The Waistcoat & Men’s Historical Fashion in Brief

“In men’s wear, a continuation of the doublet of the Middle Ages. A sleeveless but lined body jacket, waist-length, and worn between jacket and dress shirt. Made single- or double- breasted, of constructing color or fabric or matching the suit cloth. A backless waistcoat appeared in the 1950s for summer wear. It consists of two front pieces buttoned center front. Two narrow belt pieces, attached to the sides, buckled in back; the fronts also joined by a narrow neckband in back.” 1

“The waistcoat, or vest (as it is known in the United States), is a close-fitting sleeveless garment originally designed for men that buttons (or occasionally zips) down the front to the waist. Produced in either single or double-breasted styles, the waistcoat is designed to be worn underneath a suit or jacket, although it does not necessarily have to match. Similar garments are worn by women.” 2

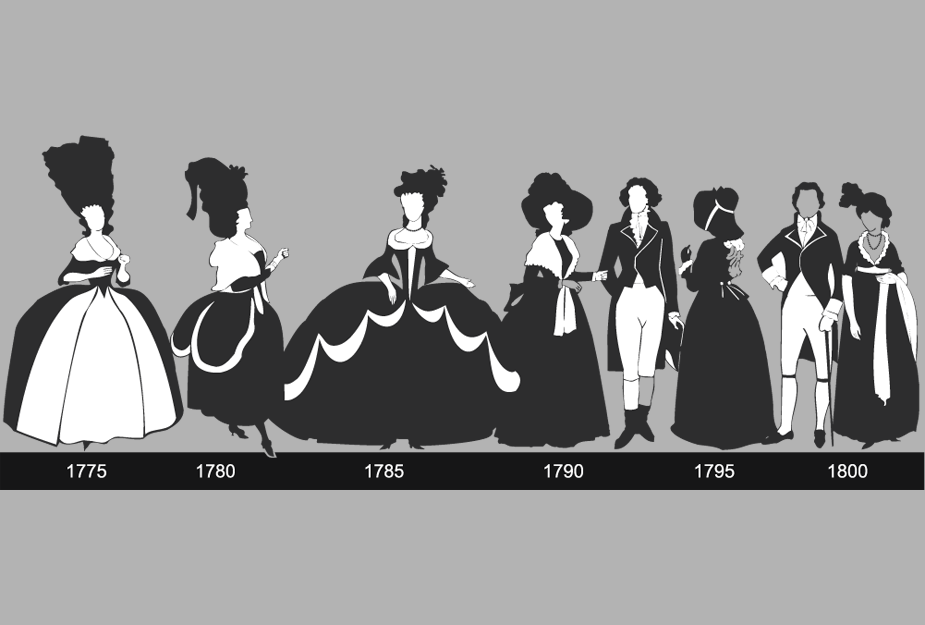

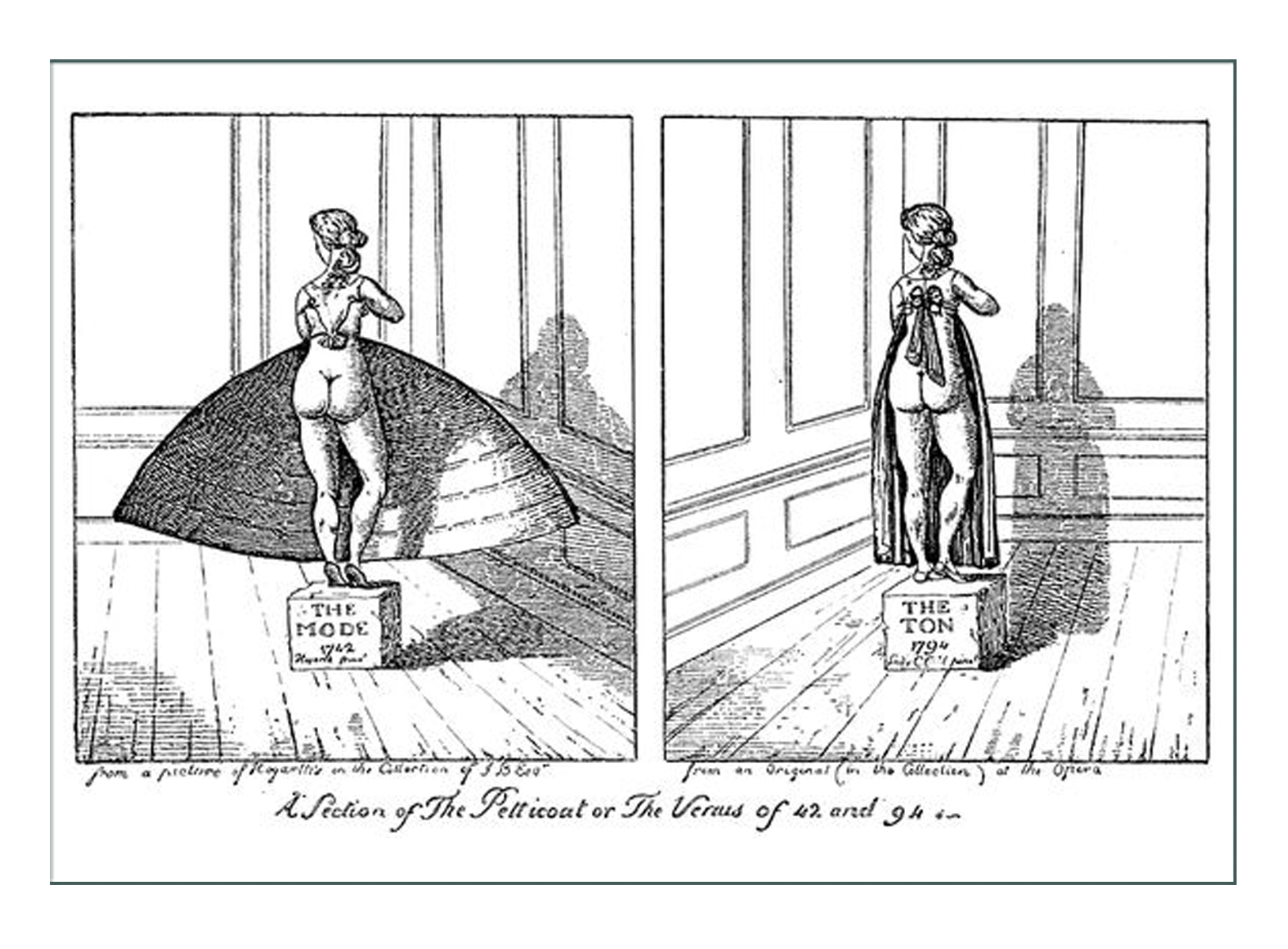

Waistcoat styles vary dramatically over the centuries with skirts and sleeves eventually being eliminated. Elaborate embroidery effects are common in the 18th century. In the late 19th century, vests designed for women became more common.

A knee-length coat with elbow sleeves, generally confined at the waist by a sash or buckled girdle, and always worn under a tunic or surcoat. This tunic and vest, mainly a court fashion in England, was the forerunner of the coat-and-waistcoat style and the origin of the man’s suit. 1

Colonial/Georgian Meets the French Revolution

Please see the Colonial Specific History Section and 1774 Sam Brito for Men’s Fashion History of the Colonial/Georgian Era

“A suit is a short, sleeveless bodice of varying design, worn with full evening dress.” 1

Despite horses being common throughout history as vehicles of war and trade, the frock was introduced due to the enhancement of comfort, convenience, and speed during equestrian sports. These activities were becoming more and more popular throughout England since King George III was a lover of horses and sporting events. Because of his interest, hunting and other equestrian activities quickly became a popular pastime amongst the elite. 10

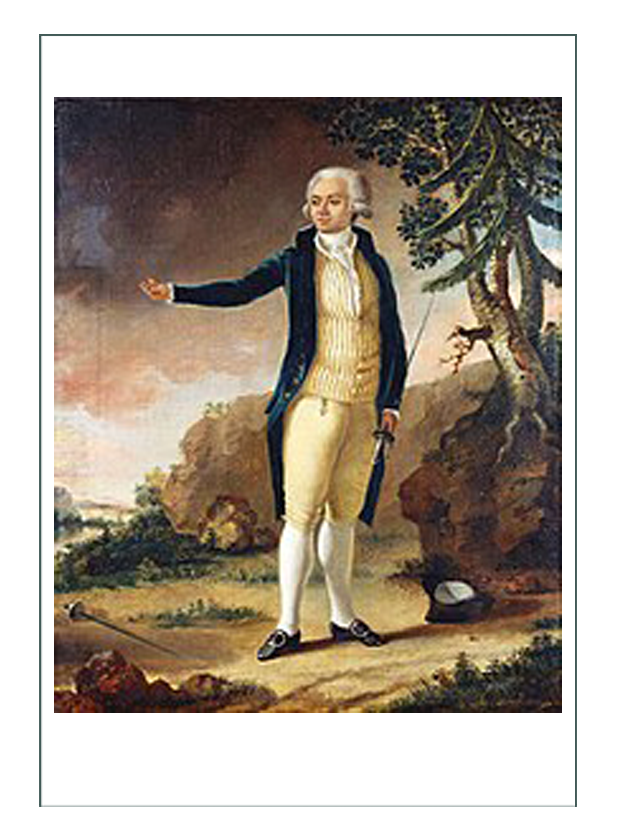

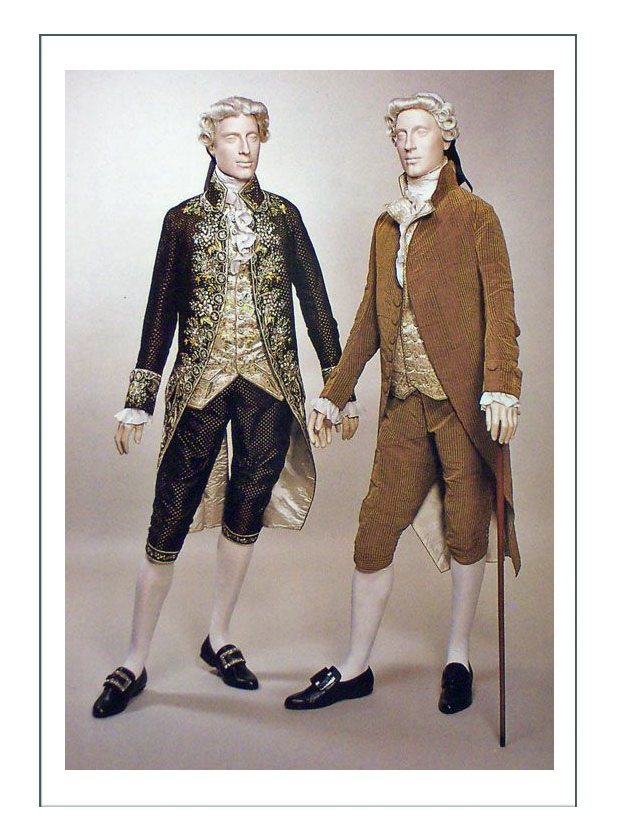

The historical precedent of peacocking was beginning to slow down as the century came to a conclusion. By the beginning of the Regency Era, the tailcoat had been adopted as the proper form of dress for fellowship in the evening hours. Elaborate cutaway coats slowly turned into a more understated and elegant coat as etiquette became more important within social groups. 10

In the 18th century, France ruled fashion because:

1) England followed France, & America followed England;

2) Trade & communication with other parts of the world was limited; e.g. Japan was an isolationist country until the end of the Shogun era;

3) France made great fabrics, laces, notions, & designs

4) The French, uninhibited compared to everyone else of Western society, went naked in public

By mid-century, fashion was largely the result of socio-political movements such as the French Revolution. At the time, class disparity was a big issue directing behavior and thus fashion of the day.

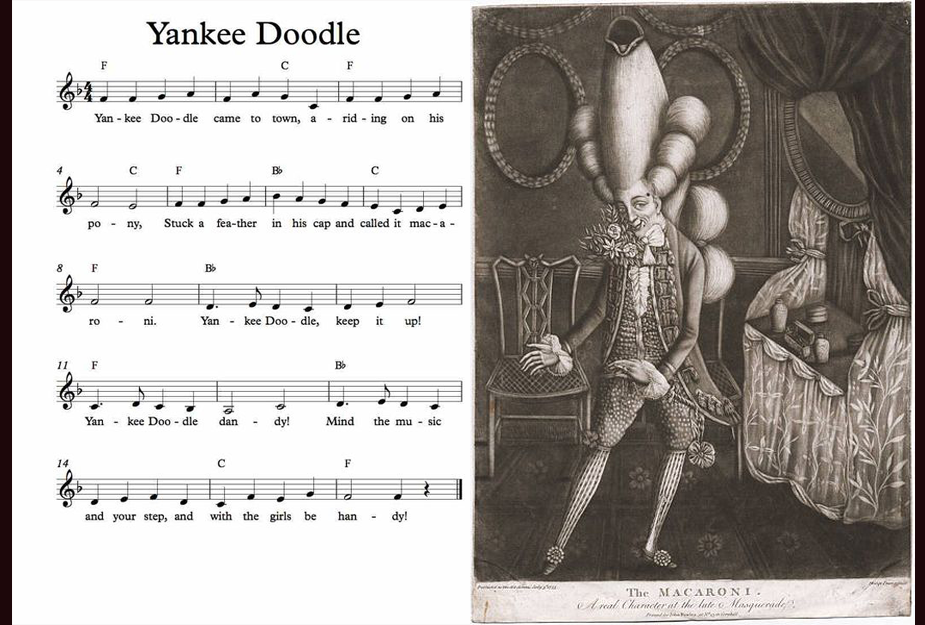

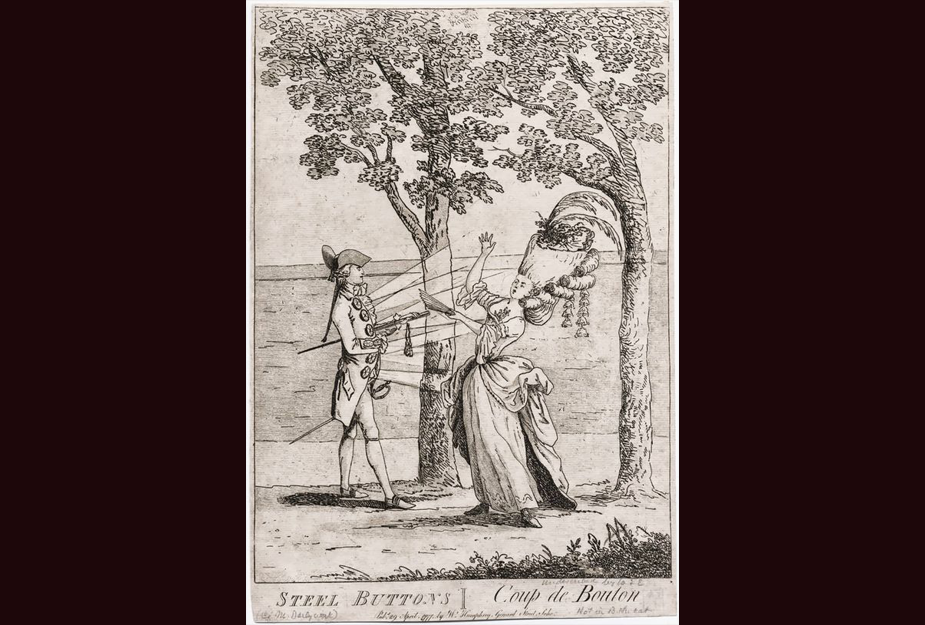

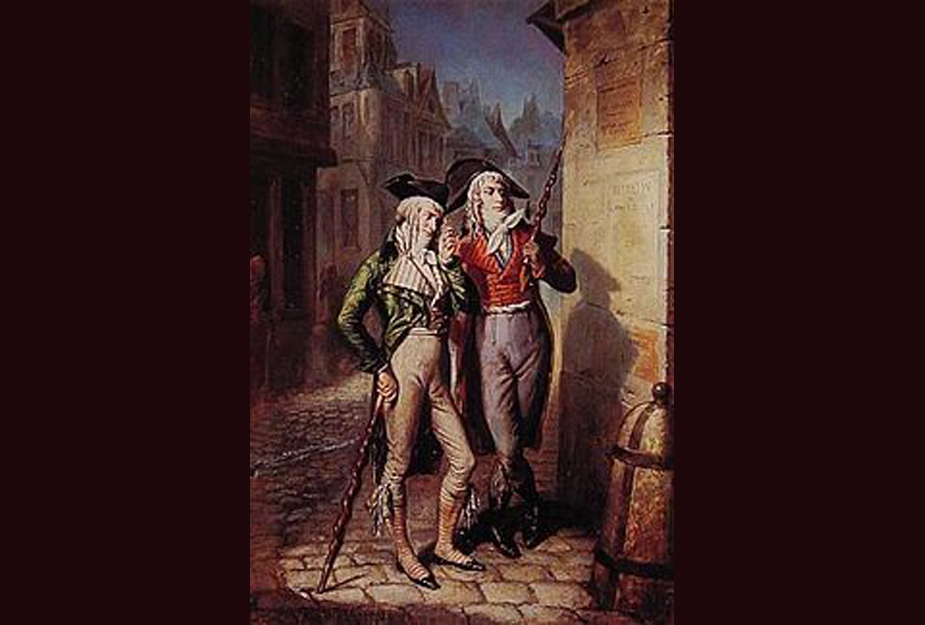

Muscadin was the derogatory name the lower classes gave to a group called the Incroyables, young bourgeouis men & women who dressed up in protest of the French Reign of Terror.Muscadins were also called Macarons, the original groups being street “dandyish” street gangs roaming Paris. They became known as the “White Terror”, a backlash against Jacobin oppression.They roamed the streets drinking, toasting the monarchy, & lashing out at patriots with sticks AND THEY LOOKED FABULOUS DOING IT.

