The 1805 Setting – Time & Place in the World

In consideration for the play’s setting, is that of a high middle class family. Taking place at a time when the new United States had 20 years to have recovered from its War of Independence from England, and just on the verge of industrial revolution, a key merchant or business man such as the character’s father would have access to the latest materials, techniques, and technologies.

America in 1820 would lead the world in cotton production and textile manufacturing; in fact America would lead much of the world in manufacturing and use of natural resources. Having also resolved relationships with England and the rest of Europe, they would be doing a lively business of trade world-wide; predominantly as exporters.

The United States in 1800 had the highest standard of living of any place in the world – including England and France. England and France were at war; this was the era of Napoleon’s seize for power, and his continual conflicts. Conflict between the two powers, and introduction of other European countries into the world trade “loops”, reduced American dependency on information and resources from those places.

Instead, the United States became the supplier; the innovator – particularly of technology that would lead to everything from zippers to steam locomotives in the next decades. Of particular note for this character would be the lively merchant shipping trade; especially to US controlled territories or those previously held by England such as the West Indies.

This reduction of dependency and laud to European ideas, and independence puts this time on the line between the US as a colony, and the US as a world power. The key players in that process would be that same middle class – the plantation owners, farmers, arms manufacturers, textiles, and the many other industries that the US was beginning to dominate.

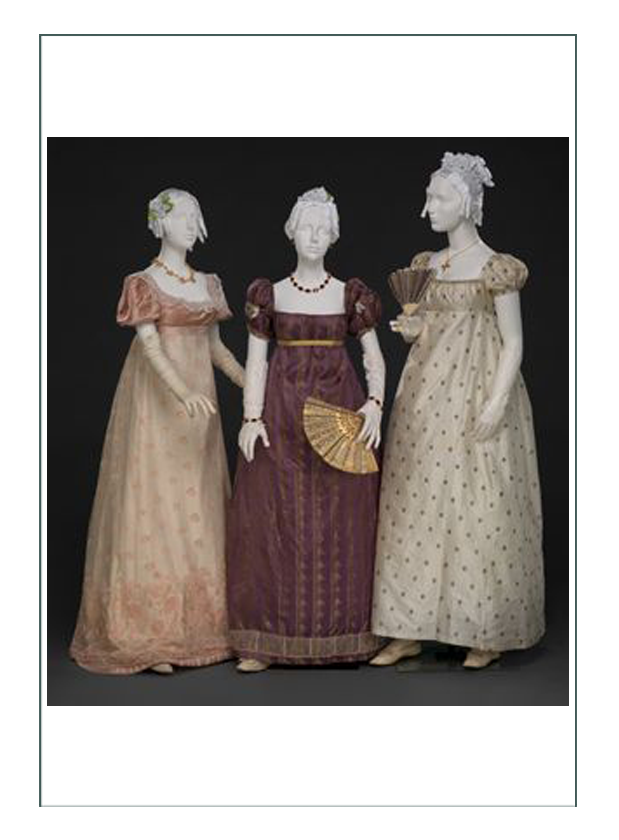

At the same time, with European powers cut off from each other and worldwide ideas and goods, plus being short of money due to the cost of war, meant previous influences, such as with fashion, would be stagnant for a time, allowing again the US to prevail in the output or sale and creation of innovation to the world, instead of from the world.

Eastern Cities – Grand Estates & Plantations – A type of “Suburbia”

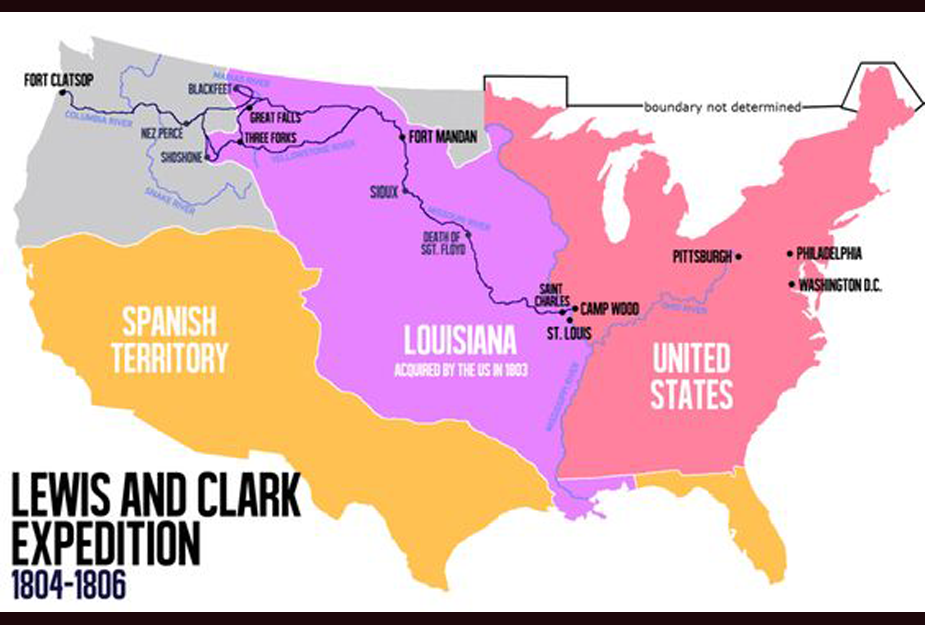

In 1800, the Wild West was only explored by a handful of mountain men and venturers. The Lewis and Clark Expedition was well under way, but most Americans other than indigenous tribes lived on the east coast, and along the political centers of Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, and Connecticut, with the rural plantations of the Carolinas and Virginias on the southeast.

Very little in the way of goods or ideas would come eastward from the western regions for at least another 30 years when the trappers and explorers opened trails into the otherwise pristine Native American lands.

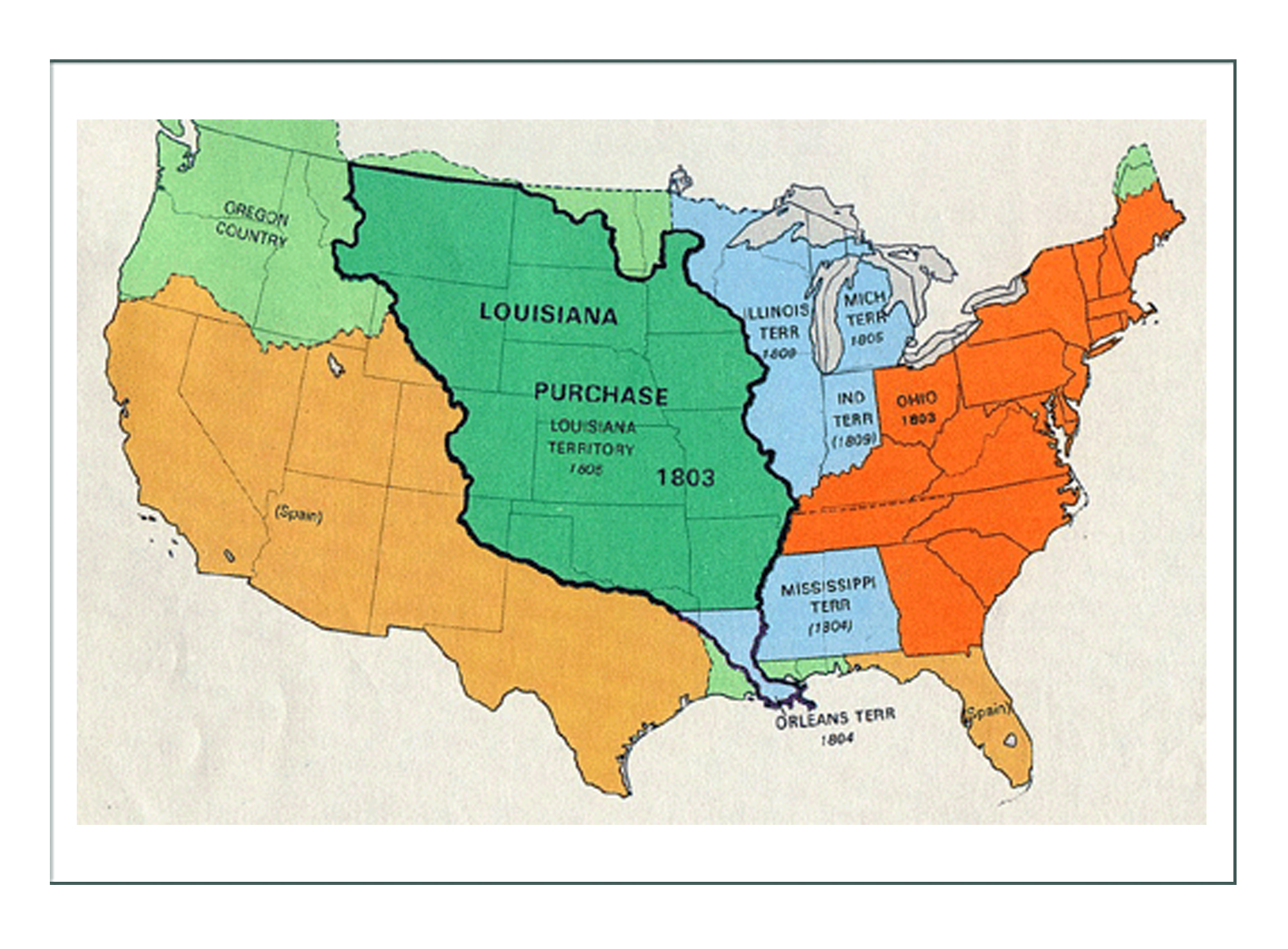

America was therefore still based on the original 13 colonies – those being centered in government and industry towards the north (which would later become Union in the War between the States) – predominantly Pennsylvania, New York, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Massachusetts where the larger settlements (cities) were, and the south – the Virginias and Carolinas with Williamsburg at the “center”. Further westward or inland, and even south in what would become Florida, Missouri, Texas, Louisiana, etc. or west as far as Illinois and Kentucky was still considered dangerous and unsettled wilderness.

Most Americans, unless Native Americans, lived on individual or family farms, plantations, or properties having their various industries (mills and such based on the power of water or horse until the advent of the steam engine) – or – near or in the larger towns and settlements. The densely populated urban centers with child or woman labor such as was seen in Europe would not be seen in America for many years. American society was still very agrarian based, and trade and industry would be agrarian based for some time yet.

