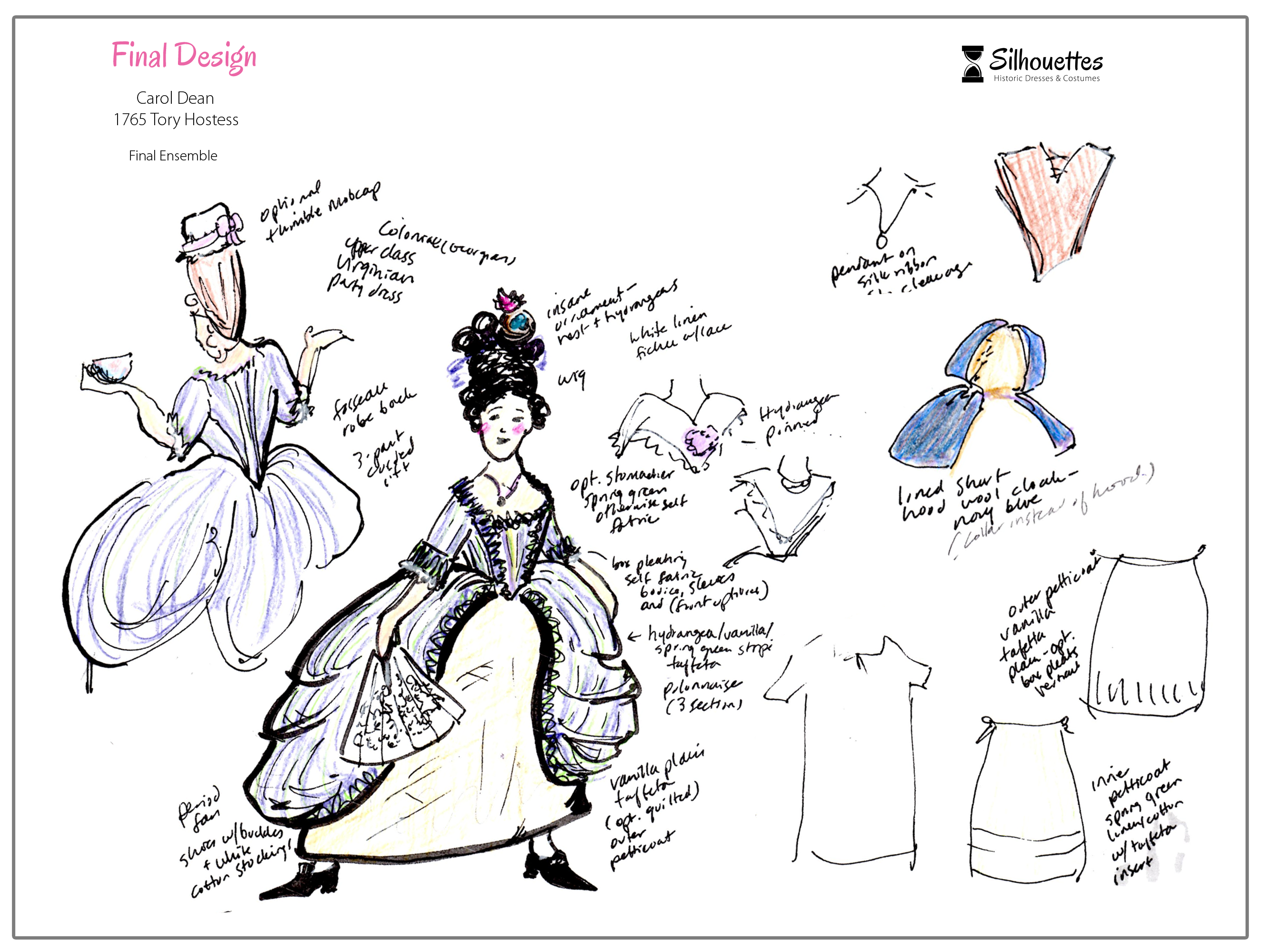

Carol is a member of a major geneological organization which records and documents families who can be traced as direct descendants to America’s Revolutionary War. She will be entering this ensemble into a contest with the organization that will judge her on the basis of her depth of knowledge, research verification, design, & production.

Mary Pegram was a real person. While much of her stories and details have been documented, there are still gaps to interpret. This is the challenge of the project; to fill in the spaces of information to interpret what a real woman in history would have thought, how she would have acted, and what she would have worn.

The bulk of the effort will be on understanding Mary’s personality, preferences, access to goods, and position in the world at a time where her loyalties would have been divided. The rest of the effort will be in maintaining absolute authenticity which means reproduction fabrics, bones, and methods of construction which means each and every stitch must be made by hand.. and preferably by candle or day light.

