Romanticism vs. Expansionism

The fashion year 1836 sits right on that narrow line which never is really a line. As today, there were always women wearing their old corsets with the latest fashion, and women refusing to let go of old corsets. Others entirely embraced whatever was new.

At this particular time though, with fashion between the 1824-1836 being the “Romantic” fashion era, and 1837-1851 “Expansionism” era with new innovations and technologies and freedoms applied, 1836 was actually a time when women could wear pretty much whatever they wanted to from old or new, and had many options in how to wear it.

This time would more aptly be called the “Early Victorian Fashion Era”. 1836 would mark the start of it even though Victoria’s influence actually started half a year later. Again, January 1st does not exactly define the start of an era and end of another.

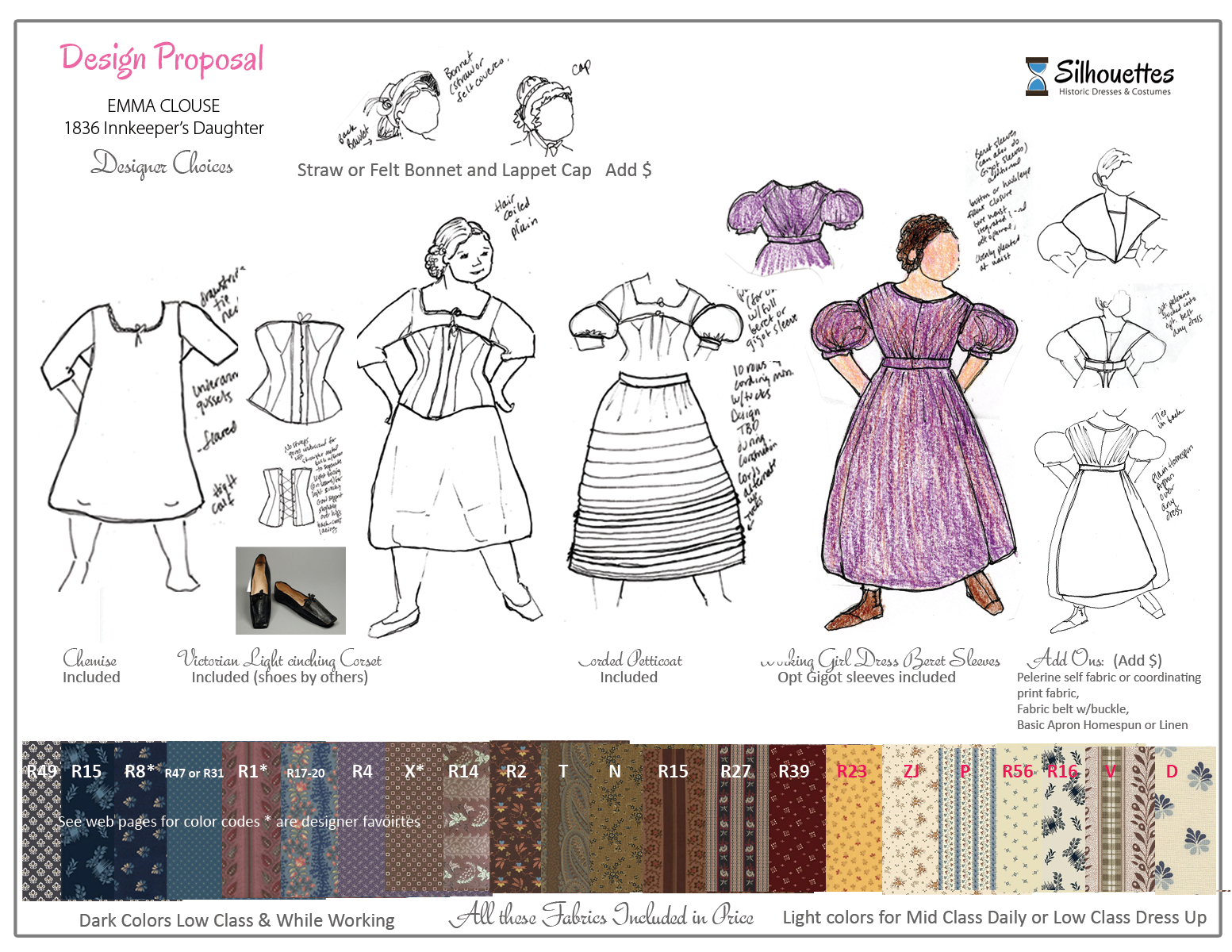

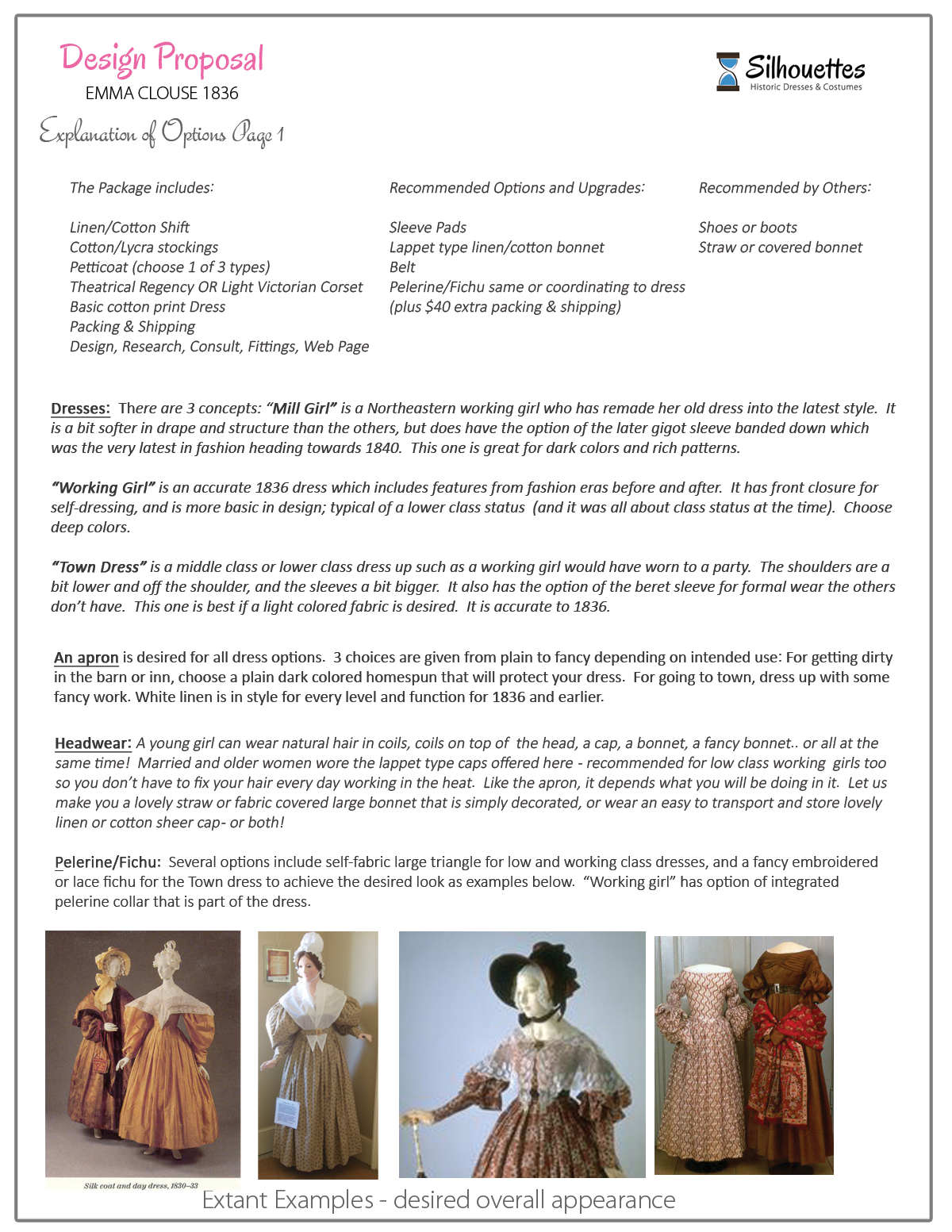

Because there are so many options and choices for that year, to determine the best design and construction for Emma’s ensemble, we need to look at what the two eras have in common that we can draw inspiration from. We need to look at real garments to see how the fashion principles were applied in reality, and then to see what we can find right now and in her budget to best duplicate or represent the era.

What is “right” however, will be what the anthropologists think is right for their living history town, based on the characters Emma has chosen.

Key Concepts

From our heads we know these things:

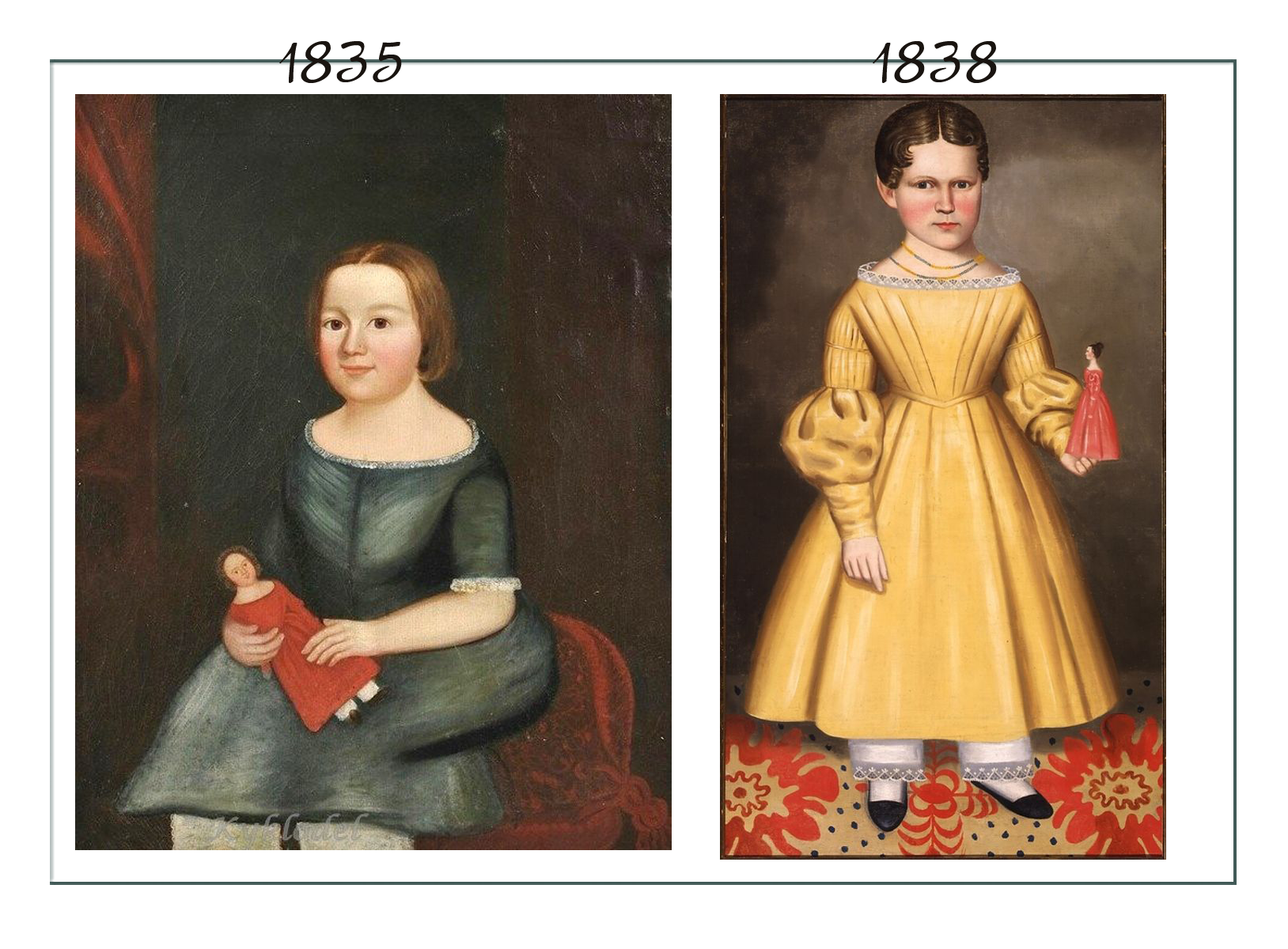

- almost everything was still being hand sewn, and that still being mostly by men, although traveling seamstresses would stay in places, or had shops in a town and people would “send out” for their garments;

- clothing was expensive, and therefore was valuable, and people treated it well, although they worked and reworked it until most likely every day clothing from this timeframe just disappeared as washrags or in rag rugs;

- what women wore was still the basic uniform the same as it had been for centuries: a chemise type top, some sort of corset or stays, and a robe (dress – 1 or 2 pieces) with draped accents like scarves, and variables of sleeves or not sleeves. The big difference was from all women of history that they wore or didn’t wear drawers;

- information and design innovation was still at this time generated out of France and French fashion houses, although the application of that fashion came from Queen Victoria of England, who gathered inspiration from all over the world and from English holdings in particular which were vast and wide;

- American innovation in particular was starting to shape what women wore because function had long been a priority for American women regardless of status or occupation. The development of the American West brought completely new concepts IN to the worldwide pool of information for the first time in history. (except in the 1770’s when Ben Franklin showed the world his natural hair instead of a wig);

- Innovations such as the use of metal lacing grommets and busks as well as new dyes, fabrics, and techniques influenced the design particularly of undergarments and skirts at this time

Comparing Eras

The changes in fashion from the 1820’s to the 1850’s was largely politically motivated, and reflected the advancements of technology. They also reflected the changing attitudes and place of women in society.

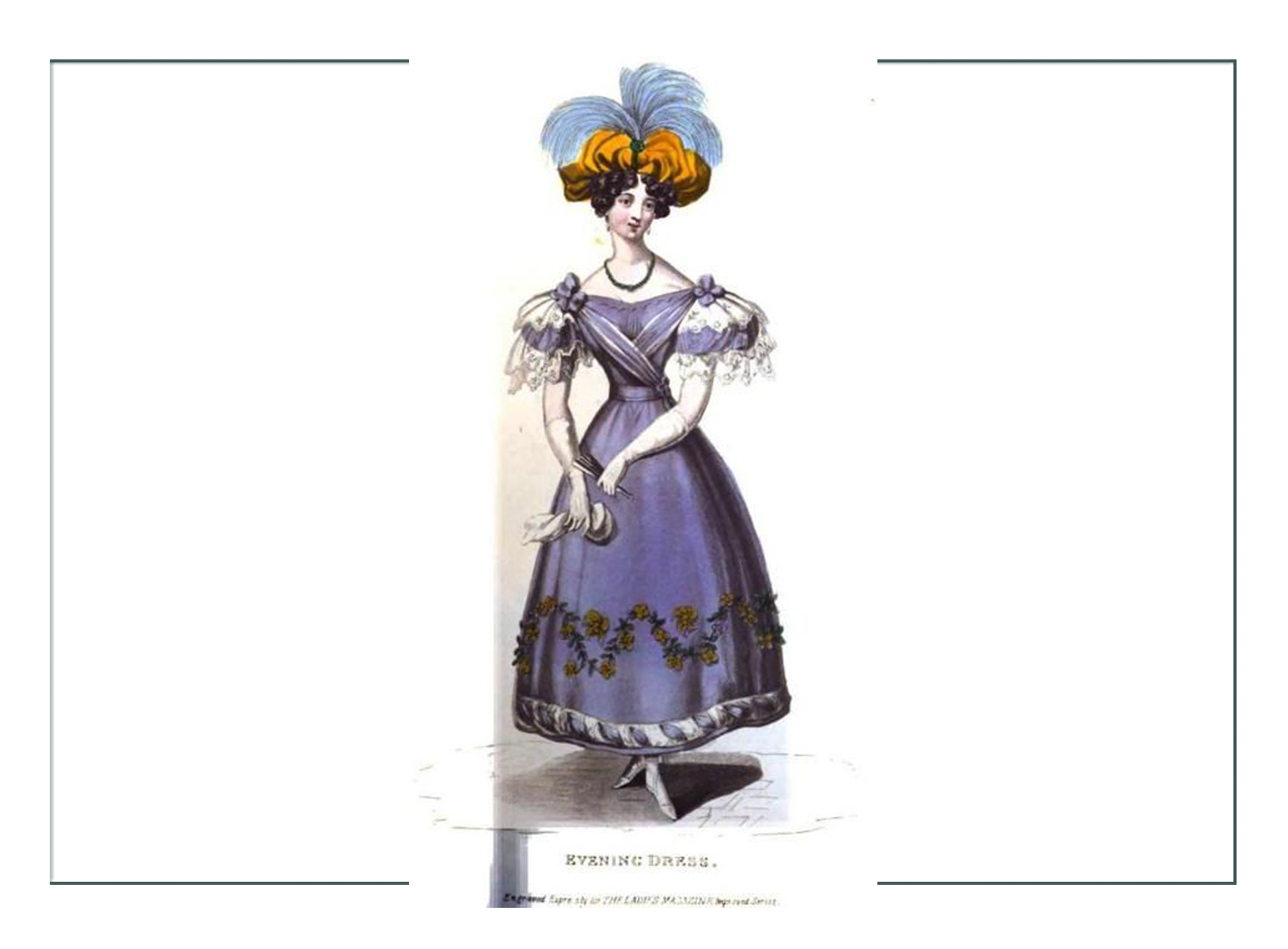

In the Romantic Era (1825-1836) inspiration for fashion came from Europe, and from literature. It might have been called the age of “innocence and artiface”, because romantic fashion was extremely well thought out and planned to create specific moods and illusions. It was also very expensive.

By the Expansion Era, things around the world were moving much faster, and America’s west had begun to influence fashion. With Queen Victoria firmly at the head of the creation of worldwide fashion, the “costume” became something entirely different because a woman was required to dress for the activity. This was almost the “inverse” of the goal of Romantic fashion was to create a mood. In the Early Victorian era, the situation was creating the fashion. Early Victorian fashion was also very expensive.

One of the primary influencers of both eras was the fast developing technology of the sewing machine and mass production. There had been sewing machines and mass production for quite some time, but both Romantics and Victorian women somewhat shunned them. They felt readymade was vulgar and for the lower classes because they related “mass production” to “uniformity”, and they wanted to remain individuals.

Men, who had been wearing uniforms for some time were actually the first to enjoy mass production, while women continued to hire dressmakers who traveled from town to town. Some bought from the new department stores, but those were still customized.

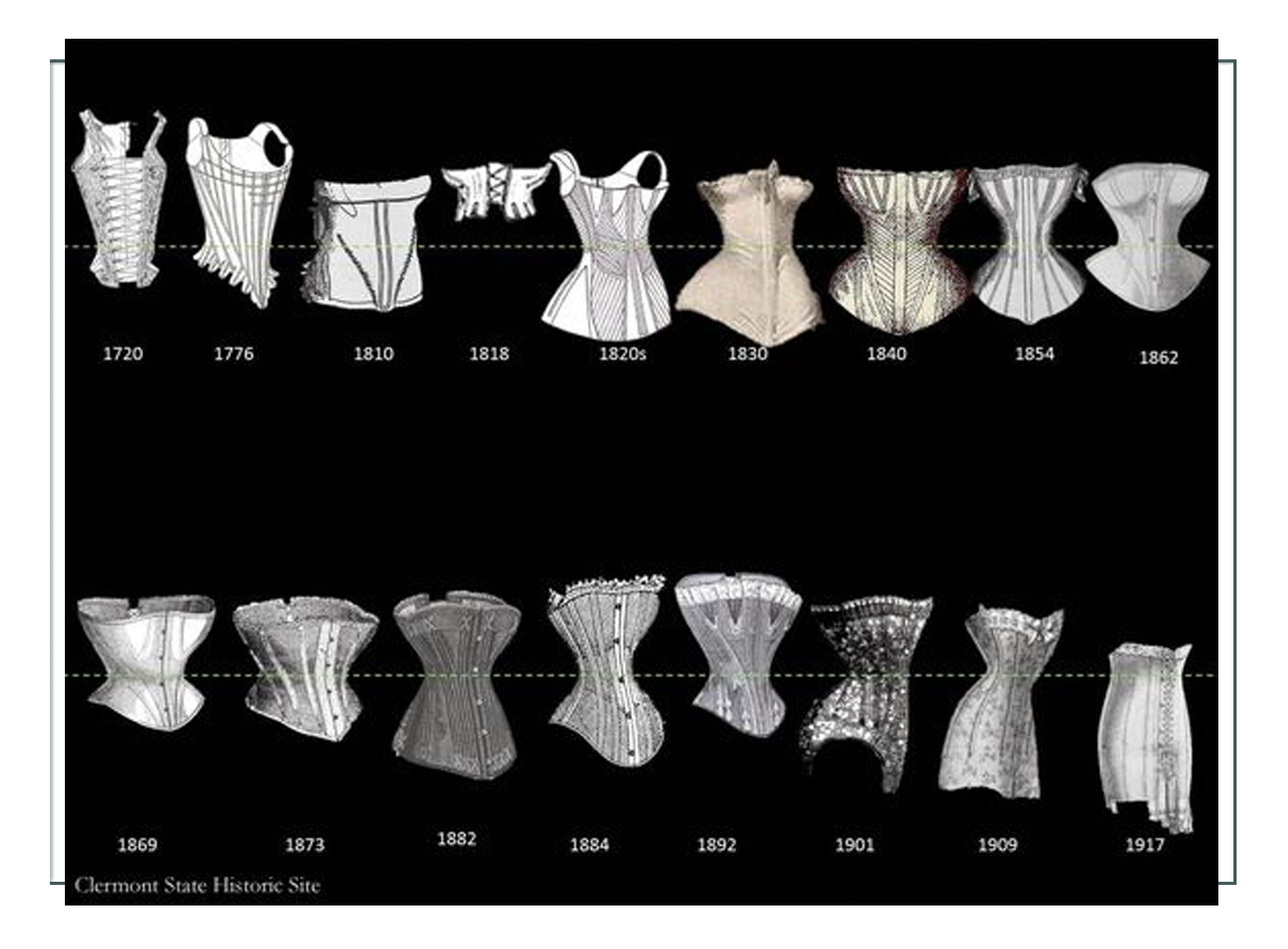

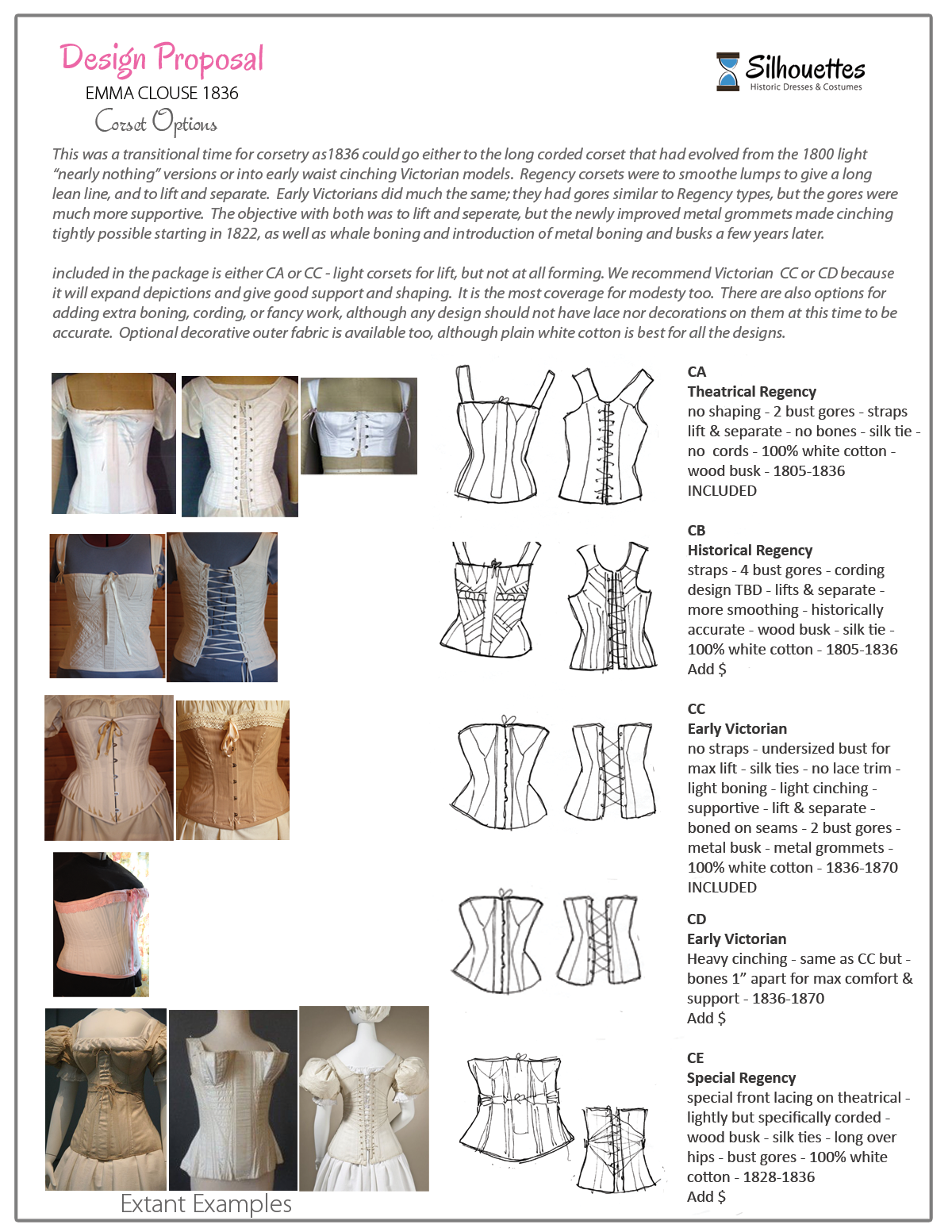

This attitude prevailed with corsetry too. Through these decades grommets and bones and lacing continued to become stronger, and the new couteil (dense herringbone woven cotton) fabric was developed in America specifically for corsets. The Romantic 1830’s gored and gusseted corset that lifted and separated the breasts into round orbs, evolved by the 1850s into a non-gored corset where the pieces were shaped. The 1830’s corset which had evolved from the Regency transitional corset which was first designed to smooth out lumps and to lift the breasts, still had the “lift and separate” concept with strong center front busk. It also went over the hips a bit to smooth, though that was done with gussets so they were not shaping; they were smoothing.