Lay of the Land – The physical place

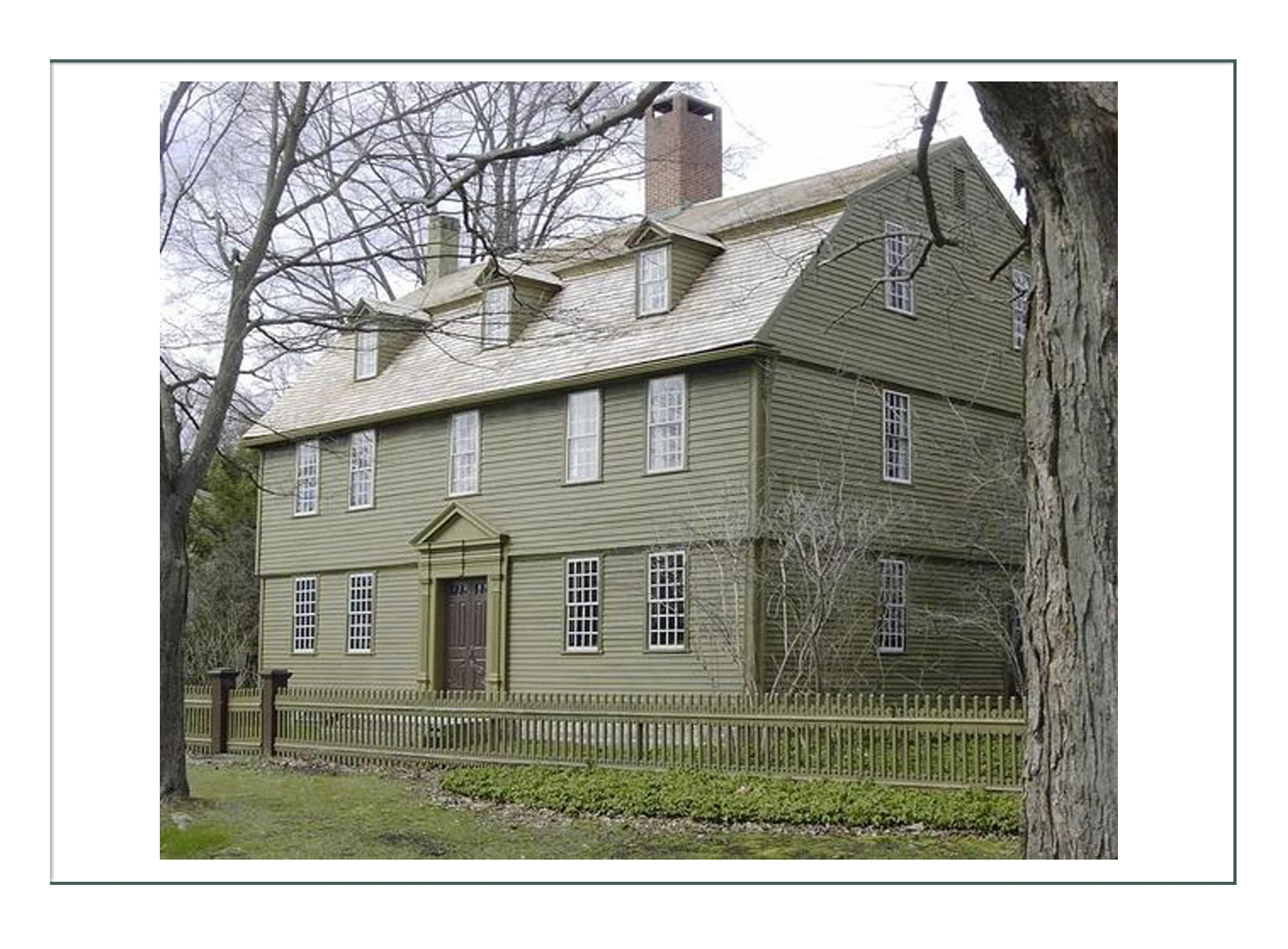

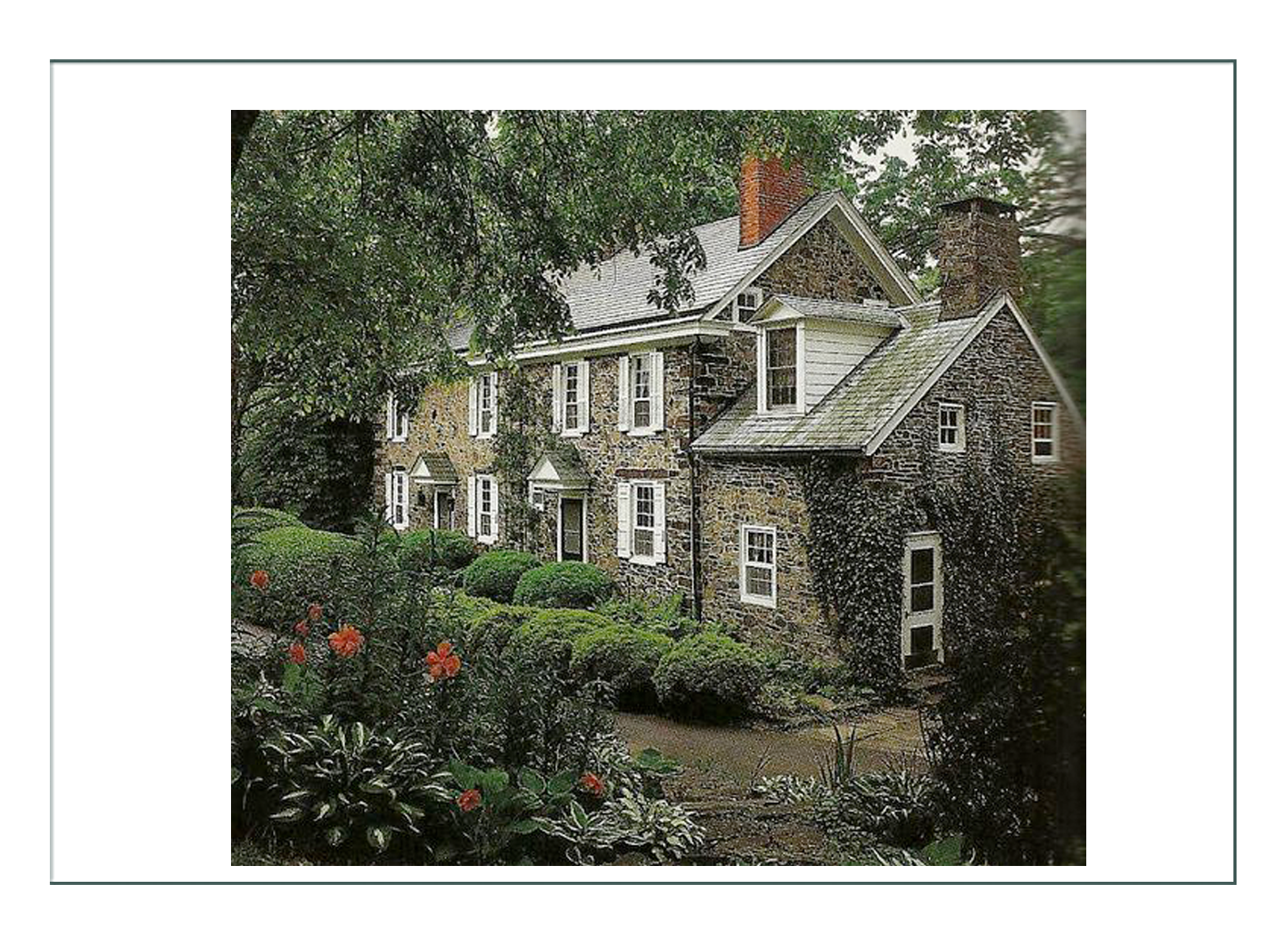

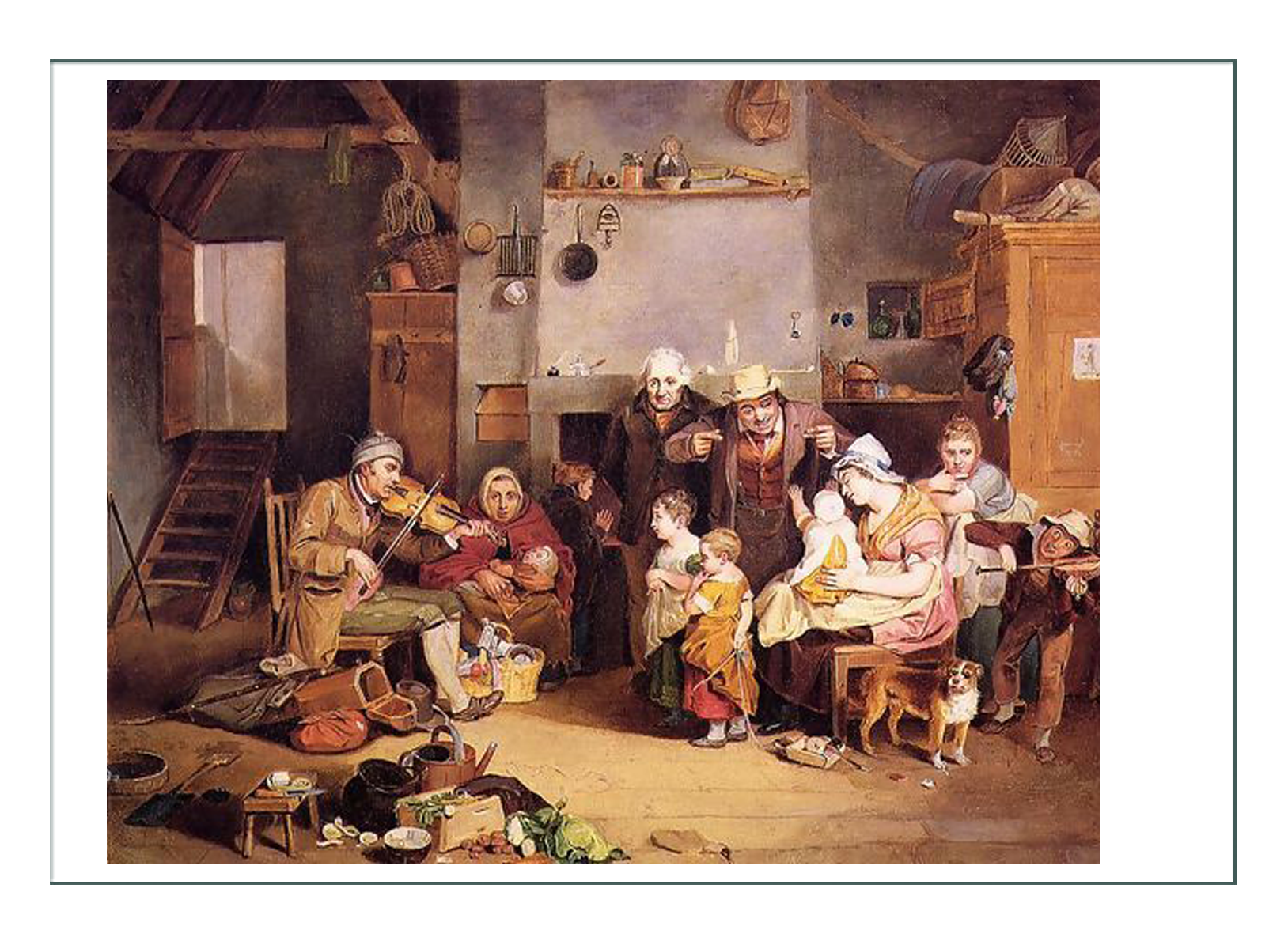

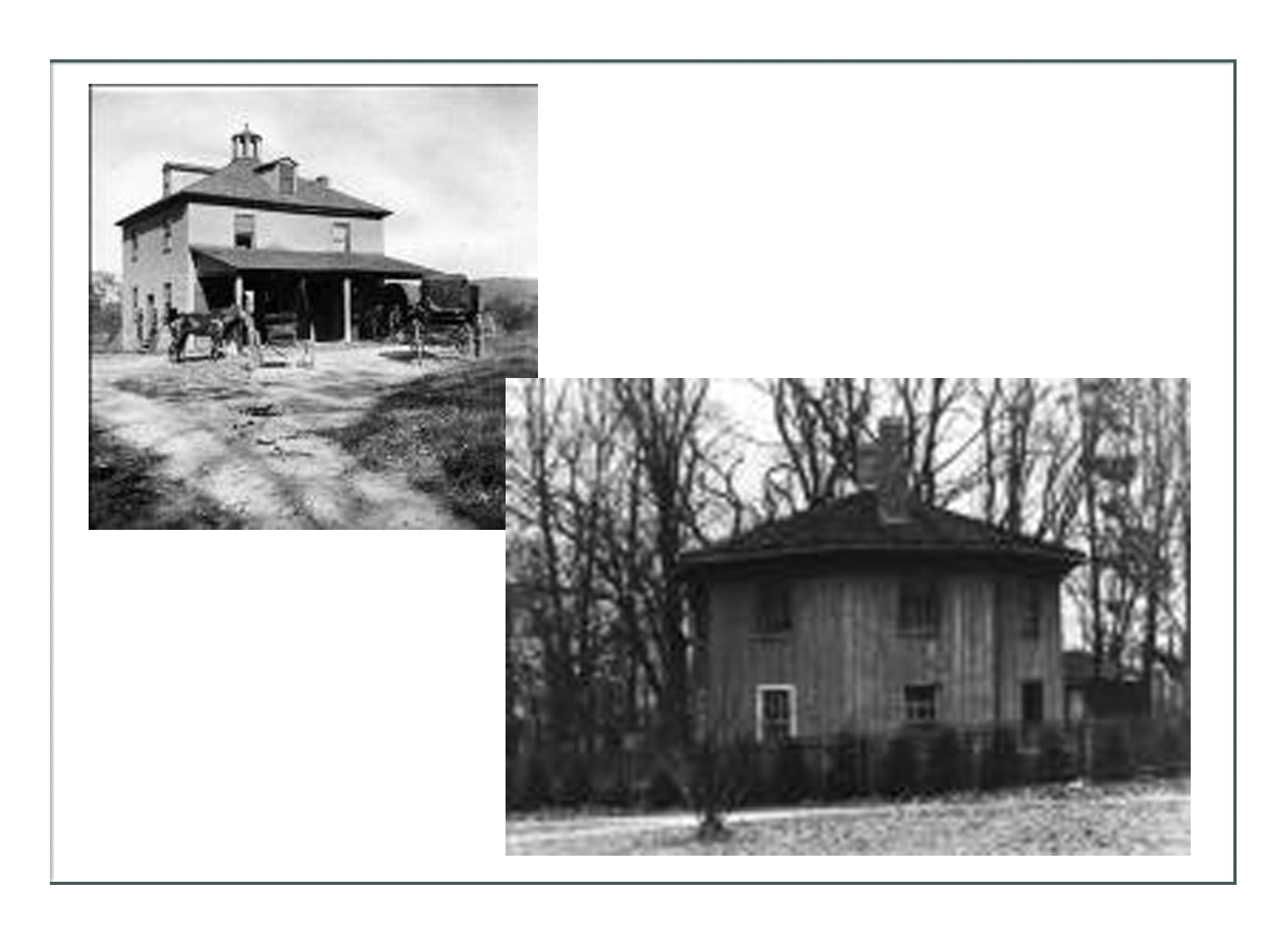

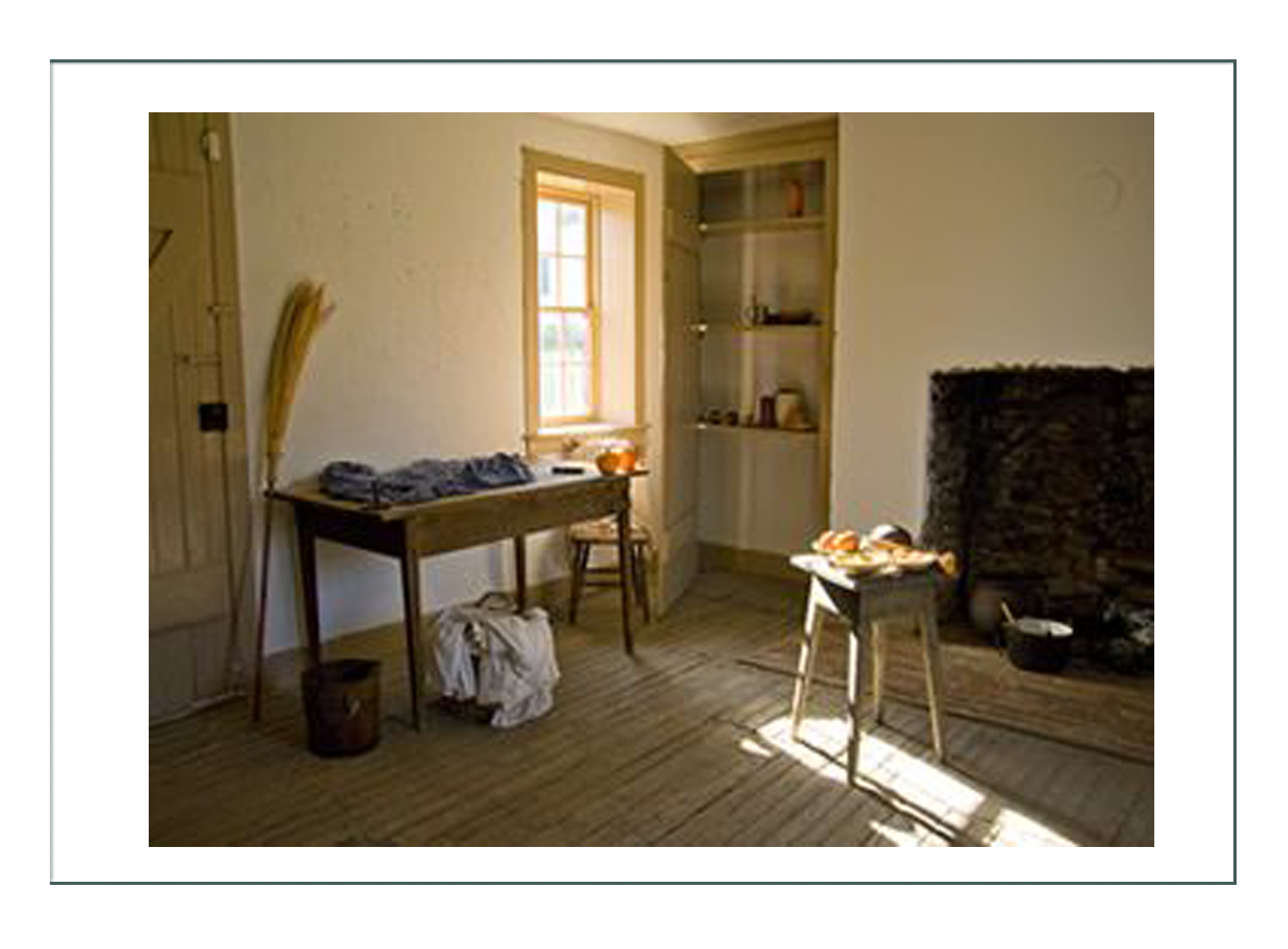

A typical 1800 homestead would consist of house, outbuildings including those for the animals of work, land, and especially in the case of southern plantations, entire slavery based communities.

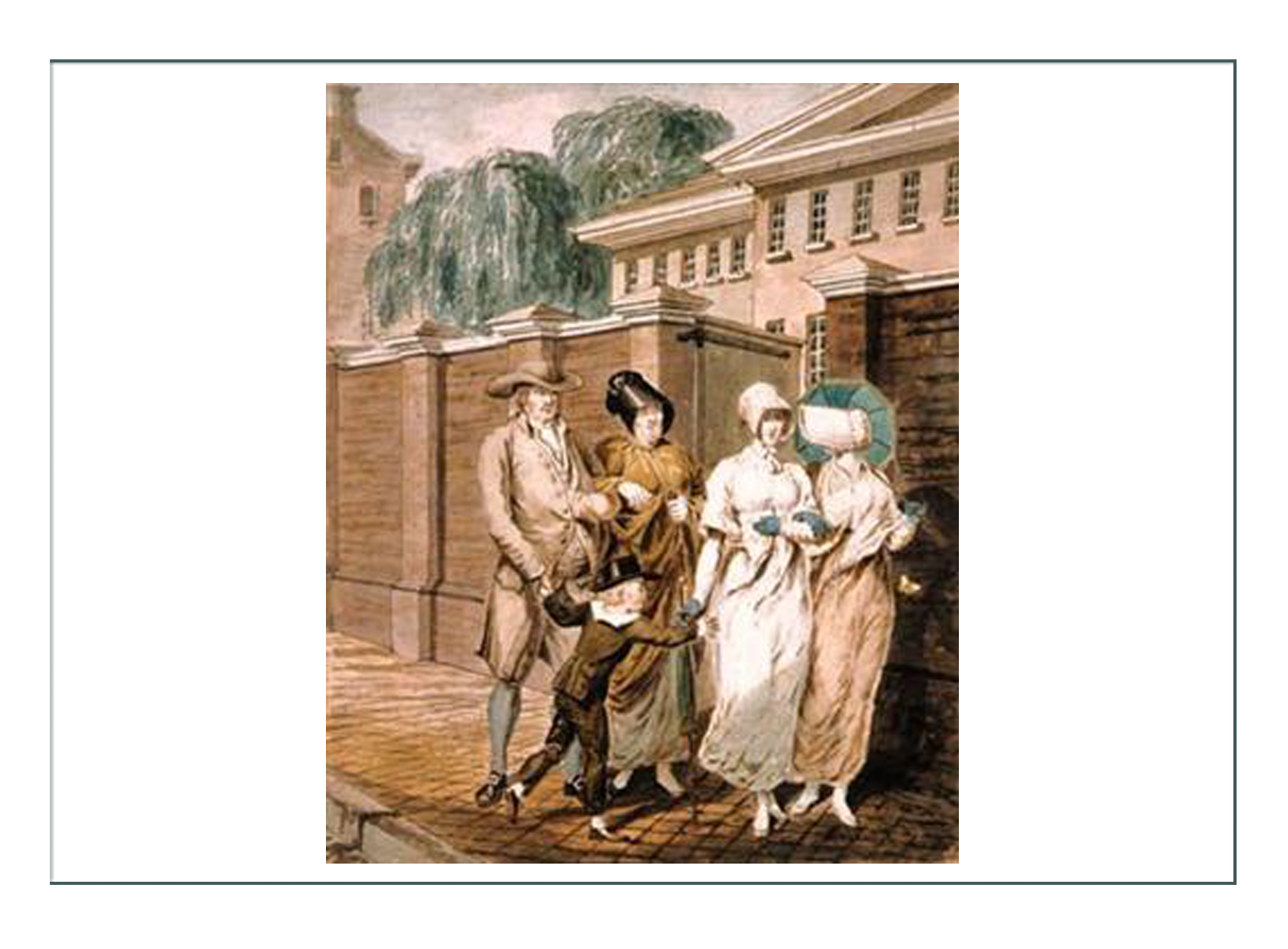

A merchant’s daughter might live in town in the family’s townhouse, which would be provided since the family home or farm would be some miles from the city. As in England, the purpose of this would be to ensure family members could be active in society while the man of the house conducted business. The farm or plantation would be at these times left in the hands of a manager.

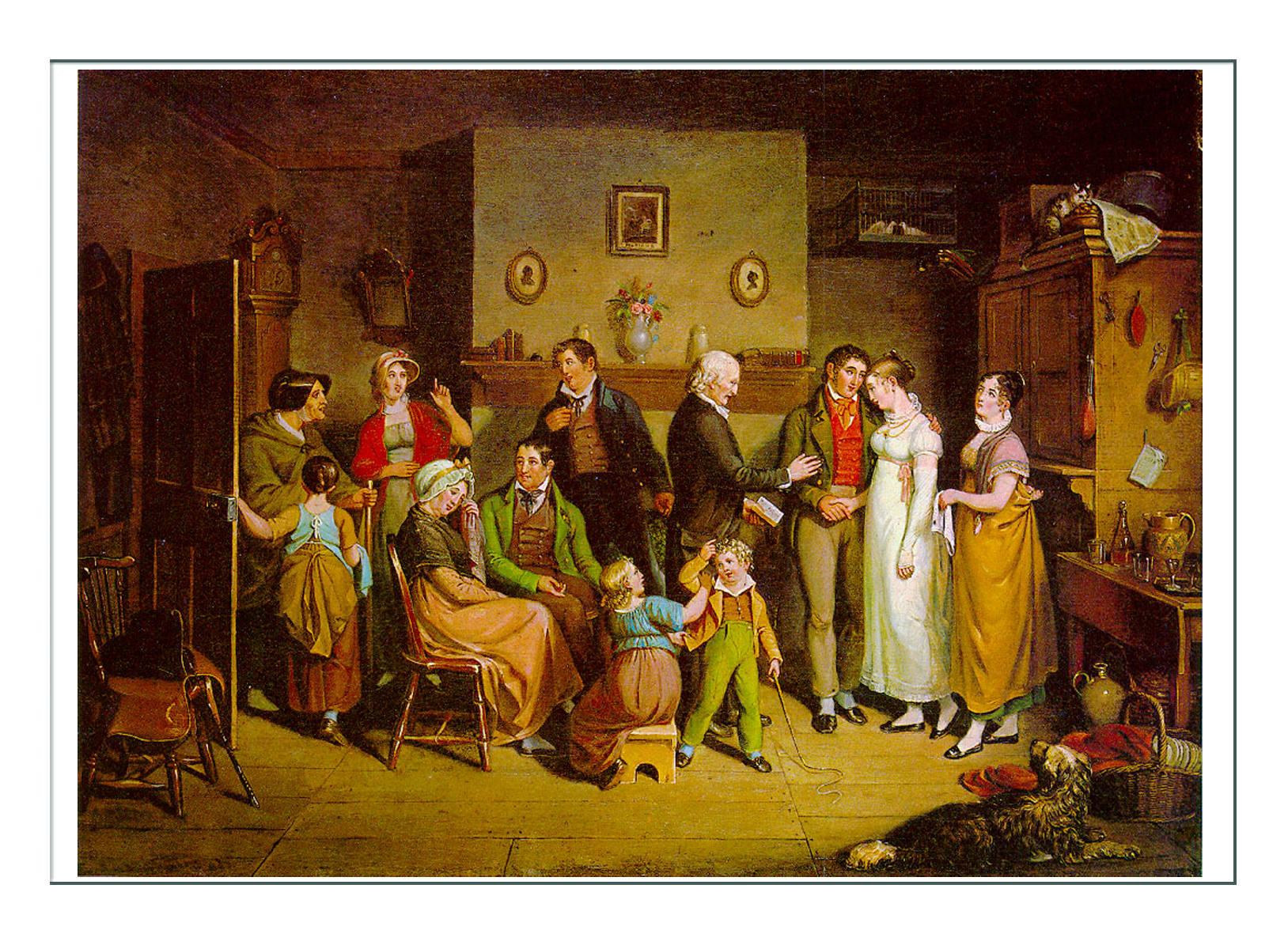

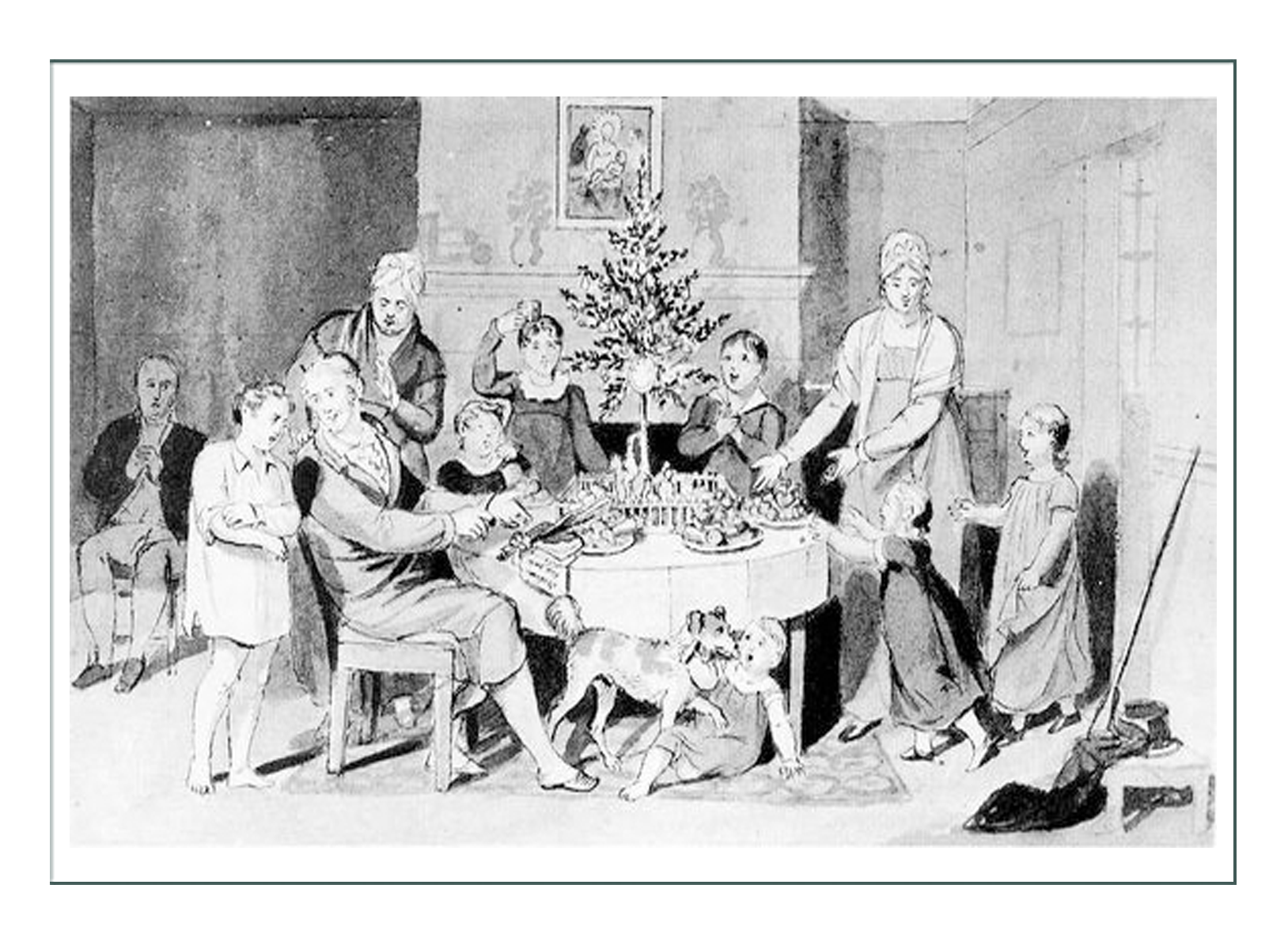

Because travel was by horse and cart/wagon/buggy, it was days in between towns or cities, so social occasions meant travelers might drop in and stay for weeks at a time, not just for a cup of tea. For this reason the house in town or country would need to accommodate overnight guests.

Families were typically very large, with the average being 12 children per household, so homes for middle class, merchant, traders, or industrialists as well as farmers or plantation owners were larger than our modern 1-2 child families would need. Add to that cooking was done over a fire, and the many intentional designs to accommodate weather, situation, and activities such as summer kitchens, outdoor “necessaries”, and accessory buildings to house or stable the equippage of guests distinguished homes of the era from those further inland (such as log or stone cabins) and the city row or townhouse of density.

It is this situation the character would find herself in; an eastern large and comfortable home which could house many siblings, but still require her to share her private spaces. There would be places for father to conduct business, for mother to entertain, and behind the scenes of it all, multiple work and storage spaces to prepare and serve food, and to manufacture those goods necessary to run whatever the business at hand as well as the household and grounds itself.

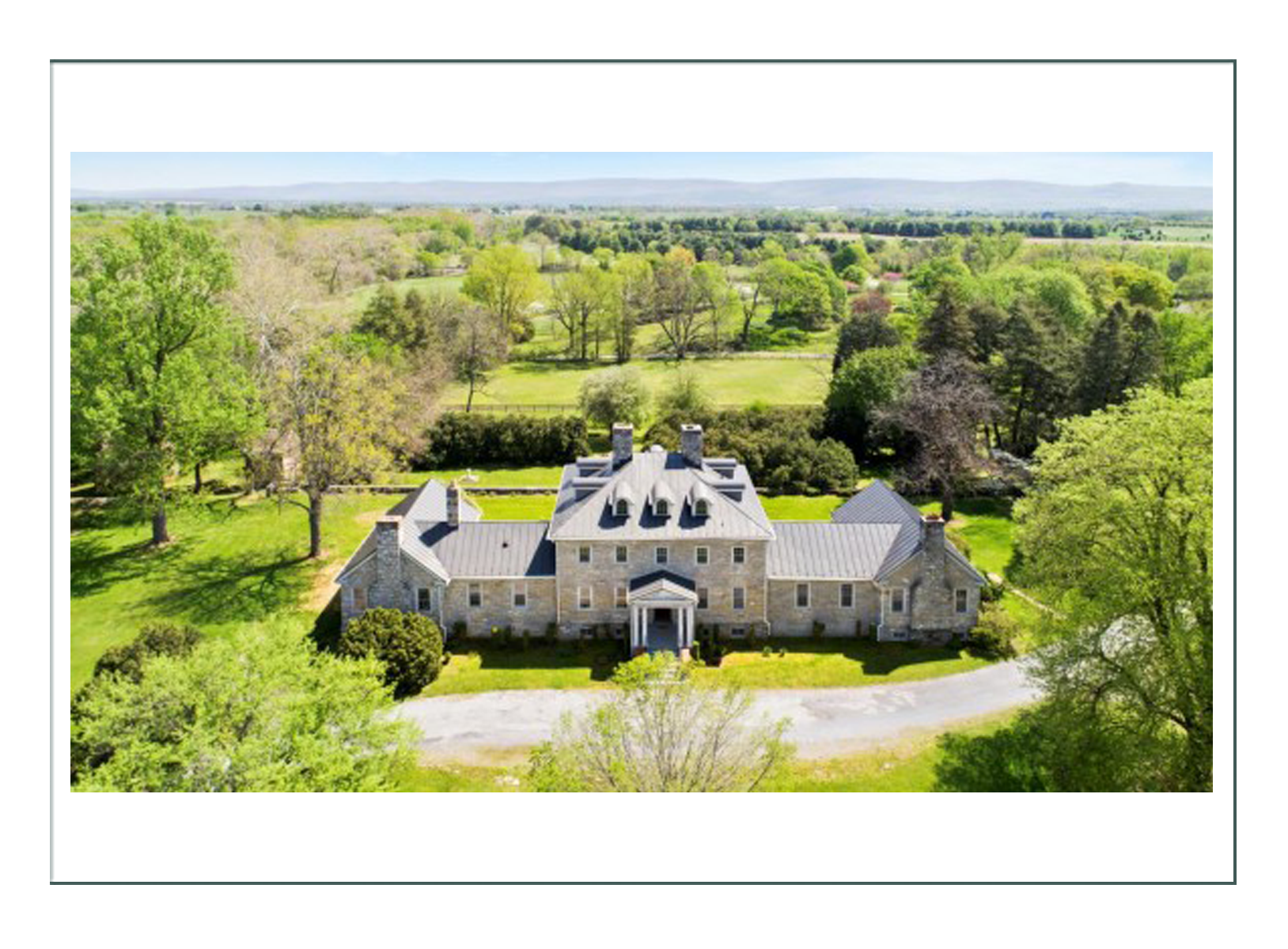

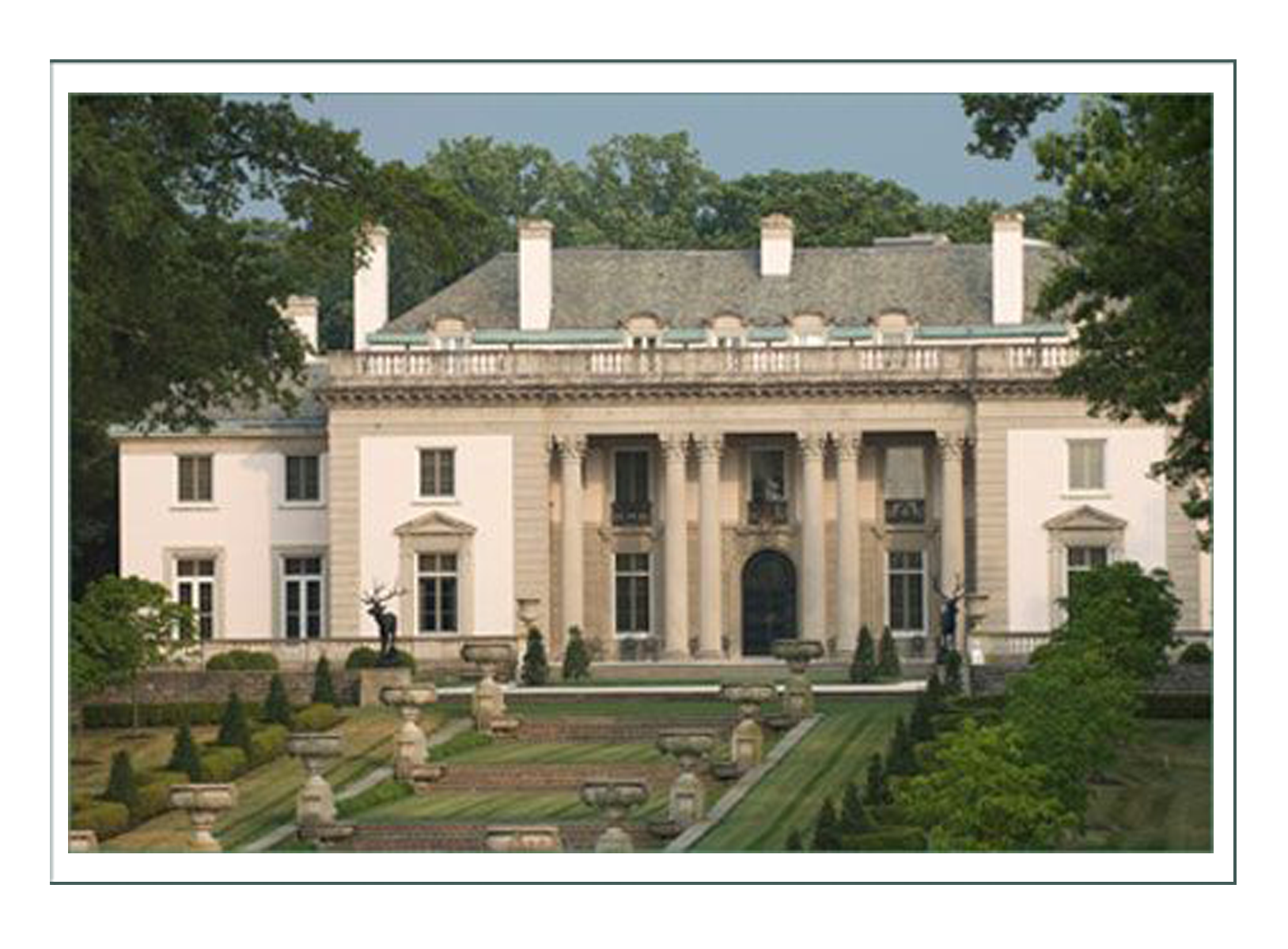

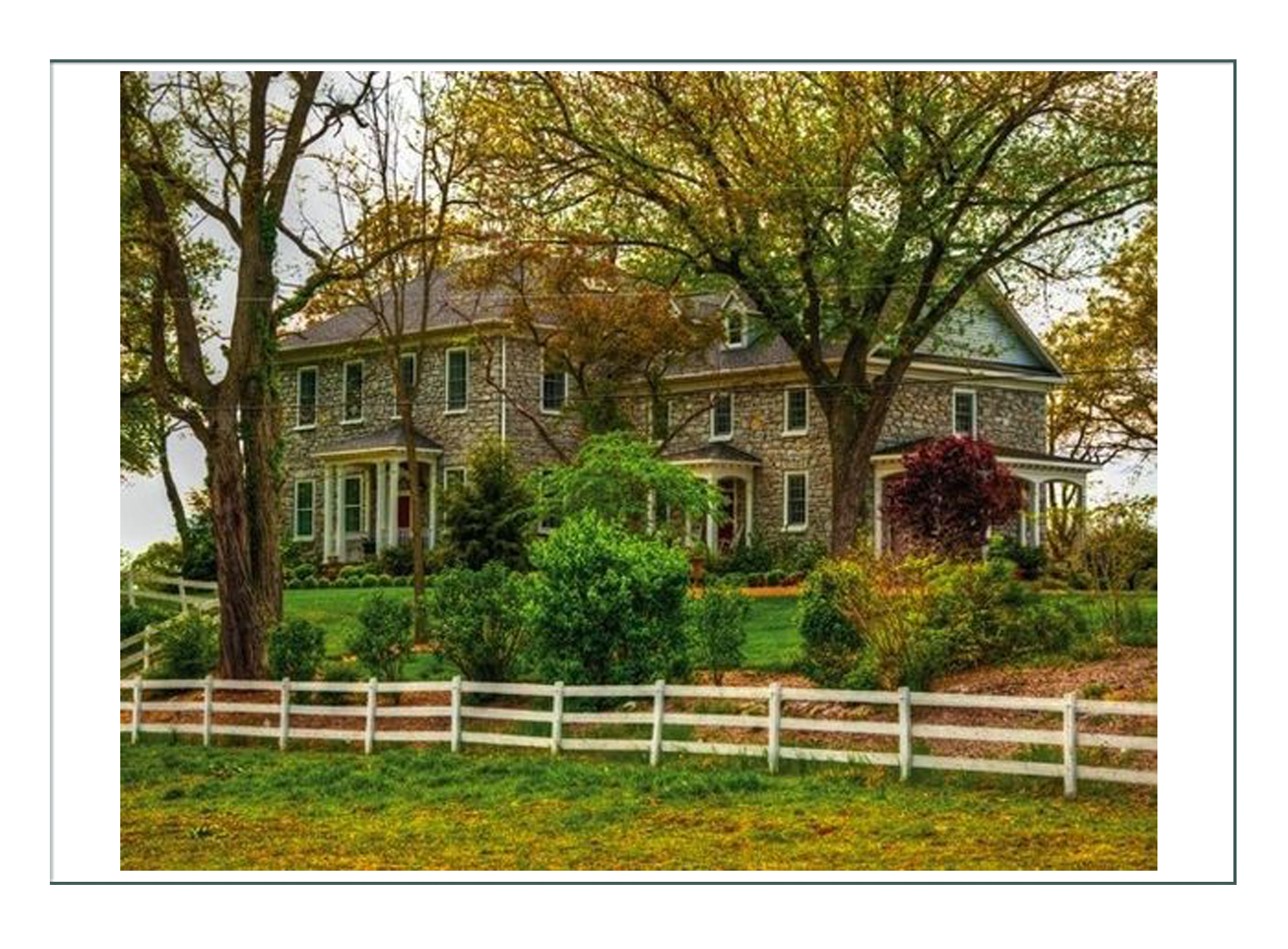

The very fortunate few in America, such as industrial “barons” would live in grand estates built of indigenous materials such as limestone or granite. Most of these were on the eastern coasts with grand views, large properties, and good roads and access to cities and ports. Many had their own shipping wharves.

