Mary Katharine Goddard Online

Mary Katherine Goddard (1738-1816) was appointed Baltimore’s postmaster in 1775, and may have been the first woman postmaster in colonial America. She originally served under the leadership of Postmaster General Benjamin Franklin, who oversaw the newly independent colonial postal system established by her younger brother, William Goddard. Not only was Goddard in charge of a post office serving a major commercial city, but she was also an accomplished printer and publisher, successfully publishing her brother’s newspaper, The Maryland Journal, from 1774 to 1784. Recognizing the excellence of her paper, Congress granted Goddard the honor of publishing the first copy of the Declaration of Independence with all the signatories listed, in 1777.

Goddard was first exposed to the printing business and postal system through her family. Her father, Giles Goddard, was a prominent figure in the local community, serving as both a physician and postmaster in New London, Connecticut. After his death, Goddard’s mother, Sarah Updike, moved the family to Providence, Rhode Island, where her son William opened his first printing business. Later, William’s mother and sister took over his publications for him when William began to spend his time and finances undertaking other business ventures. As Ward Miner noted in his book on Goddard, “William was the postmaster of Providence, but his mother and sister had done the actual postal work.”1 In the process of overseeing her brother’s publications and printing shops, Mary Katherine Goddard established a reputable name for herself.

As a publisher and postmaster, Goddard believed that she was responsible to her public. During the Revolutionary War, for example, she continued her service, believing in the “American cause” of self-sacrifice for the “commonweal,” or welfare of the public2 Goddard frequently even used her own funds to pay the post-riders to deliver the mail and to cover the costs of printing issues of The Maryland Journal.3 Many of Goddard’s efforts were tied into her role as a businesswoman, ensuring that her subscribers received the paper and that the customers had their mail delivered.

However, Goddard’s contributions to the new nation did not protect her from political manipulation. In 1789, Postmaster General Samuel Osgood ordered Goddard to resign from her post, and replaced her with John White, Osgood’s political ally. Osgood asserted that because Baltimore was to become the new regional headquarters, the postmaster would have to make frequent, long-distance travels — which he stated would be unmanageable for a woman.4 However, it is more likely that Osgood wanted to replace Goddard because the growing port city of Baltimore presented a lucrative source of income and the opportunity to curry political favors.

Refusing to accept her dismissal, Goddard petitioned the highest authorities for reinstatement. She wrote a letter to President George Washington, expressing her loyal service to the state, and claiming that her post office “remained ‘the most punctual & regular of any upon the Continent.’”5 More than 230 Baltimore citizens signed a petition in defense of Goddard’s competence and protest her unfair removal. However, their efforts were not enough, and Washington refused to intervene. Goddard then appealed to the U.S. Senate, but they, too, failed to act.

Unfortunately, even before losing her post in Baltimore, Goddard had been forced to give up leadership of The Journal. Seeing the success of the paper, William, whose relationship with his sister had escalated into a “bitter quarrel,” resumed control of his publication.6 Having lost two sources of income, Goddard financially supported herself for the rest of her years through the management of her bookshop.

Before her death on August 12, 1816, Goddard freed her single slave, a woman named Belinda, bequeathing to her all of Goddard’s possessions and property. While Goddard may have been one of the new Republic’s earliest victims of what would become known in the nineteenth century as the postal service’s patronage system, she would not be the last woman to serve as postmaster.