By the 1840’s, the corset was stronger, tighter cinching, and shorter. It did not have the bust gores so the breasts sat in a more natural position and shape, although emphasis on width was obtained by the shape of the seaming which enhanced the shape of the bodice of the day. That shape would stay much the same going shorter or longer and changing the types of seaming until the late 1870’s when corsets would go long.

What is important to note is that American corset companies were leading these innovations, and along with the introduction of western women’s apparel which in many ways imitated that of men in comfort and practicality, American women started to influence world fashion, even though Victoria remained in charge.

What is seen then in 1836 in American rural women is some practicality and comfort introduced differently than High Fashion in the rest of the world. This meant American women wore garments with less ornament and more durable and practical fabrics than their high fashion counterparts. They still wore high fashion of the day though.

Feminine vs Bostonian

It is important to note that while the politics and innovations caused changes between the two eras, the overall world situation and culture in America had great influence on fashion. The focus of the Romantic woman’s life was to be feminine – to appear feminine and to act feminine. “Feminine” could be defined at the time as meaning “creating the calm in her men so that the world would become a better place.”

By the Expansion era, with women working alongside their men charting new territory and breaking new barriers in society such as gaining rights over their children and the ability to own property that would come in the next decades, a woman was defined more by what she was doing.

Unlike Europe, Americans did not have a strong class of elites. The young country did not have a social system defined by ancient nobles or societal dictums. It was a bit “raw” and “fresh”, and the strength of America at the time was a strong middle class. That meant that any person could rise (or fall!) by their own efforts, to whom was in the middle was constantly changing – but there was always someone in the middle.

The “Bostonian” woman was an idealized figure of a woman who had the means to travel, to “do the continent” and to behave such as the nobles and elites of Europe – but to do so by gaining her own wealth and finding her own way. While it was the rare few who could do that, the new ideal for women to strive fore meant their goals had to include figuring things out and finding their way – apart from their man.

They still had to have “their man” (society and women’s rights and laws had not come that far yet) to survive, and marriage was the objective of most women throughout both eras, but there was a “niggling” sort of thought planting in the back of the mind of the Early Victorian American woman that she just might be able to do it on her own.

Fashion Specifics

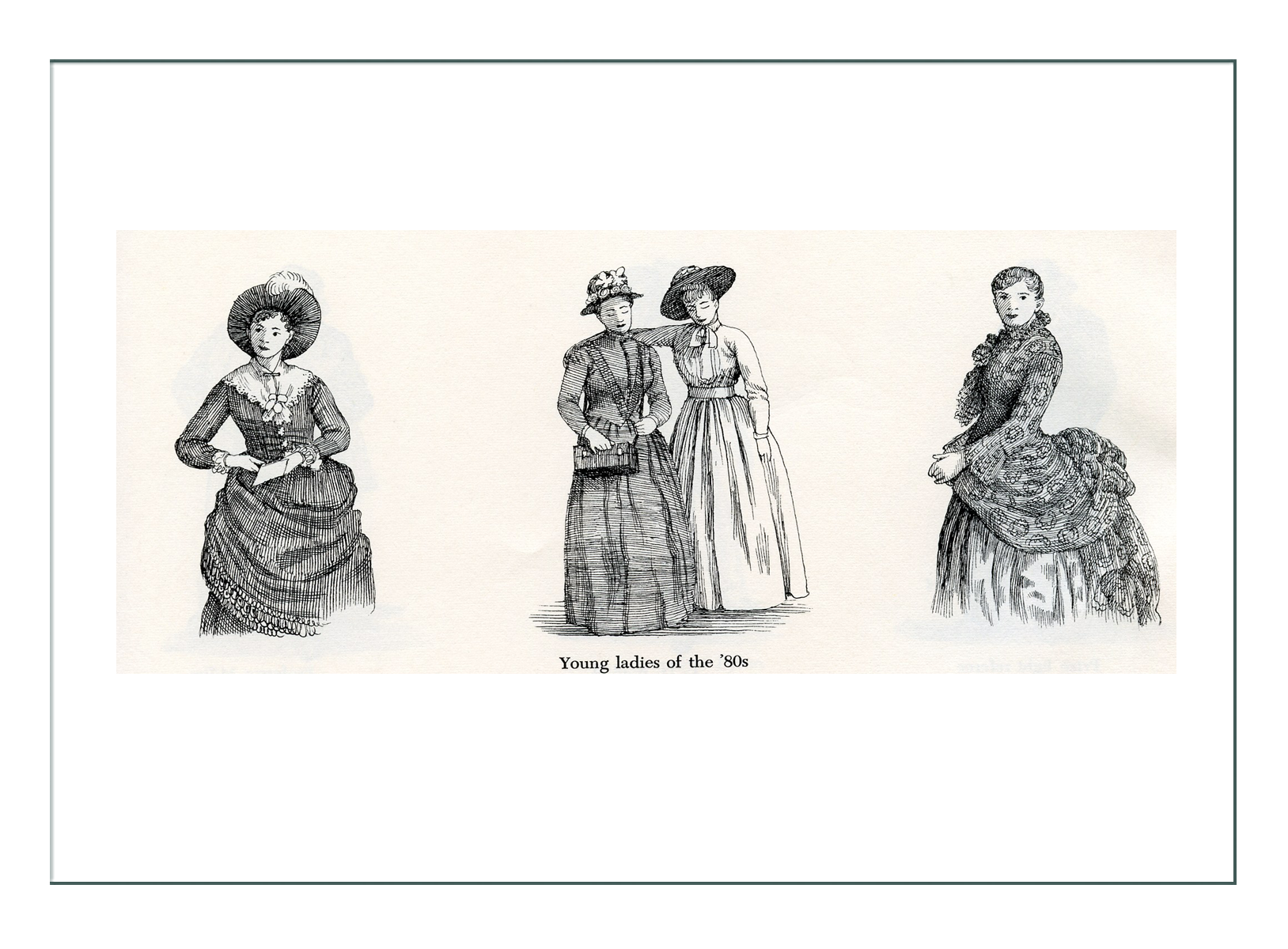

The changing attitudes and resultant behaviors between the 1820’s and 1840’s for American women merged in 1836 to blend similar, yet constantly evolving fashion styles. Much of the changes had to do with function. The Romantics couldn’t do much work wearing those giant sleeves and open bodices, so with expansion of women’s roles, their garments expanded in some ways, and deflated in others.

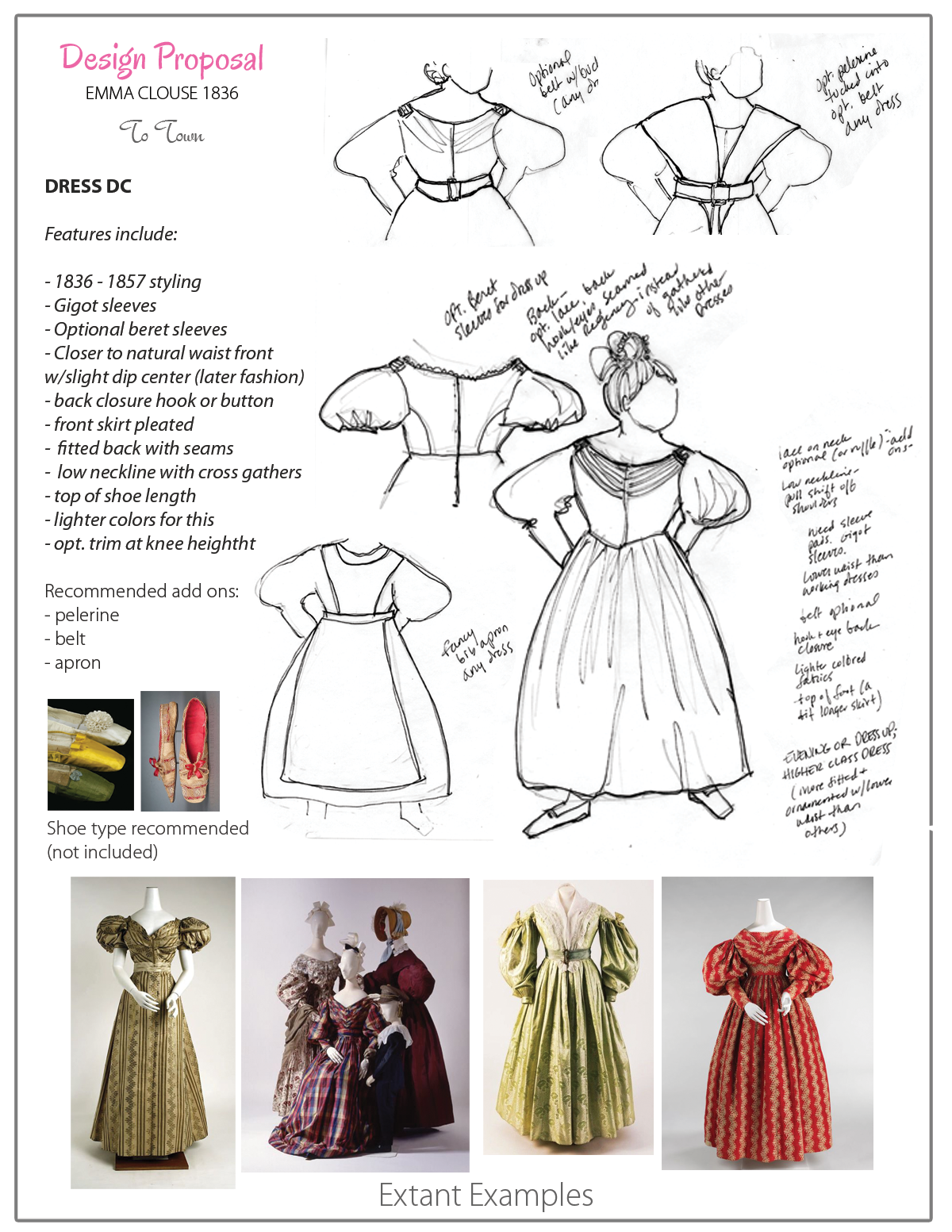

Bodice & Collars: The 1824-30 emphasis on shoulder WIDTH by use of the wide collars, and straight belt with straight waistline slightly above normal, yielded to the 1835-1851 more fitted neckline with narrower waist at the natural line. The new bodice had a slightly pointed center front, and the new belt had top and bottom points. As time went on, emphasis on wide shoulders became emphasis on a curvy bust AND wide rear end. Further significance was the one piece “dress” became the two piece “bodice and skirt” that would continue as the main garments until about the 1920’s.

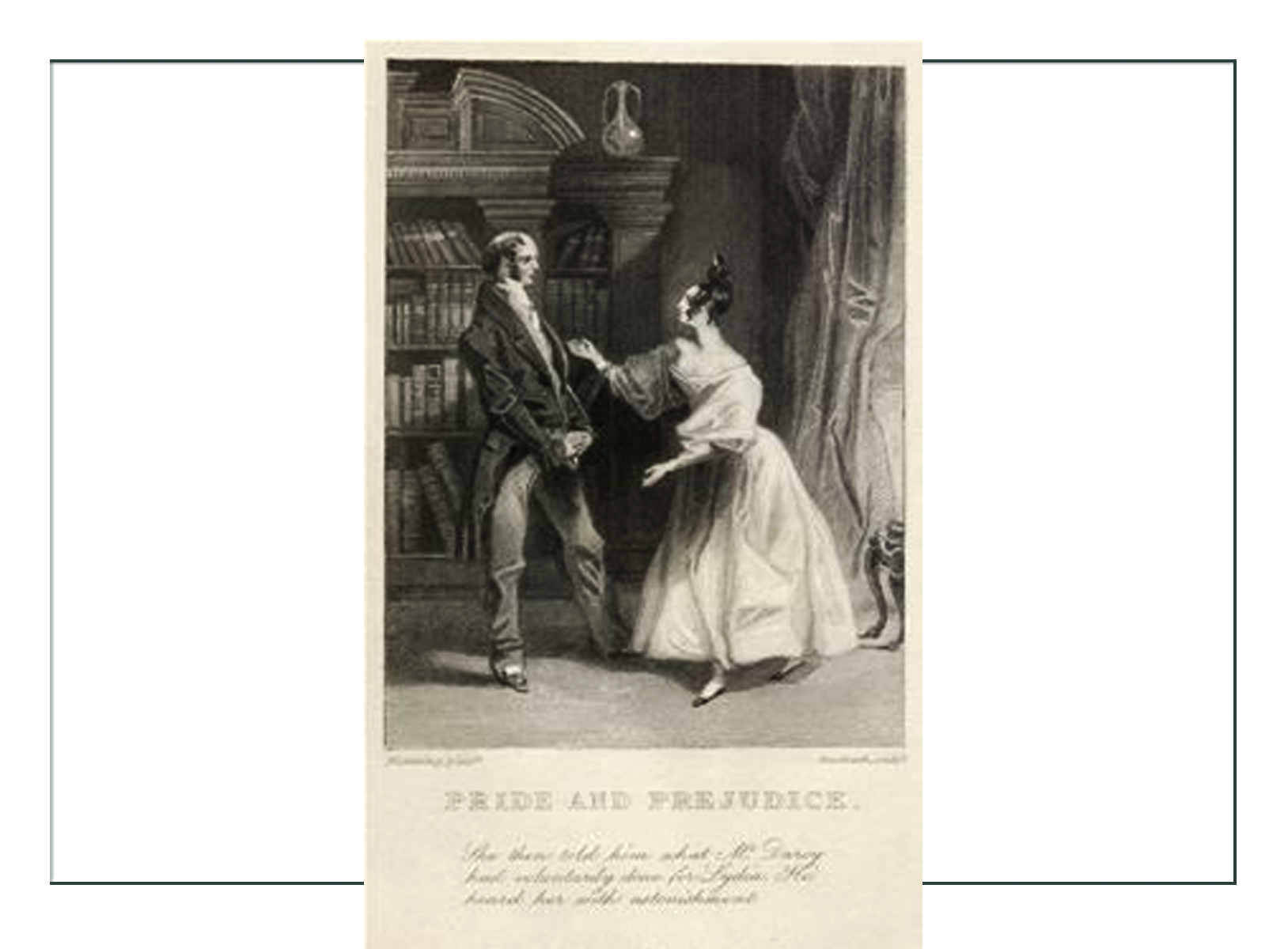

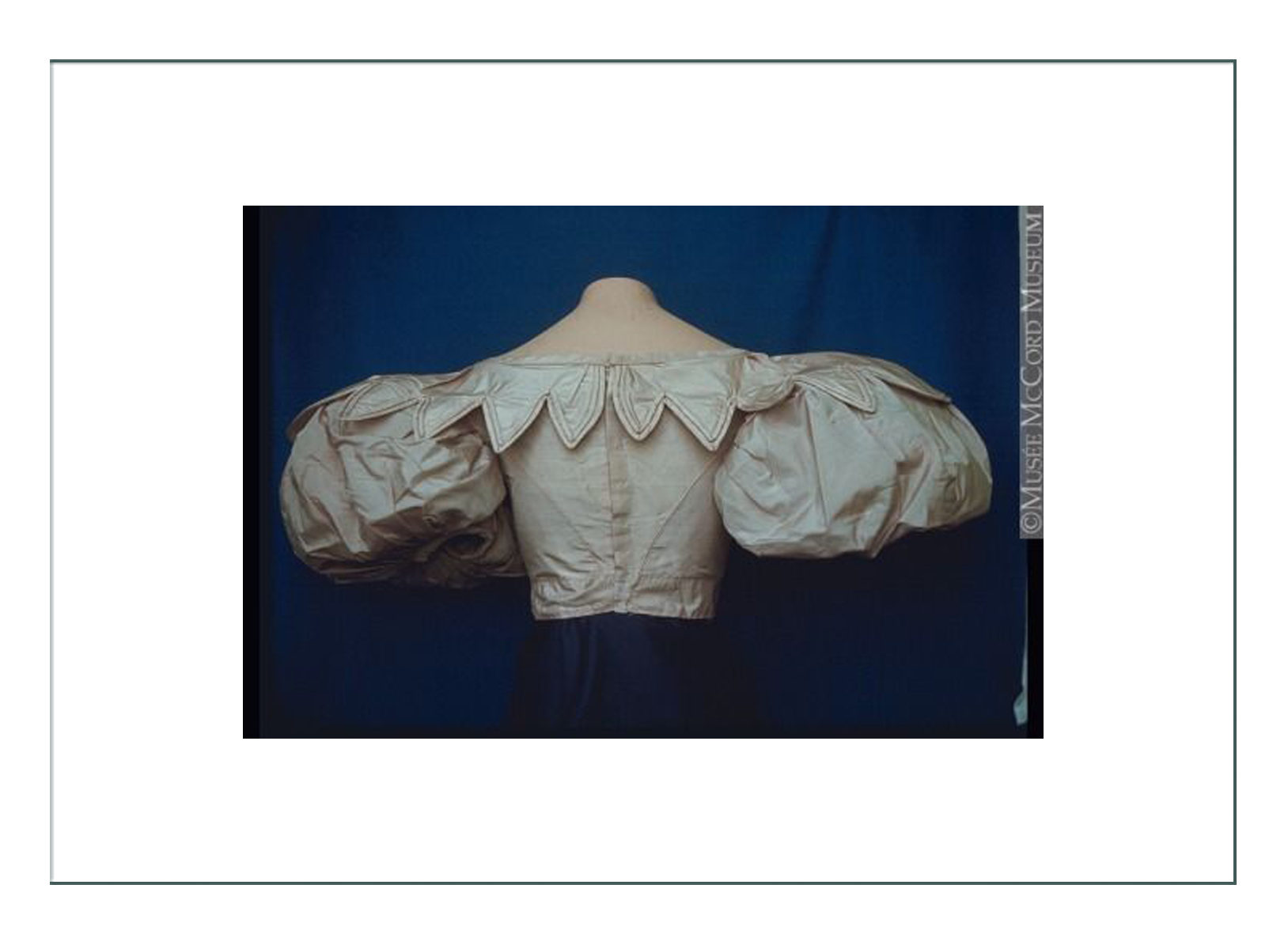

Sleeves: Most notable to distinguish the eras and the year are the sleeves. In the late 1820’s, a “tippet” collar sat on top of a huge “gigot” sleeve. Summer dresses had long sleeves, while evening had only the top puff. These “gigots’ were full below the shoulder from shoulder to elbow, and then fitted from elbow to wrist. The lower section was cut on the bias so a woman could move her arms. (Later 1860’s sleeves would have to have tucks and pleats so a woman could bend).

These would disappear suddenly in 1837, presumeably under the fashion lead of Queen Victoria and her designers. The “gigot” would completely disappear, leaving a straight sleeve, and would reappear in 1891-3 as “Elephant” which were of different construction and positioned higher on the arm and inset into the shoulder seam rather than positioned below the collar like in the 1830’s, and the “Leg O’ Mutton which was a very full entire pouf over a straight forearm). the 1830’s sleeve sloped away from the shoulder and down the arm; the shape being created by inserts at the head of the sleeve and very complex pleating. The “gigots’ began in 1830, and were the largest in 1836.

There was also a “beret” or “puffed” sleeve which was actually more similar to the 1890’s sleeves. It was cut from a full circle with a slot or circle cut out in the center to put the arm through. The size and shape of these varied greatly depending on how the circles were cut. Sometimes a “puff” was placed inside a sheer “gigot” for what we would consider the effect of having a Mickey Mouse balloon inside a big clear round balloon at the County Fair.

Skirt: From the straight Regency gowns (robes) to the 1820’s and 1830’s “bell shaped” skirt, by 1835 the skirt was now pleated all around and full and symmetrical. The earlier versions had pleating that started in center front and radiated to the sides, but as time went on, the skirt grew closer and closer to a dome shape. The length by 1836 was across the top of the foot, whereas it had been at the ankle in the 1820’s. The skirt would continue to become longer for many years to come.

