Understanding the Titanic Era

Titanics Were Happy Elites from “La Belle Epoque”

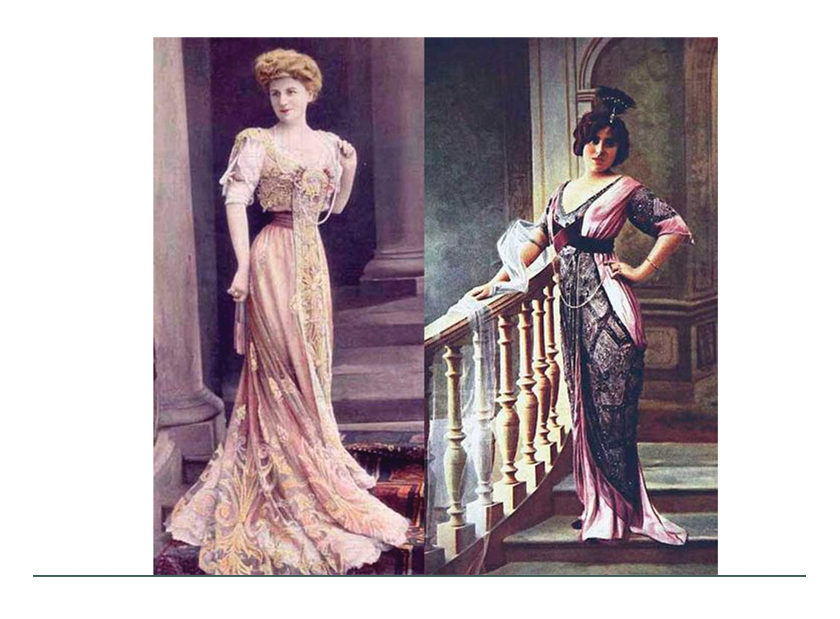

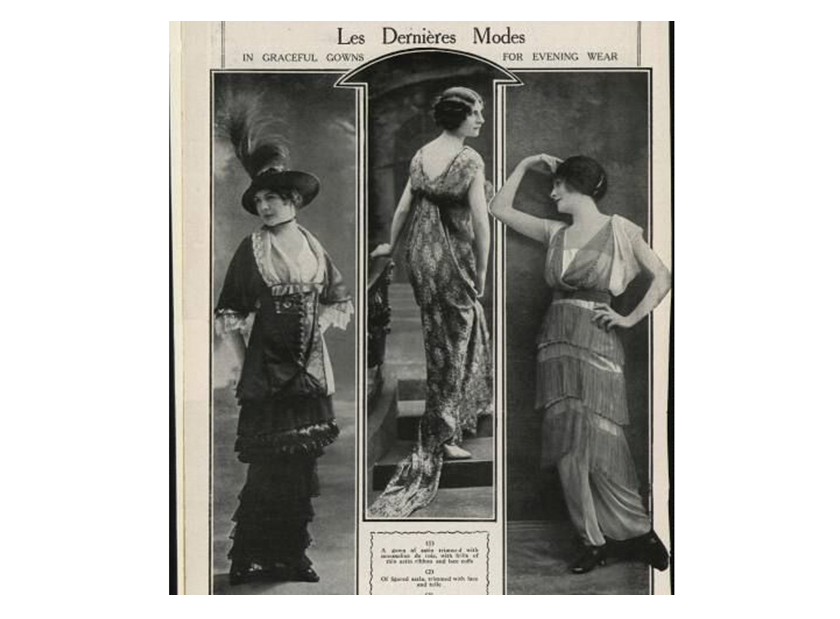

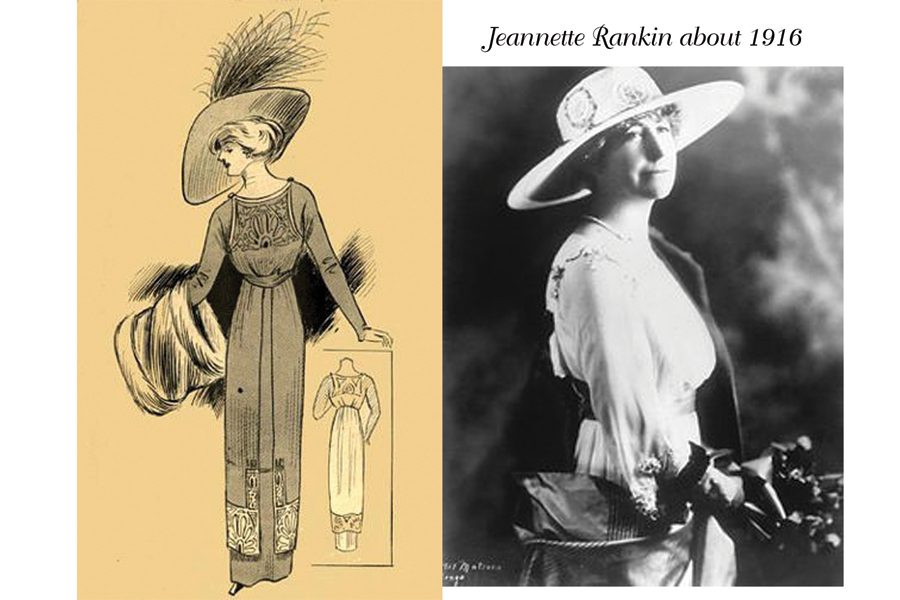

“Titanic Fashion”, worn by some royals of influence like the Grand Duchess of Russia, was not created by kings like Edward, but was a “pocket” out of Edwardian fashion coming from “La Belle Epoque” high fashion houses of Paris which defined grace and femininity. It was an attempt by designers like Doucet, Collet Souers, Paquin, and Lucille to create the MOOD of luxurious living and as an expression of women’s new and daring place as thinking individuals.

While Edwardian fashion was mass produced, “Titanics” were custom ensembles with amazing detail and superb construction. It did NOT include sports or work wear, except maybe that required for arranging flowers or wearing to visit a farm to pet the lambs.