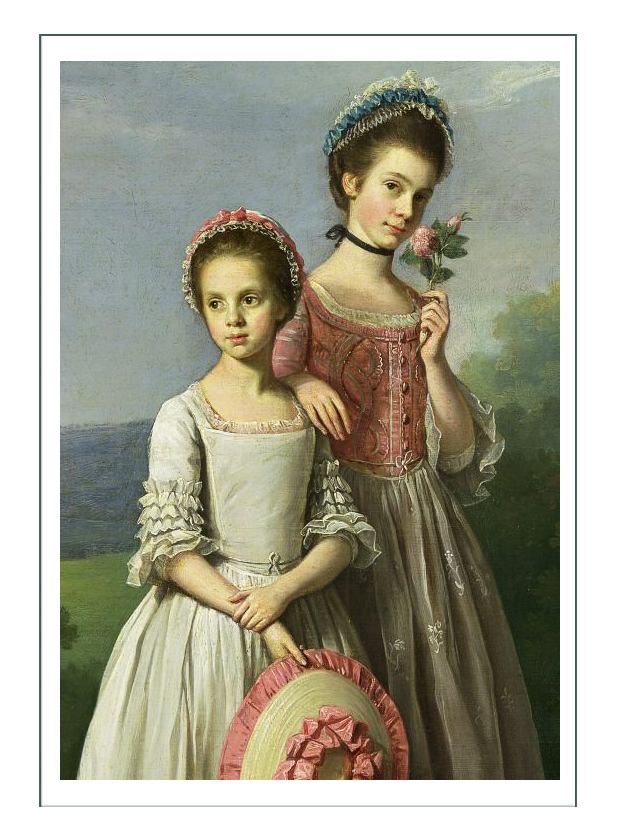

Mary Scott (Baker) Pegram, 1765-1778

This project will be Revolutionary War interpretation at competitions, public “stand up” presentations (“Revolutionary Striptease”), & for in-school educational programs teaching about clothing & culture of the era. The character being depicted was a real person and ancestor of the performer:

b. Nov 12, 1723; d. June 30, 1779 at age 56

MARY’S STORY

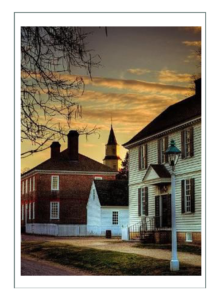

Little is known about Mary or her husband, because records prior to 1791 were destroyed in a fire that burned the Dinwiddie Courthouse in Dinwiddie County, Virginia where her story takes place. Later, Sheridan’s army in the Civil War burned it again, along with all the records of adjacent counties.

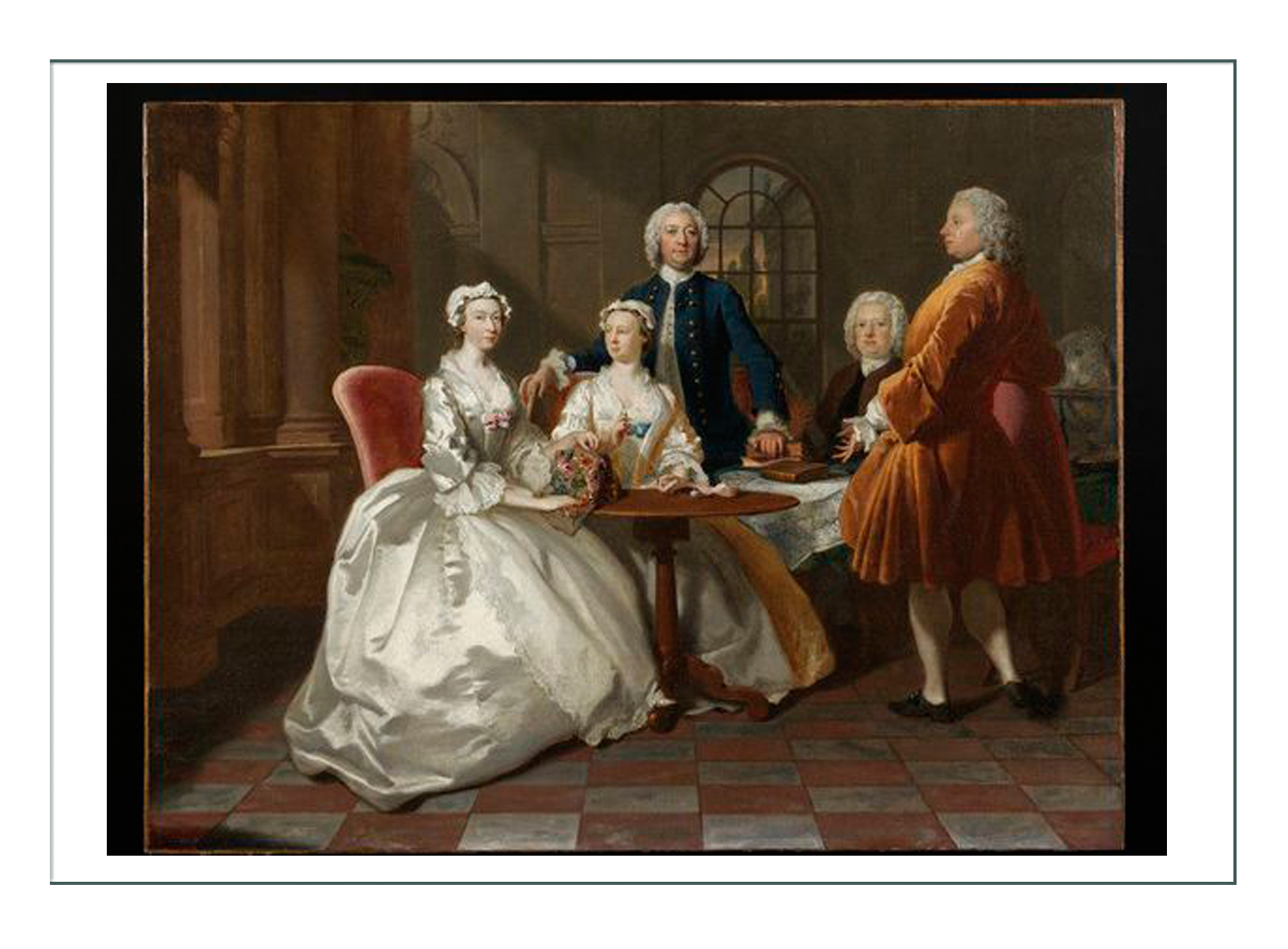

Mary was born in England, of Colonel Daniel Baker and (name unknown) the daughter or Sir Foliad Griffith. Both parents were of English nobility, and you can presume “Colonel” was a purchased rank as was typical of the time.