The English counterpart, & having its root in the 1770’s, at the time America was in its Revolution were the “Dandies”

In fledgling 1770’s America, there were Dandies too… … young men & women were imitating the English & French “Dandies” in defiance of the political situation of the American Revolution.

It is not known if the American Dandy had a political statement to make, or if they just liked the freedom to wander about in weird costumes, hitting people with sticks.

While Dandies played at politics, Yankee Doodle stuck a feather in his cap.. … “and called it Macaroni”… American patriots were making fun of the British by referring to the British sub-culture of the Macarons & Muscadins when they sang “Yankee Doodle” & mimicked the aristocratic aires of the British nobility.

Beau Brummel

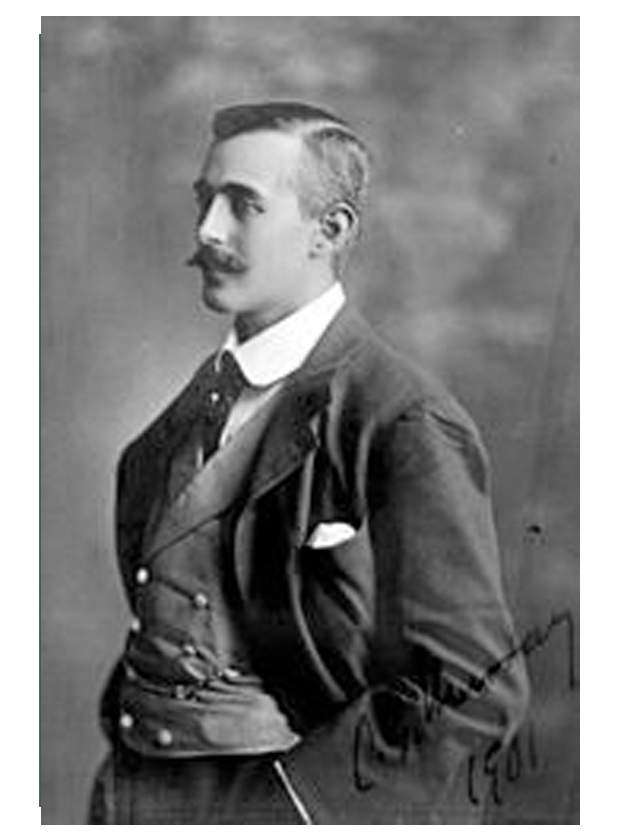

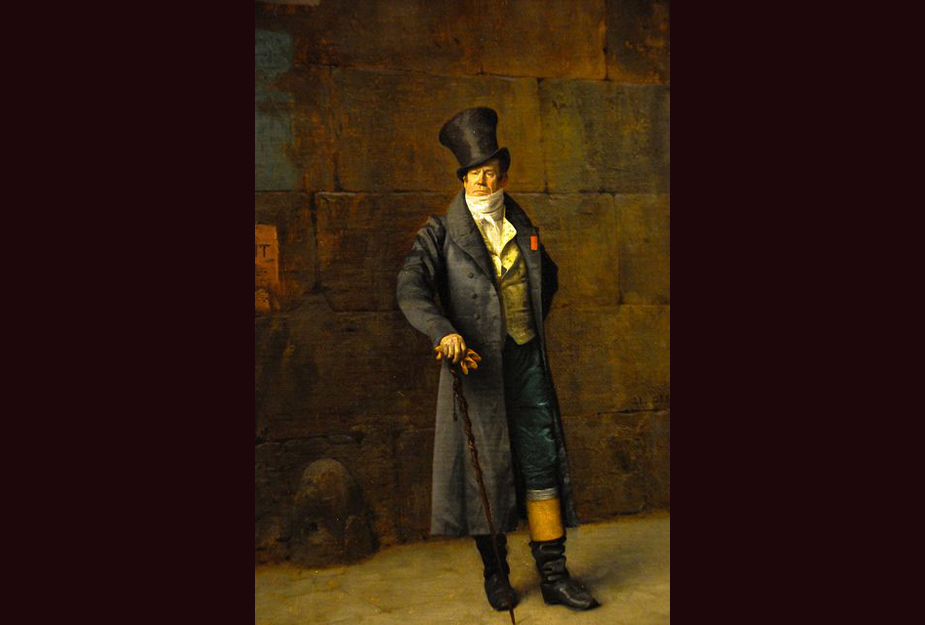

At the beginning of the 19th century, men’s style in England was basically a costumey nightmare: Well-heeled gents wore coats with tails, silk stockings, knee breeches (?!), and worst of all, powdered wigs. But then Beau Brummell came along and basically invented the suit we’re all still wearing today. 9

Enter Englishman Beau Brummel to London Society who boasted that he polished his boots with champagne.. George Bryan “Beau” Brummel was an iconic figure in Regency England, & a friend of the Prince Regent (the future King George IV).

Although Brummel didn’t have the financial means to dress as well, nor was it considered appropriate to try, his ingenuity and sense of style allowed him to modify less opulent apparel and turn them into exquisite outfits that were not only accepted but even mimicked by those who would otherwise not engage with a man of his stature. 10

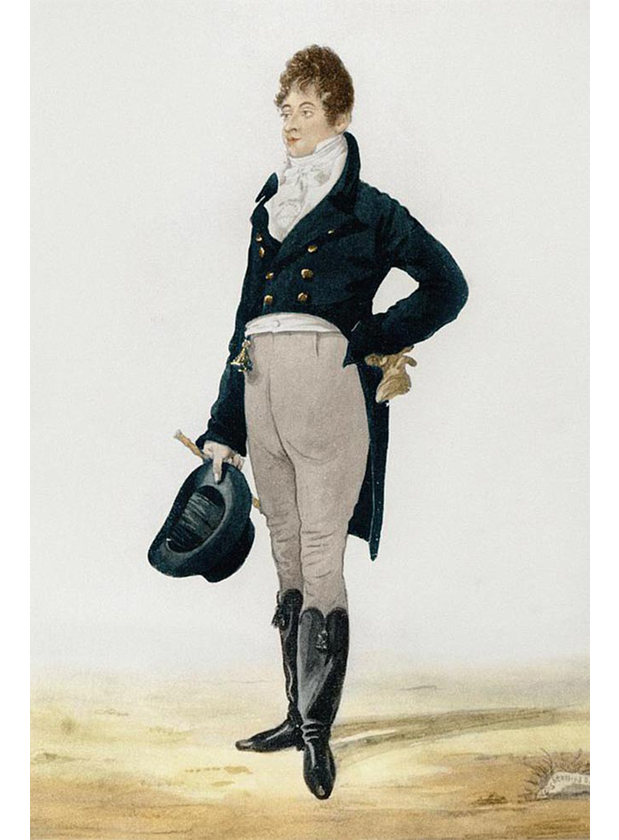

He was instrumental in replacing the bright and vivid opulence of clothing previously adopted from the French with a more refined and understated form of dress that is now synonymous with British bespoke style. The style was predominantly monochromatic and yet still quite in vogue. It focused on fit rather than trend and accentuated the gentleman’s masculinity by highlighting his physique rather than his accessories. 10

Beau Brummel was the 1775 founder of the “Dandies”, who established the mode of dress for men that rejected overly ornate fashions to one of perfectly fitted & tailored “bespoke” garments.

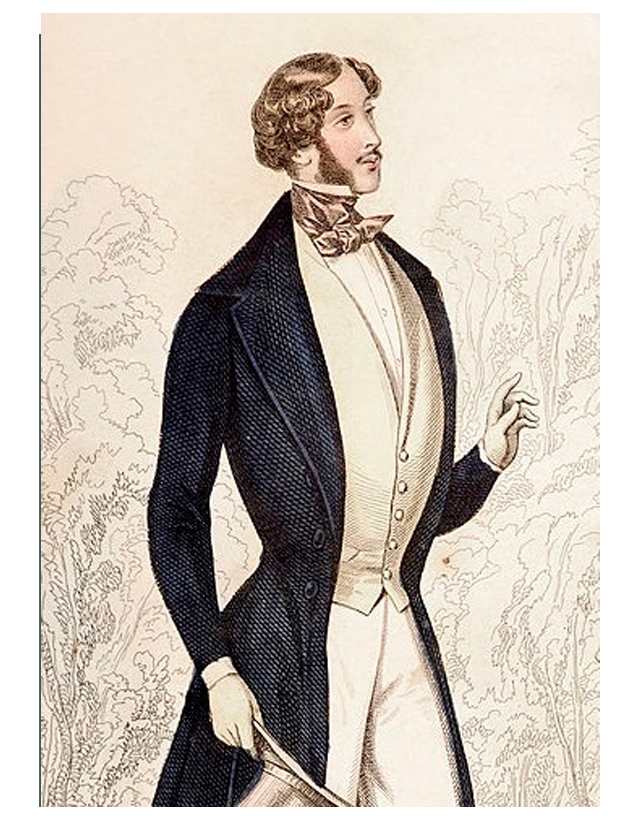

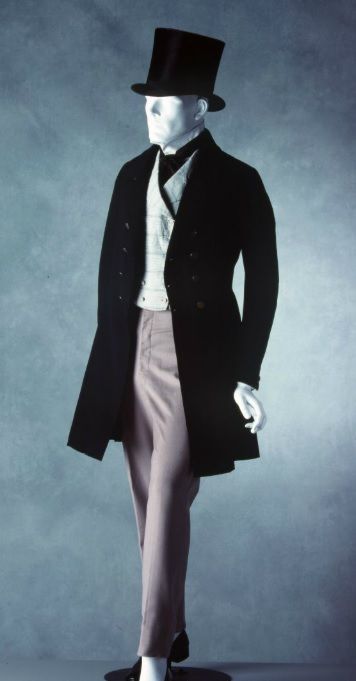

The look was based on dark coats, full length trousers instead of the knee breeches & stockings that dominated the day’s fashions, above all, an immaculate shirt linen with an elaborately knotted cravat (tie), which took 5 hours a day to get dressed in.

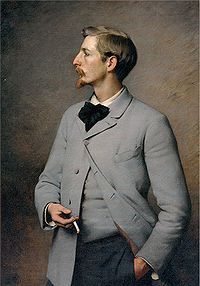

Beau Brummel in 1778 wearing his “cravat”; painting below: Jean Lerome, a later 1790 Muscadin, or Dandy, took fashion to a different level in introducing the long jacket & top hat. Combined with Brummel’s suit & tie, this concept would become the standard somber formal non-military “dress uniform” of men for decades to come.

Beau is attributed with the introduction of the modern men’s suit worn with a necktie, before he had to flee England to escape debt.

Regency Becomes Victorian

By the mid-1800s, the Industrial Revolution became one of the most important events to influence men’s fashion. Men wanted to appear as serious and solemn as possible. This required that those in the top ranks maintain a very classic appearance void of all embellishment and personality, not only at night but now during the day as well. 10

People were seen to be valued the same as we value businesses today. Based on what they could do for us, rather than honor or virtue. It didn’t matter if they gave an apple to a starving orphan. What mattered was if they owned a bank, if they could introduce us to a new prospect, or if they required a product or service we provided. The minimalism of a gentleman’s work attire was there to mimic his behavior at work and value. And his value as a man was based on the value he or his business could provide to others. Therefore, casual attire was reserved only for the privacy of his home, and he now wore his finest attire during the day, as well as at night. 10

History also gives us another important glimpse into how fashion developed in the 1800s. Throughout England, Freemasonry had grown from a small group of the most distinguished working masons into a fraternity of speculative masons who rapidly attracted the most elite members of society and even members of royalty. As a key practice, Freemasons would relinquish their social status at the door of the Lodge and, when meeting, would consider each other as fraternal brothers; as equals. To them, they all held the same status and class regardless of his rank and fortune outside of Masonry. What began at the door of the Lodge continued in the outside world. 10

Evening wear was a uniform of sorts, a standard outfit consisting of matching tailcoats that we know today as the white tie dress code. The tailcoat became the great equalizer and was adapted into the outside world. Etiquette was now prevalent not just as forms of chivalry towards women which existed for many centuries. But it was now a kind of common courtesy afforded to men within your inner circle. It required men to dress up when in the company of others. Attire was no longer primarily used as a means to peacock but was now a symbol of gallantry used to show others that their company was important enough to warrant a gentleman’s finest apparel. 10

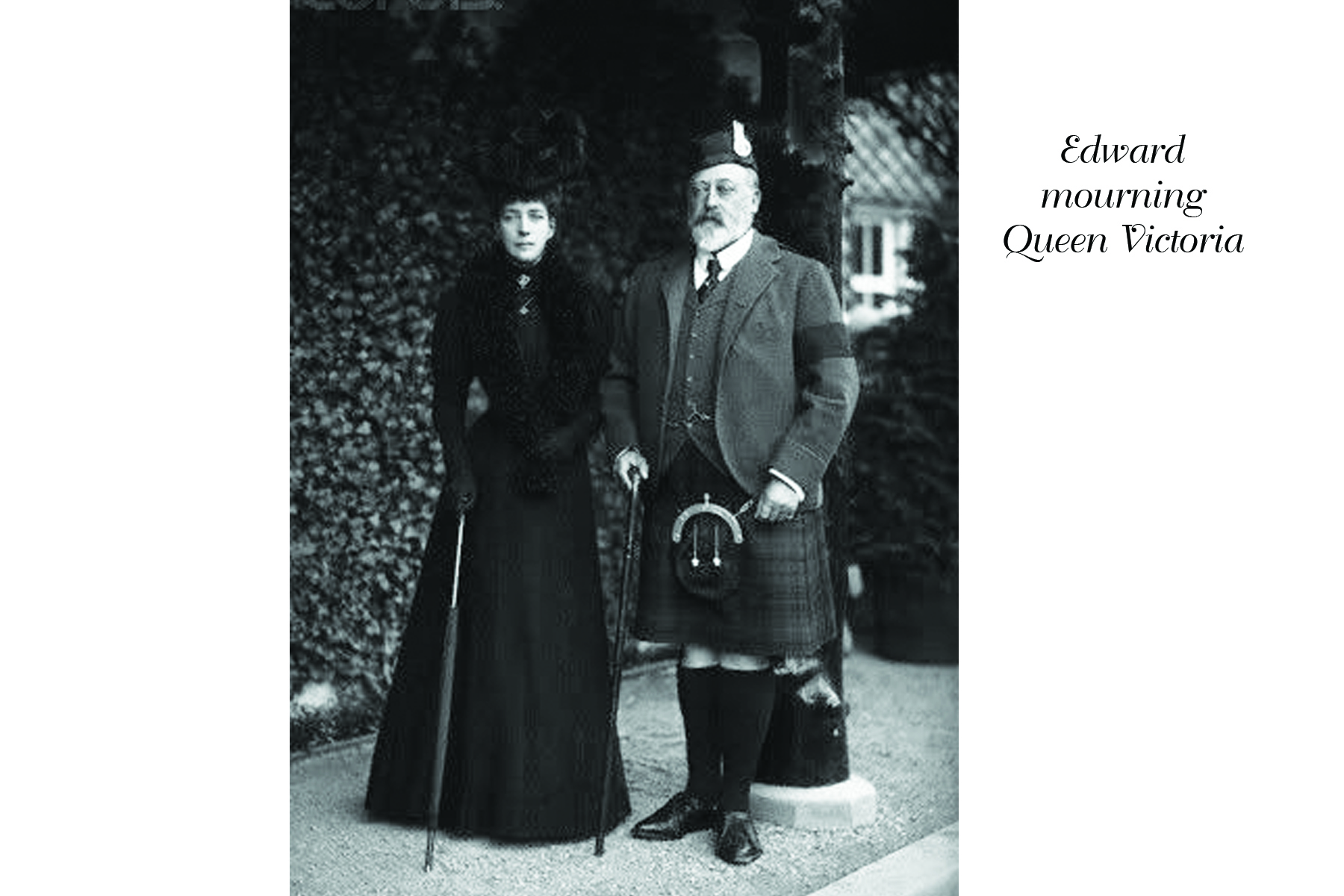

Historically, much of popular style was influenced by kings and imitated by his subjects. He was a man who could have anything he wanted in the world. And like today’s musicians and Hollywood celebrities, world leaders were revered and their styles imitated as the ultimate form of flattery. 10

With the invention of the automobile and the new ability to travel, for the first time in history, American fashion found its way to England. With it, came the dinner jacket, or tuxedo. Although the tailcoat and morning coat were favored by traditionalists, a younger and more modern generation was coming out of the woodwork and getting ready for the jazz age and the roarin’ twenties. 10

The tailcoat, which was initially reserved as the required evening attire, soon became formal evening attire. The dinner jacket was introduced for casual outings which were now far easier thanks to the motorcar. Now that a gentleman could come and go at his leisure without much regard for planning and having to pack luggage, convenience and comfort soon took center stage in many other aspects of everyday life. 10

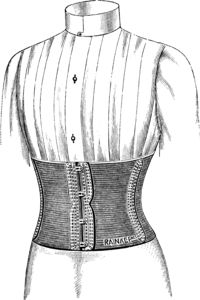

Synonymous with waistcoat; the American term is still “vest”. For women, the vest arrives later and takes several forms before resembling the menswear garment familiar today

Suit was also a term for the French long corset. “New invented Parisian vests…made of rich French Twillet, with double cased bones that will never break. The form of them is particularly elegant, by a Reserve on the peak…(which) has the pleasant and very essential effect of keeping the gores…in the proper position, and obviates that unpleasant rucking and chafing that is in all the long corsets that have been invented…”5.