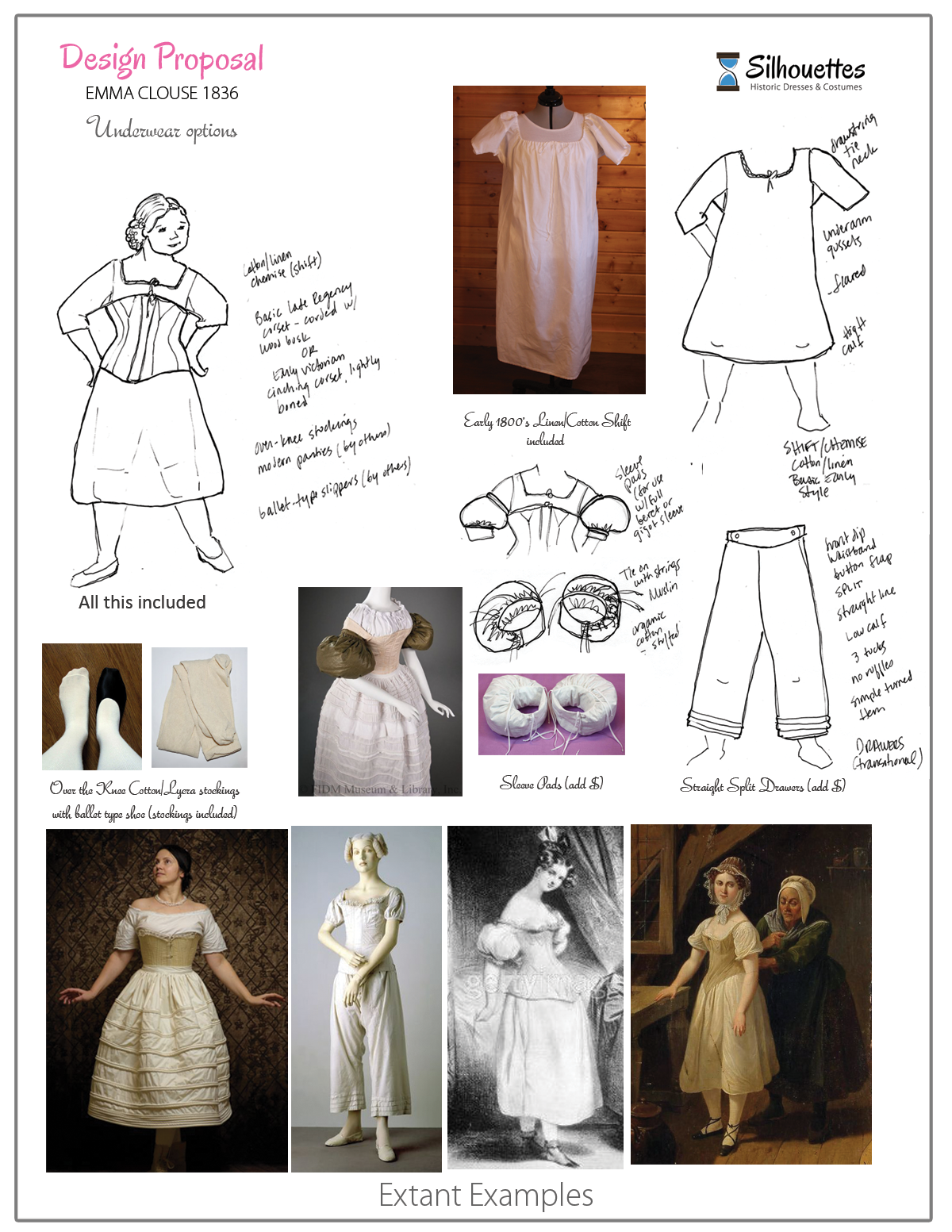

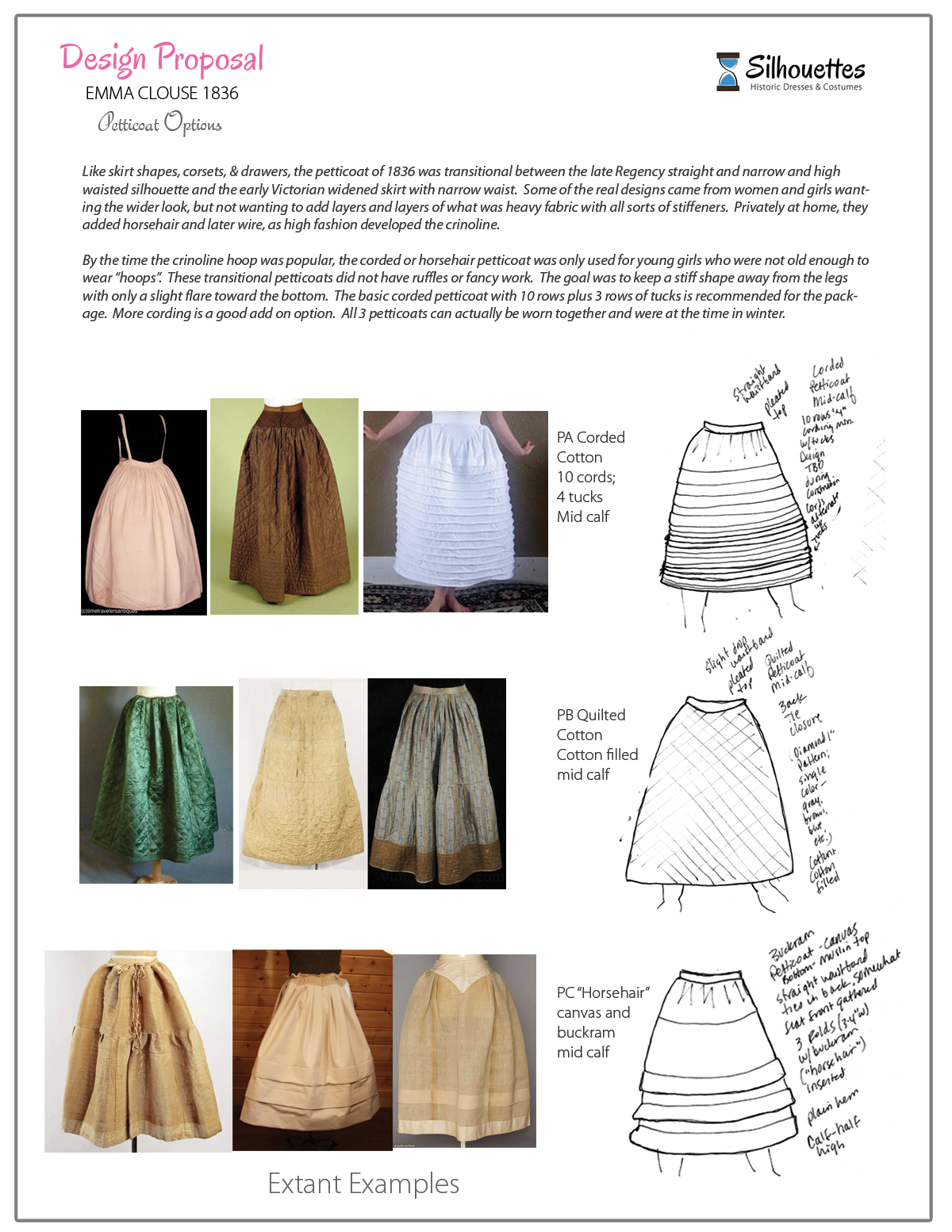

Petticoats: Evolution of the petticoat was largely responsible for the changing skirt shape. The Regency era from which the fashion was emerging had women wear little to nothing underneath their dresses. They then added simple petticoats for modesty that hung immediately under the breasts (“empire waistline”), and as the waistlines dropped towards normal, so did the petticoats until they rested around the waist. Because the skirts in the 1820’s were still relatively straight, simple and straight petticoats with some stiffening were all that was needed. As time when on, those needed to have horsehair and buckram or cording and pleating to stiffen more than starch could. As the decade progressed, they added layers of petticoats stiffened and starched in various ways, until the introduction of the crinoline hoop in 1855 which stripped away all but one light petticoat to cover the splines of the hoop.

Petticoats then in 1836 would have been very heavy, stiff, full of stiffener, and would be worn in multiple layers.

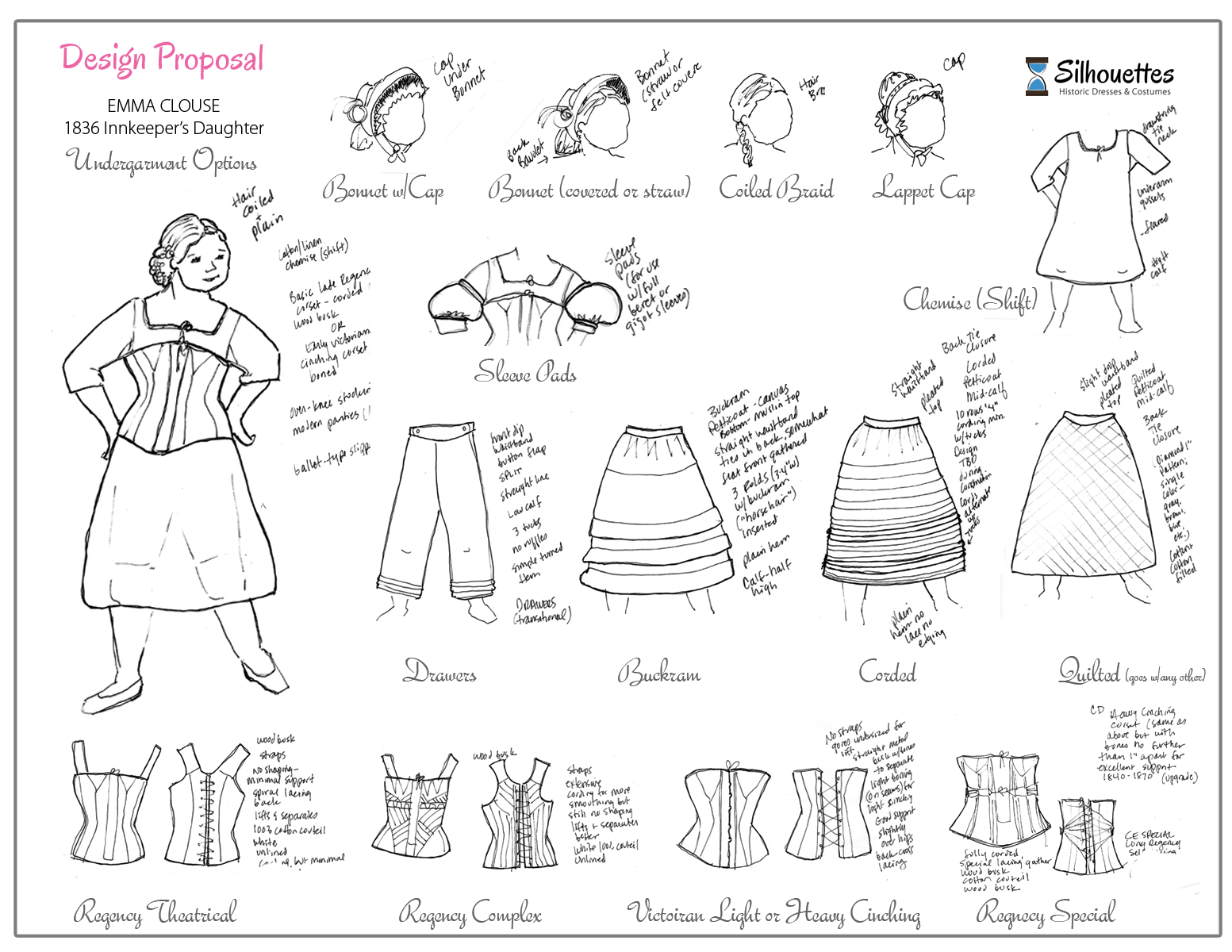

Undergarments: There is some discussion regarding when drawers (later called pantaloons, pantalets, knickers, but at this time drawers was the appropriate term in America. Bloomers were always a specific garment and not an undergarment invented in 1855 and only worn in insane asylums until the 1895 bicycle craze demanded a split sports garment) were worn in the 1830’s or not.

Extant (museum) examples show a very plain and simple, unadorned type of split drawer was worn with a tightly fitted leg and fitted waist. This was worn under the corset. Other references indicate only a multitude of petticoats was worn underneath, similar to what was worn in the prior century. There are some very interesting examples of what look like fishing boots that tie under the bust and not around the waist from this era. We can only assume it was a time of experimentation and testing until Queen Victoria took over the reign (reins).

The chemise was now called a chemise after the French versions. In the 1830’s, this was almost identical to the linen shifts of the 1790-1805 period, or perhaps a combination of the early and late Colonial shifts. Features included lightweight linen hand construction, knee length, wide body not shaped with slight gores, drawstring neckline, 3/4 sleeves, no ruffles nor lace; no ornament. Plain.

Corsets: As discussed above, by the late 1830’s the new American cotton couteil fabric and all metal parts had replaced the soft corded and unstructured Regency styles, although some of those were still worn. The new cinching corset was coming into style. Early in the 1830’s it still had bust gores with the objective to life and separate. As the decade progressed, the gores were replaced with seaming, and there was not so much lift, but there was more cinching. At this time there was not extensive padding, and with the increased mass production of corsets, it came to be that instead of custom corsets to fit the woman, women bought corsets and then were shaped into them. This began the next 75 years of molding the female body.

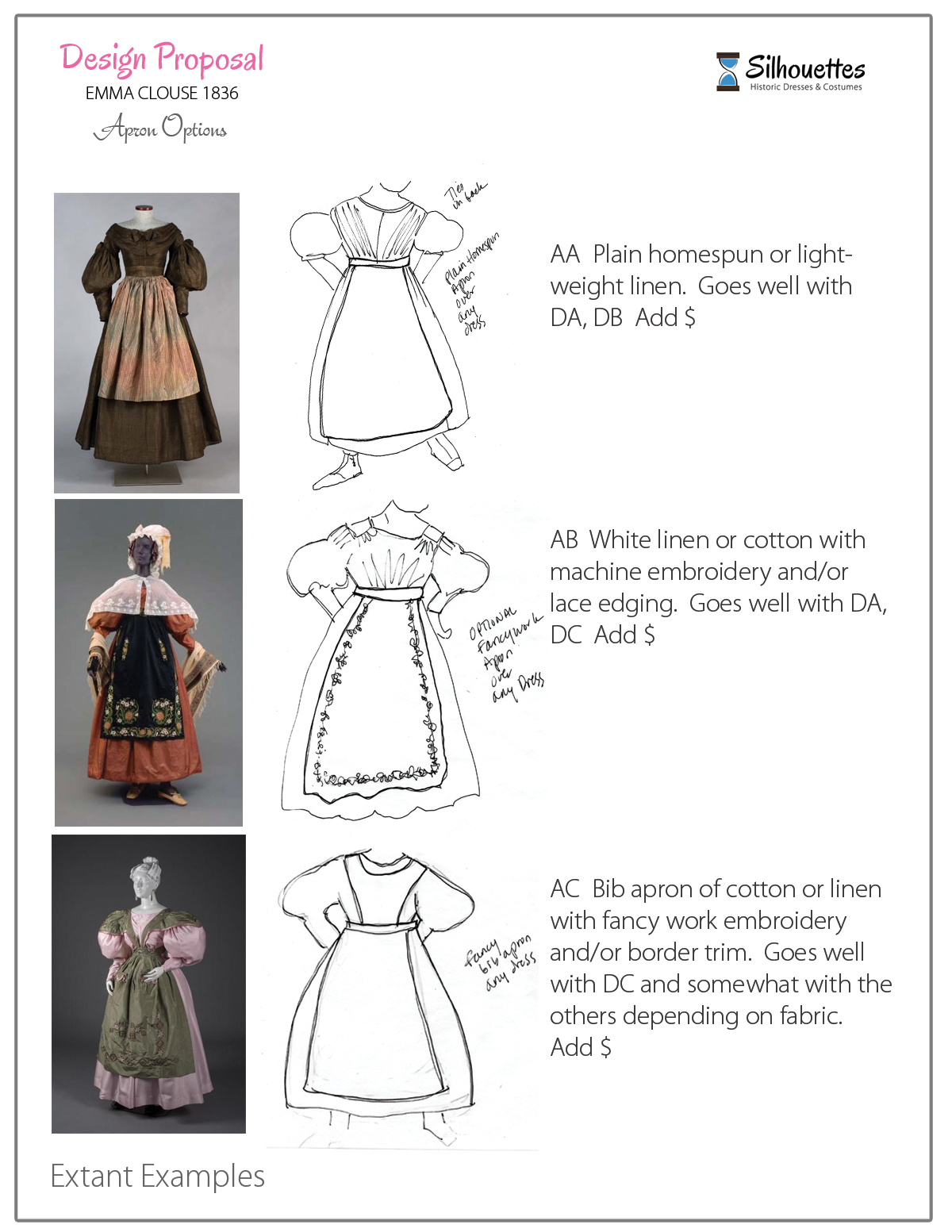

Fabrics and colors: We discuss these in detail below in general and specific to 1836, but generally the Romantic Era began with their obsession with the deep velvets, brocades, and rich fabrics typical of the Renaissance which they idealized, and as time went on, they lightened up to include more cottons and embroidered cottons and fabrics that were “lighter” visually.

About the mid-1830’s, the light embroidery became rich in color, dense, and heavy. They had heavy motifs, and larger, deeply colored floral embroidery. As 1840 approached, that would switch to woven embroidery such as the cotton “broiderie lace edging” and woven white -on-white stripes. Towards 1840 decorations were at the knee height on the skirt.

Colored stripes and dots became favorites by 1840, and cotton prints were common and reasonably priced for most women. Favorite fabrics in America of choice was cotton chintz (like 18th century high class status women wore imported from India), challis (silk and wool blend), cashmere, and merino and other special wools and hairs. Linen lost its prominence as the other fabrics became more accessible.

Note though they were all still natural fabrics and natural dyes at this time, and while mass produced items might be sewn on an industrial sewing machine, most garments were still sewn by hand.

We note the anthropologist (see bottom of Emma’s “Fashion History” page) indicates fabric type, color, print, pattern, and application in the overall design is of the most importance. She writes:

“There were a great variety of fabrics available for making clothes in the 1830s. They were all “natural” fabrics; wool and linen were most common, with cotton and silk were scarcer and more expensive. Hundreds of weaves and patterns were available.

A rich selection of colors existed even before synthetic dyes were developed in the late 1850s. These early colors were made from plant parts-leaves, stems and blossoms of woods and meadow flowers; roots, barks, nut hulls and tree galls; berries, fruits, pits and skins; mosses, lichens, and fungi and non-plants, such as insects and shellfish.

Many dye sources were imported from tropical areas, and were sold in general stores. They were widely available to both home dyers and professional dyers. The professional dyers sometimes supplied services even to home spinners and weavers. Really, every combination of home and outside professional endeavor went into the providing of fibers, fabrics, and garments in the 1830s.”

DYES

If we look through the brief history of dyes on this website (click the link, and at the bottom of that page there is a link to come back here), we can summarize the preferred colors, methods, and sources.

Putting that together with key extant garments (and modifying that for aging, fugitive dyes, fading, etc.) and the anthropologist’s focus, we can determine in this order a preference the colors and patterns. The following would have been favorites at the time, as they were the “height of fashion” and readily available at reasonable cost. They were the most colorfast, and most could be produced at home or purchases:

Indigo – very dark

Cochineal based reds

Madder Oranges

Madder Browns

Walnut and other nut browns

Prussian or Lafayette Blues

Manganese Bronzes or other rich browns with floral patterns

AND.. natural colors! Unbleached muslin, ecrus and beiges of natural cottons, flax, and wools with prints using the colors above. The print must be specific to the print processes prior to or at the 1830’s, although the Civil War Reproduction prints which are negative dye and roller processes might suffice. For high status depiction, intricate florals and weaves using these colors can be used.

FABRICS

NOTE: This is from the living history site. We will provide the author on request, but are not disclosing names nor locations:

We quote again from the anthropologist regarding preferred fabrics. Silhouettes does have access to fine reproduction silks, flax-based linens, and lovely reproduction printed cottons. The challenge is cost, as silk and linen are much more costly today than cotton (somewhat the reverse of what it was in the 1830’s).

“Often the whole family helped to produce the cloth used for their clothing, especially if the family were rural or frontier.

Sheep were fed and sheared by the men of the household. Wool cleaning and carding were done by young children. Spinning yarn on the high wheel, dyeing it over the cooking fire, and loom weaving of “homespun” fabric were done by the unmarried daughters and aunts. Mothers, sisters and grannies sewed up trousers, coats and dresses; all the women and young boys and girls knit caps, mittens and stockings. Several sheep could provide enough wool for the needs of the average family each year.

When linen was used, the fiber came from the flax plant, which was grown as a field crop.

A quarter acre of flax plants was enough to clothe the largest family. After harvest, the plants were rotted in water to break down the cellulose in the stalks. Then they were “broken” then scraped or “scutched” with a knife, and “hackled” or across several boards covered with sharp metal teeth to separate and align the fibers for spinning. These processes were difficult work, and required strength and determination. When the fibers were all prepared, they were spun on a low wheel, and then loom woven into linen shirting or sheeting, or table linens. Since the only capital investment in linen fabric was for flax seeds, with all the labor being supplied by the family, it was cheap to produce, and was the cloth most used by poorer families, or those on the frontier. It was also the cheapest fabric to buy.

Cotton cloth was readily available, but it was imported from England, or at least New England, and so usually required cash to own.

Cotton was grown in India, where there was plenty of cheap labor to perform the backbreaking field work and then the tedious picking out of the cotton seeds from the harvested cotton bolls.

Spinning, dyeing and weaving of the cotton ~ also hand-done very cheaply in India, or the harvested cotton was shipped to England where the newly developing power machinery could turn it into spun threads and then into woven cloth. England developed a monopoly on cotton and sold it to other countries at great profit.

The early American colonies were forbidden to produce their own cotton fabrics, and were forced to purchase them from English merchants.

Later, after the American Revolution, the growing of cotton and the manufacture of cotton cloth encouraged both the slave population of the southern states and the industrialization of the New England states. But, because cotton cloth production was not a family industry, it was expensive to buy. People who could afford to buy cotton cloth found a nice variety of gaily printed patterns. Cotton fabrics were a favorite gift for men to take home from their travels.

Silk, then as now, was for wealthier people to own. Most silk was imported from China and India. It was relatively scarce and relatively expensive.

Though silkworm culture was experimented with throughout the early days of America, the climates and vegetation were not suitable, and the huge amounts of hand labor required were too expensive for silk production to become established in America.”

From this we can determine a priority in selection of fabric:

- Linen, flax based (for undergarments too. Very comfortable but somewhat hard to maintain – requires ironing!)

- Cotton (if cost is a factor, and easier to maintain with modern wash/dry/iron)

- Silk or Silk/cotton blend

- Wool

Let us look at key Extant Examples of fabrics and prints from 1836 SPECIFIC to draw final conclusions on selection of fabric, color, and print. Emma can then choose the colors and patterns she likes from those that are readily available in her price range (following section on “Fabrics”)

If you sit back and look at these as a whole, you get a very good FEELING for the 1836 time; what it would have been like to go to a social gathering, or to see a group of women in a store together. They are deep, earthy tones with richness through texture and color. While some are light, those seem to be rare as if imported or oddly out of step.

We recommend sticking with the deep reds, oranges, browns, and blues, and perhaps combining with the same colors in floral patterns or stripes.

