How World Fashion Ideals were Applied in the “New World”

How World Fashion Ideals were Applied in the “New World”

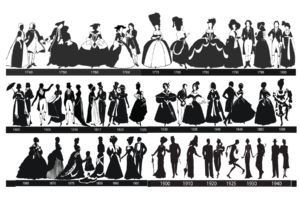

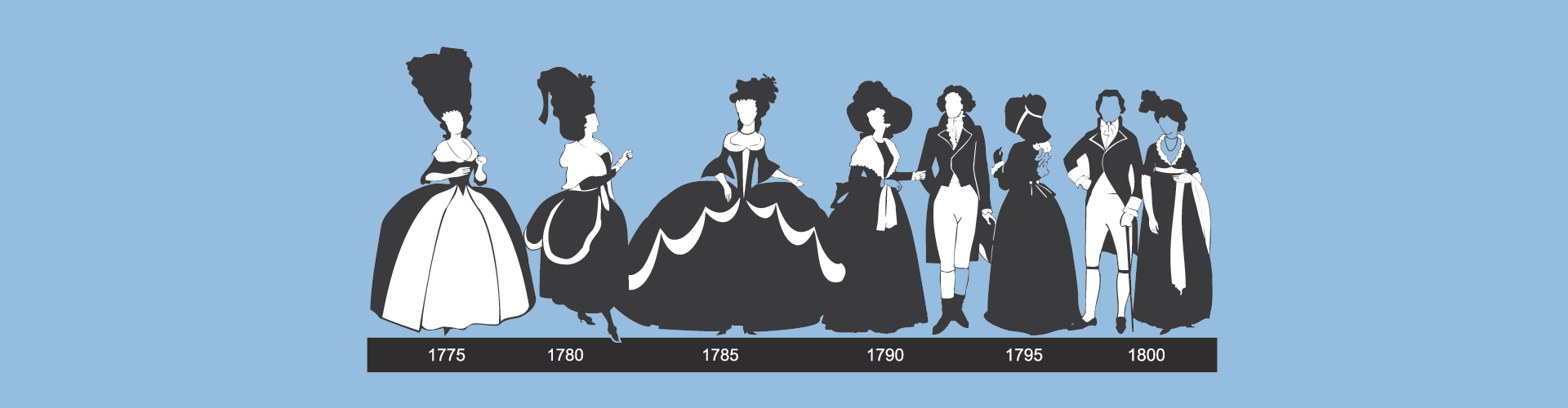

A silhouette is the recognizable shape of fashion as it changes

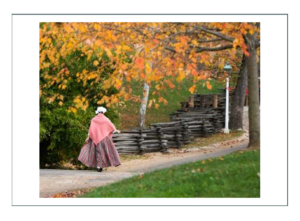

Fashion depends on what people know, can get, can do, afford, and want. A Silhouette is the recognizable shape of fashion as it changes. In the American Colonies, it was the Silhouette established by the Europeans, that was shaped and adjusted to fit the needs and tastes of women of the “New World” who had come from all over the world, bringing diverse and changing cultures and attitudes that would eventually merge into uniquely “American” fashion.

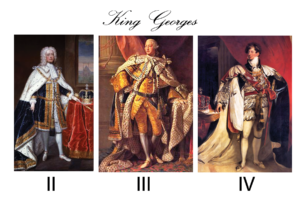

Most of the 18th century (years 1700-1800) was called the “Georgian Fashion Era” around the world, named after 3 King Georges of England. Because the United States was not yet created until after the Revolutionary War, the area that would become America was called the Colonies. When talking specifically about fashion in the geographical region that would become the United States, the “Georgian Era” was also called the “Colonial Fashion Era”.

The 1770-1790 approximate period covering the War was known as the “Late Colonial Fashion Period”. As with fashion today, there was no exact line that was crossed saying when one Era started and another began. Some women liked to keep their favorite clothing and wore it long after it went out of style, while others wanted to be right on top of what was new and fashionable.

The era was called “Georgian” around the world, but in what would become America, it was also called “Colonial”

STRONG AMERICA

STRONG AMERICA

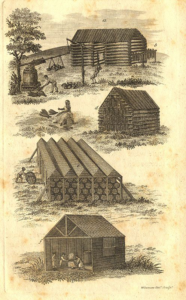

Tobacco was one of the key exports of the Colonies

The place we know as America was, during the Colonial Fashion Era, under the rule of England. The settled areas on the east coast were known as “colonies”. The colonies by the 1770’s had the benefits of being connected to a big country (England) with its manufactured goods, transportation, and access to trade. The colonies also had their own strong economies because they could trade raw goods like timber and ore plus agricultural products like wheat, corn, and tobacco for nice finished and manufactured things like furniture and clothing with countries around the world.

The new America at the start of the War had the highest per capita income in the world in 1776 because of a huge middle class made up of farmers and merchants. More people than in any other place in the world at the time could work really hard and rise (or fall) economically by their own efforts.

Colonists wanted to keep it that way, which became one of the reasons for the Revolutionary War because King George was involved with trade and production. Colonists thought they were doing fine without a king taking a share of their earnings through taxation and other government controls. The colonies wanted to be cut off from and to separate themselves from England and Europe politically and culturally and to set up their own country.

What would become America had become a “melting pot” of those who had settled already and those who were coming to find a new way of living away from the dictates of England. They had a new spirit of independence which focused on the individual’s ability to succeed or fail based on his own efforts. It was called the “Years of Abundance” for America and England. France was headed to a Revolution too, which would affect trade and fashion in America in the years after the American Revolution.

Inventions & Trade

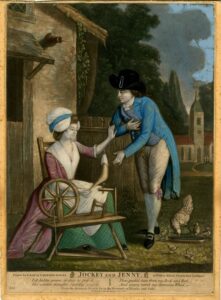

The “Spinning Jenny” patented in 1764 made it possible to mass produce fabrics, making them cheaper and easier to get

In the 1770’s, England dominated the world in the sale of wool, cotton, and silk, but the invention of steam for power and it’s improvement and growing use by the 1790’s changed the world forever. Steam engines had been used for pumping water and for boring holes for a few decades by the 1770’s, but the James Watt improvements would lead to use of steam in ships and textile manufacturing.

Steam drove ships which speeded up transportation of goods around the world so more countries could trade with each other. Steam would be used to run machines that could make things people previously had to make by hand.

When an English man invented the “Spinning Jenny” in 1764, it meant fabrics did not have to be made in the home, but could be made in a factory by paid workers. As better large scale mass production weaving systems for wool and linen were developed in England, it meant women didn’t have to stay home and make their own fabrics any more.

In 1752 Joseph Jacquard of France had invented the first “programmable” weaving loom which ran on punched cards would lead to today’s modern computer operated industrial and tech equipment.

(Left) The word “spinster” came from a word meaning a woman who lived her life preparing thread in her home. (Right) New inventions like the Jacquard weaving loom of 1752 would put many small home based businesses out of work

A very early type of machine had a big needle that could punch thick leather and wool fabric to make coats for fishermen and soldiers. That would evolve into the sewing machine we know today, which was first made small and gentle enough to be used in homes by women in the 1860’s. New methods of spinning, cutting, and making things like lace were developed to speed up the processes of making trims and decorations and specialty fabrics too.

When people manufactured complete clothing or textiles in their homes from start to finish to sell, it was called “cottage industry”. With the invention of new machines, people no longer made the entire garment, but would make a part of it such as the sleeve on a shirt. One person would make a lot of sleeves in their home, and take them to town where people in a factory would put the shirt together.

Factories changed the way clothing was made, sold, and distributed throughout the world. It meant the Colonists could actually get cheaper clothing by importing it from big cities overseas. Unlike how people picture these early Americans as spinning and weaving all day and night in their homes to make clothes, most on the eastern Colonies were buying and wearing goods from England and other countries over the ocean. Only the really deeply rural or western colonists had to make all their own clothes.

The ships not only carried trade goods, clothing, and equipment, but they also carried information. An increase in trade and invention meant and more ideas in the Colonies.

Fabrics & Dyes

Cotton broadcloth is used today for “no iron” shirts

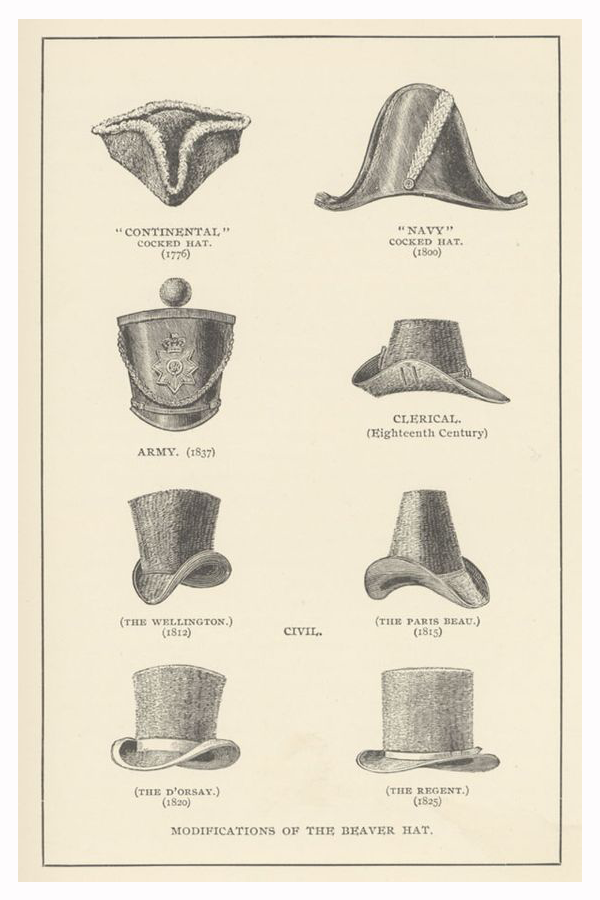

Fabrics were becoming cheap and available in Europe with the creation of factories, and these items were quickly shipped to the Colonies. The French and the English had led fashion trends for the world for centuries, but in 1775, Colonists started to give ideas to the Europeans. News of the North American West with its beavers, furs, and backwoodsmen affected European fashion.