Between Old and New Worlds

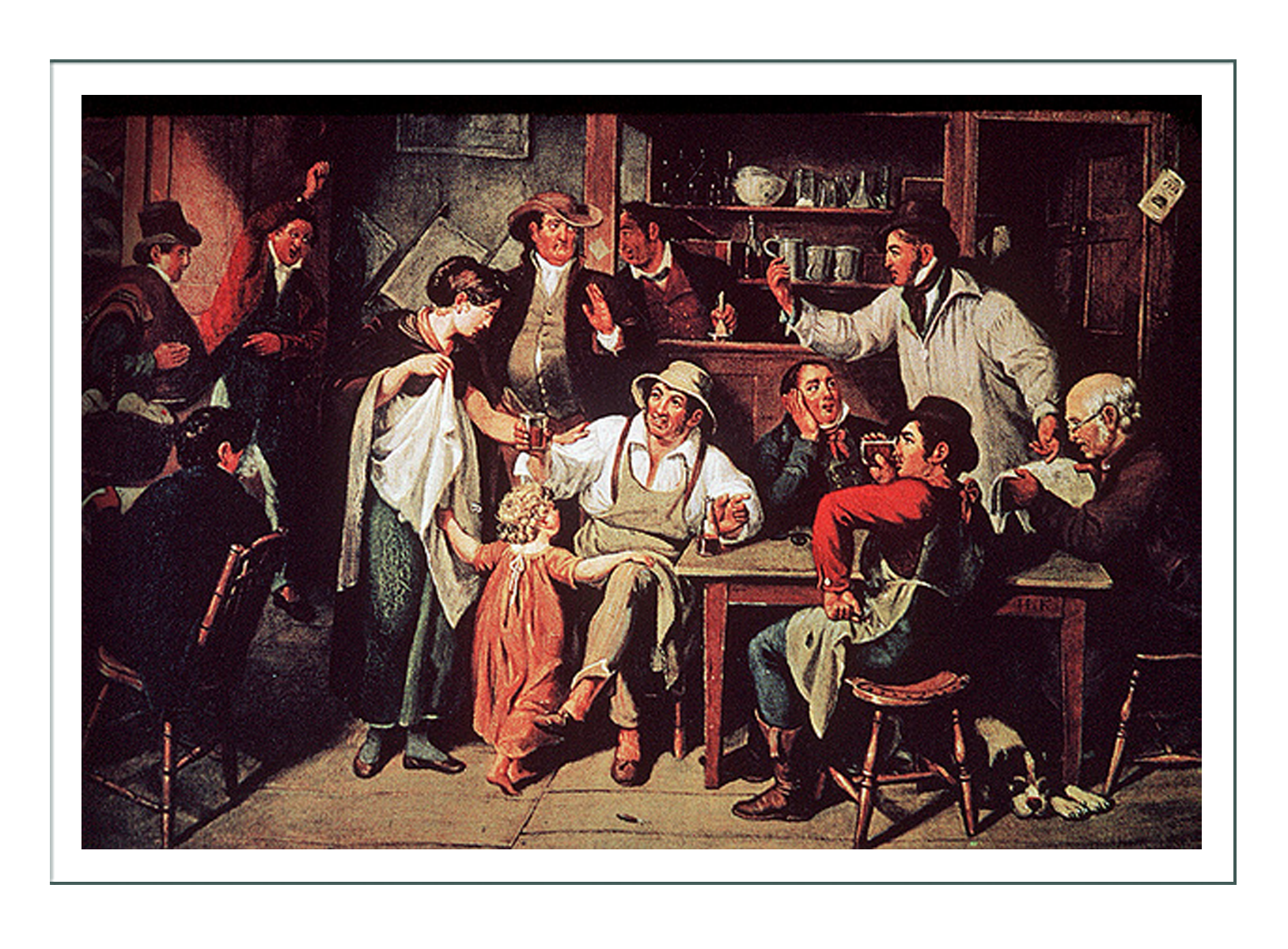

How they Really Lived

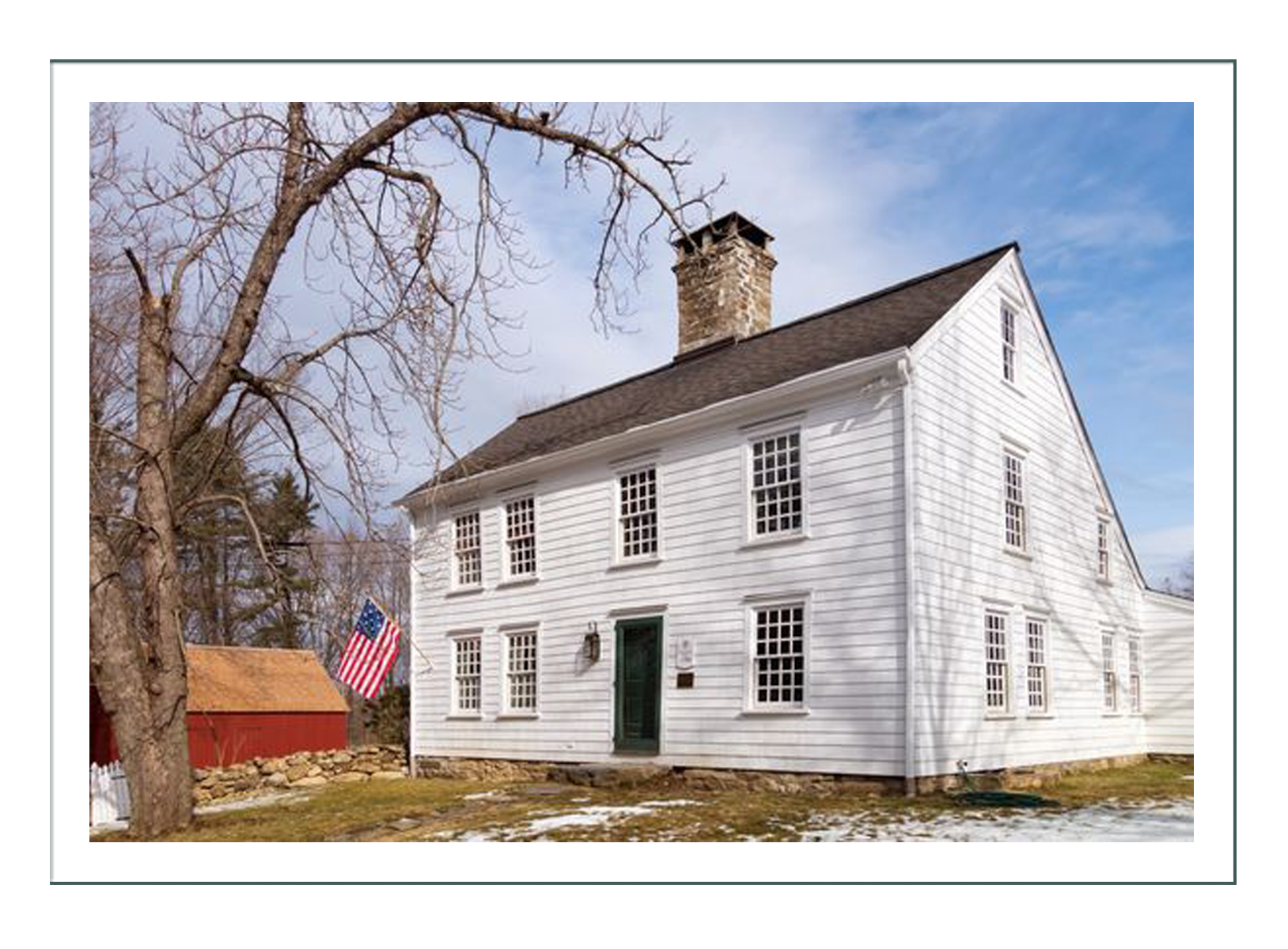

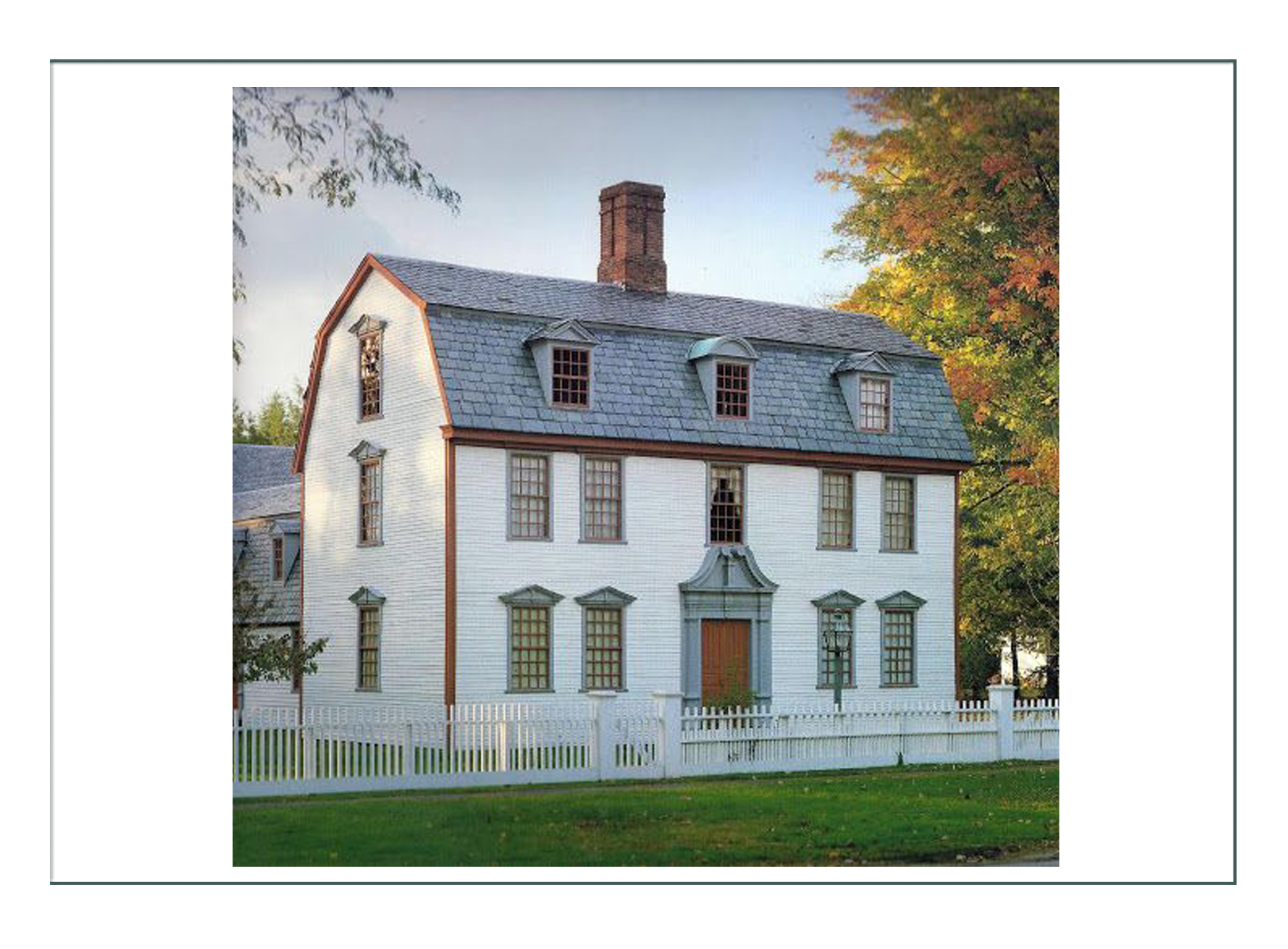

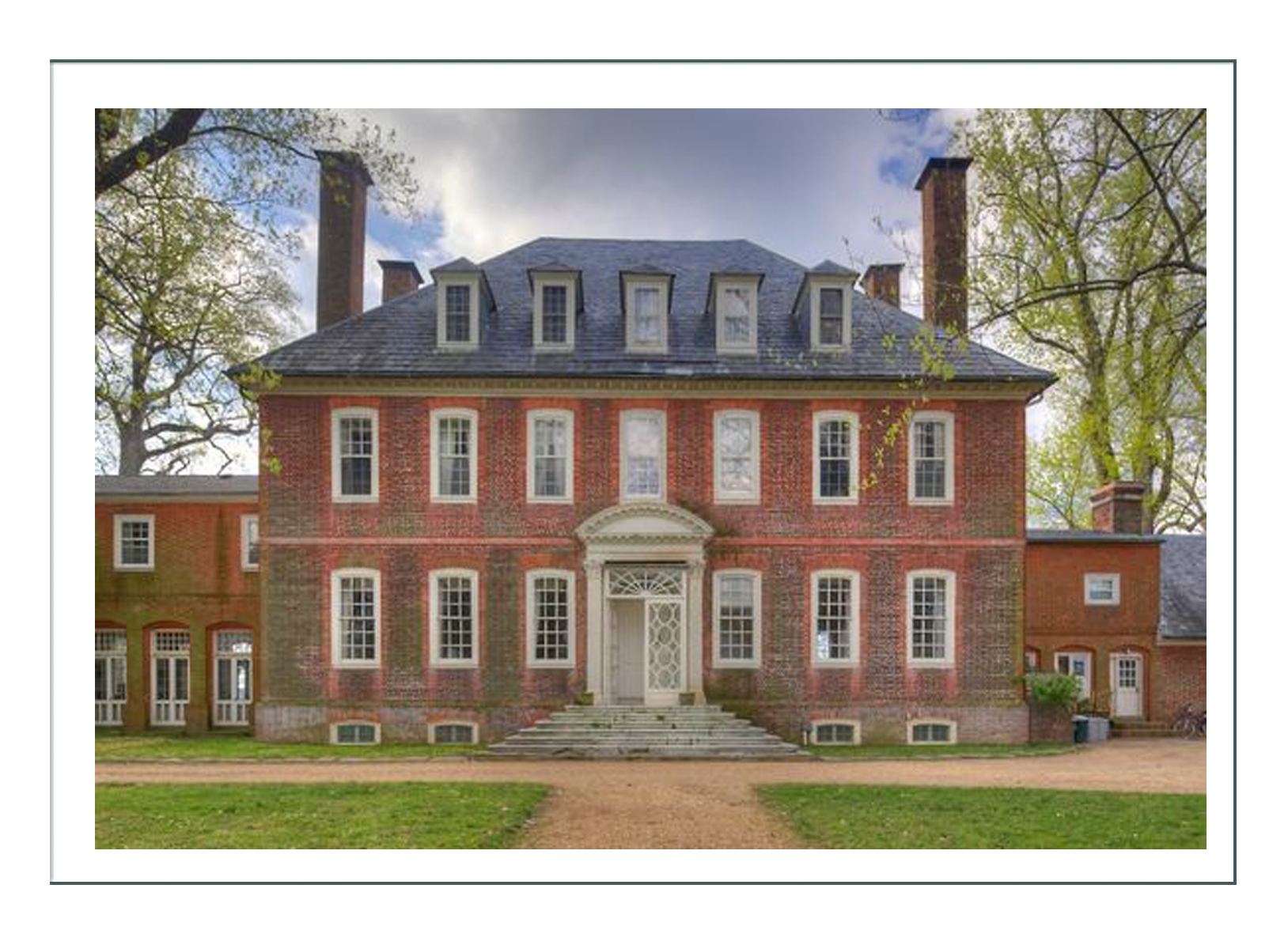

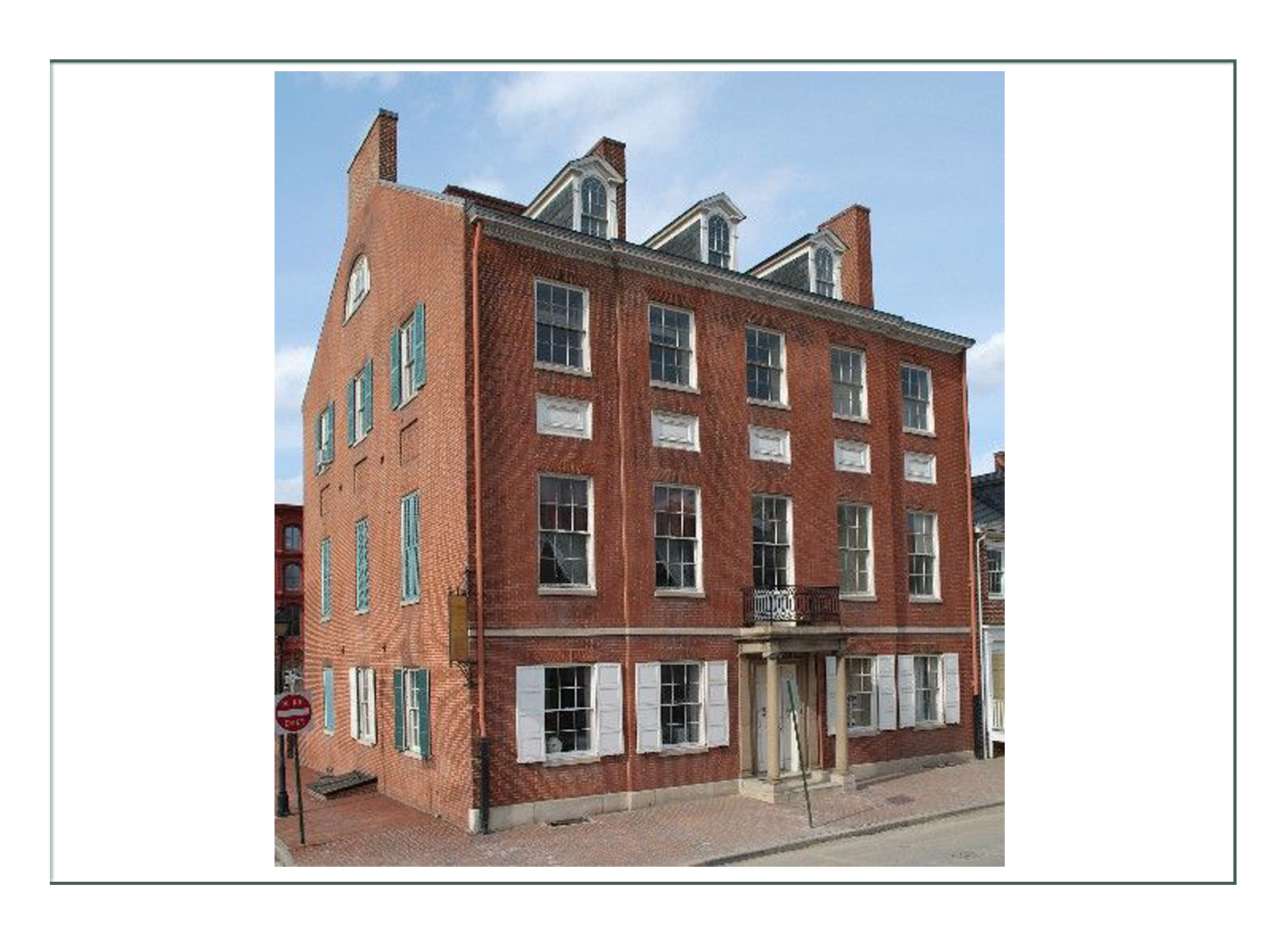

Following are samples of middle to middle-upper class American homes. It is to be noted a family of 1805-09 would most likely be living in an older Colonial or Georgian style home built from 1760- 1800. This would be the time the elder sons of those who fought the Revolutionary War would be taking on the responsiblity of the family home – that most likely having been built prior to the War, or afterwards during recovery.

There is much documentation and restoration of these Colonial and Georgian homes, but little about the years between 1800 and the Civil War of 1860’s. This is most likely due to the fact that during the Civil War, most courthouses and documents in these eastern coastal and colonial communities were destroyed; including records of ownership, deeds, construction drawings, and those historical references that might give better clues to new construction of the time 1800-1860.

It is also of note the westward migration with wagon trains began at the end of the period being depicted. Those social factors including the 3rd and 4th sons of the Patriots having no land, or wanting to seek adventure, etc. along with more information coming back from the explorers by the 1840’s – as well as those wishing to escape the pending war – created an attitude towards settlement and society that meant this time was also at a “line” between what was known and existed, and what the innovators would seek out.

It is into this period of time and place, just on the verge of something exciting and new to happen, that Anna’s character arrives.

World at the Time

- The 19th Century, starting in 1800, was known as “The Steel Age” because history, science, & industry were advancing with key developments in shipping, rail, & other steel innovations

- The century discovered history: spiritual (Hegel), biological (Darwin), economic (Marx), & personal (Freud)

- Mass production began with this industrial revolution

- The textile industry was the first to use mass production due to its spinning, cutting, & weaving advancements

- The French government was in a shambles

- England was at its height: “The sun never set on the British Empire

- America was growing with addition of the Louisiana Purchase

- New American heroes like Daniel Boone made the Wild West fashionable

- Literary heroes like those in the book “Wuthering Heights” brought a romanticism to the era

- Communication & trade were increasing as relationships between America & Europe mended

- The common man was challenging the class & bourgeois concept in search of equality

Tying the Character to Baltimore and the Ridgelys

Baltimore, Maryland has a unique history specific to the development of Anna’s character. Playing a major role in that history, and linking it to the world situation, newly established United States, and specific people, Anna finetunes her time, place and character as the last step before developing her costume.

