The leader was painter William Morris. He and architect Voysey designed houses together being fastidious about every detail from wallpaper to furniture, to window and fireplace proportions. Morris designed textiles and embroideries which he produced through his company Morris and Co.

Many of his original flowing organic designs are still used today, although the colors are adjusted to suit modern tastes.

(Fashion Plate: late 1880’s-90’s Aesthetic gown like Morris’)

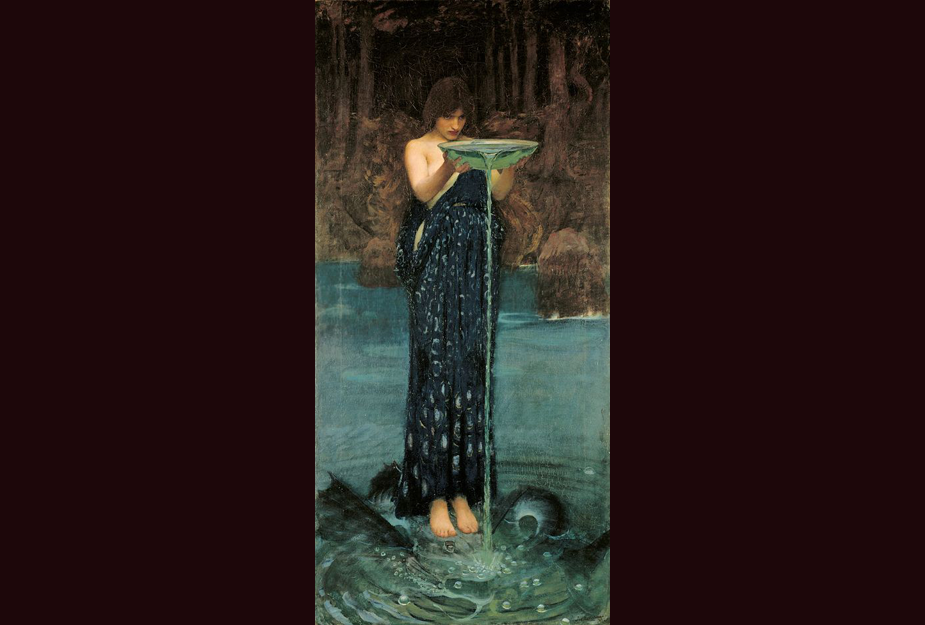

Paintings were the inspiration for Aesthetes… …as they were influenced by the Pre-Raphaelite paintings of Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Edward Burne Jones who idealized medieval life in imaginary ethereal scenes. The women in these paintings appear to wear no corsetry and have freedom and “naturalness” that was admired by the Aesthetes.

(Featured: painting by Pre-Raphaelite leader J.W. Waterhouse “Hylas and Nymph”)

(Below: painting inspiration by Aesthetic for gown)

Pre-Raphaelites who inspired Aesthetes were artists… .. in the 19th century who despised the “schooled” method of art that was prevalent in the day which required certain lighting, levels or realism, and specific rules. Pre-Raphaelite art was often erotic, sensual, and depicted women scantily clad in dreamlike settings with mythological themes.

The Aesthetic counter-Victorian fashion movement embraced the Pre-Raphaelite concepts of wanting to show the beautiful, natural, and organic forms of the body, plants, animals, and the world around them.

(Painting: “Circe Poisoning the Sea” by JW Waterhouse, Pre-Raphaelite movement leader. Mythological themes, beautiful sensuous women, idyllic settings, and many plants and organic forms are the hallmarks of Pre-Raphaelite art)

Pre-Raphaelites, Aesthetes, & Reformers… .. the counter design movements to the Victorian eras – the Pre-Raphaelites preceding and inspiring the Aesthetes, and the Reformers building on those concepts – took place worldwide, and predominantly in Europe.

As would be the Art Nouveau fashion movement in 1900, forms and styles were regional, meaning Prussia might have different interpretations than England or France of the same Aesthetic concept. Germany had a very strong Aesthetic influence.

(Photo: German Aesthetic tea gown of 1900)

Aesthetics did not limit themselves to fashion… … or fabrics. TheAesthetic movement within the Victorian fashion era were big in the development of interior design elements and architecture.

