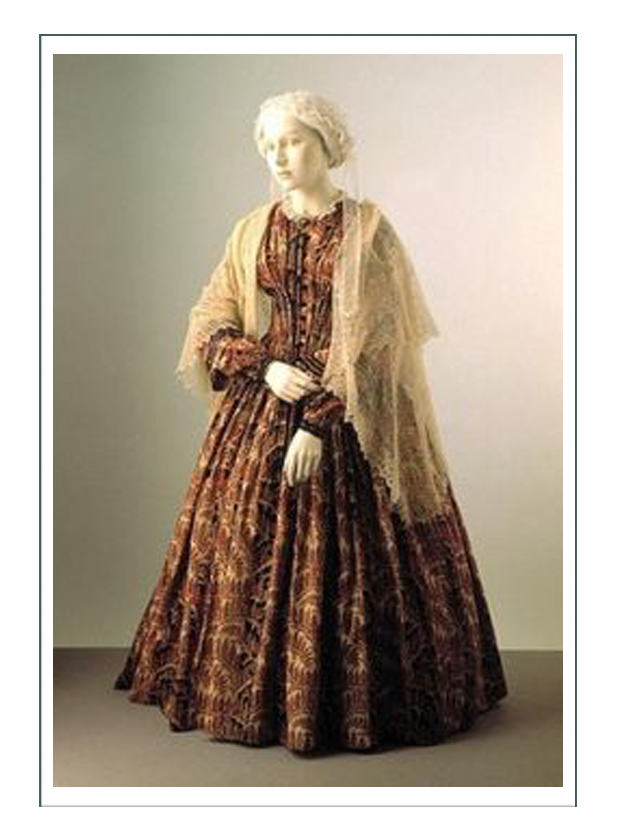

The “Romantic & Expansion Eras”

Regency to Victorian & Georgian to Jacksonian

1836 was a transitional time in the world between the conflicts of the past, and those that would come. It was a relatively peaceful time worldwide, where people escaped into literature and politics to literally become the characters of their imagination. The Romantic man of the 1830’s and 1840’s lived on a windswept hill top, wistfully looking over the city and brooding. The Romantic woman was demure and delicate; soft and submitting, while always keeping her man just an arm’s length away.

Because in the real world power was changing hands in the United States with a new presidency, and in England with the new reign of Queen Victoria, some of the old ideals crossed over with new ideas, innovations, and technology. The result was a mix of fashion concepts and shapes, so that there were many acceptable choices for women of all classes, ages, status, and geographical locations to begin to have choices and a bit of flexibility in what they wore.

We will look at the eras prior before, during, and after 1836 to determine which concepts would be best for Emma’s specific character depiction. First we go to what they were wearing in that misty fog on the hillside:

1824-1836

—— FASHION TRENDS ——

-

-

- While their mothers copied Greeks & Romans, the young women of the 1820’s looked to “Lady Guinevere”

- Lord Byron’s poetry wildly set the standard of good looks, lameness in men, & a flamboyant lifestyle that was the Romantic objective

- The ideal lady was fluttery & helpless, partly because she was again swathed in layers of clothes & a tight corset that made it hard to breathe

- Fashion of this Romantic era put emphasis on the “aesthetic” experience, or the emotion

- Being “picturesque”, or creating an overall image that evoked strong emotions was the objective

- Romantics were all about attitude; swooping about in capes with 2 day growths of beards, fine velvet jackets, & “Bohemian sensitivities”

- Gone was the freedom of the muslin dress; replaced by full skirted gowns with full leg o-mutton sleeves, & teeny tiny corseted waists

- Having started in about 1815, women were fully embracing the new look by the mid 1820’s

- They were probably getting too old to show so much skin, or tired of being cold all the time with the “little white gowns” of Regency, & glad to cover themselves up with the Romantic robes

- While reluctant to let go of all that classical charm of the past “Renaissance” era, the Romantic fad had led them back to works of art & literature about ancient societies

- Although they bathed more than the previous generation, they shunned cosmetics in favor of the delicate pallor brought on by drafty castles of their dreams

- If their skin was healthy, women blanched it with lead or vinegar to look sickly

- Bella donna was a deadly poison women put into their eyes to make them “luminescent”

- Daily sips of arsenic helped keep their skin pale

- Fashion became a mixture of “innocence & artifice”; some real hair & some fake; some real shape & some made by the trick of the eye

- The focus was clearly on femininity

- The problem with Romanticism was that it was VERY expensive

- Long flowing capes & Bella donna were not easy to come by

- Despite availability of mass produced items, they were not what was used to achieve the fashion of the day

- Expensive fabrics being used to get the romantic effects, plus the extra cosmetics & accessories, made the style impossible to maintain for most

- It was also highly impractical to wear in the field or factory

- The fashion went counter to women’s actual new mobility & place in society

- Only the high classes, nobility, & wealthy could continue the trend, & so it did not last long

- Class separation via fashion returned at this time

-

—— SPECIFIC FASHIONS ——

GOWNS

-

-

-

- The dress was no longer straight up & down.

- The fashionable feminine figure, with its sloping shoulders, rounded bust, narrow waist & full hips, was emphasized in various ways with the cut & trim of gowns

- Width at the shoulder & hip with a very tiny waist produced the 19th century’s first version of an hourglass silhouette

- From 1824 into the 1830’s, fashion was characterized by an emphasis on breadth, initially at the shoulder & later in the hips, in contrast to the narrower silhouettes that had predominated between 1800-1820

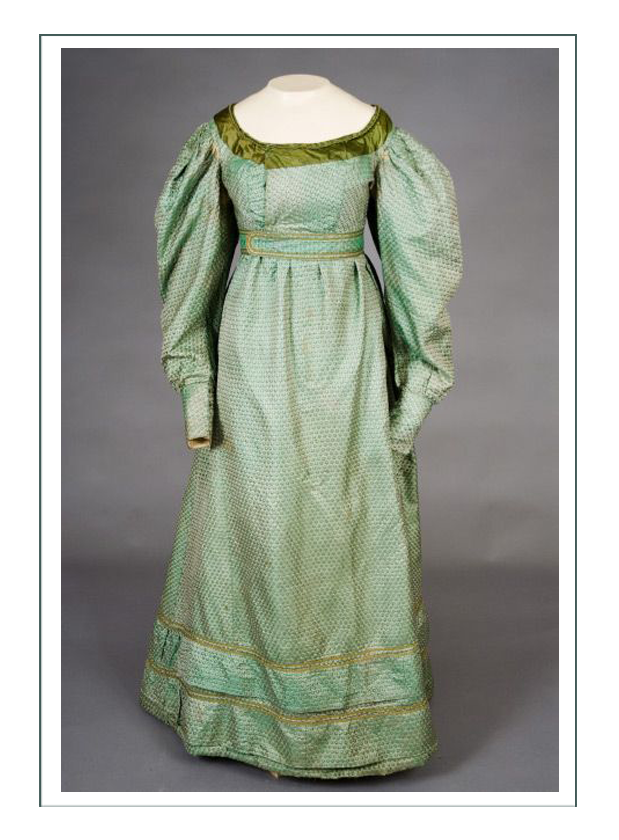

- Until about 1835, a wide belt with or without a buckle, like in the early 1820’s, was worn right under the bust to accentuate the small waist

