Leine, Brat, & Airisaidhs

Celtic Fashion before the 18th Century

For a long time Colonial fashion was influenced by the Dutch early settlers, and the British. Only the cloth was ALL British, not the items.

In Scotland, in conflict with the English and allied with the French, it is assumed the same thing occured for the Scots – both at home in Highlands and abroad in the Colonies.

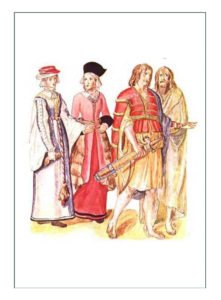

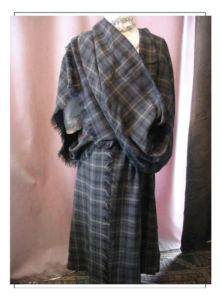

The “arisaid” was a great kilt for women for centuries in Scotland. It used 9 years of fabric. A “Leine” (pronounced ‘Lay’ na) was the original garment of the Gael – the ancestors of the Scots and Irish. Roughly translated, it was a “shirt” or “tunic” and while not much more was worn with a leine, it was not an undergarment.

With increasing contact with the Irish through the years. in the 5th and 6th centuries they found common ground in what they wore. There was at that time a 2nd basic manly garment added: the close fitting smock or over mantle called a “brat”. The leine “shirt” was pulled up through armholes.

In 1550 Irish men wore long tunics with wide hanging sleeves called “ionar”. These were belted at the waist and drawn up so the hem ended up at the knees and made a slack above the waist that worked as a giant pocket.

These were dyed with saffron to a yellow.

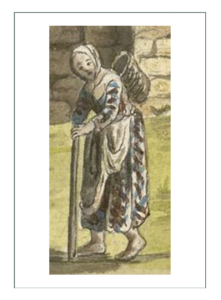

The leine evolved into a shortened skirt like garment which was pleated rather than “bagged” around the waist. Women wore these things too, but to mid-calf not above the knee. Some wore an open front that wrapped around the arms with full sleeves like a loose jacket.

By the 16th century most Leine, Brat, and Ionar were made of linen that was very thick and woven by hand. Some had silk, but that was rare. Saffron was grown in Ireland, so was easy to obtain and use.

When King Magnus of Scotland traveled, he adjusted the wearing of the tunic and “deconstructed” it into a form closer to the kilt and plaid we see today. The new tunic was called “kyrtlu” and the upper garment a “yfir hafnir”: basically still the leine and brat.

This ensemble was criticized by the “fashionable French” in 1556 as “only wearing some sort of light woven rug, barely covering the knees”.

After 1600, the style was anglicized (made more English) again, so the leine became more of a loosely fitted shirt. They were still always yellowish, buff, oatmeal, cream or brown/yellos in color. a Brat might be anything from plain to a colorful stripe, check, or tartan.

The Highland clan kilt actually started in the 1700’s, much to the dismay of the English.

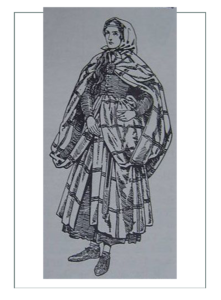

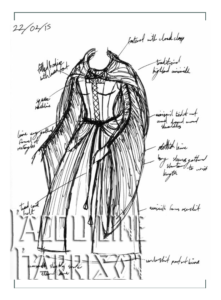

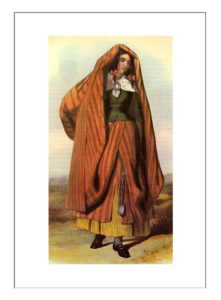

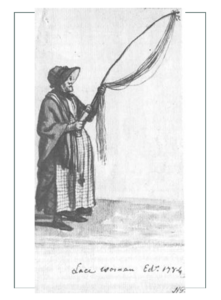

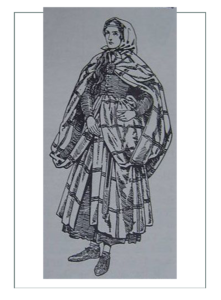

In the Lowlands they wore closer to what the French and English were wearing; especially the women. Highland women did adapt European fashion, but basically they wore a version of leine and brat. They wore their brat as a shawl wrapped over the shoulder, or up and over the head. No matter how they were worn, or what they were made of, a woman’s outer garment was called an “airisaidh”.