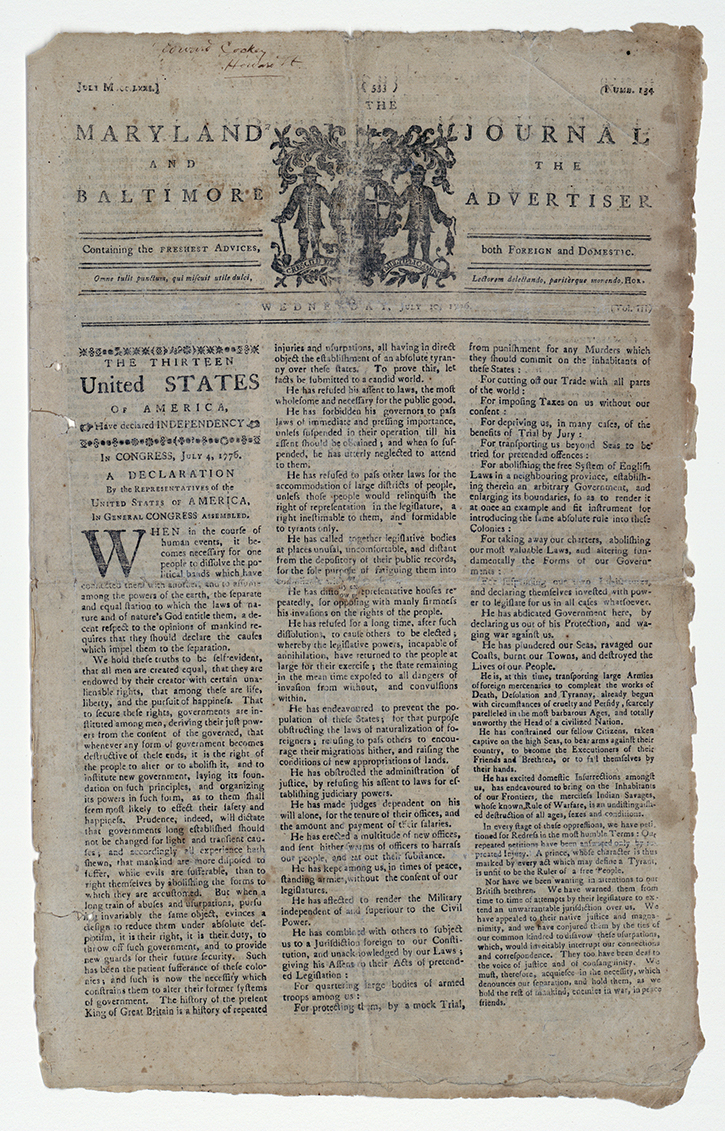

As British forces chased George Washington’s Continental Army out of New Jersey in December 1776, a fearful Continental Congress packed the Declaration of Independence into a wagon and slipped out of Philadelphia to Baltimore. Weeks later, they learned that the Revolution had turned their way: Washington had crossed the Delaware River on Christmas Day and beaten the redcoats at Trenton and Princeton. Emboldened, the members of Congress ordered a second printing of the Declaration – and, for the first time, printed their names on it.

For the job, Congress turned to one of the most important journalists of America’s Revolutionary era. Also Baltimore’s postmaster, she was likely the United States government’s first female employee. At the bottom of the broadside, issued in January 1777, she too signed the Declaration: “Baltimore, in Maryland: Printed by Mary Katharine Goddard.”

For three years after taking over Baltimore’s six-month-old Maryland Journal from her vagabond, indebted brother, Goddard had advocated for the patriot cause. She’d editorialized against British brutality, reprinted Thomas Paine’s Common Sense, and published extra editions about Congress’ call to arms and the Battle of Bunker Hill. In her 23-year publishing career, Goddard earned a place in history as one of the most prominent publishers during the nation’s revolutionary era.

“The ever memorable 19th of April gave a conclusive answer to the questions of American freedom,” Goddard wrote in the Journal after the battles of Lexington and Concord in 1775. “What think ye of Congress now? That day. . . evidenced that Americans would rather die than live slaves!”

Born June 16, 1738, into a Connecticut family of printers and postmasters, Goddard was taught reading and math by her mother, Sarah, a well-tutored daughter of a wealthy landowner. She also studied Latin, French, and science in New London’s public school, where girls could receive hour-long lessons after the boys’ schooling was done for the day.

In 1755, the family’s fortunes changed when Goddard’s father, postmaster Giles Goddard, became too ill to work. Sarah sent Goddard’s younger brother, 15-year-old William, to New Haven to work as a printer’s apprentice. Seven years later, after Giles’s death, the Goddards moved to Providence, and Sarah financed Rhode Island’s first newspaper, the Providence Gazette. William, then 21, was listed as publisher. “[It] carried his imprint,” wrote Sharon M. Murphy in the 1983 book Great Women of the Press, “but displayed from the start his mother’s business sense and his sister’s steadiness.”

Over the next 15 years, William, a restless and impulsive young entrepreneur, moved from Providence to Philadelphia to Baltimore to start newspapers, always putting his mother or sister in charge of his previous businesses as he went. In 1768, William sold the Providence paper and convinced Sarah and Mary Katharine to move to Philadelphia to help run his Pennsylvania Chronicle. In 1770, Sarah died, and William, who was feuding with his financial partners, left the Chronicle in his sister’s hands.