Beaver fur from North America became a favorite of the French & English who wore it in their wars like this French military bicorne beaver hat (left): Napoleon Bonaparte’s signature bicorne (right) was shot off his head in 1807 during a battle with Russia

Beaver fur from North America became a favorite of the French & English who wore it in their wars like this French military bicorne beaver hat (left): Napoleon Bonaparte’s signature bicorne (right) was shot off his head in 1807 during a battle with Russia

Colonials in places far away from the seaport cities used more simple, natural, and plain fabrics and designs than people on the east coast. Even with the vast trade systems from around the world, these remote settlers couldn’t get a lot of the heavily ornamented or fancy things from across the ocean into the backwoods. The simpler clothing which focused on “function first” suited their lifestyles.

“Broadcloth” became the “every day” fabric across new America. It was a simple very tight weave with a smooth and flat surface that was durable and easy to sew. It could be made of different materials that could be found in the Colonies such as flax or wool. It was strong enough to be used over and over in remaking garments.

Cotton clothing & fabric had to be brought to the Colonies on specially outfitted cotton ships before 1800

Cotton clothing & fabric had to be brought to the Colonies on specially outfitted cotton ships before 1800

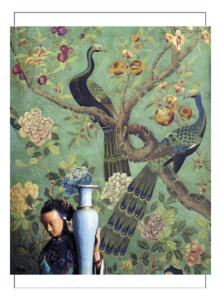

There were English ships coming and going between India and the Colonies, so Colonial women could get lovely fabrics. Trade with some Asian countries and places like Holland and Spain made other special fabrics, laces, trims, and finished clothing available to those who could afford them. China and its lovely silk fabrics was not yet open to trade with the Colonies.

People who had money got silks or cotton from India, because the Colonies did not grow or process much cotton yet. The special worm that spun silk would not grow on North America. India had that special silk worm in a special area that made them the only source of that kind of silk in the world.

18th century silk fabric from India was much thicker and lighter in weight than anything we have today. It made the shape of the gowns stiffer so they could be very big but not too heavy. The 1770’s silks made a special sound when a woman walked in her skirts that was notable of the Era.

India, which was under British rule in the 1770’s, also had special dye processes for cotton and provided the many beautiful floral designs that are now notable of the Colonial Era.

Trade with Indian made possible the import of beautiful florals printed on cotton and silk available to the Colonists. These designs are now notable of the era. Patterns became more delicate and detailed as printing processes & fabrics improved

The new America would become the leading producer of cotton by 1820, but in the late 1700’s, while it was being grown on southern plantations, it was still experimental there. There were few processing plants, so the making the cotton into fabric in the Colonies was costly. Most 1770’s Colonial homemade clothing was therefore made of wool, flax, or linen which could be grown locally.

The indigo plant which grew naturally in Eastern Asia, India, and Peru, was transplanted to England & used for the favorite blue/green color of the Colonial Fashion Era. By the 1860’s it was produced in America for Civil War uniforms

Colonial people could buy nice fabrics from places all over Europe like England, Holland, Portugal, Spain, and France. These countries had their own unique materials, designs, methods, and dyes such as the making of “plaids” in Scotland that the Colonists bought.

European countries, and especially England, had brought the artistic, chemical, and manufacturing methods from other places like the West Indies and Africa. They were trying to grow plants to make special dyes with some success, but historians say their art and science was never quite as good as that in the places of the plant or art’s origin.

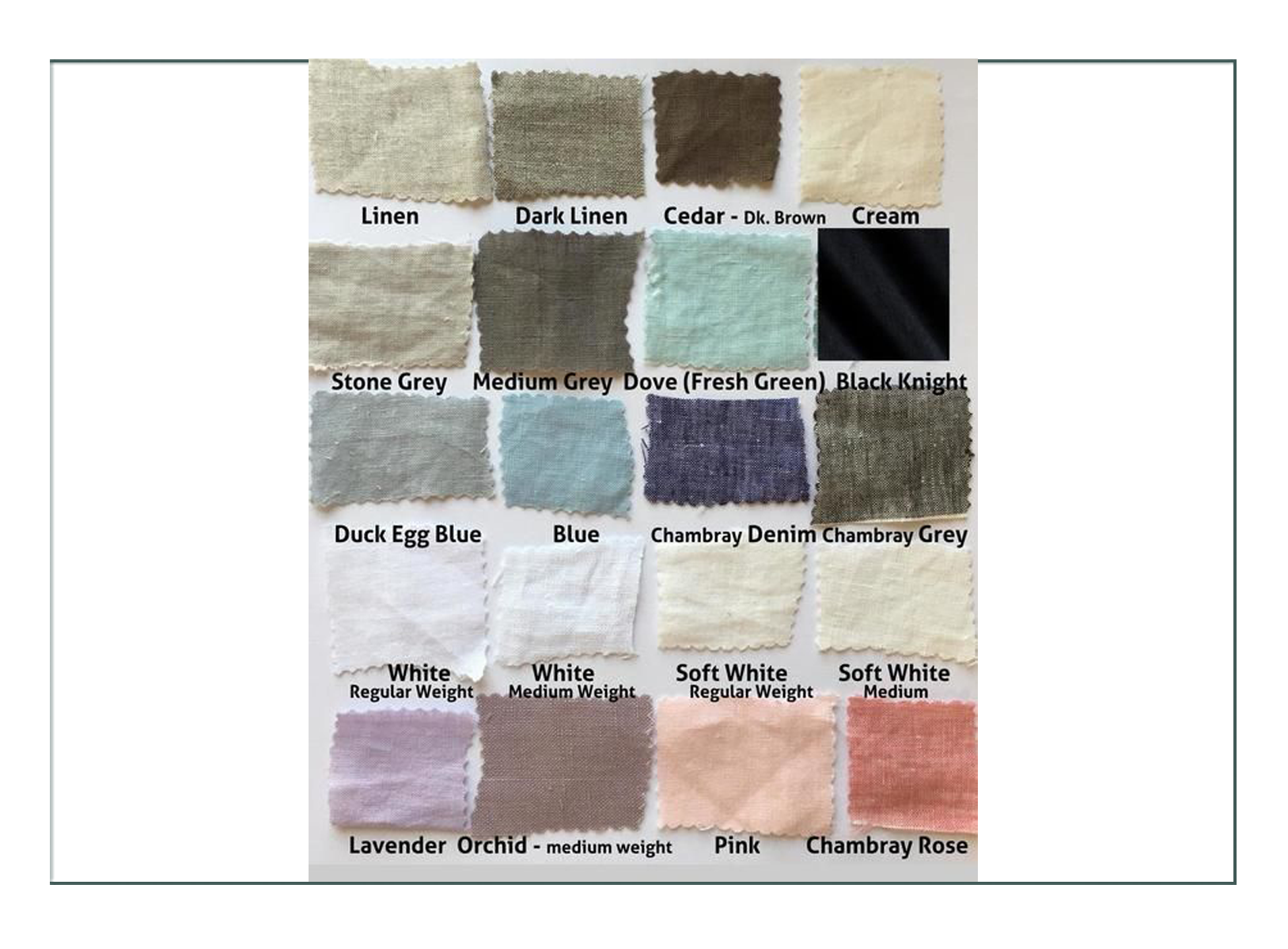

Colors from natural sources like berries and bark dyed onto natural fabrics like these linen samples are subdued and look like nature

Dyes produced in the Colonies were from natural sources too, like berries for pinks and blues. Sticks, twigs, walnuts, and nutshells made browns. Many plants, mosses, and bugs were used to make greens. There was a favorite orange/red color that came from an insect, although it had to come on a ship from an island so was hard to get.

“Red Dye No. 2” which is used in food today comes from a female insect which lives on cactus in southern areas of today’s U.S. and Mexico. It has been a favorite dye for orange/reds for centuries. (Right: botanicals like the center of the saffron flower are used innovatively, in this case for yellow/gold/oranges)

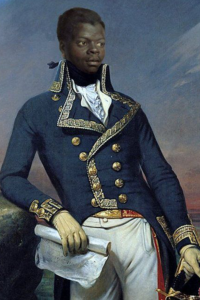

Indigo, which made the deep blue/greens of military coats (like blue jeans) was being grown in the south with some success, although it didn’t flourish in the Colonies. The use of North American indigo was widespread, and that blue would be one of the favorites 100 years later during the Civil War.

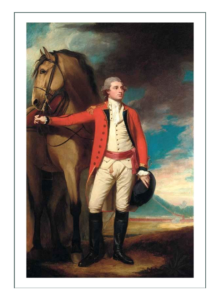

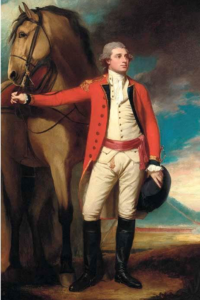

The actual “Redcoat” military uniform of the British Counsel to America 1794 (left), & Major James Harelty’s at about the same time; both dyed from the cochineal insect

The bright reds and pinks were a favorite of both men and women colonists, and the British used the insect dye to make their military uniform “Redcoats”. Intense blue or purple other than the blue/green or purple/pink types of blues could only be found from rare sources outside of the Colonies, so only the very rich and European royalty wore certain blues and purples.

Only Estruscan royalty (left) wore the bright purple that is still reserved for Royals today like Queen Elizabeth II of England (right)

The favorite colors of Colonial women were the many pinks, browns, and a blue-green called “teal” plus the indigo blue. Synthetic dyes would not be invented until the 1850’s when a man accidentally invented “mauveine” while trying to find a cure for malaria. With a huge fashion industry in the 1870’s and a big interest in science at that time, most of the really bright and intense colors you see today were invented around that time, 100 years after the Revolutionary War. It was rare to have bright or intense colors in 1776 unless you were royalty.

Even main streets in big cities during the 1770’s were muddy like this modern day Colonial Williamsburg living history site

Fabrics

Linen

The fabric of choice for every day women of the 1770’s was linen. Linen acts much like cotton, but it is stiffer and has a shiny side to it, a rough feel, and has a more open weave. Both cotton and linen let air flow in and out, so they are very comfortable to wear and work in, and easy to clean.