A bodice with many varieties was called a “weskit”, and a seamless cape a “ruann”.

Celtic Fashion in the 18th Century

The Highlands were considered the “backwaters” of Europe.

Prior to the 17th century (1600’s) Scots and Irish wore much the same thing, but there is very little information about what “that” was they wore. It is documented that in the 17th century the Irish began to wear similar fashion to that of their near neighbors, the English peasantry. The Lowlanders joined them, as they were tied more politically and economically to both Ireland and England.

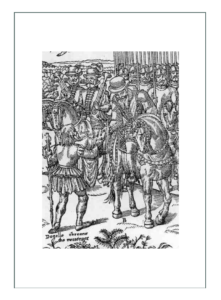

The Highlanders kept their traditional dress, the bonnet and plaid, which had actually originated in concept in the Lowlands. They had developed their own forms of them.

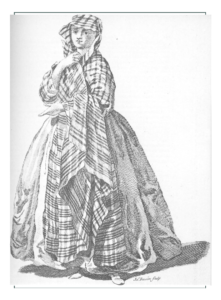

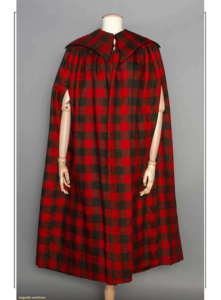

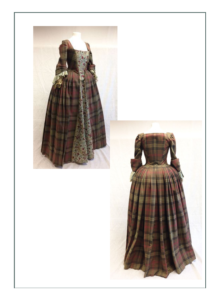

Checkered cloth in particular was worn throughout history in all the Celtic cultures. In the beginning they were simple 2 colors and symmetrical weaves. In the 18th century these were refined and developed by the Highlanders from the 17th century models.

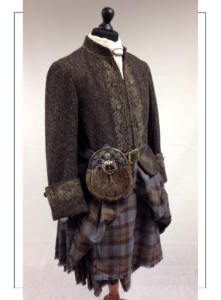

Elements of all European fashion were seen in both the Lowlands and the Highlands entering the 18th century. Notably these were jackets and the styling of them (“waistcoats”) for men and the knee length breeches worn around the world at the time. The Highlanders maintained their distance by continuing to wear their ballock knives and sporan along with European dress.

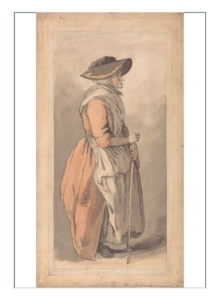

Men still wore the “Leine”, but it did NOT lace up the front as re-enactors tend to believe today. They also wore the “Brat”, or a cloak, and they also wore “Trews”, jacket, and shoes much as they had for the prior century.