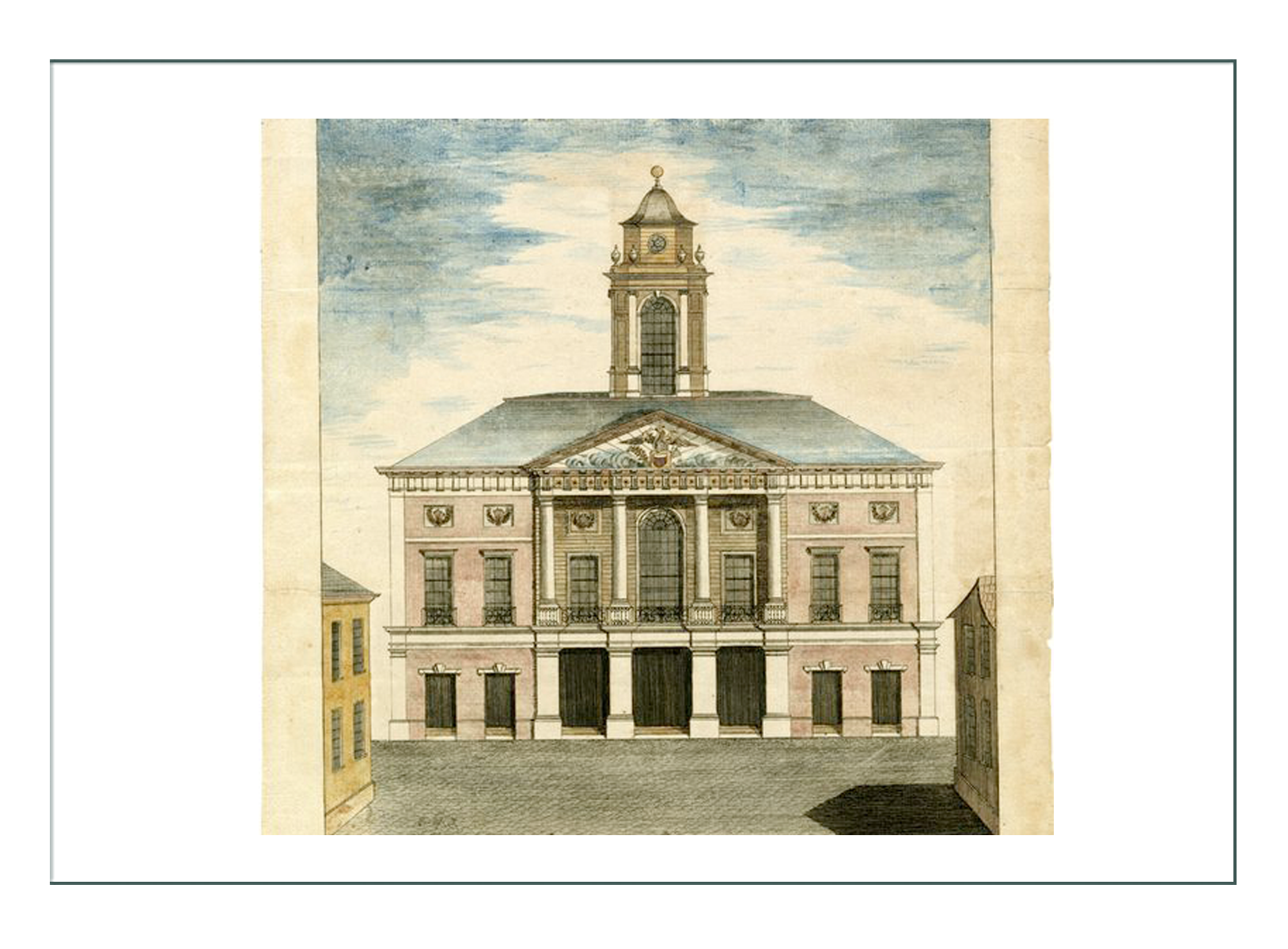

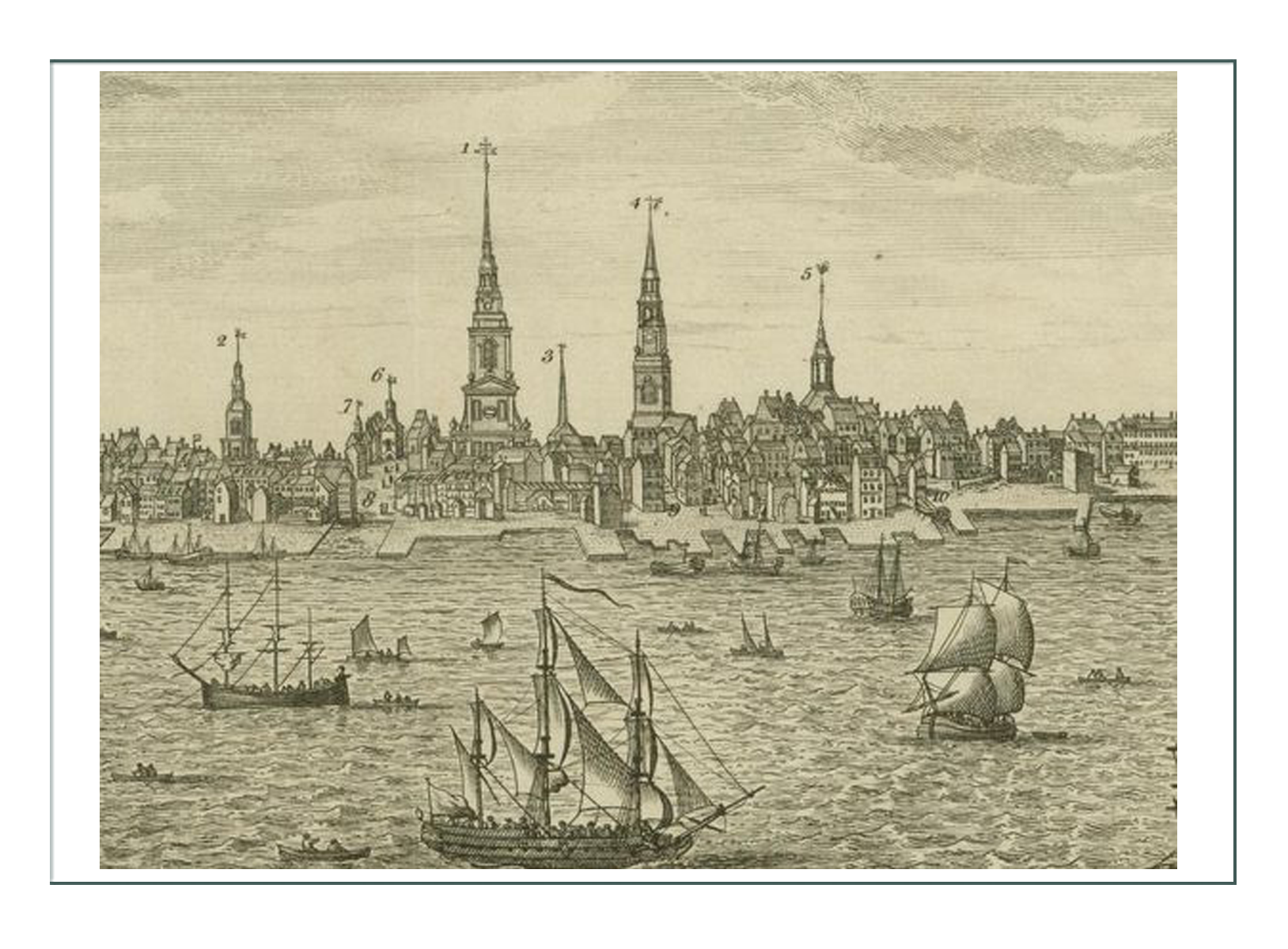

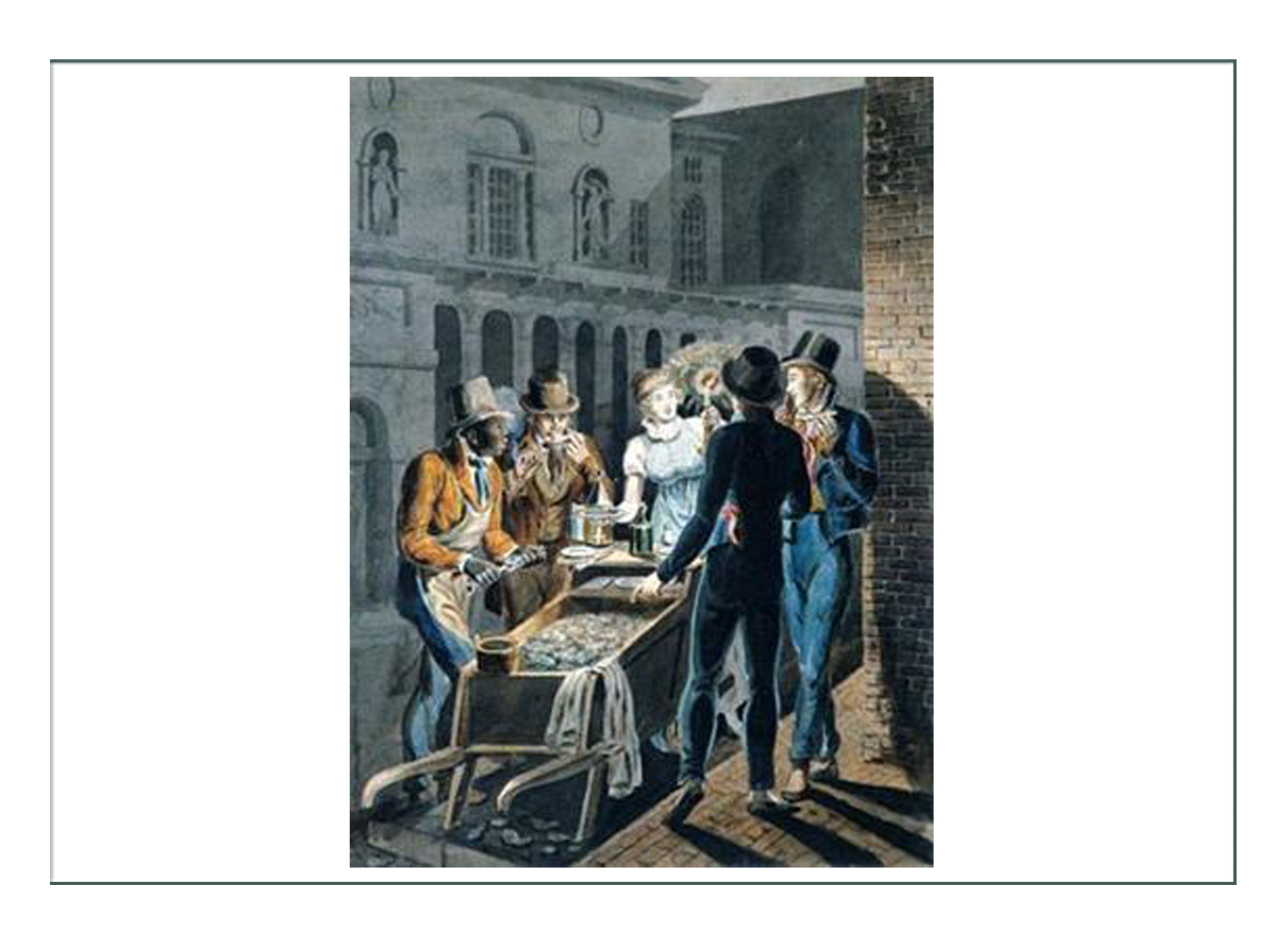

Baltimore Is Found, Founded, with Foundries

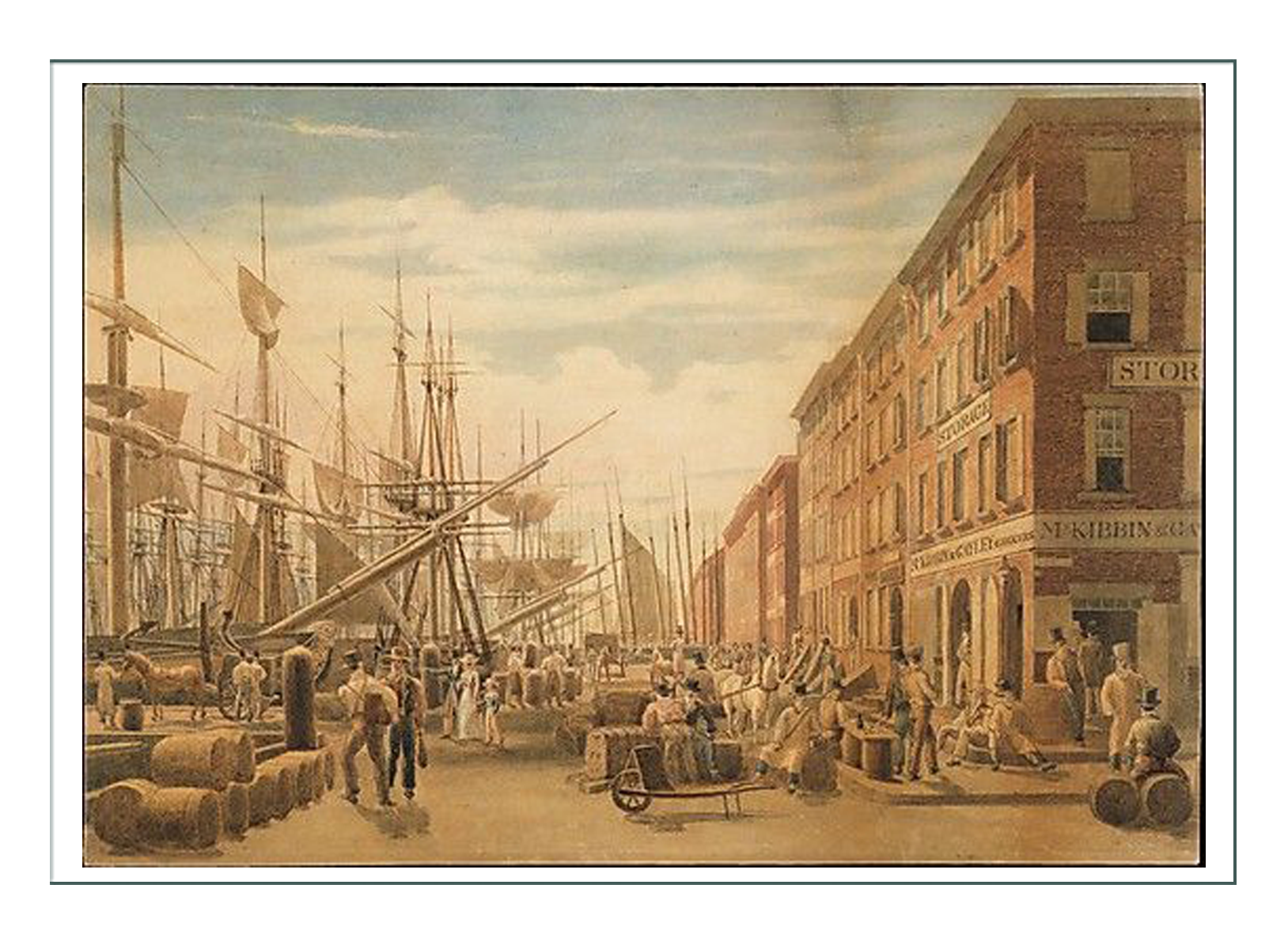

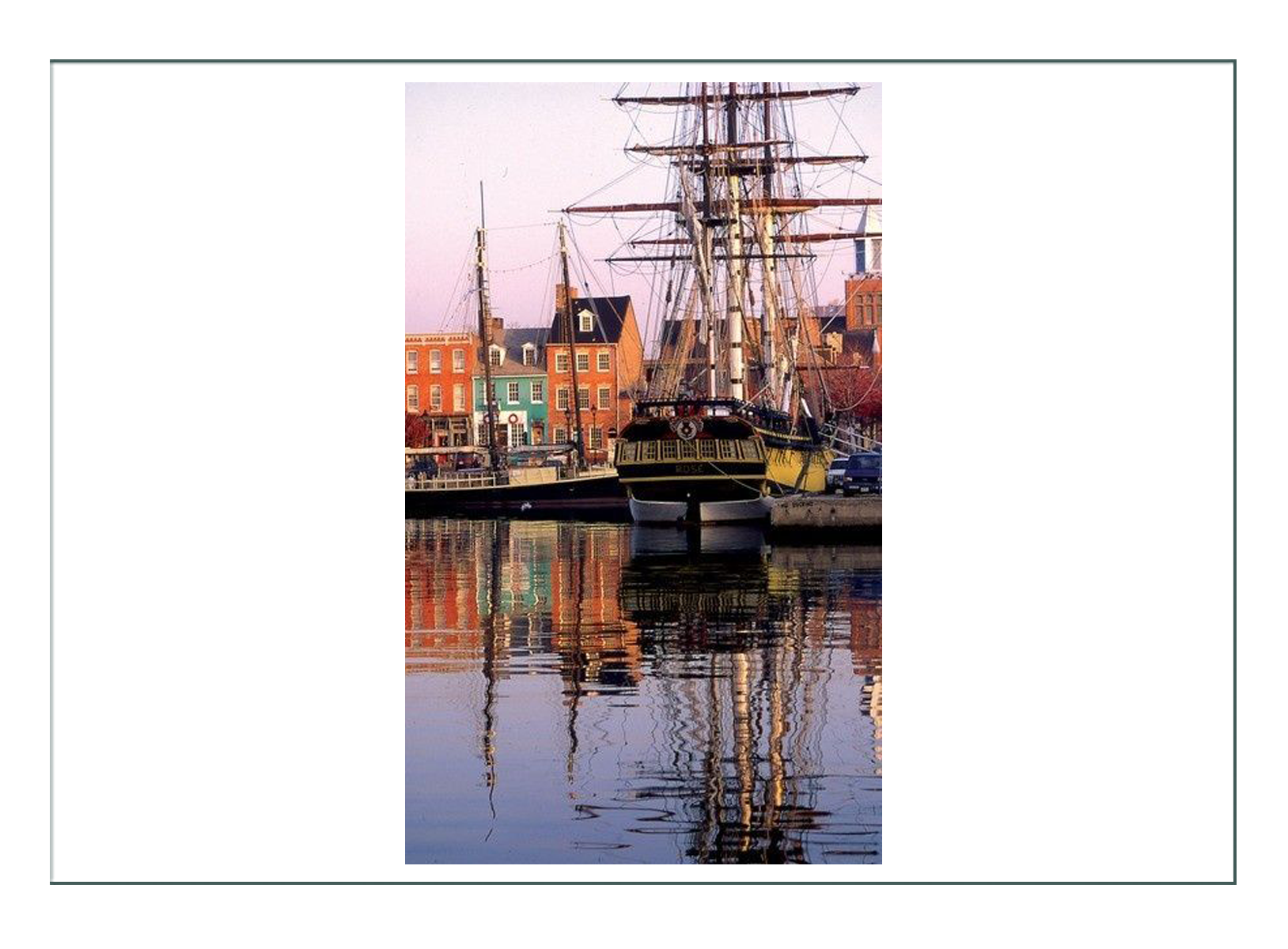

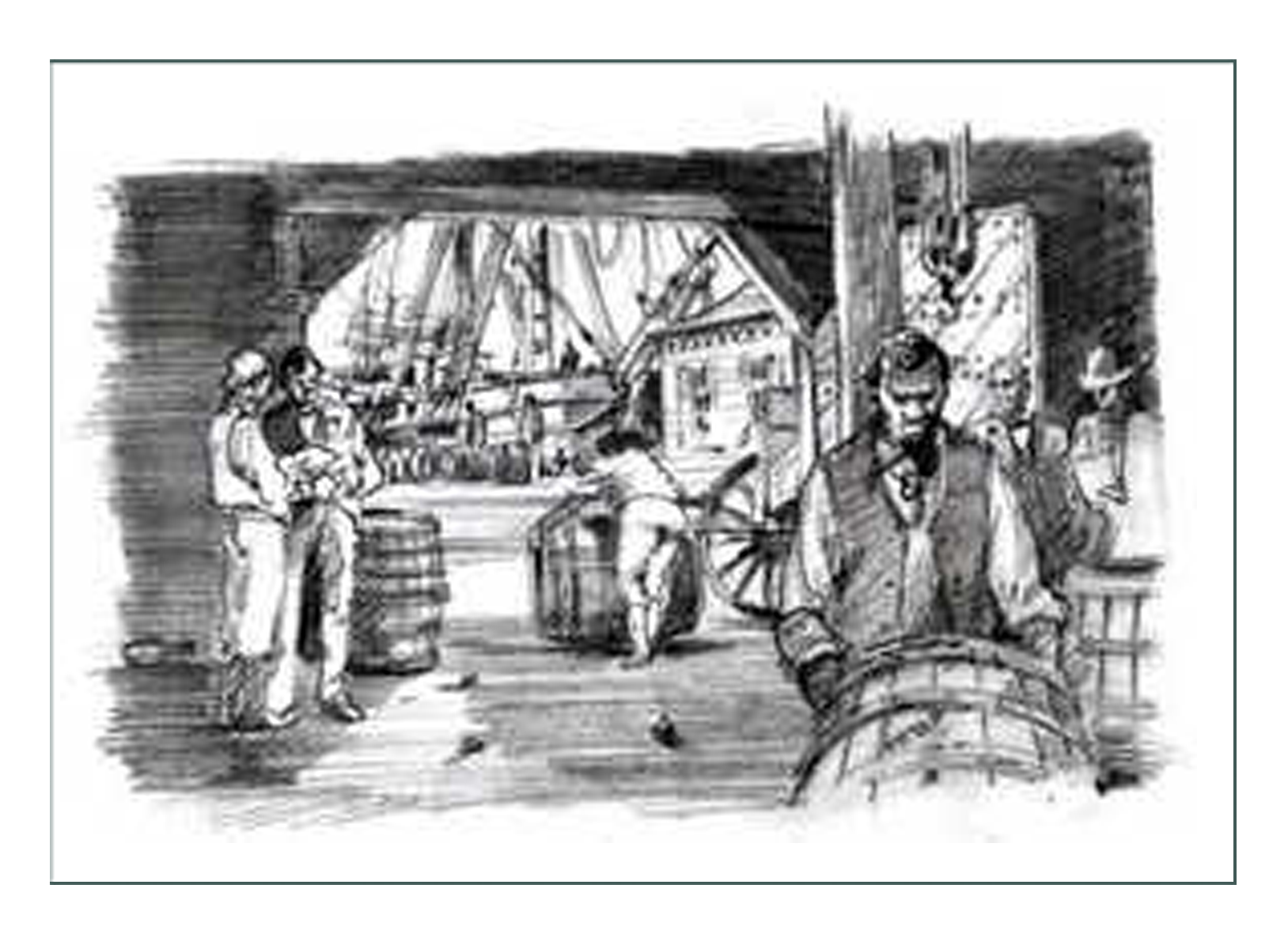

Officially founded in 1729, Baltimore’s location as an eastern and one of the earliest seaports for the American colonies set it up as a key player from that date forward. Trade with Europe was the basis for its early success: Maryland provided raw goods to Europe, and Europe returned finished goods.

By the 1740’s, Baltimore’s regular exports included tobacco and flour with other grains from its mills which were located along the inland river. These were sent not only to England, but also to the sugar-producing colonies in the Caribbean.