People did not know about germs yet in the 1770’s. It was only in the Late Colonial/Georgian period people figured out they should wash their clothes and themselves regularly to prevent sickness. A new type of detergent similar to today’s bleach was being used. Because it turned everything white, white became the most popular color for things that would be worn a lot or touch the ground.

Roads in the Colonies were muddy. Even in dry places, dust would get dresses very dirty. Women worked hard and had no air conditioners or electric fans. Even women of wealth and royalty did work, and they would get sweaty. The natural fabrics and the design of their clothes kept them comfortable between washings. Only the bottom most layers would get sweaty and have to be cleaned often.

Boys, Girls, & Families

Phillis Wheatley was a young woman in the 1770’s when she became famous for her poems

When you decide what to wear, you are really making the decision based on three things: what will I be doing (function), what do I have or what can I get (economy), and what do I like/want (fashion)? What children in Colonial America wore, depended a lot on two things: what they were doing and what could they get or make.

Play

Hoops or “Hoops and Graces” were a favorite game for Colonial children

Boys and girls in the Colonies did not have an easy life. Most of their time was spent working. When they did have a few minutes to play they had to do it with things they could find, as most could not afford toys, have time to make them, or be able to buy them somewhere. Stores and factories were mostly in larger towns which were mostly along the eastern seacoast. People living on farms or outlying areas didn’t go to town very often, so there was not much opportunity to buy toys or games near home.

Games like “Jacob’s Ladder” (left) were imported on ships, but most children made their own toys like cornhusk dolls made of things laying around the farm plus scraps of fabric (right)

If parents had some money they could order from a store in town that would bring in the item on a ship from England. Dolls, tea sets, metal figures, and board games were often available , but if there was something like a doll house, the parents usually made it. That was rare since the parents worked most of the time too.

The childrens’ game of “Rounders” was adapted by adults to become “Baseball” as this 1760 paper article about sport showed

Children made toys out of things like the metal rings off of old barrels which they rolled around. They used string for hand games like “cat’s cradle” and pebbles for hopscotch. Children were competitive in throwing horseshoes and a game called “Rounders” which was an early version of baseball.

School

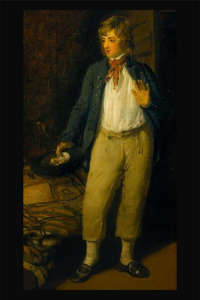

Children in school in 1790 are shown wearing the same clothes as their parents, but a little more loose and comfortable

Because Colony leaders felt educating children would produce good citizens, almost all children were educated in some way, although that didn’t always mean in a school room. Many were taught at home either with just a parent or with a group of children from the farm or plantation under the instruction of a family member selected by all the families involved. Communities required parents who were home schooling to report their children’s learning and progress regularly to make sure children were being taught with the values of the Colony.

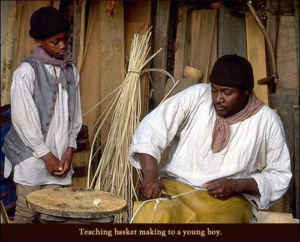

Historical Interpreter boy apprentice (left) learns how to weave baskets from a skilled craftsman. The skilled trades like carpentry were of great value, and apprenticeship to cabinetmaking (right) was a well respected job for a young man

Many boys had apprenticeships where they would work alongside a specific trade such as blacksmithing weaving, basketmaking, tailoring, innkeeping, or whatever their father was doing to learn it by doing it. Apprenticeships started as early as 6 years old, though most typically a boy was 14 when he started.

Some boys with wealthy fathers were sent away to college at the age of 11. The girls stayed home to help their mothers and rarely went away to school, although some went to live with relatives to learn.

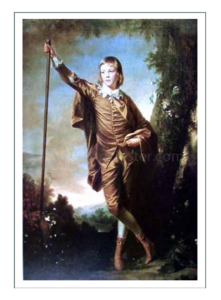

A Colonial boy from South Carolina, dressed in finery the same as his father would wear

Colleges were larger places where the boys stayed and lived full time and came home only on breaks, much the same as college today but with much younger students. Boys and girls who went to a lower level school outside of the home went to one where all the children were taught in one room in one building by one teacher.

The Nathan Hale one room school was originally located in East Haddam, New London, Connecticut in the New England Colonies, but is getting ready to move a 7th time as it sits next to a parking garage today. It was named after one of America’s Founders, Nathan Hale, who taught in that building from when it was built in 1773 until the War started in 1775-76

In the New England Colonies which were on the northern coast, most people lived near or in towns. There were many schools and school buildings located near population centers where there were the most children. The parents built and paid for the schools themselves, and paid for their children to attend by supplying firewood, food, or supplies as well as money for upkeep on the building and to pay the teacher.

Simply called “The College”, this was built 1695-1700 in the Virginia Colonies and the inside was burned down 3 times (twice during the War Between the States), and was eventually named “The Wren Building” after Christopher Wren, architect in 1931

In the Middle Colonies, schools were part of the churches and based on religious teachings, and if you couldn’t pay for the school, you could not send your child. Since it was a very agricultural area, school was in or out of session depending on planting and harvesting cycles.

In the Southern Colonies there were few people living near each other, and farms and plantations were spaced far apart. Some southern children were taught at home with a parent or an assigned family member or hired tutor. Some from wealthy families or with family in England were sent to live across the ocean to go to school.

Most children went to a school on the plantation with other children from the area. Many southern children did not have formal education, but learned about religious beliefs, morals, and values through their home based organizations such as churches or religious societies.

A Hornbook was often the only book a student had

Colonial schools had few books or paper, so most of what the children learned was from memorization. The Bible and the New England Primer were about the only books used in class. Some had a “hornbook” which was one piece of paper with the alphabet, numbers, and a prayer that was attached to a piece of wood and covered with a see through piece of cow’s horn. It had a string they could wear it around their necks.

Work

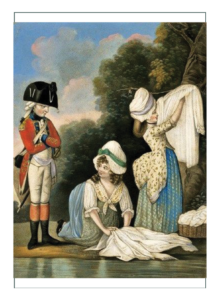

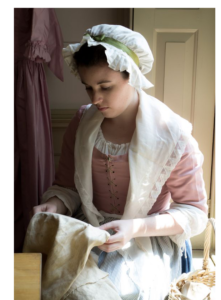

A girl interpreter helps with the laundry at Williamsburg Historic Site

What children did for chores and tasks was different depending on where they lived in the Colonies. Because one in every four children in the mid-1770’s in a family died before they reached adulthood from things such as the diseases cholera and malaria, they had to grow up quickly.

Many families lived on farms in agricultural areas, so there were animals to take care of. Children were in charge of feeding and watering all the animals. They milked cows and collected eggs from chickens. It was their job to gather fruits and vegetables from the gardens. Even very young children helped to shell corn by removing the kernels from the cob.

Boys also helped their fathers hunt for birds and animals or fish to provide the meat they ate every day. They helped plant and harvest crops. Boys who lived in the city built furniture, sold things at market, and made repairs around the home.

Girls who were indentured servants or slaves were assigned special jobs suitable to their age and skills, and often worked alongside their working mothers until sold, transferred, and in some cases married when they would work where their husbands were

Girls were in charge of sweeping, cooking, knitting, and sewing. They would shear the sheep to cut the wool off, and then spin it into thread. They would use that thread to make clothing and blankets.

Girls made soap and candles too, and they did all this while watching, guiding, and teaching younger children. Girls learned to sew and run a household at a very young age, and were able to run the farm as well as house, plus do any special work their mothers might teach them such as caring for the sick.

Colonial girls did farm work, house work, made items, taught children, helped their mothers, and also worked for other people

Daughters of women who were indentured servants or slaves worked alongside their mothers or had special jobs. Many girls had jobs outside their own homes doing the same chores they had learned at home like laundry, cooking, cleaning, and even teaching or caring for younger children of employers.

They worked in houses and shops in towns, cities, farms, and plantations and were a key to the successful economy of the time as they provided both special skills and the labor necessary to produce and maintain the many small things that made the Colonies successful, comfortable, and profitable.

The Family

Girl historic interpreters demonstrate how sisters worked alongside each other at school and work. Young siblings served in the Continental Army as these modern interpreters demonstrate

In a family with great wealth and privilege the children did not do farm work or labor, but those were rare as most colonial families were not rich and almost every family of every class had 7 to 10 children to take care of. The parents themselves did most of the child care work with the help of grandparents and other family members. Many of those 10 children, however, were not always at home. At an early age they were often sent away to apprentice, or started their own families and moved out. Girls were trained to be married and to run their own households from as early as age 13.

Today’s parents would be horrified to give a large gun to an 8 year old, to ask him to fill up a huge barrel of water from a rushing river, or to defend the sheep from a wild animal. Parents did not watch over their children while they did these things, although older brothers and sisters would watch out for the little ones. It was considered part of their job in the family to know the rules and how to keep safe.

Colonial parents considered the most important lessons they could teach children were their religious beliefs

Parents made sure before a child left home for whatever reason that the child knew very well about the religious beliefs and understood about morals and the consequences of one’s actions. Children had to grow up fast, and what may seem harsh parenting today was necessary to keep them alive.

Whether young or old, each person in a family had specific role

All members of a family had a role to play and it was important to the survival of the family that each did their specific jobs to the best of their ability. The main idea for raising children was to “love but not pamper”. Now and then a parent would make a small whistle or thoughtful gesture to each child which showed their “great love and nurturing nature”.

Colonial families for the most part lived geographically closely to each other and helped each other. Extended members like grandparents were important to the survival and success of the family as a whole. Older generations made sure the young ones were learning the lessons they needed to be “good citizens” for the future.

Busy People

No matter class, age, or occupation, Colonials were busy then – and now! (re-enactors, interpreters, and extant portraits below):

Europeans Followed Colonists

Europeans Followed Colonists

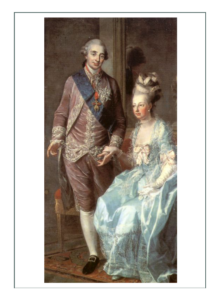

1776 American militia man (left); King George III at the same time (right)

There were philosophers in Europe who were teaching people to “simplify”, and the informal American styles and use of soft, comfortable to wear, natural fabrics appealed to people of England, France, Spain, and other countries. Because it was a time of abundance in both Europe and the Colonies, people had the luxury to think about what they were wearing, and to make choices.