- After 1825, the waist & midriff were unbelted, but cut close to the body. At this time, the bodice began to taper to a small point at the front waist

- Evening gowns had very wide necklines & short, puffed sleeves reaching to the elbow from a dropped shoulder

- Morning dresses generally had high necklines, & the visually broad shoulder width was created with tippets or wide collars that rested on the gigot sleeves

- Summer afternoon dresses might have wide, low necklines similar to evening gowns, but summer dresses had long sleeves

- In these, the skirt was pleated into the waistband of the bodice, & held out with starched petticoats of linen or cotton

- Chemisettes were popular. They were under-bodices of net or lace for low-necked gowns

-

-

BODICE & NECK

-

-

-

- The angular silhouette line which had been developing for some time reached its peak in the 1830’s, when the extension at the top of the dress & the extension at the base formed two triangles with the apexes meeting at the waist

- In the late 1830’s, when the sleeve collapsed, the silhouette became more rounded

- The center front of the bodice was sometimes slightly pointed, or worn with a Swiss belt which was pointed above & below the waist center front

- Bodices were cut as before, but were now always lined

- To create the wide shoulder silhouette, instead of being trimmed with applied decoration of the outer material, the outer material was draped over the bodice

- Pleated folds from the shoulders met at center front, or crossed over, or were draped to form a “Bertha” round top of the bodice

- A “Bertha” was when the drapery was cut on the cross grain, & then arranged on to the tight-fitting lining front & then back & seamed together on the shoulders & underarm

- This made the shoulder seams low at the back & the back side seams

- A modified “Betsy” or neck ruff was also popular

- “Mancherons” & wide collars gave further emphasis to shoulder width

-

-

SLEEVES

-

-

-

- At the start of the era, & keeping with the previous fashion style, sleeves were long & full; bound with cords spiraling down the arm

- The increase of sleeve size started with the puff sleeves at the shoulder becoming larger

- Then, in 1830, sleeves ballooned out from elbow to shoulder, & were fitted from elbow to wrist, replacing the demure cuffs of the 1810’s-20’s

- These were the elephant sleeves that would dominate this era, disappear quickly, & then return in 1895

- The giant sleeves were called “gigot” or “leg of mutton”. They had a triangular shape – very full at the top & fitting at the wrist

- By the end of the 1820’s the sleeve had become so extended it required extra support underneath. The enormous puffs & wings were padded, boned, or stiffened with down, stiffened interlining, & whalebones

- Shoulders visually disappeared until 1840, as huge, flat collars sloped from women’s necklines down to the fullest points of the giant sleeves

- For evening, the sleeves were wide & short & still often worn with a transparent over sleeve

- In 1836, having reached ultimate fullness, the sleeve style suddenly collapsed

-

-

SKIRTS

-

-

-

- By 1828 the skirt was shorter & at ankle length

- Around 1835, the fashionable skirt length for middle & upper class women’s clothes dropped from ankle to floor length

- The skirt expanded in circumference yet again since the last era

- The skirt was no longer gored, but cut from several widths of unshaped material

- Early in the era the fullness was arranged in pleats radiating from the center front & round the sides

- By the end of the 1830’s it was gathered all round

- Skirts were stiffened with buckram or horsehair to make them stand out, which was also used in sleeves & petticoats

-

-

UNDERGARMENTS

-

-

-

- Skirts were shaped by layers of starched petticoats that were stiffened with tucks & cording

- Petticoats worn were heavier, wider, & more numerous as time went on

- By 1825, the waist had reached the natural position

- A bustle (padded roll, not wire frame) or extra flounces held the fullness out to the back

- Undergarments of the era included down-filled sleeve plumpers, corset, chemise, & petticoat

- The chemise was knee-length with elbow length sleeves & made of linen

- Stays were now called corsets (after the French “corps” meaning body)

- A main distinction between stays & corsets was the invention of metal grommets & busks, which allowed extremely tight lacing

- Corsets had a center front busk & bones for center back lacing

- Becoming figure controllers, corsets would actually shape the body, rather than create a visual silhouette as was done with softer stays of the past

- Corsets allowed the extremely tight lacing that created a tiny waist, which was a particular vanity at this time

- Corsets compressed the waist & ran over the hips

- The gores/gussets made the bosoms round

- The fashionable corset now had gores to individually cup the breasts, & the dress bodice was styled to emphasize this shape

- At this time when the bodice fit all the way down to the waist, more seams were added & more bones, with sometimes a basque for the hips instead of gussets

- This basque style lasted until the late 1880’s

-

-

OUTERWEAR

-

-

-

- Huge sleeves, being difficult to stuff into the narrow sleeves of a pelisse, demanded a new type of garment for warmth

- The pelisse with its narrow shoulders was no longer practical, but it continued as a “pelisse-dress” rather than as a coat

- Short capes with longer front ends, called pelerines, became quite popular

- Full-length mantles (coats) were worn until about 1836

- Voluminous mantles of velvet or satin, with fur trim or fur linings in cold climates, were worn with the evening gown

- A mantlet or shawl-mantlet was a shaped garment like a cross between a shawl & a mantle, with points hanging down in front

- Shawls were still worn, as were tippets, but muffs became smaller

- Shawls were worn with short-sleeved evening gowns early in the decade, but they were not suited to the later wide gigot sleeves of the mid-1830s

- The burnous was a three-quarter length mantle with a hood, named after the similar garment of Arabia

- The paletot was knee-length, with three cape-collars and slits for the arms

- The pardessus was half or three-quarter length coat with a defined waist & sleeves