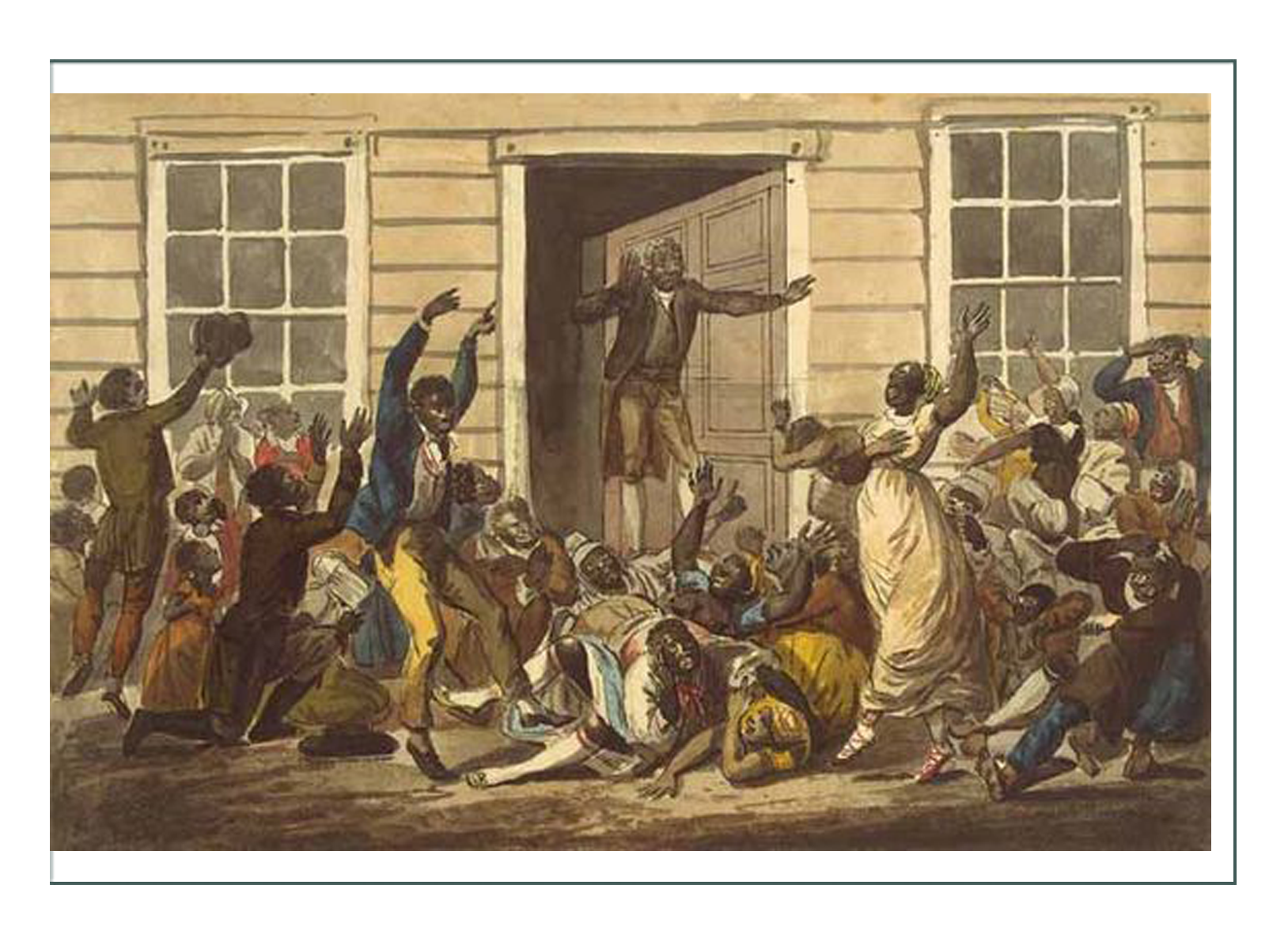

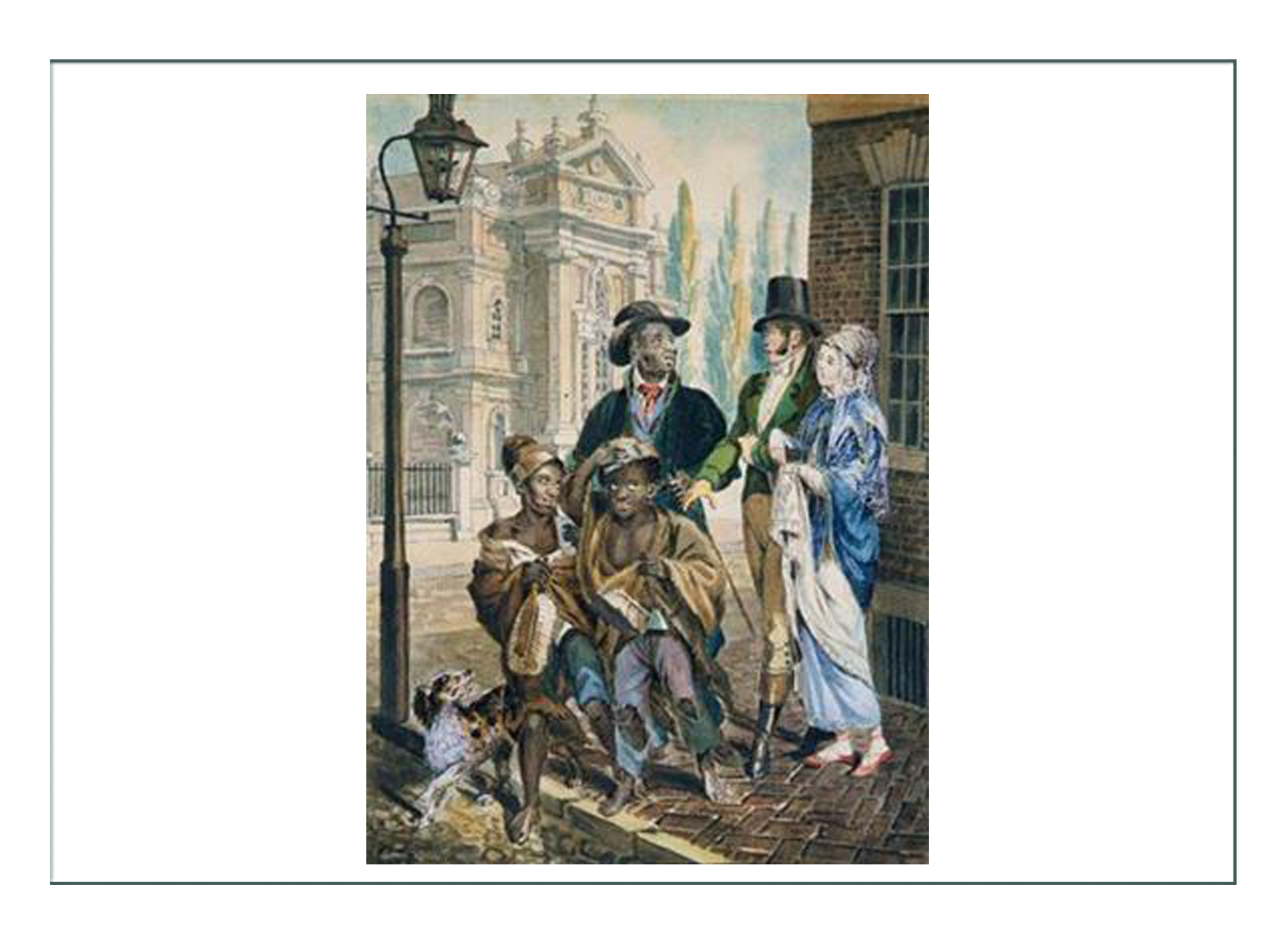

Indentured Servants & Slaves

Playing a key role in early success, Baltimore businesses employed servants indentured (required to serve a number of years in exchange for their freedom; supposedly English convicts, but also alledgedly employing a lively trade of dubious indenturement of free persons).

Later, and long after it was abolished in England, they had slaves. Although technically a union state in the later War Between the States, they were slave holding in Baltimore.

Revolution

Baltimore and the region were key to the turn of events before, during, and after the Revolutionary War or War of Independence from Great Britain. Maryland had the most lively and direct trade with England; when Baltimore was required to stop all trade due to the Patriot cause, it severely impacted the region.

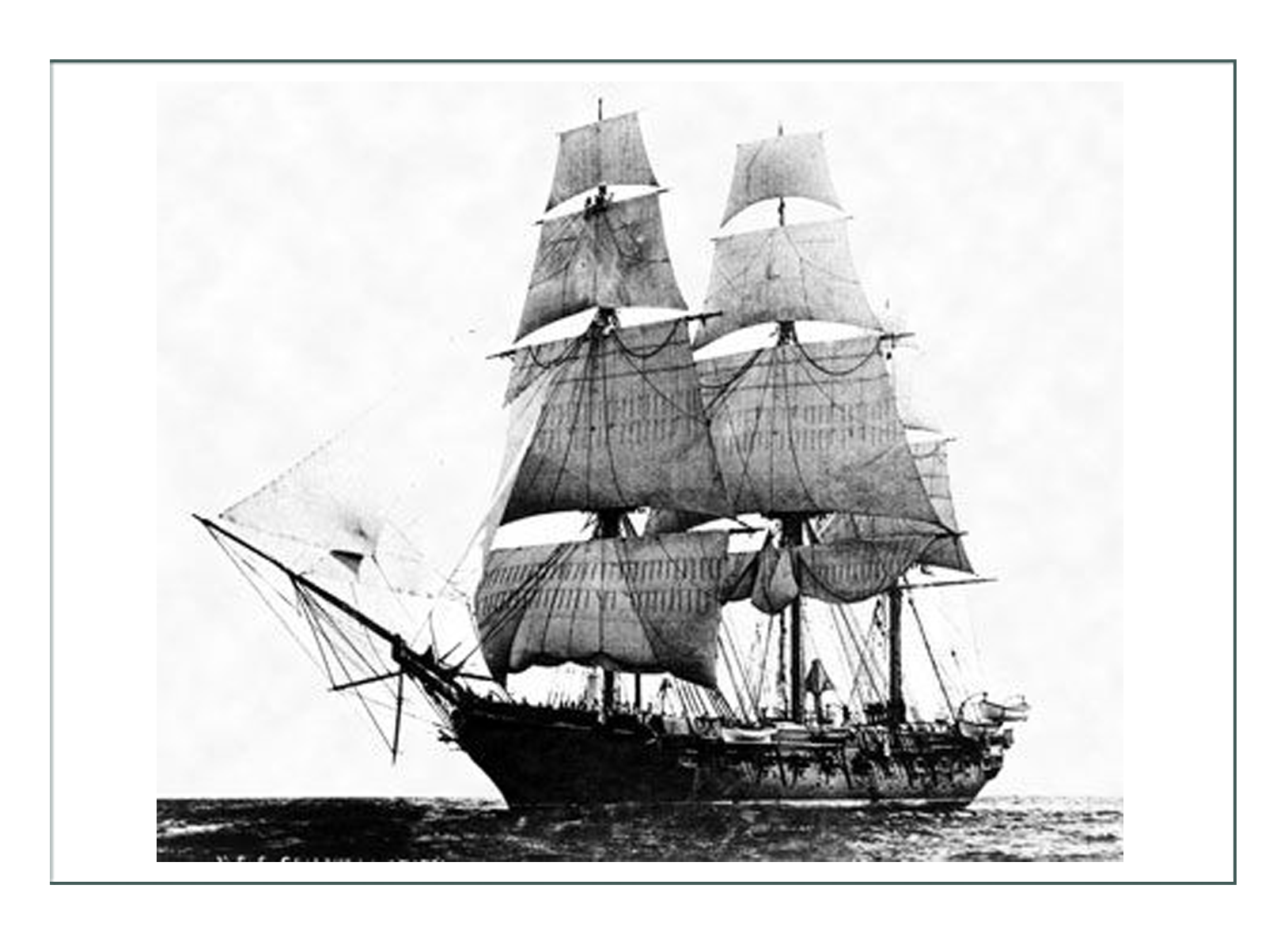

After the war, trade with England was promptly and effectively resumed almost before the rest of the United States made amends. This was largely due to shipbuilding, which the locals had benefitted from during the War. Fast merchant ships were in great demand, and Maryland had the natural resources – iron, coal, wood – from which to build them, and the knowledge.

Business of all sorts, including expansion of the previous exchange of raw goods for finished flourished.

War of 1812 & Beyond

War of 1812 & Beyond

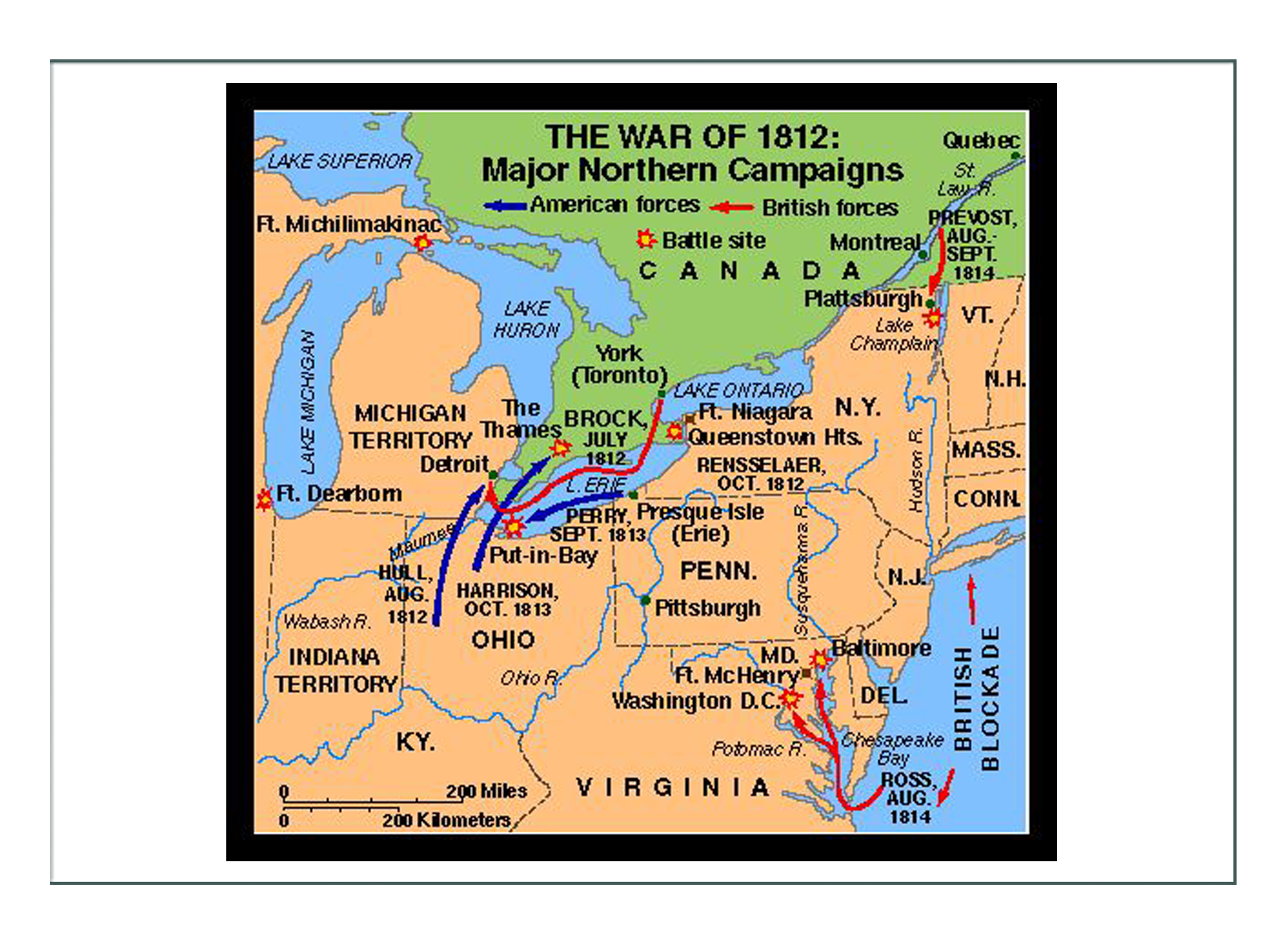

The good times with the British were not destined to last. Once again, when tensions over territories and agreements grew between the United States and England, it was the Baltimore trade that felt it first.

From 1800-1810, Britain interfered with trade again as it had in using trade to control politics and economics. They stole American military men and forced them to work for Britain. Since many of those were sailors from Baltimore, and because it was Baltimore’s trade that was most impacted by restrictions, Baltimore was among the first to call for war (again) against Britain.

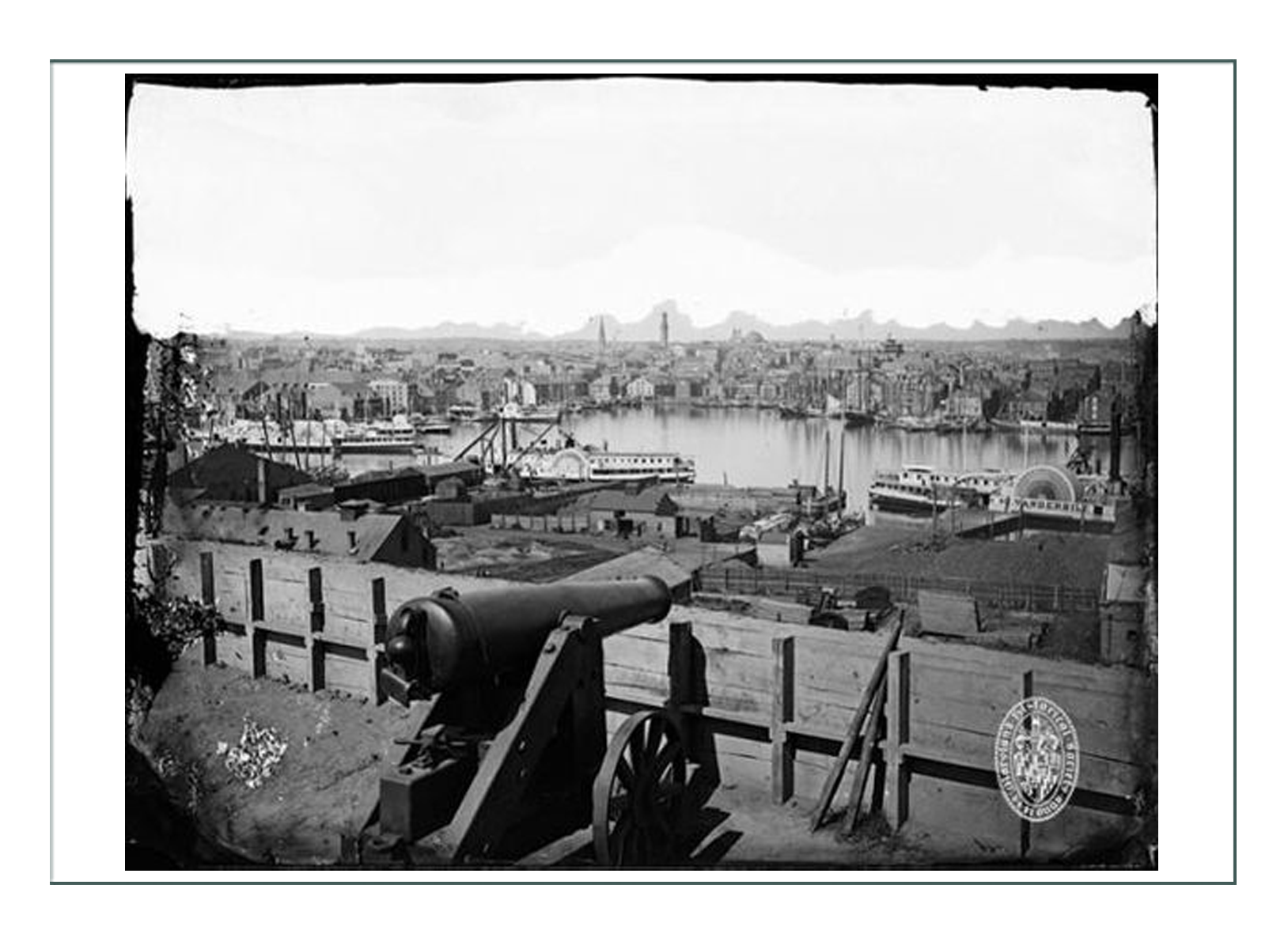

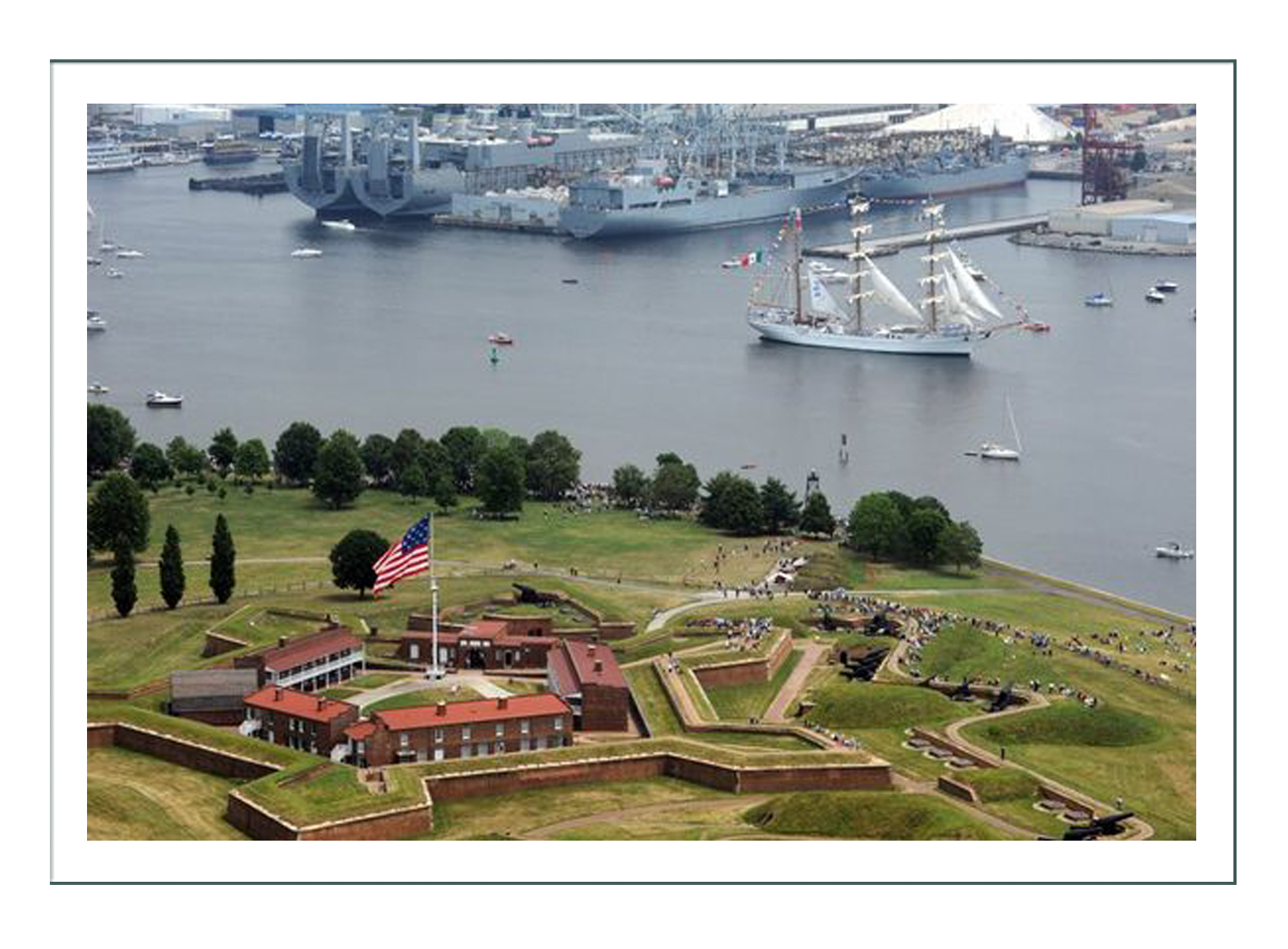

It was Baltimore Harbor’s sea port Fort McHenry the British first fired upon that started the war. It was here that Francis Scott Key say the “Star Spangled Banner yet wave”.

Not to be dimmed, the United States once again thwarted the invasion, and Baltimore boomed, mostly because of new private interests in the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad that would take Maryland into the future.