(Photo: The Green Room in the Albert and Victoria Museum in London, was designed by William Morris, a leader of the Pre-Raphaelite movement, and inspiration for Aesthetes)

Wallpaper, stained glass, and other highly crafted… … interior and exterior designs as well as beautiful fabrics were the Aesthetic Movement’s contribution to Victorian society.

(Photo: an Aesthetic wallpaper and stained glass interior from about 1900)

Counter Victorian fashion movement Aesthetes felt women needed to look more like… … the nymphs and sensual creatures of art. To blend and suit these surroundings it was felt that some reform in style of dress was needed. Among artistic people the resulting fashion was known as Aesthetic dress.

(Photo featured : 1900 approx. Aesthetic Tea Gown has the Victorian model looking like J.W. Waterhouse’s Pre-Raphaelite paintings below)

Pre-Raphaelite Waterhouse vs Aesthetic… .. paintings vs. how the Victorian counter-fashion movement the “Aesthetes” interpreted them. The Aesthetes, like the Pre-Raphaelite painter J.W. Waterhouse, looked for sensuous beauty, organic forms, flowing movement, mythological and ancient themes, and rich colors and textures with amazing fabrics and highly crafted trims and details.

The Aesthetic gowns of the Victorian era were deceptively complex in their draping and ornament so as to be beautiful and comfortable.

(Left: Aesthetic day dress vs. JW Waterhouse painting right)

More Victorian Era Aesthetic Gowns vs. Pre-Raphaelite.. .. paintings. Both gorgeous depictions of rich fabric and ornament, flowing movement, and lovely colors. The Aesthetics wanted the women who wore these to be comfortable, sensuous, and to have the adventures of the J.W. Waterhouse depictions.

(Left: 1909 Aesthetic gown; Right: J.W. Waterhouse “The Knighting”)

Yet another idealized painting vs real Aesthete dress.. .. does capture the spirit, attention to detail with intricate trim, and flowing fabrics and colors of the Pre-Raphaelites. The Aesthetic concept of draping and fabric is still used today in bridal, formal wear, and costuming such as CosPlay.

(Featured left: 1900’s Aesthetic velvet gown vs. J.W. Waterhouse Pre-Raphaelite painting “The Crystal Ball”)

One more Aesthetic vs Waterhouse painting… .. this being part of Pre-Raphaelite J.W. Waterhouse’s “Ophelia” series, and a favorite inspiration for the Victorian era Aesthetic gown designers.

(Photo left: 1909 tea gown; Right: “Ophelia”)

The “counter” Victorian fashion movement, Aesthetics. These were artisans, craftsmen, and designers committed to maintaining the highest quality of fabric, texture, line, and design in response to what they felt was “crass” mass production.

Getting their concepts from the “Pre-Raphaelites” who were a “rebellious” artistic movement (“Pre-Raphaelites” were protesting the formula type of art where light, composition, subject, and content were dictated by strict rules – thus wanting to go back in time before the “Raphaelites” who made all the rules came into power in the art world), the Aesthetics used the “Pre-Raphaelite concepts of eroticism, mysticism, mythological themes combined with artistic draping and fabulous colors, organic forms, fabrics, and notions to build what looked very much like the Pre-Raphaelite paintings. Their influence would blend and merge with “Art Nouveau” .

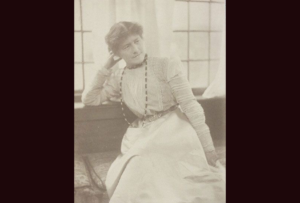

A key Aesthetic rule was that there were to be NO CORSETS, and NO UNDERSTRUCTURES. They felt the forms and messages would convey enough. A few women embraced their designs, but most of the Aesthetic models and real life customers were considered quite radical for the time.

(Photos: left – Violet Lindsay; right – Jane Morris (wife of the founder) – both about 1894 in Aesthetic Dress. They were the key champions for the cause, and don’t they look happy)

Aesthetic fashion imagery extended to the home.. .. in stained glass, wallpaper, carpeting, and design. Differing from the “busy” Victorian household, the Aesthetes aimed for balance and comfort, and although not knowing the concept yet, a type of “feng shui” in the flow and dynamics of house, home, and costume.