-

-

ACTIVEWEAR

-

-

-

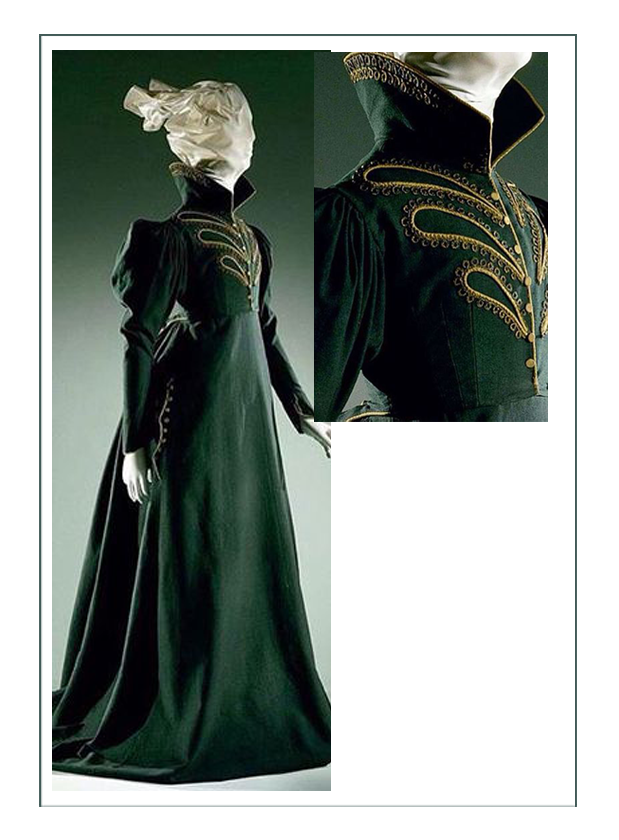

- Riding habits consisted of a high-necked, tight-waisted jacket with the fashionable dropped shoulder & huge gigot sleeves

- The jacket was worn over a tall-collared shirt or chemisette, with a long matching petticoat or skirt

- Tall top hats with veils were worn when riding

-

-

FABRIC & DECORATION

-

-

-

- Fabrics & colors were stronger now with purple, bright green, & blue being favorites

- Heavy fabrics such as plush, velvet, heavy woolens, brocade, & heavy silks were favorites year round throughout the era

- Cottons became firmer & there were many variations of cotton woven stripes & spot patterns

- Many of the woven striped or spotted fabrics were all white, but some spots & stripes were colored

- More silks, foulards, & satins, were being worn

- For evening crepe, net, or fine muslin was worn over a silk or satin slip (chemise)

- For evening, silks & gauzes were used alone or with the slip

- Embroidered white muslins were still worn, but now the embroidery was sometimes in colors, & the embroidery was heavier & coarser

- At the time of the large sleeve, draped bodice, & fuller skirt, there was less applied decoration & more use of patterned fabrics

- Favorite featured fabrics included printed cotton, chintz, challis (mixture of silk & wool), cashmere, & merino (light, short length wool)

- Trimmings & embroideries included beads & fringe

- Early in the era, dresses were still trimmed with applied decoration along the bottom of the skirt, but by the end decoration was placed on skirts at knee level

- Tucks, flounces, Van Dyked frills, trimmings bound with narrow piping, or trims embroidered in gold or silver, & ruching appeared round the bottom of the skirts

- On evening gowns, trim would be gauze caught with a narrow piping of satin or silk

-

-

JEWELRY

-

-

-

- In the early 1820’s, there was much less jewelry worn than in the past

- Jewelry consisted of brooches, bracelets, & crosses on chains around the neck

- Later, more jewelry was worn

- Later favorites were gold settings with semi-precious stones like turquoise, topaz, & amethyst

- There were brooches, earrings, & bracelets to match

- Bracelets were especially worn in the time around 1825

- The ferroniere of the previous era was especially popular. It was a jeweled headband worn across the forehead

-

-

HEADWEAR

-

-

-

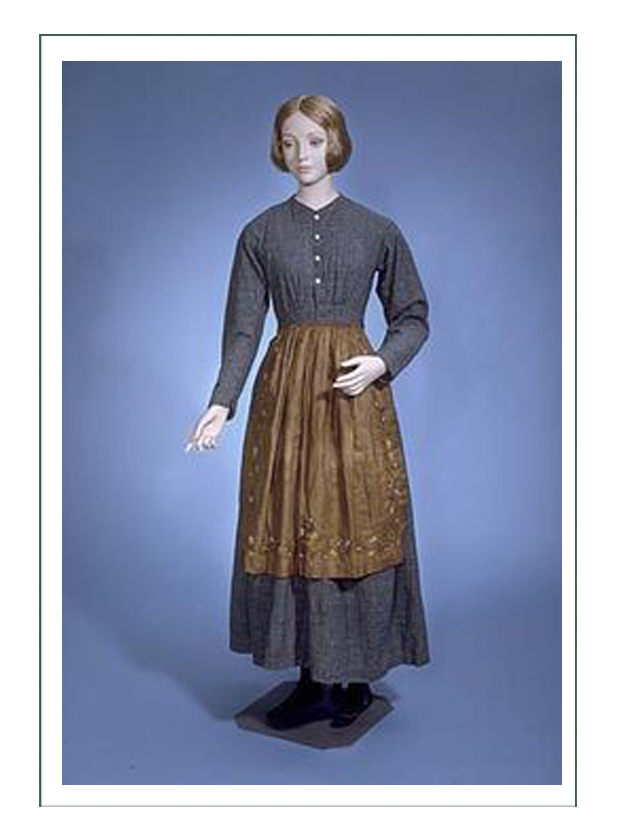

- Early 1830’s hair was parted in the center & dressed in elaborate curls, loops, & knots extending out to both sides & up from the crown of the head

- This became the “spaniels ears” hairstyle in the late 1830’s-40’s

- The classical chignon of the 1810’s became the whimsical sausage curl of the 20’s & 30’s

- Bonnets with wide semicircular brims framed the face for street wear. These were heavily decorated with trim, ribbons, & feathers

- Married women wore a linen or cotton cap for daywear. It was trimmed with lace, ribbon, & frills, & tied under the chin. The cap was worn alone indoors & under the bonnet for street wear

- Unmarried women wore bonnets or hair ornaments over their natural hair, either in the chignon or “spaniels ears” styles

- Hair ornaments including combs, ribbons, flowers, & jewels were worn for evening

- Berets & turbans were popular for evening too

-

-

FOOTWEAR

-

-

-

- Low, square-toed slippers were made of fabric or leather for daytime

- Evening slippers were square toed & covered with satin

- Low boots with stretchy inserts appeared in this decade

- Boots & shoes were buttoned until the invention of lacing grommets in the next era

-

-

ACCESSORIES

-

-

-

- When less trimmings were used on the garment, relatively more accessories were worn

- Add-ons included wide collars & fichu pelerines

- Pelerines were wide collars with long fichu ends that hung down in front & were caught in a belt made of silk

- Evening gowns were worn with short gloves

- Aprons of small & decorative, or larger practical use were worn

- Aprons were typically worn by domestic help, although women or girls might wear them around the house in private to protect clothing

-

-

—— REAL GARMENTS FROM THE ERA ——

—— (above) “Night Gown 1823” ——

—— (above) “Night Gown 1825” ——

—— (above)“Dressing Gown 1836” ——

—— (above)“Dressing Gown 1836” ——

—— (above) “Riding Habit 1825” ——

—— (above) “Redingote 1828” ——

—— (above) “Casual Day Dress 1826-29” ——

—— (above) “Every Day Cotton Gigot Sleeves 1830” ——

—— (above) “Formal Dress with Mancherons 1830” ——

—— (above) “Morning Dress with Bertha 1830” ——

—— (above) “Evening Gown Balloon Sleeves 1832-33” ——

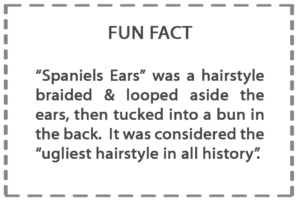

—— (above) “Pelisse 1835” ——

—— (above) “Silk Day Dress 1836” ——

—— (above) “Modified Bertha Collar 1836” ——

AND THEN

Coming down from that hill, our heroine would have found the world very much changed. Industrialization, innovation, and the shifting of alliances and agreements around the world between newly established countries and territories saw the expansion of government, land holdings, political power, and most importantly for our purposes, skirts, sleeves, and bodices.