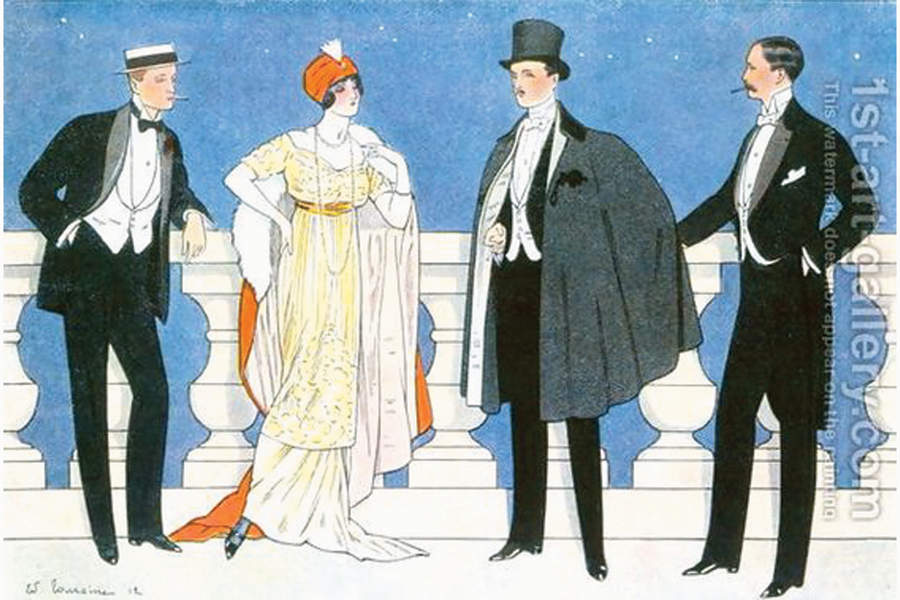

It was a good time to be a tailor as most elites wore a lot of different clothes and typically took 18 trunks to travel. They wanted to be SEEN, and they paraded down streets, at the Regatta, or at the races in full finery.