Key Colors in Real Museum Garments from 1836

Indigo, light and dark

Prussian Blue & Variations of blue/greens

Lafayette Blues and variations of blue/brown with indigos

Madder brown

Bronze

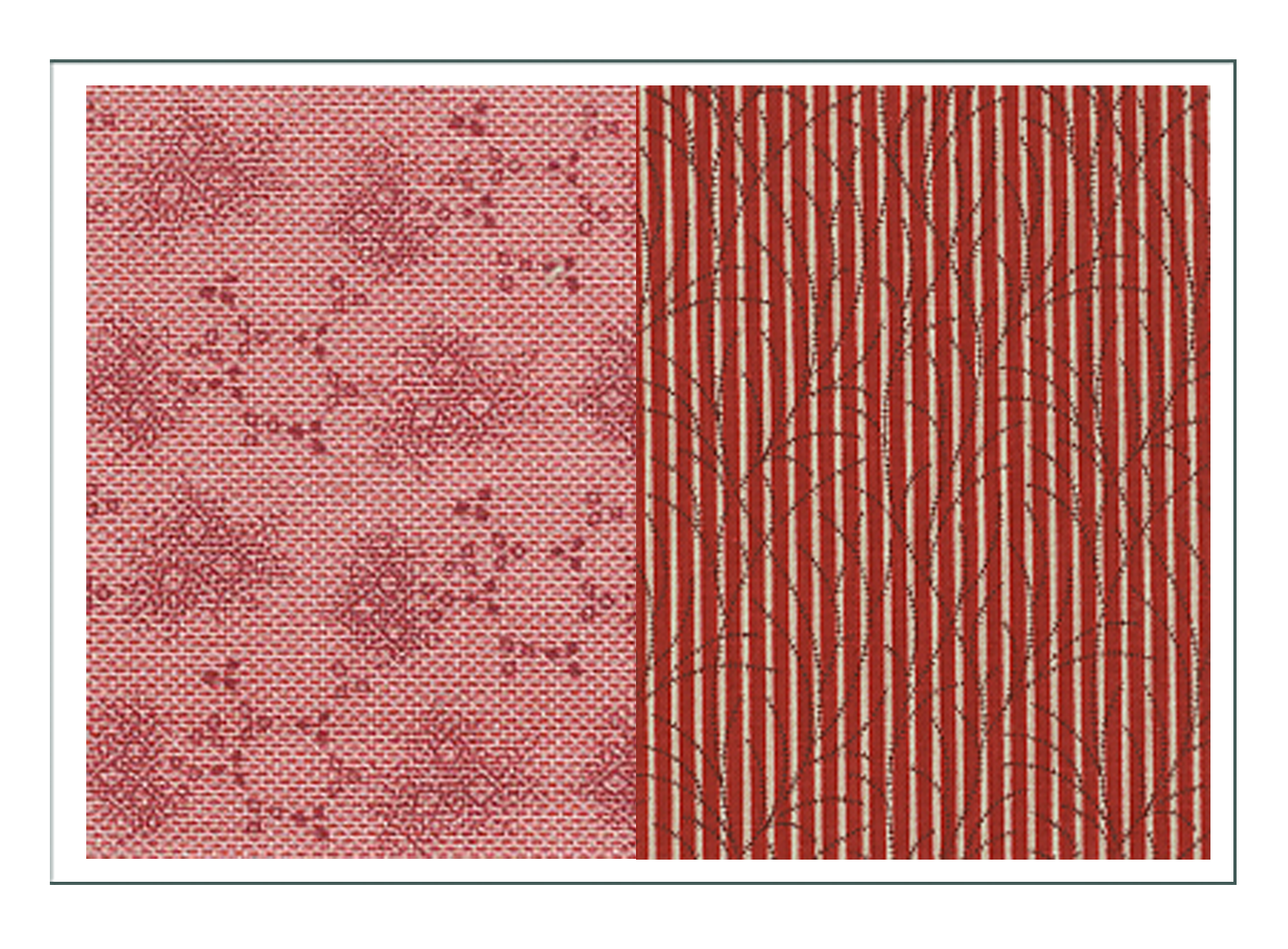

Cochineal Red variations (many)

Madder orange

Orange variations on silk (fabric sample) and on prints and solids cotton or silk

Various natural browns and orange/browns (walnut, butternut, etc.)

Mixed Prints:

Sewing AND Prints

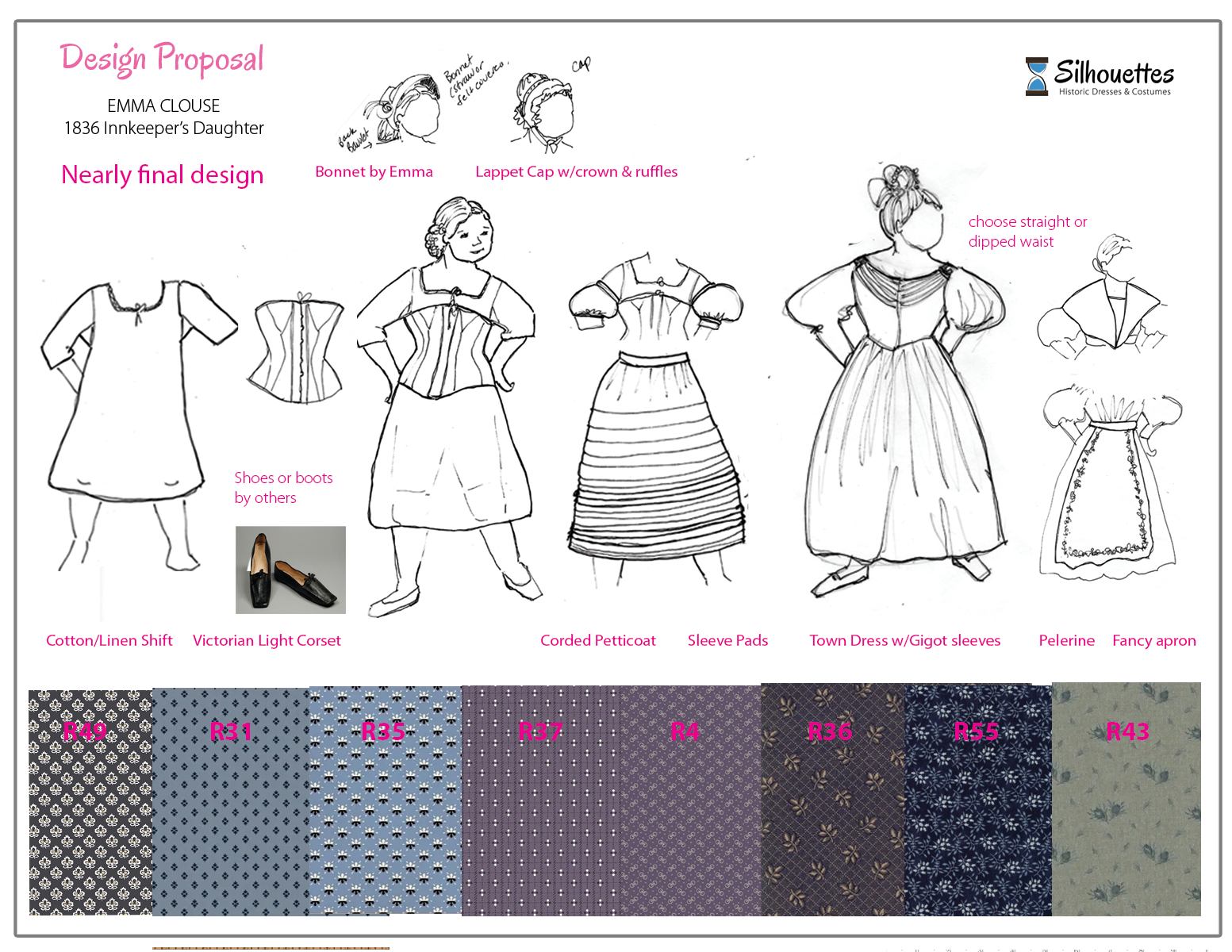

Before reaching out to Silhouettes, Emma had found a previously made 1836 garment. We haven’t seen it, but per their verbal description, we believe their initial purchase was made from this pattern (below):

This is a day dress, typical of a working woman and appropriate to the young and lower class depictions chosen. It would definitely be appropriate. It seems to be a bit later than 1836; perhaps 1838-39 per our research and discussion (above). The shorter length indicates an earlier date, but it is the style of ruching and color construction that indicates later.

It does seem though from looking at the living history farm docents, this is a pattern that is used regularly by them.

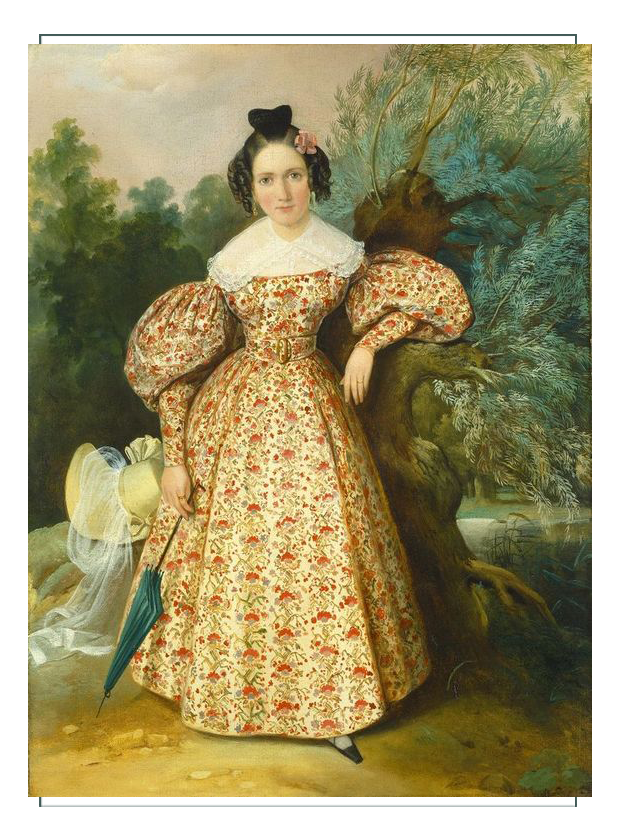

We suggest though considering a Key Extant ensemble for inspiration (below):

Among all the garments shown on the Fashion and History pages, this one stands out for this depiction. The colors, print, overall image, dress design, and details seem just right. Emma initially consulted us asking for an “elegant” garment, yet her character is a hard working and lower class girl. This means the fabrics would be used very economically (and reused), trim would be sparing, and the construction and durability would be important.

What this extant photo shows us is that we can get all those things in a durable day dress. This also is a great indicator of how accessories can be used to change the depiction from a working girl to a middle class girl “going to town”.

(Below) We found historical patterns based on extant garments from other pattern makers. We would like to use one of these as the basis for Emma’s ensemble. They are closer to the correct 1836 details in sleeve and neckline in particular. Many of what you see claim to be 1836 are actually a bit later, and these are closer to accurate.

Since we will drape Emma’s dress for a custom fit, we only use patterns as a guideline anyway. This pattern has a more complex neckline, and includes ideas for ornament to make this into a “higher class” intepretation such as a ballgown.

What we will try to do in the selection of fabrics and final design, is to satisfy the “elegant” while keeping it easy to maintain, durable, and in the price range for both Emma today and what her historical figure could have afforded.

NOTE: description and numbers are for the picture above.

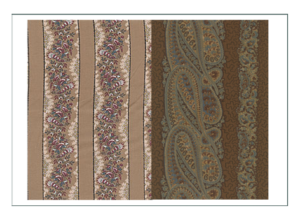

In the search for historically correct fabric type, color, weave, texture, and pattern. We have found these available:

IN SILHOUETTE’S STOCK FABRICS (at price quoted)

CAN GET EASILY (at price quoted)