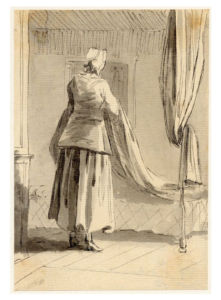

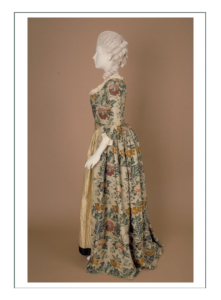

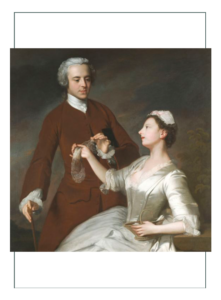

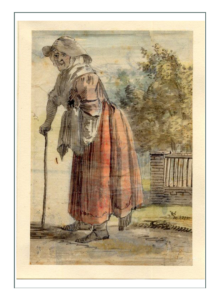

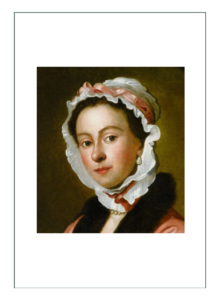

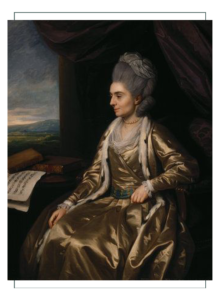

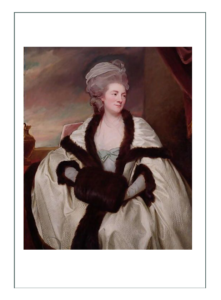

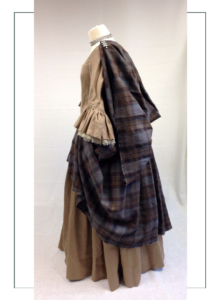

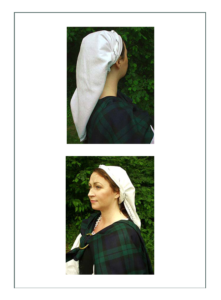

Due to lack of evidence, and using extant models and portraiture as a guide, it is assumed by historians women wore the same as other women throughout the British Isles in the 18th century: a shift (“Sark”), similar in construction to the English. They wore several ‘petticoats’, and “Arisaid” (the women’s form of the Plaid), stays, a jacket or bedgown, plus a head-covering “Kertch” if married. Single women left their heads uncovered.

Plaids & Tartans

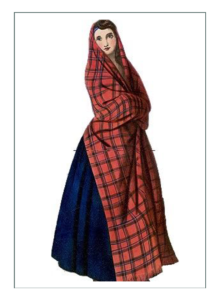

Plaid (pronounced ‘play d’) means blanket or cloak, and not a pattern or a weave. It can refer to a striped or simple check. “Tartan” is the term for the pattern or design; the weave within a “plaid”.

For a man, a plaid is and was 12-18′ long by 5′ wide, made of 2 strips of cloth sewn on the long ends, with fabric being 30″ wide. Today they can be made with one length of our wider 60″wide fabrics.

Those who could afford colorful and many different patterns did. Most people had “earth colors” in browns and naturals like greens, tans, and grays. They had other dyes including the bright “saffron” yellows of the stays and ancestor “leines”, but they took regional pride in wearing a color or type of weave that indicated their geographic alliances. Stripes and solid fabrics were common.

In the early part of the century, men and women wore mantles, which were capelets made of sheep or goat skins with or without the hair. They were thrown over the shoulders for warmth.

When the Clan Tartan was allowed to be worn again in the early 1800’s, Tartans were regionally woven much according to Clan lines. Sometimes people mixed in many Tartans in one ensemble; notably the lairds were quite colorful.

Women’s plaids, worn as the “arisaid”, were about the same as the men, but smaller so they would not be buried in the fabric. Theirs were often plain white or small striped with a much finer weave, more lively colors when they had them, and the woven squares of a pattern larger than the men’s.

Outerwear was the same as English women wore; a jacket like the men’s, but short to accommodate plaids and belting. Women never wore the waistcoat alone without a coat, unlike some re-enactor’s interpretations.

If they did not wear the jacket, they wore a “Shortgown” the same as the English and French. This was a somewhat fitted though comfortably loose around the body jacket like garment. The main difference between the jacket and shortgown being the sleeves were cut with the body of the Shortgown and did not have an inset sleeve. These were the garments of the working, poor, and rural class women.

NOTE: the current wearing of the “French or English Bodice” is NOT correct. This is when the sole upper garment is a vest-like structure over the shift without stays. It was actually the opposite – it was fine for a woman to appear in public wearing only her stays over her shift, but never to appear without he stays.

Stays

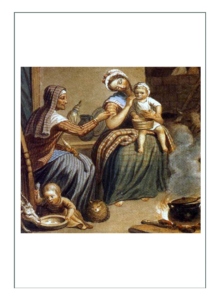

Women had to wear stays. Always. At home they had lighter and less structured ‘jumps’ as an option. These were improper to wear in public, except right after childbirth.

The difference in stays was in the cut and quality of materials. Working women liked the more flexible stays of natural and woven materials because they could move easily in them. Most Scottish women wore stays of linen or leather. The leather was scored where there would be bones in linen stays, so the woman could move.

Boning was of straw or caning like a broom thatch.

Stays were so important to the Scottish society, that there were charitable organizations formed in cities and villages to provide them to women or children who could not afford them. The term “loose woman” refers to a prostitute because she did not wear stays.