Notable Titanic Designers

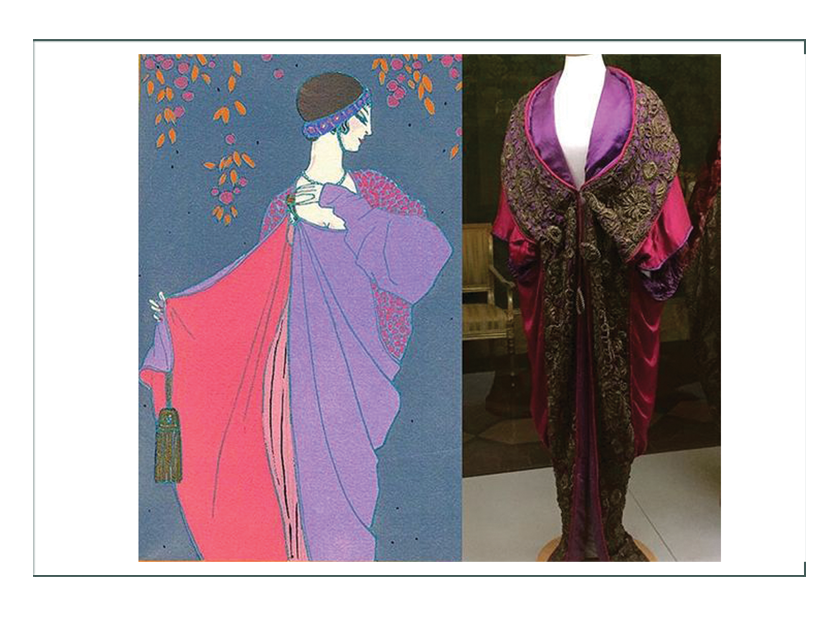

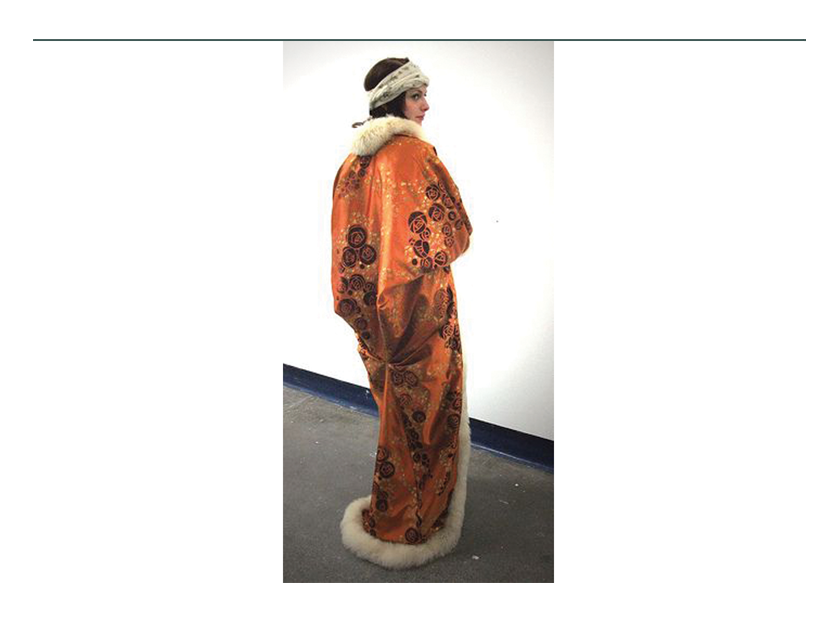

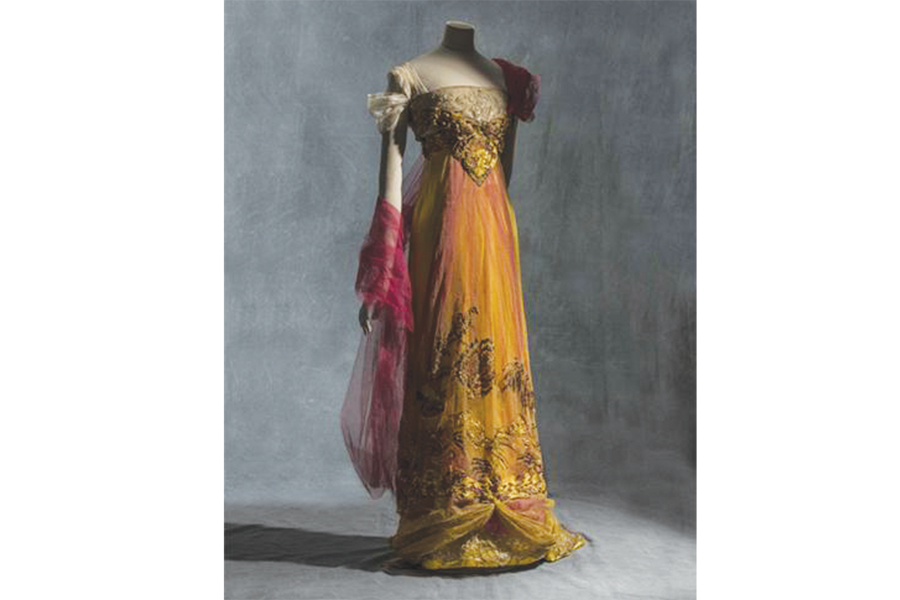

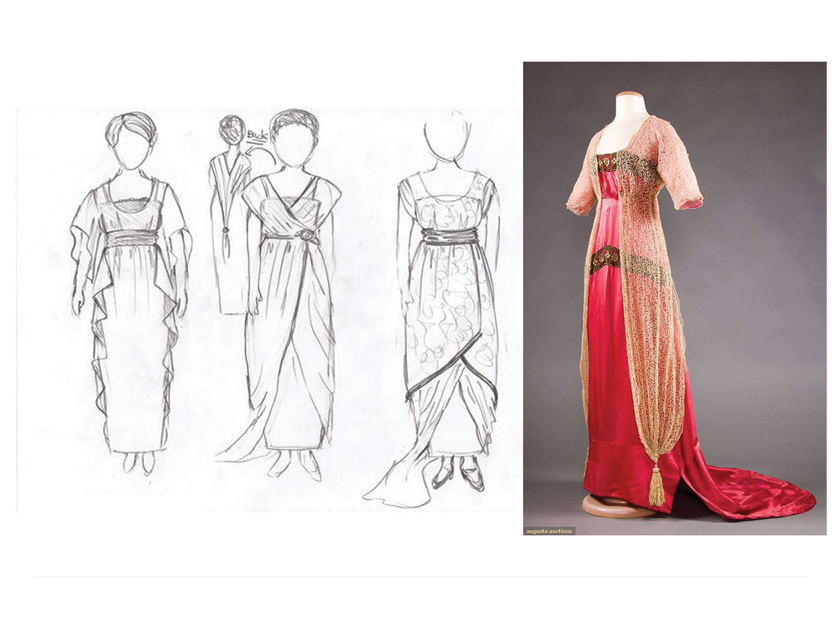

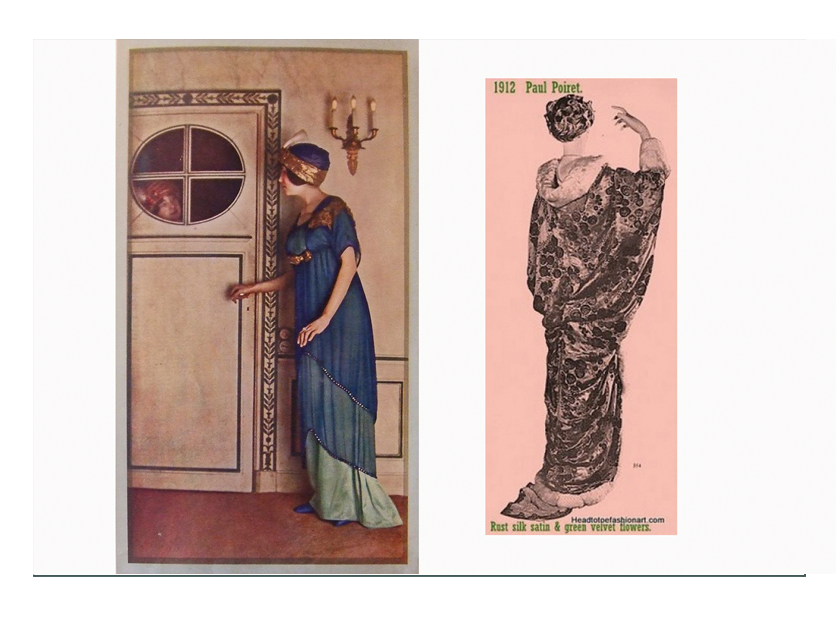

Jean-Phillipe Worth and Poiret Paris Fashion designers are particularly noted as “Titanic”. Both drew influences from the orient and middle east in the use rich silk fabrics with intricate embroidery or trimming. The era started with frills and ruffles, but ended up with gorgeous draping silks with highly saturated color and patterns.

Designer Worth used mass produced components and built them into ensembles with beads, jewelry, fringe, lace, braids and tassels. Performing artists liked his elaborate designs so much they wore their stage costumes out in public.

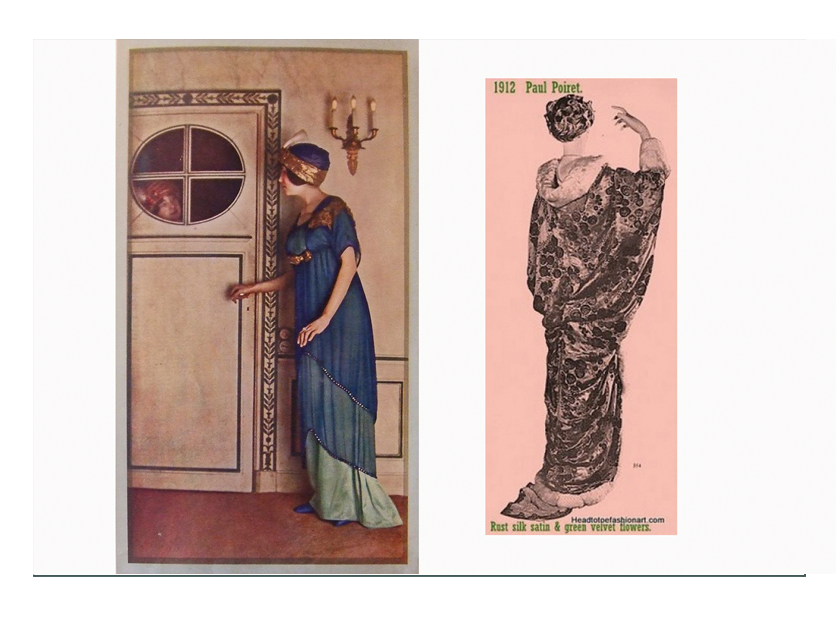

Poiret, seeing the new print process that featured large blocks of solid color, designed his dresses the same way so they would look good in his ads in magazines. Poiret introduced the first modern, straight lined “dress. He made slim straight skirts with few undergarments.