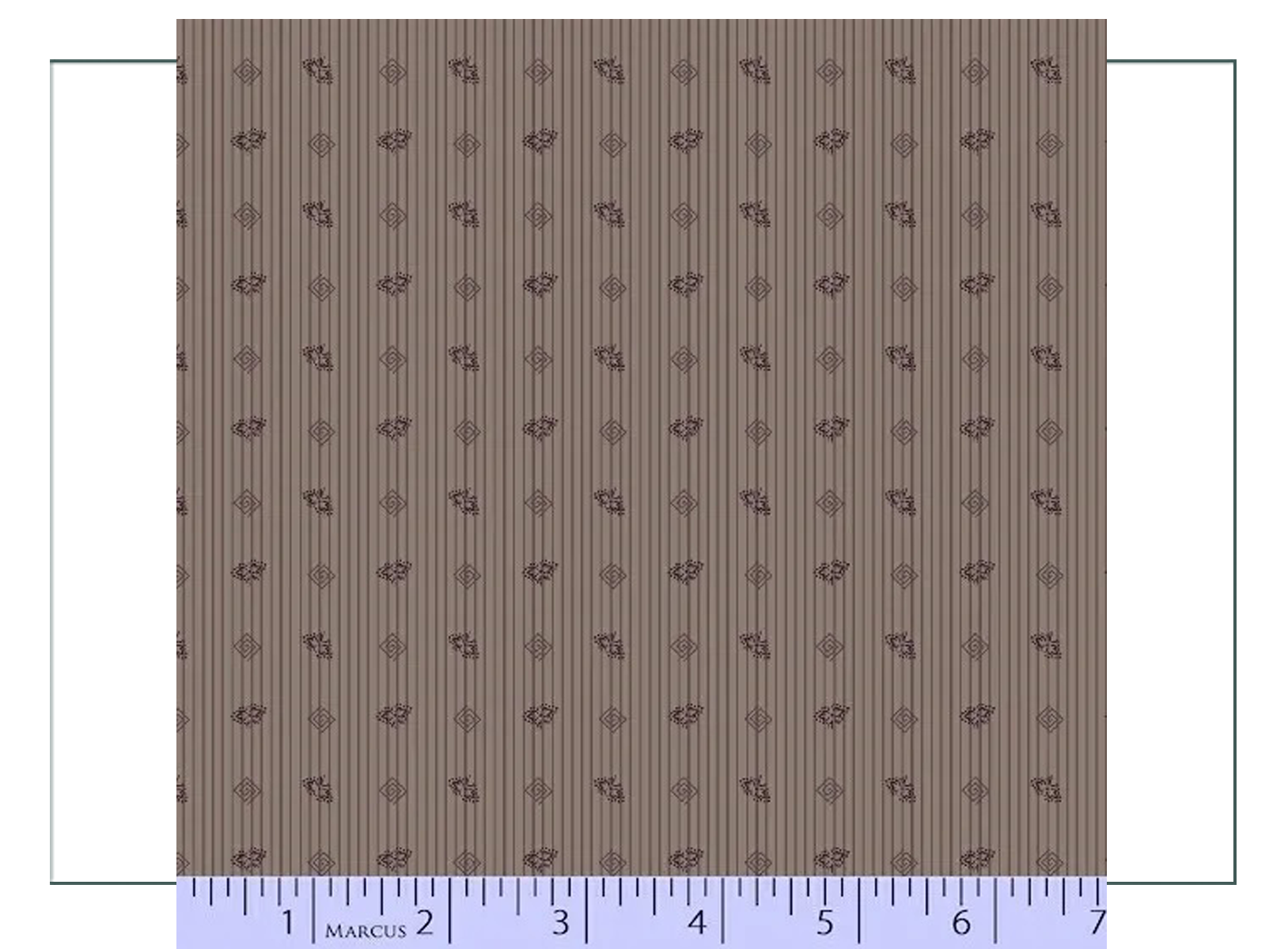

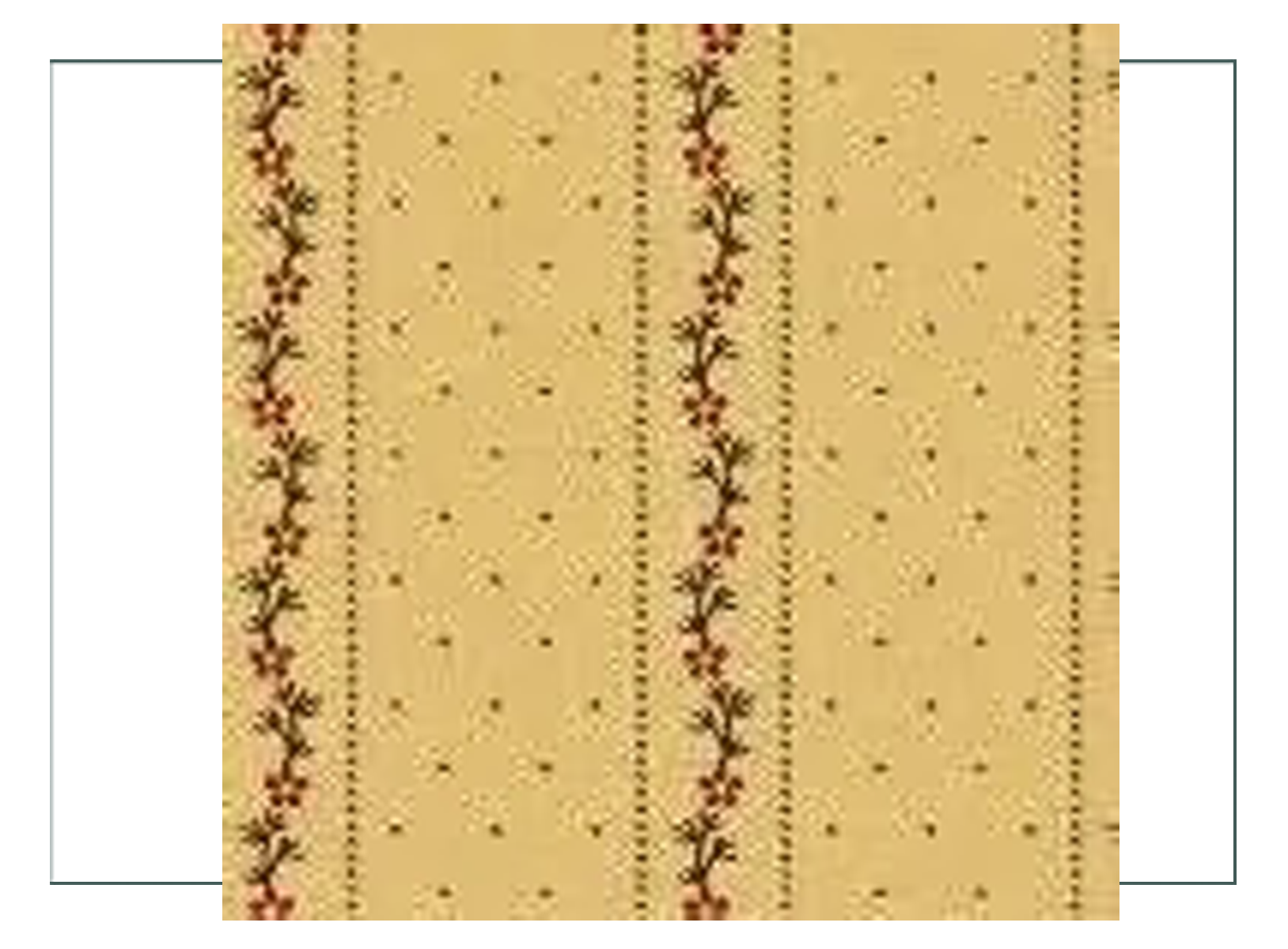

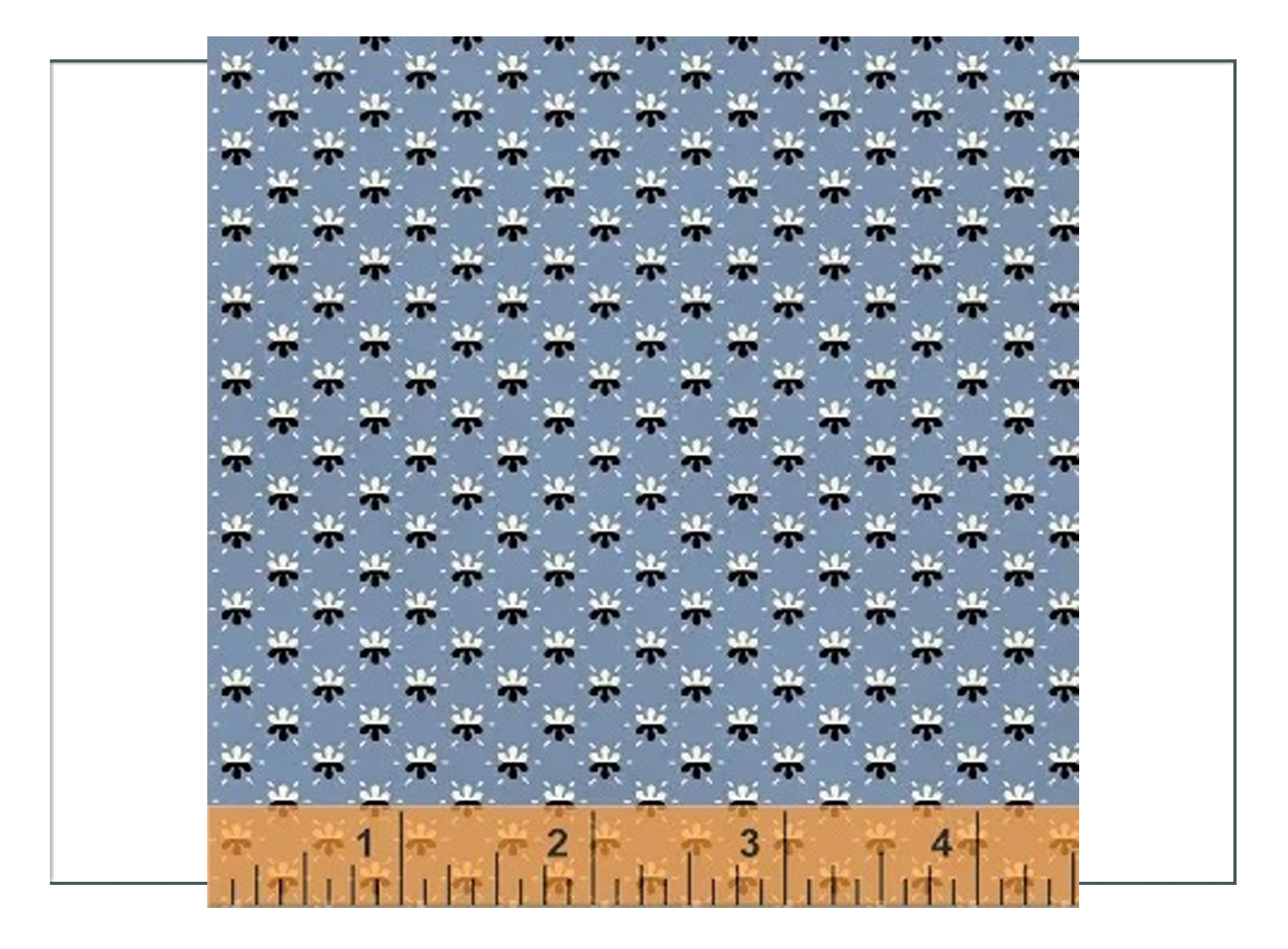

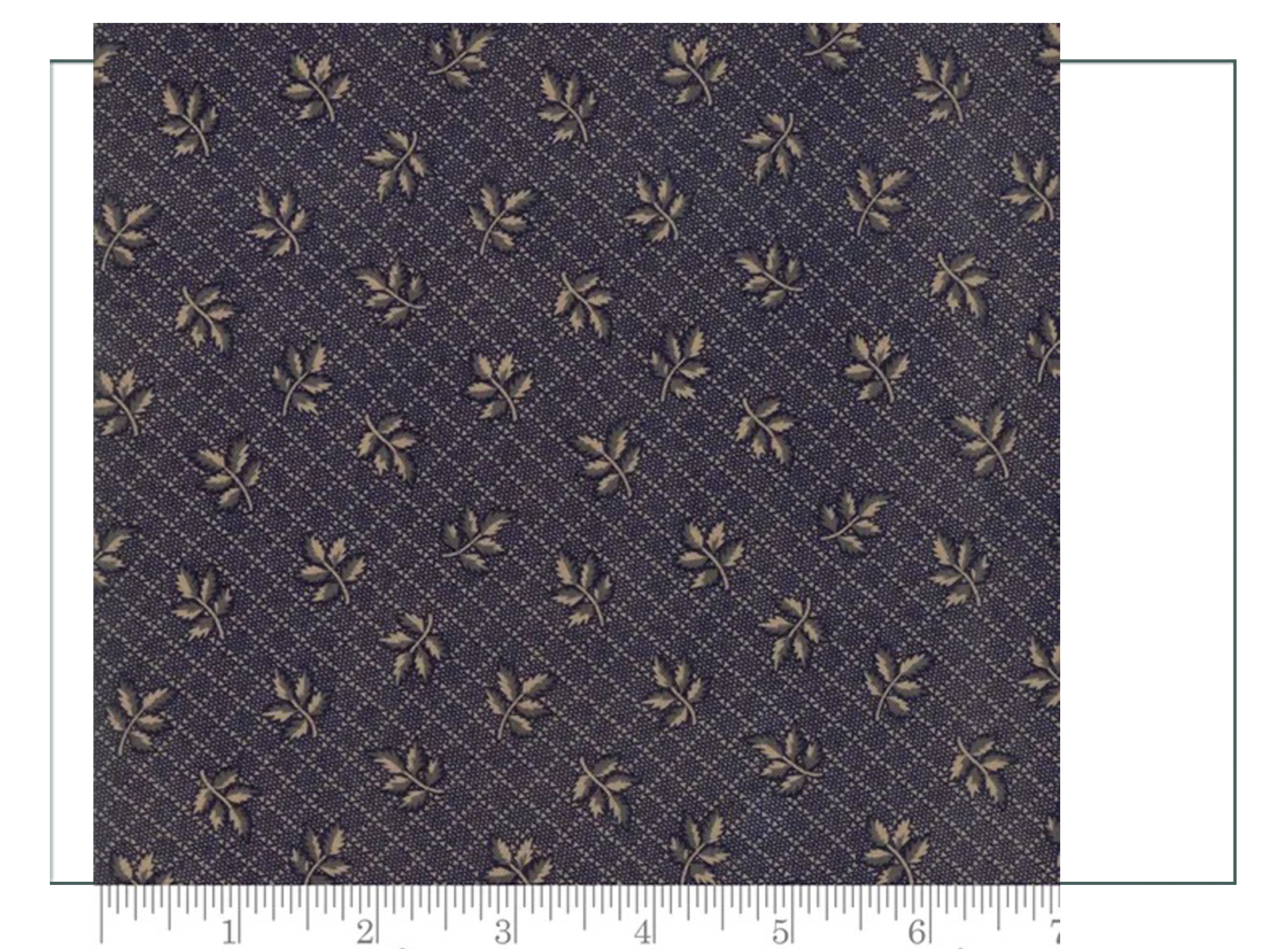

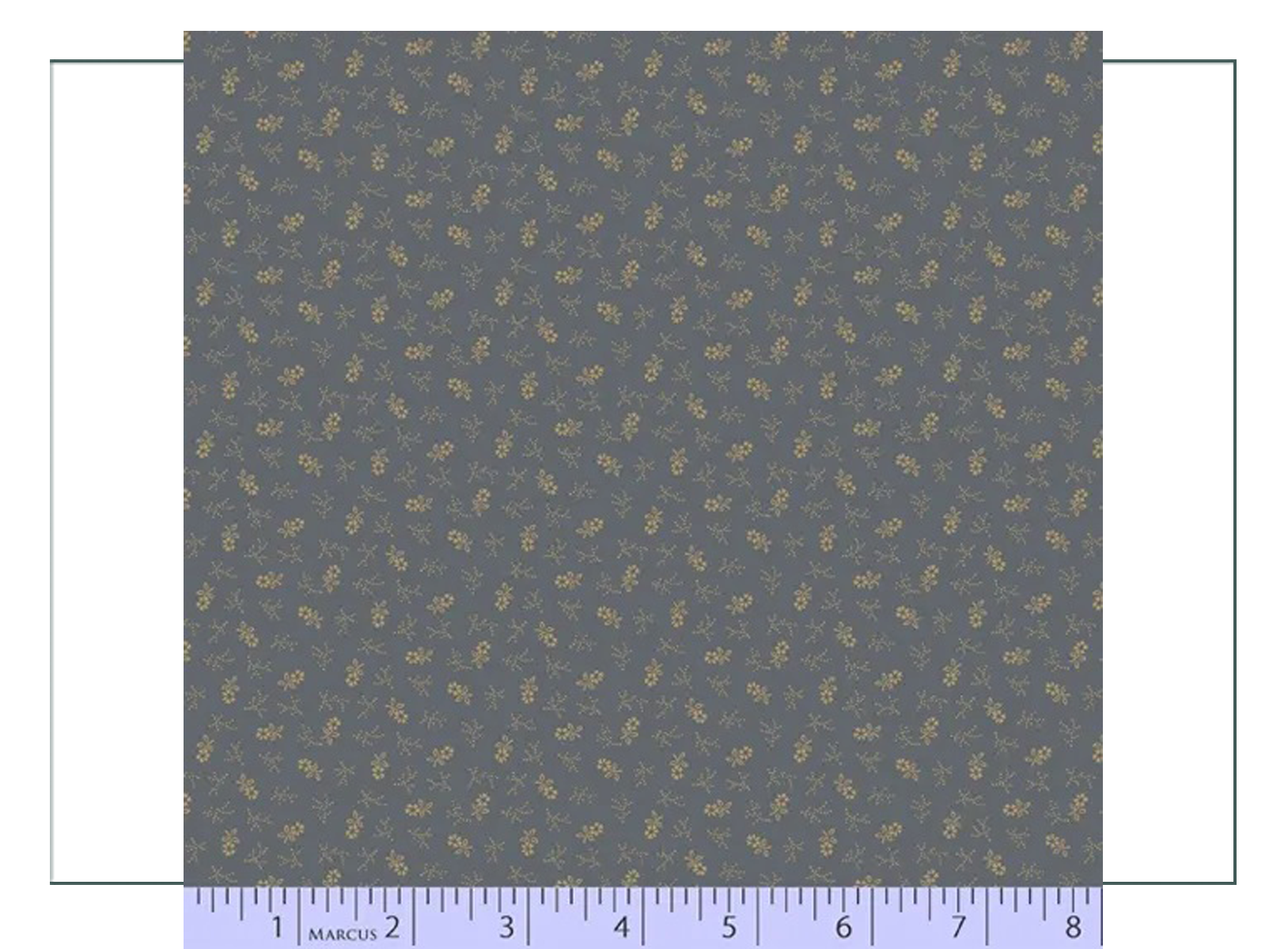

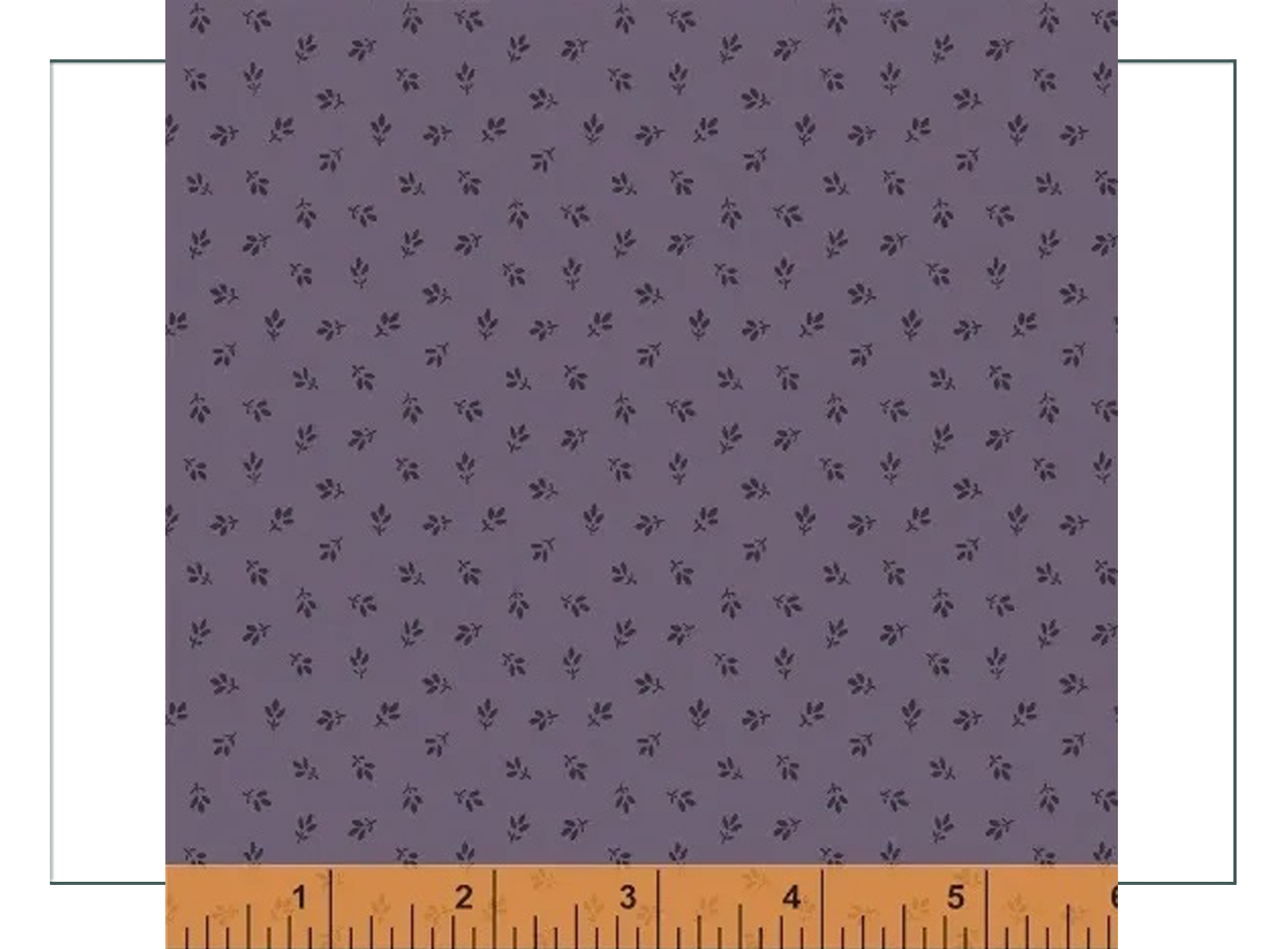

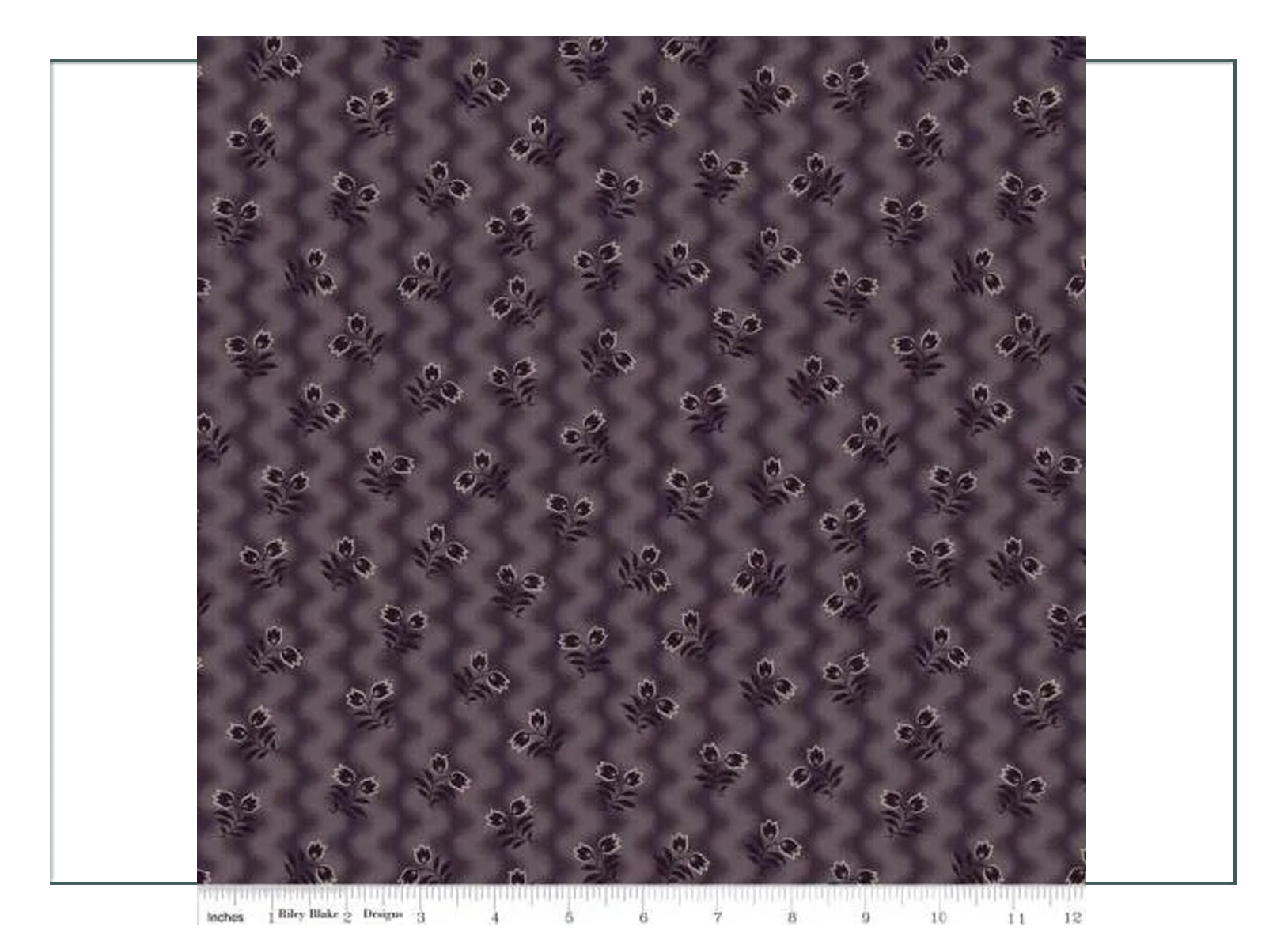

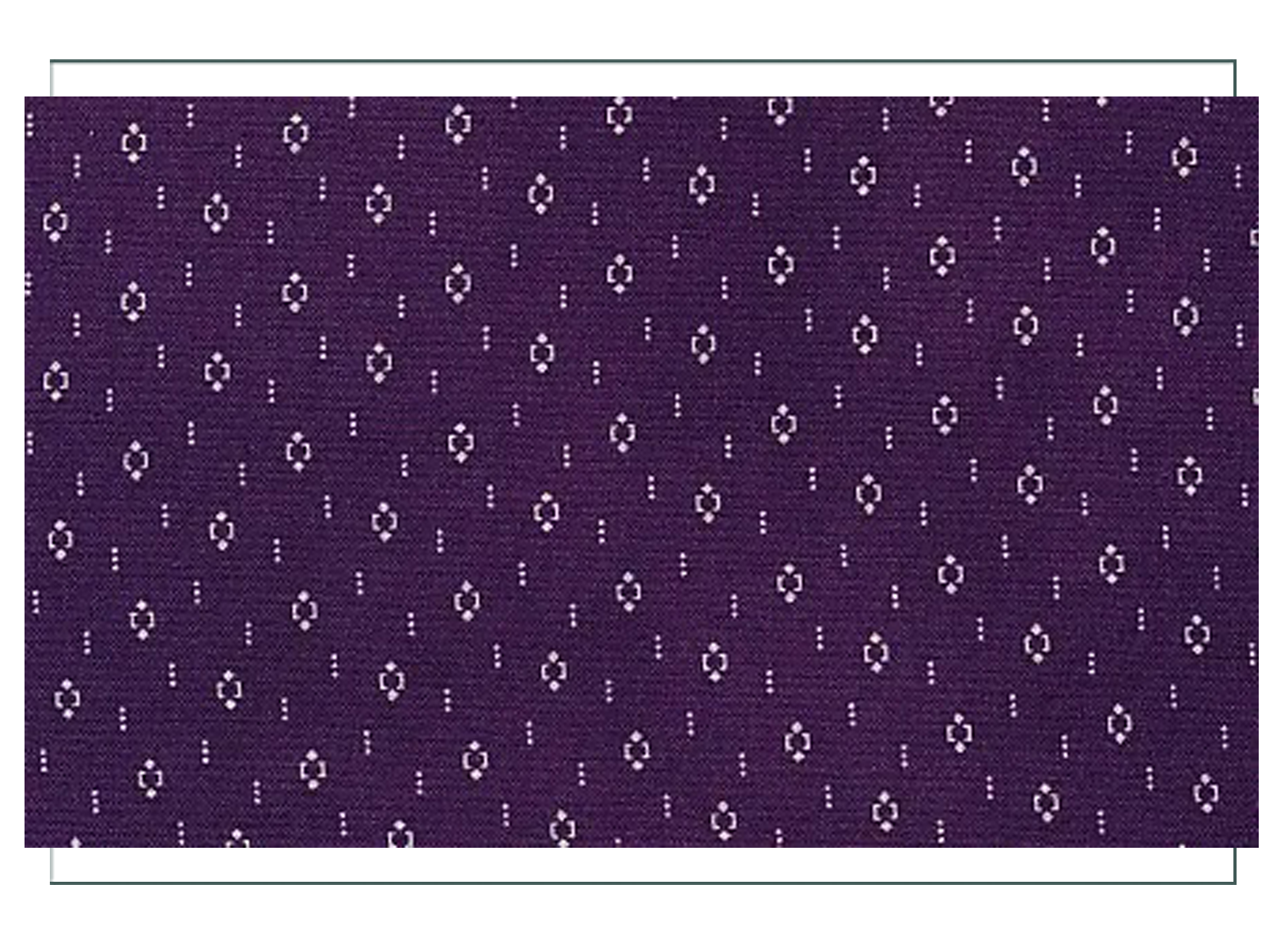

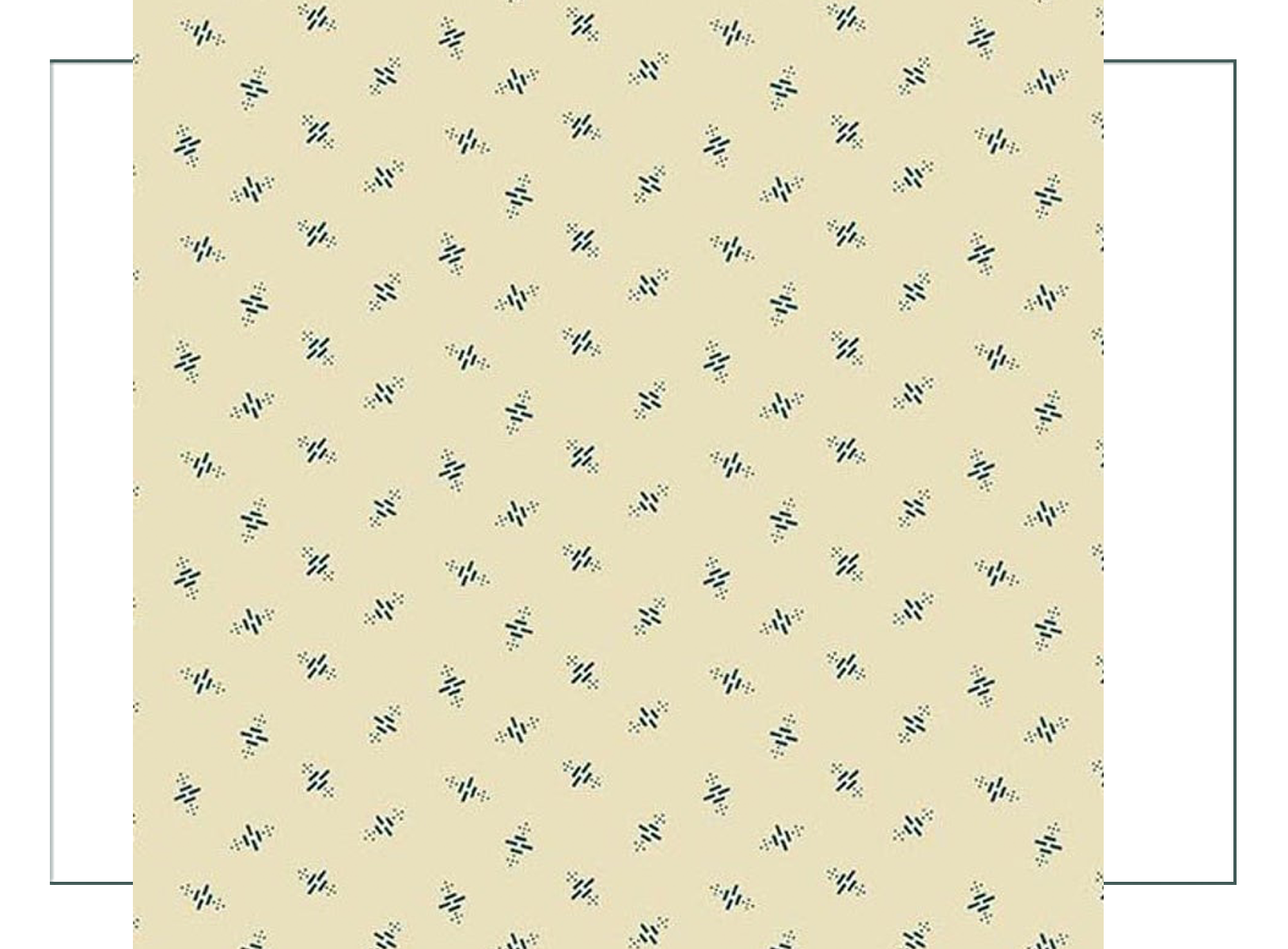

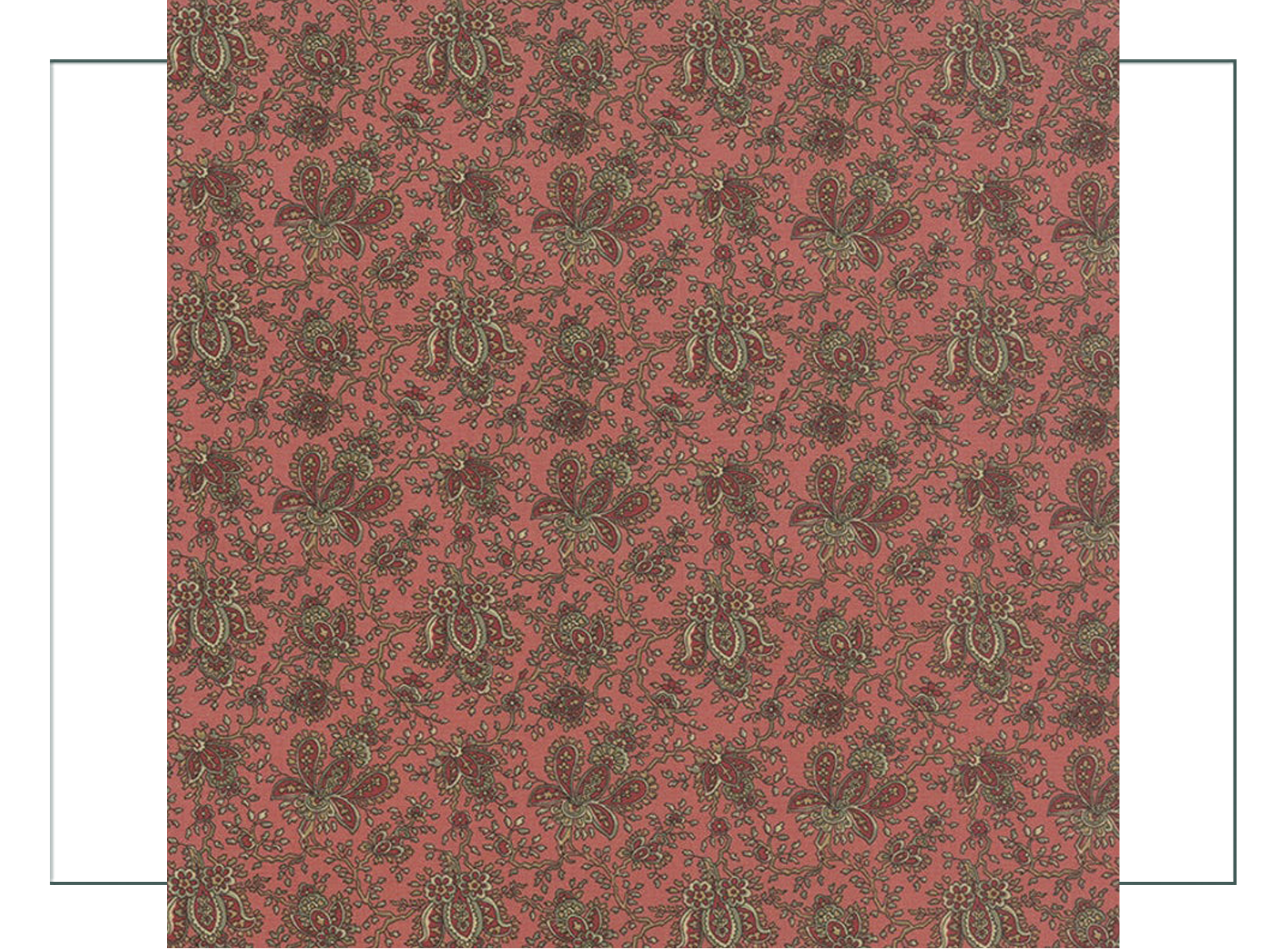

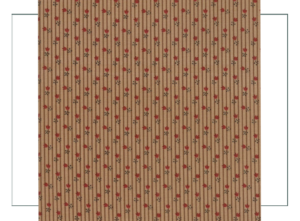

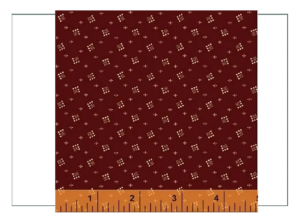

Note some of these will coordinate with others in the group. ALL of these are appropriate to the dyes and prints of the day. Many are actually 18th century designs and print methods. All of below are durable and easy to maintain (a bit of touch up ironing perhaps) cotton unless otherwise note.