In about 1740, Colonel Baker was assigned by Prince George (King George would go into exile in 1811 due to “insanity”, this was actually the “Georgian Period” and a crossover between the two Kings) to be on the Governor’s Council of Dinwiddie County in Virginia in the new Colonies. Appointed by The Crown, he came on a ship with his family, and settled in Petersburg, VA. Mary would have been 17 years old.

Edward Pegram was born in 1722 (died in 1816 at age 72) in York County, VA, although oral histories have him arriving alongside the Governor and the Bakers into Williamsburg, VA, having been born in England also. He was a “commoner”, and the record has been corrected.

Edward had just finished an apprenticeship as a brickmason in the Petersburg, VA area in 1737, when the Governor selected him on behalf of The Crown to be the Governor’s Surveyor. The job included civil engineering, surveying, and masonry, but at that time was also a type of “tax collector” for the king.. since a surveyor would travel and know the land and property boundaries. A surveyor also had access to inside, or otherwise private information regarding land and property ownership, so he was key in issues involving land and property on behalf of The Crown.

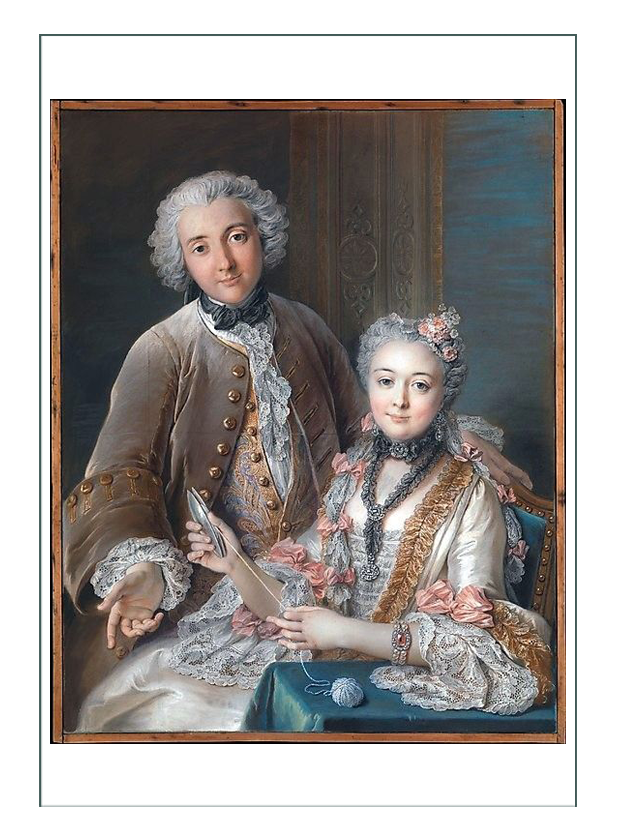

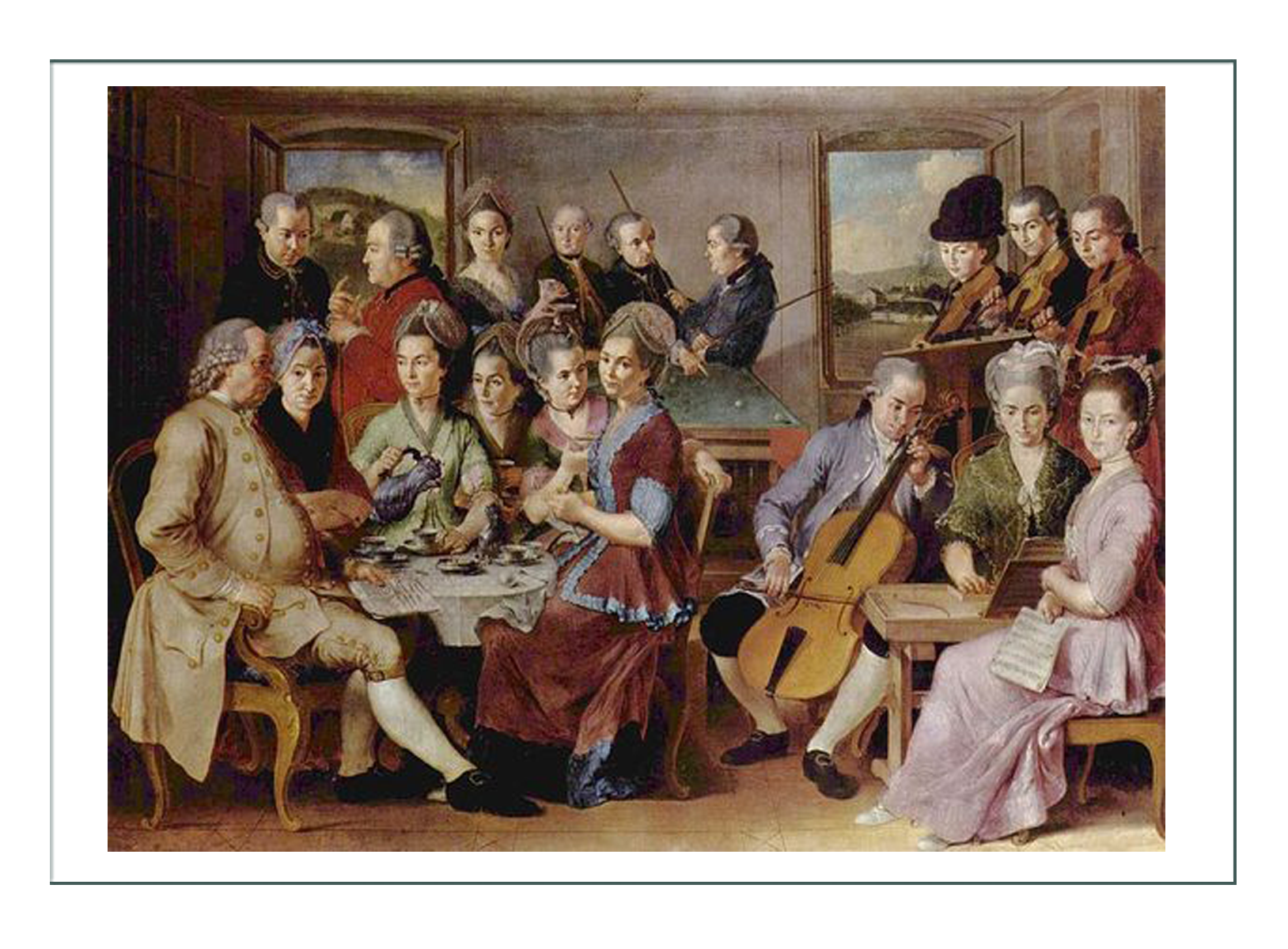

In 1740, as surveyor, Edward worked closely with Colonel Baker, as they both sat on the King’s Council. There he met Mary Baker; one would guess at government function such as a dance or tea (women would not have been allowed in meetings). Oral histories tell the following story about their marriage. This is written in the 1789 “William & Mary Quarterly” publication as well as passed down in handwriting by family members:

“Edward fell in love with the daughter, Mary, and she with he, and asked for her hand before the father and brother. Said parties refused his suit entirely and vehemently, because Pegram was ‘socially beneath them’.”

“But Pegram was physically and mentally strong with undaunted courage and was not disposed to yield to their whims. He took Mary to a private place where he asked her again , who agreed to marry in spite of her family” (she was 18 and he was 19) “… he advised the family he would come and take her from the house. On the day appointed, he appeared and took her from the house, mounted her on the horse behind him, and carried her to a parson and they were married.”

From his position as surveyor, Edward knew where the best land was, and arranged with an English civil engineer named Slaughter in Dinwiddie County, Virginia (just south of Petersburg) to find 10 miles square of farmland which he made into a plantation. History records on this land “he settled and prospered and soon became a wealthy and influential member of the county”.

There is no record of military service for Edward himself, although his son entered service in the Revolutionary War, and became a Captain in the Continental Army. One can only assume, with an English wife who had been abandoned by her family, and who was an intimate of The Crown, that loyalties were divided or neutral approaching and during the Revolutionary War.