Like the 1800’s “Directoire” style, “Poiret’s Empire” had freedom of the body and movement, and allowed a higher waist. The silhouette was rounded and sensuous with curves of bust and derriere, although these were not emphasized.

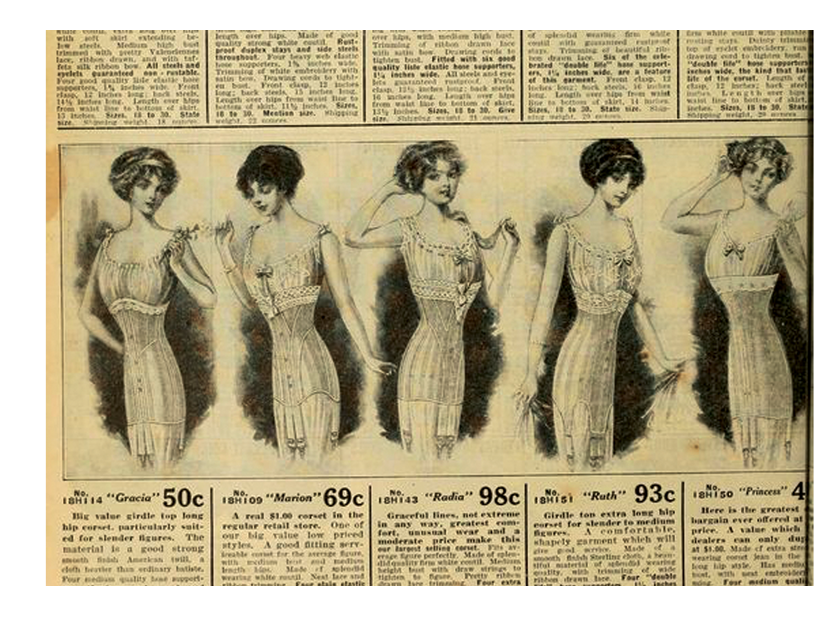

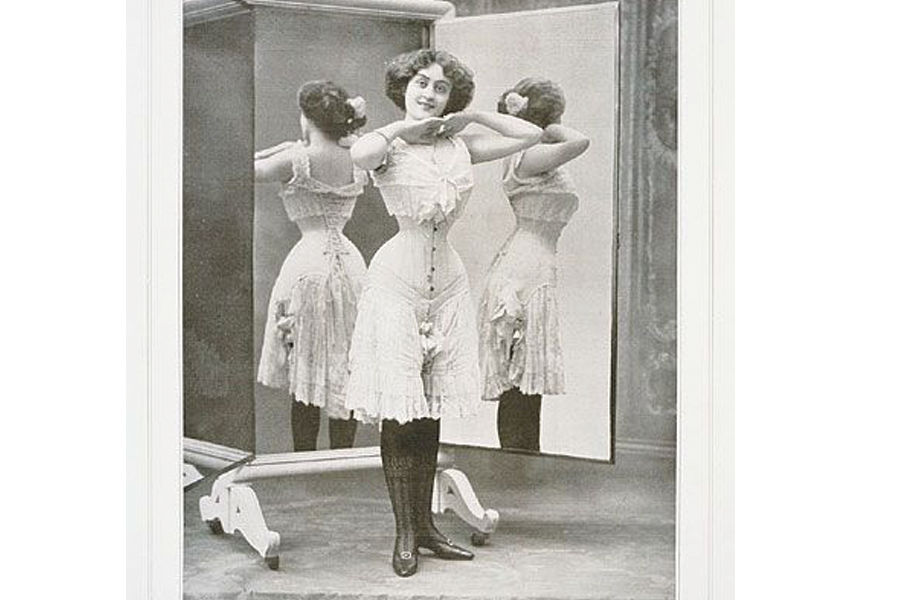

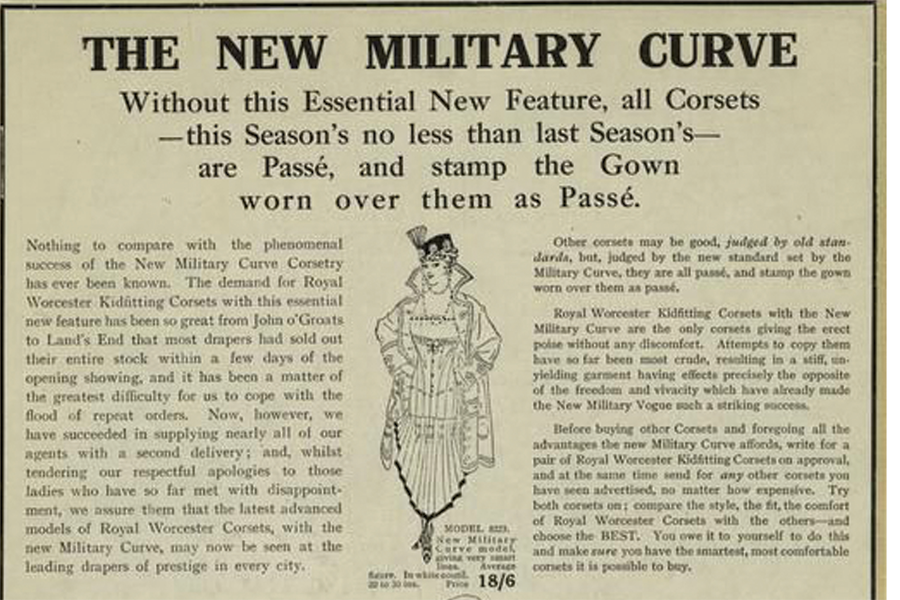

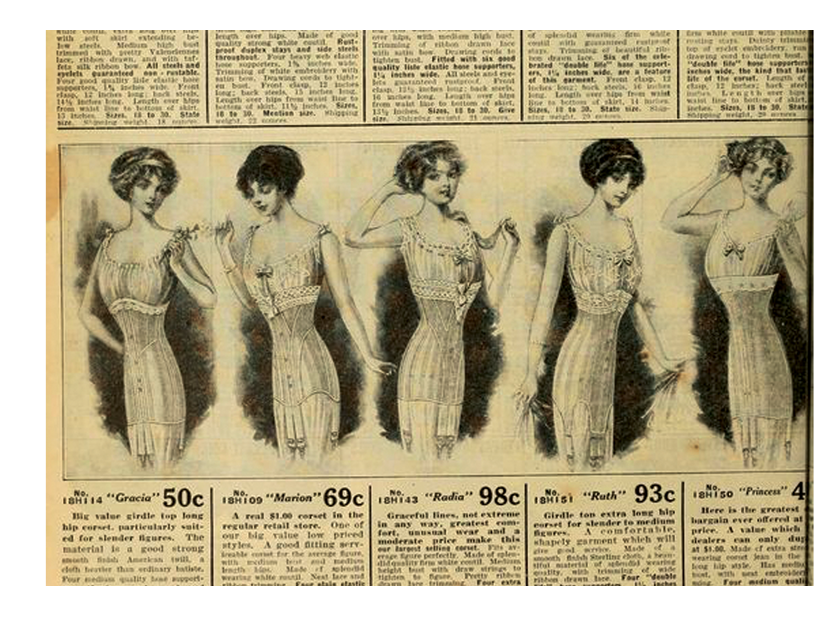

Women had to get rid of the “S” corsets and wear one that almost reach the knees. Poiret encouraged women to get rid of it all together to adopt the brassiere or “corsetless chemise”. The new corset had NO control of the body, and its purpose was to make a smooth body from bust to foot.

Poiret was sensitive to the mood of society and the trends of painters and artists like the Impressionists. He was strongly influenced by Ballet Russe costumes which used lovely rich fabrics and excessive ornamentation to give the dancers the look of sensuous harem girls.

He brought color and brilliant hues at a time “sweet peas “were being worn by other Edwardians. His exotic designs were based on harem pants. The longer slimmer line of the bodice and skirt created a visual whole that appeared long and slim, but it was really about the fullness and sensuality of the wearer. For this reason, the same as in 1800, it was mostly young women who looked good in Titanic clothing.