1830’s SPECIFIC REPRODUCTION FABRICS (also easily obtained)

LINEN EASY TO OBTAIN (price upgrade all)

SPECIAL REPRODUCTION FABRICS (historic cotton chintz fabrics; price upgrade)

(Of course we like the expensive fabrics…)

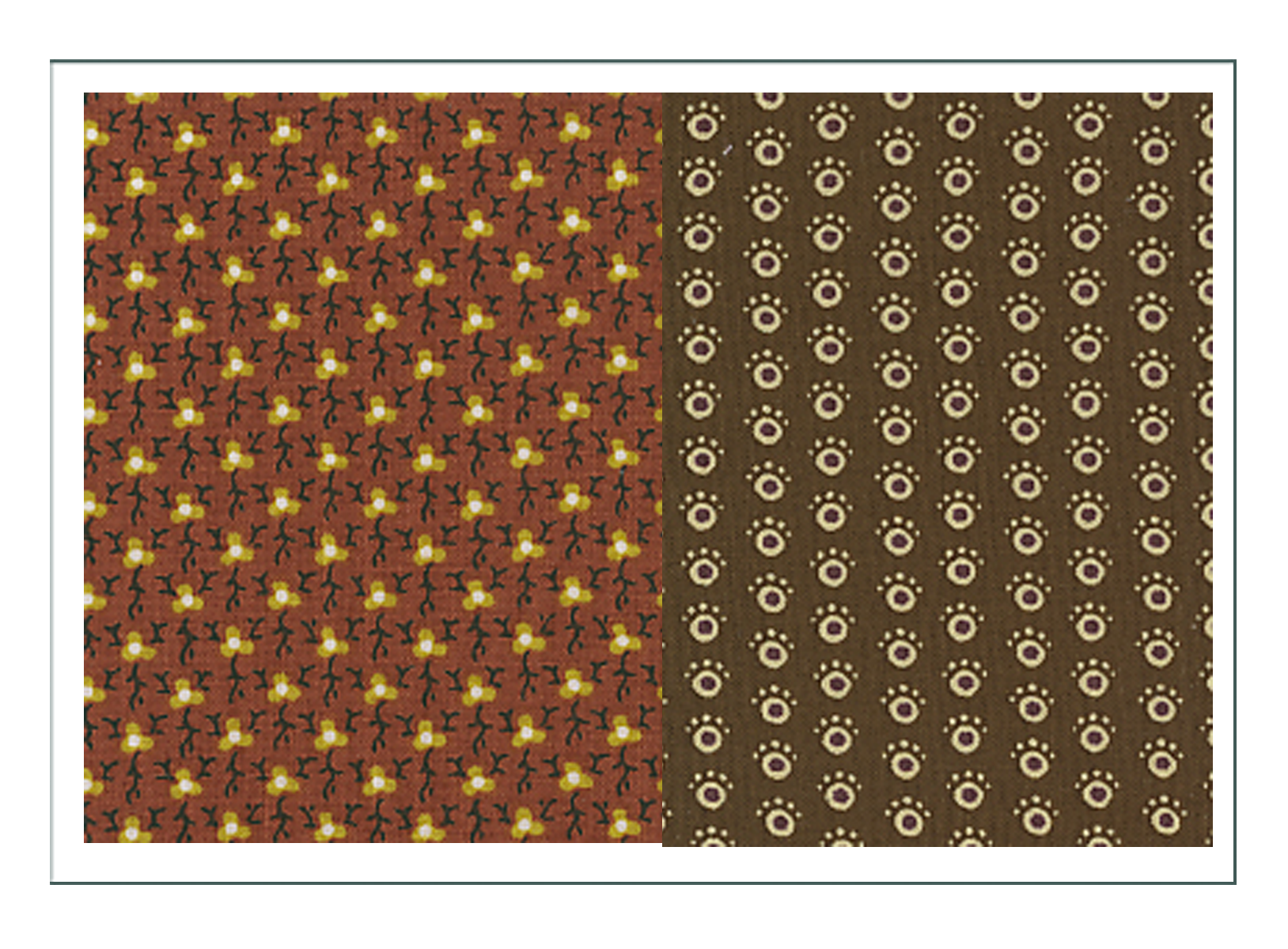

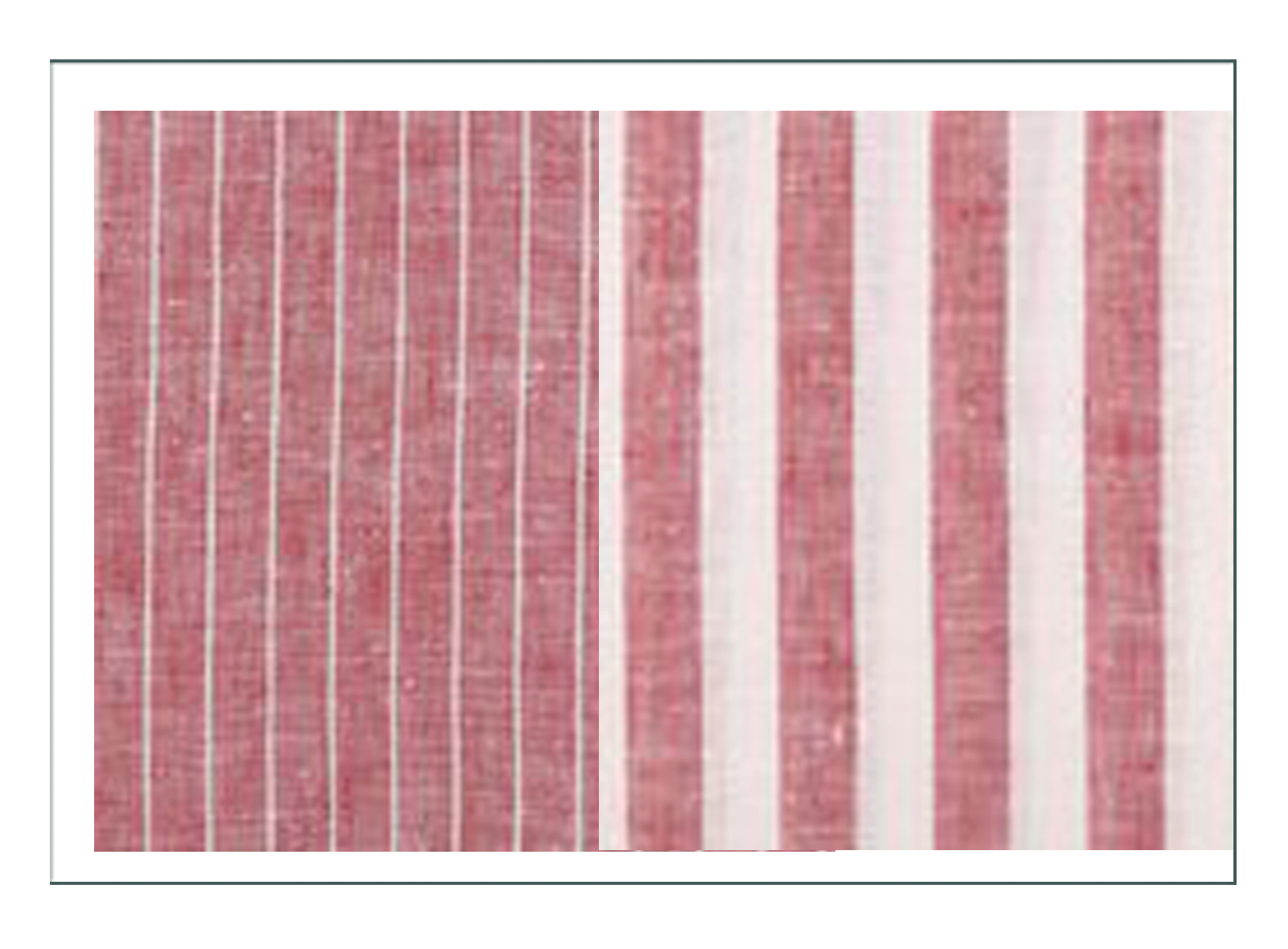

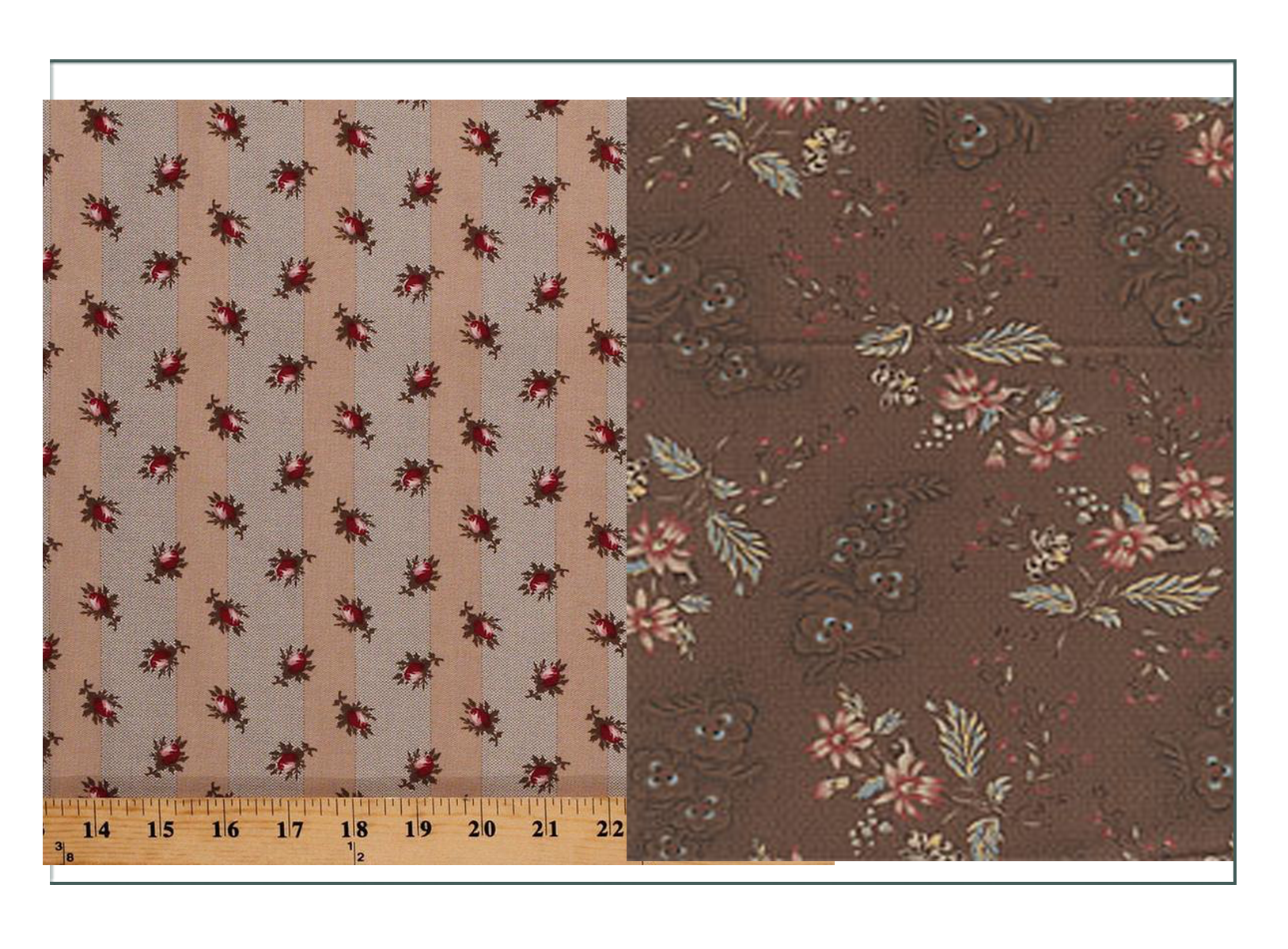

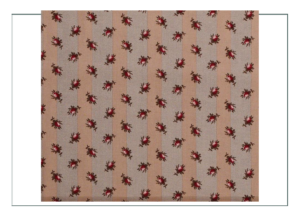

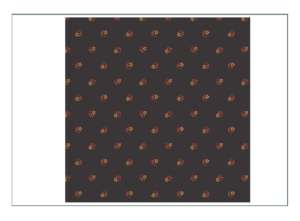

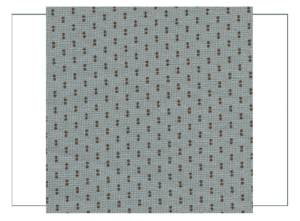

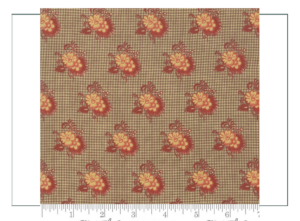

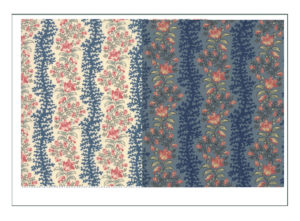

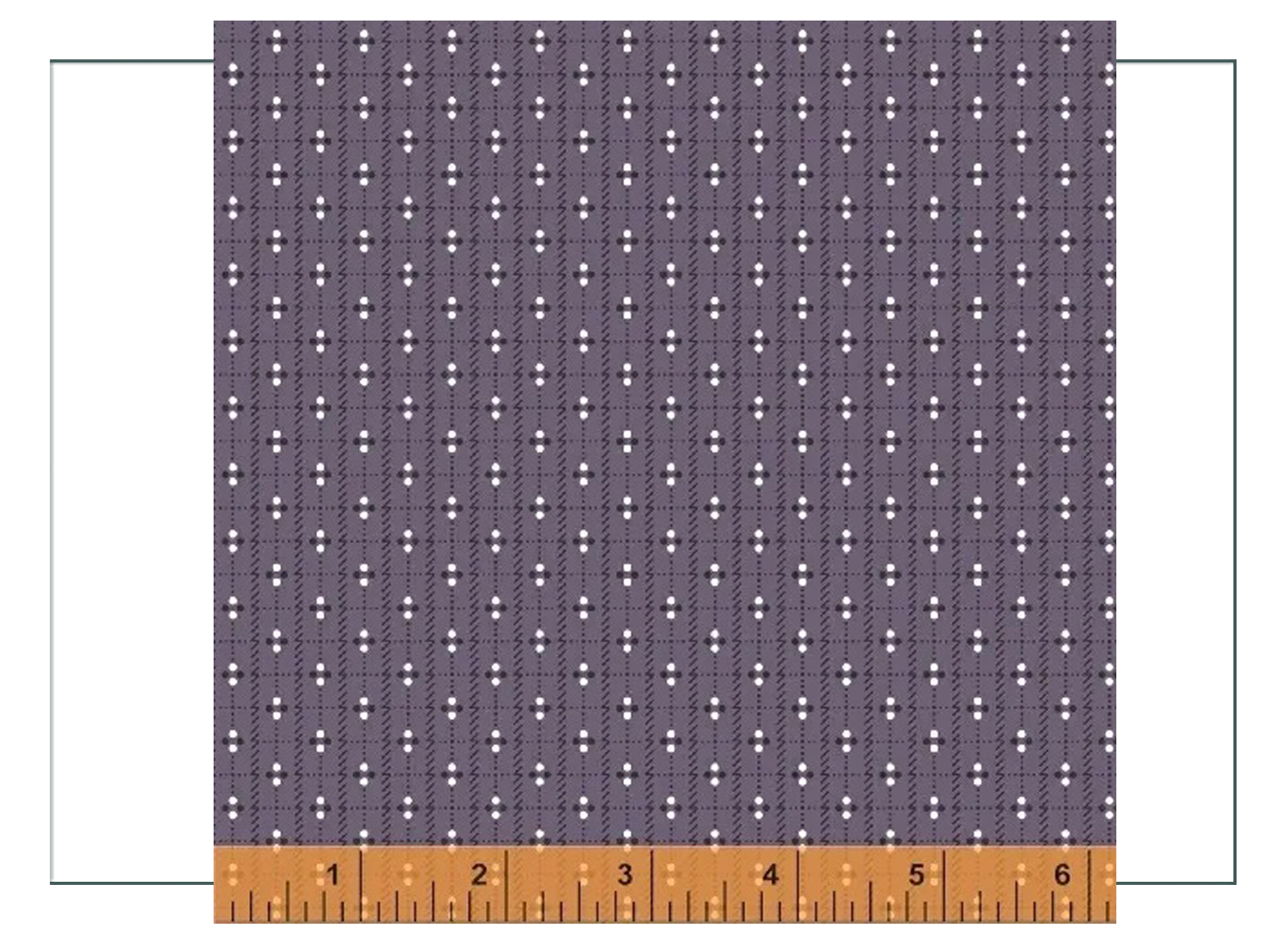

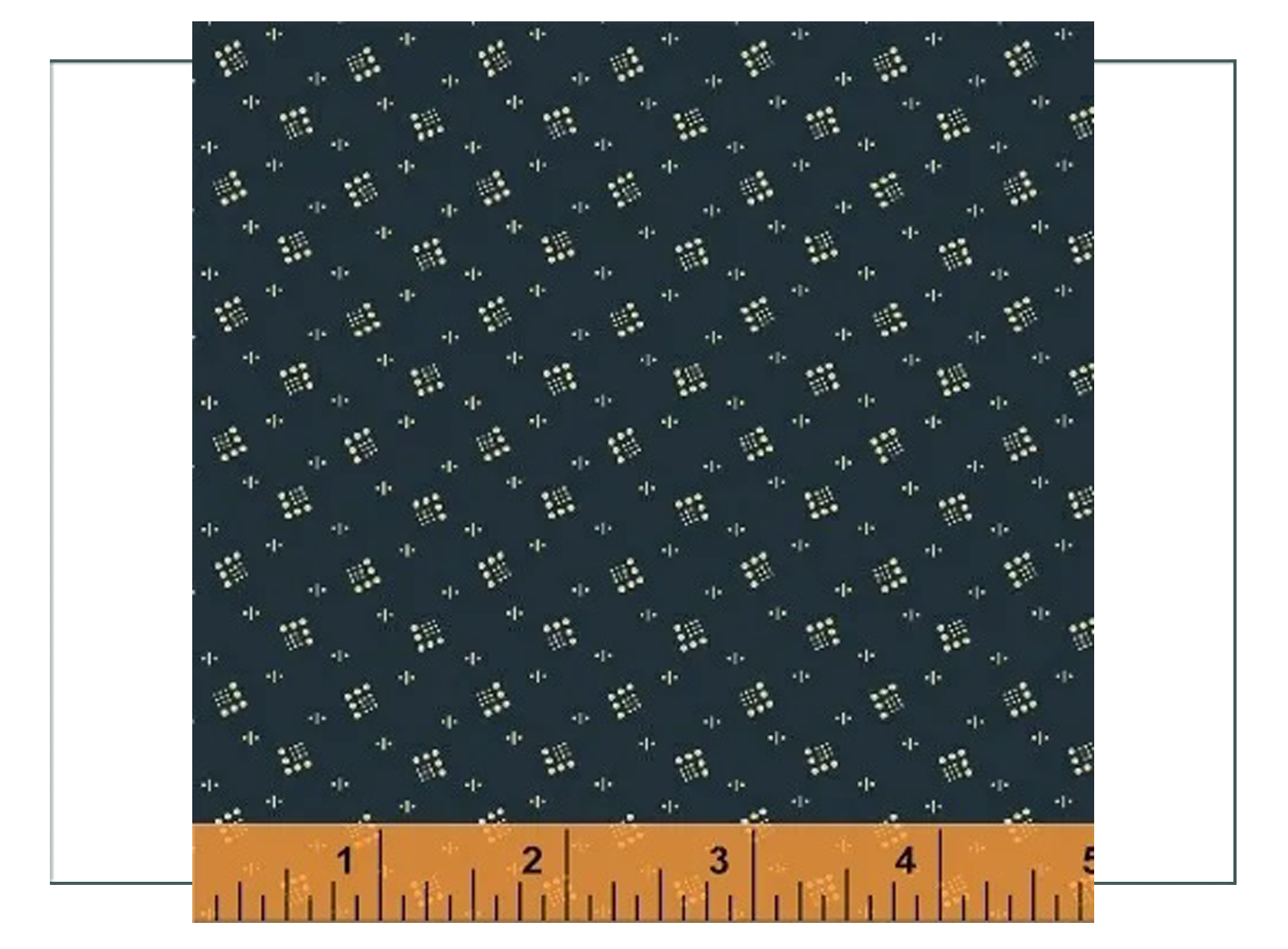

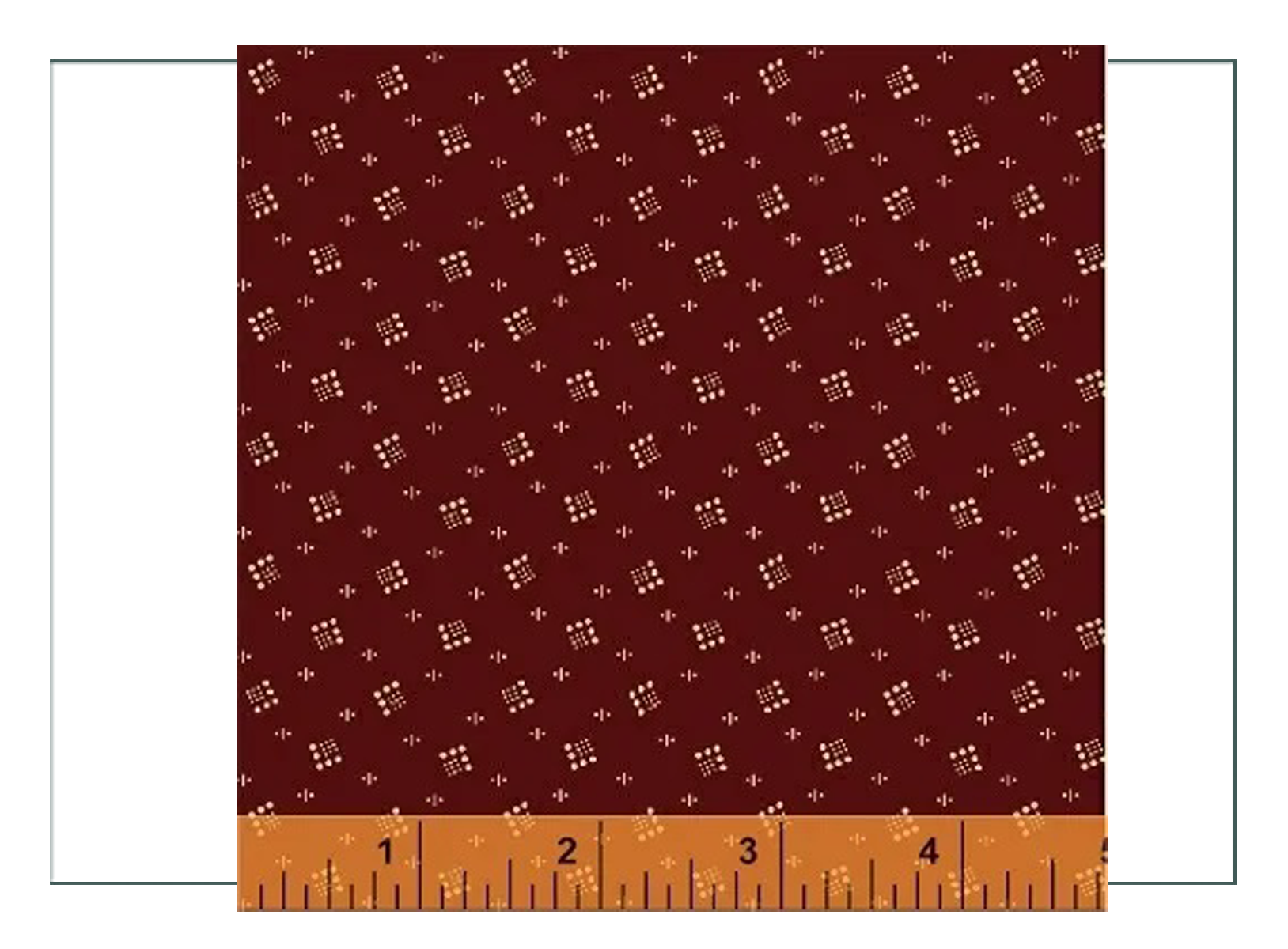

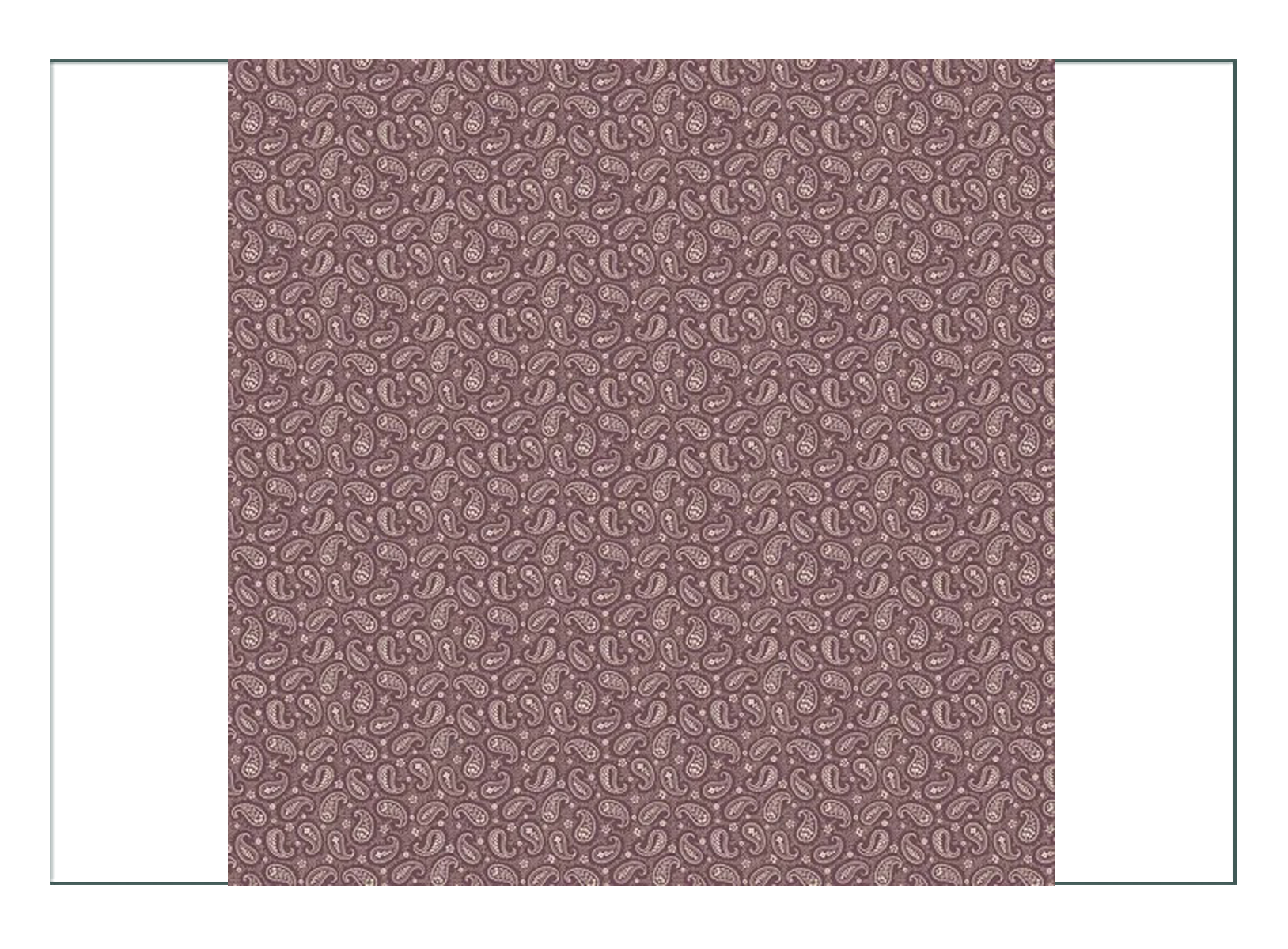

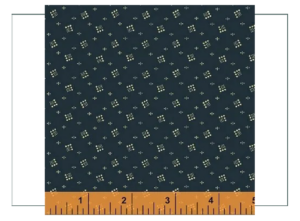

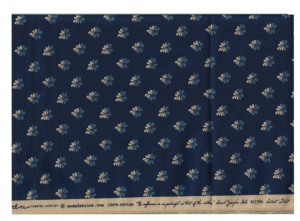

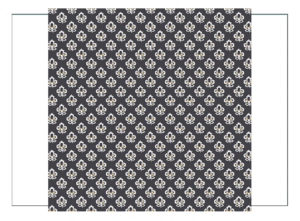

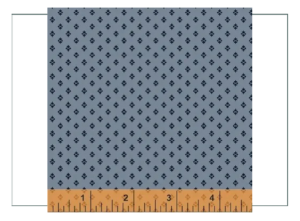

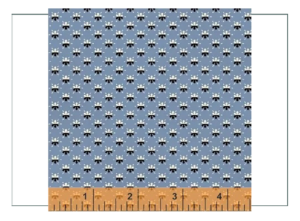

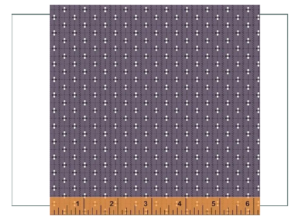

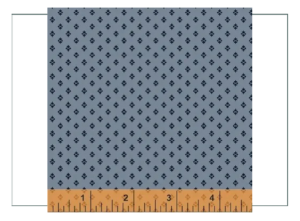

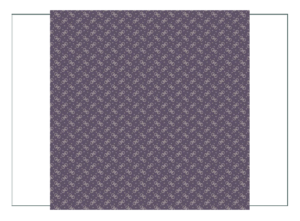

You will note most favorites are the dark and rich colors, specific to 1836. They are the madder, cochineal, and deeper blues. These are what a working woman would wear in a day dress. We are keeping these formatted small, because these patterns need to be read from a distance for the overall impact. They are shown very close to the order of preference. Designer’s decisions are based on historical accuracy for color, print method, print type, fabric type, and suitability for the pattern above, and only a bit on personal taste:

The others are lighter for a dressier ensemble, and not appropriate to working in a barn or waiting tables:

Now for Emma’s response to the selections above including what she has found, what she likes, and if she would like us to keep looking.

The next step will be finetuning which undergarments we are going to build, getting fabric samples to present to the anthropologist for approval, and design sketches to create the original garment. First we need to collect her information and examples.

More Samples after Emma’s Input

She’s looking for purple or blue! We found an exciting new source for Civil War Reproduction Fabrics (in Suzi’s hometown!) From there and other sources, we add these. While purple is not shown on extant garments or our color and dye analysis, texts indicate dark purple was a favorite in the 1830’s. We think the key is it has to be a purple generated of the indigo and one of the reds from the natural dye groups (cocchineal, madder, etc.).. which means a deep bluish purple.

Along with those, we found others that would be very accurate and lovely for this ensemble.

Look up Close; Look from Afar

IMPORTANT: One must look at these from far away which is almost more important than up close. Colors and patterns like this will change depending on if one is close or far.

What to Look for in the Print Process

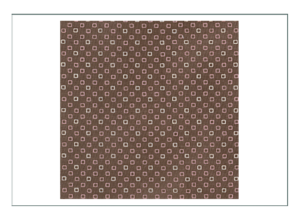

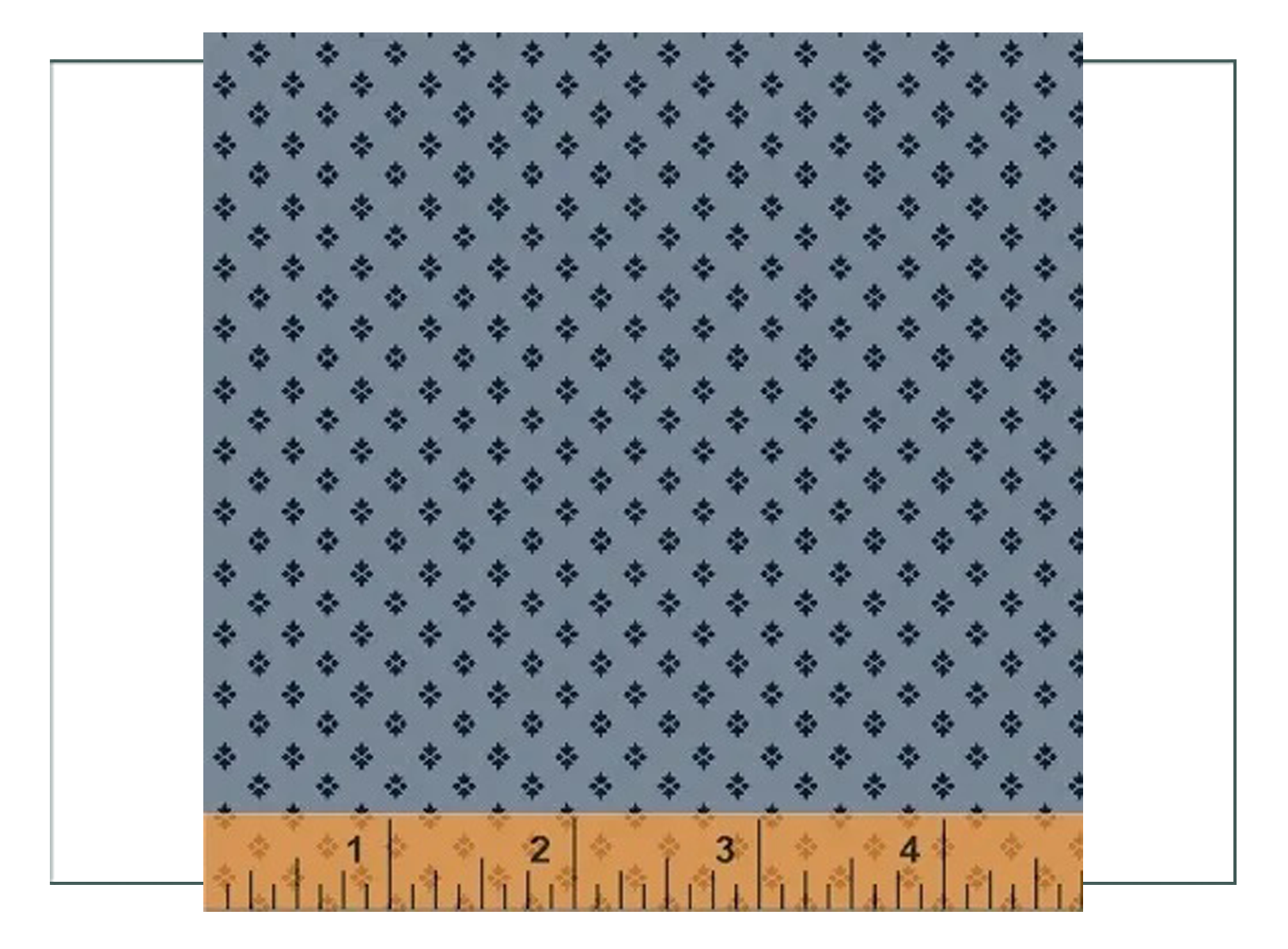

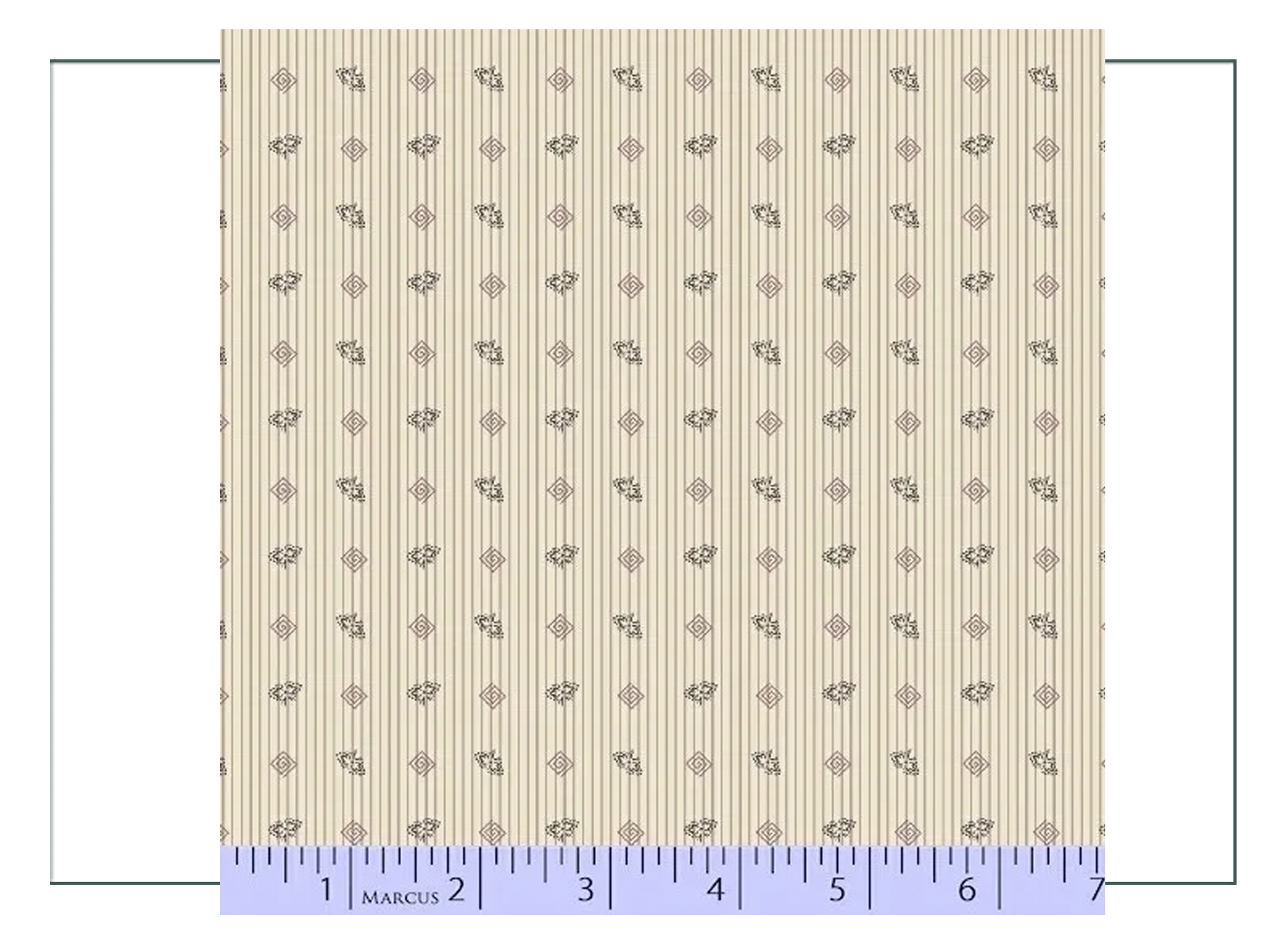

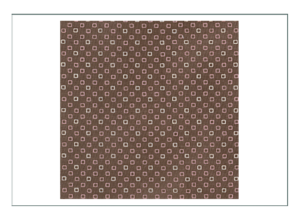

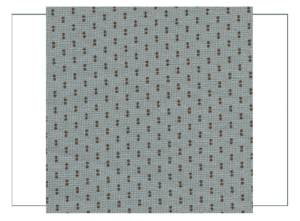

We studied above quite extensively which colors and dye sources to look for. Equally important, the second thing to look for is the PRINTING PROCESS. It needs to be a “roller” which was the innovation of the day (so everyone just HAD to have it!), which means a regular repeat of a very consistent pattern.

1. Designs must small and repetitive, and in one color (think if you cut into a rolling pin, dipped it in paint, and then rolled that on paper.. it would just make that cut over and over again as one color in the same place every time).

2. The design must be simple. The designs that are complex or have multiple colors that are PRINTED are 1850 and later – the more complex the later. Most of the complex designs at the time were WOVEN into fabric – like lovely silk damasks and brocades of the 18th century Court apparel, so many colors were available. We are looking for printed fabric for this project.

Some of the following have the same color, tiny prints, and constant repetition over and over again, and seem correct for 1830’s, but they are a bit later towards 1860 (like R36 and R53) The difference is that the colored small item is less INTENSE in color – what this means is the dye process was more sophisticated, and could “hold back” some of the dye either by chemicals or physical processes.. thus making a print that is dark and light but the same hue (like R43). R44 is a particularly advanced process for the time.