At the time of the War, Edward and Mary were residing on their plantation, called “Bonneville”. The house was a late Georgian style with Flemish chimneys, with Regency furniture. The doors had 6 panels forming a cross, which verbal history says was because of the superstition that it kept witches away.

Tax records indicate Edward was still living at Bonneville in 1796, and had 40 slaves (and many cows according to his eventual distribution at his death). Interesting by note, all his property was taken by the government at his death, and his grandson bought it back. The family maintains that farm to this day.

The farmland wore out due to lack of crop rotation, fertilizer, and erosion control, and so many descendants moved to Tennessee and North Carolina to farm and to present date have plantations in those areas.

In March 1865, 2 battles near the end of the Civil War were fought on the Pegram Bonneville property. Locally known as “The Pegram Battle”, it was part of Sherman’s march which also destroyed the nearby town; “Battle of Chamberlayne’s Bed” aka “battle of Dinwiddie Courthouse”. Confederates were flanking a Major Sheridan attack against the Union calvary corps, and trapped Union soldiers upstairs in the house where they killed them. Generations later were pulling musket balls out of the walls of the Bonneville house.

Edward and Mary had a son in 1742, less than a year after their marriage. It is assumed they were still living in or near Williamsburg at that time. It was after Edward retired from service to The Crown (date unknown), that they moved to Bonneville.

Mary and Edward Pegram had 11 children:

- William: b. 1742, d. 1787

- Mary: b. 1744 died in infancy

- Edward: b. 1746 some have his birthdate as 1772 d. 1816. Was a juror in 1807 in the trial of Aaron Burr, who killed President Alexander Hamilton in a duel

- John: b. 1748 d. 1814 Became Major General John Pegram.. confusing in history in the Continental Army (indicating their Patriot leaning, but having maintained his surveyor commission, would assume Edward Sr. walked a fine line, while his children embraced the Patriot cause).

- Elizabeth: b. 1750 married, but no death record

- Sallie: b. 1753 married, but no death record

- George: b. 1755 married, but no death record

- Baker: b. 1758 d. 1830 was a Major in the Revolutionary War

- Daniel: b? died in infancy

- Ann: b. 1762 married, but no death record

- Danel: b. 1767 d. 1815

In 1777, the time of depiction, the young son Baker (her family namesake, so supposedly a special son to the mother) married Mary Manson, and they had a son in 1778. This child was named Edward after his grandfather, which has caused much confusion in oral histories of the family.

In 1778, Mary’s youngest child would have been 11 years, and her eldest 35.. quite a spread, and with many grandchildren, the house was probably full.