Poiret introduced “orientalism” in fabrics, patterns, and colors that were Asian with synthetic dyes and prints. He also introduced to Europeans and American Sumerian, Persian, and Turkish costumes. These were simple shapes of kimono jackets, long tunics or trousers, and saris.

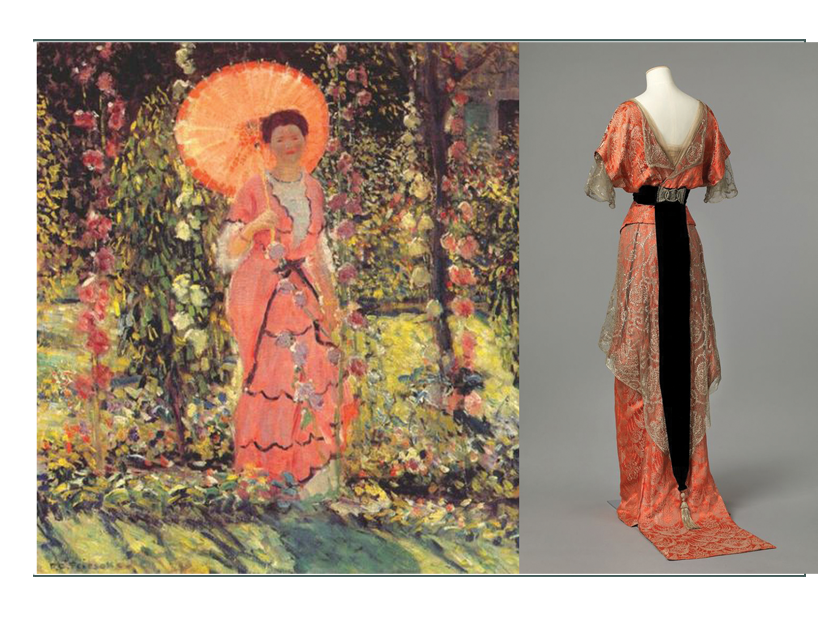

Impressionist painters loved Poiret. He took inspiration from them, and they took inspiration from him.

The rich saturated colors of artists like Monet were replicated in Poiret’s Titanic designs.

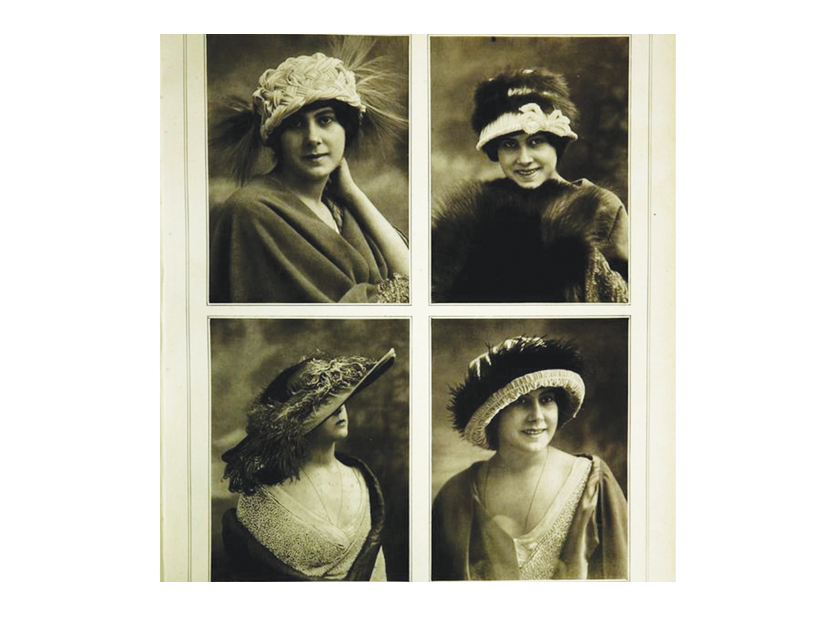

It is orientalism that distinguishes “Titanic” fashion from other Belle Epoque and Edwardian fashions. Fur was a symbol of orientalism and was used by all the designers on sleepwear, hats, coats, and edges of gowns. The last notable design of Poiret, the “Hobble Skirt” bound women at the ankles.

Design Houses Paquin and Lanvin made the same concepts but in ensembles that women could actually move around, and so Poiret dropped in popularity although artists of “Art Nouveau” showed Poiret’s designs in their work because the quality of materials and “natural forms” were like what they were doing.