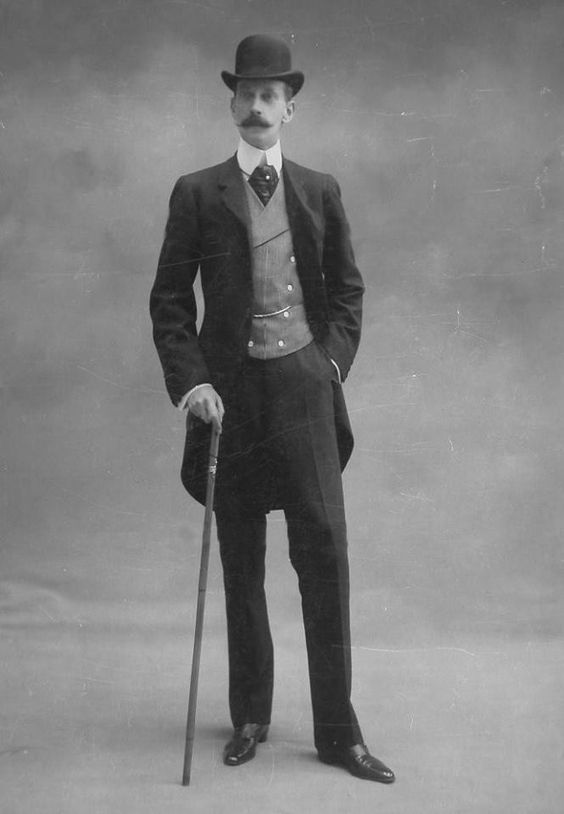

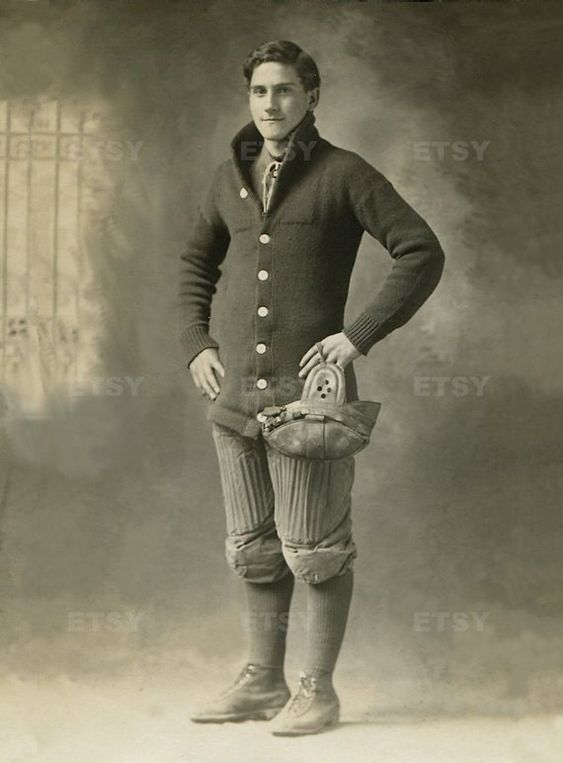

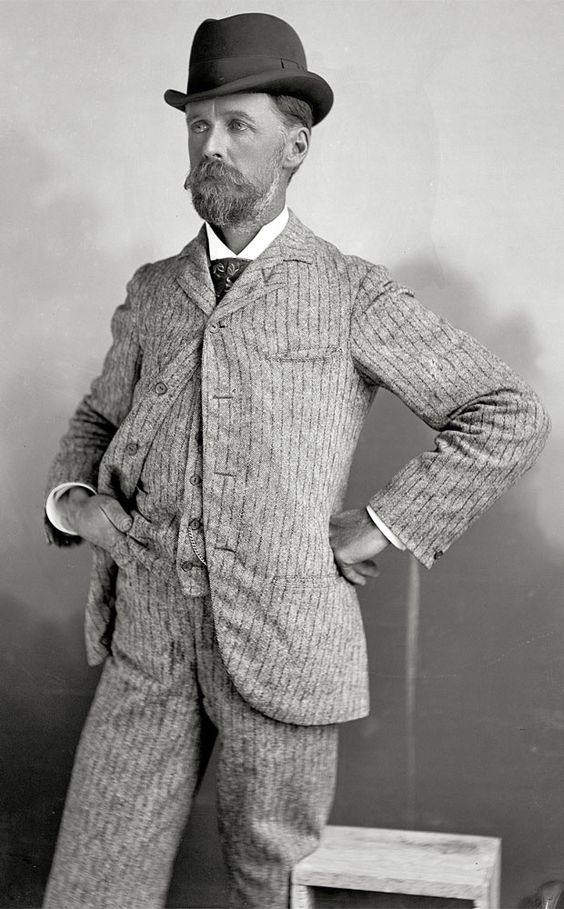

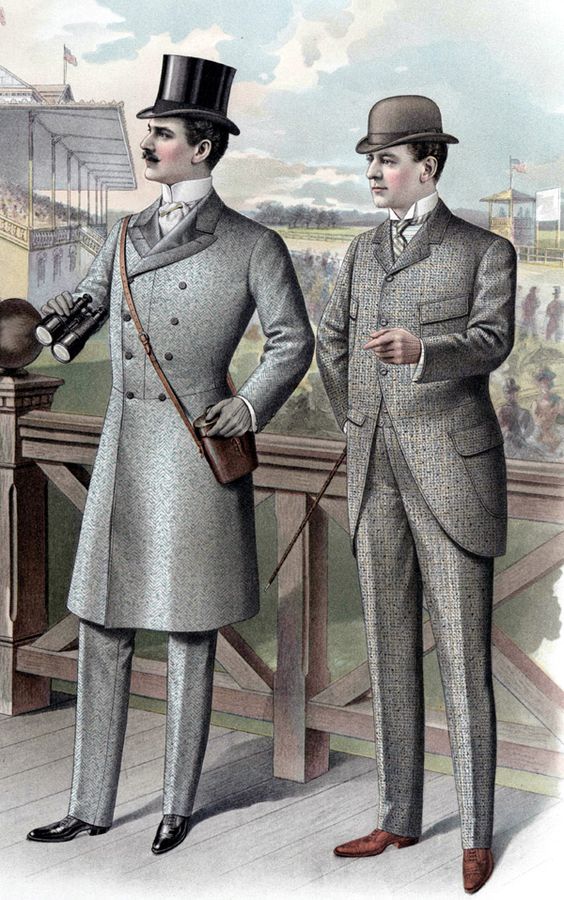

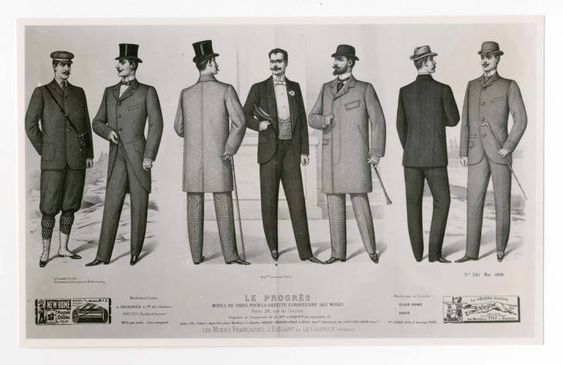

Suits around 1900 were defined by “dark colors, dark wovens, sturdy fabrics, and heavy woolens” for most men. Those in more fashion-forward cities like Paris and London added a little more flair to their get-ups than those Stateside, but the fit of everything remained basically constant across the Atlantic. High button-stances (often accompanied by the now unheard of four button jackets), slim lapels, unreasonably high arm-holes, and high paper shirt collars rounded out the look. Three-piece suits were prevalent, often with a double-breasted vest worn under the single breasted jacket (which would be a risky and somewhat ill-advised look today). 8

Specifics for the 1837-1901 Equivalent Time Frame

to Women’s Victorian Fashion Era

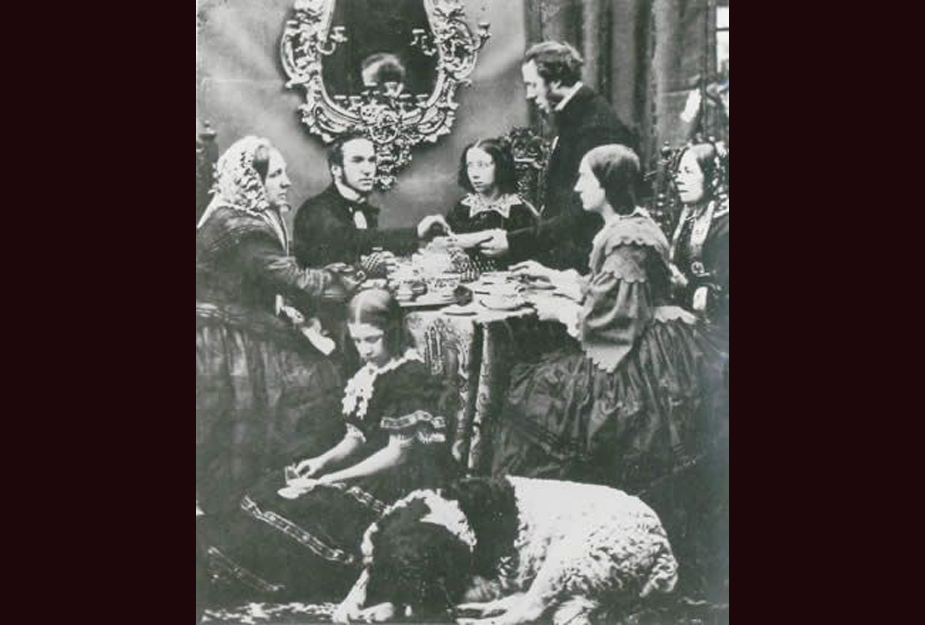

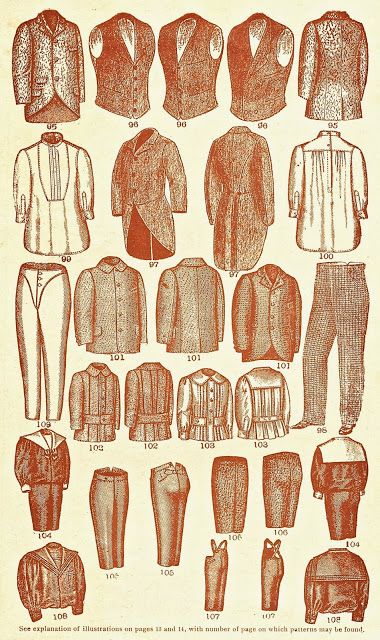

Men’s garments of the Victorian period have survived in far less quantity than women’s. Throughout the period, the dress of men was generally a suit composed of coat, waistcoat and trousers, not always of matching material. A coat or cloak was added for outdoor wear. At any time, two or three variations of each garment would be in general use for each occasion of wear. Then one variety would become dominant, the others continuing for some time as old-fashioned wear, or being relegated to a definite and more limited use. 4

Trouser Pants

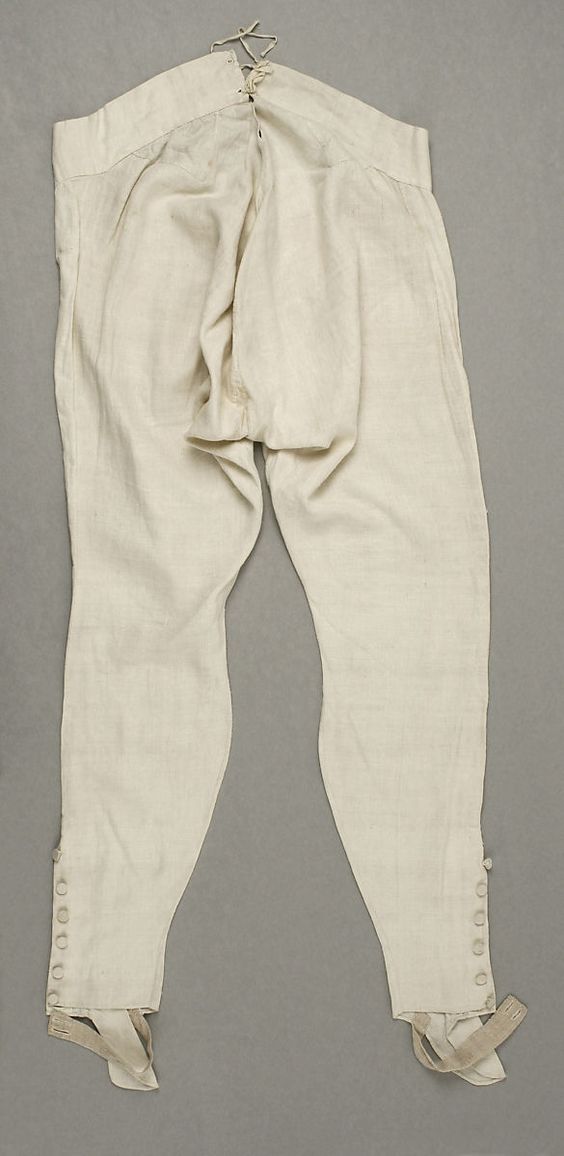

Of these garments, trousers are the rarest survivors. Waistcoats survive in quantity, coats are not scarce, but trousers are more rarely found. At the beginning of the period, trousers had just become well-established for general wear and breeches had almost disappeared, except for their survival in court dress and for riding.4

Pantaloons, which were tight-fitting garments reaching the calf or ankle, had been worn since the beginning of the century and were still worn, particularly with evening dress; but narrow trousers, with straps under the instep, were taking their place, and pantaloons were seldom worn after 1850. The straps under the instep also disappeared in the early 1850s.4

For most of the period the trousers were narrow, with slight variation of width, but in the late 1850s and early 1860s the “peg-top” trouser, wide at the top of the leg and tapering to the ankle, was a distinctive fashion. At the beginning of the period, a fall-front was still in use, but the fly front was becoming increasingly used, and was general by 1850.4