The English had more leisure time than Colonists, and were generally outdoors more than other Europeans at the time. The English culture valued open spaces and physical activity, and was still predominantly agricultural.

Simple walking clothing for Colonial (left), Englishwoman (center), Frenchwoman (right) illustrates how the French took a simple concept and made it complicated

French culture focused on indoor activities and Court life. English and French clothes reflected each one’s lifestyles of indoors or out. The French, however, were peeking at the English, who were peeking at the Colonists. The French especially liked the simple and rural type of clothing the English and Colonists were wearing.

Europeans gave the Colonial ideas of simplicity with natural colors, natural fabrics, and “plainness” to their fashion designers to make them into new designs. The new French fashions of the mid 1770’s had the same shape, colors, and fabrics as the Colonist’s, but the French added fancy work, ornaments, trims, and “flashy” details. The French “Colonial Fashion” was not much like the Colonial’s “Colonial Fashion” by the time they got done.

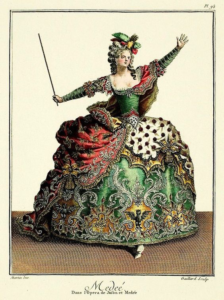

French opera costume sketch 1774-75, supposedly based on Colonial fashion, strayed far from it

Style of the 1770’s would become simpler by the 1790’s, led by French designers who were peeking at the comfortable clothes of working people in the Colonies

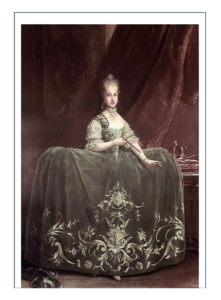

“Regular people” around the world, those who worked or ran businesses or farmed and who were not royalty, were wearing more simple and comfortable clothes constructed from easier to make and cheaper to get fabrics. Through the 1770’s and into the 1790’s the French continued to build fashion to become excessive in design under the example of French Queen Marie Antoinette.

Creole women (right) embraced the loose, cool, cotton Gaulle style of Marie Antoinette of France(2 to left) in the Dominican by the 1790’s just because it made sense

When Marie finally embraced a new, soft, and feminine style called “Gaulle”, the French would swing back the other way to make the next fashion era, The “Regency Era” very simple. All the ornament and fuss of the “Georgian/Colonial Era” would disappear from the 1790’s to the 1890’s.

Colonists Followed Europeans

French King Louis XVI & Marie Antoinette his queen (left); same yet very different from a real gown from 1776 America

In the 1770’s, the French demanded their royalty must look very different from “regular people”, and the French King wanted those who had money to spend it all on French fashion which was made from French fabric, lace, trims, and notions. In 1775 the French Queen Marie Antoinette wore the highest hair ever on top of her head. Another woman, a friend of the King, Madame Pompadour, wore a sailing ship over a tall wig.

Madame Pompadour wore a ship on her head

Both women’s dresses became so wide and so huge they couldn’t fit through doors. Fashion dictated that breasts be pushed up and necklines go way down. There were never too many tassles, ruffles, fringes, laces, plumes, or artificial flowers for the French. Even the men in French Court wore elaborate wigs and had clothing covered in fancy trims and embroidery.

French fashion leaders, Queen Marie Antoinette (left), and Madame Pompadour (right) in Court ensembles

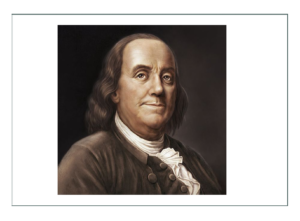

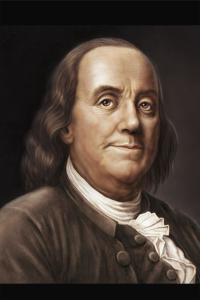

By the end of the Revolutionary War, however, with a change in power in France, the crazy French court costumes were replaced with very natural and very simple looks. Even hair, after Benjamin Franklin of America went to the French Court in his natural hair after forgetting his wig, became natural again. Colonists, by then calling themselves Americans, had been copying French fashion. The Americans along with the French and English pulled back to simpler and more comfortable styles in the 1790’s.

Benjamin Franklin (left) in natural hair 1767 & same year in his wig at Court in London, England (right)

Many Americans, particularly those with ties to the English before, during, and after the War, still wore the elaborate styles through the 1770’s. Women of middle and high class status continued to wear the elaborate French Court styles long past when they had gone out of fashion in Europe, although they backed off a bit from what the Queen of France was wearing.

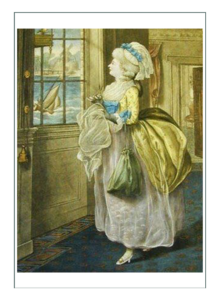

Queen Charlotte of England (left), Martha Jefferson late 1790’s, and First Lady Martha Washington (right) at age 58 in the mid 1770’s

Georgian & Colonial Fashion Specifics as Applied in the “New World”

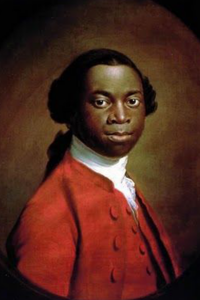

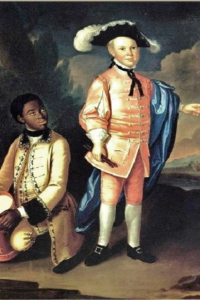

Colonial clothing was known for its great diversity because there were people from royal governors to indentured servants and slaves and everyone in between living in what would become the United States before, during, and after the Revolutionary War. In the 1770’s upper classes kept up to date on what was in fashion in England and France from imported garments, letters, news from travelers, and dressmakers or tailors moving into the region.

Re-enactors at Colonial Williamsburg depict specific people including artisans, trades people, and those of all classes. It was a time of class distinction strictly directing what people wore and how they wore it.

Re-enactors at Colonial Williamsburg depict specific people including artisans, trades people, and those of all classes. It was a time of class distinction strictly directing what people wore and how they wore it.

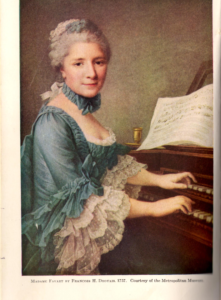

Women and girls living in the Colonies got most of their ideas on what to wear from England. The English got their ideas from France. The French had fashion designers and royalty who came up with the ideas. French Court fashion led the way in determining what women around the world would wear. Regular women would take the ideas of French royalty, and make them into things they could afford, make, and wear while doing whatever it was they did.

People learned what was fashionable through letters, prints, and from travelers

A wealthy planter’s daughter in Virginia in 1775 for example, would have worn a gown of silk from India, underclothing made of linen from Holland, and shoes made in England which had gone through complex trades and a lengthy voyage across the ocean on a ship propelled by wind. A slave whose freedom depended on trade and commerce too would be wearing clothing made from inexpensive textiles imported just for his use such as a shirt of linen woven in northern Europe, woolen stockings from Scotland, or a knitted cap from Monmouth, England. Clothing and goods worn at the time came from all over the world, although most of the fashion ideas came from France.

1770’s Laundry woman with skirts & sleeves hiked up: (left) Mrs. Grovesnor for the Queen, (right) for the British army

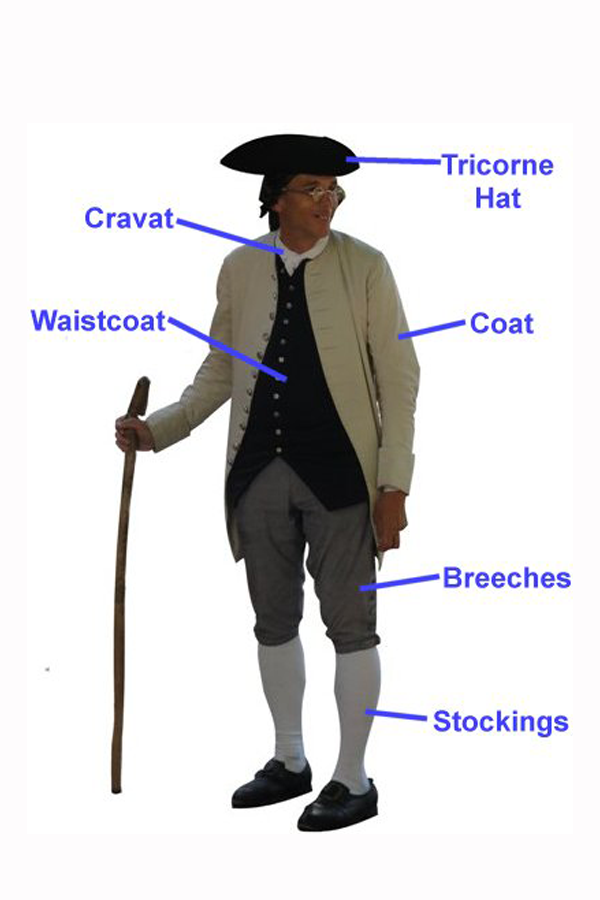

As with today’s people, men, women, and children of the Colonial fashion era valued comfort, warmth, and modesty. They also needed to meet the fashion “rules” of their society. If a woman did not wear the proper undergarments, or if a man did not have on a waistcoat in public, they were considered not dressed, so wearing the right thing was very important to both and women to fit into their communities.

Like people today, Colonists would give up comfort and modesty just to be fashionable; for example, through the 1700’s, women’s fashion said a woman should wear long sleeves and long skirts. Even though it would be easier to wear short sleeves and short skirts while doing something like laundry in a tub, the women wore the long ones anyway and just pushed their sleeves up or hike their skirts up.

Northern women (left) wore warm layers & heavy fabrics while southerners (right) wore cool silks and linens. What women of every shape & age wore had the most to do with where they lived and what they did for a living

Climate was the only thing that had a direct impact on whether people would give up wearing the latest fashion. In places like Virginia where it got very hot, all classes chose washable linen or cotton clothing instead of the many layers and fancy fabrics of northerners. In places like Richmond in the summer, men wore unlined coats and thin waistcoats that were more loosely fit than was fashionable at the time.

Women with money of the south preferred gowns made of “lustring”, a crisp light silk similar to silk taffeta, and some women even went without their stays (underwear) when at home when it got really hot out, but they would always put them on if they left the house.