“She was dependable and he brilliantly erratic,” Ward L. Miner wrote in his 1962 biography, William Goddard, Newspaperman. Mary Katharine kept her brother’s businesses running while he did time in debtor’s prison in 1771 and 1775. In February 1774, William handed control of his fledgling Maryland Journal over to her. That allowed him to concentrate on building his most enduring business: a private postal service, free of British control, which later became the U.S. Post Office.

Mary Katharine Goddard took over the Maryland Journal just as the colonists’ anger at British rule surged toward revolution. By June 1774, she was publishing reports on Britain’s blockade of Boston Harbor. In early April 1775, she endorsed the women-led homespun movement against British textiles, encouraging women to raise flax and wool and embrace frugality. She published Common Sense in two installments in the paper, and covered the Revolution’s first battles with fervor. “The British behaved with savage barbarity,” she wrote in her edition of June 7, 1775.

That July, the Continental Congress adopted William Goddard’s postal system, then promptly appointed the more reliable Benjamin Franklin as postmaster general. Mary Katharine was named Baltimore’s postmaster that October, which likely made her the United States’ only female employee when the nation was born in July 1776. When Congress turned to her to print copies of the Declaration the following year, she recognized her role in a historical moment. Though she usually signed her newspaper “M.K. Goddard,” she printed her full name on the document.

The war years were tough on Goddard’s businesses. Because of its meager treasury, Congress often failed to pay her, so she paid post riders herself. She published the Maryland Journal irregularly in 1776, probably because of paper shortages. In 1778, she announced her willingness to barter with subscribers, accepting payment in beeswax, flour, lard, butter, beef or pork. Yet she was able to boast, in a November 1779 issue, that the Journal had as extensive a circulation as any newspaper in the United States.

Goddard “supported her Business with Spirit and Address, amidst a Complication of Difficulties,” wrote her brother and his new partner, Eleazer Oswald, in a 1779 advertisement. In the same broadsheet, they declared that their new paper mill would not interfere “in the smallest Degree” with Goddard’s business.

But in January 1784, William Goddard apparently forced his sister out of the business and took her position as publisher of the Maryland Journal for himself. Later that year, the siblings published competing almanacs. William included a screed that attacked his sister as “a hypocritical character” and insulted her “double-faced Almanack,” “containing a mean, vulgar and common-place Selection of Articles.”

There’s no evidence that Goddard and her brother ever spoke again. When William got married in Rhode Island in 1786, Mary Katharine did not attend. A mutual friend, John Carter, wrote her a letter describing the wedding and suggesting, probably in vain, that the siblings reconcile. “Dear Miss Katy,” begins the letter — a rare window into her personal relationships.

In October 1789, she lost her job as postmaster of Baltimore. The newly appointed postmaster general, Samuel Osgood, replaced her with John White of Annapolis. John Burrell, Osgood’s assistant, justified the move on sexist grounds. Since supervision of nearby post offices was being added to the job description, Burrell said, “more travelling might be necessary than a woman could undertake.”

Two hundred prominent Baltimore residents signed a letter demanding Goddard’s reinstatement. Goddard herself appealed to President George Washington and the U.S. Senate for her job back. Her petition echoes the disappointment she must’ve also felt when her brother pushed her out of the Journal.

“She hath been discharged without the smallest imputation of any Fault,” Goddard wrote, in the third person, to the Senate in January 1790, when she was 51. “These are but poor rewards indeed for fourteen Years faithful Service, performed in the worst of times,” she argued. Her “little Office,” Goddard added, was “established by her own Industry in the best years of her life, & whereon depended all her future Prospects of subsistence.”

Washington refused to intervene, and the Senate never answered Goddard’s letter. She spent the next 20 years running a bookstore in Baltimore and selling dry goods. Never married, she died in Baltimore on August 12, 1816, at age 78, leaving her property to her servant, Belinda Starling, “to recompense the faithful performance of duties to me.”

Goddard, as a contemporary of hers declared, was “a woman of extraordinary judgment, energy, nerve, and strong good sense.” Though sex discrimination and her ne’er-do-well brother ended her career too soon, Goddard left a mark as one of the Revolutionary era’s most accomplished publishers and a female pioneer in the U.S. government. None of Goddard’s letters survive, and she revealed little about herself in her journalism. Instead, our best evidence of her personality is her work, steady yet animated by a passion for American liberty.