All people and especially children wore them because of malnutrition and the prevalence of rickets. They felt wearing stays gave support to backs and bones that were at risk. They also wore them simply as a back support for working.

Stays in the Highlands, if well made, were NOT intimate garments. There are portraits of women wearing only their stays to church, and women often went to market wearing only their stays and shift with a petticoat.Women in Scotland for the most part were bareheaded except in the 17th century. In the 18th century they wore a version of cap the same as their European sisters. Sometimes they wore a “fillet” cloth wrapped around their necks and over the head. “Fillet” was the French word taken by the English and was basically a more flexible version of the 18th century “fichu”.

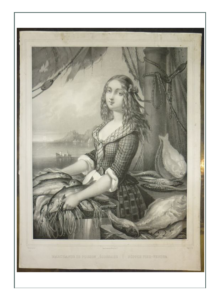

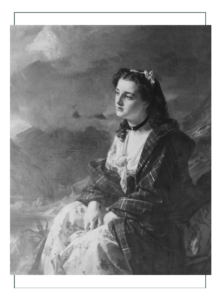

NOTE: in the Flora MacDonald photo from which re-enactors take their inspiration, her costume is only fictionalized as the “real rural” ensemble. It is not. A closer depiction would wear jumps or stays with a petticoat and shift than that portrait.

Much was handknitted. Men learned to knit as boys as well as girls. Men wore a bonnet with a “plant-badge” which was something of significance to their Clan: e.g. sprig of holly for MaClean, or seaweed for MacNeil; yew for Frasers cut from an ancient tree on their ancestral lands at Stratherrick, etc.

Their brogans (shoes) were made of rawhid. The Chief had 3 eagle feathers in his bonnet. Many chiefs, highly educated in other countries, spoke multiple languages and were masters of diplomacy, even if the English and French made fun of their clothing.

Favorites of women:

checks – little or big

yellow – a favorite for everything, as it was easy, cheap, pretty, and had a personal tie to ancient Scottish history

Plaids, Tartans, Arsaid, & Kirch

Or is it the English & Colonial Fashion? Examples of REAL Scots in Portraiture & Extant 1740’s-1770’s

Re-enactors and costumes

Textiles & Weaving Traditions

(taken verbatim from article by Edward Harrison, 1935)

Weaving is one of the great arts – world wide, set at the very gates of civilization – uniting in a way all civilisations, all barbarisms, all people save those in the tropics, in that desperate struggle for life against the implacable destroyer and creator. Nature.

Weaving has developed from the purely primitive function of protection to a vehicle of thought and imagination. Weaving did more than steam, more than aircraft, to tell us of the world and other people. It brought the civilisation of the Mediterranean to Europe, that brought the various ingredients together that made the Anglo-Saxon race, that joined the great continents of America to the outside world – Phoenicians, Venetians, Vikings, Conquistadores, Puritan fathers, French emigrés, Highlanders cleared from their native glens to make room for sheep – and as though the subject were too confined, the American expedition at present exploring the ancient sites of the Bible has just unearthed coarse linens evidently woven two or three thousand years before the Birth of Christ.

The Trade of Scottish Woolens has kept its old craft tradition in Scotland . The old, skilled craft evolved slowly in our old, poor country, much isolated by its poverty and as things then were by its remoteness from the centers of light in Southern Europe.

In the construction of ordinary cloths there are two sets of threads : the Warp, running the long way of the web of cloth and for ordinary purposes of clothing from your head to your feet; and the cross threads, the Weft, or more anciently the Woof, a word only remembered nowadays by poets.

In the simplest form of cloth construction the first weft thread is passed under the first warp thread and over the second and so on right across; the second weft thread – which is really the same thread on its return journey – passes over the first warp thread and under the second, and this simple weave is called the Plain Weave.

But the great bulk of Scottish Woollens are made in a denser and more pliable weave which we call the Common Twill, but which has many other names elsewhere. It is over two and under two, moving one thread onwards each time. Apart from certain figuring threads used in decoration of cloths and certain threads forming pile effects like carpets, tapestries, and velvets, all woven cloths are constructed on these lines.