Peddlers & storekeepers found a profitable market by going west to the frontiers to provide readymade goods to settlers that lived far away from towns & cities

Some upper class men ordered suits custom made to their measurements in lovely fabrics from London. Women could order fancy things like lace, shoes, stockings, cloaks, and even stays (the basic corset-like undergarment) ready-made through shipping trade.

Their gowns were usually made locally though by seamstresses or mantua-makers. Some women from the eastern Colonies made their own undergarments, but only in the frontier areas west was most clothing homemade entirely. On the frontier they even trapped furs, tanned hides, and made their own fabrics by weaving or knitting. Not long into American history did they need to do it all themselves, for traders and storekeepers early in Colonial history made it to the backcountry to make imported and readymade goods available to settlers and pioneers.

The Mantua-maker (seamstress) had to always dress in the latest “high fashion” even if it meant wearing thing beyond her means & impractical for what she was doing

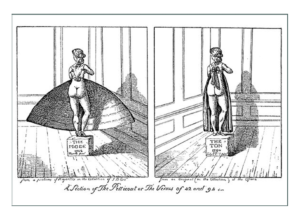

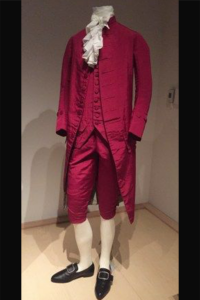

One of the biggest questions that remains today about what people of the Colonies wore is how big people were, because looking at museum examples it seems both men and women were very small compared to those you see today on American streets.

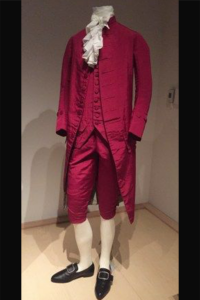

Historic garments indicate women’s waists were between 21 1/2 to 34″ wearing stays (the basic undergarment around the torso which made them a bit larger than natural), with the average about 25″(compared to 30-36″ today), and bust lines averaged about 34″ (compared to 36-42″ today). Men were about 5′ 7 1/2″ tall on the average. Today scientists estimate the average man in America is 5’9″ tall.

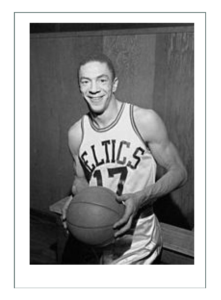

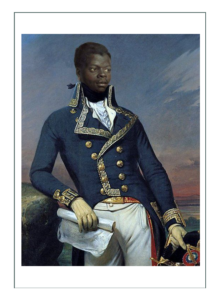

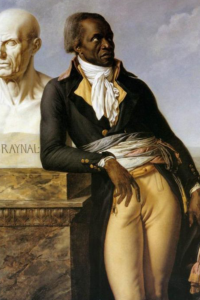

Toussant L’Overture in the 1770’s (right) & Don Barksdale in the 1940’s (left) were both considered tall for their times

CLOTHING WAS VALUABLE

18th Century American Colonies Specifics

Historical interpreters portray Camp Followers in the Revolutionary War, a favor depiction for women

Historical interpreters portray Camp Followers in the Revolutionary War, a favor depiction for women

Interesting facts:

- Hair worn by Royalty at this time rose up to 36″, the highest ever and since in history

- To get the “poufs” in Court dress, women stuffed paper under their skirts, making the era notable for “rustling noises”

- 6 times hand me downs were common

- The insides of clothing were sewn very messy as they were worked over so many times and all the time sewing was done by hands

- Only men were tailors at the time because the stays required strong hands and the men wouldn’t let women into their Guilds

- Every girl was taught to sew, but she did more remaking clothing than creating it

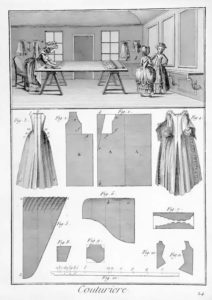

Dressmakers usually went to people’s houses, but sometimes they rented a building and lived over their shop. This shows how the basic “sacque” (dress) was constructed by a Mantua-maker, much the same as today

Everything was sewn by hand. While women did sew and repair their own clothing and that of their families, it was more typical they would buy either used clothing from a peddler or a traveling tailor would come and stay at their house if they were wealthy. Tailors and dressmakers would alter, repair, or remake clothing more often than they created it. Tailors were the ones who made stays, bonnets, and most undergarments and they were always men because they needed strong hands.

For working and rural folks, tailors or mantua-makers would rent a shop in town for a few weeks and sew for everyone in the area, and then move on to a different place. They often came with the seasons so they could change and adjust clothing to suit the weather. The customer would go into town to take measurements or try things on, but would have the final package picked up by a neighbor since they didn’t go to town often when they lived in the country.

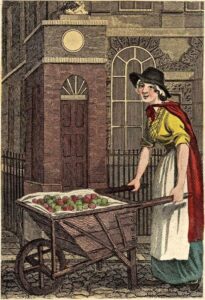

Selling used clothing was very good business, and peddlers went town to town. In big cities, there were special market streets outside set up just for the selling of used clothing

It was very typical for an employer to give an employee hand me down clothes as a job benefit, and the used clothing business was very profitable because clothing was difficult to get and expensive. A man’s suit at the time cost the same as a sofa in the 1770’s.

We have excellent examples in museums of all types of clothing from working women to fancy royal Court dress because people took very good care of their clothes. Many say there are not good examples of poor or working class garments in museums, but the museums have a little secret. Because visitors are more interested in seeing the fancy clothes of queens and kings, the museums store the not fancy and not exciting to look at clothing in closets. They bring them out for special events and programs.

DESIGNS FOR WOMEN & GIRLS

If you were a Patriot Spy in the Revolution, you were still fashionable, but in a different way so you could carry your firearms in your gown

Colonial women paid attention to French and English design ideas and then bought or had the closest they could make out of what they could afford, and what they could get. Depending on where she lived and what she did, a woman would change the fashionable idea just a bit to make it work for her needs. That meant Colonial fashion was usually more functional than high fashion of the day.

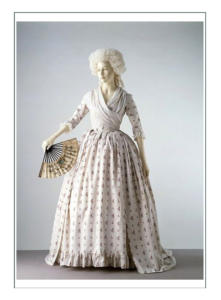

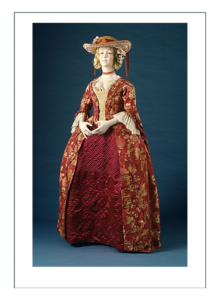

The basic “sacque” was worn by young & old women alike of all social classes. It was the difference in decoration, fabric, & fit that distinguished one from the other (1742 sacques)

All women and girls at the time wore about the same thing, although it was changed a bit for function. Everything was based on the same loose dress called a “sacque” or “mantua” as it had been for half of the century before. A dress at the time was called a “robe”. Through the years the “robe” design changed as it was tucked or pleated and sewn in different ways to make it hang or wrap differently, or to raise or lower the neckline or hem, but it was still basically the same thing until 1800.

The “sacque” was still the same thing even made out of poor fabrics & worn to “nubs”

Girls wore the same as their mothers. Everybody wore the same thing, actually, as employees wore the hand-me-downs of their employers. Class status was very important at the time, and the design and quality of clothing was a way women showed whether they were a working girl or the wife of the Governor. While the shape and styling was the same for everyone, the quality of the materials and construction and the amount of wear on the clothes indicated class status.

A girl living in the woods with her mother might wear a robe made of linen dyed tan with walnut shells, while a fine English lady might dine in Boston wearing silk floral taffeta and silk ribbons from India. Sometimes a short skirt would indicate high status, and sometimes a long one. A farmer’s wife would wear one petticoat, and a fine lady three.

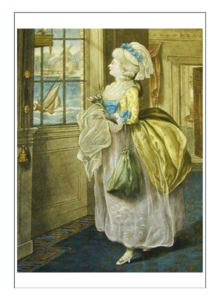

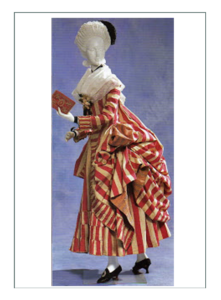

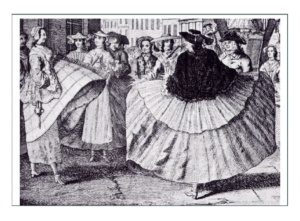

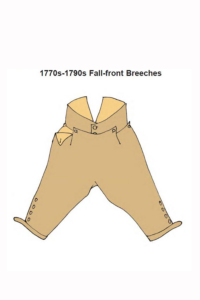

The 1775 high fashion French based fashion silhouette had a big head, VERY wide hips, & an upside down cone shaped upper body/torso with a BIG bust

All the women would, however, be wearing the same design to create a certain “silhouette”. A “silhouette” is the recognizable shape of fashion as it changes, and the Late Colonial/Georgian silhouette was one of a big head, wide hips, upside down cone shaped upper body, and big bust.

The little red cloak served the very poor to the very rich for men, women, & children for almost 200 years

One of the notable fashions of the era for every girl and woman of every class was the red cloak. The “Little Red Riding Hood” worn by girls to birthday parties on the lawn to serving girls.

The Dress

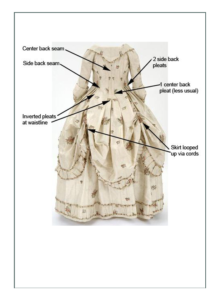

The Basic Sacque

The main garment that started the era was called a “Sacque” or “Mantua”, and it was limp. As the 18th century moved into the 1770’s, the mantua was stiffened and decorated. The way it was put together changed a bit depending on the geographical region, but the overall look was the same.

Robe a l’anglaise

In America there were two main versions before 1770: the “robe a la francaise” which was a gown fitted in front that had straight pleats down the back, and the “robe a l’anglaise” which had a fitted waist all around. The terminology is French, because France was starting the fashion trends at the time.

(Left) “Robe a la Polonnaise”; (center left) authentic Marie Antionette’s “Robe a l’francaise”; (center right) “Robe a l’anglaise”; (right) “a l’anglaise” worn by lower classes too

In 1770 the “robe a la polonnaise” was introduced. It had a fitted waist, but there was a front opening. This would have the skirts of an “open robe a l’anglaise” pulled up like drapery into big poufs at the side or back and was known as a “shepherdess look”. Women wore this look with live sheep in the parks in Paris!