1837-1851

—— FASHION & EVERYTHING IN THE WORLD GETS COMPLICATED——

DRESSMAKING

- Society in Europe & America was prospering

- Population was growing, especially in urban areas

- The idea of standardized clothes was still distasteful to many women, so dressmakers were still in vogue

- The sewing machine, now improved for mass production use, did not help with women’s clothing as much as with men’s, because women disliked uniformity

- Dressmakers even with sewing machines were hard pressed to keep up with demand for clothing

- It was more profitable for a dressmaker to hire out work to the elderly or young rather than use a factory

- Dressmakers had physical shops where they constructed, fit, & sold garments

- Clothes for upper classes were almost all still made by the visiting dressmaker, or customized by the large department stores

- In 1847, an American man with his mother started the successful Royal Worcester Corset Company which stayed in business until 1955

- Royal Worcester American corsets were the most popular & commonly purchased at this time

- Most corset manufacturers were creating a standardized corset & then fitting women into them

- RW designs reversed that thought process in that they were based on a natural line, & then adapted to the function or purpose; e.g. sports, evening gowns, breastfeeding, etc.

- Royal Worcester developed use of the couteil fabric that was functional & quality for a reasonable price, & would be used in corsets forward

READY-MADE

- There were huge shopping malls with department stores in Paris operating at their peak in the 1840’s & 1850’s including Galeries du Commerce et Industrie, Palace Bonne-Nouveau, & Grandes Halles

- Unlike today’s malls, these included inside custom dressmaking shops as well as ready-made items of all sorts from clothing to perfumes to household goods

- Ready-made applied mostly to cloaks, shawls, etc that a dressmaker would build during the “off season” in her large shop with apprentices

- Ready-made meant garments were pre-made in general pattern sizes, & then fit to the customer in the dressmaker or department store

- There was no such thing as “multiple” or “off the rack” until later in the decade

- Most ordinary women’s clothing was provided in stores. With buses, & railways booming by 1853, shoppers could easily come to the shopping district

- Drugstores were opened in every department store, selling cosmetics

- By the 1840’s every drugstore had a cosmetician who sold cosmetics with the goal of enhancing “naturalness” & fixing men’s black eyes

PRODUCTION, PATTERNS, & MARKETING

- Paper patterns made the home garment-making industry feasible, but the sewing machine was not yet refined for home use

- Paper patterns were used by dressmakers who switched from the draped design of previous eras to flat pattern design

- Designers through upcoming eras would go back & forth from draped to flat pattern design

- Because mass production meant cutting & then assembling 100’s of sleeves, or collars, or bodices instead of building the whole garment, flat pattern design was more efficient & less costly for factory production

- Lady’s fashion magazines like “Godey’s Lady’s Book” described the current fashion trends for all who could afford to buy the book with its hand-colored illustrations

- “Godey’s Lady’s Book” usually included patterns in standardized sizes based on the “proportionate principals”

- Wealthy women would give the patterns to their dressmaker to make

- Non-wealthy women would not be sewing their own “Godey’s” fashions anyway, but rather a lesser version of it, so lower classes obtained patterns through catalogs or department stores

- Fashion magazines were used almost exclusively by the wealthy & elite

- Photography became common in use by 1840 which allowed women to see what a fashion actually looked like

- Instead of word of mouth, use of old clothing, patterns, samples, or periodicals of past eras used to communicate design, women now most often chose their fashion from photographs

—— FASHION TRENDS ——

AMERICANS EMERGE

- Americans, other than a few railroad, shipping, & banking moguls, really did not have an elite class

- America was still made up of a huge middle class, with the standard of living highest in the world

- While heroes like Lincoln, Clay, & Webster set standards for men, women wanting to be stylish still followed European fashion as they had no American fashion leaders

- Not all American women adhered to European custom

- As with all eras in American fashion history, there were exceptions as women pioneered functional & locally made clothing

- This time period in particular, as the American West was first settled, established its own dress codes for women (discussed as a separate era)

- American fashion, specifically East Coast & Midwest as far as St. Louis, followed the edicts & was restricted by the same rules as Victoria’s Britain was

- The “Boston Lady” was a fashion ideal unique to America. She was a fictitious super-refined American woman that “did the continent” like a Londoner, dressed, spoke, & behaved like European aristocracy, & emulated the ways of the rich

THE RISE OF HAUTE COUTURE

- Early Victorian fashion is jokingly referred to as the time of “drooping ringlets & dragging skirts”

- The era might appear to be the same as the big & embellished previous Rococco, but despite general similarities of line & silhouette, the Early Victorian is actually almost “prudish” in comparison

- Early Victorian differs from the previous Roccoco because of all the strict rules & protocols of fashion dictated by Victoria & the rising designer, Charles Worth

- French “Haute Couture” & the term was invented by Charles Worth

- Worth was an English born designer who told French women what to wear

- What French women wore, was what everybody of European influence, including Americans, wore

- Worth’s concept was that each activity needed its own “costume”, a term he invented

- “Costume” was a complete fashionable ensemble designed & built for a specific function or event to accomplish a specific purpose such as projecting wealth, status, or community standing

- The result of Worth’s fashion was that anyone who could afford it needed to buy huge amounts of clothing

- “Haute Couture” meant there was a lot of dressing & undressing all day; usually requiring a servant or helper & so distinguishing the classes

- There were marked differences between which clothing was to be worn at which time of day

THE PAISLEY CRAZE

- A huge fashion trend that crossed “Haute Couture”, “Tailor Made”, ready-made, & mass produced fashions of the time were paisley shawls & piano shawls of paisley

- Paisley was a specific pattern of color & weave, based on Middle-eastern, Asian, & Eastern designs

- Paisley was used in high fashion for the elite & wealthy

- Paisley shawls also appealed to the mass market of the middle class

- Lower classes would embrace it later after it became in common use at lesser cost