COLONIAL MEN & WOMEN – NOT ALWAYS THE ROMANTIC IDEAL

Mary would have had a firm English accent (Bristol region) mixed with a southern twang of Virginia, but one would guess she would have tried to hide her accent somewhat to embrace her new country, since she had given it all up to marry. It would seem despite her being banned from her own family, that having 11 children, the relationship was quite good between Mary and Edward their entire lives.

One bit of history mars the pretty picture of a perfect wife and family. Very little is “primary source” documented about any of the family beyond birth, death, and property ownership records, because of the records being burned in the Civil War. The few court documents which exist describe a man of the era who might not have been our romantic ideal.

In 1742, at the beginning of their marriage, a group of records show Edward “serving papers” on landowners and collecting “50 shillings”; presumeably as part of his job for The Crown.

In 1748, he was called to suit in the death of a runaway slave that was owned by John Jones (a neighbor who shows up in later discussions about political meetings as a friend). Edward beat the neighbor’s slave to death when he caught the slave on his property, and was ordered to pay Jones 40 pounds (English currency) and to “give prayers for relief” (apology).

This speaks of the era, the culture, and Edwards and Mary’s place in society as plantation owners who believed slaves were property. Her background in nobility would have her comfortable in this, as she came from a strict social hierarchy. One would guess they were “social snobs”, and worked to keep their status clear of lower classes.

One could also surmise they had “issues” with The Crown, and her family. Mary’s mother disinherited Mary and her family completely, but Mary’s father, Daniel Baker, and her brother reappear in 1780 after the death of Mary in a story about the emissary of John Wesley, the founder of the Methodist Church in England. The relationship with members of the churches picks up the story of the family.

POLITICAL AND RELIGIOUS CHARACTER & DEALINGS

From what we know about English/Scottish migration to the colonial US, many were escaping prosecution because they were protestants. The year 1740, when Mary came from England, was just before the 2nd Protestant Uprising in Scotland and England, when conflict and trouble was just gaining a foothold with the English King (with George, and then with Charles).

Part of this migration due to persecution in Europe were the Methodists. Unfortunately, when they came to an English held colony that was not yet the United States (pre-revolutionary), they were still persecuted. Methodists were considered Anglicans which the King hated. The governor and other officers of The Crown, including Mary’s father Colonel Baker, were required to commiserate with the King, and exile Methodists and all considered Anglicans in the new colonies the same as in Europe.

John Wesley (founder of the Methodist church) sent Francis Asbury as am emissary to evaluate and work to improve the situation for “our brethren in America”. Edward & Mary’s father and brother, against the wishes of the English king, it would appear united in the cause to help the Methodists.

Private records show Edward & Colonel Baker held a private meeting in Edward’s Bonneville house in 1780 for elite society, and hosted another public meeting with 400 attendees in Bushnells’ Chapel in Petersburg, VA. As this would be nearing the end of the Revolutionary War which officially ended in 1783, one could assume at least the father’s side of Mary’s formerly English family had completely embraced the new United States of America, and supported the Patriots against the Crown.

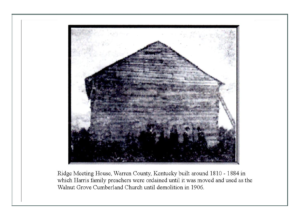

Interesting side note: To this day, most Pegrams are Methodists, although many, especially those who moved to Kentucky and Tennessee.. and later further west into Illinois and Missouri, became extremely conservative Presbyterians or Episcopalians. There is an extended side of the family 3 and 4 generations past Edward and Mary, where the Pegram/Baker progeny join (author’s) Harris/McClure English/Scottish relatives (who also arrived in about 1740 to the Colonies) in leading the split between the Presbyterian Church in the Bowling Green, KY region. These combined families continued the very strict, Anglican practice, while most of the new Americans were become less structured and disciplined in their religion.

LATER LIFE

At the death of Mary’s father Daniel, her mother married a wealthy man from New York City named Patrick Oglesby. The daughter of this second marriage, Mary’s half sister, married and returned to live next door to Edward and Mary’s Bonneville property. From this point, the two families, the Baker/Oglesbys and the Pegrams, returned to intermarry and continue a (confusing for geneologists) line which crossed back and forth in land ownership in Dinwiddie County, Virginia.

At present most documents regarding this family are tied to the Dinwiddie County Pegram descendants, and are tied to the West Virginia or Virginia Regiments of the Revolutionary War where the children and eventual cousins of Mary and Edward’s cousins would have fought together.

The significance of the “Scott” part of Mary’s name, and as she named several of her children is not known. It was rare that a mother could get a surname such as that used legally, so she must have had some “clout” somewhere. There was a predominant family of the James Scott heritage living in Dinwiddie County, but they were not related.

Mary died in 1779, some records say 1780 at age 53, so it was not in childbirth. There is no record as to the cause of her birth.