Robe a l’anglaise as the every day woman wore it

1776 Specific

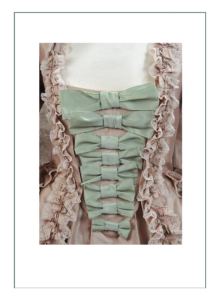

The year 1776 featured a somewhat square bodice with fancy stomacher and lacy sleeves

In 1776 women and girls’ necklines were wide and low and for mid to upper classes usually trimmed with fine lace or at least ruffles. There was a piece in the front of the bodice called a “stomacher” which had been used for the previous century as part of the undergarments. In 1776 it become sewn into an as part of the top of the dress and was often very decorated. As 1780 approached, many women added frills and pleats and fancy work on the bodice, sleeves, and along the front of the “robe” (skirt).

Rich or poor, fitted or loose, it was still the same design

Among others, the “open robe” gained popularity. This was a dress constructed like the “a l’anglaise”, the “polonnaise”, or “la francaise” which had an opening in the front of the skirt. This allowed an underskirt called an “outer petticoat” to show through, opening many design ideas for embellishment of the skirt opening and the underskirt that ranged from quilting to elaborate embroidery, to fancy scallops and ruffles.

Women and designers played with matching colors and contrasting colors so there was a huge variety of design possibility. The amount of frill and the type of fabric made the difference between Court and working woman’s fashion. The “open robe” of the poor had the same construction and overall appearance, but was of coarser fabrics, more natural colors, and of a looser and more comfortable fit than high fashion of the day.

Prints & Colors

Floral prints were very popular, as were tiny prints as seen in these real “open robes a l’anglaise” of the mid 1770’s. The short version was either a “Short Gown” or a “Caracao” depending on the construction details

Most outfits were either plain in color or had tiny prints or delicate flowers. Stripes were very wide in the 1770’s, and often had flowers in between the stripes. New trade with India brought in beautifully dyed prints and stiff silks, so someone with money could wear beautiful fabrics, while those who made their own fabrics or could not afford anything imported wore linen, wool, or flax.

Light colors were for dress up, like First Lady Martha Washington’s robe (right) that she wore to the French Court

Light colors were common for dress up, and darker colors for working. Generally as the 1700’s progressed, the overall look went from the older, darker fabrics, to brighter and lighter ones. Petticoats (“skirts”) were often of colors that contrasted with the main robe (“dress”); e.g. blue with gold or green with yellow. Petticoat and robe were sometimes of the same color, but one would be darker or lighter than the other like light green with dark green in the same hue.

Queen Charlotte of England in Court clothing with her children show the light colors preferred for formal wear in the 1770’s

Interesting Facts about Colonial Women’s Clothing

- Hair worn by Royalty at this time rose up to 36″, the highest ever and since in history

- To get the “poufs” in Court dress, women stuffed paper under their skirts, making the era notable for “rustling noises”

- 6 times hand me downs were common

- The insides of clothing were sewn very messy as they were worked over so many times and all the time sewing was done by hands

- Only men were tailors at the time because the stays required strong hands and the men wouldn’t let women into their Guilds

- Every girl was taught to sew, but she did more remaking clothing than creating it

Women & girl historic interpreters in authentically reproduced costume ensembles (above)

Common Factors Scotland and the Colonies

The Underwear Basics – Summary

Undergarments

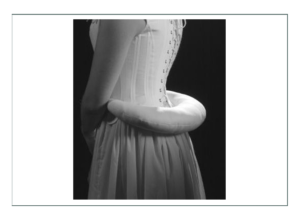

Under any 1770’s ensemble, regardless of fancy or plain, were the basic undergarments stays, stockings, and at least 1 inner petticoat. Difference was quality of fit, fabric, materials, & construction

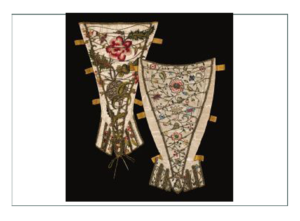

Pockets

Pockets were worn on the inside and only seen by the woman herself

Women did not carry anything in their hands. Most needed their hands for the many jobs they did during the day. Pockets as we know them today, had also not been invented yet.

Because the petticoat (skirt and underskirt) was split between front and back and tied on, it left a gap at each side where a woman could stick her hands in. It was on the inside, tied around the waist of the stays, that a big bag called a “pocket” was hung.

Many women enjoyed making these elaborate and had extensive embroidery and crewel work. Some were made from fine fabrics, but most were of plain sturdy linen that could hold all the things they needed to carry.

Since the fashion was to have huge hips and rear end, it was easy to store all sorts of things under the petticoat which acted like a kind of “curtain” hung on a rump or paniers.

Paniers

Paniers

As the 1770’s went on, the skirt went very wide and was supported by metal and cloth structures underneath called “paniers”. The underskirt was quilted or embroidered and became quite fancy.

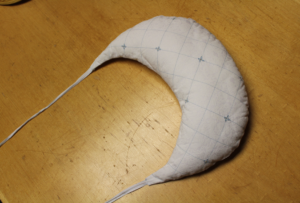

False Rumps, Bum Rolls

“False Rumps”

The “Panier” was mostly worn for very fancy occasions like going to court, so regular women and especially those in America abandoned them before the end of the War and wore “bum rolls” or “false rumps” instead. These were sausage like tubes that were mostly in the back over the rear end and were used to lift up the skirts in back.

Shift (Later called “chemise”)

Shift

The most basic undergarment was worn neck at the skin from top to bottom. It was called a shift for those speaking English and a chemise for the French. Later everyone called it a chemise and it was worn in various forms until about 1910.

The earlier shift was typically of linen, narrower through the body, with a finished neckline that was fit to the woman but not adjustable. Sleeves were past the elbows and intentionally poked out of the bodice sleeves. Gores were more angular than the later styles, so that the upper part was a bit more fitted. Some of these had ruffles at the neck and/or sleeve that would show as part of the finished look of the bodice.

White parts showing were the shift

In 1770 the shift was almost always of the finest linen available in a bleached white for most, and unbleached or even brown or the fabric’s natural colors for others. The design was to accommodate how low the neckline was so it would or would not show depending on fashion of the day.

From 1740-1780 the shift had sleeves almost to or past the elbows and they often would show outside the sleeve of the robe (gown/dress). The neckline of the shift/chemise was somewhat fitted and often had a string to adjust how it lay around the neck. Some had tiny ruffles or lace put on the sleeve and neck edges so they would peek out of the dress.

The later shift was called a “chemise”, and it had short sleeves with a slight gather on top, a wider body, full length gores, and a drawstring. This accommodated the low and varying necklines of the later era and was versatile to be worn with Colonial OR the upcoming Regency fashions

By 1792, the waistlines had risen, and necklines dropped drastically. Sleeves were to tight to accommodate the 3/4 sleeve, and the next short sleeved style of 1800 would demand it be cut off. The shift had to change.

After 1780 the shift’s sleeves were made shorter to accommodate the short poufy sleeves of the main robe. Necklines and the overall width were cut bigger and wider then, and could adjust wide or narrow to accommodate changing necklines. Shifts were always hemmed 1-2″ below the knee and had special construction that used every inch of the fabric wisely.

Stays

Click here to see the extensive research on stays before reading on

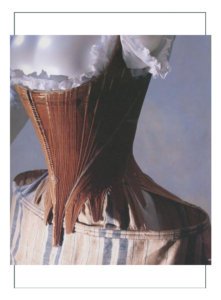

Stays made you have good posture

The main undergarment to make the silhouette of the day was called “stays”, which were the predecessor to the corset. Since there were no bras or panties, they had to have something on! The purpose of stays was to trick the eye into seeing an upside cone. See the following special section on 18th century stays.

Girls wore stays starting at age 6. Some were fancy like real ones (left & right) or modern reproductions (center)

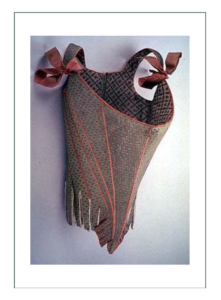

Authentic fully boned stays made in American 1775-76. There were many designs & materials used, but pink was a favorite with brown a close 2nd favorite.

Stays were made of many things, but most were of several layers of linen fabric or silk. They were worn over the entire upper body but under the arms so they made a woman stand up straight and tall.

In the 1770’s some stays did not have straps, and were made very stiff using “bones”. Stays were somewhat tight but comfortable so women could work in them. Because most Colonial women worked outdoors, they had less stiffening than upper class women who stayed inside and didn’t have to bend so much. Whale “baleen”, the cartilege from a whale’s mouth was a favorite stiffener for “boning”. Today’s “stays” use bamboo reeds, metal, or plastic boning.

Outer Petticoat

The petticoat worn under the robe but visible on top was called the “outer petticoat” (above). White was typical as it was easy to clean since it was out in the mud & weather, but other colors including extreme ornament, quilting, and embroidery were typical for upper classes.

Inner Petticoat

The “Inner Petticoat” was special & personal to a woman. It was often beautifully embroidered or quilty to taste. The Inner petticoat keep her warm & prevented people from looking up her skirts

Petticoat was the name of both an under and top garment. It would be called a “skirt” today, and was worn around the waist and hooked onto the bottom of the stays so it wouldn’t droop. The number and type of petticoat(s) indicated a woman’s occupation, status, and class. The more she had, the higher class she was. Red flannel inner petticoats were a status symbol and a favorite of women of all classes.

Mobcaps

Some modern interpreters have taken the BIG mobcap to the extreme!

There were many designs for mobcaps, but the most common was white with a simple ruffle around the face as The Wheatley cap (sketch of Phillis Wheatley rimmed in gold and those that look like it) had trim & is available as a sewing pattern today

Mobcaps were worn by every woman of all ages and classes all the time from the 1760’s to 1800 (except when wearing a wig and ship on the head). Women had fancy caps with lace and complex pleats and ruffles to wear for dress up, and plain small linen ones for every day. The “Phillis Wheatley” mobcap has been made into a commercial pattern available to re-enactors today. It features complex pleats and ribbon decorations and lace that most caps did not have at this time.