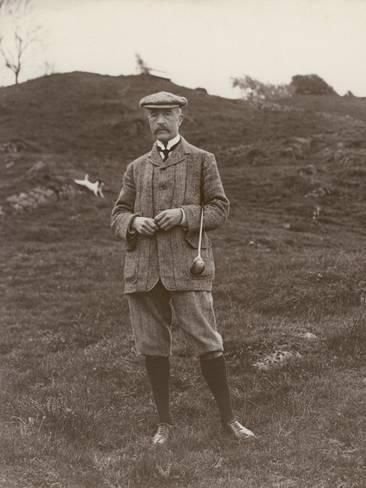

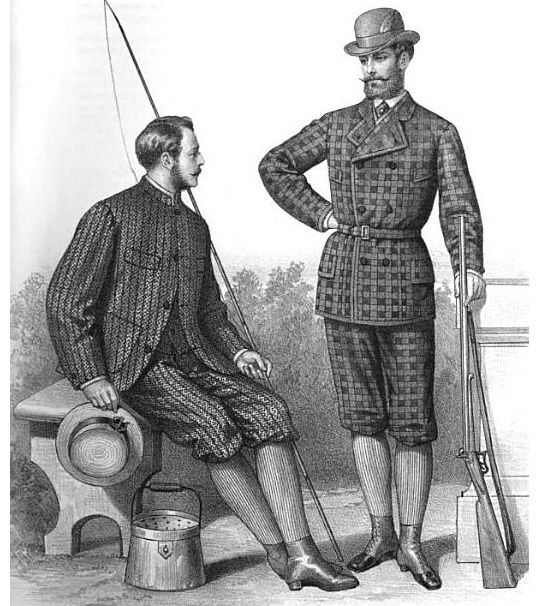

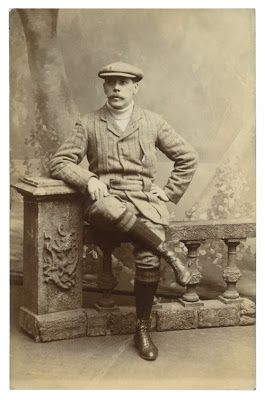

Knickerbockers, a loose form of breeches, appeared for sport and country wear in the 1860s and continued for this use until the end of the century.4

The pantaloons and trousers for evening wear at the beginning of the period were black cloth, and black trousers continued to be the only style for evening wear to the end of the century.4

For daytime wear the trousers were usually of a contrasting color to the coat; white, fawn or pale grey in a fine milled cloth were fashionable, and striped, checked and plaid materials for less formal wear. The stout cottons, nankeen and drill, were still used for summer wear, although they were less common after the middle of the century. The use of one material for coat, trousers and waistcoat appeared in the 1860s, particularly for the informal suit with the lounge jacket.4

Jackets, Coats

The frock coat was the usual coat form for day dress at the beginning of the reign. It was cut with a long waist and a short full skirt. It could be double-breasted or single-breasted. It was the dominant coat form for the 1840s and early 1850s and continued to be worn until the end of the century.

During the 1840s, its fastening rose higher, shortening the lapels. The double- notched “M” lapel went out of fashion on frock coats by about 1850. In the 1860s, there was less shaping for the waist, and the sleeves were wider at the shoulder, tapering towards the wrist. The sleeves thus repeated the line of the “peg-top” trousers and showed the same wide shaped form as women’s sleeves of the 1860s.

By 1870 they had lost the shoulder fullness and were less shaped, falling straight to the wrist, where the cuff became more defined, closing with two buttons. The waistline rose in the 1890s and the lapels lengthened.4

Although the frock coat was worn throughout the century, it lost its dominant position in the 1850s, when the morning coat began to replace it. A frock coat, with the skirt cut away in front in a curve from the waist, was worn as a riding coat in the 1830s and 1840s, and this shaping was adapted for a coat which gradually came into use as an alternative to the frock coat.4

A jacket shorter than the frock coat or morning coat appeared by about 1850. Unlike these coats, it had visible pockets. It was a garment of informal wear for country or seaside, and it became general in the 1860s. Like the frock and morning coats, it had a sleeve wide at the shoulder and a straight loose line. It was made in both double-breasted and single-breasted forms. By the end of the 1860s, this jacket had also become accepted for general daytime wear. A belted form, with the jacket cut full and pleated back and front, was fashionable for country wear and was known as the Norfolk jacket. In the 1880s, the single-breasted forms had rounded fronts, a shaping which continued until the end of the century.4

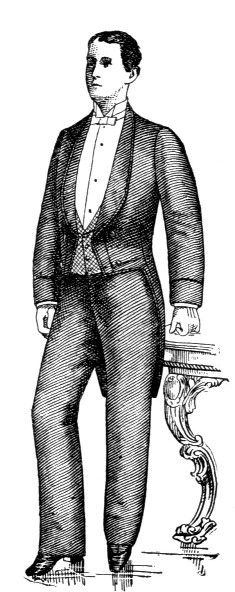

The tailcoat, with fronts cut away to waist level, which had been a style for both day and evening wear before 1830, had by the beginning of the reign become mainly a style for evening wear. It still appeared for formal daytime wear in the 1840s, but by 1860 it was an evening style only, and it remained the style of evening dress to the end of the century and beyond. It could be single- or double-breasted. The evening dress form had long lapels revealing much of the waistcoat; the day dress coat, for as long as it was worn, had higher buttoning. The lapels were notched and the double “M” notch continued in the evening coat into the 1860s. In the 1880s a style with roll collar appeared as an alternative to the separate collar and lapel, the roll collar curving low to reveal a large expanse of shirt front; both styles were worn in the 1890s. Sleeves wide at the top, and tapering to the wrist, also appeared in these coats in the 1860s.4

In the 1880s another type of coat appeared for the less formal evening occasions. It had the new roll collar of the tailcoat of this decade, and the short form of the lounge jacket which had been adopted for day wear. By the end of the century it was known as a dinner jacket.4

The evening coats were made of fine, milled cloth and from the beginning of the period were usually black or navy blue. Brown, dark green and mulberry color might still appear but, by 1860, a black tailcoats was the universal evening uniform. The frock coats were black, blue, brown or mulberry color, but by far the greater number of surviving examples are black or blue. Most are a finely milled cloth, but they were made in twilled and other cloth. The lounge jacket had a much wider range of materials, including the lighter worsteds and tweeds. Dark grey was popular during the 1890s for all coats but the evening coat. Velvet collars appeared on dress and frock coats, particularly before i860. A fine cord edging is characteristic of coats from the beginning of the reign to about 1850.4

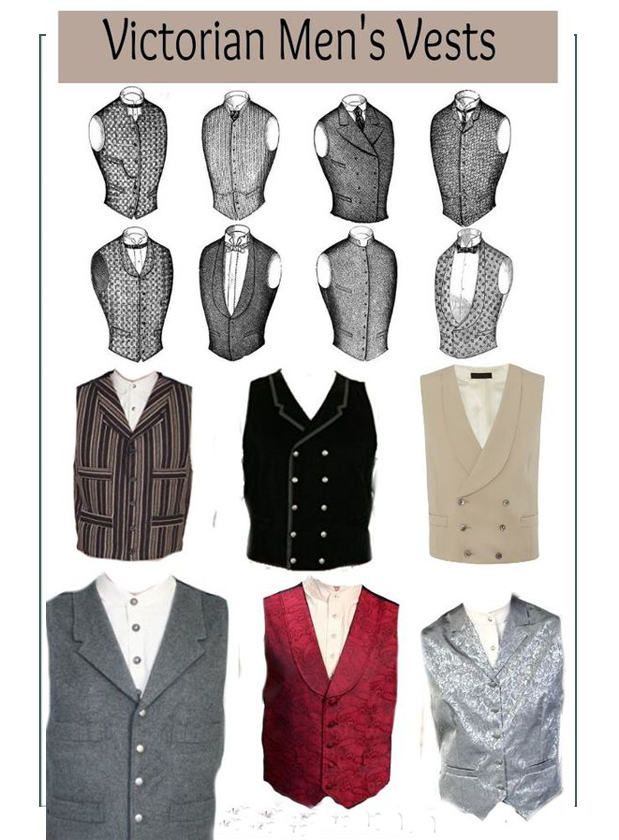

Waistcoats / Vests

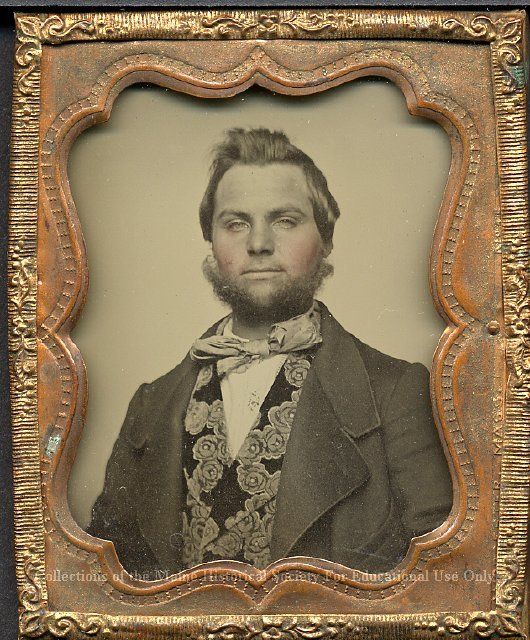

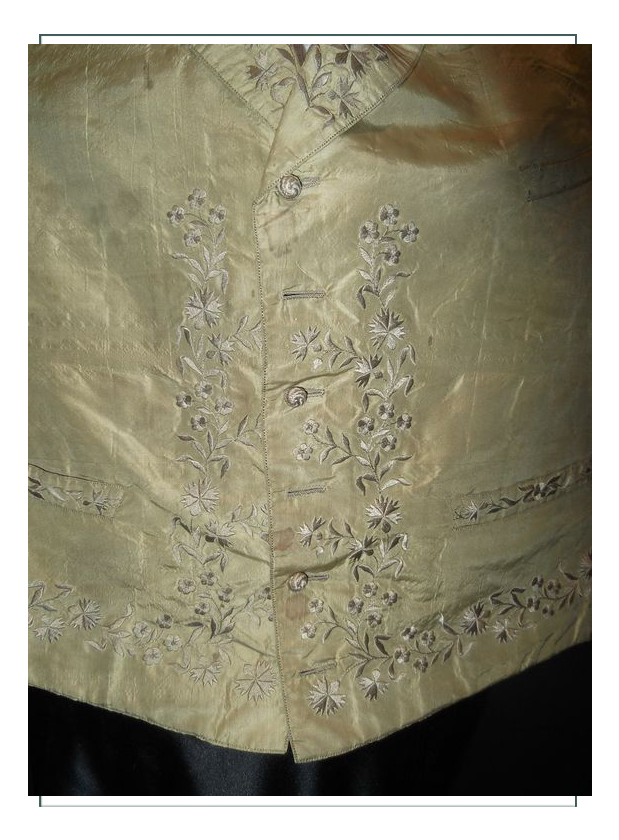

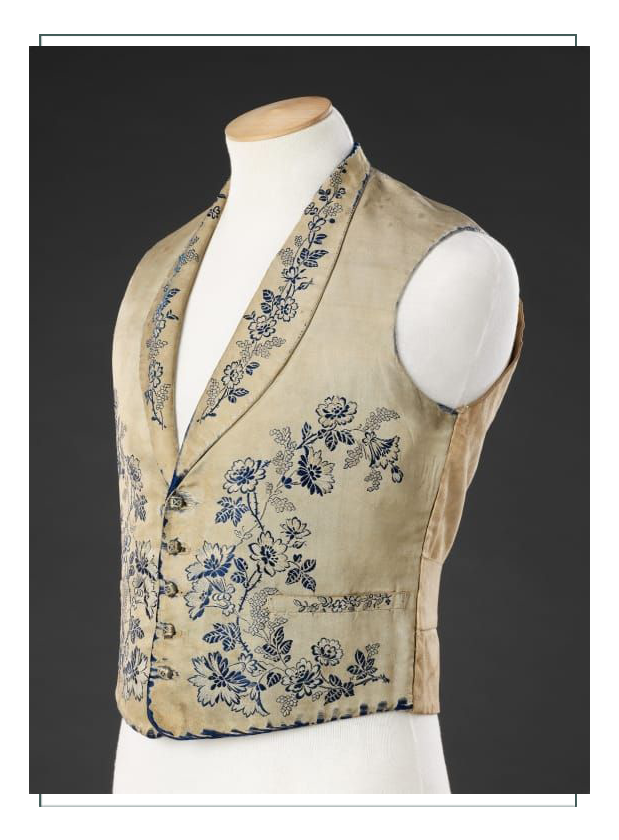

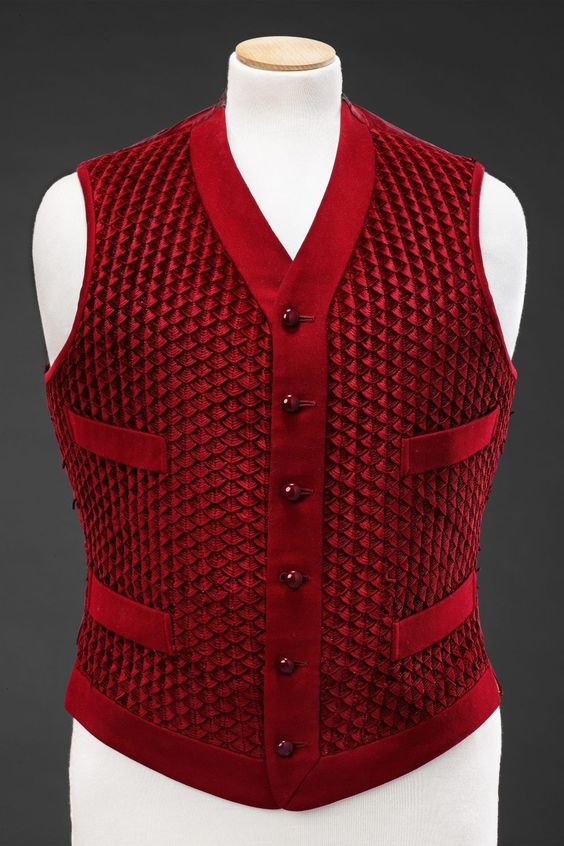

Most of the color and ornament of men’s dress was concentrated in the waistcoat, a garment which has survived in larger quantities than any other man’s garment of this period. Until the 1860s it showed the fabrics and colors and the woven and printed designs fashionable in the materials of women’s dress. The tradition of embroidery for waistcoats, much of it now by the amateur, continued.4

The type of fabric and the degree of ornament depended on the occasion of wearing, but until the 1860s the waistcoat was usually indefinite but harmonizing contrast to coat and trousers, not only in color but in the texture of its material. The higher fastening of coats, particularly the lounge jacket in the 1860s and 1870s, concealed much of the waistcoat, and this and the development of the wearing of coat, waistcoat and trousers of the same material, or coat and waistcoat alike with contrasting trousers, or trousers and waistcoat alike with contrasting coat, meant the eclipse of the waistcoat. “Fancy” waistcoats were revived in the 1890s, but beside the sure harmony or vivid splendor of the 1840s and 1850s their fancy appears hesitant and characterless.4

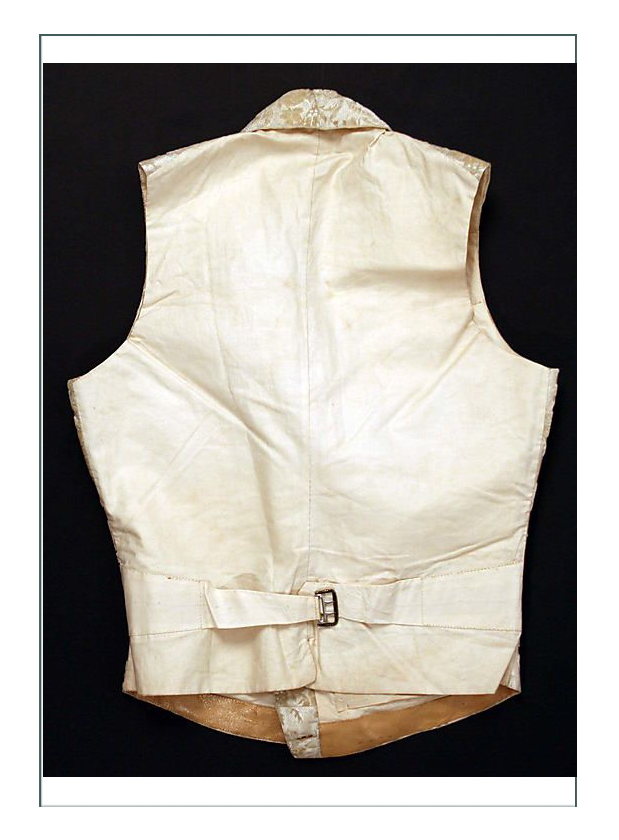

Many of the waistcoats which survive have been preserved because they were wedding waistcoats. These were often in white or cream figured silk, or white silk embroidered, although many examples have survived as wedding waistcoats which do not follow this fashion. For evening wear, also, the waistcoat was often white, in many different kinds of silk at the beginning of the period, but black evening waistcoats were fashionable in the 1860s and 1870s; only in the 1890s did white marcella or pique become the usual wear, the black waistcoat remaining with the dinner jacket.4