Click to go to Carol’s Historical Research Time & Place Page (next)

Click to go to Carol’s Historical Research on Character & Fashion Page

Click to go to Carol’s Design Development Page

Continue below to see the FINAL PRODUCT

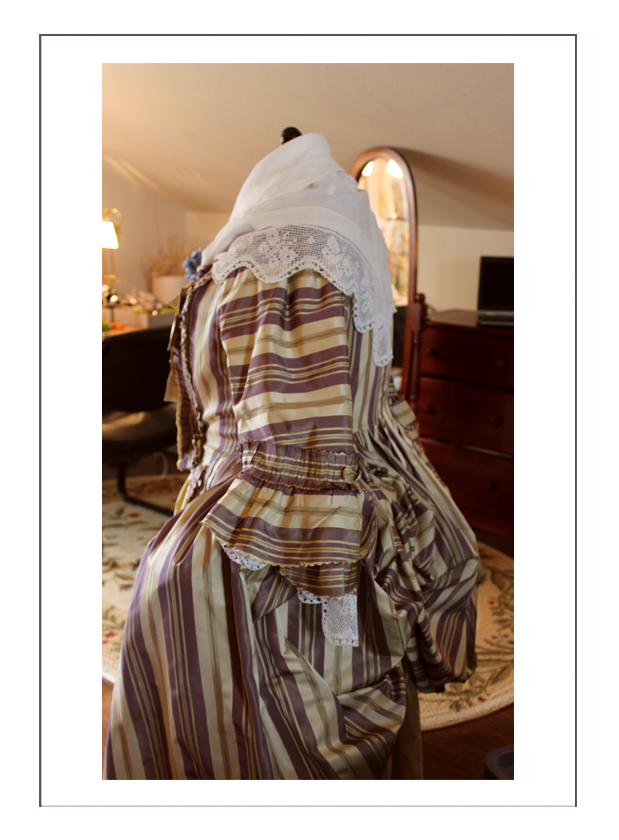

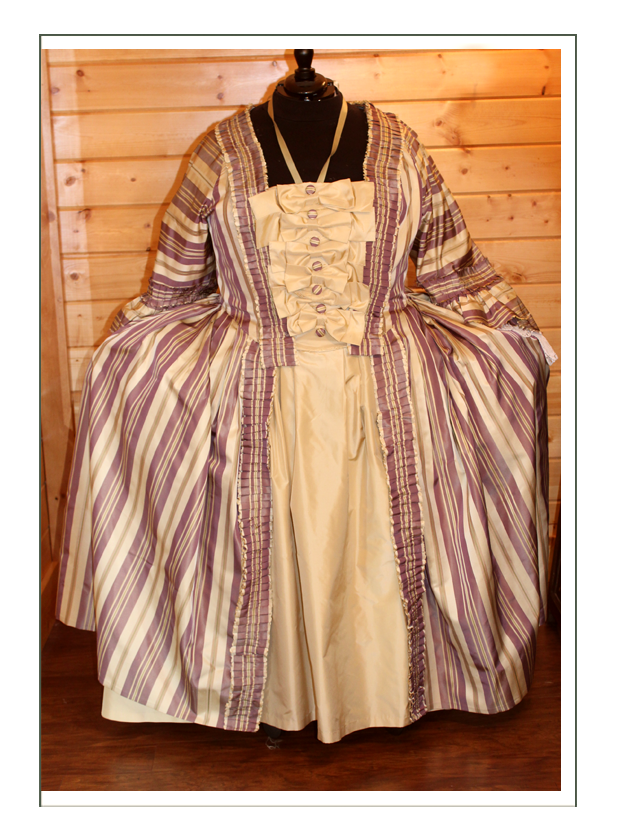

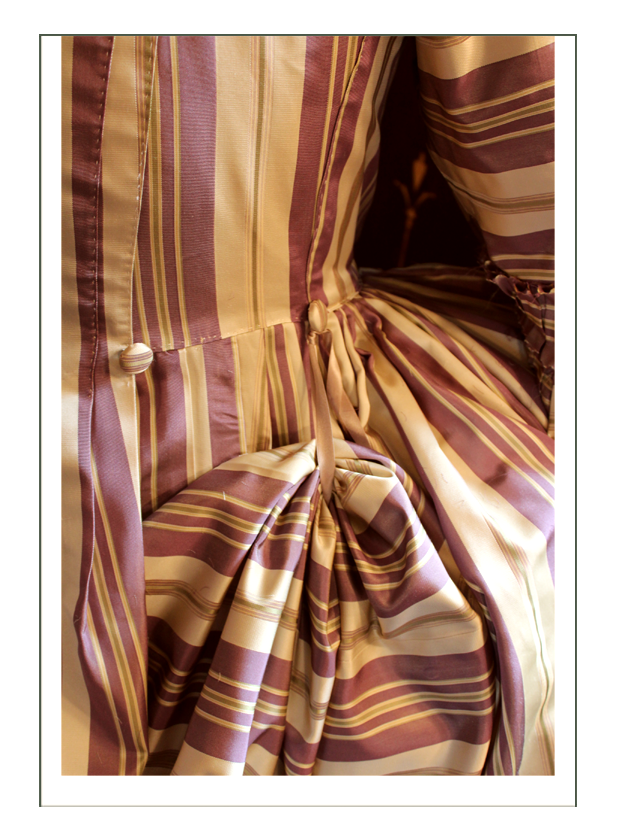

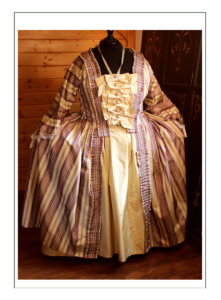

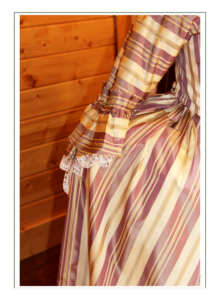

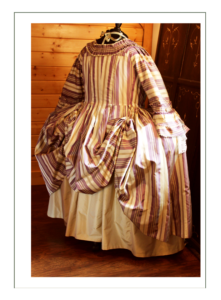