Straw Bonnet

The flat crowned straw bonnet was worn flat or bent in a variety of ways both up and down

A very wide brimmed and flat crowned hat, called a “Straw Bonnet” was worn over the mobcap. These were bent and shaped in all directions and either worn plain or decorated with ribbons and flowers or embroidery. Most often the bonnet was worn over the mobcap and tipped precariously forward or backwards. The bonnet was pinned to the mobcap using a small hammered metal straight pin; predecessor to hatpins of the next century.

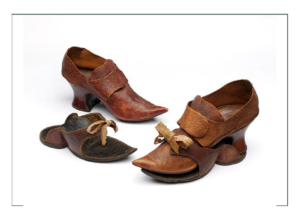

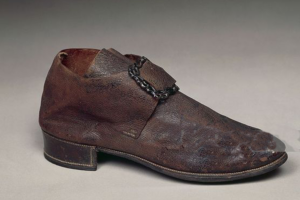

Footwear

While black was the favorite color for daily wear, women dyed their shoes or covered them with fabric to match their petticoats. “Mules” (right) were made by a cobbler who made a doll size pair as a test run of a new design.

Shoes for men and women were very much alike and black leather was the most popular. They either tied or had buckles and straps. For high fashion wome would cover their shoes with the same fabric as their robe, or would wear coordinating silk. Heels varied in height depending on if a woman was working or for dress up. Mules were a shoe without a back with a small heel that were inexpensive and easy to work in.

Modern reproductions feature the tapered heel of the mules or the flat heel. Historically there was no left and no right shoe.

Reproduction shoes are designed to fit the modern foot which is wider and has a left shoe and a right shoe.

Aprons

There were as many individual ways to design and wear an apron as there were women who wore them. This garment was completely individualized, although most typically they were of a plain white or natural colored lightweight linen. Working and lower classes wore some linen subtle stripes or dark solid colors.

Aprons were worn by almost every woman all the time. For those working, they served as protection, tucked up to become carry bags, warmth, modesty, and indicated status. For those of upper or non-working classes, they were decorations and ornament that had some function to protect garments and to achieve the desired fashion effect.

There was a HUGE variety of fabrics, designs, and ways to wear aprons throughout the era. Typically they were a rectangular cloth, most often of linen but also could be of cotton or decorative fabrics like lace. They hung on a simple twill tape tie, or a small waistband with tie.

Fichus/Tuckers

The approximate 30-36″ long triangular “scarf” you see in almost every image and extant garment is called a “fichu”. When the bodice got really low, the fichu saved the day in providing warmth and modesty. A “Tucker” was a smaller piece of fabric laid horizontally and tucked into the bodice at the bottom to hide the bosoms.

There were many, many ways to wear a fichu. Most typically it was folded into a triangle and wrapped around the neck so the points could be crossed in the front. Some fichus, especially the ones worn by working women to protect themselves and their clothes, also had strings tied to the points so they could wrap around and tie in the back of the body. Most just crossed over the front and had the points tucked into the waist of the petticoat, or drawn inside the lacing strings of the front of the stays.

Larger or more decorative fichus were shown off by wrapping outside the bodice and then tucking into a button or special flap designed just for it. There were many with lace, embroidery, and other fancywork, but most were plain white, natural, or ivory sheer or lightweight linen.

How to apply History to Design

We have discussed world fashion at the end of the 17th century into the end of the 18th, and we have introduced the basic concepts of design through 3 French Kings. We then applied those concepts to the lifestyles and adaptations of Colonial women in the “New America” which would become the United States in the middle of the 18th century.

We now, as a predecessor to design decisions, will touch on the specific details of women’s dress at the time that can be used for expressing character, time, and place. We will then summarize Scottish dress. Finally, we will take what we have learned about women in the Colonies and in Scotland from 1745 to 1775, and look specifically at what is common to them all that can be used for this character depiction.

In this section we also will look at the silhouettes of larger women of the day to observe how the fashion of the day was still maintained regardless of body shape or size.

Petticoats (Skirts)

From 1690 until the 1760’s, the “bustle”, a supporting pad or structure placed under the back of the skirt and over the rear end was worn in various forms. In the 1760’s, the bell or domed hoop was reintroduced, taken from French fashion 100 years eariler. The Domed hoop was first worn by the English in 1710 as it was revived from the past, and France followed in 1720 be reintroducing it into Court apparel and High Fashion as (discussed above) the reigns of the King Louis’ crossed over, leading to change in fashion leadership.

The “ellipse”, a phase of the hoop skirt of the 18th century, was made by compressing the hoop front to back and widening it side to side. From 1740 to 1770 these went to extremes as Court apparel in France and England among other countries. In France, the style persisted until 1795. Some paniers were worn even well into the 19th century.

The “Dairy Maid” style, the Polonnaise, was achieved by either pulling and overskirt through the side slits where the petticoat was tied, or by use of draw cords like a curtain. Cords were either buttoned or tied to the waist on the outside of the dress (robe). Starting in the late 1760’s, this style prevailed through the 1770’s until the bustle returned as a “bum pad” in the 1780’s in a softer, more natural look. The “bum roll” became tubular again, like it was in the 1740’s.

Bodices were very much the same shape and form regardless of ornament through most of the 18th century until the very end and the Napoleonic or Regency Era. Most were tightly fitted or tailored with tight, pointed waistlines. Waistlines gradually lost a strict point in favor of softer and rounder looks as they also rose up to and above the natural waistline as the century progressed.

The main difference in bodices through the century were how they closed in front or back. Primary methods were:

- Open, with a stomacher and laced in front

- Fully closed by invisible lacings or hooks

- Pinned down in front with hammered pins somewhat like nails

- Back closings (only mid-century)

-

Decorative stomacher popular 1740’s-70’s with hidden front lacing hooks or loops behind the main fabric. This allowed flexiblity in the fit for “gain a pound; lose a pound” or if the stays worn underneath were laced differently each time

A typical ensemble had one of these:

- An overdress and underdress (robe and petticoat(s))

- Bodice and skirt cut separately and joined at the waist with sometimes waist in the back still attached (“en fourreau”).

- The exception was the Sacque (see Colonial above) which flowed freely in the back AND the front

- Combination of a jacket and skirt, especially for riding horses; e.g. caraco typical of 1770’s

Terms:

Robe a la francaise: The back fullness was formed into box pleats at the neckline, falling freely to the floor

Robe a l’anglaise: When the back of the bodice fits closely to the body either by pleating or seaming

DATE SPECIFIC DETAILS

DATE SPECIFIC DETAILS

There was not a distinct line between 17th and 18th century fashions. As with most of history, things were evolving and crossing over. Women were wearing their favorite old caps into the next century, while others embraced whatever was new.

In the 18th century the basic woman’s ensemble was still a “gown” or “robe” where the bodice and skirt were coordinated. Some were sewn together; some worn apart. Bodices were like fitted jackets, and skirts were worn open or closed. Bustles were in style from the late 1600’s and reemerged in 1710; disappeared in 1775, and came back in the next century. In between were hoops and paniers.

1700-1730

Design Details

In the 1710’s, bodices were always short-sleeved with a low decolletage. The “Open Robe” prevailed. The bodice was most typically joined to the skirt, and in 1710 the back was very long waisted and fitted.

The front edge of the bodice was stitched with revers called “robings” that went around the neck and ended in a V at the waist in front. The front was plain and simple until it got ornate again in 1745.

The front had an underbodice or stomacher and sometimes instead of that the stays showed as the outer garment. There was an underbodice that was sleeveless, worn like a stomacher. Stomachers were padded triangles with straight tops and pointed or scalloped at the bottom Things were pinned to the tabs.

The 1720’s had less robings. Bodices closed with buttons down the front to the waist and had a round neckline. Sleeves ended in cuffs at the elbows and shoulders were pleated.

Influences & Innovations

Mme Maintenon (King Louis XIV’s advisor, supposedly his 2nd wife though it was never announced nor celebrated, she had significant political power) restricted and discouraged innovation in fashion although the King would have liked to have more. She liked green and gold, and had Danish influence which included the shorter jackets that would be popular later. The design was very basic with lovely fabrics.

The Watteau in 1720 with double back pleats was key in this period. The Watteau back is characteristic of the Robe a la Francaise.

The “Sacque” was like a big tent hanging in front and back, especially when worn over a hoop petticoat which hid all the body flaws or a big body. These were favorites to wear around home, while traveling, or for maternity. Most women wore a “Sacque” for daily wear until the 1730’s.

France was considered the source of European and so Colonial fashion throughout the 18th century, but the English contributed the concept of hoops. By 1730 the dome-shaped hoop under the inspiration of Mlle Carmargo, a beloved ballerina, was worn short and wide like a ballet costume. It had domed skirts, narrow stomacher in front, and a gauzy neckerchief.

Sleeves got smaller and smaller from 1710 to 1730. All women wore “Lappet Caps” with folding fans and gloves. Footwear had blocky heels and VERY pointed toes. They wore “clogs” which were wooden platforms hooked to the shoes to lift out of the mud. Shoes were often covered in cloth to match the dress.

1730-1750

Design Details

Skirts increased volume and were worn over further enlarged hoops. Necklines widened with new emphasis on horizontal lines. Engageante sleeves were added to put “froth” at the elbows.

Bodices were long, smooth, and still SHARPLY pointed. The stays underneath were important to keeping the flat and smooth front. Stays were the same shape as the bodice.

Influences & Innovations

In the 1730’s and ’40’s necklines were more open; broad, low, and curved like Queen Marie Leczinska (sister of Louis XV) modeled. This neckline prevailed all over the world, and into Marie Antoinette’s reign.

Closings were center back typically, so the front could be decorated with jewels, flowers, ribbon, etc.

The ’30’s and ’40s saw revival of the mid 17th century neckline and sleeves also, which had a tiny sleeve cap with huge poufs. There were other types of sleeves especially of jackets that were looser all the way to the elbow and then ended in lace.

In 1730 the “en fourreau” back was invented. It was the back of the bodice that was pleated and had a single seam from neck to hem in the center back.

Petticoats were different color than the robe most typically and were elaborate.