The “V” neck was introduced by the new class of designers, and it so shocked the world it was denounced by the Church.

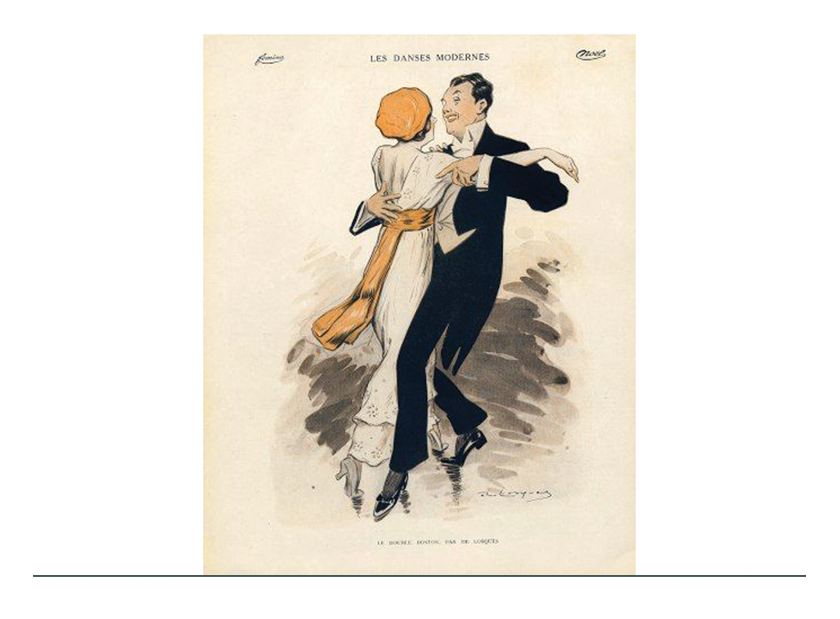

The new Ragtime dances had women imitating animals. The Grizzly Bear, Turkey Trot, and Bunny Hop meant the new narrow dresses need to have slits so they could move.

Callot Soeurs french design house introduced draping on live models. While Worth had invented the runway fashion show, Soeurs added setting, music, and lights for specific customers. Soeurs also brought Russian influence into a design line they called “Petrograd” which used rich fabrics and metallic threads.

Soeurs’ tea gowns were of silk and organdy – multilayers in pastels and trimmed with costly laces which were their trademark. Asia and Africa inspired a line called “robes pheniciennes”.

One of Soeurs’ innovations was to combine different design elements into one garment; e.g. kimono sleeves with Algerian burnouse.

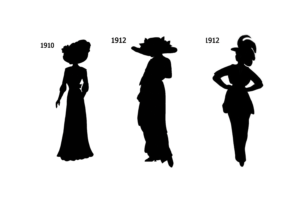

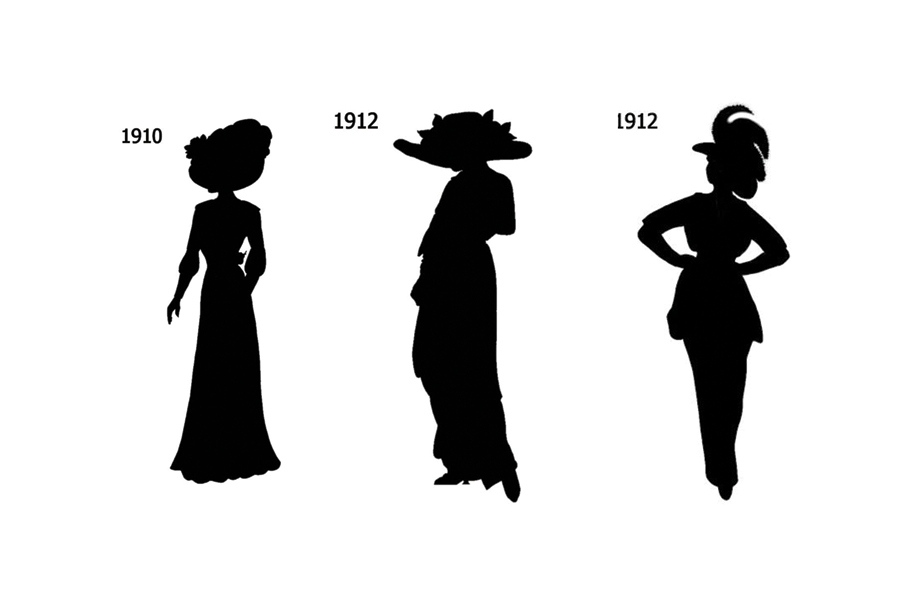

THE NEW SILHOUETTE

It is difficult to generalize “Titanic” since it’s a “feeling” and not a “style”. It evolve and changed within “La Belle Epoque” as it changed hands and designers. What started as the hourglass figure with ciurasse basque became the figure 8. Next was a slim line with the “S Monobosum”.

The silhouette became symmetrical again, and shortened in length overall as the waistline rose. The waist then suddenly DROPPED drastically to the hips, and the Asian and Middle Easter influences and draped design came.

Although designer Poiret loved it, wearing purple was avoided by most women because it looked like brown under the new gas lamps.