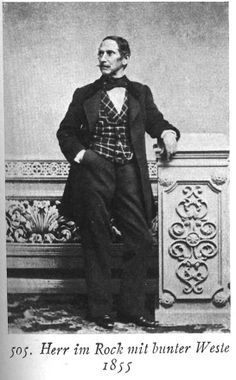

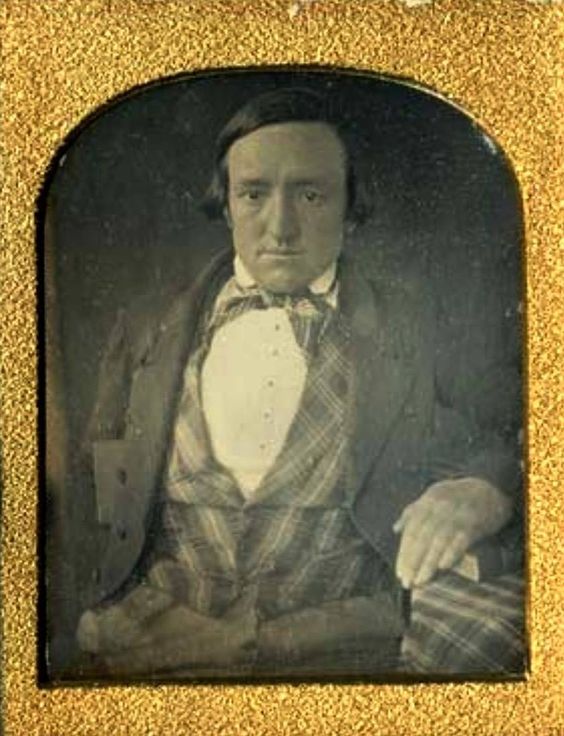

In the 1840s, the dress waistcoats of day wear and informal evening wear were in figured silks and satins very like the fabrics of women’s dress at the time. Plain silks and satins were embroidered, usually in a bordering pattern and on the pockets. At the beginning of the period, the liking for bright patterns on a dark background which appeared in women’s aprons, bags and shawls, appeared also in waistcoats, with cross-stitch patterns in brightly colored silks on a black or dark satin ground. Fine white or black twilled wool was also used and embroidered. 4

In the 1850s, there was an increasing fashion for tartan patterning in silk and velvet and the colors grew brighter in daytime wea. Although examples of dress waistcoats in figured velvets and similar materials survive from all periods up to the last years of the century, there was, after 1860, much less use of silk, particularly for daytime wear, and even when waistcoats did not match the cloth of coat and trousers, they were often in a woollen fabric with pattern limited to a fancy weave in a single colour.4

The waistcoats of the 1840s often show a pointed, rather long waistline. In the 1850s, the fronts were slightly cut away, a small triangular gap at the center waist. In the late 1860s, the waistline became shorter and the line at the waist was less pointed and nearer the horizontal. This movement of shortening and straightening at the waist kept in time with the more conspicuously changing line in women’s dress. The waistcoat lengthened a little in the 1870s and 1880s, but generally kept the horizontal line until the 1890s, when the day waistcoat again showed a small gap at the center waist.4

In the 1840s, the single-breasted form was general, although the double-breasted form appeared, particularly in plainer examples for daytime wear. For day wear, double-breasted forms increased in popularity during the 1850s and 1860s. The single-breasted form was more usual for evening wear throughout the period until the last years of the century, and particularly before 1870. For day wear, both types were worn to the end of the century. There were usually two pockets, sometimes three, until 1870; then three were usual and four occasional. Crescent-shaped pockets on waistcoats are usually a sign of an 1830s or 1840s date.4

The neck opening at the beginning of the period often had the collar continuous with the lapel, the opening being wide and deep; during the 1850s, the fastening rose a little higher and there were a larger proportion of waistcoats with a separate collar and lapel, the lapels often being wider and shorter; but the earlier form remained in fashion, particularly for evening wear. Waistcoats buttoning high, with or without a collar but without lapels, were worn in the 1860s. A deep opening appeared again in the 1870s, mainly in double-breasted styles. In the single-breasted styles, the fastening was higher and the collar and lapels were small, or there might be no collar. A higher fastening was general on all waistcoats in the 1890s except evening waistcoats, on which the opening widened and deepened in the 1880s and 1890s.4

Shirts

Linen shirts with a high collar and frilled opening were still being worn at the beginning of the period, and the frill remained on evening shirts until about 1850, when it was gradually replaced by a front section of vertical tucking or pleating, the opening being fastened by buttons or studs. This fastening was already used for shirts of day wear from the beginning of the period.4

A small frill sometimes remained around the vertical section containing the buttons and buttonholes, which was a decorative feature of shirts in the 1850s and 1860s. After 1870, shirt fronts became plain. Shirts with decorated fronts sometimes had a back fastening, and some a side fastening. After 1850, the corners of the shirt, where the seam opened at the base, were rounded. Striped cotton shirts were used for sporting and country wear from the beginning of the period, but not until the last years of the century were colored shirts accepted for formal day wear.4

The collar became lower during the 1840s and 1850s, when it began to turn down over the cravat. Detachable collars were worn from this time, and collar and cuffs and shirt front show an increasing stiffness in the second half of the nineteenth century. Collars with ends high in front were worn in the 1850s, but the collars of the 1860s and 1870s were low. They were now either single or double, the double being used only for daytime wear. The single collars were upright, with a gap at the center front, or with the corners turned down. After 1880, the collar in all forms grew higher and, for most of the 1890s, was between two and a half and three inches high. This high collar appeared in both men’s and women’s dress in the 1890s.4

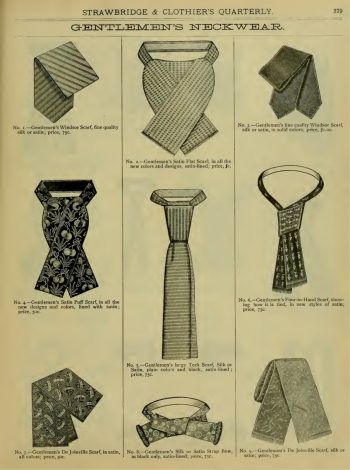

Ties and Suspenders

1830’s

In the late 1830s, the neckcloth or cravat was still a piece of white muslin, folded into a band, wrapped around the neck in front and brought from back to front again to tie in a great variety of knots. Black silk was becoming increasingly worn for daytime, and also colored silk both plain and figured. A stiffened, made-up band, with or without a bow in front, was also worn. It was then called a stock.

1840’s

By the end of the 1840s, white was unusual except for evening wear. After a period in the 1840s when black cravats were fashionable for evening wear, white remained usual for full evening dress for all the rest of the period, whatever the shaping of the cravat or tie. There was a change in the tying of the cravat in the 1840s, when the neckband was made narrow and the bow or knot very large. The cravat was sometimes knotted loosely as a scarf, fitting the opening of the waistcoat and fixed by a pin.

1860’s

By 1860, the collar of the shirt had become much lower and was turning down in front. The cravat was now a narrow band of material, usually less than an inch wide, tied in a small flat bow in front or knotted and fixed by a pin. These very narrow ties are characteristic of the 1850s and 1860s. The tie now made as a shaped band, narrow in the center for the neck, wider at the ends, was tied in a bow or knot during the 1870s and 1880s. In the 1890s, when the collar became higher, many varieties of knot and a great variety of materials were used in ties. 4

1840’s and ’50’s

At the beginning of the period the back of the waistcoat was usually tightened by tapes threaded through tabs sewn at the back. The tapes might be sewn d1rectly on to the waistcoat back, but this was a survival of the eighteenth-century style, which was going out of use by 1840. 4

Tabs which have metal eyelet holes all fall within the period. After 1845, the ties were being replaced by a strap and buckle, although the older method continued in use for many years. Leather facings were used at the base of the waistcoat fronts in the late 1840s and early 1850s. Darts under the lapels appeared mostly in waistcoats of the 1840s. The back and lining were usually of glazed cotton, but silk was sometimes used for evening waistcoats. Linings of striped cotton appeared in waistcoats for day wear from the 1860s. At the beginning of the period, and until about 1850, underwaistcoats were sometimes worn, to show at the opening of the waistcoat. These, which were a continued fashion from the 1820s and 1830s, were either collar and lapels only, or a short waistcoat.4

1850’s

Early 19th century men’s coats still had tails in the back, but were cut higher in the front. Some fashionable gentlemen wore corsets to give them a smaller waist. Men began wearing long trousers instead of knee breeches. Long trousers were at first used in the daytime. 6

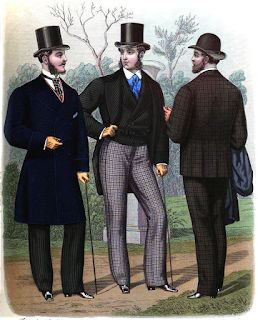

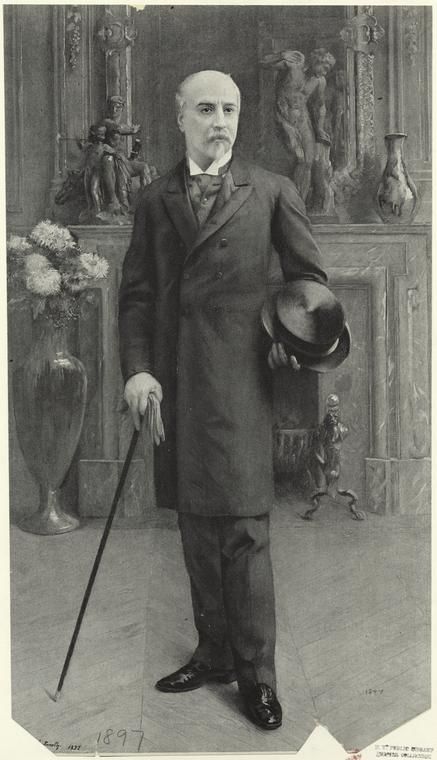

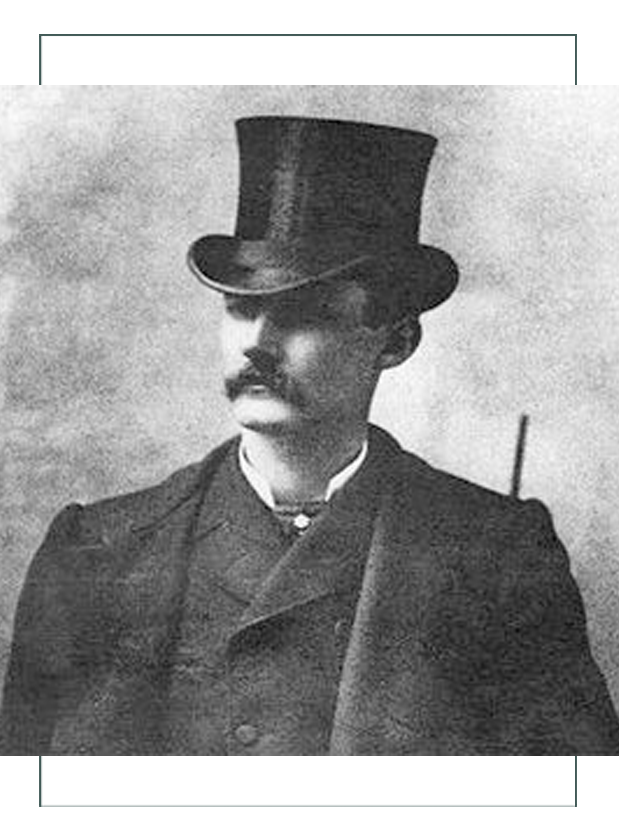

By 1850, men wore black tail coats and long trousers with a white waistcoat for formal evening dress. During the day, men often wore a frock coat cut at mid-thigh or knee length, a short waistcoat, long trousers and a shirt with a high, stiff collar. Men wore a tall top hat throughout the 19th century. 6

1870’s

Paris fashion of 1878 features a coat with a contrasting collar, a waistcoat decorated with a watch chain, wide ascot tie, square-toed shoes, and a top hat. 6

Innovations in men’s fashion of the 1870s included the acceptance of patterned or figured fabrics for shirts and the general replacement of neckties tied in bow knots with the four-in-hand and later the ascot tie. 6

Coats and trousers Frock coats remained fashionable, but new shorter versions arose, distinguished from the sack coat by a waist seam. Waistcoats (U.S. vests) were generally cut straight across the front and had collars and lapels, but collarless waistcoats were also worn. 6

Three-piece suits consisting of a high-buttoned sack coat with matching waistcoat and trousers, called ditto suits or (UK) lounge suits, grew in popularity; the sack coat might be cutaway so that only the top button could be fastened. 6

The cutaway morning coat was still worn for informal day occasions in Europe and major cities elsewhere. Frock coats were required for more formal daytime dress. Formal evening dress remained a dark tail coat and trousers. The coat now fastened lower on the chest and had wider lapels. A new fashion was a dark rather than white waistcoat. Evening wear was worn with a white bow tie and a shirt with the new winged collar. 6

Topcoats had wide lapels and deep cuffs, and often featured contrasting velvet collars. Furlined full-length overcoats were luxury items in the coldest climates. 6

Full-length trousers were worn for most occasions; tweed or woollen breeches were worn for hunting and hiking. 6

In 1873, Levi Strauss and Jacob Davis began to sell the original copper-riveted blue jeans in San Francisco. These became popular with the local multitude of gold seekers, who wanted strong clothing with durable pockets. 6

Shirts and neckties

The points of high upstanding shirt collars were increasingly pressed into “wings”. 6

Necktie fashions included the four-in-hand and, toward the end of the decade, the ascot tie, a tie with wide wings and a narrow neckband, fastened with a jewel or stickpin. Ties knotted in a bow remained a conservative fashion, and a white bowtie was required with formal evening wear. 6

A narrow ribbon tie was an alternative for tropical climates, and was increasingly worn elsewhere, especially in the Americas. 6

1880s

Coats, jackets, and trousers

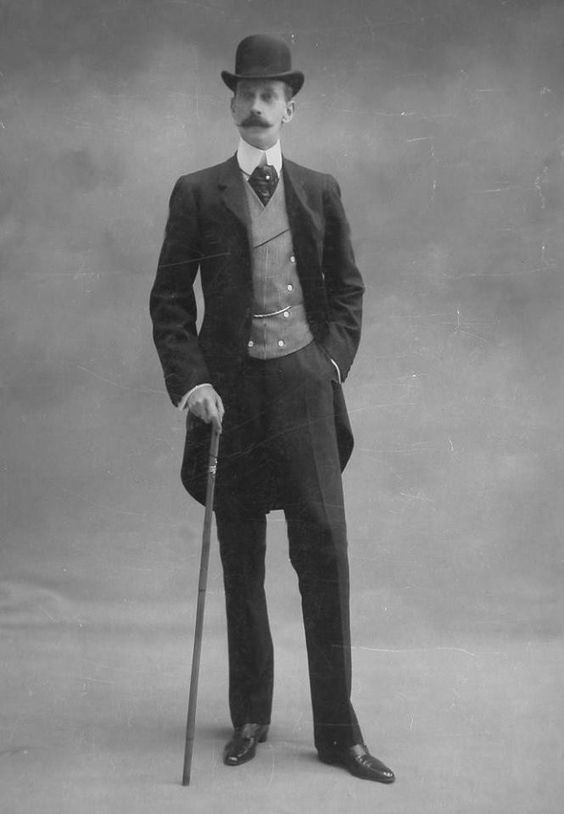

Three piece suits, “ditto suits”, consisting of a sack coat with matching waistcoat (U.S. vest) and trousers (called in the UK a “lounge suit”) continued as an informal alternative to the contrasting frock coat, waistcoat and trousers. 6