A few interesting spots in the City

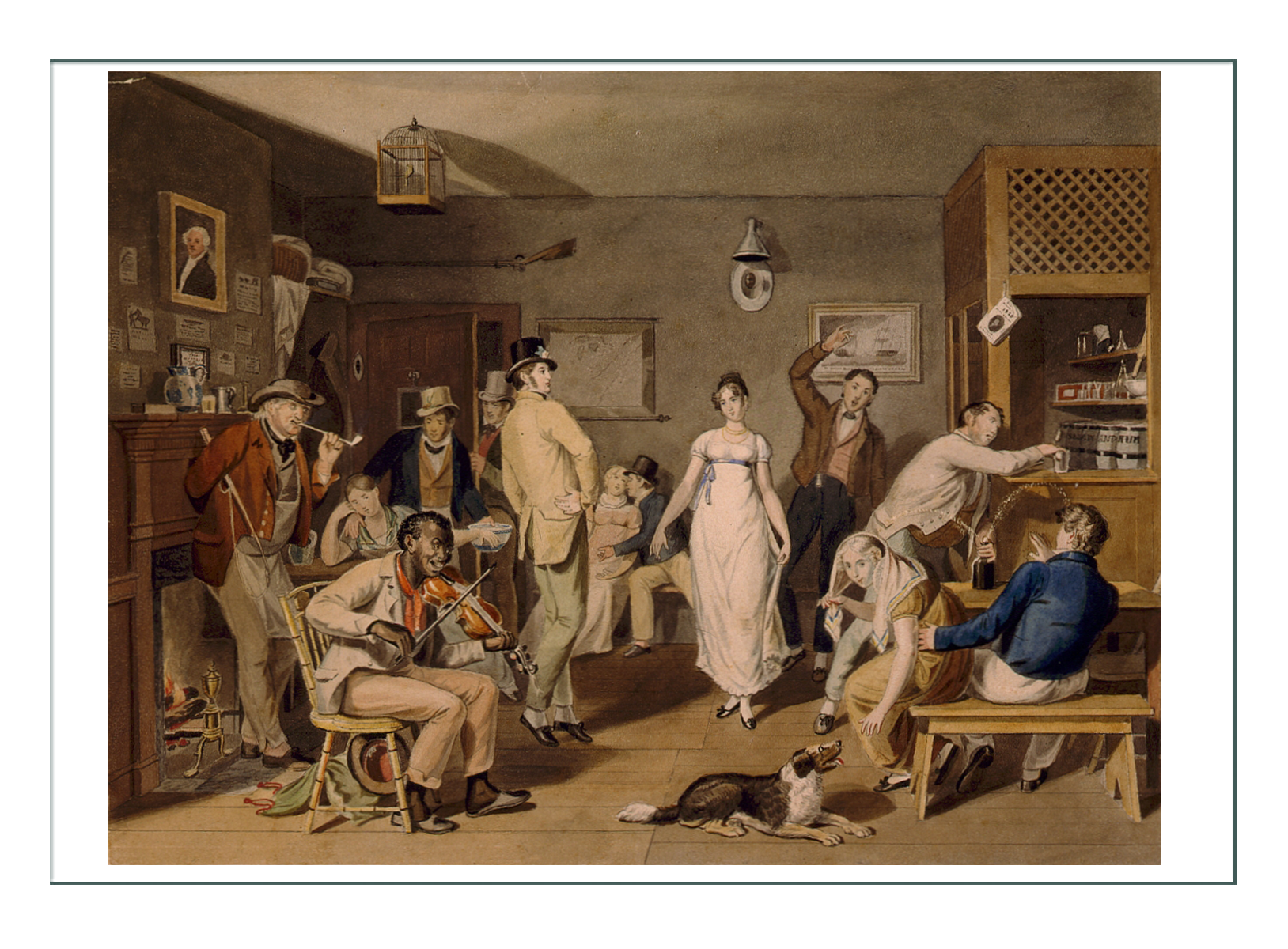

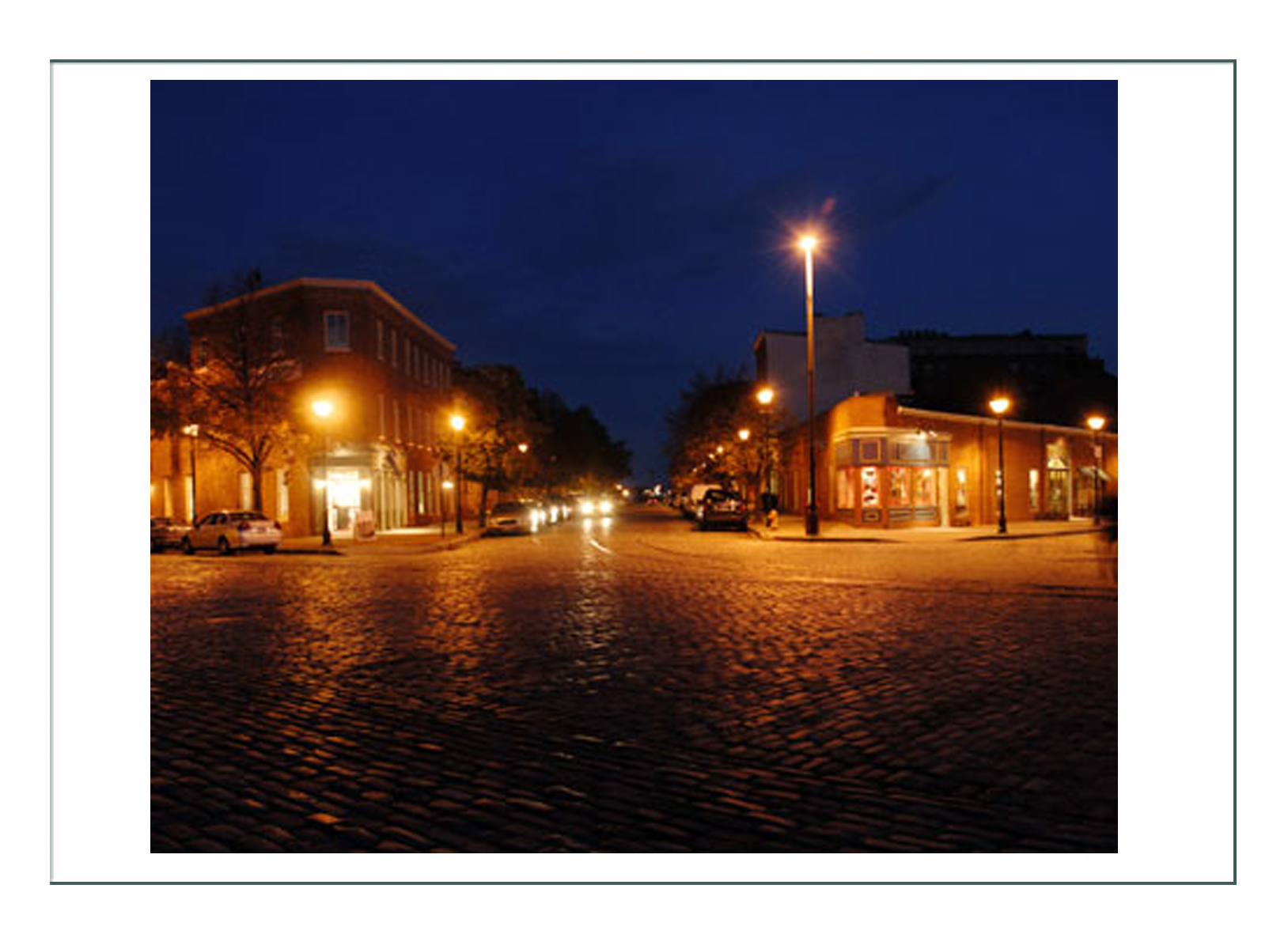

Fells Point, where the shipyards flourished throughout the ups and downs of war and economics, officially founded in 1763 and made a part of Baltimore in 1773, was a flourishing community of support services to the workers and industries at the harbor. It continues today to have at least 3 of the original pubs and restaurants still going strong as a social and economic hub of the city.

By the early 1800’s, Baltimore was the largest city in Maryland, and the 3rd largest in the United States. By 1804, with the Gun Powder Copper Works mine, 1809 Union Manufacturing Textile Mills, and the 1816 Warren Textile Mill, by 1810 Baltimore had become not only a shipping and railroad trade hub, but also a key in production of raw and finished goods for the whole United States.

Other History

The story of Baltimore continues through the Civil War, changes in trade and industry, and continued economic strife. Many of the buildings still stand, and renovation efforts are underway to save the townhouses and mansions in the inner city.

Hampton Estate

Hampton Estate

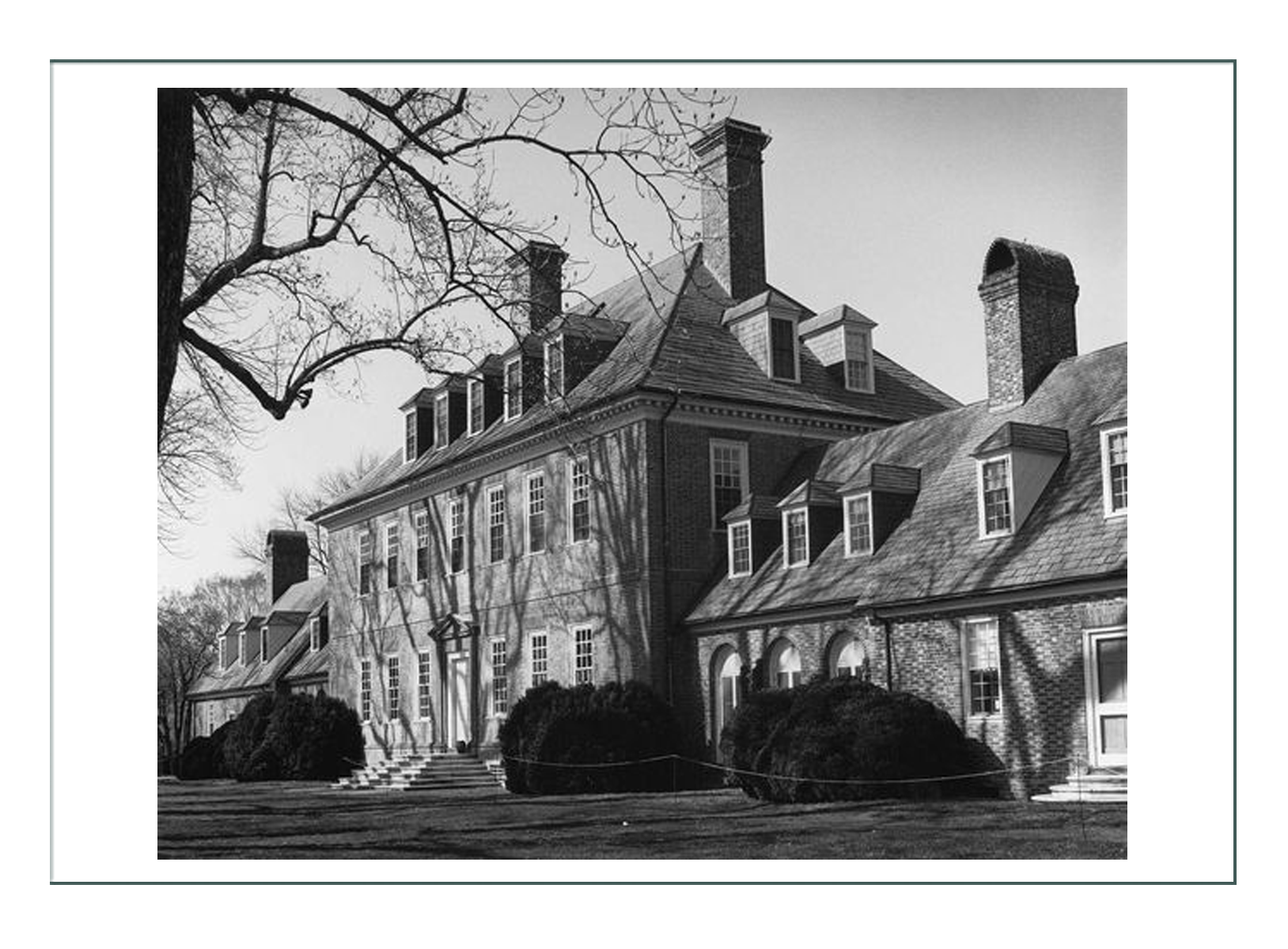

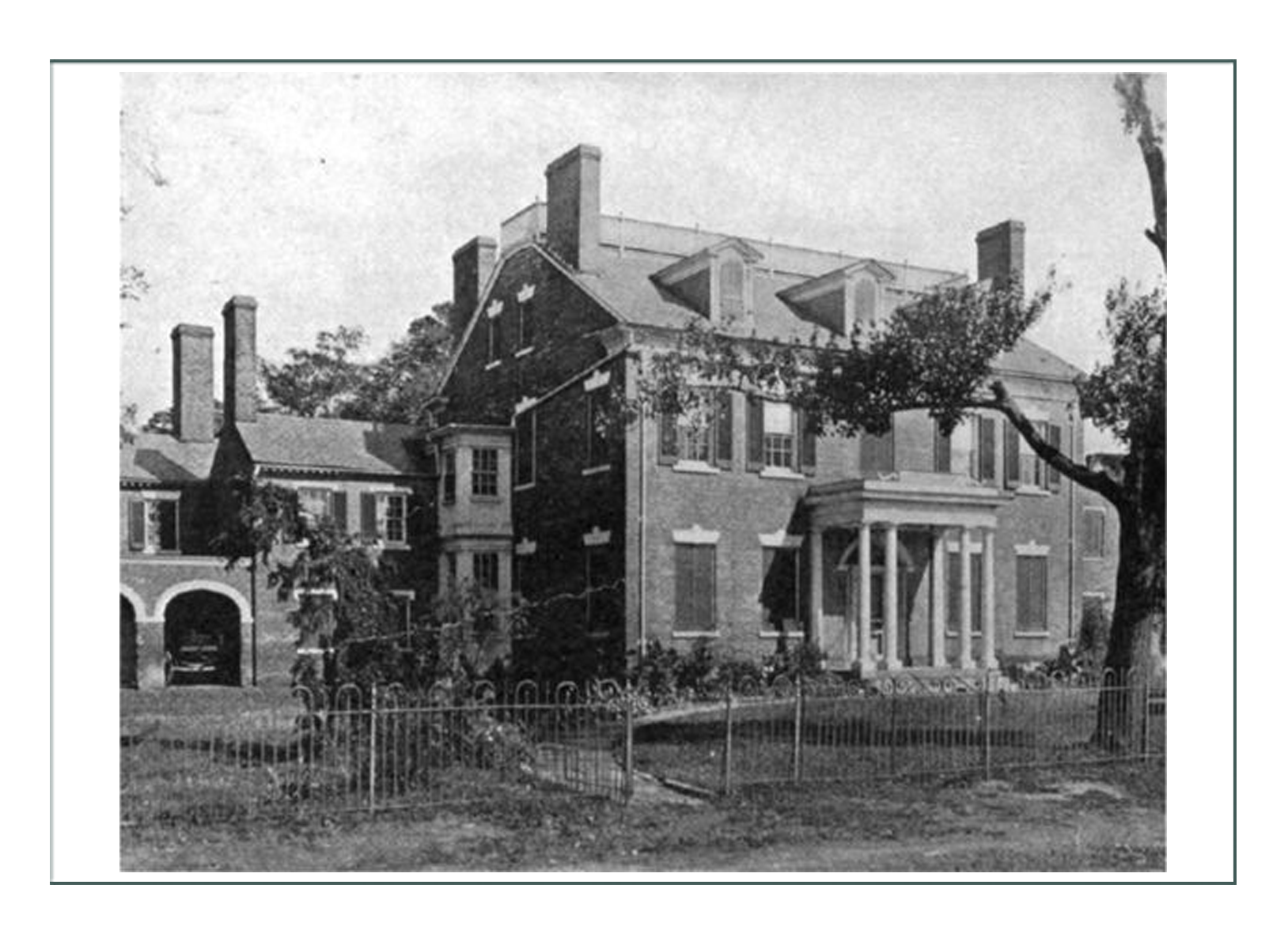

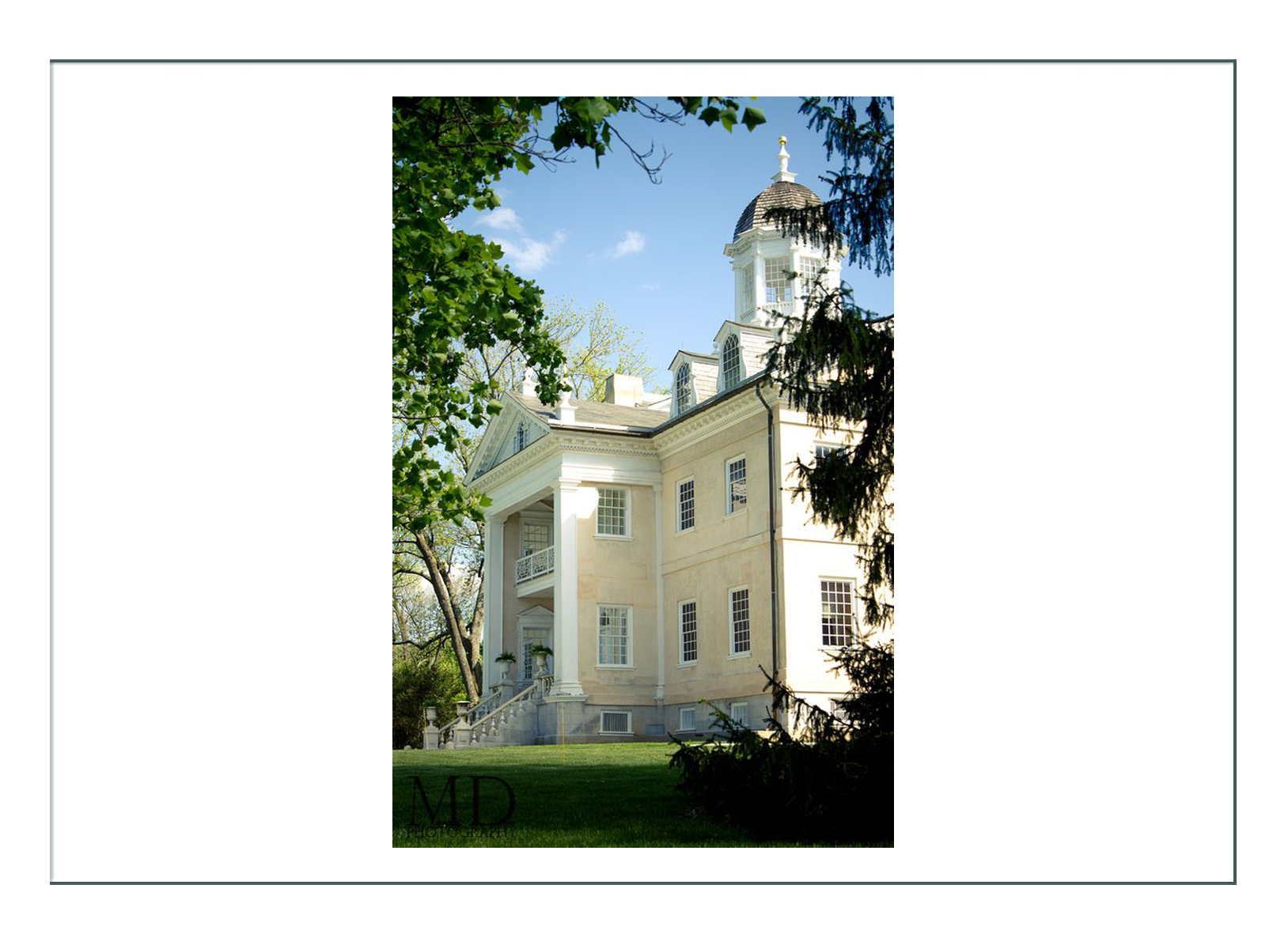

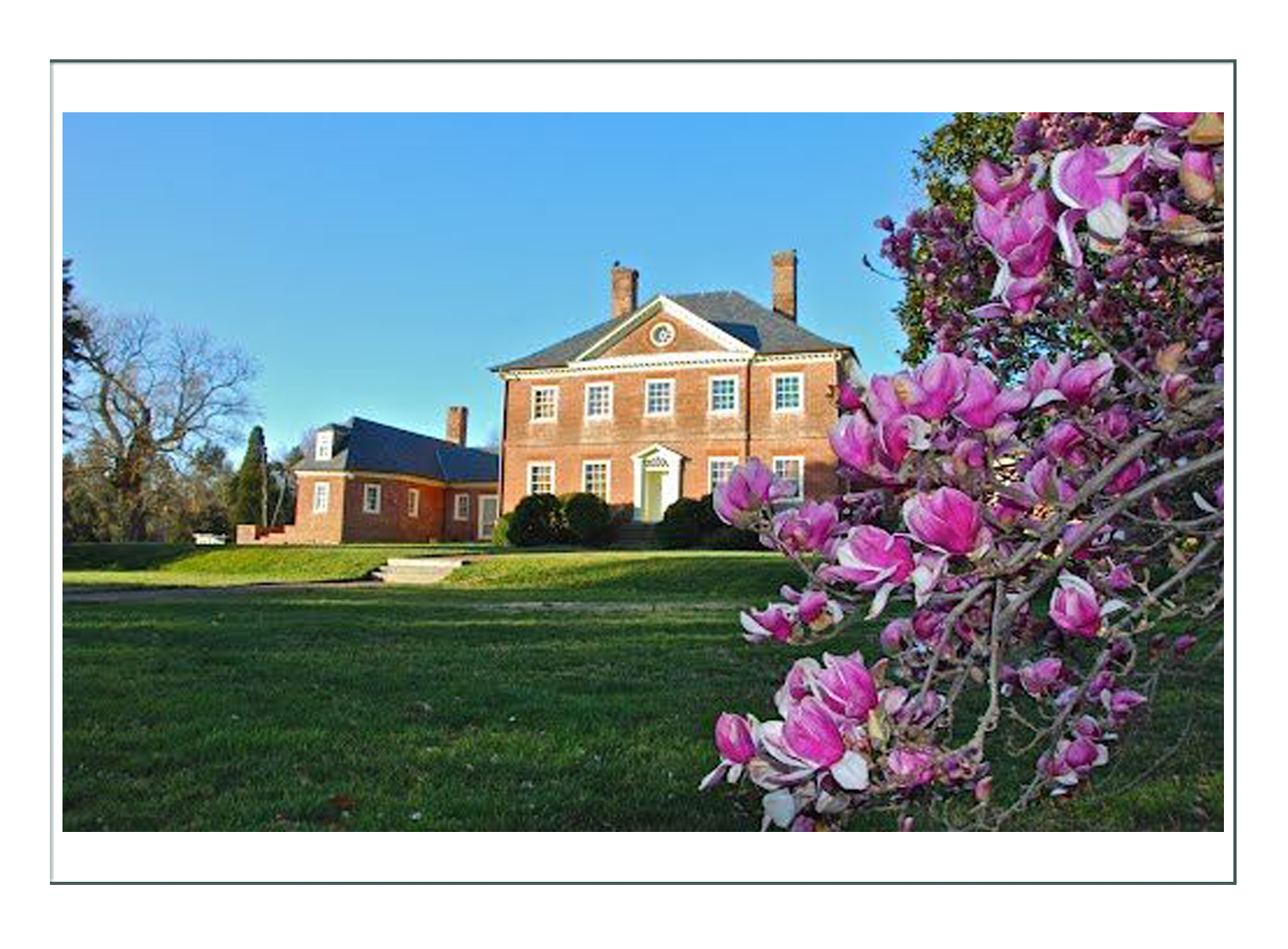

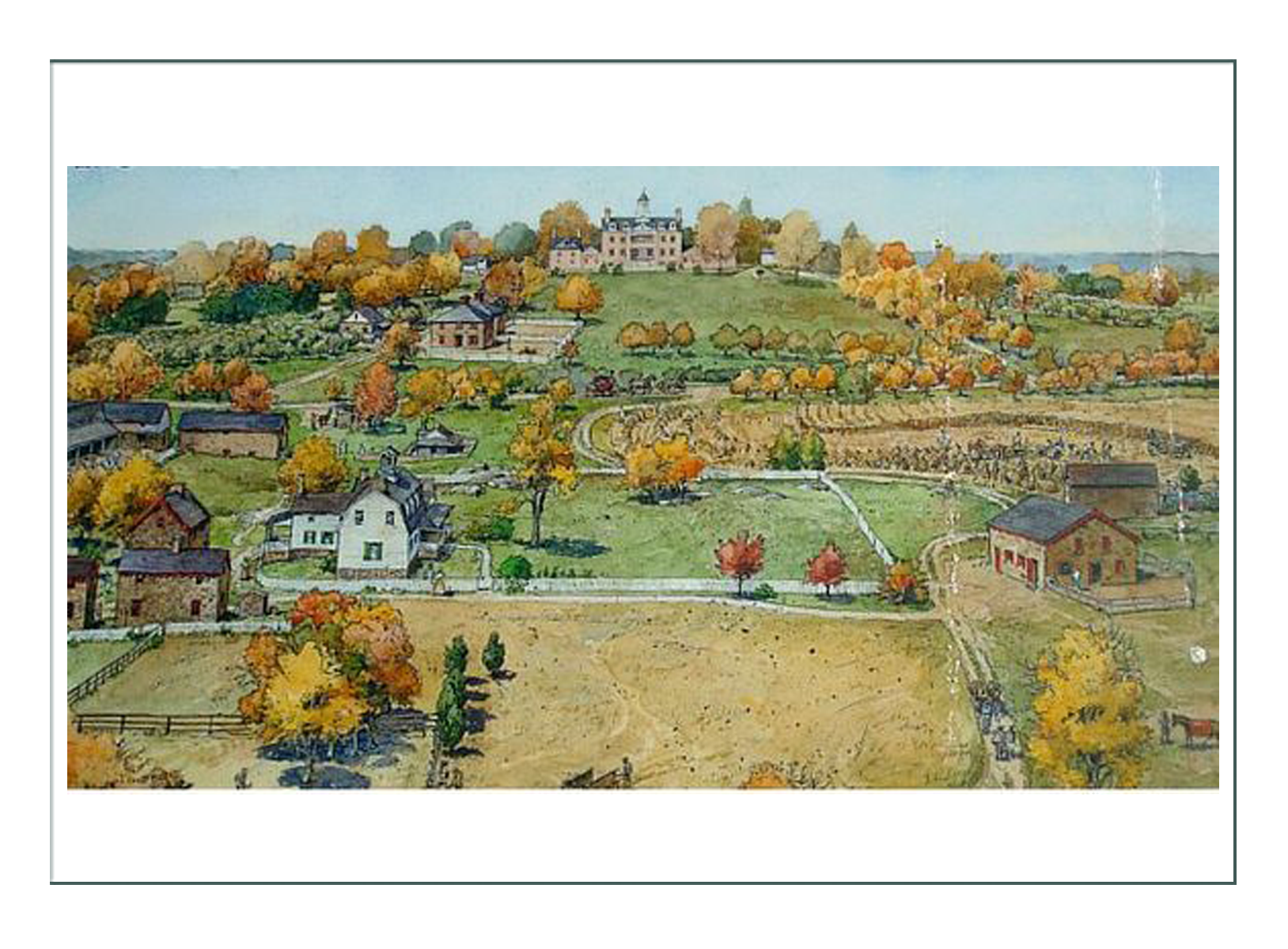

1500 acres of one family owned, Hampton, its people, its time, and place, is perfect for Anna’s character. Not only does it embody the typical flourishing upper-middle class of the new United States, but it brings together American history past, and up to 1805.