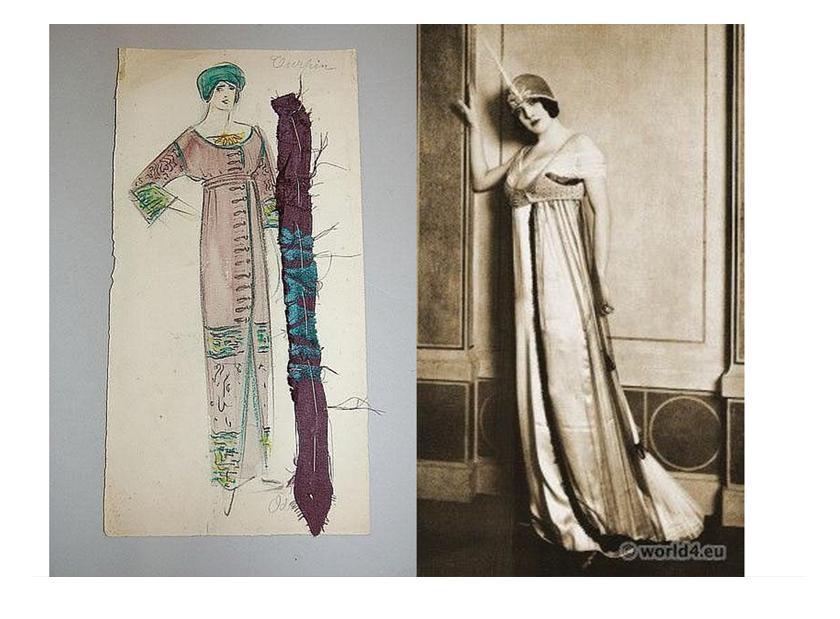

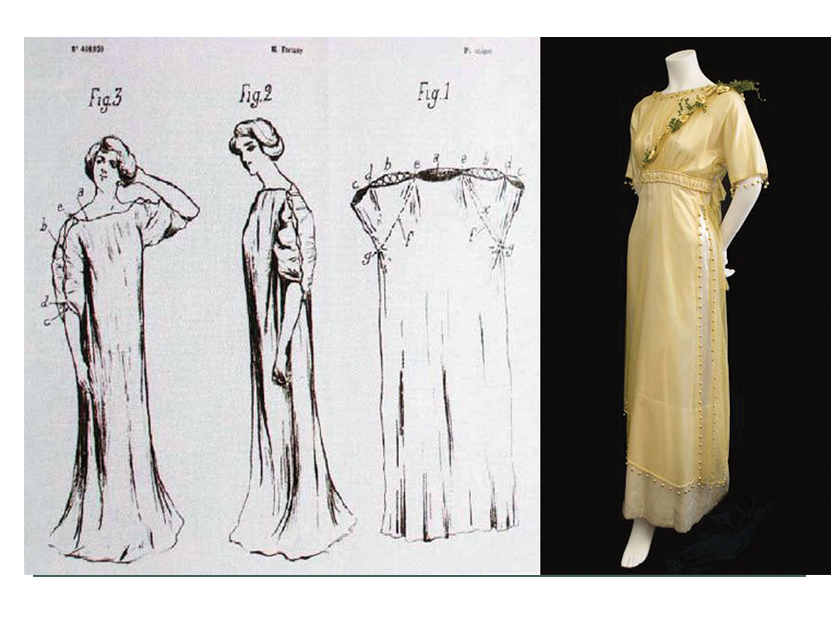

One of the most interesting thing about gowns of this time – gowns designed by famous designers Lanvin, Poiret, Vionnet, and Lucille – is that they were all variations on the same theme The invariably consisted of a satin underdress with a boned bodice, most often sleeveless or with simple shoulder straps, with an attached slim skirt – both fastening at center back with hooks and eyes.

Over this was draped an overdress or tunic, and this is where GREAT variation in style appeared. The overdress was typically a see through fabric such as silk net or chiffon. Sometimes it was cut to fit closely over the satin undergown, but more often than not, it was draped over the undergown and the unique properties of the sheer fabric were allowed to display.

This style was worn from 1906 until the “Great War”. Supposedly designer Poiret started the style because he could not sew so he designed by draping fabric on a mannequin, but many of the designers were draping at the time and not drafting patterns ahead of him.

Many of the Lanvin and Poiret gowns were nothing more than square-cut bodic tunics held at the waist by a sash worn over a basic underdress. These were just long pieces of fabric with a hole cut out for the head and wrapped at the waist.

Another characteristic of this gown style is the decoration of the sheer fabric. gemstones, glass beads, and metal or silk embroidery were added to the chiffon or net until it was literally dripping with ornamentation. Hems were weighted with lead shot so they wouldn’t flop about. Many of the gowns of this time have not survived because the heavy decoration tore the delicate material and it all disintegrated.

All designs at this time except the very highest fashion lingerie and gowns were made by machine. The intricate and elaborate trim was machine made in many cases. Fitting was draped from the fine fabric rather than tailored with patterns as were necessary with the tight bodices of the late 1800’s.

Sashes were used to create the illusion of a high waistline, although the dress was based on the natural waistline.

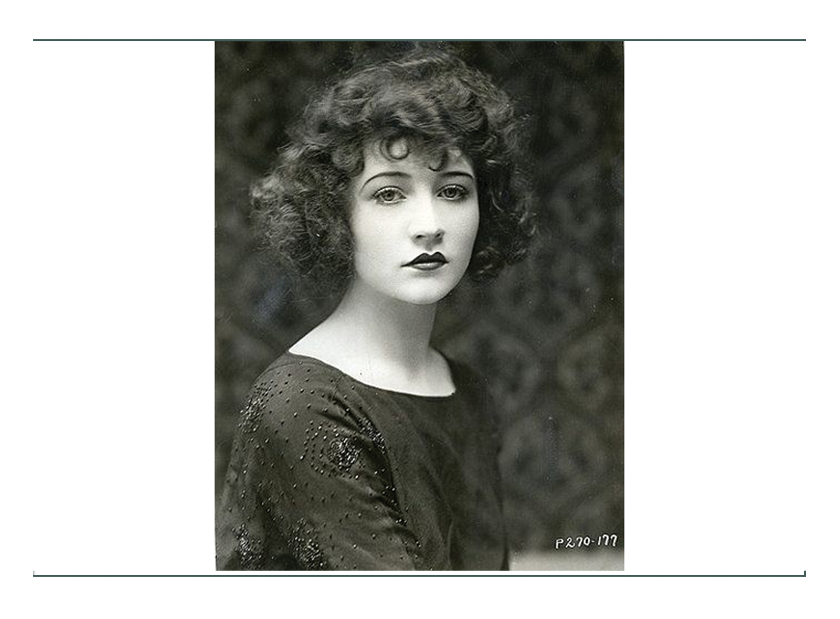

The pouty mouth was all the rage, so women practiced the letter “P” to be fashionable.