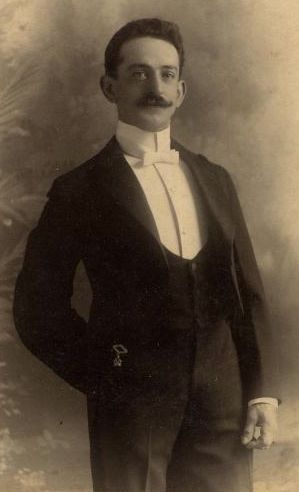

The cutaway morning coat was still worn for formal day occasions in Europe and major cities elsewhere, with a dress shirt and an ascot tie. The most formal evening dress remained a dark tail coat and trousers with a dark waistcoat. Evening wear was worn with a white bow tie and a shirt with a winged collar. 6

In mid-decade, a more relaxed formal coat appeared: the dinner jacket or tuxedo, which featured a shawl collar with silk or satin facings, and one or two buttons. Dinner jackets were appropriate when “dressing for dinner” at home or at a men’s club. 6

The Norfolk jacket was popular for shooting and rugged outdoor pursuits. It was made of sturdy tweed or similar fabric and featured paired box pleats over the chest and back, with a fabric belt. 6

Full-length trousers were worn for most occasions; tweed or woollen breeches were worn for hunting and other outdoor pursuits. 6

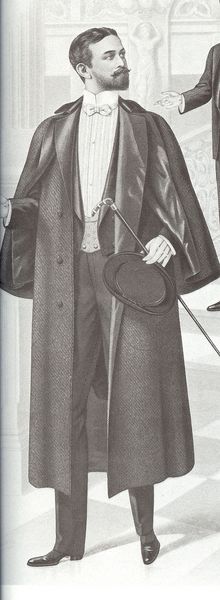

Knee-length topcoats, often with contrasting velvet or fur collars, and calf-length overcoats were worn in winter. 6

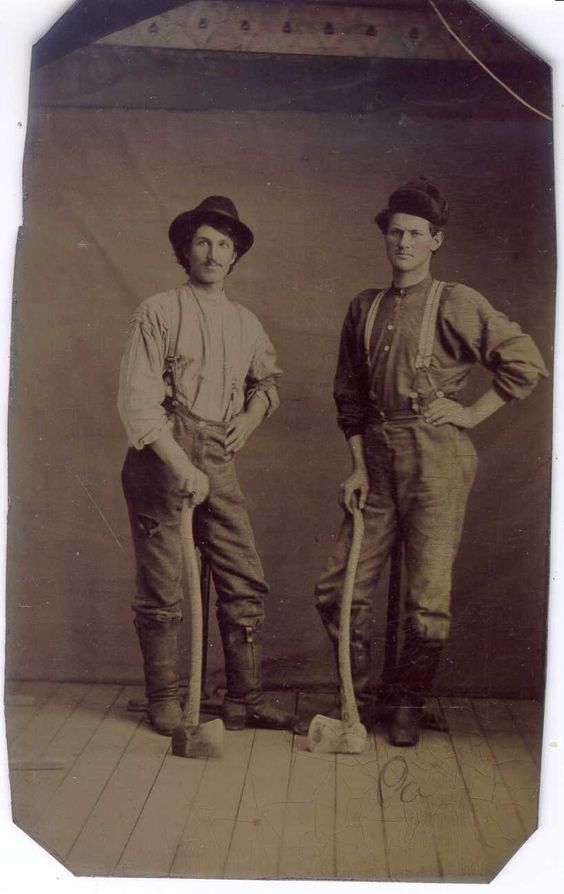

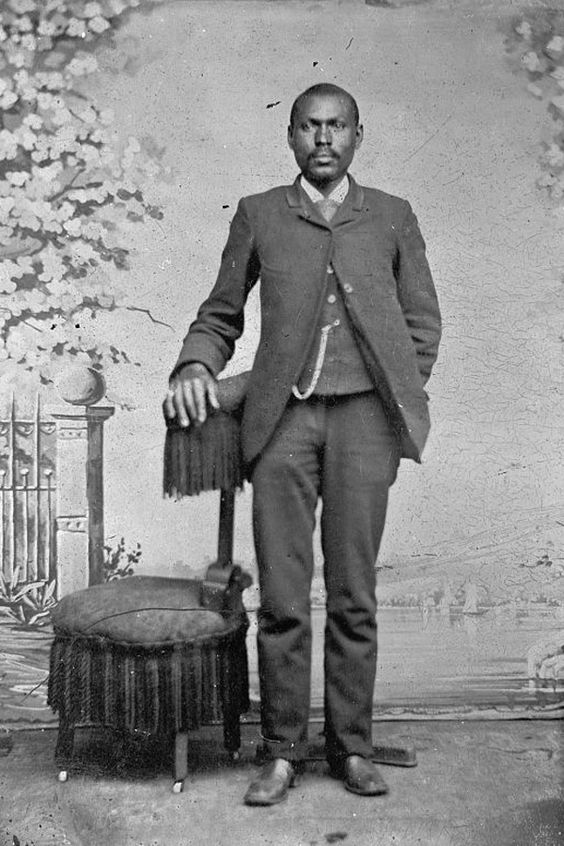

By the 1880s the majority of the working class, even shepherds, adopted jackets and waistcoats in fustian and corduroy with corduroy trousers, giving up their smock frocks. 6

Shirts and neckties

Shirt collars were turned over or pressed into “wings”. Dress shirts had stiff fronts, sometimes decorated with shirt studs, and buttoned up the back. 6

The usual necktie was the four-in-hand and or the newly fashionable Ascot tie, made up as a neckband with wide wings attached and worn with a stickpin. 6

Narrow ribbon ties were tied in a bow, and white bowtie was correct with formal evening wear. 6

1890s

The 1890s marked the beginning of the end for the Victorian Era, which had ruled society and fashion since the 1830s. Excitement and optimism could be felt as the 20th century neared, and a slight relaxation was felt in the world of men’s fashion. Even with a more relaxed feel for the time, the clothes would still be considered highly formal by today’s standards. 11

Day Suits

A man’s daytime suit in the 1890s would be considered appropriate for the most formal of occasions in modern day. Men wore vests, or waistcoats as they were known, and often had many of them in different colors and materials as a way to vary their work wardrobe. Pants worn for daytime had a high waist and were cut slim with a flat front, no pleats. They were often brown or grey or even patterned with stripes or checks. The Sack jacket was the popular coat to wear for daytime in the 1890s, a shorter cut that ended at the hips and was all the rage. 11

Evening Wear

The Victorian Era gave men reason to dress in formal evening wear quite often. Dinners, dances and cultural events called for full formal attire. Men wore what would be considered a tuxedo by modern standards simply to go to dinner. Frock coats were seen often at the time, long jackets that went to the knee in front and back. Tail coats were also worn, which were short in front and long in back. Waistcoats were always worn beneath, and would hold the man’s pocket-watch. For formal occasions, men wore white gloves. Men wore long overcoats in cold weather during the day or night, or wore black capes at night. 11

Ties, Collars and Shoes

Ties in the 1890s were rather bland compared to today, usually black. The pop of color in a man’s wardrobe was accomplished with his waistcoats rather than his ties. Ties were often silk and could be worn long or short for daytime. Evening ties were usually ascots or bow ties.11

Stand-up shirt collars were often worn at the time, especially with formal evening wear. Collars buttoned to the shirt and could be removed for cleaning. Hats were a staple in a man’s closet; derbies and bowlers were seen for daytime wear during the 1890s, while top hats remained the most commonly worn for evening. 11

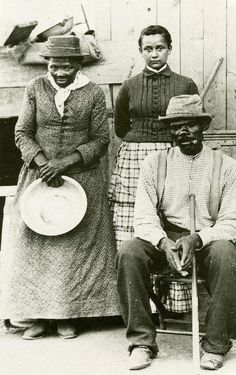

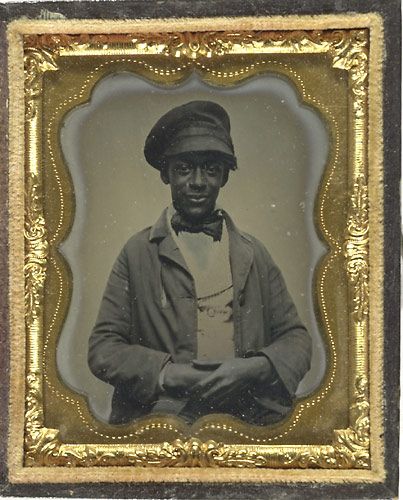

Laborers and Farmers

Men who labored for a living and did not work in an office had no use for a suit during the daytime. These men wore flannel, linen or cotton shirts and pants that were sturdy and tough, made from wool, denim or corduroy. Pants were held up by suspenders, or bracers as they were called at the time, not belts. Laborers still wore hats; the peaked cap was one style worn by workers. These men did own suits, and would wear a suit with a vest to social outings such as church or dances. 11

Men’s fashion

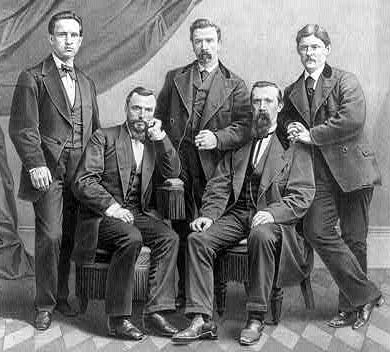

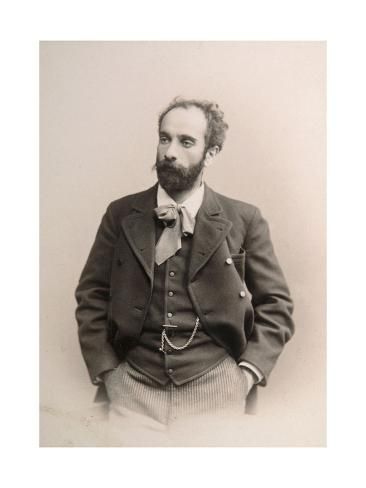

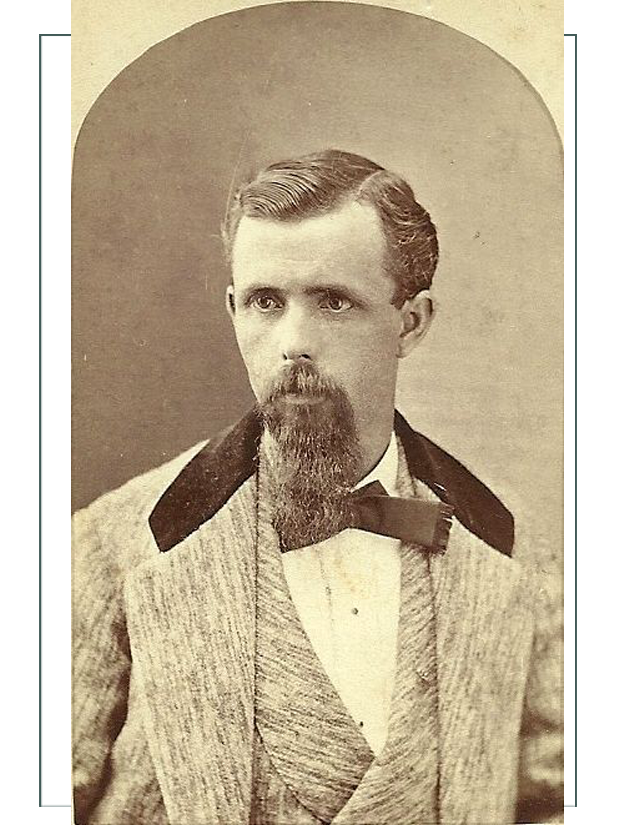

Early 1890s fashion includes gray coat with covered buttons and matching waistcoat, dark trousers, short turnover shirt collar, and floppy bow tie. The short hair and pointed beard are typical. 6

The overall silhouette of the 1890s was long, lean, and athletic. Hair was generally worn short, often with a pointed beard and generous moustache. 6

Coats, jackets, and trousers

By the 1890s, the sack coat (UK lounge coat) was fast replacing the frock coat for most informal and semi-formal occasions. Three-piece suits (“ditto suits”) consisting of a sack coat with matching waistcoat (U.S. vest) and trousers were worn, as were matching coat and waistcoat with contrasting trousers. Contrasting waistcoats were popular, and could be made with or without collars and lapels. The usual style was single-breasted. 6

The , a navy blue or brightly colored or striped flannel coat cut like a sack coat with patch pockets and brass buttons, was worn for sports, sailing, and other casual activities. 6

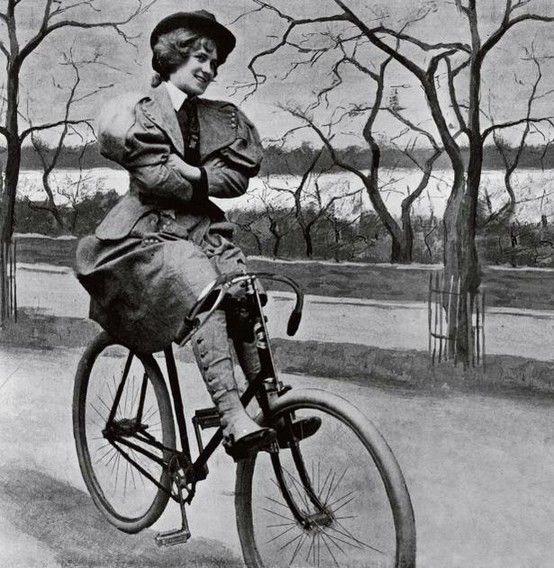

The Norfolk jacket remained fashionable for shooting and rugged outdoor pursuits. It was made of sturdy tweed or similar fabric and featured paired box pleats over the chest and back, with a fabric belt. Worn with matching breeches (or U.S. knickerbockers), it became the Norfolk suit, suitable for bicycling or golf with knee-length stockings and low shoes, or for hunting with sturdy boots or shoes with leather gaiters. 6

The cutaway morning coat was still worn for formal day occasions in Europe and major cities elsewhere. 6

The most formal evening dress remained a dark tail coat and trousers with a dark or light waistcoat. Evening wear was worn with a white bow tie and a shirt with a winged collar. 6

The less formal dinner jacket or tuxedo, which featured a shawl collar with silk or satin facings, now generally had a single button. Dinner jackets were appropriate formal wear when “dressing for dinner” at home or at a men’s club. The dinner jacket was worn with a white shirt and a dark tie. 6

Knee-length topcoats, often with contrasting velvet or fur collars, and calf-length overcoats were worn in winter. 6

Shirts and neckties

Shirt collars were turned over or pressed into “wings”, and became taller through the decade. Dress shirts had stiff fronts, sometimes decorated with shirt studs and buttoned up the back. Striped shirts were popular for informal occasions. 6

The usual necktie was a four-in-hand or an Ascot tie, made up as a neckband with wide wings attached and worn with a stickpin, but the 1890s also saw the return of the bow tie (in various proportions) for day dress. 6

Western & Rural Variations on High Fashion

The Shirt

The western shirt, characterized by a yoke and elaborate decorative additions including embroidery and piping, has become a staple of modern western wear. The yoke, first appearing in the 1800s, is a shaped piece of the garment that is situated around the neck and shoulders to provide support for the looser parts of the shirt and is sometimes defined by a contrasting color or pattern. It wasn’t until the Western films of the 1950s, however, that the modern western shirt became popular – usually produced in bright patterns with snap pockets, long sleeves, patches, and sometimes fringe. Inspired by the elaborate Mexican vaquero wear and the battle shirts of Confederate soldiers, the modernized cowboy shirt was worn by rodeo cowboys so that they could be easily identified – they were also popular everyday dress for teenagers in the 1970s and 2000s.6

The Trousers

In the early days of the Wild West, the most common type of pants were wool trousers, or canvas trousers during the warmer months. During the Gold Rush of the 1840s, denim overalls became favored by miners for its cheapness and breathability, and Levi Strauss, building on the demand, improved the denim look by adding copper rivets

.

By the 1870s, ranchers and cowboys adopted this pant for everyday use, with many other jean companies emerging in the wake of its popularity – such as Wrangler and Lee Cooper. Today, it’s still the most prominent choice for western wear, usually with added accessories like belts, large buckles, and metal conchos.6

First appearing in the late 19th century, leather chaps – skintight shotgun chaps or wide batwing chaps – were worn over trousers to protect the cowboys’ legs from sharp plants, such as cacti, and to prevent the pants from wearing out too quickly.