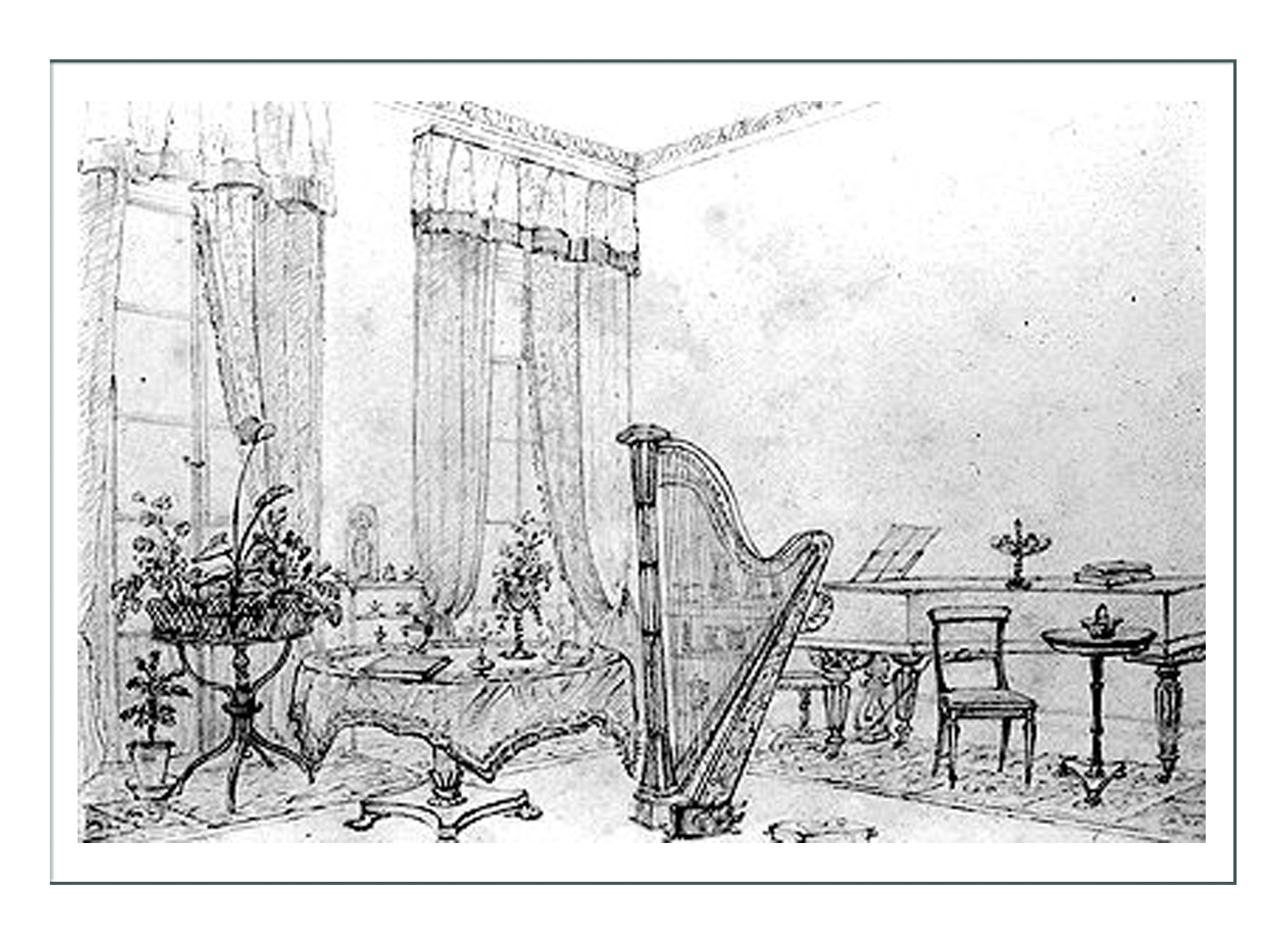

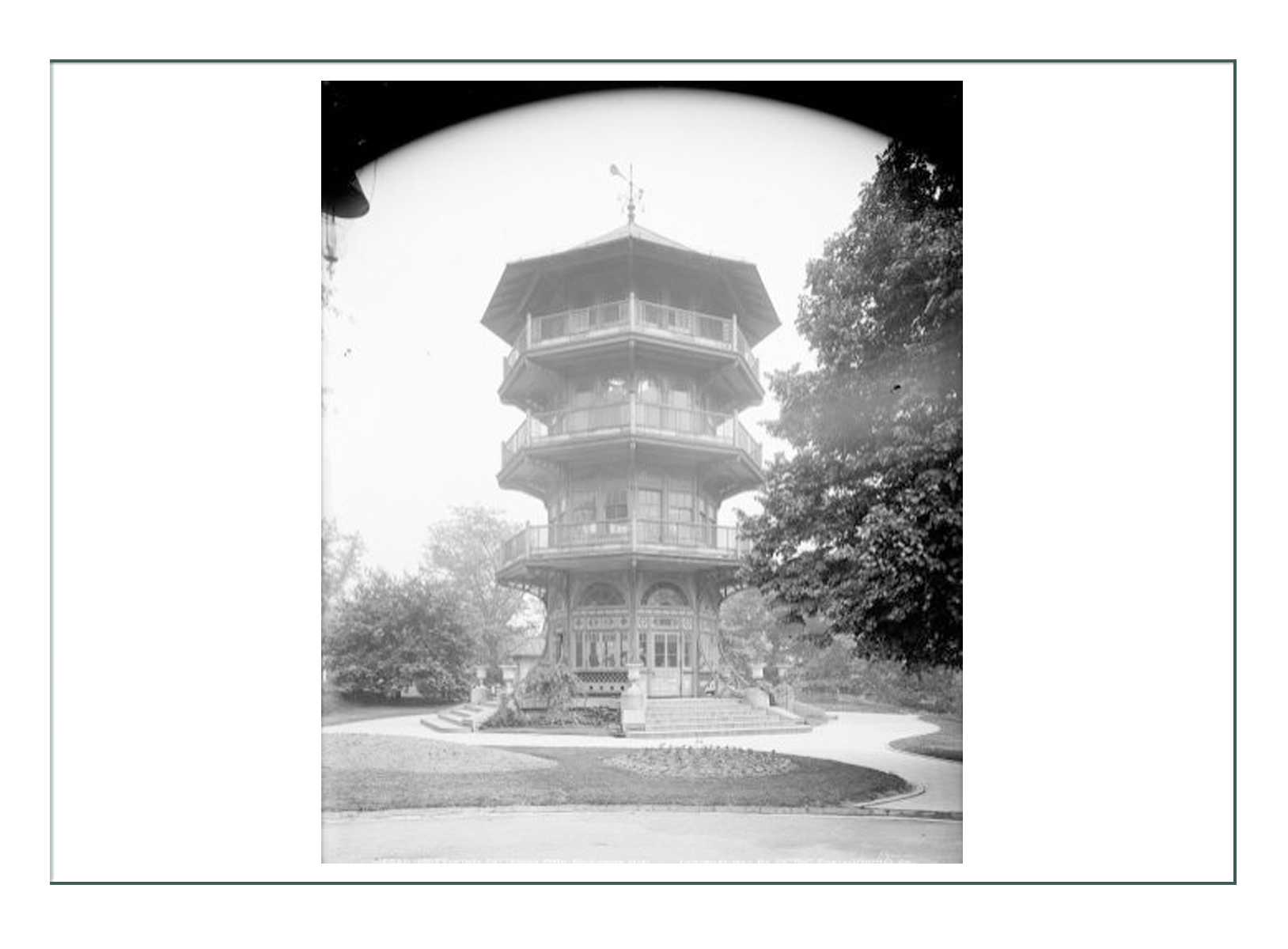

Hampton still exists today as a National Historic Place, run alongside U.S. National Parks. You can tour it with costumed interpreters (good potential employment for Anna). Built in 1783 and finished 1790 in the Georgian architectural style as were most eastern homes and buildings at the turn of that century, it was owned by the Ridgely family. The Ridgelys modelled it after the estates of English nobility with dozens of music rooms, parlors, sitting rooms, and such designed for entertaining visiting guests of notoriety, and hosting major social events.

An English guest visiting was impressed by the “cattle, sheep, horses.. superior for purposes of racing..” Mr. Ridgely was described as a “very gentell man”, with a daughter who cared for their slaves.

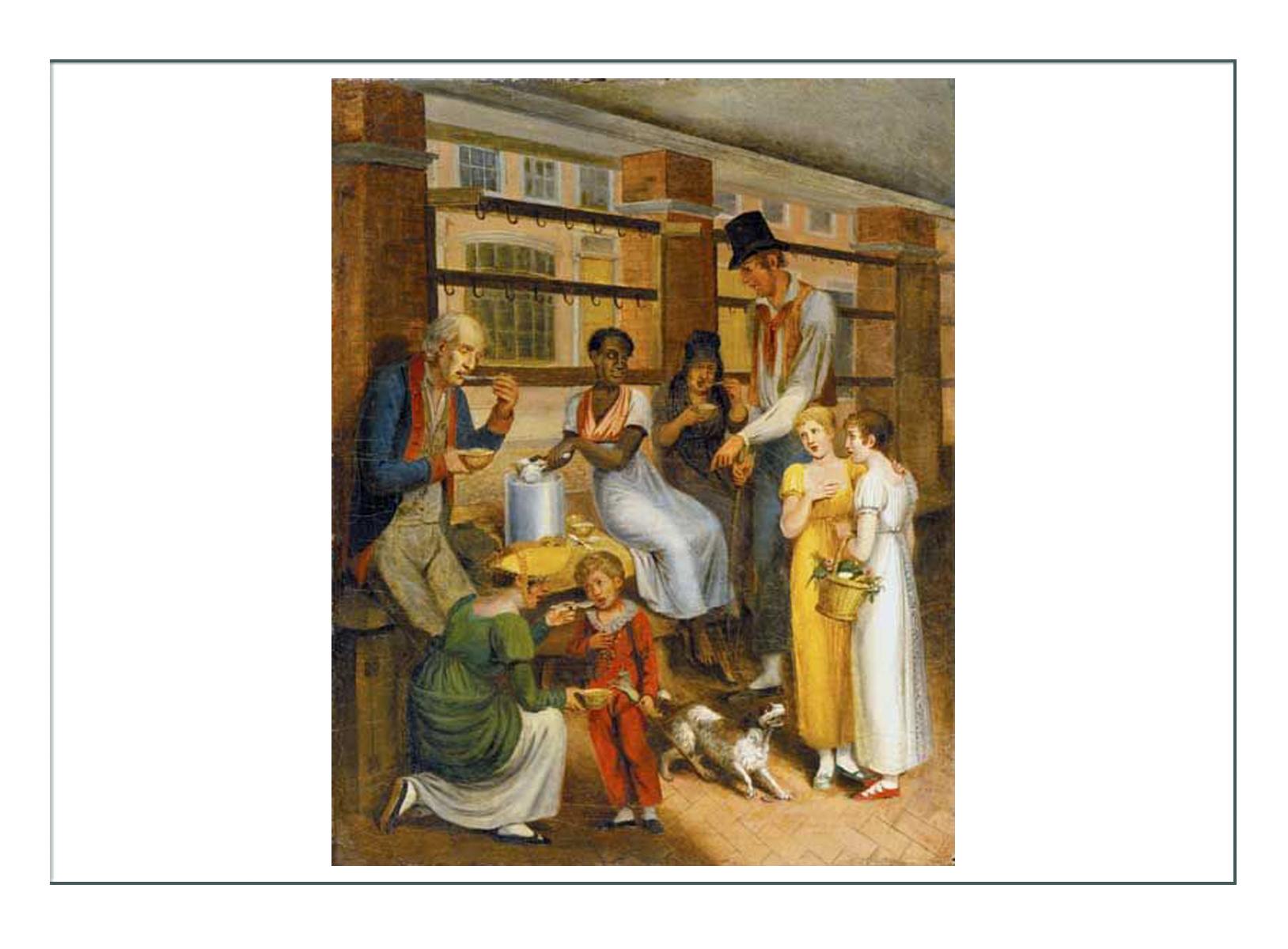

Servants & Slaves

Hampton is of note successful not only by the merits, knowledge, and efforts of its owners, but also by the sweat of its hundreds of indentured servants, and later in its history – purchased slaves. Hampton had entire villages for these, with cultures and rules of their own.

On the grounds were schools and greenhouses, kitchens, community centers, and outbuildings – all maintained by slave labor.

The Family

“Who’s Who” in ownership of the Hampton Estate is as follows:

- A relative of Lord Baltimore (of Baltimore’s namesake) bought the property in 1695 and farmed it. There were some stock barns, tobacco sheds, and small buildings on the land, but not the great estate yet.

- Colonel Charles Ridgely, who by the 1740’s had made his fortune with Northampton Furnace and Forge and by growing tobacco, bought the land in 1745

- By the late 1750’s, there was not only the tobacco farm, but also an ironworks, gristmills, apple orchards, and stone quarries on the property

- The Colonel and his son, Captain Charles Ridgely, who commanded a merchant ship, managed the property together with success in exporting raw goods and importing from England, until the Colonel’s death in 1772

- Captain Ridgely started to build the mansion and buildings in 1783, and finished in 1790. That year he died.

- The Captain’s heir was his nephew, Charles Carnan. There was some legal mess with the Captain’s wife, so Charles Carnan took the name Charles Carnan Ridgely, and retained ownership as per his uncle’s wishes

- Under Charles’ (the nephew’s) care, use of the property expanded to include irrigation, formal gardens, and an extensive horse breeding and training facility. Charles added products of marble and coal to his list of exports. He replaced tobacco with grain crops which could grow in the fields that were depleted by tobacco.

- By the 1820’s Hampton would be the largest estate in Maryland.

- The next in line to inherit would be Charle’s The Nephew’s son, John Ridgely with his wife, Eliza.

- After efforts through the years to use the estate for many businesses such as tea rooms, the property is now part of the United States National Parks and Historic Places.

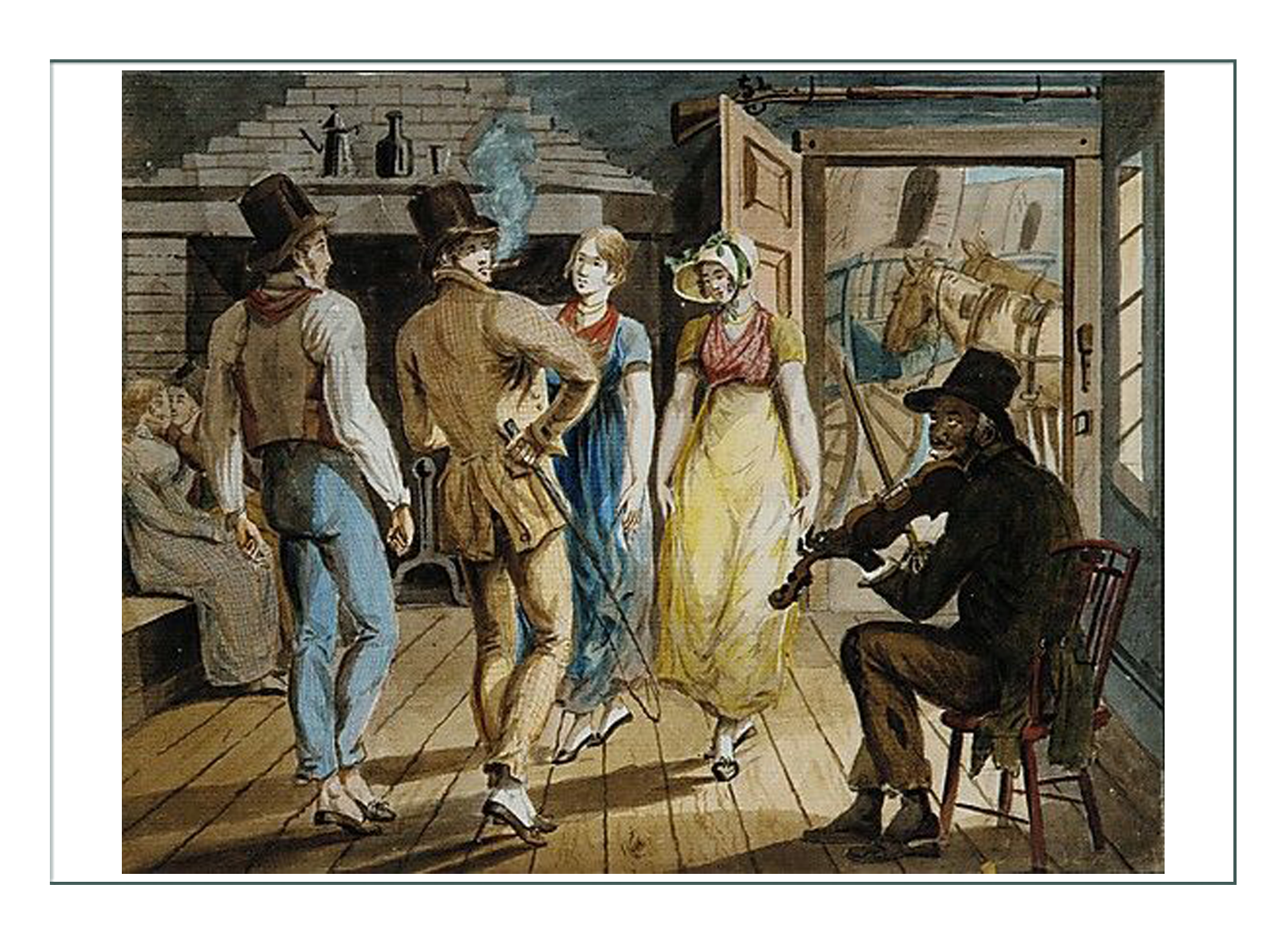

Hampton Lifestyle

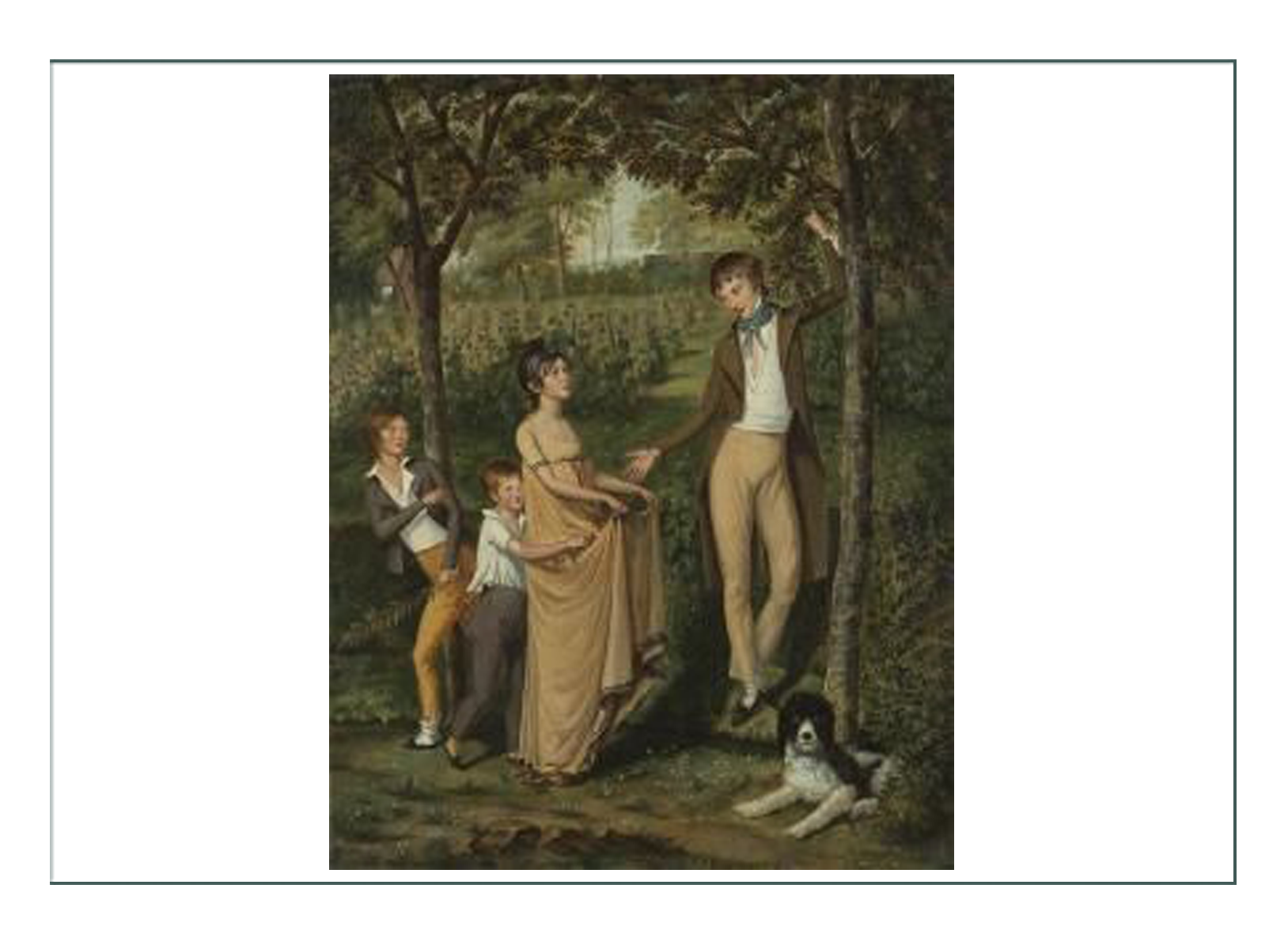

In attempt to describe the people, their activities, and therefore the character’s fashion, it is useful to note a few facts found in documents and stories about the Ridgely family in the 3 generations during the 1800-1805 era being depicted.

The Colonel and Captain having passed away only 10 years prior to depiction, would have ownership in the hands of Charles Carnan Ridgely, the 4th legal owner and 3rd generation of family to own it.

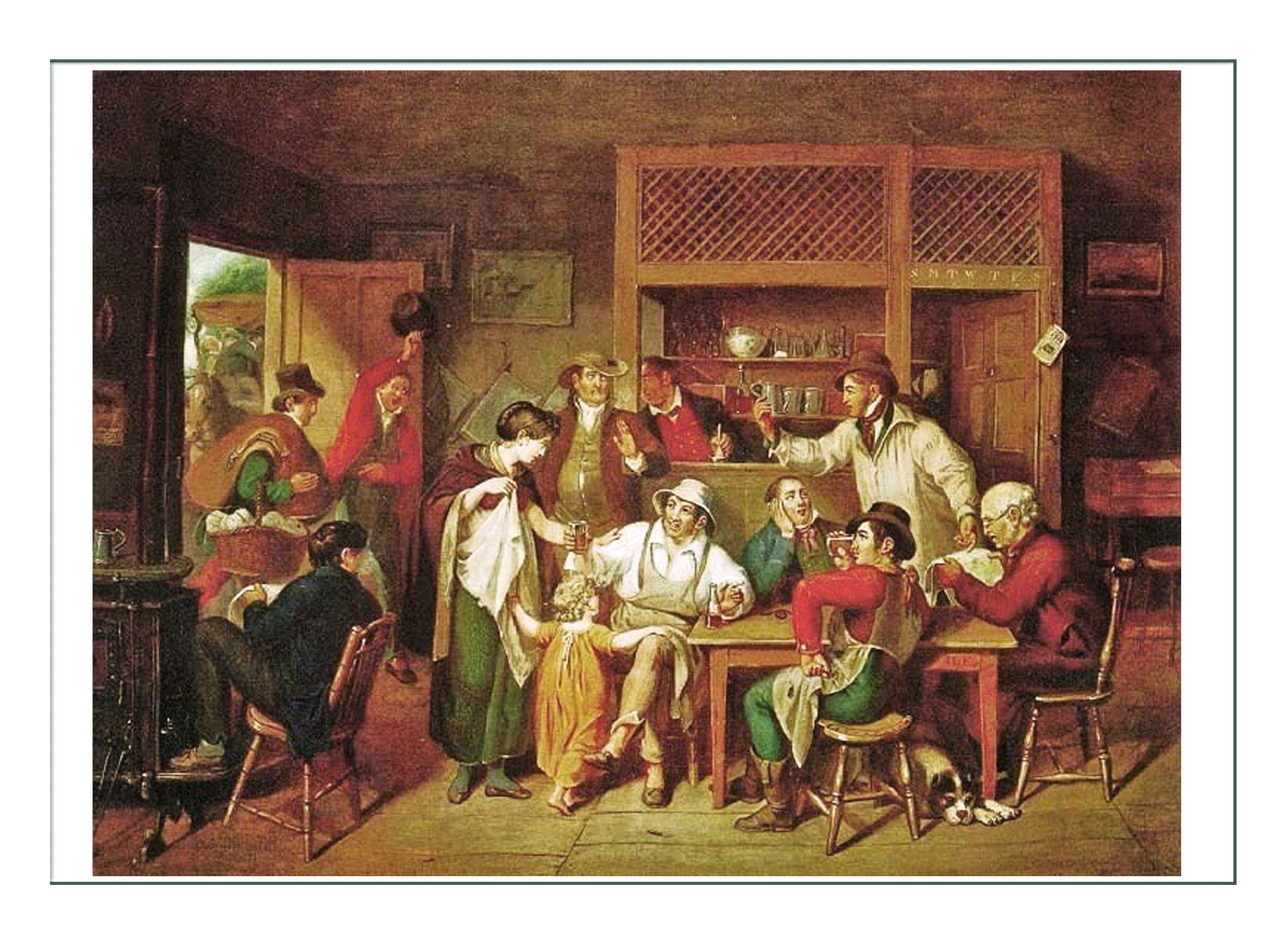

The Ridgelys only actually lived in the Hampton Mansion a small portion of the year. Most of the time was spent in their townhouse near the Baltimore Harbor so Mr. Ridgely could be near his many businesses and associates.