(Photo: an Aesthetic stained glass from the early 1900’s. Note the same imagery as the Waterhouse paintings is used, and how familiar the organic imagery is to the Art Nouveau which was being developed at the same time)

Aesthetic customers were not “poor” or “radical”… .. many wealthy women, and particularly English and American women, could afford to be what was considered “on the fringe” of fashion by wearing Aesthetic clothing. The obvious difference between Aesthetic gowns and high fashion of the day was a distinct lack of corset. Second notorious feature were flowing and mythical draping; 3rd the gorgeous fabrics and textures.

As with all Victorian culture, the wife of a rising merchantman was his marketing agent. She had to dress to impress.

(Photos: Rosamund Hussey, wealthy woman from Kent, proudly marketed for the Aesthetes to try to get her peers to embrace the fashion movement)

The sensuous image the Aesthetes were trying to present.. .. sometimes fell a little short of the ideal that was presented by Pre-Raphaelite paintings. The result of “natural and beautiful forms” sometimes resulted in frizzy hair, poor draping, or strange accessorizing. You have to give them credit for trying as they believed every woman was beautiful and sensuous if stripped away all the artifices of fashion. Unfortunately, not every woman could look like a Waterhouse painting in her “natural” form.

(Left: Waterhouse portrait of the ideal woman vs. a real 1900 Aesthete trying to look sensuous on a humid day with naturally curly hair)

Aesthetic fashion is here today… .. you can find the concepts of mythological figures, lack of corsetry, emphasis on the “natural” shape of the female body, flowing and organic forms, colors of nature, and attention to detail, draping, and ease in movement in today’s bridal wear.

The main difference is that today synthetic fabrics and notions are prevalent to keep the cost down and to enable mass production, as often the gowns are worn for a single event. The problem is, the modern wearer will have no concept of the comfort of the 1900 natural and breathable fabrics as they sweat down the aisle in their polyester replications.

(Photos: left: “We are Stardust” at a bridal and formal wear fashion show; right: bridesmaids dresses for sale on Etsy)

Gorgeous Aesthetic gowns took gorgeous fabrics… … and Liberty of London’s was THE place to buy. Not only did they create original, high quality, natural fabrics with dyes and prints specific to the Aesthetic cause, but they provided key fashion designers. It was Liberty’s that brought the Aesthetic dream of fashion to life.

(Left: Pre-Raphaelite inspiration “Lady of Shalot” and right: “Mariana in the South” embrace a Liberty of London silk Aesthetic tea gown from about 1900)

Victorian era Liberty of London fabrics… … sold to high fashion as well as Aesthetics. They catered to those wanting fine quality textiles and trims like these tea gowns are made of. The carrot orange is seen often in early 20th century gowns. Today Liberty adjusts colors and designs to suit modern tastes.

(Photo: Liberty gowns vs. JW Waterhouse Pre-Raphaelite painting)

Today’s Liberty of London… … sells cosmetics, home furnishings, textiles, custom design, household objects, and other toiletries in addition to providing fashion design and oodles and oodles of fabrics. The current price of a “Tana Lawn”, which is considered “traditional printed cotton” for them, is about 23 British pounds, or about $40 US after shipping from the store in Carnaby, London.

(Photo: The Liberty of London store front 2018)

Liberty of London fashion design today.. .. still has a lot of the Victorian Era “Aesthetics”… comfortable, rich, luxurious.. and there are certainly no corsets! Today’s imagery, however, is specifically designed to appeal to modern buyers.

Liberty of London still makes beautiful.. .. fabrics and apparel; suited to modern tastes.

Leaders of the Aesthetic movement were largely.. … the wives and daughters of male Aesthetic artists and designers.

(Photos: left Violet Lindsay; right Jane Morris in about 1894 were leaders in the Aesthetic design movement, and German models)

Aesthetics marketed to the public… .. using photographs and settings as picturesque as the images they were trying to create with the garments.