Chaps were typically made from tanned leather; however, in the late 1860s, vaqueros from California brought ‘woolies’ – chaps with the hair left on – to the northern cowboys during a cattle drive to the mines in Montana. These quickly became a part of the cowboy culture after ranchers discovered how these would protect cowboys from the cold of winter. Today, rodeo cowboys wear embellished chaps in bright colors to draw attention while they demonstrate their skills.6

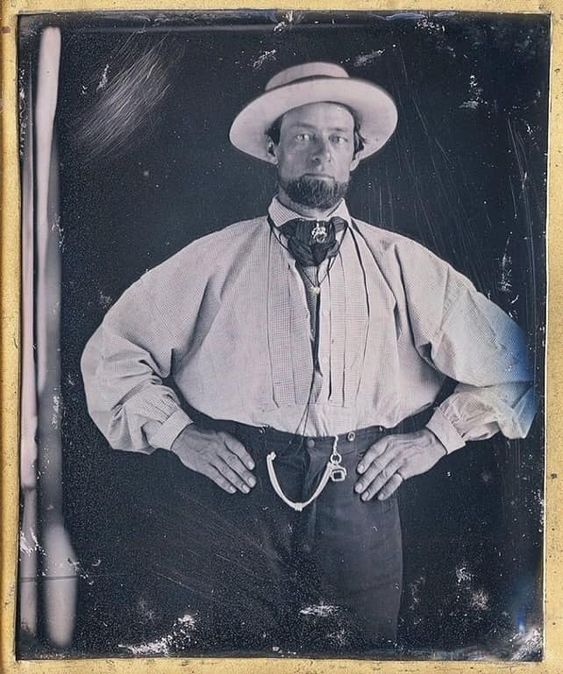

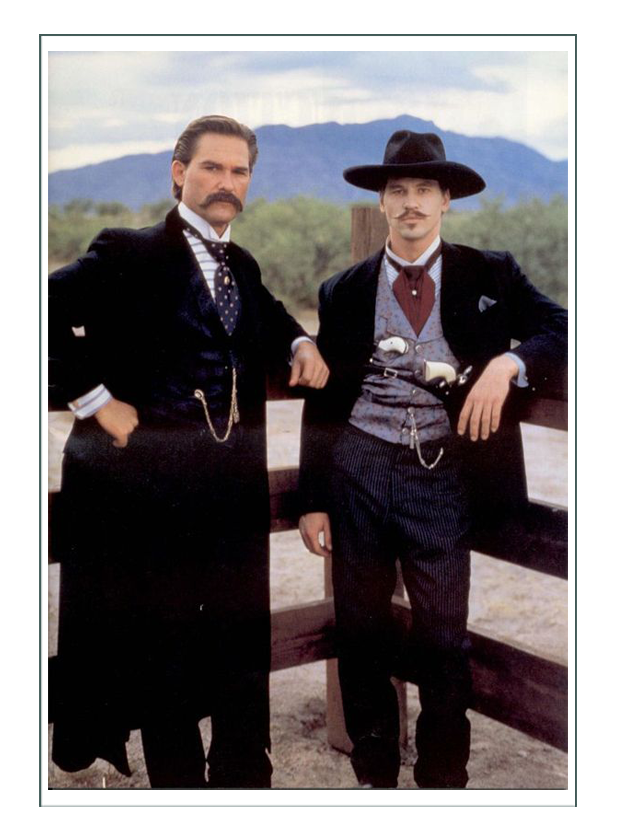

What Would Wyatt Wear?