As the yarn is brought in from the spinning room it is fast wound on to various types of bobbins or, as we call them, pirns. Other machines are winding down hanks of coloured yams that have been dyed in the yam. For the warps the yam is usually wound on “cheeses” – solid cylinders of yarn with a wooden core possibly six inches long and four or five inches in diameter – holding somewhere about three-quarters of a pound.

Several ingenious types of machines are winding the weft on to long narrow bobbins for the shuttles. The slick work of the girls who tend these machines is delightful to watch – as is all dexterity. True, the eye is easy to deceive, but no eye can follow the movement of the worker’s fingers as she ties one thread to another.

Next comes the warping, rows upon rows of the cheeses are being built into the bank of the warping mill. A “bank” is a tall holder something like a bookcase, and in it, each on its steel spindle, the cheeses are arranged according to the pattern to be produced, just as the volumes in a bookcase follow some prearranged order. From there these threads are drawn off on to the great sparred cylinder of the mill, where by various devices each thread is kept in its proper place – and as the cheeses whirl round, the bank-boys watch the whole rushing spider’s web to signal to the warper to stop his mill if a thread breaks or runs out. An elaborate and tricky job on complicated work such as our Scottish manufacturers make.

The bell rings to show the needed length has been warped, and then the contents of the mill cylinder are unwound on to the weaver’s beam, a heavy, strong, wood-clad steel affair, say, nine feet long and eight or nine inches in diameter. Every individual thread of the warp on the beam has to be drawn separately through a little eyelet in the weaving harness, again all according to a more or less elaborate scheme, rhythmic and balanced in its sequences like a verse of poetry.

And all this time other preparations are going on. Some yarns are going through the doubling machines where two or three or more threads are being twisted together, sometimes at two or even three stages so as to produce some particular effect of colour blending – sometimes only to produce thicker or stronger threads. The twister spindles run invisibly at possibly two or three thousand revolutions per minute, putting on the turns per inch with mathematical precision according to whatever may have been decided. “Chains” are being put together by which the automatic action of the power loom changes the shuttle colours according to the pattern of the cloth, however intricate the design may be. Other chains are being made up by which the weaving mechanism is controlled and by means of which the actual construction of the cloth is decided, apart altogether from the colour scheme it may be carrying.

And so we arrive at the point where all these diverse activities converge in the power loom. The weaver’s beam is lifted in and connected to the machinery. The weaving harness with its innumerable threads, each in its little eyelet, is tied up. The warp threads are attached to the cloth beam in front of the loom. The chains for the weaving and shuttle mechanisms are placed in position. The wheels governing the number of weft threads per inch are put on. The “reed” for beating up the weft threads put across the web by the shuttles is fixed in the “lay”.

The different colours for the shuttles are brought from the winding frames and put into their allotted shuttles. The shuttles are placed in their proper “boxes”. The power-loom tuner in charge of the gang of looms weaves through a repeat or two of the pattern, examines the work carefully along with the standard for that pattern and sees that no thread has been wrongly placed. The man in charge of the work of the power-loom shed checks everything over again and sends for the weaver who looks after that loom. The weaver pulls over the starting handle and her machine adds its part to the infernal pandemonium.

Weaving looms around the world are built on the same principle but they are slightly different in each country. It’s actually natural that the craft of weaving in Scotland differ from the one in Ukraine or in India. So, there are special tricks and secrets of using a traditional loom in each country. Here is a short tutorial on how to weave on a traditional Scottish weaving loom.

(Taken from Scottish Textile Guild and Balmoral Hotel websites, ver batim)

The Birth of Highland Dress

The traditional garment of the Highland clansmen is the kilt (belted plaid), which is suitable for climbing the rough hills. Each clan had its own colorful pattern for weaving cloth and these patterns are called a tartan.

Just as medieval noblemen were recognized by their family crests, Scottish clans created signature tartans. Each tribe conceived a pattern unique to them, which was worn around the waist like a kilt and draped over the shoulder. The fabric became so significant that it was banned for a number of decades as the government attempted to bring the clans under their control. However, the opposite happened and following the repeal of the Dress Act in 1782, tartan went from being a Highland tradition to the symbolic national dress of Scotland. Tartan is still used to this day, especially at important events such as national sporting events, weddings and cultural celebrations such as ceilidhs (Gaelic dances).