- Paisley originally came from Edinburgh, Scotland in about 1845

- The first paisley shawls were of wool & silk

- Beautiful flimsy silk gauze examples, with bright clear colors were printed for evening wear for the middle & upper classes

- Heavier shawls of wool & silk with light colored centers were used for summer wear, & dark centers for winter

- Printers copied the designs of the woven examples, using wooden blocks & later blocks with the pattern lines inlaid with metal

- Shawls from Scotland were the height of fashion through the early 1800’s

- Norwich, Paisley, Glasgow & other towns printed shawls which were immensely popular

- Great Britain was able to reduce production costs through sub–division & specialization of labor of their mass production textile industry that Scotland did not have

- By 1850, Edinburgh Scottish paisley manufacturers could no longer compete with English Paisley & stopped producing shawls

- Norwich & France continued to produce very good quality examples forward to the present

- They were a favorite wedding present for all classes

- Passed through generations, paisleys were worn from infancy to old age

- They went out of fashion in the 1870’s when they became associated with the elderly

AN ATTEMPT AT BLOOMERS

- A third key trend in this era that never took off were Amelia Bloomer’s “bloomers”;

- “Bloomers” were pantaloons worn under a loose fitting blouse-like tunic intended to take women out of corsets while still keeping her modestly covered

- Bloomers were an attempt to simplify the growing complexity of fashion & its understructures, & it failed miserably until 50 years later when the advent of the bicycle demanded women wear something with a split leg

—— SPECIFIC FASHIONS ——

CRINOLINE SILHOUETTE

- By the 1850’s the term “crinoline” applied to the silhouette as well as the item

- A crinoline was an undergarment structure which further expanded & stiffened the starched petticoat of the previous era

- It widened the bottom of the profile tremendously, creating a wide shouldered, tiny-waisted, & hugely exaggerated hourglass shape of a bell

- “Belle” (“beautiful” in French) was a term appropriately applied to women of the American south who wore the skirts & structures

- Leading up to 1850, a crinoline was a stiffened or structured petticoat designed to hold out a woman’s skirt

- The first crinolines were made of horsehair (“crin”), cotton, or linen

- “Crinoline” also meant the hoop skirts that replaced the crinolines in the 1850’s & 1860’s

- NOTE: In form & function, hoop skirts were very much like 16th &17th century farthingales & 18th century panniers in that they were made of stiff structural materials combined with the horsehair & fabric to hold the skirts into specific (large) silhouettes

- Crinolines were worn by women of every social standing & class, from royalty to factory workers

- Their use was subject to media scrutiny & criticism, & there were many caricatures, jokes, & satires about them in magazines like “Punch” at the time

- Crinolines could be hazardous, as they were extremely flammable

- Other crinoline hazards included hoops getting caught in machinery, carriage wheels, gusts of wind, or other obstacles

- Crinolines & the later hoops allowed skirts to spread wider than ever, up to 6 yards (18′) in diameter at their peak in size & depth in 1857

- The steel-hooped cage crinoline was patented in 1856

- Steel-hooped cages were distributed by agents, intensely marketed, & mass produced in huge quantities by factories in Europe & the US

- Whalebone, cane, gutta-percha, & inflatable caoutchouc (natural rubber) were used for hoops, although steel was the most popular

- By 1860, the hoops began to reduce in size a bit

- The smaller crinolette & the bustle had largely replaced the crinoline by the early 1870’s

BODICES

- The separate blouse & skirt was introduced in this timeframe

- Lines shifted from the vertical to the horizontal on top as well as on the bottom of the silhouette, assisted by shorter, wider bodices

- Women’s 1840’s day dresses had boned bodices with dropped shoulders

- Dresses had a fan-front (gathered) bodice that formed a point below the waist

- Dresses had piping at the waistline, armscye, neckline & shoulder seams.

- Dresses had much less ornamentation than the previous era

- Bodices were worn off the shoulder

- They featured a rigidly boned elongated shape with a waist that formed a perfect point in the front

- Shoulders were extended below their natural line

- Generally necklines were worn high during the day & wide in the evening

SLEEVES

- A new triangular, cone-shaped silhouette emerged featuring new pagoda sleeves

- Huge sleeves had suddenly collapsed in 1836

- The new form-fitting sleeves were sometimes so tight that tiny pleats were inserted at the elbow to aid in movement

- Sleeves in the 1840’s were short & tight with either puff decorations of lace trimming

SKIRTS

- In about 1852, skirts become even fuller than the previous era when they had widened to a “bell shape”

- It was still a “bell shape”, but a much larger “bell” formed by cartridge pleating

- Horizontal flounces or tucks were added to the base skirt to give it width & volume

- Trimmings of tucks & pleats were used to emphasized the new line

- Skirt hems lowered to the floor

- Starting from the mid 1850’s until the end of the century, women’s skirts & understructures continued to get more drapery, a more layers, more stiffening, & more complexity

- As the era progressed towards 1857, the skirt became very domed in silhouette, requiring yet more petticoats to achieve the desired shape

- The trend to get more & more ornate continued into the 1860’s

FABRICS & TRIMS

- There were many more fringes, beads, bugles, & bows with ruchings, loops, & swirls added as time progressed

- Solid, colored fabrics were more in tune with the new solemnity of the era

- Colors shifted to darker tones

- Prints & patterns gradually were introduced & became the norm

- The huge expanses of fabric were crying out for visual interest which large plaids & border prints provided

- Fabrics were the same stiff textured cloth as previous eras in winter or cool climates

- Light cottons were typical in summer

- Bright printed & woven fabrics were popular

- Daytime colors were brown, rust, gray, & green & included Scottish plaids, following the lead of Victoria who loved them & wore bright authentic plaids in silk to social functions

- Pale pastels were for evening

- The designs of the main dress were repeated in matching pelerines

UNDERGARMENTS

PETTICOATS

- Multiple layered petticoats & crinolines provided the fullness of the desired silhouette over the very tightly laced corset

- Numerous petticoats were worn

- The more the crionoline was worn, the less petticoats were worn

- Some stiffening was used to support the skirts, but with the advent of the crinoline, only 1-2 petticoats became necessary

- 2 petticoats were preferred for modestly, as the crinoline did not count as it might sway or blow up revealing the naked woman beneath, or at least an ankle or foot

- Petticoats were decorated with “broderie anglaise” which was tucking & lace

CORSETS

- The corset returned in full force with intent to mold the body into a proscribed shape, rather than to trick the eye

- Waists became smaller & even more tightly laced than in previous eras

- Strong metal grommets made the tight lacing possible

- Previous eras had hand sewn eyelets, which would not have taken the stress

- Center backs & fronts of the corset had additional metal “lacing bones” to take the stress of lacing off the fabric

- New innovations in innovative “busk” closures for front & back made the entire garment much stronger & durable