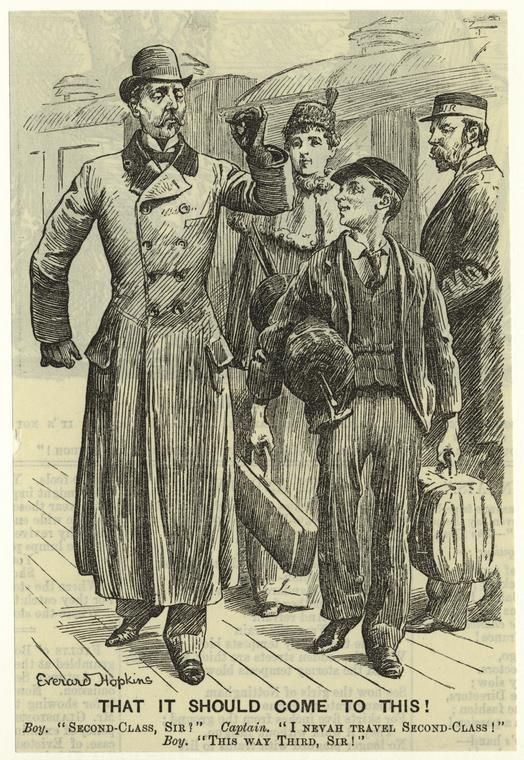

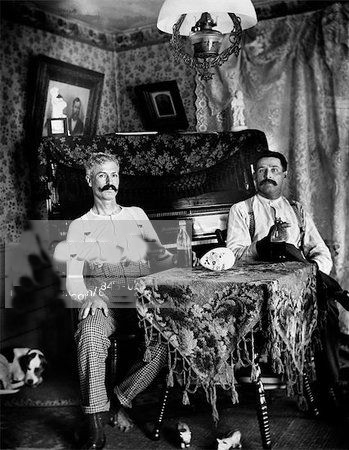

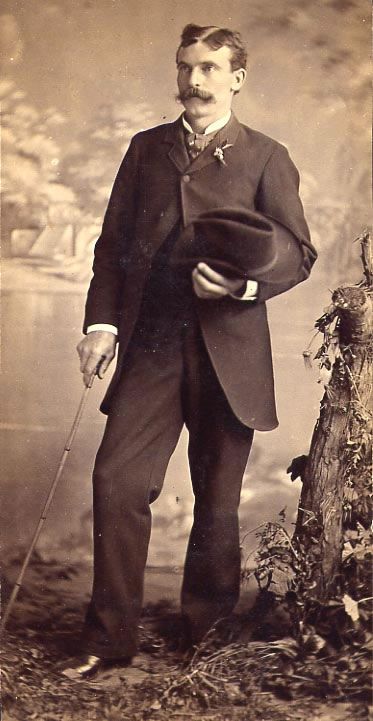

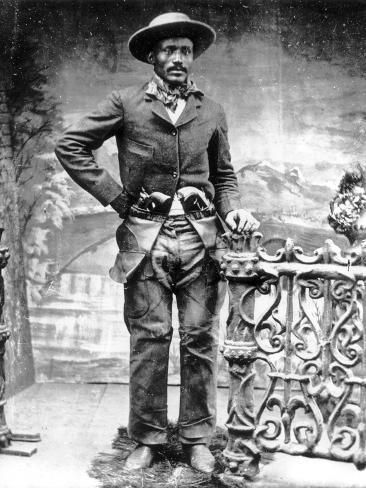

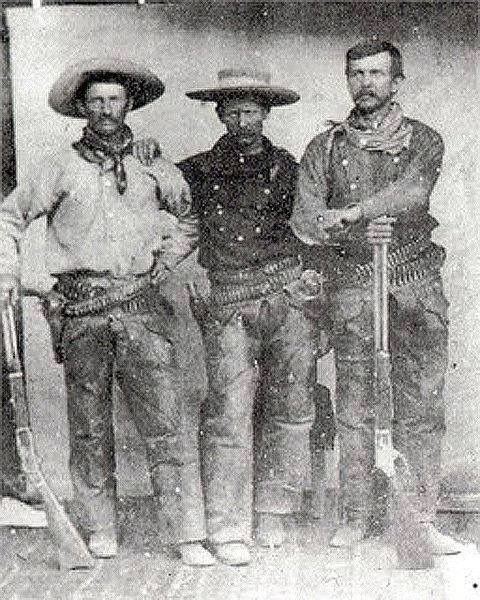

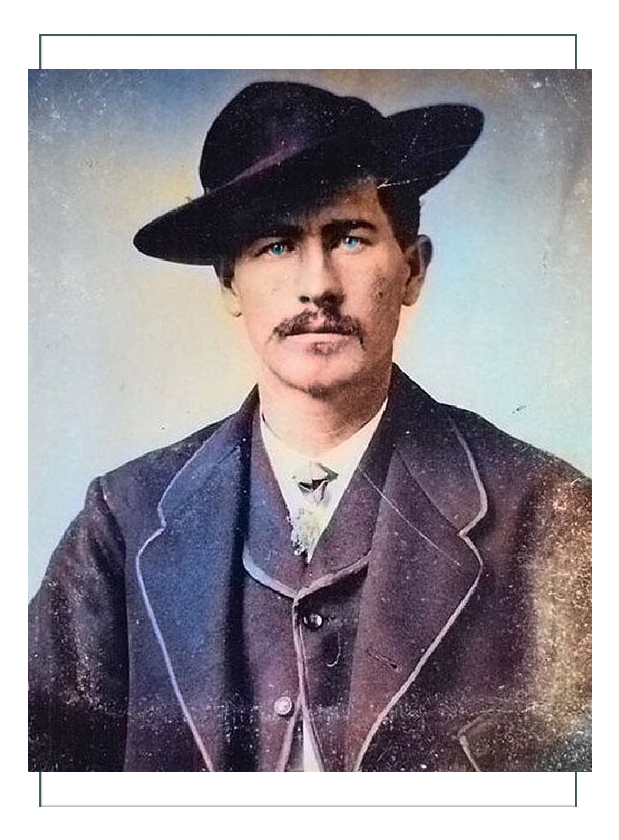

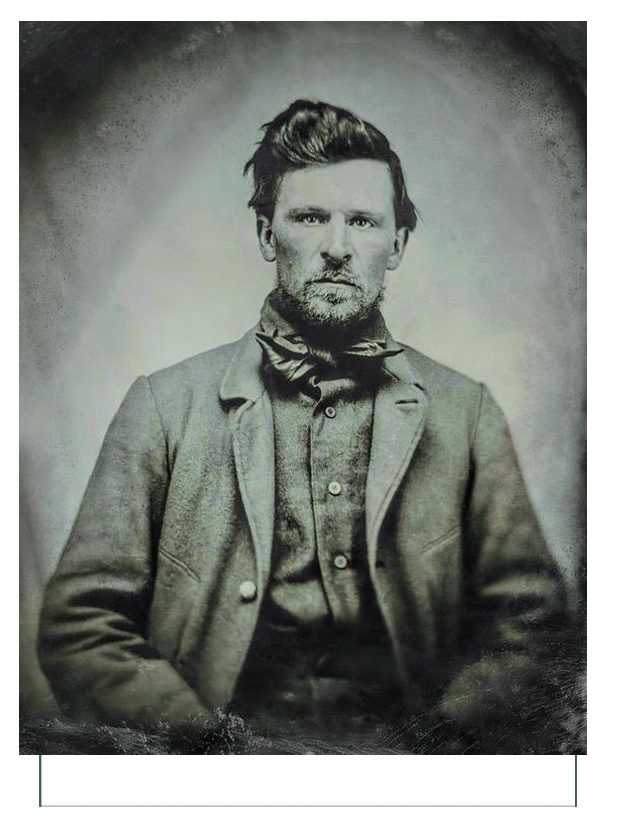

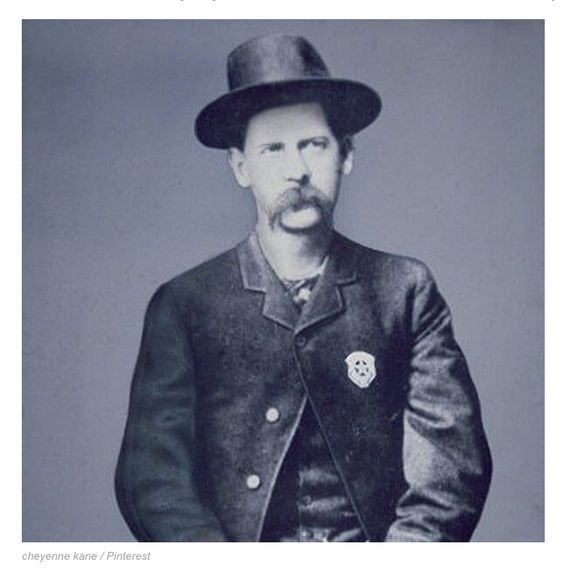

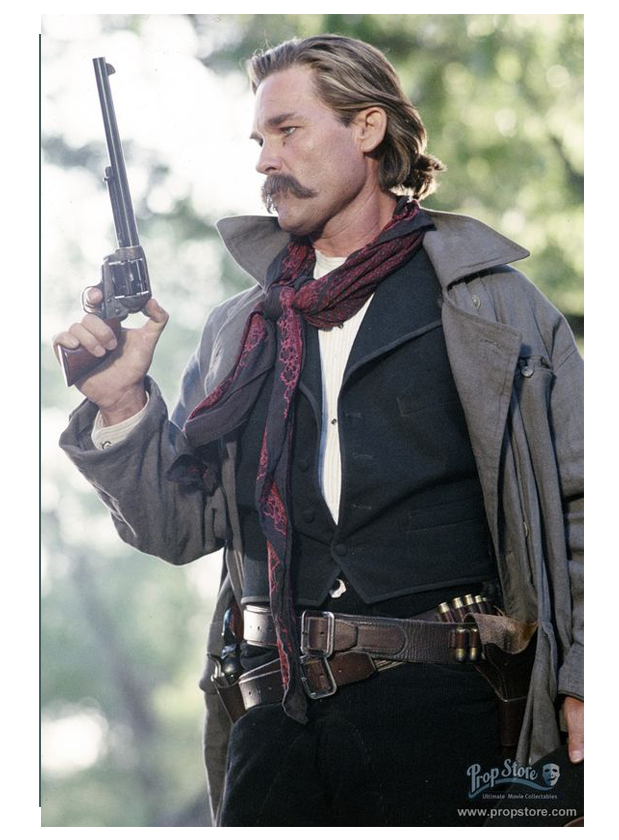

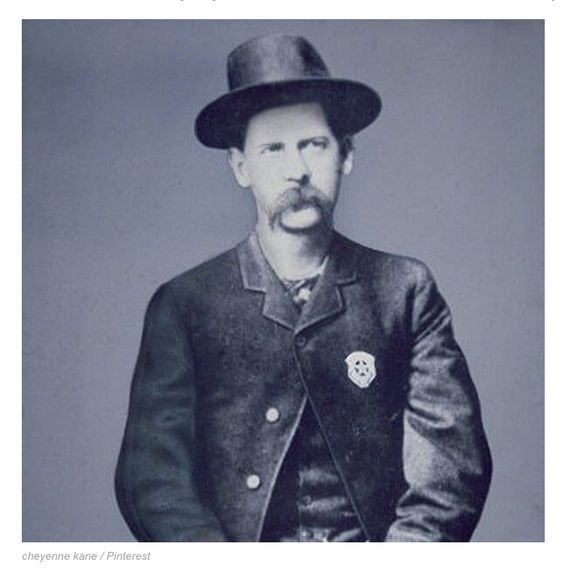

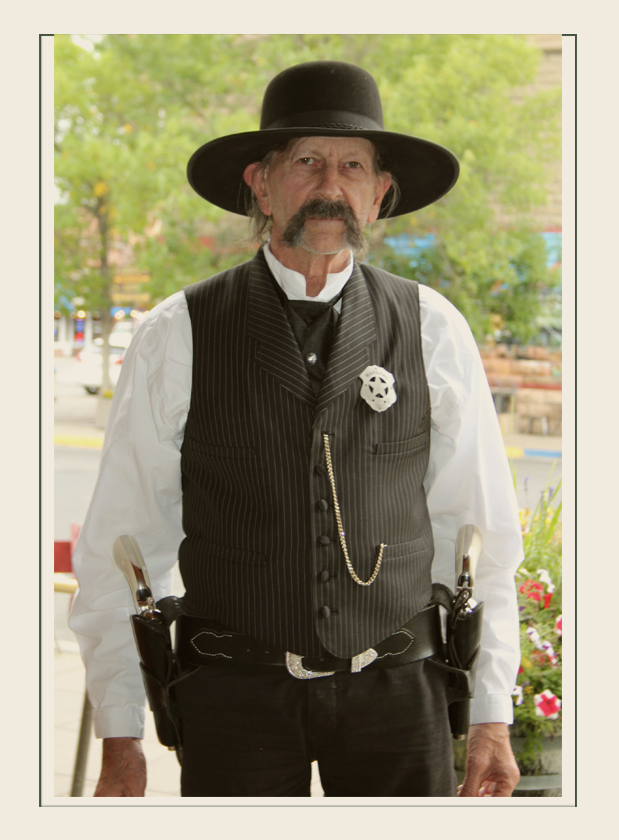

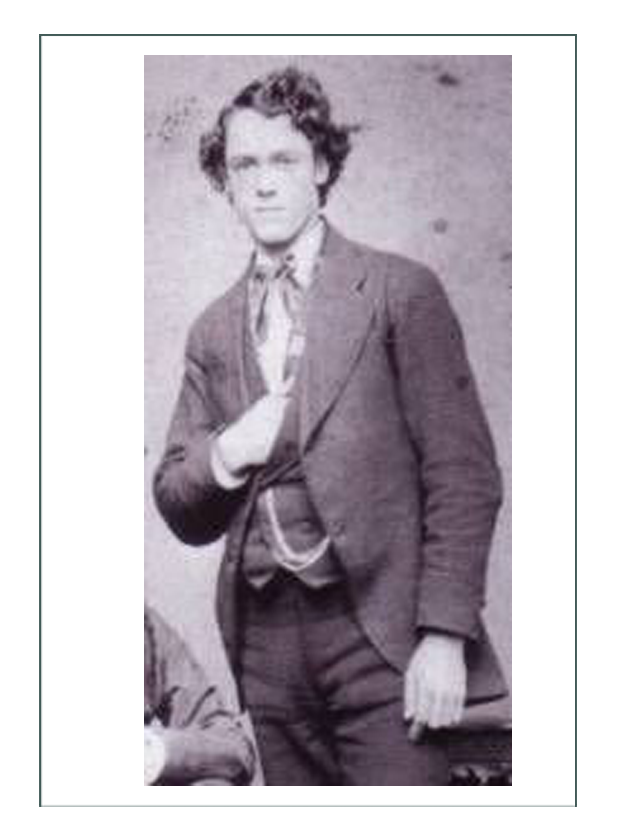

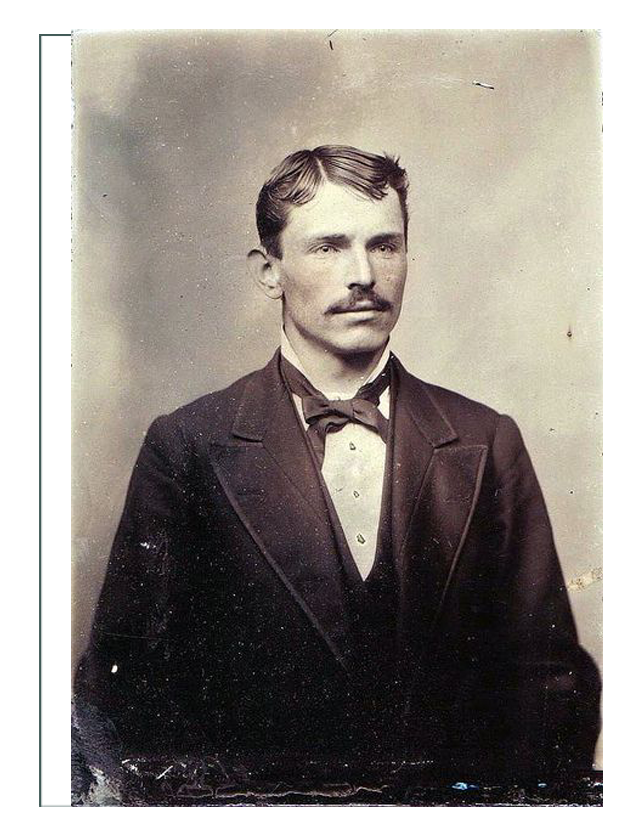

As illustrated by real photos of real Western men, they followed the high fashion of the day. Perhaps outlaws could not go into a haberdashery and buy a hat like a law abiding citizen could, but it appears they still managed to stay very close to the day and age of fashion.

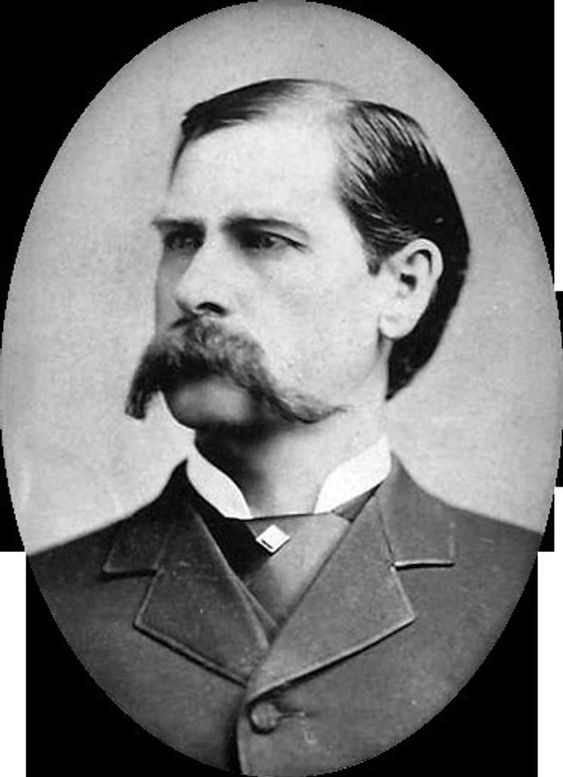

With someone like Wyatt Earp, who went from boomtown to boomtown (see Wyatt’s story on the top of the Design Development page), and seemed to have money from some source, and many times a LOT of it, he would have access to and the knowledge and the means to buy top quality, high fashion garments.

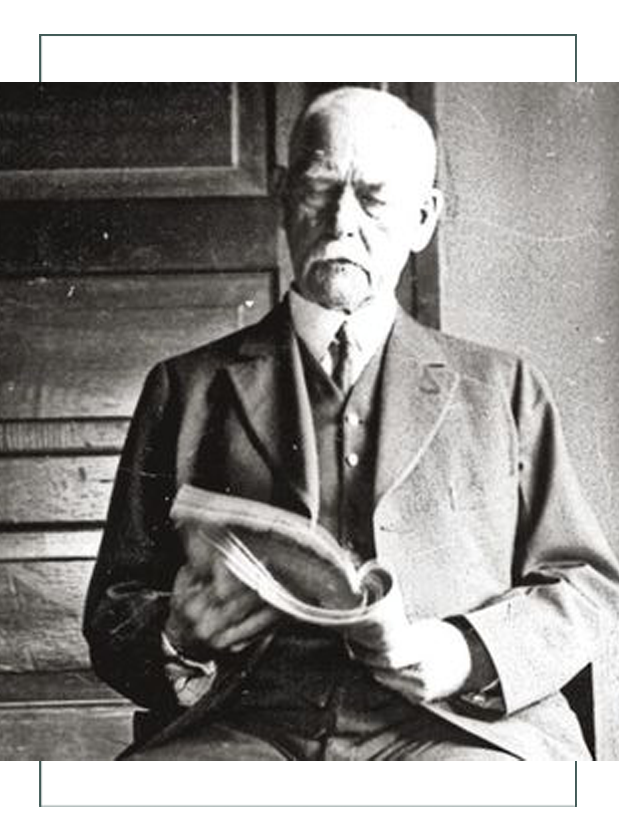

Based on photos of Wyatt, who seems to be wearing the same gray wool vest with dark gray binding in every photo from teen to old age, one can only guess what he really wore inside the saloons. Movies, books, TV shows surmise he wore silk brocade vests with gorgeous cravats and stick pins, but that would only be speculation, since what he was wearing is not described in print nor in the few photos of him.

One can only guess, given his somewhat reckless occupations, courage, and love of so many women, that he did dress in whatever was in style. He might have worn the wool and breeches of the Western rural man, and a sheared wool collar suede coat on the trail, but in town (which is this depiction) it would be silk, wool, and cashmere.

Since Wyatt lived most of his adult years in the hot southern climates (with the exception of gold mining in Alaska and other cold places), his linen, cotton, and silks would have sufficed. Perhaps he wore wool while riding, and perhaps denim. It is clear he did not favor hats., except for the functional Stetson.

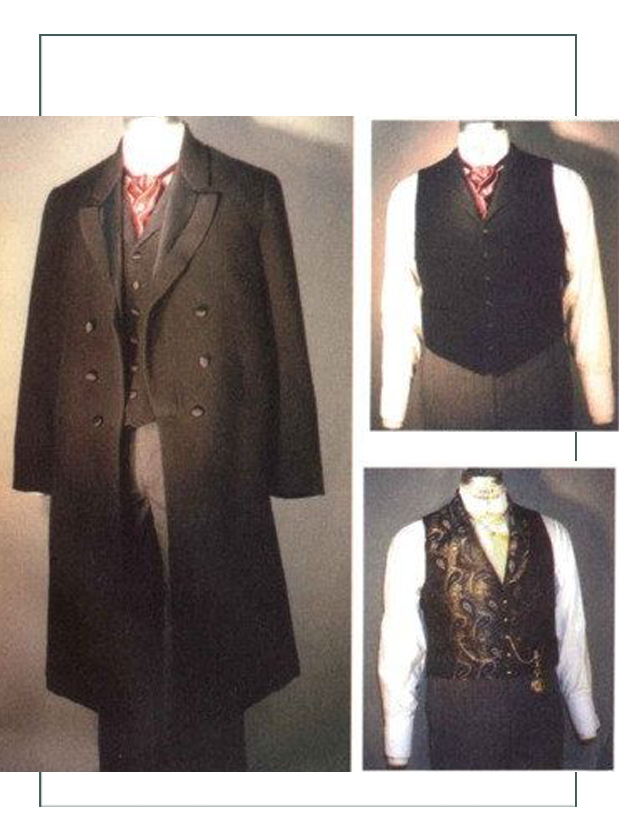

To this we defer the extensive research and depictions by our customer Andrew, that the basic black with white pinstriped vest is the correct “every day” garment for accurately portraying Wyatt Earp.

1882 Depiction

We selected the year because it fits the timeframe needed in the script for “The Wild Bunch” Cody Gunfighters, and because the 1882 vests fit the description by Andrew of his ideal vest.

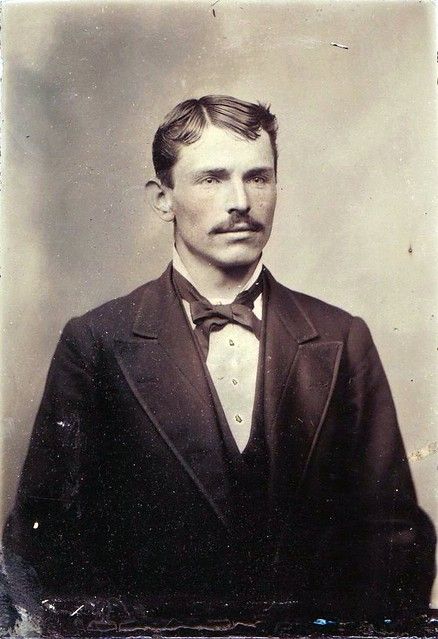

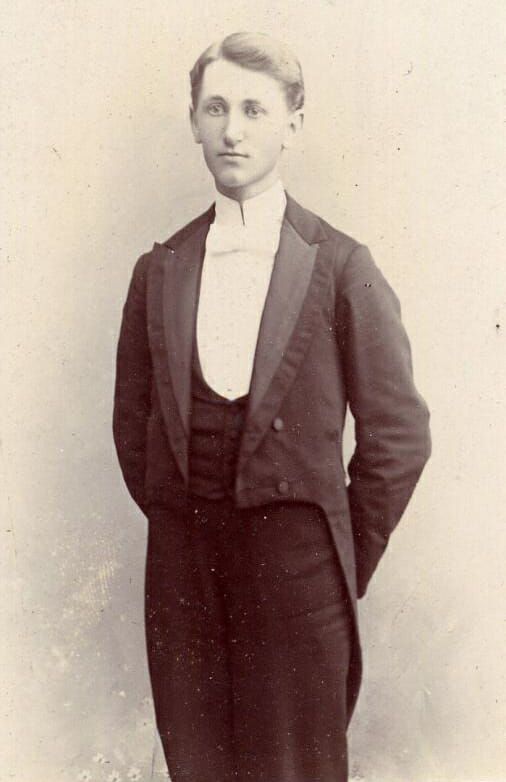

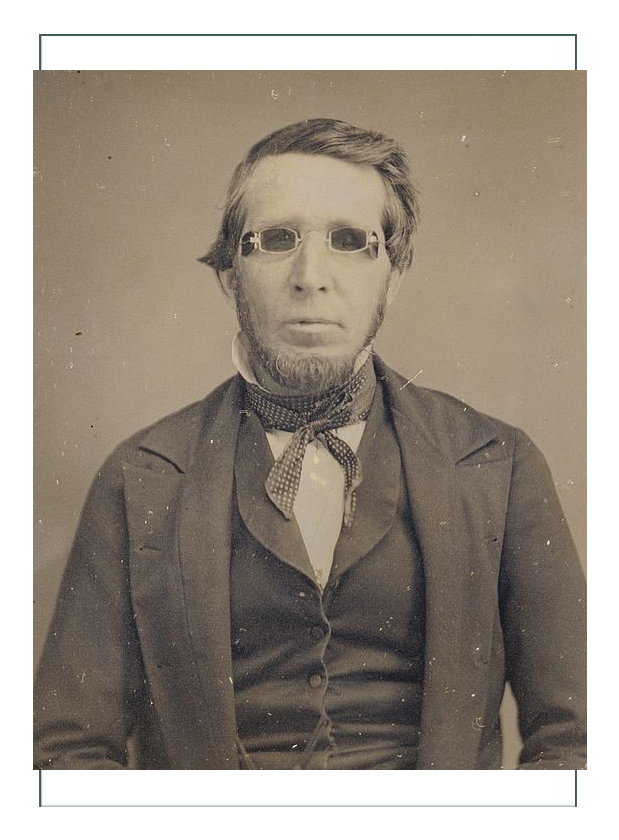

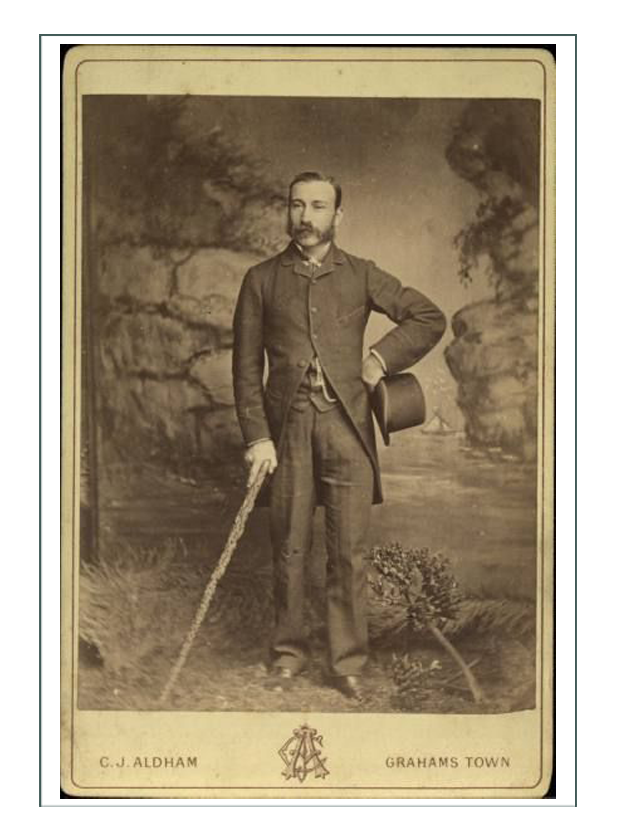

A few other photos of real people and garments from the 1880s-1882 time period that were used from which to draw inspiration:

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

(The above is a compilation of web resources)

¹Dictionary of Costume 1987 by Ruth Turner Wilcox

² The Berg Companion to Fashion 2010 by Tom Greatrex

³ https://fashionhistory.fitnyc.edu/vest-waistcoat/

4 https://vintagedancer.com/victorian/victorian-mens-fashion-history/; 1830s to the late 1890s. It is sourced from Victorian Costume and Costume Accessories by Anne Buck, published in 1961

5 July 3, 1802, Norfolk Chronicle

6 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/19th_century_in_fashion

7 https://theculturetrip.com/north-america/usa/articles/a-brief-history-of-american-western-wear/

8 Ellen Mirojnick, costume director of the stylish Showtime series The Knick

9 https://www.gq.com/gallery/the-gq-history-of-the-suit-by-decade

10 http://hespokestyle.com/mens-fashion-history-timeline/

11 https://oureverydaylife.com/mens-fashion-in-the-1890s-12485051.html

Click here to go to the Design Development Page with the Story of Wyatt Earp (next)

Click here to go to the Main Page with the Finished Project

Click here to go to the Historical Context Page with the History of Emigration