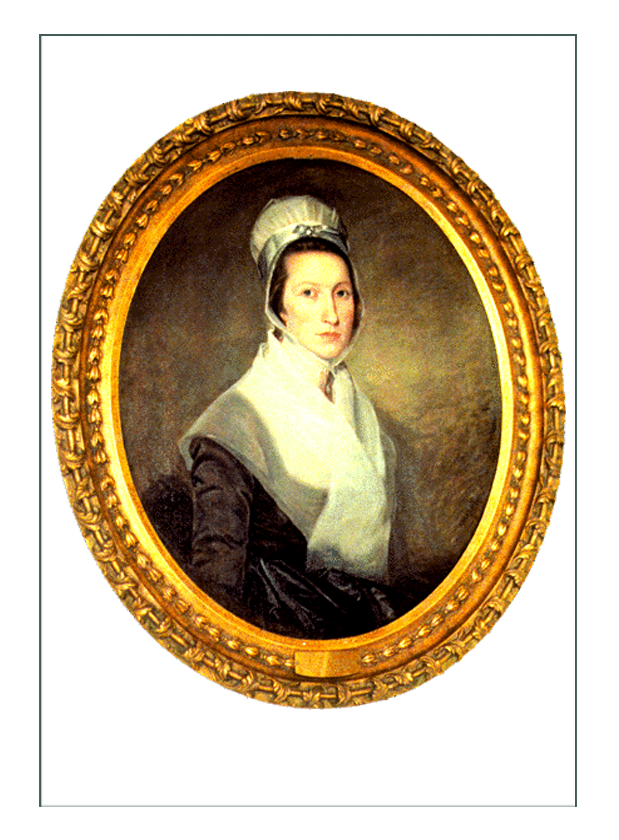

Charles married Priscilla Hill Dorsey in 1782 (while his uncle was still alive, but before the mansion was built) at Old Saint Paul’s Church in Baltimore. From this one can assume they were Catholic, a fact affirmed by their associations (and intermarriages of other family members) with the Carroll family, whose patron was the only Catholic to sign the Declaration of Independence. Carrollton Mansion being near the Ridgely townhouse in downtown Baltimore would have likely been an alternate spot for business and social interaction between the families.

Priscilla was the youngest sister of Charles’ uncle’s wife (the couple who had left the estate to him), Rebecca Dorsey. Rebecca had died childless. While Priscilla died only 22 years into their marriage (in 1814), she and Charles had 13 children. One daughter would become the First Lady of Maryland, and her eldest son John would continue to run the family businesses.

What they were like

Captain Charles and Rebecca (Dorsey) – 3rd owners (the partner son)

It was said Rebecca preferred a good prayer meeting to her husband’s drinking and gambling parties. He was a seafaring captain, with its associated stereotypes, as well as a merchant and foundry operator. Perhaps this had something to do with why they had no children.

The Captain had very poor handwriting and grammar, making him suspect that he had had very little formal education. Records show he was fond of a good, impromptu boxing or wrestling match wherever he traveled. He performed for wagers at county “fairs” and gatherings, impressing people with his physical strength and stamina.

The Ridgelys were known to house and host political gatherings of influential people of the Revolutionary and post war times.

While Rebecca was supposedly praying, The Captain was allegedly “borrowing” top quality male racehorses to breed to his mares. He claimed he always gave them back right away.

As typical of slave owners, Captain Ridgely was said to have been more interested in his finances, than in the welfare of those who earned them. He would leave the plight of the slaves to the next generations.

Charles and Priscilla – 4th owners (the Nephew)

Visitor records and letters describe the Charles and Priscilla as “gentell” people of “graces of nobile society”. They associated with England, and were considered the high society of Maryland.

Charles eventually entered politics after the War of 1812, and was Maryland’s 15th Governor from 1815-18. He was in the Maryland House of Delegates 1790-95, and the Senate 1796-1800. (This puts depiction right in the middle of his height of political and economic strength, at a time when his home was flourishing).

It was not always easy, but they appeared to have it so. Crop failures, financial difficulty, bad harvests, production problems, poor investments, and the huge costs of upkeeping the estate meant daily life could be very stressful.

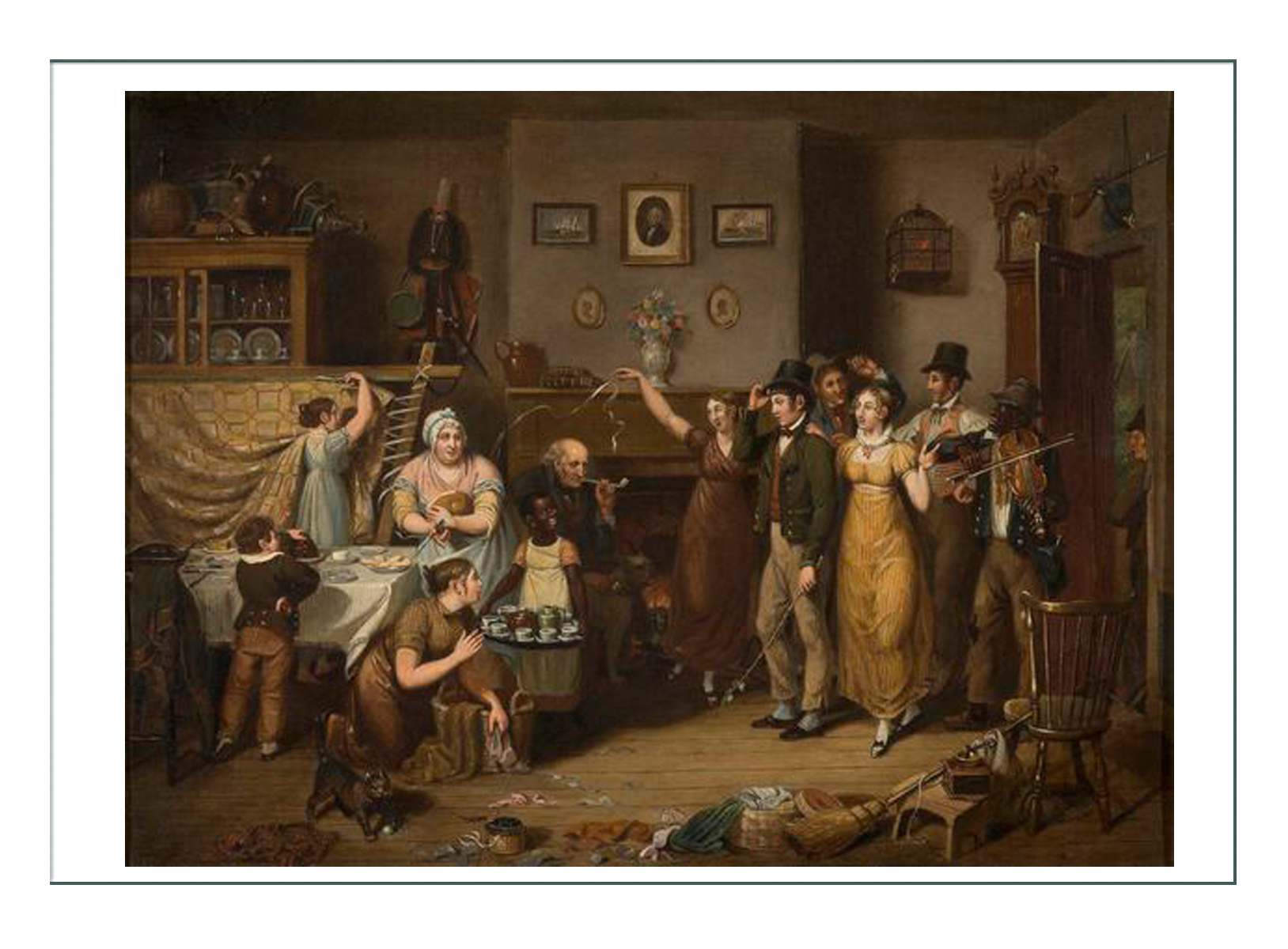

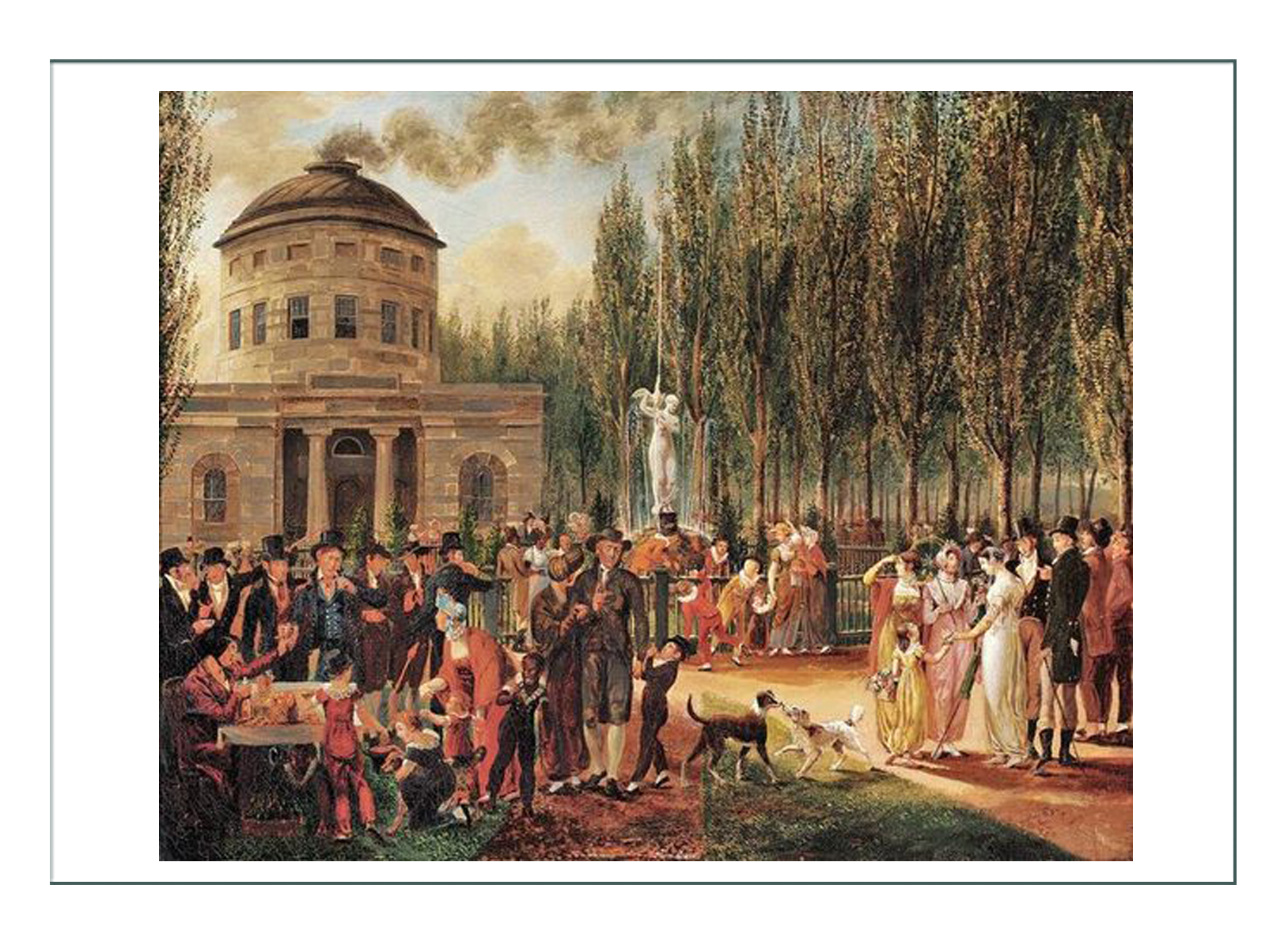

At the center of it also, was the focus on social status. The Charles and Priscilla Ridgelys were known for entertaining those of Baltimore and in government, as well as their overseas associates daily.

The Slave Issue

The Hampton operation was successful due to slaves, and they knew it. Unlike his uncle before him, Charles had compassion for the situation of his workers and their plight. He would have taught his children to respect and take care of them.

When Charles died in 1829, he had the largest holding of slaves in the state of Maryland at an estimate of 303. Through “manumission” is was able to free those under the age of 45, and those of value over $200, which amounted to about 105 slaves, notably women and children, who could legally be made free.

Those who were note permitted manumission, were given to Charles’ heirs to “take care of them”, although it is not clear whether that means the slaves were to take care of their owners, or the new generation of Ridgelys to take care of the slaves.

The next generation, John and Eliza

This caused quite a mess for Charles and Priscilla’s son John to inherit. With so many slaves gone, he needed a work force to run the estate – and quickly. He had a few of the “non-manumission” slaves of his own, and some from before his father’s death, but he needed a lot more.

John’s first activity as the new Hampton owner was to frantically buy slaves. Some of these were those that had been freed, and some were new. One can imagine the confusing coming and going among slaves and their families at this time. The primary issue was safety and control, as it was difficult keeping track.

Hampton became focused more on the farming and less on the iron production in John and Eliza’s era, although the family retained their merchant fleet and merchandising businesses worldwide.

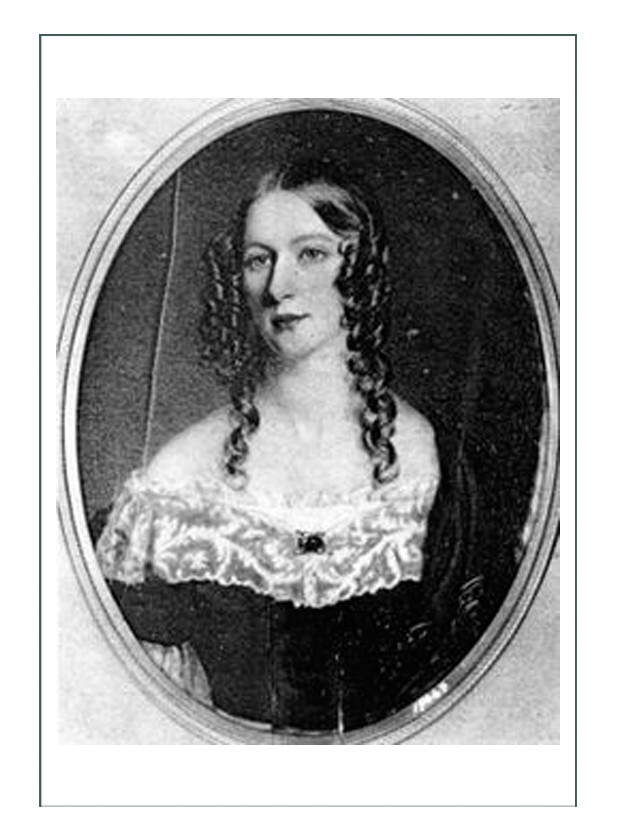

John’s wife Eliza enters the story during this time of change, as the daughter of a wealthy Baltimore wine merchant. She was an heiress, and would inherit Hampton alongside her husband, making Eliza Ridgely one of the most influential women of fashion in America at the time.

Entertainment and Fashion in early 1800’s Hampton

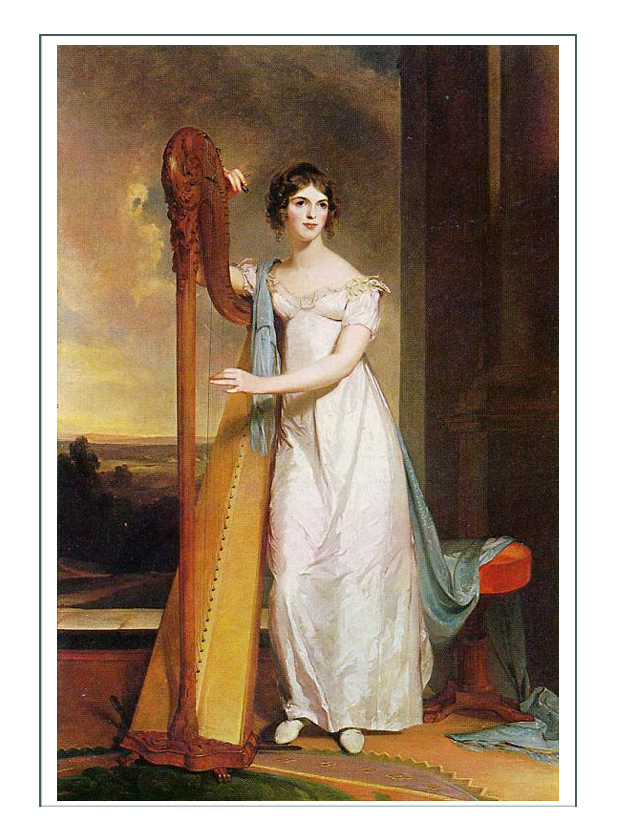

Under Eliza’s management, Hampton became the place for grand parties, political gatherings, and high society. In 1818 she was painted as “Lady with Harp” and gained fame.

The Great Hall was specifically designed by its original architects to host high society functions meant to impress the high status of its owners. Its walls saw such as Charles Carroll, signer of the Declaration of Independence, and later, the Marquis de Lafayette.

She was born a bit past the depiction era in 1803 (died 1867), but her influence on society is clear.

Eliza was a horticulturalist, and built the elaborate gardens. It is she who is responsible for the lush interiors of the house as restored today.

Heiress, traveler, and purveyor of world fashion, Eliza brought European influences back to the United States, and took American values to Europe. It is probable, though not documented, that there was association with Elizabeth Patterson of Baltimore who married Jerome Bonaparte, the youngest brother of Napoleon.

At this time, France was in the throes of the French Revolution, so trade and knowledge between the two elite ladies of Maryland, England, and France was most likely.

A nearby home of similar but not nearly so grand proportions was The Montpelier Estate by Ann Ridgely in 1781 and her husband “Colonel Thomas Snowden”. The two estates were used to host large gatherings of Patriots during Revolutionary War time. Almost every event was specifically designed for political purposes.

Family Businesses

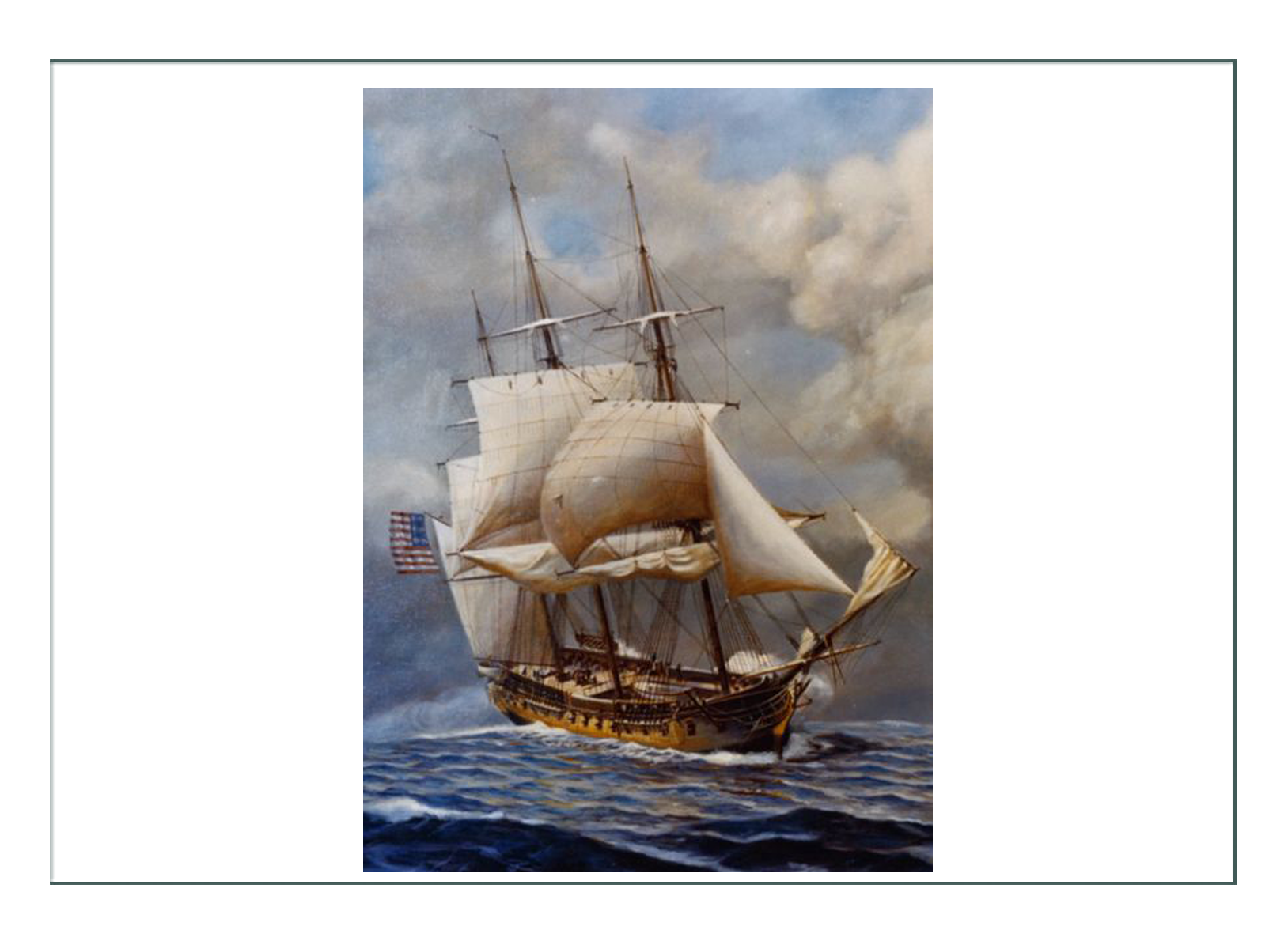

The success of the family started because of its ships. By the 1770’s, they owned a fleet of merchant ships which transported raw iron and cash crops from the US to Europe in exchange for finished goods. They got their elaborate furnishings for the estate manor in this way.

Seafaring family ships like the “Baltimore Town” carried raw foodstuffs and pig iron to England. Later, when the land was depleted by tobacco in the region, they switched to selling corn, wheat, and other grains.

On Hampton, 4 generations of Ridgelys bred and raced some of the top horses in the country, plus in the region they owned grain mills, textile mills, quarries, orchards, and had a general merchandising store in Baltimore.

A Profitable Place

Not only did was the Hampton estate a full production cattle and horse farm growing tobacco and grains, but it also provided all the elements for iron-making, it’s primary export: iron ore, limestone, timber for furnaces, and water power. By 1776, Maryland, thanks to Hampton, was the biggest iron producer in the Colonies.

The estate had coal mines and marble quarries. It also provided finished iron products, unique to the rest of the colonies who only sold raw iron. While predominately exports of household goods, the Ridgelys made a fortune during the War from the production of camp kettles, shot, cannons, and guns.

Profits from the War allowed them to buy up most of the land that was confiscated from the losing Loyalists, allowing the Ridgelys to further expand their holdings.

Character Emerges

It is into this interesting merging of a colonial past, an industrial future and political conflict and war in between that Anna’s character arises.

The daughter of a merchant upper class specializing in the manufacture of fleet ships, who not only manage the transportation of goods, but also of the raw and finished products to trade. She would have access before, during, and after all wars and conflicts to whatever she desired. She would be in the center of political intrigue, trade negotiations, and with complete knowledge of most types of businesses from breeding a horse and planting a seed, to selling the goods on the international market or from behind the counter of her own store.

She would understand and know the worlds of slaves and servants from an intimate, though possibly detached viewpoint. She would have knowledge and access to all the latest fashions and trends.

The only limitation of the character from being or doing whatever she wished, would be that she was a woman.

Not portraying an exact Ridgely character, Jacinta will draw from the real women of that family for inspiration. Virtually no documents, records, portraits, or stories exist of that generation of Ridgelys that would be young adults in 1805 exists today.

It is most likely Jacinta’s portrayal would be of one of the 13 children of “The Nephew” Charles Carnan Ridgely (1760-1829) and his wife Priscilla (1762-1814):

- Charles Ridgely (1783-1819)

- Henry

- Priscilla Hill Ridgely White (1796-1868)

- Eliza

- David Latimer Ridgelly (1798-1846)

- Sophia Gough Ridgely (1800-1828) married James Howard and had 2 boys and 2 girls in years 1821-1826

- Mary Pue (1802-1872) married Charles Worthington Dorsey and had 4 kids; her eldest named Priscilla Ridgely Dorsey in 1829 who carried on the historical records

- Charles Carnan, Jr

- Rebecca (Ridgely) Dorsey Hanson (1786-1837)

- Priscilla Gough Howard (1791-1841)

- John Carnan (1790-1867) was heir to the estate and he and his wife Eliza kept it going into the next generation

- Prudence (Ridgely) Howard (1791-1837) raised around all prominent people on the estate so she met George Howard, the son of former Governor of MD John E. Howard. They married December, 1811, and his parents gave them the estate “Waverly” near Woodstock, which is in today’s Howard County named for this family. They had 8 sons and 5 daughters; he followed his father as governor. 3 of their children died of “illness”

Prudence (Ridgely) Howard looks to have the piety of her grandmother, but had a lot of children and a happy marriage - Achsad (Ridgely) Carroll (1792-1841) married 3 times: John Carroll, Robert Holliday, and Daniel Channier

- Harriet (Ridgely) Chew (1803-1835)

The most likely for depiction would be Rebecca Dorsey (middle name for mother’s maiden name) (Ridgely) Hanson: born March 5, 1786, died September 7, 1837 at age 61. She would have been 19 years old in 1805

OR

Prudence Gough (Ridgely) Howard (1791-1847), although she would have been only 14 in 1805. Nothing more than birth and death records are known for either, although it is known Rebecca was born before Hampton Estate was completed, and Prudence was the first sibling born on the Estate.

Click here to go to Jacinta’s Historical Context page

Click here to go to Jacinta’s Fashion History Research page

Click here to go to Jacinta’s Design Development page

Click here to return to Jacinta’s main page with the FINAL PRODUCT