- Design was flexible with many construction methods available

- By the 1850’s, there were 4 basic corset shapes, with variations by intended activity

- There were corsets for sports, riding, maternity, evening, & travel based on the 4 main concepts

- The 4 corsets all had in common a design which produced a wide & very round bosom with a tiny waist

- No emphasis was made on the hips except to make the corset long enough so that it sat comfortably on the waistline

- Gussets that had been present since the 1790’s in corsets disappeared, to be replaced by seaming

- It was the new shaping of seams that would have a major effect on corsets until the end of the century

- In general, all corsets of the time had colored outer fabrics & a white lining

- Sateen & jean “couteil” fabric was produced in America specifically for corsetry

- Silks, satins, & batistes for decorative outer layers were made in Italy

- Nettings were used for summer corsets

HEADGEAR

- Hair was neatly pulled back into a snood. Snoods were lace or linen coverings over most of the head or at least the back of the head, such as food service workers wear now

- Snoods were worn in the evening too, but they were ornamented with pearls or other decorations for formal occasions

- Hats were now small & worn tipped forward, as introduced by Eugenie, Empress of France

ACCESSORIES & ODDITIES

- Women wore a little rouge, powder, & eyebrow pencil

- Less proper ladies wore pearl & violet powders & rouge

- Women wore false ears complete with earrings

- Parasols & pouch bags with wooden handles were carried by every woman

- Gloves were worn constantly for each & every situation except meals when they were discreetly placed next to the napkin ring

- Gloves were made of lace or silk net; often worked with gold threads for the upper classes

- Early Victorian jewelry included a ribbon around the forehead with a jewel in the center (“ferronniere”)

—— ACTUAL GARMENTS FROM ERA ——

—— (above) “Basic Gown 1838” ——

—— (above) “Dress and Mantle 1840” ——

—— (above) “Cotton Day Dress 1840” ——

—— (above) “Striped Silk Visiting Gown 1841” ——

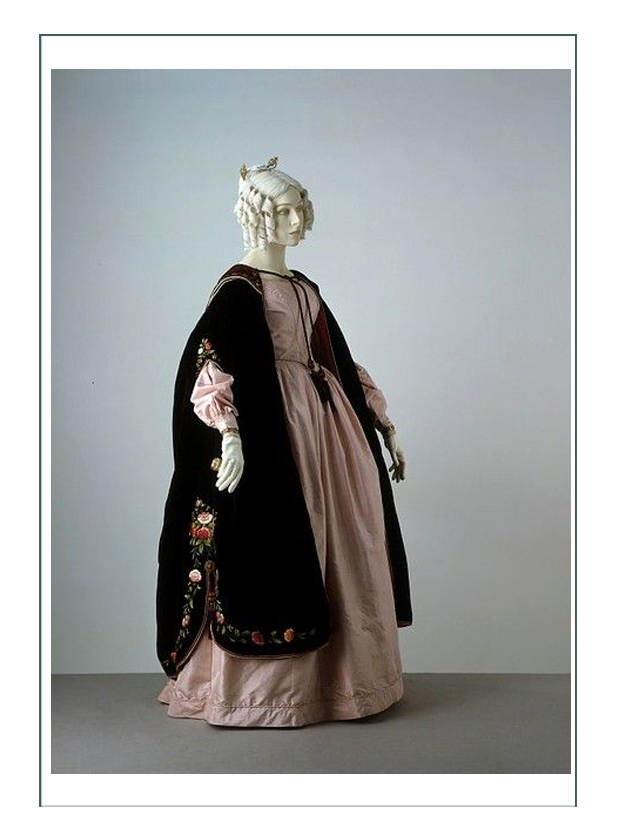

—— (above) “Hired Help 1845” ——

—— (above) “Visiting Dress 1848” ——

—— (above) “Mantle 1850” ——

—— (above) “Mantle 1850” ——

—— (above) “American Made Cloak 1850” ——

—— (above) “American Made Cloak 1850” ——

—— (above) “Queen Victoria’s Ball Gown 1851” ——

—— (above) “Winter Day Dress 1851” ——

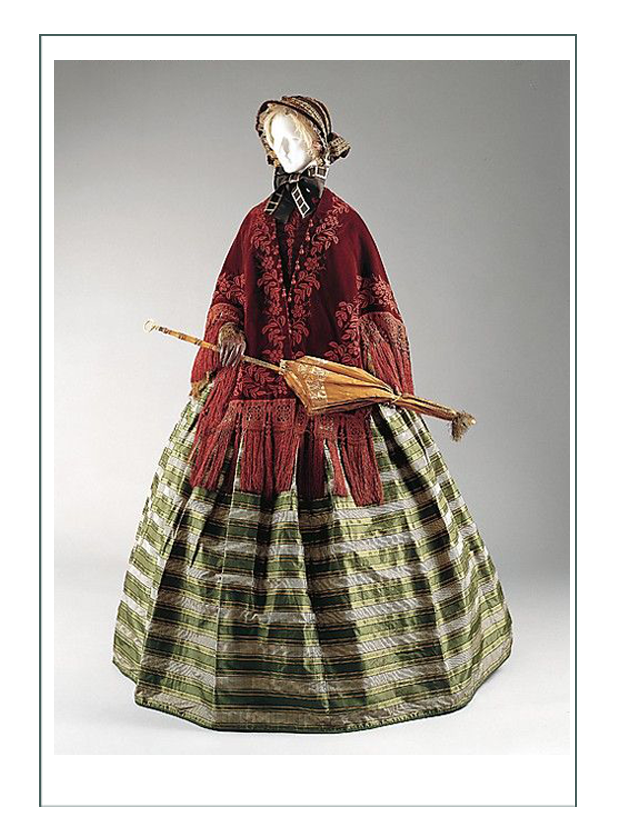

—— (above) “Traveling Ensemble 1851-53” ——

A lot of information. Now what to do?

The answer to how does 1836 fit in to this 1824-1851 era, being smack in the middle of it all is more questions:

- Who are you and what are you doing?

- Where are you?

- What do you know?

- What can you afford?

- What do you like?

In other words, the Silhouette’s basic premise applies:

However, that is cheating, so we will summarize and pull out the key elements for design from the (basically two) eras we have just defined. We will find the commonalties between the two, and what would most likely (based on extant garments, portraits, and first hand sources such as diaries and journals, what is most likely to have been worn in specifically 1836. We will also lean rather heavily on the Prairie Living History farm anthropologists who have the power to say “yay” or “nay” to our design and materials choices. Let’s continue the discussion on the design development page (next).