Nowadays the kilt is no longer a historic dress but a national costume, proudly worn for special occasions such as weddings etc. There are currently over 4,500 different tartans and you can even have your own tartan invented if you like. The most renowned mill today is probably the Edinburgh Woollen Mill at the beginning of the Royal Mile.

A Vital & Viable Industry

The Borders region – a land of rolling hills, fabulous forests, and fast-flowing rivers – is rightly famed for the creation of first-class fabrics, woollens and tweeds that are favorites with everyone from local farmers to the world’s top fashion designers.

Although the history of weaving in the Borders dates back to the Middle Ages, it was not until the 1700s before linen production became a local cottage industry. This began in 1777, when the Manufacturers’ Corporation of Galashiels was formed. Although it had just 23 members, they were filled with ambition and had built their first mill by 1800.

The Borders hills had long been famed for their sheep, and the fast-flowing Gala water gave the mills the power they needed to drive the industry forward.

From Fiction to Fact

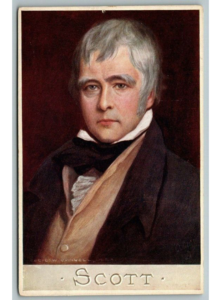

Galashiels soon became known throughout the world as a producer of checked cloth called ‘Shepherd’s Checks’ or ‘Shepherds Plaid’. However, this was soon christened ‘Tweed’, possibly after the local river that marks the Border between Scotland and England. This particular cloth was favored by Edinburgh-born author Sir Walter Scott.

As Scott’s books – many of which were set in the Borders – found fame, first across Britain, then Europe and the rest of the world, the fabric known as Tweed began to become more and more fashionable. Avid readers of his famed works, which included Waverley, Rob Roy and the Heart of Midlothian, would study portraits and miniatures of Scott to see what he was wearing, then follow his style tips.

This wasn’t the only time Scott sparked a fashion craze. In 1822, he was asked to oversee the state visit of King George IV to Scotland. This was a momentous occasion, with it being the first visit of a reigning monarch to Scotland in nearly 200 years, and Scott was keen to create a spectacular event.

His insistent inclusion of tartan pageantry throughout the visit went on to spark a revival of the fabric. This event also helped establish the tartan kilt as being so synonymous with Scottish identity. The Highland fabric also went on to become all the rage outside of Scotland, with people clamoring for it across the UK and Europe.

Royal endorsement

In 1934, when textile company, Pringle of Scotland, appointed Austrian-born Otto Weisz as the first full-time designer in the knitwear industry, he set new global trends. Not only did he invent the knitted twinset, a favourite look with female film stars of the day, he also reimagined the ancient Argyle pattern to create Pringle’s trademark diamond design, which became globally popular after being adopted by the Duke of Windsor.

Borders tweed and woollens are still at the heart of today’s weaving industry and are still favorites with top designers and fashion houses from London’s Saville Row, to Paris and Milan. Add in the area’s long-standing expertise in weaving fine cashmere, and you soon understand why the industry is still a major employer in the Borders, providing jobs for around 3,000 people, as well as contributing hugely to the local economy.

Fashioning the future

Building on over 200 years of tradition, Borders textile manufacturers are still at the center of an international network, importing the finest raw materials from across the globe, and exporting finished fabrics and clothes to the fashion capitals of the world. From fashion catwalks to golf fairways, Rodeo Drive to football terraces, Borders-designed and manufactured fabrics and knitwear grace some of the most fashionable shoulders.

Long recognised as Scotland’s premier textile manufacturing region, the Borders is also home to Heriot Watt University’s world class School of Textile and Design, in Galashiels. The school attracts students from around the world, as well as visiting lecturers from some of the top fashion houses.

And it’s not only in traditional materials where its expertise lies, the college is also a leader in the emerging fields of smart, protective and waterproof fabrics.

Galashiels graduates have also gone on to work at some of the world’s top fashion houses. Tartan is Scotland’s most famous fabric. Originally the cloth of Scottish warrior clans, tartan patterns tell tales of heritage and ancestry. The checked fabric is a recognised symbol of Scotland and has a long and storied history that stretches back many centuries. As The Balmoral unveils its new tartan uniform, designed in partnership with Kinloch Anderson, we take a look at the art of Scottish tartan making and discover the meaning behind hotel’s bespoke fabric.