The “Open Robe” of “Robe a l’anglaise” construction was a favorite until the 1780’s. It had an “en fourreau” back, and could have robings or a fill in (showing in front) stomacher – or not.

A “Zone” was a type of “Open Robe” which closed with a false waistcoat called a “zone” and had a “falling collar”

A “Closed Robe” was popular from 1700 to the 1760’s. It was also called a “Wrapping Gown”. The bodice was always close fitting, had a low round neckline, never any robings, and women wore a tucker scarf because the bodice was so very low. The fronts often crossed like a wrap and were closed by a brooch or pins. Sleeves were smaller than the “Open Robe”, and styles varied quite a bit. They were generally less ornamented but did have ruffles. These were worn over hoops of all types and sizes.

Closures in this era:

- most often cut to meet at center, or had an extension on a slanted line shoulder to waist which was then fastened or hooked

Robe a l’anglaise with center front pinned closure - Overlapping center front which was filled with the fichu or tucker to hide closure like example above

- Zone Gown cross closure using buttons or inside (hidden) hooks and eyes

-

Modern reproduction of Zone Redingote with crossover and button closure - Sometimes the stays showed instead of a stomacher, with damask or embroidered silk

- Ribbons and lacing of the front opening through eyelets attached to the lining behind; late in the era

- Graduated bows of ribbon “eschelle” (Mdme Pompadours favorite!)

The bodice was connected to the skirt as an “Open Robe”. This meant the petticoat showed. The petticoat might match or it might contrast.

In the 1740’s there were new hoop shapes. They spread wider side to side. Cloaks were the outer garment, and capes were very popular – some full length. Capes and cloaks buttons in front and had slits for the arms to stick through.

1740’s sleeve cuffs were larger than in the 1720’s or ’30’s, and were fuller and shaped like a bell. They were stiffened to stand away from the arms.

Hair softened in the ’30’s and ’40’s. Loose curls were worn in back and held under the tiny lingerie type cap. Some were very fancy with lace or made entirely from lace. Long curls falling over bared shoulders were popular, but they still wore a cap. These caps were a bit larger with ruffles that came to a peak at the forehead.

Added on top of the cap was a low-crowned and wide-brimmed hat. Sometimes they had ribbon ties that pulled the sides down over the ears.

Heels on shoes were more slender and higher than the decade before, and the points got even pointier. Aprons were worn for everything – even dress up. They varied from a plain and simple solid colored or white linen with a bib to an entire lace confection. There were many of embroidered silk taffeta.

Jewelry was rarely worn except diamonds. Mostly pearl necklaces, earrings, rings, and a pearl

chatelaine (worn center front under the bodice and over the apron a jeweled flat strap to hold tools).

Flowers were worn very much, so much so that vials of water were stored in pockets attached to the shoulders and waist, or tied to ribbons at the throat.

1750’s-1760’s

Corsetry (Stays) became an art form in these decades. The included stays specially designed for riding, breast feeding, maternity, and other purposes by 1769. Young boys and girls wore stays – both exactly the same regardless of gender.

The goal of the stays was to create a smooth and flat surface that didn’t show. The bodice would lay over the smooth curve of the stays. Key features of stays of this time included:

- Broad, low, curving neckline

- Brocade, metal lace, quilting (to protect bones)

- Front could be displayed as an outer garment, but they were undergarments at this time

- Hip pads were tied to the bottom tabs for hoops to attach to through eyelets

- The outward thrust of the stays at the top was the key to note this specific time

- Sometimes women wore these without an outer garment around home

- Busks, a wooden stick like a paint stick placed center front vertically, started to be used to reinforce strength, but mostly to keep the rigid verticality demanded.

- The era was directed by Mme Pompadour, her name meaning either a hair paid or a type of taffeta silk (she was 34 years old in 1755 when she was advisor to the King)

Skirts were not as extreme as before. It was a time of femininity as ruffles, ruching, lace, robings, and flowers were abundant. It was an interpretation of “Roccoco” which meant a light and airy feeling with subtle colors, continuing curving lines, and intricate details, following Mme Pompadour for whom anything she did made the world news.

The wide but square neckline was new and outer flutings along every edge replaced robings of the previous times. Stomachers had echelles, and the inner and outer petticoats were both more elaborate and trimmed.

Sleeves were yet closer fitted, with BIG engageantes and graduated ruffles; usually 2 instead of the winged cuff. Sleeves were higher and had ruffles and lace. There were bows at elbows and more elaborate neck frills. Pearls were still popular at neck, ears, and wrist.

Hair was worn back from the forehead but close and soft. It would evolve into the “conehead” in the next decade. A damask coat was designed to fit over wide hoops, and women also wore wraps and capelets over just the shoulders. Shoues were more rounded at the toe and had a shorter heel with buckles.

Paniers of the day were on hinges so they could collapse to sit or get through a door.

1750-60’s Something Entirely Different

It should be noted here that we have been talking about High Fashion and Court styles. Fashion was very much dictated by class and social structure; by the occupation and financial status of a woman. All the fashion ideals of each era were consistent all the way down through the classes, but it was the quality of fabric, dye, fit, and technique that varied greatly.

One thing of particular note as the 1770’s approached was that Trade exploded with India, Persia, China. Cotton became the BIG thing and was expensive and rare. Women loved cotton and especially the prints that came out of the Asias and India.

By the time Marie Antionette took the fashion reins out of the hands of Mme Pompadour, orientalism was very much a part of her education and that of many nobles and royals of Europe. The “chinoiserie” style of fashion design started with Pompadour, but exploded with Marie.

The Chinese imagery in particular with pagodas, and motifs and patterns was very very popular. The rich colors of Peruvian fabric initiated the striped florals notable of the 1760’s into the 1770’s. India cotton prints were well documented in texts and trade and import records, although for some reason rarely did a woman have her portrait made wear printed cotton. Only extant garments really show what women loved for daily wear.

One fabric in particular, Indian muslin, took the world by storm because it would make clothing easy to clean, comfortable to wear, and would lead the 18th century into the next Regency era of the “Little White Dress”.

There was a growing “Black Market” around the world in the trade of these imported goods, and a whole romance around piracy and intrigue in their places of origin.

1770’s

It was a time of extremes. Louis XVI was on the throne with Marie Antoinette joining him by 1774. Marie liked dance, theater, and masked balls, so developed with French designers, interesting costumes of wild imagination and for theatrical purpose.

At her Petit Hamil (Swiss Village like little farm) she wore shorter skirts with an emphasis on the polonnaise. She tucked them up into the waistband, like the farmers did. Every women followed her example because it made sense, but nobles took the “milkmaid” style to extreme and took live sheep into parks and pretended to be shepherdesses.

Records are conflicting in saying that Marie hated Court fashion and preferred her simple styles that would evolve into something entirely different by the 1790’s when she was beheaded. When she wore her simple styles, she was accused of not being “Royal Enough”, yet when she wore Court Forma Wear, she was accused of being “Excessive and Wasteful”. No one knows the truth.

We do know she wore the extremes, regardless of whether she like to or not. She had HUGE paniers, high hair, garlands, fabrics, fur, and fringe. To us today it looks like “fairytale fashion”.

Necklines went scandously low, and were softened and made wearable by adding a lace or fluting around the edge. Sometimes she wore the stiff ruff collar of the century before.

“Pannier” means “basket”. Those worn for daily wear were narrower and closer to the body. Marie wore them with her peasant look, and so did the real peasants of France. The huge paniers supported the polonnaise with the heavy “poufs”.

This was accomplished by cutting the over petticoat on the grain which allowed it to be very full yet to have an even length parallel to the ground even with the hoops underneath.

The waist was a very dep V again; long and sharp. The bodice had a sleep look, and while the prior types of closure were still used, there was an additional method of tieing attached strips through eyelets.

From the 1770’s forward, bodices closed in front edge to edge while the back flowed or laced and was tightly fitted.

“Plastics”, a sausage like trimming stuffed like a sausage, replaced the ruchings and kiltings and stood out with even more dimension.

The Caraco Jacket (see jacket examples in separate section) was an invention of the 1770’s. It was essentially the robe a la polonnaise cut off at the bottom. The first ones were finished with a double ruffle. These stayed a favorite in fashion until the late 1790’s and Regency era.

Hair kept rising through the ’70’s. Queen Charlotte of England led the style for that along with Marie Antionette. Due to having a leisure class in both countries, and a low standard of hygiene, both natural hair was worn high, as well as wigs.

Wigs, worn more by men and rarely by women, were actually more sanitary because they were removed and cleaned. Women would go to a hairdresser only 3-4 weeks at a time. Their own hair would be padded and stuffed and stiffened with flour until it became like paper mache. They would add figures and statues and birds and ships and carriages.

They had to sleep on the hair, and vermin would get in. They would have to slit it open and go on “hunts”. Women were obsessed with their hair, and even low class women attempted to get the look.

A “Therese” was a gigantic head covering to protect the 12-36″ high hairdos. They worked primarily as a windbreak. A “Calash” was like a hinged tent put on top the head. It worked like the top of a carriage.

Women wore “wraps” and a coat called a “pelisse”. It was a hooded cape with armhole slits. They liked to war lots of fur.

In addition to the tucker and neckerchief were “ruffs”. They were small at first starting in the 1750’s, and were like a wired tucker. By the ’70’s they were stiff and stuck into the bodice like a fan. These stiff ones were called “Standing Frills” .

Pattens and clog over shoes lifted feet off muddy ground.

Caps had a great variety by this time. They were mostly made of white cotton lawn or lace and were worn under hats or over tall hair. A “pinner” was a tiny round flat lace cap with flower bunches.

The Mobcap had a full crown that was puffed up with frills. Some still had lappets (side pieces) and some were tied with ribbon or had ribbon decoration, but plain was most common.

The Round-eared cap was notable of the 1700-1760 period. These were round and curved over the ears. After that they got larger and straighter around the head.

Beauty aids included lead in cosmetics used to hide facial blemishes. There were plumpers to fill out lost teeth.

Perfumes floral and especially lavender for the masses were worn because bathing was rare. Sachets were sewn inside garments and into pockets.

Aprons and detachable sleeves were worn for information daywear. Reticules hung by the wrist, fans were used more as the century progressed.