At the Smithsonian’s National Postal Museum in Washington, D.C., the story of postmaster Mary Katherine Goddard’s is featured in the permanent exhibition “Binding the Nation.”

Mary Katherine Goddard – Colonial Postmaster and Printer

Two years earlier, she had become Baltimore’s postmaster, a position she held successfully for fourteen years. In 1789, Postmaster General Samuel Osgood removed her from the position.

Osgood wanted Goddard gone so he could appoint a political ally, John White, to the post. White was inexperienced in postal operations and an obvious patronage choice. So to try and quiet potential outrage about giving White the job, Osgood gave Baltimore’s citizens what was, at that time, a far more acceptable reason for removing Goddard. She was a woman. Yes, when the citizens of Baltimore petitioned for her reinstatement, they were told that the position would require “more traveling . . . than a woman could undertake.” And while the petition did finally make its way to President Washington, he declined to overrule his Postmaster General.

Goddard’s fourteen years of great service to the citizens of Baltimore were at an end. Mary did not fare much better with her brother. He returned to the city having lost a hoped for opportunity to run the national postal system. In need of an occupation, he took over Mary’s printing business.

Mary Goddard turned to selling books, stationery and dry goods. She died in Baltimore on August 12, 1816, still beloved by the community she served so well.

Early Postal Women

Women’s roles in early American mail service are difficult to identify. Official records documenting their involvement are rare. Their participation and experiences were more commonly communicated through oral narratives and observations by higher-level officials. In the monthly publication of The Postal Record, a June 1896 article titled “Postmistress [sic] 200 Years Ago” covered the story of the “first keeper of the mail department of Salem” who was a woman identified as Lydia Hill.1 The story was written to give “encouragement” to women of the 1890s “struggling to obtain their rights” in the postal system. The article emphasized that even in the seventeenth century women exercised very important roles.2 Only a few served as postmasters, however. Women usually performed non-traditional postal work, which was necessary to keep the mail service operating.

Given that post offices in early and colonial America occupied the same space as general stores and printing businesses, the wife or female household members who assisted in the shops very likely performed postal duties as well. On May 7, 1764, Elizabeth Franklin, wife of John Franklin and sister-in-law to Postmaster General Benjamin Franklin, was mentioned in a Boston Papers advertisement, selling goods at the family store, which was also a post office. The advertisement said: “Elizabeth Franklin sells at the Post Office in Boston, Genuine Crown Soap, C-andles [sic], Cheese, & c.”3 Even Benjamin Franklin enlisted the help of his wife at his Philadelphia post office.4 Women were not always directly handling the mail, but they helped keep the system running. When post-riders arrived at checkpoints to change horses and to deliver and pick up mail, women household members likely provided them with refreshments and lodging.5

Other early American women acquired postal positions indirectly. For instance, they might continue their husbands’ postal duties after the spouse had passed away or moved on to other career opportunities. References to early American female postmasters include Elizabeth Timothy who was a distinguished printer and publisher in South Carolina. Timothy “continued in the capacity of postmistress,” a position held by her late husband Lewis.6 Her printing office also served as the headquarters for “distribution of local letters, packages, and papers.”7

Throughout the Revolutionary War, women temporarily replaced war-bound husbands or brothers, managing the printing shops or performing postal work. In addition to the historical references and anecdotes of female postmasters is the tale of Tempe Wick, who reportedly delivered military dispatches from Jockey Hollow to Ford Mansion, New Jersey—the headquarters of General George Washington, in the winter of 1777.8

After the war, a subtle but important change in the perception of a woman’s role in the public was noticeable. Citizens who espoused Republican rhetoric were impressed with the “patriotic women” who “supported the war effort.”9 Printer and publisher Mary Katherine Goddard who may have been the first woman postmaster in colonial America to embody the values of “Republicanism”—“independence and the sacrifice of self-interest for the public good”—admired by the public.10 Not very far from where Goddard served as postmaster in Baltimore, Elizabeth Creswell was appointed postmaster of Charlestown, Maryland in 1786.11 Despite the increasing number of recorded appointments of woman postmasters, Goddard’s dismissal in 1789 by Postmaster General Samuel Osgood confirmed the exclusion of women from prestigious political appointments because of a commonly-held belief that they had no right to participate in politics. Since most of the appointments were distributed among political allies, women could not benefit from the system. Thus, Goddard’s unwarranted removal in 1789 was simply a preview of what would develop into the systematization of political patronage under the Jackson’s administration.12