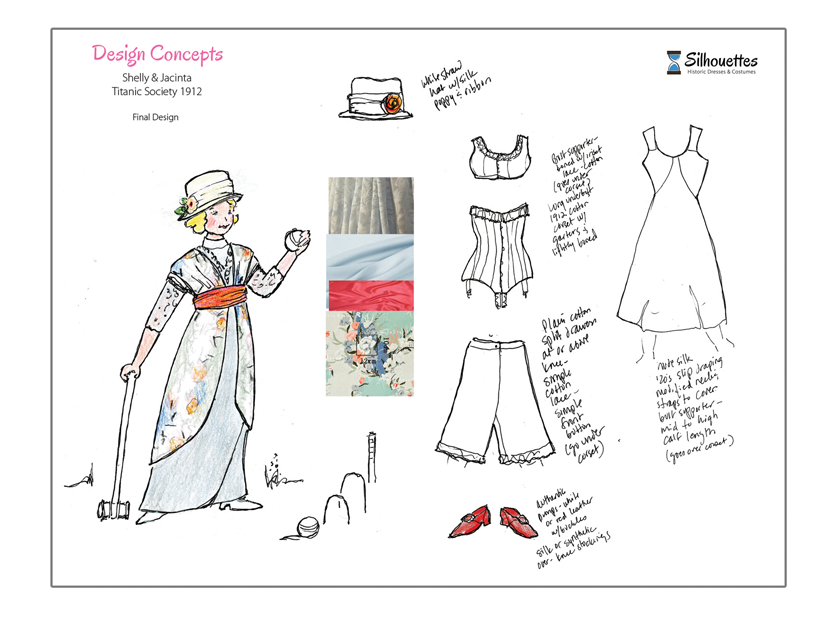

Our “Titanic” model is very good at p’s and wears an authentic art nouveau sterling silver manmade diamond “tennis bracelet” with gold reproduction necklace and earrings with a square cut blue “diamond”.

Her hat is of silk on a straw base, with a flower to match those in the dress fabric. Hats were many and varied at the time, but always big with silk flowers like the Edwardians. There were hats for every activity and season.

Hair was carefully coiled and braided; the bun lower than previous eras to support the hats which were worn flatter on the head than before.

This gown was entirely “draped” just as we felt like doing it.

The China silk tunic features the highly saturated and bold print with outlines of the Asian influence. The bodice and skirt are of a coordinating more muted single color pure silk to show off the tunic’s designer fabric.

Note the difference in the “floppiness” and drape of this more modern silk than the stiff, rustling taffetas and dupioni silks earlier in history

The silhouette is typical of a Poiret design with influence from Turkish and Persian “pants” – very daring and only done by the few high class and young, slim women who dared.

The bodice is boned because underneath is only a “bust bodice”; predecessor to the brassiere. Since the breasts now hung over the corset, and fabrics were more clingy and soft, extra structure in the form of corset boning was added to the dress itself for modesty and shape. Our model’s bodice is lightly boned with plastic.

Bodice and skirt are one piece of the same fabric, but there is an over layer of cotton lace in a same color for texture and interest. This is a “casual” or afternoon on the lawn type dress. More formal or high end garments would have instead of lace extensive beading, embroidery, or 3-dimensional lace which is most readily associated with Titanic ensembles.

We chose to keep this very simple, clean, and classy in the spirit of Poiret or Lanvin, so that it shows off the body and beautiful construction and subtle structure.

It has the “Directoire” waistband and long line seen in 1800. It might still have had a train, but this is an afternoon leisure ensemble.

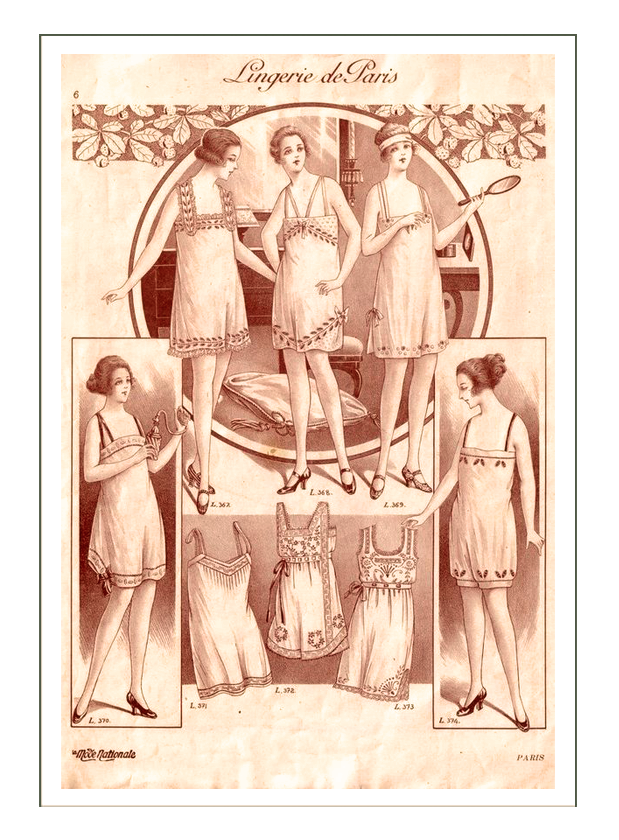

By the 1920’s the “petticoat”, “drawers”, and “chemise” would be replaced by the “slip”, “tap pant”, and “bra”. At this point women wore a transitional version of each.

Our model has on a clingy pure silk “slip” with narrow straps of self fabric in the design that would be prevalent in the next decade, but which was daring and newly introduced by designers in 1912. This acted like the old corset cover and petticoat, to protect the delicate outer fabrics.

As the 1920’s approached, the leg replaced the waist as a fashion focus, and the bosom receded in importance. For slim, youthful figures, all that was required under a chemise frock was a simple straight camisole. This one is of ivory handkerchief silk, with mother of pearl buttons, adjustable silk ties, and vintage lace. It can be worn with the buttons to the front or the back, making it easy for a woman to dress herself.

This time witnessed the beginning of the revolution in women’s fashion unequalled since the French Empire. French couturier Poiret freed the feminine form from the artificial constraint of maintaining an unnaturally tiny waist or exaggerated curves. Waists loosened, disappeared under tunics, or rose to the Empire line. There now was no function for the heavily engineered corsetry that had imprisoned women for a century.

Hollywood stars from this period convince us that daring women may have dispensed with lingerie altogether, but the average American woman reacted favorably to the comfort and luxury of silk or rayon pants, teddies, and slips.

Corsets were still in style, but they had changed shape entirely. In 1910, English women donated their corsets to yield 28,000 pounds of steel to the war effort. This meant they needed something different to wear underneath.

It might be said discarding the boned corset in favor of softer lingerie did more for women’s emancipation than the vote.

Click here to go to the Design Development Page (next)

Click here to go to the Main Page with the Finished Project