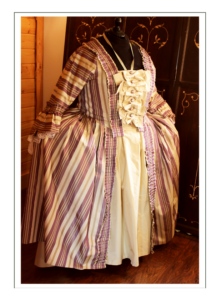

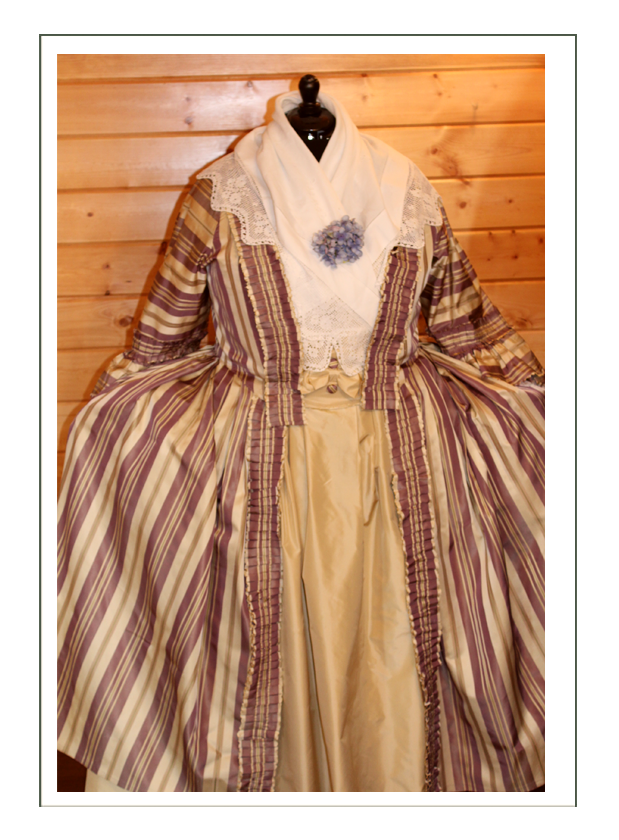

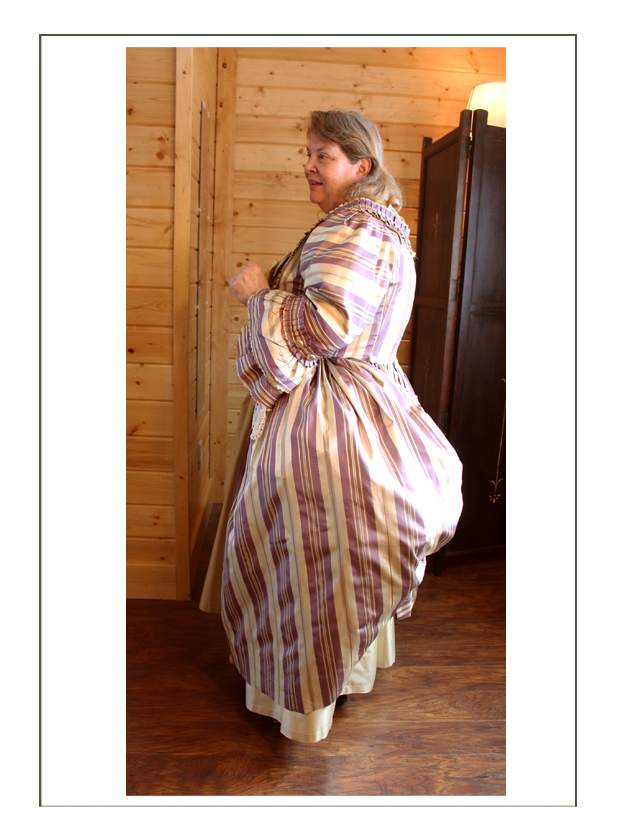

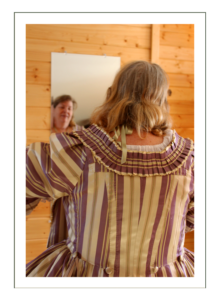

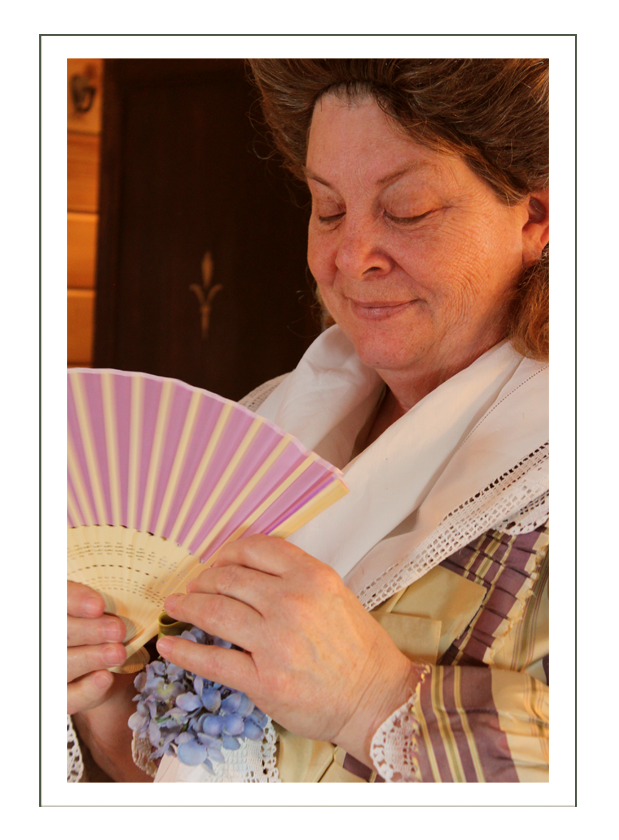

Silk Tea Ensemble 1765-1775

FINAL FABRIC SELECTIONS

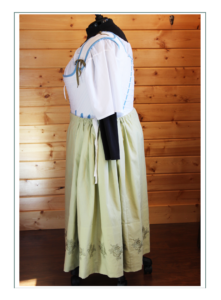

Completed Garments

Chemise

Chemise modified

Inner Petticoat

Inner Petticoat Modified

Inner Petticoat Modified

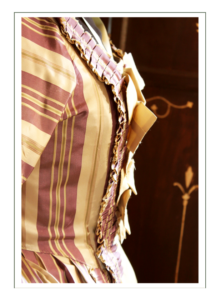

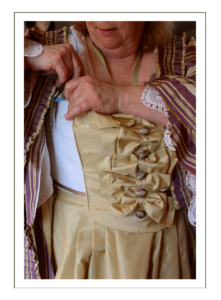