Expectations of the Boss

Following is an excerpt from the Living History site website where Emma will be working. It is written by the woman previously in charge of costuming docents there. From this we can determine what it is they are expecting of Emma. Quickly we see the demand for accurate color, print, fabric, design, and bonnet. We read between the lines they do not expect but would prefer docents to wear a corset, and do expect them to wear modern underpanties instead of the split drawer that was gaining popularity at the time. We will need to decide if drawers or more petticoats are preferred.

Author: (name provided on request. This is copyrighted material, but we are protecting Emma’s location and identity so will not disclose), Former Director of Programs

Clothing the family of the 1830s was an important task, and most of the work was the responsibility of the women.

Every stitch of the sewing had to be done by hand; Elias Howe didn’t even invent the sewing machine until 1846, and Isaac Singer’s version didn’t come about until 1850.

Of course, ordinary people didn’t have the large wardrobes we expect today. They made do with one outfit for every day, one for Sunday best, and perhaps one other, or parts of another, for seasonal change. Even wealthy people didn’t necessarily have lots of clothes, although their money allowed them to purchase ready-made items from the storekeeper, or to hire custom sewing done outside the household, or by a temporary live-in seamstress.

Where a family lived determined to a great extent where and how they obtained their clothing. City and town dwellers usually purchased the fabrics, if not the entire garments, from specialty or general stores. People in rural or remote areas were more likely to undertake the whole process themselves. Still, it was possible for nearly anyone to order nearly anything to be sent to them from a merchant in the next town, or even from a merchant oceans away. It just took a very long time to arrive.

There were a great variety of fabrics available for making clothes in the 1830s. They were all “natural” fabrics; wool and linen were most common, with cotton and silk were scarcer and more expensive. Hundreds of weaves and patterns were available.

A rich selection of colors existed even before synthetic dyes were developed in the late 1850s. These early colors were made from plant parts-leaves, stems and blossoms of woods and meadow flowers; roots, barks, nut hulls and tree galls; berries, fruits, pits and skins; mosses, lichens, and fungi and non-plants, such as insects and shellfish.

Many dye sources were imported from tropical areas, and were sold in general stores. They were widely available to both home dyers and professional dyers. The professional dyers sometimes supplied services even to home spinners and weavers. Really, every combination of home and outside professional endeavor went into the providing of fibers, fabrics, and garments in the 1830s.

Often the whole family helped to produce the cloth used for their clothing, especially if the family were rural or frontier.

Sheep were fed and sheared by the men of the household. Wool cleaning and carding were done by young children. Spinning yarn on the high wheel, dyeing it over the cooking fire, and loom weaving of “homespun” fabric were done by the unmarried daughters and aunts. Mothers, sisters and grannies sewed up trousers, coats and dresses; all the women and young boys and girls knit caps, mittens and stockings. Several sheep could provide enough wool for the needs of the average family each year.

When linen was used, the fiber came from the flax plant, which was grown as a field crop.

A quarter acre of flax plants was enough to clothe the largest family. After harvest, the plants were rotted in water to break down the cellulose in the stalks. Then they were “broken” then scraped or “scutched” with a knife, and “hackled” or across several boards covered with sharp metal teeth to separate and align the fibers for spinning. These processes were difficult work, and required strength and determination. When the fibers were all prepared, they were spun on a low wheel, and then loom woven into linen shirting or sheeting, or table linens. Since the only capital investment in linen fabric was for flax seeds, with all the labor being supplied by the family, it was cheap to produce, and was the cloth most used by poorer families, or those on the frontier. It was also the cheapest fabric to buy.

Cotton cloth was readily available, but it was imported from England, or at least New England, and so usually required cash to own.

Cotton was grown in India, where there was plenty of cheap labor to perform the backbreaking field work and then the tedious picking out of the cotton seeds from the harvested cotton bolls.

Spinning, dyeing and weaving of the cotton ~ also hand-done very cheaply in India, or the harvested cotton was shipped to England where the newly developing power machinery could turn it into spun threads and then into woven cloth. England developed a monopoly on cotton and sold it to other countries at great profit.

The early American colonies were forbidden to produce their own cotton fabrics, and were forced to purchase them from English merchants.

Later, after the American Revolution, the growing of cotton and the manufacture of cotton cloth encouraged both the slave population of the southern states and the industrialization of the New England states. But, because cotton cloth production was not a family industry, it was expensive to buy. People who could afford to buy cotton cloth found a nice variety of gaily printed patterns. Cotton fabrics were a favorite gift for men to take home from their travels.

Silk, then as now, was for wealthier people to own. Most silk was imported from China and India. It was relatively scarce and relatively expensive.

Though silkworm culture was experimented with throughout the early days of America, the climates and vegetation were not suitable, and the huge amounts of hand labor required were too expensive for silk production to become established in America.

What kinds of clothing did the families of one hundred fifty years ago make with the fabrics available to them?

For men, everyday clothing consisted of a linen pullover shirt, made with full sleeves, deep buttoned cuffs, a generous collar, and very long tails to tuck into the trousers.

Underwear was not worn, so the tails helped protect the wearer from the scratchy wool of the trousers. The pants had straight, fairly slim legs, and a flap which buttoned to the waistband in front covered pockets on either side of the opening. The width of the flap determined whether the trousers were known as “broadfalls” or “narrowfalls.”

A wrapped tie, called a cravat, covered the throat. A vest was always worn, either single or double breasted, with shawl collar, or without any collar, whether or not a coat went over it. It helped to hide the suspenders, or galluses, which held up the trousers. Belts were not used by men at that time.

Several styles of coats were worn, depending on age, occupation and social status. There were tail coats, which were waist length in front, but had thigh-length tails in back. A “frock” coat had a thigh-length narrow or moderately full skirt all around. A “round-about” was cropped off at the waist. Coats were both single and double breasted, and the collars were cut so that the vest showed beneath them. Coats were always fully lined. They were made of wool, linen, or cotton, depending on the owner’s finances and the dictates of the weather.

There were overcoats, some with shoulder capes, great capes and capotes with attached hood for cold weather. Many farmers wore heavy wool shirts called waumases, which were said to be warmer and easier to work in than coats. These were especially popular in New England.

The Herald In The Country (1853) William Sidney, Museums At Stony Brook

Rustic Dance After a Sleigh Ride – 1830 – William Sidney, Mount Museum of Fine Arts Boston

Shoes were leather boots of various heights for day wear, and slipper-like dancing shoes were available for gentlemen who needed them. Portraits of the time period show some gentlemen wearing dainty shoes with pointy toes, high arches and elevated heels. Stockings were usually handknit of wool or linen, but machine-knit fine stockings were also available from New England mills through local merchants.

Several hat styles were available – round crowned, wide-brimmed fur felts, higher-crowned “toppers” of beaver fur, with slight flares to the taps, high-crowned, wide-brimmed woven or plaited straw for summer. Silk hats were increasingly popular after 1830, as beaver pelts became scarcer and more expensive.