Changing patterns

The industry has also seen major changes over the past few years. When Borders cashmere specialist Barrie Knitwear’s parent company collapsed, French fashion house Chanel, swooped in to buy the brand. Today, ‘Boutique Barrie’ has outlets in London and Paris, while the mill’s cashmeres are sold in Chanel shops around the world.

The region even boasts its own dedicated textile museum, at the Borders Textile Towerhouse, Hawick, and a Textile Trail – which links 10 different textile companies, celebrating the local tweed and knitwear industry.

Leading producers today include Barrie (Chanel), Pringle of Scotland, Lyle & Scott, Hawick Cashmere, Hawick Knitwear, Holland & Sherry, House of Cheviot, Johnstons, Caerlee Mill, Lochcarron, Lovat Mills, Scott & Charters, Shorts of Hawick, Hawico, and William Lockie.

Although many of these former family-run firms are now owned by multi-national brands, or have exclusive supply deals with top fashion houses, they still adhere to the same high standards of design, manufacturing and production that made their names a byword for quality.

The great news is that these centuries-old traditions will continue long into the future with the recent announcement of a new centre of excellence, which will open in Hawick in 2019. true to the industry’s roots, the centre will open in a transformed mill building in the town and will look to address “critical skills issues” in the sector and provide a range of training programmes.

Scotland’s fashion industry Today

Scotland’s textile industry boasts an enviable client list which includes Chanel, Hermés, Gucci, Louis Vuitton, Prada, Ralph Lauren, Donna Karen and YSL, as well as Boeing, BMW, Alfa Romeo, Jaguar, Emirates Airlines and British Airways.

Harris Tweed, the only fabric in the world governed by its own Act of Parliament, celebrated its centenary year in 2011. The cloth is woven only in the Outer Hebrides by crofters in their own homes, using methods that are centuries old. It’s widely sold in the UK and exported to more than 50 countries around the world. Recently, sales of Harris Tweed have soared and the total production has reached more than a million metres of cloth a year.

With craftsmanship perfected over 300 years, Scottish cashmere is another guarantee of quality. Only one mill in Britain carries out the entire cashmere weaving process from raw fibre to finished garment and that mill is located in the Scottish Highlands. Produced since the 18th century, cashmere is, for many, the last word in luxury. Scottish cashmere is supplied to some of the world’s most prestigious fashion houses including Chanel, Prada, Louis Vuitton and Burberry.

Scotland is also home to some of the world leaders in medical and performance textiles with the presence of Ahlstrom, WL Gore, and DuPont., all based in Scotland.

Scottish Fashion Today

The national costume of the Scots has changed little even today from its origins. The “breacan-feile”, a plaid made from 16 yards of tartan which has been plaited and fastened with a belt around the body is the standard. 1/2 of that width hangs from waist to knee, and the other half is tucked up and over the arm and pinned like a cloak.

“Thews”, close-fitting breeches with stockings attached are sometimes worn (in history by upper classes). These too are made of Tartan whose patterns and colors distinguish the Clans.

Today the belted plaid is worn with stockings that are gartered just below the knee. A long waistcoat is worn. It is usually made of cotton velvet or woolen cloth. The dirk and sword are worn, the dirk in the top of the stocking, and the sword at the waist.

Coarse leather shoes called “brogans” or sandals of rawhide “cuaran” are worn. A tam-o-shanter or a cocked bonnet is on the head. A “sporan”, a purse made of skin with silver mountings hangs below the belt in front.

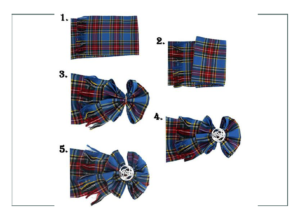

The Highland Lassie wears a “warm cloth bodice” over a “skirt”. She adds 3 yards of fine worsted wool plaid (less than a man or it will engulf her in bulk). It is pulled over the head and pinned to the bottom of the skirt on the right hand side. The short end goes around the left arm and folds at the left shoulder so it can be held there by a brooch pin over folded pleats.

Click here to return to the Susan Hurlbutt project page