The space in between images must have some room too. While there were of course prints that ran the design close together like R40 weeping willows paisley, these would have been more rare given the size of rollers at the time which had to make the “curve” as the fabric rolled under. They would more likely have been “block printed” (flat down by hand), and thus not only an older type of print, but also more costly. The tight roller print would evolve quickly into the 1860’s, so prints like that are most likely a bit later than the 1830’s, although still “passable”.

3. 1 or 2 colors is fine. The number of colors used makes a difference. One is most accurate although two colors are fine, although that would be less common for a working girl, as long as they meet the same criteria: small, repeating (with a small space in the repeat), and of the natural colors available at the time.

4. Patterns may be “fuzzy”. The dye process on some fabrics was not quite “exact” until the late 1860’s, so fabric designers earlier than that often printed a line around the image – say a dark blue around a light blue leaf – to try to “tighten” it up visually; to make it appear to be accurate. This allowed them some room for error if the rollers of two colors didn’t exactly line up straight.

That’s why you find prints like “R35 Crazy for Melbourne” (which, by the way is a Museum in the northeastern U.S.) having a high contrast black and white over a color. They liked black and white for this reason – it tricked the eye into seeing a really sharp and detailed print even though the print wasn’t exactly sharp or detailed (look closely, and you’ll see they don’t line up EXACTLY).

5. It can be tricky with the overlapping of colors. You may see 3 colors on the fabric, and think it is too “modern”, because we just wrote it should be only 2 colors. In reality, the second color is the same color as the background dye, only applied as a design over the main color – making it a 2 color print like R32.

A print like R31 below is really a ONE color print. Same color; same dye – just applied one on top of the other in different saturation. Most likely they dyed the fabric first, and then ran it through the roller to print to get a sharp shape like R31. More likely they ran it through as one, which is why they got “fuzzy” prints like in R43 which is actually a reproduction of an older fabric, even though it appears to be a sophisticated and later Victorian fabric. Again, look for the sharpness of the edges of the patterns, the number of colors, the closeness of the design, the colors uses, and:

6. Watch for the types of imagery used. You will see 18th century and earlier imagery – medallions, trefoils, paisleys, and lots of dots used (dots were easy to print on a roller) that had been popular for a long time. Paisleys and trefoils in particular had been favorites for centuries, and they were starting to become popular at this time, although not as much as they would after Queen Victoria made them so.

EXCEPTION: Such as ZG, which is an 18th century print on cotton chintz – there are elegant and complex fabric prints that were available. These were imported, and hand or block printed at great labor and cost, so there are exceptions to the “rules” above such as these and others shown in the first groups – paisleys florals, etc. We have only selected a few that might suit a lower class interpretation, and are intentionally ignoring the many gorgeous woven and embroidered fabrics of the time. This is intentional because of the economy of the characters being portrayed and for Emily herself. A few that are prints can be found at reasonable price, but they are a cost upgrade.

New Group to Consider – Fabric Prints (no upgrade: all at proposed price)

Following are not necessarily “Designer Picks”, but the fabrics from all above that meet the criteria stated above for. These are not in particular order:

- Dye color(s)

- Number of dye color(s)

- Print pattern

- Print type – imagery

- Closeness of images

- Print process

- Extant (real garment) examples seen in similar

- Text references to such

With Options

(proposal and costs sent privately)

After Meeting to Discuss and Measure!

Emma’s favorite fabrics (to get samples to present to the anthropologist) in no particular order:

A trend is observed! It appears we are headed to purple and blue hues: dark with white small roller print. 3 have “resistant dyes” which we will discuss as they are a bit later than 1836, but still feasible. Surprisingly, designer is liking “Shelburne”, “Adele”, and “Jamestown now. It depends on if Emma wants contrast and “sharpness” like those 3 provide, or a more muted and blended look like the others when seen from a distance.

Narrowing down selections and add ons after meeting:

We added the R40 fabric because we think Emma might like it when she sees it in a sample. R36, R55, and R43 appear to be a resistance dye process which the anthropologist may think is too late in time; more like the 1850’s-60’s.

This dress selection is actually 1830-1836 (not later as we thought before), so it is perfect for this depiction.