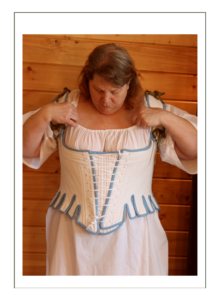

Stays

Stays Modified

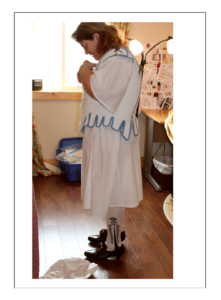

Paniers

Paniers Modified

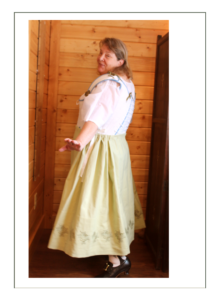

Outer Petticoat

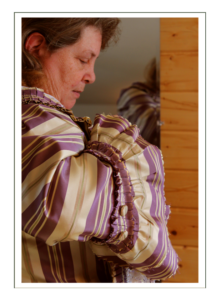

Robe de l’anglaise en forreau a la polonnaise

Fichu & Flower

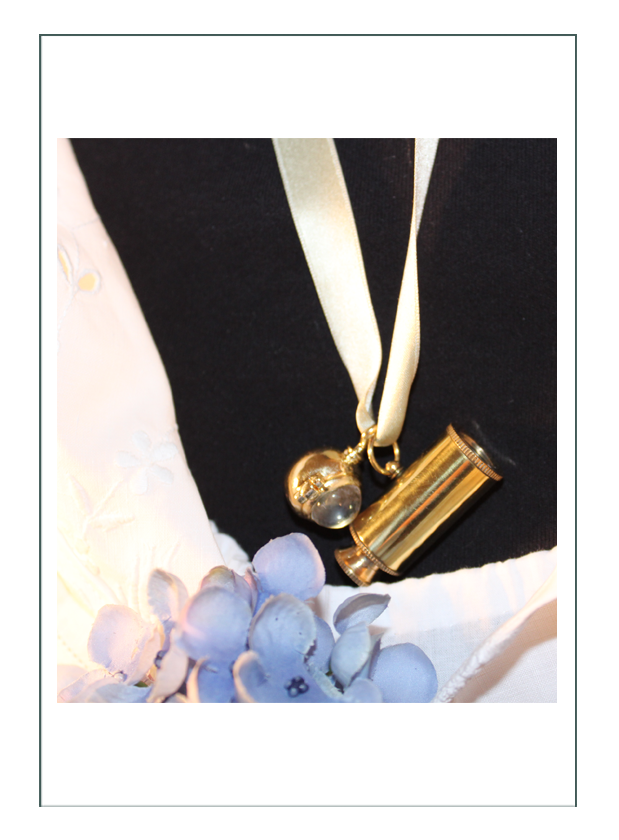

Necklace

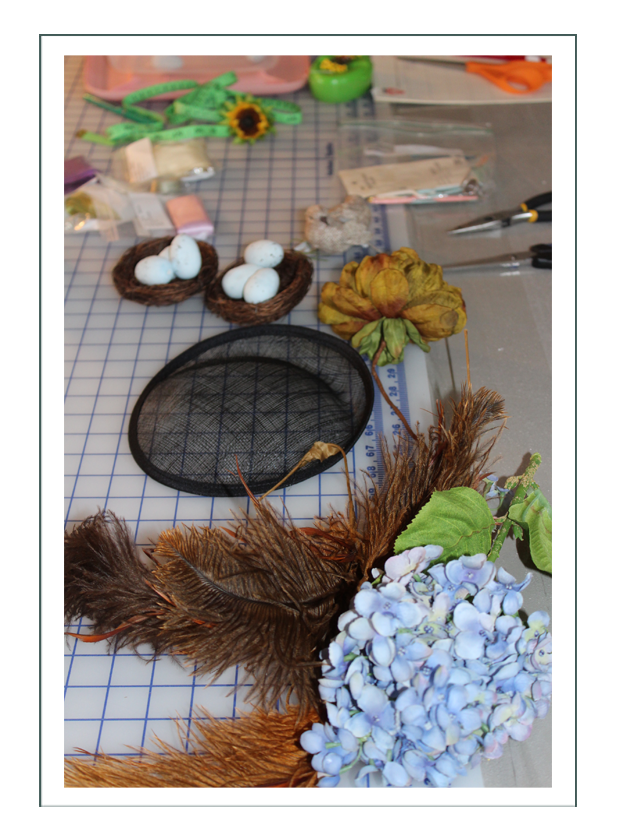

Head and Toe

![]()

Click to go to Carol’s History of Fashion of the time Page

Click to go to Carol’s Design Development Page