Gentlemen of financial means often gave expression to their wealth by choosing finer fabrics as well as a larger and more varied wardrobe. They may have had cotton shirts as well as linen, perhaps with ruffles at neck and sleeve. Their vests might have been silk damask or embroidered silk satin, rather than wool or linen. Their boots were of fine leather.

Only wealthier men owned enough shirts to be able to set one or more aside as “night shirts “; they simply wore to bed the one they had been wearing during the day, and then continued to wear it the next day.

Wool knit stocking caps were sometimes worn on the head at night, particularly in coldest winter; bedrooms, especially if they were separate from the primary room, were usually unheated at night.

‘Bargaining for a Horse’ (c. 1835) by William Sidney Mount – Image from New York Historical Society

Women in the 1830s wore full or ankle length one-piece dresses of wool, silk or cotton.

Simple day dresses for house and farm work opened down the front to the waist, (the better to serve the needs of the nursing infant.) They were pinned closed, or fastened with hooks and eyes closely set. The sleeves were usually long; the fashion of the 1830s had most of the fullness very high early in the decade, lower in the arm as the ’30s progressed. Skirts were very full, either pleated or gathered onto the bodice. The waist was slightly higher than natural waistline. Necklines were generally modest, although lower cut was considered appropriate for festive evening or party wear. A fichu, modesty ruffle, or lace was usually worn on lower-cut necklines.

Day dresses had several removable collars and capelets which were worn in layers over the shoulders. These “pelerines” often matched the fabric of the dresses, or were of sheer white linen or cotton. Sometimes they were elaborately embroidered. Day dresses were apt to be made of serviceable dark color – especially winter garments.

Laundering clothing was difficult, and not done casually; it was a full production.

Aprons were always worn to protect the skirt during work, and often dressy aprons were worn whenever a woman was at home, even in the evenings. The aprons were usually linen, though some were made from sturdy fabrics like jean.

Dressy dresses usually opened down the back, and were also closed with hooks and eyes. For summer and party wear, sleeves were shorter. They were still very full, however. All bodice seams were “piped”, with narrow cording of matching or contrasting fabric. Hems were deep and faced with heavier fabric to protect them from wear. Bodices were always lined.

Under these garments, women wore shifts, or chemises, of linen or cotton. They were simply made, with short sleeves and necklines which could be gathered up on a drawstring. There was no waistline, but the shift was gathered by the dress worn over it. This piece served as the sole piece of “underwear”.

Over the shift a woman wore her “stays.” or corsets. These were constructed of heavy cotton, intricately seamed and boned with whalebone to achieve the appropriate body line. In the 1830s this was a high bust, small waist, but not exaggeratedly so, and the waist slightly high.

The construction of the dresses was planned with the stays in mind; the seaming of the garments and the definition afforded by the stays were complementary. Every woman was expected to wear stays, summer and winter. Only the woman without any social pretensions whatsoever would consider herself dressed without stays. No underdrawers were usually worn, however, women did wear at least three petticoats at all times, more when it was cold, or the dress required it. They were usually cotton or linen.

Country women often wore a simple work boot, when they needed to be shod. More fashionable city women wore light weight kid leather slippers, black for every day, but pastel colored to match their party frocks. Some of the shoes had ribbon ties. During this period, the heels were very low. As the dresses were ankle length, the stocking showed. Women’s stockings were knit of wool, cotton and linen. Sometimes the stockings were decorated with knit designs along the sides, either in colored threads, or as a pattern stitch. The hose were about knee high, and were either black or white.

The finer the gauge of the yarn, the dressier the stockings were.

There was great interest in fashion, and the nuances of the changing fashions from London, Paris and the eastern cities.

Monthly magazines detailed all the latest modes and materials. Sketches and minute descriptions were written so that the most remote lady could be aware of up-to-the-minute fashion, if she wanted to reflect it in her dress.

Some few ladies of means and ambition no doubt did this; most women were content to be generally current. They remade older dresses to show more modern trends, altering sleeves, waistline heights, hems, replacing pleats with gathers or vice-versa, changing ribbons and trim, trying new pelerines and collars. The cloth had been too dearly obtained to abandon, and too many of their scarce hours had gone into the original stitching to toss aside.

It was not uncommon for a dress to be remodeled a half dozen times, and finally to be entirely re-cut and made into a garment for a child.

Some fashion forms endured for many decades.

The cloak or great cape was an example of this. It was the usual outer cover of a woman’s dress for a couple of hundred years, with changes coming very slowly. As long as skirts were floor length, the cape was very practical. Some had extra shoulder capes for added warmth and rain protection.

The usual fabric was wool, but silk capes for dress were often made. These were usually lined with wool, as even a summer evening could be cool. Some of the capes had attached hoods. Others were intended to be worn with bonnets.

Women kept their heads modestly covered most of the time. They wore “day caps” of fine linen or cotton, with ruffles around the face, and chin ties. These were even worn under the cape hood, or under the summer straw bonnet or winter quilted bonnet. Ladies of fashion wore elaborately decorated bonnets when they left home: flowers, feathers, lace, ribbons, ruchings and ruffles abounded. For sleeping, many women wore night shifts or night gowns, usually full and straight falling, with long, full sleeves and high neck, of cotton or linen, and a night cap.

Children’s clothes were similar for boys and girls until about the age of six.

Both wore “dresses” of cotton or wool around the house. Occasionally, a boy’s dress would be worn over “drawers” to match, which showed beneath the dress. Little girls often wore pantalettes peeking beneath their dresses. The usual child’s dress was long or short sleeved to suit the season, with slim sleeves, round or boat-shaped neck and the waist was lightly fitted with a set-in belt. Preferred fabrics were linen and cotton, for ease of care.

By the 1830s, corsets for young children had gone out of style, though there were a few die-hards who insisted on keeping children in stays from infancy, so they would develop straight backs. Most physicians, however, and magazine consultants, argued against this as being too confining, and in fact inhibiting of a strong body. Free exercise of the little muscles was better. For this reason, they advised against swaddling infants, as had long been the custom. Infant garments were long gowns, and babies always wore caps.

As children matured into pre-teen and teen years, their clothing more and more resembled that of adults. Their duties were adult; there was no “teen culture” and no particular fad clothing for youth. Often they wore hand-me-down clothing of their parents, unless the family was very wealthy. It was usual for clothing to be passed down from child to child, even shoes.

A much greater proportion of a family’s time, especially the mother’s, was spent on producing and caring for clothing than is usual now, even though constant laundering of garments was not done. And, a greater proportion of the family income was spent on clothes in the 1830s than now.

From here we select key elements and discuss the design and possibilities with Emma on the Design Development page.

Click here to go to Emma’s Design Development Page (next)

Click here to go to Emma’s Main Page with the Finished Project

Click here to go to Emma’s Historical Context Page

Click here to go to the top of this page