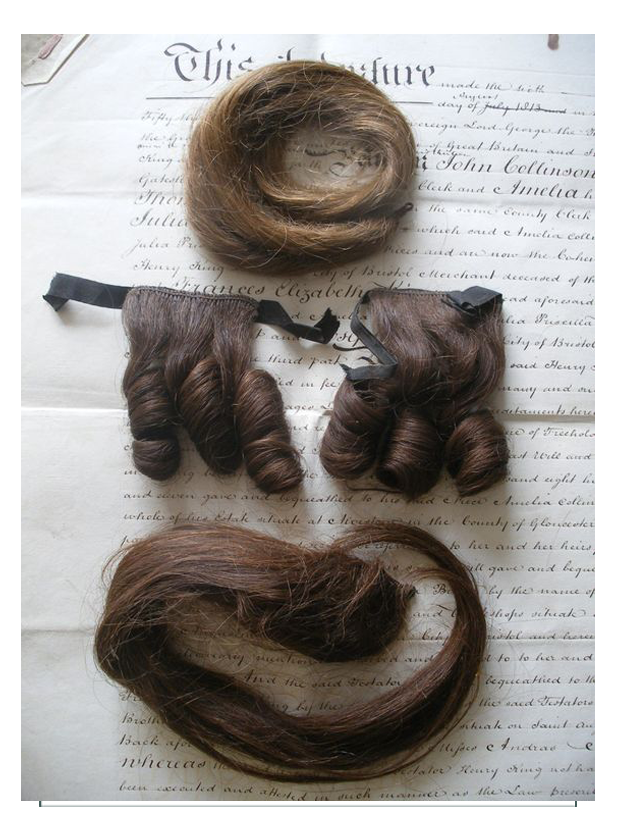

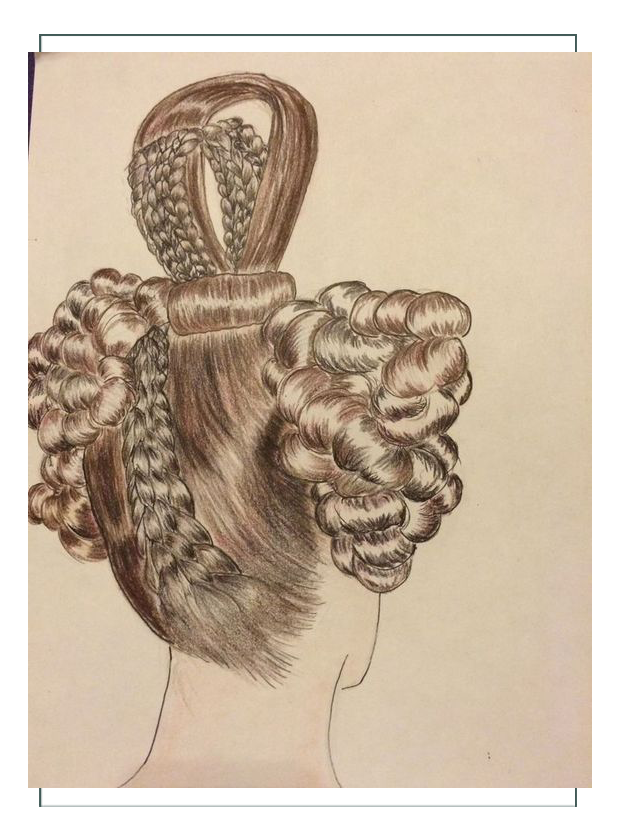

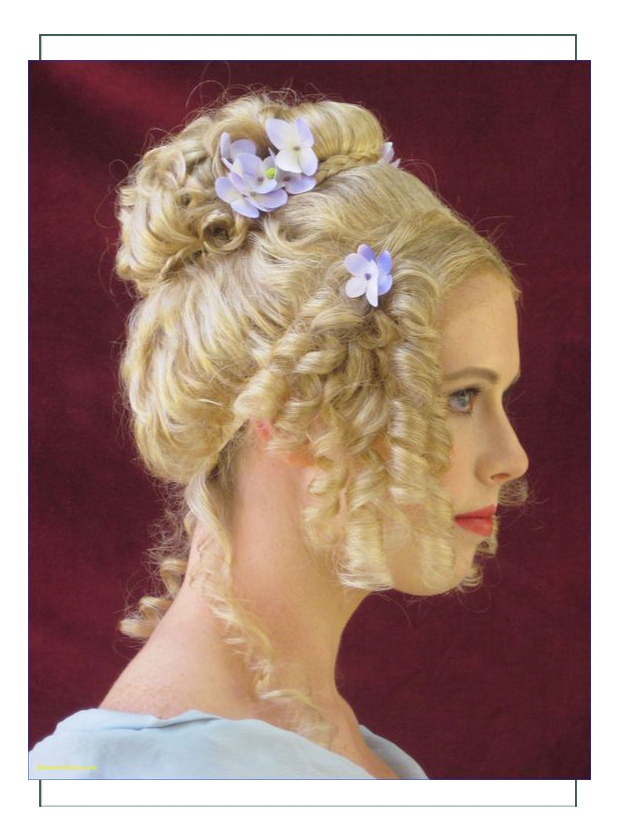

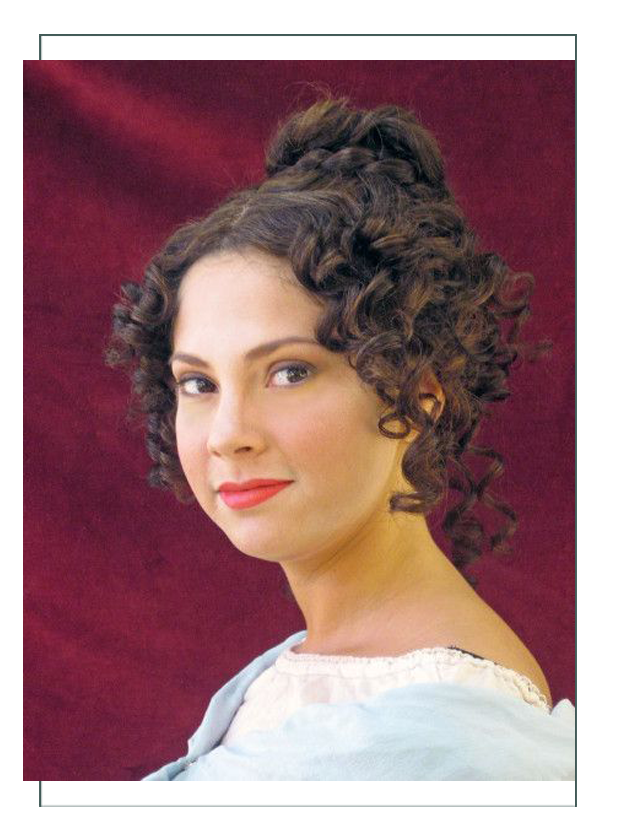

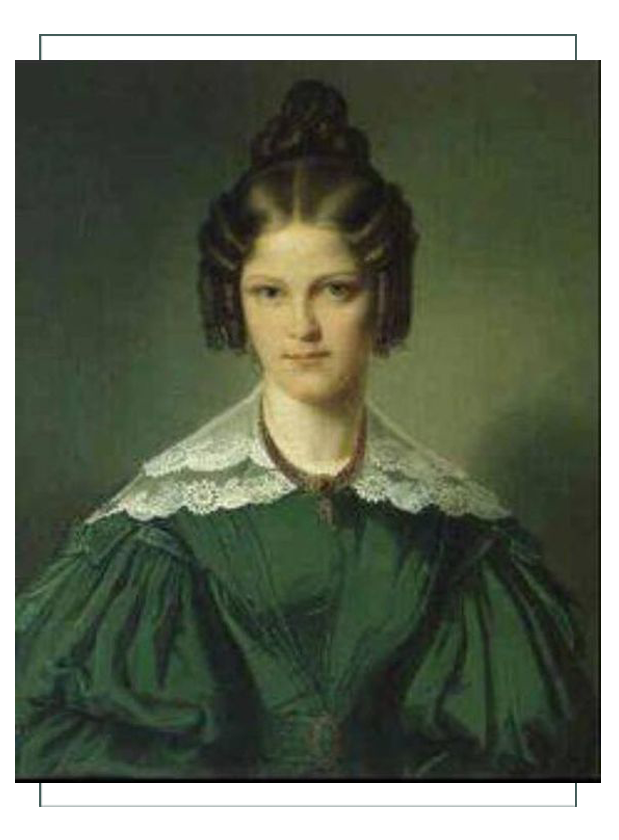

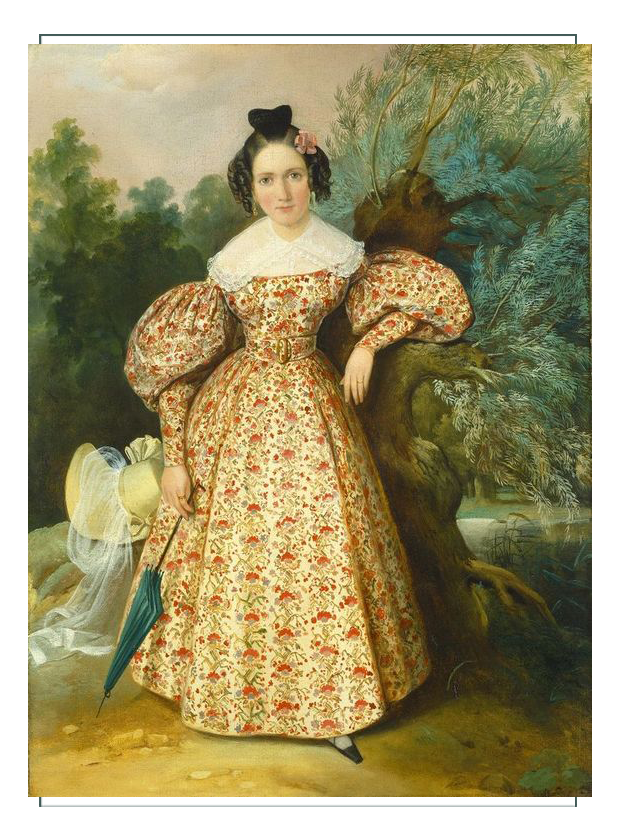

While waiting for fabric samples to come, Emma is researching how to style her long hair. We have a regular supplier for custom wigs and hair pieces: thehistoricalhairdresser

Rather than mark up and resell, unless customer requests, we send customers to the salon owner, Fleur there, who makes the most FABULOUS high quality synthetic and natural hair wigs in the WORLD. She has in stock and available full head wigs exactly as Emma would need (if Emma didn’t already have the perfect hair for this Emma of her own), and/or the hair pieces for sale. We will help Emma match her color if she would like to add sausage curls or the top bun(s) types.

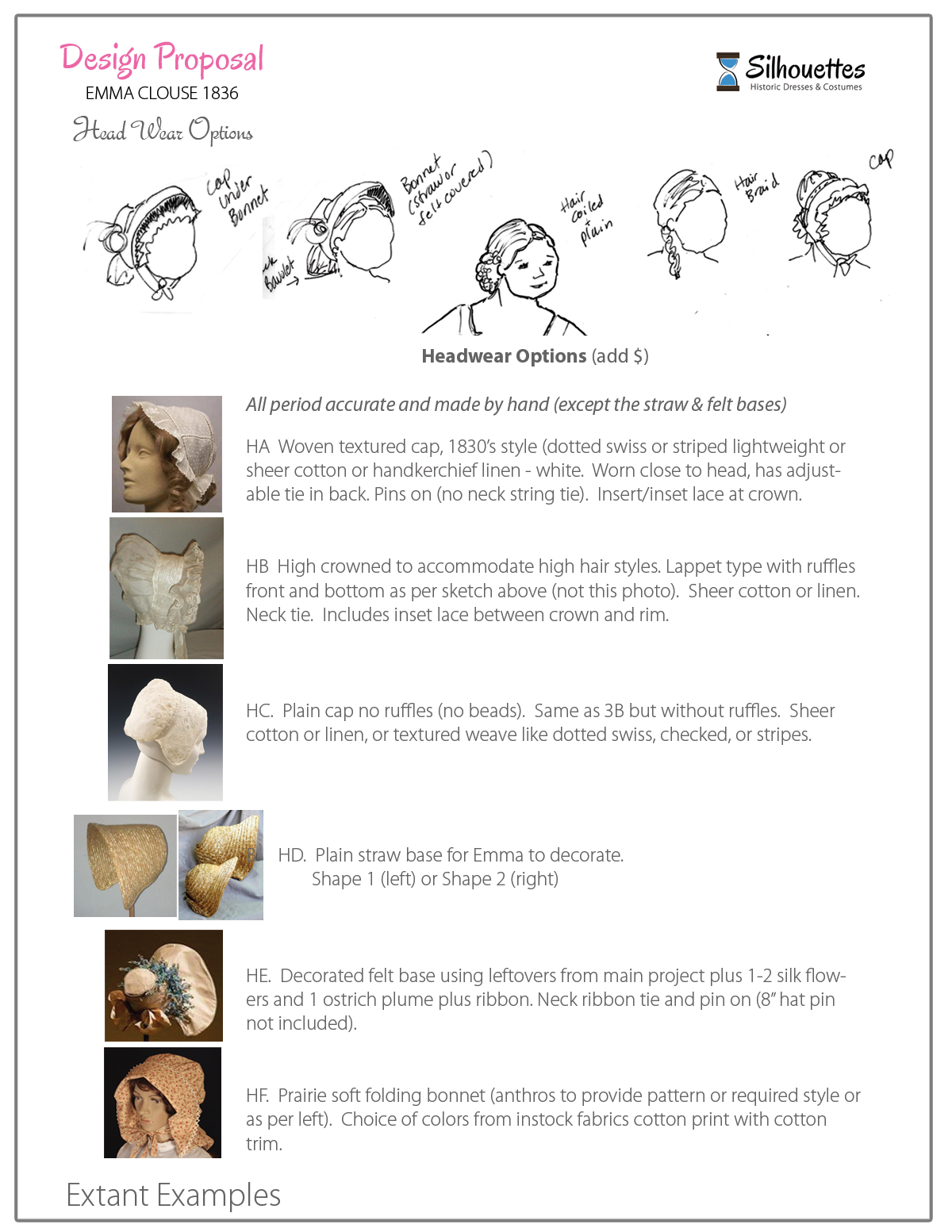

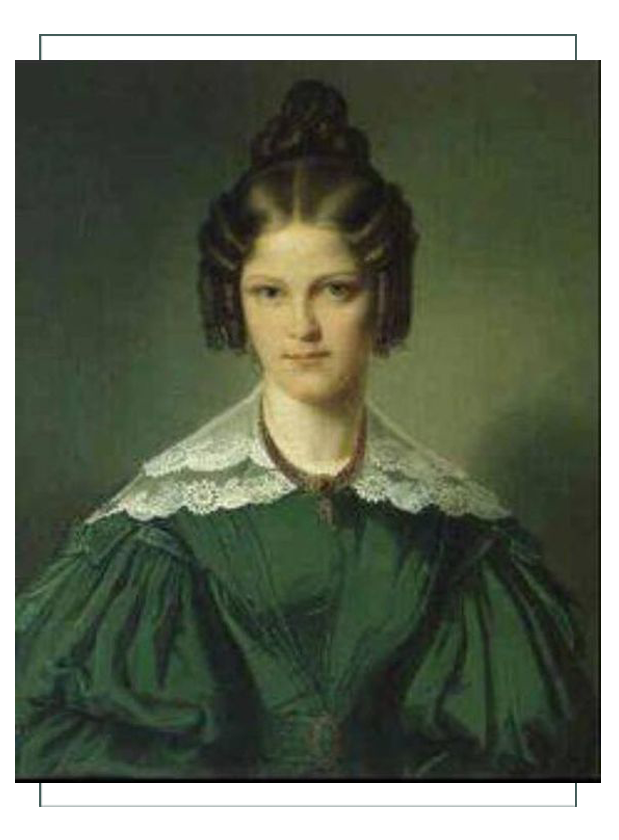

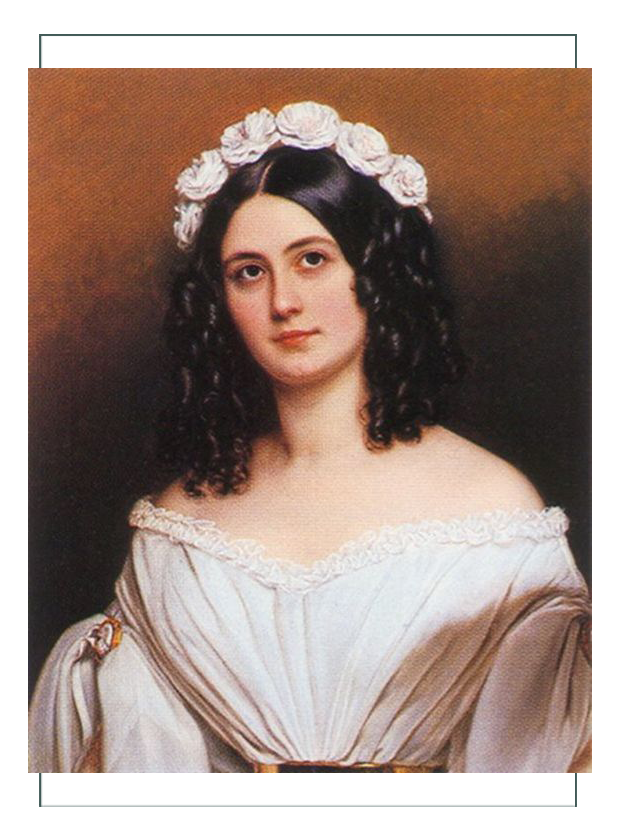

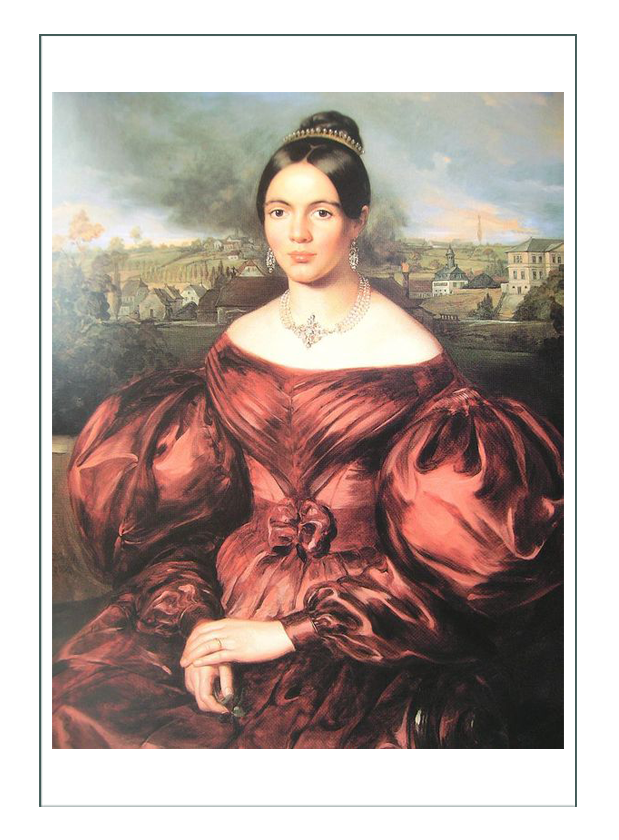

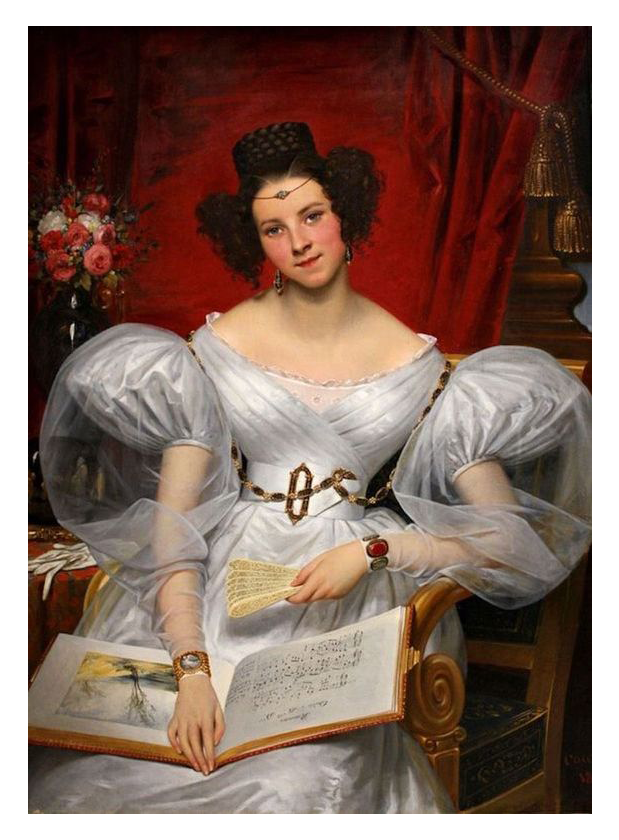

Below are some hair specific 1836 portraits we found that are not already on the “Fashion History” page, as we only touched in brief on footwear and headwear there. We will go a bit more in depth with those here to help Emma find what she needs from modern reproduction.

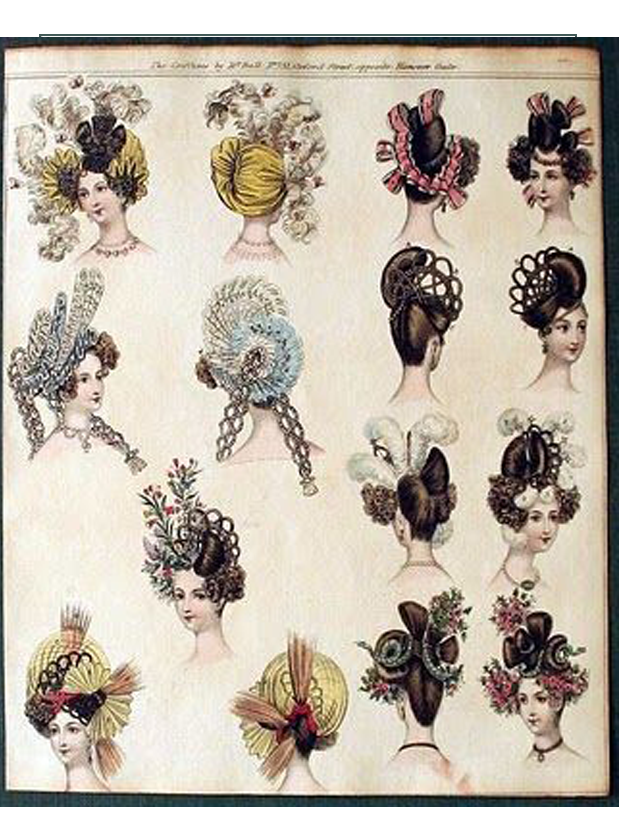

We thought we could find step by step “how to’s” for the 1830’s hair like we can for 1870-1910’s, but all we could find were illustrations and portraits (no step by step). First the extant (no cameras yet so everything was a portrait or sketch!):

Historic Examples

Modern Assitance

Modern links to BLOG Tutorials. They skirt before and after 1836 a bit, but have excellent hints and photos on “how to” with modern hair and minset:

Modern VLOG. She seems to be the only one right now doing this:

In looking for hair, we found ideas for the type of pelerine we’d like to build for this! Just love the “double lace” of the integrated collar. I think we can do this on an independent (not integrated into the dress; as a shawl) pelerine in white cotton with lace. What do you think Emma and anthropologist? Both have a section tucked into the bodice so it would stay out of the way and not bother while working.

Double layered lace Pelerine

Covered Bonnet – we have a felt base in stock!

Lappet Cap

This is a pattern which is commonly used. The first is what we’d like to build and is suggested in the proposal as a first choice to “add on”. It would be just like that.

If a bit less height or detail is desired, we can build it like either of the two below.only

A fabric found locally! (With some possible contrasting collars)

…more to come! We are waiting to know if Conner will open this year or not due to the closures across the country.

Click here to go to Emma’s Main Page with the Finished Project (next)

Click here to go to Emma’s Historical Context Page